Head Over Heels (1987)

Some eighteen months ago now, I took my reluctant wife with me to see Star Wars: The Force Awakens. As we left the theater afterward, she seemed unimpressed by all the action and drama she’d just witnessed. Instead she focused in on the comic relief, which largely takes the form of lots of charming little cartoon-ready robots. She passed along one of those insights that remind me why I married her. “You know,” she said, “nerds are always trying to be cool with their science fiction and their big guns and their explosions and all that other dark stuff, but what they really love most of all is cute stuff.”

In nerdom’s eternal tug-of-war between the cool and the cute, the former tended to get the best of it for many years in the realm of videogames. Yet there were exceptions, and one of the more notable of them from the British gaming scene of the 1980s was a lovable action-adventure called Head Over Heels— because sometimes you’ve just got to let your cute flag fly.

Head Over Heels was the creation of an easygoing 30-year-old named Jon Ritman, who had been working for a consumer-electronics rental outfit as a television repairman when he started hearing about these strange new gadgets from companies like Sinclair which his customers were beginning to connect to their idiot boxes. He bought his first Sinclair ZX81 in 1982, took to it immediately, and saw his first game published within six months. But he really hit the big time when the management of Ocean Software convinced him in 1984 to write a soccer game for the Spectrum. Despite having no personal interest in the sport, Ritman managed to make a game that felt more like real soccer than anything that had appeared on a computer to date. Indeed, many will tell you even today that Match Day was never bettered on the Speccy — unless it was by Ritman’s own 1987 sequel. The two games sold well into the six figures in footy-mad Britain, making Ritman one of the coder stars of the Speccy scene.

We’re much more interested today, however, in what Ritman did between Match Day and Match Day II. Inspired like so many others by Ultimate Play the Game’s Knight Lore — this really is becoming a broken record, isn’t it? — he decided he wanted to make an isometric action-adventure. Looking for a hook that would make his game stand out from the pack of Knight Lore clones, he convinced Ocean to acquire the license for Batman — not so difficult or expensive a proposition as you might expect in those days before the first big Batman movie. Working with an artist named Bernie Drummond, in 1986 he finished designing and programming a game around the character, which Ocean released to very strong reviews. And then, with the follow-up, Ritman and Drummond truly struck gold.

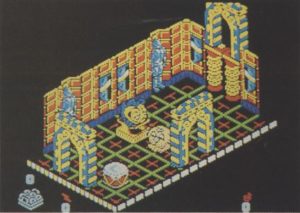

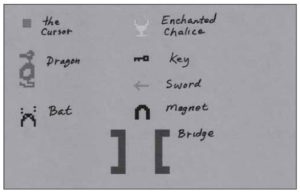

Head Over Heels is yet another Knight Lore-inspired isometric action-adventure, but it has one big twist that makes all the difference: you control not one avatar but two, switching between them as you will. Both are vaguely dog-like creatures, and both are very, very cute. In the beginning they were known as “Foot” and “Mouth,” thus lending the game the unappetizing title of Foot and Mouth, but Ritman or his publisher thankfully came to the realization that naming his game after a rather grotesque bovine plague might not be a great marketing idea. So, the two doggies became “Head” and “Heels.” Head has hands and wing-like appendages that let him leap long distances, but no legs, making movement on the ground a slow and laborious process. Heels has legs that let him move quickly and easily over the ground, but he’s not very good at jumping and doesn’t have any hands at all. Head is dexterous, good at manipulating his surroundings, but isn’t very strong and can’t carry very much. Heels is strong and tough, and can carry a lot of weight, but, lacking hands, can’t do much in the way of delicate object manipulation.

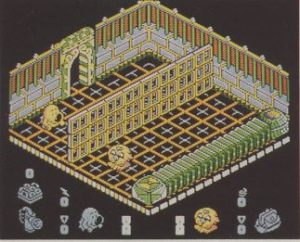

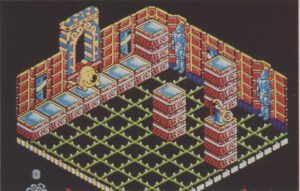

Head and Heels can see one another as the game begins, but are separated by the bars of their cells. The game will continue to torment you like this throughout its early stages, as the two keep coming so close yet remaining so far. When you finally do manage to bring them together, it’s a big moment — but the game proper has barely begun. (This screenshot and those that follow is from the later Amiga version of the game, in which it’s a little easier to make out details.)

Head and Heels normally go about together, but at the beginning of the game they’ve been imprisoned in separate cells by minions of the evil Blacktooth Empire. Your first big goal is to effect their reunion, a challenging and fairly lengthy process in itself. Once you do finally manage to get them together in the same space, they reunite in an even more literal sense: Head can ride around on top of Heels. From here on, solving the game’s puzzles will be a matter of applying the talents of one or the other doggie correctly, or of setting them to work as a team to solve the really gnarly problems, as you explore five worlds totaling some 300 rooms. Your goal is to collect the five lost crowns which can bring freedom to the doggies’ homeworld — which is called, appropriately enough, Freedom.

As I’ve had occasion to say over and over in the course of this series, just the fact of these worlds’ existence inside the memory of a 48 K Sinclair Spectrum is amazing in itself. Ritman himself estimated that each room uses an average of just 17 bytes, with the entire slate of 300 rooms filling all of 5 K. Otherwise, the game uses 2 K for its sound effects, about 17 K for its graphics data, and about 20 K for its actual code. Yes, I’ve said it before about other games in the course of this series, but that doesn’t make it any less important to acknowledge what a wonder of compression Head Over Heels is.

Still, that’s not what makes it stand out from a field that’s so full of such wonders. In terms of pure design, Head Over Heels may be the best single game I describe in this series. Perhaps because he was a little older than most of the other programmers in question, perhaps because he was a little more sociable, Ritman showed a willingness to play-test and iterate over his concepts that most of his peers — meaning by no means only the peers mentioned in these articles — tended to lack. “You have to envisage how the game is going to play,” he said. “I do think you have to get the game play right in order to make sure you’ve got something worth playing. Some programmers spend so much time trying to produce a work of technical genius that they lose sight of the game play.” In Head Over Heels, this focus on the player resulted in a game that’s challenging, but never overwhelmingly so in the way of some other suspects from this series.

One great example of Head Over Heels‘s relatively forgiving nature is its use of save points. As you explore its worlds, you’ll sometimes come upon “resurrection fish.” Eating one of these acts as a save. From then on, if Head or Heels runs out of lives you’ll be returned to the point where you last ate a resurrection fish rather than punted all the way back to the beginning of the game. A worthy compromise between the tension-draining mechanic of allowing universal saving at any point and the heartless one of kicking you all the way back to the beginning of the game every time you lose your last life, save points are found everywhere in the games of today. But Ritman, beginning actually with Head Over Heels‘s predecessor Batman, was among the very first to employ them. Their existence in his games at this early date only serves to hammer home what a progressive designer he was in contrast to his peers.

If Head can get over to that thing that looks like an air horn, it would be a good thing: it’s actually a doughnut gun. Doing so will, however, require some precision jumping.

One could say much the same about Head Over Heels‘s unabashed cuteness as well. Both Head and Heels are adorable to watch bounce and frolic about the rooms. Humor and whimsy are everywhere in this game. If the doggies alone aren’t cute enough for you, there are fluffy little “bonus bunnies” running around, along with a robot version of Prince Charles among various other hilarious non sequiturs. Early on, Head will be able to acquire a gun that fires… doughnuts. Why doughnuts? Why not? Throughout its considerable length, Head Over Heels never fails to surprise, to charm, and to delight.

Greeted with superlative reviews in its day, Jon Ritman’s second and last isometric action-adventure for the Sinclair Spectrum nevertheless failed to sell as well as the licensed Batman had. Still, its reputation only grew in the years thereafter. By 1991, when Ocean released new versions for the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST, it had become an acknowledged classic. “It’s cute, puzzling, frustrating, and absorbing in equal measure,” wrote reviewer Ciarán Brennan in the magazine The One. “The beauty is that the game play is completely timeless. If you’ve never played the game before, you’ll find a fresh teaser around just about every corner, while those of you who played the original for years will probably have forgotten the solution.” He went on to call it “one of the few genuine masterpieces of computer gaming.” Heady praise indeed, but on the whole it’s warranted. The status of Head Over Heels has only continued to rise since Brennan wrote those words. Today it’s usually one of the first games cited whenever the subject turns to the greatest, most timeless of all Speccy classics.

After publishing Match Day II later in 1987, Ritman left the Spectrum scene in favor of programming console and handheld games, working for a time with his old idols, the people who had once been known as Ultimate Play the Game but now went by the name of Rare. He’s continued to bounce around the industry to this day, although, with his days as one of British gaming’s greatest open-world auteurs now well behind him, he keeps a much lower profile than he used to.

Thankfully, those who wish to play what is arguably his most singular achievement from those glory days have great options for doing so today. There are in fact two worthy remakes for modern computers on offer, one from a group of Speccy old-timers who call themselves Retrospec and the other from a Spanish fan named Jorge Rodríguez Santos. Both look and play superbly, capturing everything that made the original a classic — but doing so in blessedly higher resolution. While it’s a shame that the other games I write about in this series couldn’t enjoy such dedicated patrons as Retrospec and Santos, it’s hard to shake the belief that, if only one of them was to be given such loving treatment, it ought to have been this one.

Exile (1988)

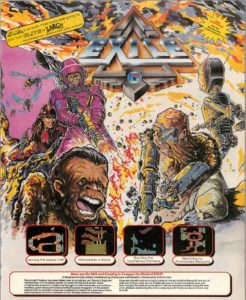

Coming nine years after Warren Robinett created his Adventure on the Atari VCS, Exile, which embraced much the same design philosophy but blew it all up to well-nigh absurdist proportions, feels like the logical end point of what he began. It’s hard to imagine a bigger, more fascinating, more daunting action-adventure than this one. And really, it’s hard to imagine why anyone would even want such a thing. Exile is packed full of so many creatures and puzzles and hidden nooks and crannies that its secrets have yet to be exhaustively cataloged, in spite of the best efforts of a small but devoted cult of fandom who have been at the job for a few decades now. Its warren of underground caverns just go on and on and on, with something new to discover behind its every twist and turn. How remarkable that the game’s programmers, Peter Irvin and Jeremy Smith, created this monster inside the most constrained platform of any of the games we’ve looked at since Robinett’s Adventure: a 32 K BBC Micro.

Much more expensive than the populist favorite Sinclair Spectrum, the BBC Micro had a reputation as the platform of choice of the eggheads and the posh. Irvin and Smith fit that reputation to a tee, coming out of two of their country’s most prestigious universities: Cambridge in the case of the former, Imperial College in that of the latter. Each had published a game on his own before they came together to work on Exile. Smith’s game, a space shooter called Thrust that was notable for its painstaking physics model, had the most obvious influence on the new project. Smith had, as Thrust‘s advertising didn’t hesitate to trumpet, a “First-Class Honours degree in Physics!” That education, along with the experience gained in making Thrust, fed directly into Exile.

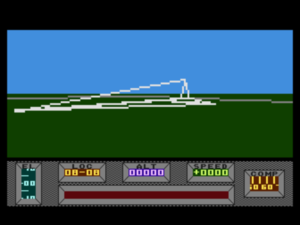

Already by the late 1980s, videogames had a surprisingly long history of doing justice to the vagaries of spaceborne physics. A quarter-century before, Spacewar!, widely acknowledged as the first true videogame ever, had been fought out by two spaceships inside the gravity well of a star, with all the danger and potential for fancy maneuvering that implied. Many of the earliest standup-arcade hits took Spacewar!‘s example to heart, from the oddly cerebral, non-violent exercise in thrust and fuel management that was Lunar Lander to the more straightforward blow-the-aliens-out-of-the-sky action of Asteroids. In Britain, one of Ultimate Play the Game’s reputation-establishing hits had been 1983’s Jetpac, another game of, among other things, thrust and inertia.

Exile doesn’t use the isometric view Ultimate pioneered the year after Jetpac, nor the immersive three-dimensional visuals of Mercenary. You view its flat two-dimensional landscapes from the side. Indeed, despite coming five years after Jetpac, Exile at first glance doesn’t look all that dissimilar to it: its hero as well is a little jet-pack-wearing fellow squirting about the screen. But looks can be deceiving: not only is Exile‘s physics model superior even to the one from Thrust — much less the simple arcade physics of Jetpac — but, even more importantly, Irvin and Smith made a huge living world for their little hero to fly about in.

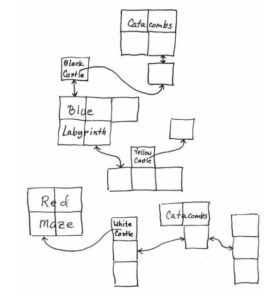

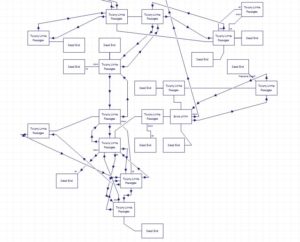

Just how big is Exile, you ask? In early 1991, more than two years after the game’s initial release, Acorn User magazine published the first complete walkthrough, accompanied by the map you see above. The walkthrough proper came in three parts published in three successive issues, despite being printed for the most part in a coded shorthand. On the map above, each of those little numbers you can just barely make out corresponds to the location of some task you need to do in the walkthrough. So, yes… Exile is very, very big.

The plot is some generic sci-fi business that sends you to the planet of Phoebus to rescue a group of hostages from some evil overlord or other; it’s hardly necessary to dwell on it here. What really mattered to Irvin and Smith were the emergent qualities of the living world they were building. Like Elite, Exile generates its world procedurally rather than attempting to store a hard-coded geography in memory; the latter would be a hopeless approach to making a world this big on a machine with a memory this small. Its creators tweaked the numbers inside the equations that brought their world into existence again and again until they found a layout they liked.

Then, they filled their world with creatures and things. Echoing Warren Robinett’s approach in his Adventure, all of the creatures in the game have “fears and desires” guiding their actions. Irvin and Smith avoided single-solution puzzles like the plague. Everything that happens in Exile is emergent behavior; it’s a more pure simulation than most simulation games. “You weren’t meant to feel railroaded through a route,” says Irvin. “It was ‘there you are, there’s your planet to explore.'” Thanks to the procedural generation, even the world’s creators had nothing like a full mental picture of what all it contained, what all possibilities it presented.

Incredibly, all of the graphics that are mixed and matched to portray the world of Phoebus on the BBC Micro fit onto a single screen.

Of course, all of this inevitably turned into a double-edged sword. The problem with a world that even its creators don’t fully understand, a world where anything can happen, is that too often things happen that aren’t much fun, or that wind up breaking the game for its player. In the massive, chaotic virtual space that is the world of Phoebus, it’s all too easy to lose your bearings and with them all sense of what you’re trying to accomplish. Taking the form of an action-adventure, a genre that was billed as a more immediate, visceral alternative to the cerebral text adventure, Exile paradoxically demands oceans of patience of its player; most players won’t find their first weapon until a couple of hours into the game. And it must be one of the most overwhelming games ever made. A surprising number of even its most hardcore fans have never come close to finishing it. Playing through Exile in its entirety straight from a walkthrough is far more time-consuming and difficult than playing the vast majority of games honestly. But then, perhaps focusing too much on beating Exile is rather missing the point. For the vast majority of its fans, the real source of the game’s appeal isn’t in the challenge of completing it but rather the fun to be had just poking around in its world, seeing what you can make happen, seeing what hidden delights you can discover. [1]It’s likely that the majority of people who have played Exile have done so on versions that were literally impossible to complete. One other aspect of the game’s legend is its copy protection, which stands as the most devious of its era. Instead of simply booting you out of the game, the layers upon layers of protection, personally devised by Irvin and Smith, subtly alter the game to make it impossible to complete. Exile‘s copy protection stands as one of the vanishingly few examples of same that fully, comprehensively did its job, defeating absolutely everyone who ever tried to crack it until long after the game was no longer being sold. On some platforms, cracking Exile took decades; on others, that feat has apparently never been fully accomplished. The copy protection thus stands as one more part of the game’s legacy of shattering every technical precedent — a pursuit that Irvin and Smith engaged in with monomaniacal intensity.

Exile‘s launch in the fall of 1988 turned into a somewhat more muted affair than Irvin and Smith might have hoped for. Superior Software, the small publisher behind the game, did their best to evoke the heritage of that earlier BBC Micro landmark Elite, and with it that of David Braben and Ian Bell, the legendary earlier pair of BBC Micro programmers who had also used procedural generation to make the machine’s 32 K seem more like 32 M. Superior packaged Exile with a 20,000-word novella similar to the one that had shipped with Elite, and even convinced Braben to offer up a blurb of praise. Yet, whatever else you could say about it, Exile wasn’t a game with quite the same immediate appeal as Elite. Reviewers for the most part praised its accomplishments — how could they do anything else with a game of this ambition and technical achievement? — but sometimes seemed to do so more out of a sense of duty than passion.

After Exile was revamped by Irvin and Smith for the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga in 1991, it was greeted still more skeptically by some reviewers. Trenton Webb, reviewing the Amiga version for the magazine Amiga Format, provided an unusually cogent summary of the game’s mixture of strengths and weaknesses:

Exile is no classic, despite its glorious control system. The game doesn’t develop quickly enough to grab players by their interest and drag them in. The first layer of traps are deadly enough to frustrate, but vary little from the “fetch Object A to use on Object B thus freeing Object C” variety. It is also too easy to find yourself stranded after a single slip-up. RAM-save and disk-save facilities are provided to help alleviate this problem, but this cures the symptom and not the ailment.

The lack of dynamism makes this a game for the connoisseur who fancies something different. Exile is different, brilliant in parts, poor in others. It defies categorisation. If this system could be married to a more riveting concept, we would be talking major title. Without this pulling power, it’s relegated to the role of delightful curiosity.

The status of delightful curiosity, though, isn’t such a terrible one to wind up with in the annals of gaming history. To this day, Exile stands out for its absolutely uncompromising commitment to its emergent living world. Sure, most players — among them your humble writer here — will eventually shrug their shoulders and go off in search of a tighter, more designed world to play in. As its persistent cult of hardcore fans attests, however, for some the world of Phoebus gives rise to an unquenchable compulsion to sound its depths. Despite existing inside orders of magnitude upon orders of magnitude more memory, few modern living worlds feel quite so alive as this one. While Head Over Heels is in my opinion the strongest of the game designs I’ve written about in this series, Exile is the most awe-inspiring technical achievement of the entire awe-inspiring bunch. It ought to be recognized, perhaps even more so than the storied Elite, as the ultimate example of British programmers’ genius for doing more with less.

Jeremy Smith died in an accident in 1992. Peter Irvin stayed in the industry for some years, spending most of that time working with David Braben’s company Frontier Developments, where he helped to make the long-awaited sequel to Elite, Frontier: Elite II. He moved on to other pursuits in the latter 1990s.

There have been various projects that proposed to revive Exile for modern platforms, but none have reached a playable fruition. Your best bet for experiencing it today is therefore an Amiga version which has been authorized by Peter Irvin and verified to be completable.

Dizzy (1987-1992)

Coming at the end of such a string of enormous and enormously ambitious games, the Dizzy games might at first glance seem to make a piddling way to conclude this series of articles. Certainly no one would accuse these games of innovating overmuch, and their worlds don’t challenge anything I’ve written about earlier in terms of size, detail, or technical excellence. In a way, though, that’s what makes them such a perfect concluding statement on this topic. Apart from the outliers we’ve already witnessed, the games that pushed all the boundaries of what was reasonable to attempt on an 8-bit computer, British computing of the 1980s was filled with more modestly conceived worlds of action and adventure. Before we move on, then, let’s take a moment and pay our respects to their more everyday sort of amazingness through the story of a good egg named Dizzy.

The Dizzy games were the brainchild of a pair of identical twins named Andrew and Philip Oliver who were more noted for their prolificacy than their design ambition. After finishing their studies at Wiltshire Comprehensive School in 1986, the 18-year-olds decided to become independent game programmers, relying on a grant of £40 per week from the government’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme to get them started. They were fortunate in that another pair of brothers, Richard and David Darling, were starting a company of their own at the very same instant: Code Masters, a new budget publisher. The Oliver twins signed on with them, and soon turned into a veritable game-making machine. Over the course of the late 1980s, they alone would account for more than 50 percent of Code Master’s constant stream of new games. Initially, most of the Olivers’ games took the form of a series of “simulators” like Grand Prix Simulator, Professional Ski Simulator, or the boring but bizarrely popular Fruit Machine Simulator.

The twins made it their policy never to spend more than a few weeks on a game. Selling at the rock-bottom price point of £1.99, their games were essentially disposable products, intended to provide a weekend’s entertainment, after which the buyer would presumably head back down to the shop to buy another one for the next weekend. Asked whether he might ever prefer to make something bigger and more carefully crafted, Philip Oliver made it clear where his priorities lay: “The more games we release, the more we sell. If people buy one and like it, they’ll want to buy more games we write.” While none of their quick-and-cheap games were masterpieces, the Oliver twins did have a knack for making something that was playable and reasonably entertaining, at least in the short term, on an absurdly tight schedule. Their games mostly managed to be just good enough that their customers could indeed feel they had gotten their money’s worth, and would thus be willing to buy another.

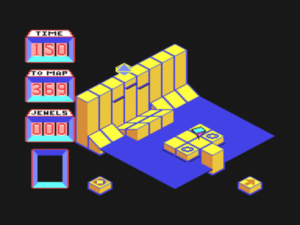

The character of Dizzy was born when the Oliver twins decided it was time to aim their game-making machinery at the action-adventure market. They made their new hero a big egg with a face painted on because that seemed the best way to give him a distinctive look, given the low-resolution graphics of the machines they worked with and their own less-than-stunning artistic skills. He made his debut, selling at Code Master’s standard budget price, on the Amstrad CPC, the twins’ programming platform of choice, in Dizzy: The Ultimate Cartoon Adventure in September of 1987. When the game proved a strong seller over an unusually long period of time, the twins just kept going back to the well in typical Oliver fashion, cranking out another six Dizzy action-adventures, plus five more straight-up action games starring the character, over the next five years.[2]An eighth action-adventure, 1991’s The Fantastic Adventures of Dizzy, didn’t make it to the likes of the Amstrad and the Speccy. Coming chronologically after the sixth action-adventure in the series, it was released on the Amiga and MS-DOS as well as the Sega Genesis and Nintendo Entertainment System. This last version was an unauthorized game, released without Nintendo’s consent, employing a system Code Masters had developed for defeating the NES’s lockout mechanism. The war between Code Masters and Nintendo that erupted as a result of the former’s unauthorized games as well as their Game Genie, an unauthorized hardware add-on that made it possible to “cheat” at many NES games, was just as bitter as the one that raged concurrently between the two Ataris and Nintendo.

Frozen out at retail by the same tactics Nintendo wielded against Atari’s Tengen games, Dizzy didn’t have a very successful go of it on the NES. His one attempt at branching out having proved disappointing, he returned to his traditional platforms for his last outing, 1992’s Crystal Kingdom Dizzy.

From their easy-to-program two-dimensional graphics to their mixture of light platforming action with simple puzzles, the Dizzy series didn’t change very much from game to game — or, for that matter, from the very first game in the series to the very last. Each stuck the cute little fellow in some new setting and set him to it, jumping and puzzling his way through its screens from left to right. What some players decried as a pathetic lack of ambition others actually came to appreciate; the Dizzy games turned into a sort of comfort food for many. In a milieu that was normally so obsessed with novelty, a new Dizzy game was an old reliable that would never let you down. If it would be no better than it ought to be, neither would it be any worse. Although the Dizzy games were ported to many platforms, it was Amstrad owners who really took the little fellow to heart. He became their unofficial mascot, the nearest thing any of the British gaming platforms of the period had to a Mario or a Sonic.

In contrast to most of the action-adventures I’ve written about, which have tended to be purer graphical creations, the Dizzy games aren’t reluctant to use text to describe their often text-adventure-like puzzles.

But Dizzy wasn’t as successful as those peers at making the transition from 8 to 16 bits. While most of the Dizzy games were duly ported to the likes of the Amiga, they weren’t greeted with a great deal of enthusiasm there. Writing about Crystal Kingdom Dizzy, the seventh and last action-adventure in the series, Tony Dillon questioned in the magazine CU Amiga why the Oliver twins kept “churning them out, even though this style of game went out with the Spectrum.” It was a harsh assessment, but an accurate one: the era of Dizzy’s popularity died alongside that of the Amstrad CPC, Sinclair Spectrum, and Commodore 64. Today he survives only as a memory of a certain time and place in gaming history.

The Oliver twins, for their part, have long outlived Dizzy in the games industry. Having begun the transition from being lone-wolf programmers to being executives even while the little fellow was still going strong, they ran Blitz Game Studios for many years after he passed into history, until financial problems forced them to shut its doors in 2013. They remain active in the industry today — as does their erstwhile publisher Codemasters, albeit now with a one-word instead of a two-word name, and now as a publisher of full-price games instead of budget titles.

The Dizzy games don’t represent the absolute best of British action-adventures under any terms you care to name. Yet I did want to write about them here as a stand-in for all of the other also-rans in the field. Just as the great text-adventure houses — Infocom foremost among them — pulled along a whole fleet of more modest practitioners in their wake, the trailblazers and envelope pushers we’ve seen over the course of this trio of articles spawned countless games like the Dizzy titles. By no means are all of them bad games; what they lack in innovation, they often make up for in craftsmanship. Indeed, in terms of accessibility and playability the Dizzy games do much better than many of the action-adventures we’ve looked at previously. For instance, the fact that you mostly start on the left side of their worlds and work your way to the right might give the feeling of a much more constrained, linear experience, but it also all but eliminates the ever-present problem of internalizing the vast geographies of the more free-form games of this ilk.

If you’re looking for a place to start with the Dizzy series — and possibly to end with it as well — you could do worse than the third game, 1989’s Fantasy World Dizzy. One of the popular favorites of the series, it was the last Dizzy of the 1980s and the last one which the Oliver twins programmed themselves, thus making it an era ender in more ways than one. In that same spirit, it seems to me a very appropriate way to wrap up this little journey through this remarkable corner of gaming’s past. You can download Fantasy World Dizzy and all of the other Dizzy games for use in your emulator of choice — or even play them all online — at The Dizzy Fansite.

(Sources: the book Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene; Computer and Video Games of June 1986 and October 1987; Crash of May 1986, October 1986, February 1987, April 1987, January 1988, April 1988, and the “supplement” of October 1988; Home Computing Weekly of December 13 1983; Sinclair User of May 1987 and June 1987; The One of September 1991; ZX Computing of June 1987; Acorn User of March 1988, May 1988, September 1988, November 1988, January 1991, February 1991, and March 1991; ACE of April 1991; New Computer Express of June 8 1991; Zero of April 1991; Retro Gamer 30; Amiga Format of June 1991; Zzap! of July 1991; Amstrad Action of September 1988, March 1989, December 1989, and December 1992; Computer Gamer of April 1987; CU Amiga of March 1993; ZX Format of Christmas 2003. Online sources include Jorge Rodríguez Santos’s brief biography of Jon Ritman, elpixelblogdepedja.com‘s interview with Jon Ritman, Gamasutra‘s interview with Jon Ritman, “Returning from Exile“ from The Escapist, and Andrew Weston’s Exile page.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | It’s likely that the majority of people who have played Exile have done so on versions that were literally impossible to complete. One other aspect of the game’s legend is its copy protection, which stands as the most devious of its era. Instead of simply booting you out of the game, the layers upon layers of protection, personally devised by Irvin and Smith, subtly alter the game to make it impossible to complete. Exile‘s copy protection stands as one of the vanishingly few examples of same that fully, comprehensively did its job, defeating absolutely everyone who ever tried to crack it until long after the game was no longer being sold. On some platforms, cracking Exile took decades; on others, that feat has apparently never been fully accomplished. The copy protection thus stands as one more part of the game’s legacy of shattering every technical precedent — a pursuit that Irvin and Smith engaged in with monomaniacal intensity. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | An eighth action-adventure, 1991’s The Fantastic Adventures of Dizzy, didn’t make it to the likes of the Amstrad and the Speccy. Coming chronologically after the sixth action-adventure in the series, it was released on the Amiga and MS-DOS as well as the Sega Genesis and Nintendo Entertainment System. This last version was an unauthorized game, released without Nintendo’s consent, employing a system Code Masters had developed for defeating the NES’s lockout mechanism. The war between Code Masters and Nintendo that erupted as a result of the former’s unauthorized games as well as their Game Genie, an unauthorized hardware add-on that made it possible to “cheat” at many NES games, was just as bitter as the one that raged concurrently between the two Ataris and Nintendo.

Frozen out at retail by the same tactics Nintendo wielded against Atari’s Tengen games, Dizzy didn’t have a very successful go of it on the NES. His one attempt at branching out having proved disappointing, he returned to his traditional platforms for his last outing, 1992’s Crystal Kingdom Dizzy. |