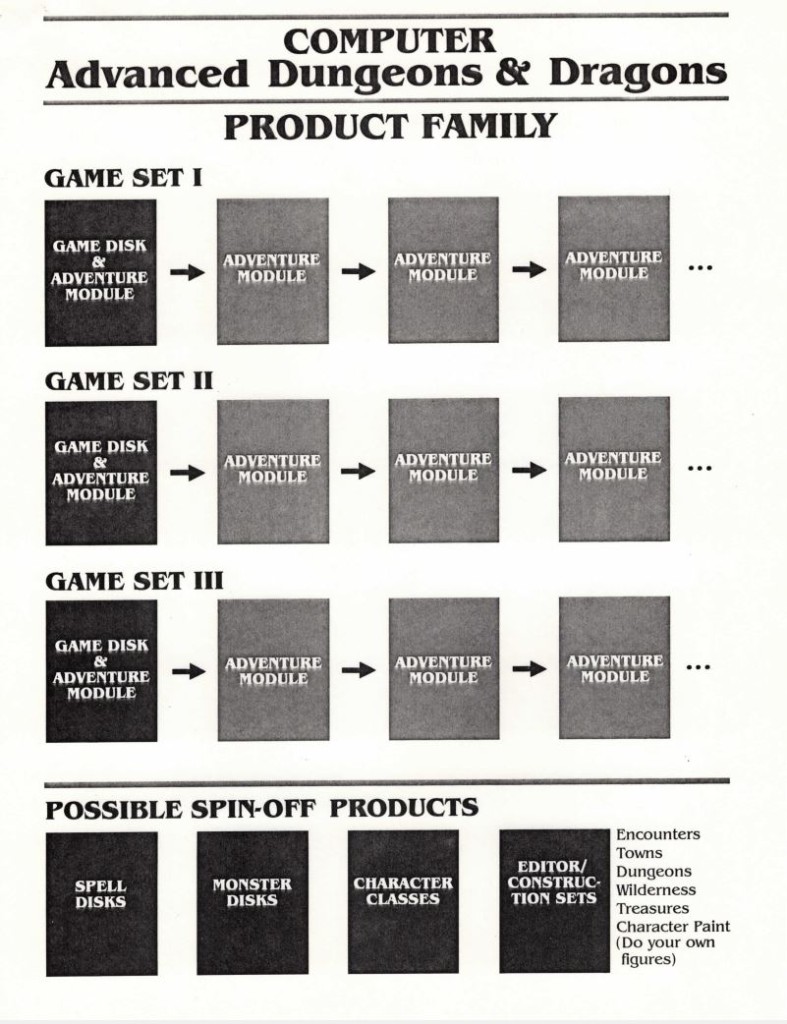

SSI entered 1989 a transformed company. What had been a niche maker of war games for grognards had now become one of the computer-game industry’s major players thanks to the first fruits of the coveted TSR Dungons & Dragons license. Pool of Radiance, the first full-fledged Dungeons & Dragons CRPG and the first in a so-called “Gold Box” line of same, was comfortably outselling the likes of Ultima V and The Bard’s Tale III, and was well on its way to becoming SSI’s best-selling game ever by a factor of four. To accommodate their growing employee rolls, SSI moved in 1989 from their old offices in Mountain View, California, which had gotten so crowded that some people were forced to work in the warehouse using piles of boxed games for desks, to much larger, fancier digs in nearby Sunnyvale. Otherwise it seemed that all they had to do was keep on keeping on, keep on riding Dungeons & Dragons for all it was worth — and, yes, maybe release a war game here and there as well, just for old times’ sake.

One thing that did become more clear than ever over the course of the year, however, was that not all Dungeons & Dragons products were created equal. Dungeon Masters Assistant Volume II: Characters & Treasures sold just 13,516 copies, leading to the quiet ending of the line of computerized aids for the tabletop game that had been one of the three major pillars of SSI’s original plans for Dungeons & Dragons. A deviation from that old master plan called War of the Lance, an attempt to apply SSI’s experience with war games to TSR’s Dragonlance campaign setting, did almost as poorly, selling 15,255 copies. Meanwhile the second of the “Silver Box” line of action-oriented games that made up the second of the pillars continued to perform well: Dragons of Flame sold 55,711 copies. Despite that success, though, 1989 would also mark the end of the line for the Silver Box, due to a breakdown in relations with the British developers behind those games. Going into the 1990s, then, Dungeons & Dragons on the computer would be all about the Gold Box line of turn-based traditional CRPGs, the only one of SSI’s three pillars still standing.

Thankfully, what Pool of Radiance had demonstrated in 1988 the events of 1989 would only confirm. What players seemed to hunger for most of all in the context of Dungeons & Dragons on the computer was literally Dungeons & Dragons on the computer: big CRPGs that implemented as many of the gnarly details of the rules as possible. Even Hillsfar, a superfluous and rather pointless sort of training ground for characters created in Pool of Radiance, sold 78,418 copies when SSI released it in March as a stopgap to give the hardcore something to do while they waited for the real Pool sequel.

They didn’t have too long to wait. The big sequel dropped in June in the form of Curse of the Azure Bonds, and it mostly maintained the high design standard set by Pool of Radiance. Contrarians could and did complain that the free-roaming wilderness map of its predecessor had been replaced by a simple menu of locations to visit, but for this player anyway Pool‘s overland map always felt more confusing than necessary. A more notable loss in my view is the lack of any equivalent in Curse to the satisfying experience of slowly reclaiming the village of Phlan block by block from the forces of evil in Pool, but that brilliant design stroke was perhaps always doomed to be a one-off. Ditto Pool‘s unique system of quests to fulfill, some of them having little or nothing to do with the main plot.

What players did get in Curse of the Azure Bonds was the chance to explore a much wider area around Phlan with the same characters they had used last time, fighting a selection of more powerful and interesting monsters appropriate to their party’s burgeoning skills. At the beginning of the game, the party wakes up with a set of tattoos on their bodies — the “azure bonds” of the title — and no memory of how they got there. (I would venture to guess that many of us have experienced something similar at one time or another…) It turns out that the bonds can be used to force the characters to act against their own will. Thus the quest is on to get them removed; each of the bonds has a different source, corresponding to a different area you will need to visit and hack and slash your way through in order to have it removed. By the end of Curse, your old Pool characters — or the new ones you created just for this game, who start at level 5 — will likely be in the neighborhood of levels 10 to 12, just about the point in Dungeons & Dragons where leveling up begins to lose much of its interest.

TSR was once again heavily involved in the making of Curse of the Azure Bonds, if not quite to the same extent as Pool of Radiance. As they had for Pool, they provided for Curse an official tie-in novel and tabletop adventure module. I can’t claim to have understood all of the nuances of the plot, such as they are, when I played the game; a paragraph book is once again used, but much of what I was told to read consisted of people that I couldn’t remember or never knew who they were babbling on about stuff I couldn’t remember or never knew what it was. But then, I know nothing about the Forgotten Realms setting other than what I learned in Pool of Radiance and never read the novel, so I’m obviously not the ideal audience. (Believe me, readers, I’ve done some painful things for this blog, but reading a Dungeons & Dragons novel was just a bridge too far…) Still, my cluelessness never interfered with my pleasure in mapping out each area and bashing things with my steadily improving characters; the standard of design in Curse remains as high as the writing remains breathlessly, entertainingly overwrought. Curse of the Azure Bonds did almost as well as its predecessor for SSI, selling 179,795 copies and mostly garnering the good reviews it deserved.

It was only with the third game of the Pool of Radiance series, 1990’s Secret of the Silver Blades, that some of the luster began to rub off of the Gold Box in terms of design, if not quite yet in that ultimate metric of sales. The reasons that Secret is regarded as such a disappointment by so many players — it remains to this day perhaps the least liked of the entire Gold Box line — are worth dwelling on for a moment.

One of the third game’s problems is bound up inextricably with the Dungeons & Dragons rules themselves. Secret of the Silver Blades allows you to take your old party from Pool of Radiance and/or Curse of the Azure Bonds up to level 15, but by this stage gaining a level is vastly less interesting than it was back in the day. Mostly you just get a couple of hit points, some behind-the-scenes improvements in to-hit scores, and perhaps another spell slot or two somewhere. Suffice to say that there’s no equivalent to, say, that glorious moment when you first gain access to the Fireball spell in Pool of Radiance.

The tabletop rules suggest that characters who reach such high levels should cease to concern themselves with dungeon delving in lieu of building castles and becoming generals or political leaders. Scorpia, Computer Gaming World‘s adventure and CRPG columnist, was already echoing these sentiments in the context of the Pool of Radiance series at the conclusion of her article on Curse of the Azure Bonds: “Characters have reached (by game’s end) fairly high levels, where huge amounts of experience are necessary to advance. If character transfer is to remain a part of the series (which I certainly hope it does), then emphasis needs to be placed on role-playing, rather than a lot of fighting. The true heart of AD&D is not rolling the dice, but the relationship between the characters and their world.” But this sort of thing, of course, the Gold Box engine was utterly unequipped to handle. In light of this, SSI probably should have left well enough alone, making Curse the end of the line for the Pool characters, but players were strongly attached to the parties they’d built up and SSI for obvious reasons wanted to keep them happy. In fact, they would keep them happy to the tune of releasing not just one but two more games which allowed players to use their original Pool of Radiance parties. By the time these characters finally did reach the end of the line, SSI would have to set them against the gods themselves in order to provide any semblance of challenge.

But by no means can all of the problems with Secret of the Silver Blades be blamed on high-level characters. The game’s other issues provide an interesting example of the unanticipated effects which technical affordances can have on game design, as well as a snapshot of changing cultures within both SSI and TSR.

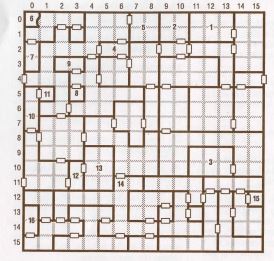

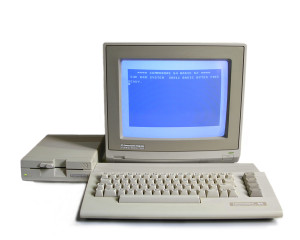

A Gold Box map is built on a grid of exactly 16 by 16 squares, some of which can be “special” squares. When the player’s party enters one of the latter, a script runs to make something unusual happen — from something as simple as some flavor text appearing on the screen to something as complicated as an encounter with a major non-player character. The amount of special content allowed on any given map is restricted, however, by a limitation, stemming from the tiny memories of 8-bit machines like the Commodore 64 and Apple II, on the total size of all of the scripts associated with any given map.

The need for each map to be no larger than 16 by 16 squares couldn’t help but have a major effect on the designs that were implemented with the Gold Box engine. In Pool of Radiance, for example, the division of the city of Phlan into a set of neat sections, to be cleared out and reclaimed one by one, had its origins as much in these technical restrictions as it did in design methodology. In that case it had worked out fantastically well, but by the time development began on Secret of the Silver Blades all those predictably uniform square maps had begun to grate on Dave Shelley, that game’s lead designer. Shelley and his programmers thus came up with a clever way to escape the system of 16 by 16 dungeons.

One of the things a script could do was to silently teleport the player’s party to another square on the map. Shelley and company realized that by making clever use of this capability they could create dungeon levels that gave the illusion of sprawling out wildly and asymmetrically, like real underground caverns would. Players who came into Secret of the Silver Blades expecting the same old 16 by 16 grids would be surprised and challenged. They would have to assume that the Gold Box engine had gotten a major upgrade. From the point of view of SSI, this was the best kind of technology refresh: one that cost them nothing at all. Shelley sketched out a couple of enormous underground complexes for the player to explore, each larger almost by an order of magnitude than anything that had been seen in a Gold Box game before.

A far less neat map from Secret of the Silver Blades. It may be more realistic in its way, but which would you rather try to draw on graph paper? It may help you to understand the scale of this map to know that the large empty squares at the bottom and right side of this map each represent a conventional 16 by 16 area like the one shown above.

But as soon as the team began to implement the scheme, the unintended consequences began to ripple outward. Because the huge maps were now represented internally as a labyrinth of teleports, the hugely useful auto-map had to be disabled for these sections. And never had the auto-map been needed more, for the player who dutifully mapped the dungeons on graph paper could no longer count on them being a certain size; they were constantly spilling off the page, forcing her to either start over or go to work on a fresh page stuck onto the old with a piece of tape. Worst of all, placing all of those teleports everywhere used just about all of the scripting space that would normally be devoted to providing other sorts of special squares. So, what players ended up with was an enormous but mind-numbingly boring set of homogeneous caverns filled with the same handful of dull random-monster encounters, coming up over and over and over. This was not, needless to say, an improvement on what had come before. In fact, it was downright excruciating.

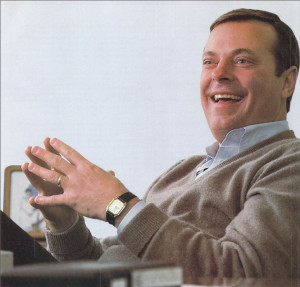

At the same time that this clever technical trick was pushing the game toward a terminal dullness, other factors were trending in the same direction. Shelley himself has noted that certain voices within SSI were questioning whether all of those little extras found in Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds, like the paragraph books and the many scripted special encounters, were really necessary at all — or, at the least, perhaps it wasn’t necessary to do them with quite so much loving care. SSI was onto a good thing with these Gold Box games, said these voices — found mainly in the marketing department — and they ought to strike while the iron was hot, cranking them out as quickly as possible. While neither side would entirely have their way on the issue, the pressure to just make the games good enough rather than great in order to get them out there faster can be sensed in every Gold Box game after the first two. More and more graphics were recycled; fewer and fewer of those extra, special touches showed up. SSI never fully matched Pool of Radiance, much less improved on it, over the course of the ten Gold Box games that followed it. That SSI’s founder and president Joel Billings, as hardcore a gamer as any gaming executive ever, allowed this stagnation to take root is unfortunate, but isn’t difficult to explain. His passion was for the war games he’d originally founded SSI to make; all this Dungeons & Dragons stuff, while a cash cow to die for, was largely just product to him.

A similar complaint could be levied — and has been levied, loudly and repeatedly, by legions of hardcore Dungeons & Dragons fans over the course of decades — against Lorraine Williams, the wealthy heiress who had instituted a coup against Gary Gygax in 1985 to take over TSR. The idea that TSR’s long, slow decline and eventual downfall is due solely to Williams is more than a little dubious, given that Gygax and his cronies had already done so much to mismanage the company down that path before she ever showed up. Still, her list of wise strategic choices, at least after her very wise early decision to finally put Dungeons & Dragons on computers, is not a long one.

At the time they were signing the contract with SSI, TSR had just embarked on the most daunting project in the history of the company: a project to reorganize the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules, which had sprawled into eight confusing and sometimes contradictory hardcover books by that point, into a trio of books of relatively streamlined and logically organized information, all of it completely rewritten in straightforward modern English (as opposed to the musty diction of Gary Gygax, which read a bit like a cross of Samuel Johnson with H.P. Lovecraft). The fruits of the project appeared in 1989 in the form of a second-edition Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, and Monstrous Compendium.

And then, right after expending so much effort to clean things up, TSR proceeded to muddy the second-edition waters even more indiscriminately than they had those of the first edition. Every single character class got its own book, and players with a hankering to play Dungeons & Dragons as a Viking or one of Charlemagne’s paladins were catered to. Indeed, TSR went crazy with campaign settings. By 1993, boxed sets were available to let you play in the Forgotten Realms, in the World of Greyhawk, or in Dragonlance‘s world of Krynn, or to play the game as a Jules Verne-esque science-fiction/fantasy hybrid called Spelljammer. You could also play Dungeons & Dragons as Gothic horror if you bought the Ravenloft set, as vaguely post-apocalyptic dark fantasy if you bought Dark Sun, as a set of tales from the Arabian Nights if you bought Al-Qadim, or as an exercise in surreal Expressionism worthy of Alfred Kubin if you bought Planescape.

Whatever the artistic merits behind all these disparate approaches — and some of them did, it should be said, have much to recommend them over the generic cookie-cutter fantasy that was vanilla Dungeons & Dragons — the commercial pressures that led Lorraine Williams to approve this glut of product aren’t hard to discern. The base of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons players hadn’t grown appreciably for many years. Just the opposite, in fact: it’s doubtful whether even half as many people were actively playing Dungeons & Dragons in 1990 as at the height of the brief-lived fad for the game circa 1982. After the existing player base had dutifully rushed out to buy the new second-edition core books, in other words, very few new players were discovering the game and thus continuing to drive their sales. Unless and until they could find a way to change that situation, the only way for TSR to survive was to keep generating gobs of new product to sell to their existing players. Luckily for them, hardcore Dungeons & Dragons players were tremendously loyal and tremendously dedicated to their hobby. Many would buy virtually everything TSR put out, even things that were highly unlikely ever to make it to their gaming tables, just out of curiosity and to keep up with the state of the art, as it were. It would take two or three years for players to start to evince some fatigue with the sheer volume of product pouring out of TSR’s Lake Geneva offices, much of it sorely lacking in play-testing and basic quality control, and to start giving large swathes of it a miss — and that, in turn, would spell major danger for TSR’s bottom line.

Lorraine Williams wasn’t unaware of the trap TSR’s static customer base represented; on the contrary, she recognized as plainly as anyone that TSR needed to expand into new markets if it was to have a bright long-term future. She made various efforts in that direction even as her company sustained itself by flooding the hardcore Dungeons & Dragons market. In fact, the SSI computer games might be described as one of these efforts — but even those, successful as they were on their own terms, were still playing at least partially to that same old captive market. In 1989, Williams opened a new TSR office on the West Coast in an attempt to break the company out of its nerdy ghetto. Run by Flint Dille, Williams’s brother, one of TSR West’s primary goals was to get Dungeons & Dragons onto television screens or, better yet, onto movie screens. Williams was ironically pursuing the same chimera that her predecessor Gary Gygax — now her sworn, lifetime arch-enemy — had so zealously chased. She was even less successful at it than he had been. Whereas Gygax had managed to get a Saturday morning cartoon on the air for a few seasons, Flint Dille’s operation managed bupkis in three long years of trying.

Another possible ticket to the mainstream, to be pursued every bit as seriously in Hollywood as a Dungeons & Dragons deal, was Buck Rogers, the source of the shared fortune of Lorraine Williams and Flint Dille. Their grandfather had been John F. Dille, owner of a newspaper syndicator known as the National Newspaper Service. In this capacity, the elder Dille had discovered the character that would become Buck Rogers — at the time, he was known as Anthony Rogers — in Armageddon 2419 A.D., a pulp novella written by Philip Francis Nowlan and published in Amazing Stories in 1928. Dille himself had come up with the nickname of “Buck” for the lead character, and convinced Nowlan to turn his adventures in outer space into a comic strip for his syndicator. It ended up running from 1929 until 1967 — only the first ten of those years under the stewardship of Nowlan — and was also turned into very popular radio and movie serials during the 1930s, the height of the character’s popularity. Having managed to secure all of the rights to Buck from a perhaps rather naive Nowlan, John Dille and his family profited hugely.

In marked contrast to her attitude toward TSR’s other intellectual properties, Lorraine Williams’s determination to return Buck Rogers to the forefront of pop culture was apparently born as much from a genuine passion for her family’s greatest legacy as it was from the dispassionate calculus of business. In addition to asking TSR West to lobby — once again fruitlessly, as it would transpire — for a Buck Rogers revival on television or film, she pushed a new RPG through the pipeline, entitled Buck Rogers XXVc and published in 1990. TSR supported the game fairly lavishly for several years in an attempt to get it to take off, releasing source books, adventure modules, and tie-in novels to little avail. With all due deference to Buck Rogers’s role as a formative influence on Star Wars among other beloved contemporary properties, in the minds of the Dungeons & Dragons generation it was pure cheese, associated mainly with the Dille family’s last attempt to revive the character, the hilariously campy 1979 television series Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. The game might have had a chance with some players had Williams been willing to recognize the cheese factor and let her designers play it up, but taken with a straight face? No way.

SSI as well was convinced — or coerced — to adapt the Gold Box engine from fantasy to science fiction for a pair of Buck Rogers computer games, 1990’s Countdown to Doomsday and 1992’s Matrix Cubed. SSI’s designers must have breathed a sigh of relief when they saw that the rules for the Buck Rogers tabletop RPG, much more so than any of TSR’s previous non-Dungeons & Dragons RPGs, had been based heavily on those of the company’s flagship game; thus the process of adaptation wasn’t quite so onerous as it might otherwise have been. That said, most agree that the end results are markedly less interesting than the other Gold Box games when it comes to combat, the very thing at which the engine normally excels; a combat system designed to include magic becomes far less compelling in its absence. Benefiting doubtless from its association with the Dungeons & Dragons Gold Box line, for which enthusiasm remained fairly high, the first Buck Rogers game sold a relatively healthy 51,528 copies; the second managed a somewhat less healthy 38,086 copies.

All of these competing interests do much to explain why TSR, after involving themselves so closely in the development of Pools of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds, withdrew from the process almost entirely after those games and just left SSI to it. And that fact in turn is yet one more important reason why the Gold Box games not only failed to evolve but actually devolved in many ways. TSR’s design staff might not have had a great understanding of computer technology, but they did understand their settings and rules, and had pushed SSI to try to inject at least a little bit of what made for a great tabletop-role-playing experience into the computer games. Absent that pressure, SSI was free to fall back on what they did best — which meant, true to their war-game roots, lots and lots of combat. In both Pool and Curse, random encounters cease on most maps after you’ve had a certain number of them — ideally, just before they get boring. Tellingly, in Secret of the Silver Blades and most of the other later Gold Box games that scheme is absent. The monsters just keep on coming, ad infinitum.

Despite lukewarm reviews that were now starting to voice some real irritation with the Gold Box line’s failure to advance, Secret of the Silver Blades was another huge hit, selling 167,214 copies. But, in an indication that some of those who purchased it were perhaps disappointed enough by the experience not to continue buying Gold Box games, it would be the last of the line to break the 100,000-copy barrier. The final game in the Pool of Radiance series, Pools of Darkness, sold just 52,793 copies upon its release in 1991.

In addition to the four-game Pool series, SSI also released an alternate trilogy of Dungeons & Dragons Gold Box games set in Krynn, the world of the Dragonlance setting. Champions of Krynn was actually released before Secret of the Silver Blades, in January of 1990, and sold 116,693 copies; Death Knights of Krynn was released in 1991 and sold 61,958 copies; and The Dark Queen of Krynn, the very last Gold Box game, was released in 1992 and sold 40,640 copies. Another modest series of two games was developed out-of-house by Beyond Software (later to be renamed Stormfront Studios): Gateway to the Savage Frontier (1991, 62,581 copies sold) and Treasures of the Savage Frontier (1992, 31,995 copies sold). In all, then, counting the two Buck Rogers games but not counting the oddball Hillsfar, SSI released eleven Gold Box games over a period of four years.

While Secret of the Silver Blades still stands as arguably the line’s absolute nadir in design terms, the sheer pace at which SSI pumped out Gold Box games during the latter two years of this period in particular couldn’t help but give all of them a certain generic, interchangeable quality. It all began to feel a bit rote — a bit cheap, in stark contrast to the rarefied atmosphere of a Big Event that had surrounded Pool of Radiance, a game which had been designed and marketed to be a landmark premium product and had in turn been widely perceived as exactly that. Not helping the line’s image was the ludicrous knockoff-Boris Vallejo cover art sported by so many of the boxes, complete with lots of tawny female skin and heaving bosoms. Susan Manley has described the odd and somewhat uncomfortable experience of being a female artist asked to draw this sort of stuff.

They pretty much wanted everybody [female] to be the chainmail-bikini babes, as we called them. I said, “Look, not everybody wants to be a chainmail-bikini babe.” They said, “All the guys want that, and we don’t have very many female players.” I said, “You’re never going to have female players if you continue like this. Functional armor that would actually protect people would play a little bit better.”

Tom [Wahl, SSI’s lead artist] and I actually argued over whether my chest size was average or not, which was an embarrassing conversation to have. He absolutely thought that everybody needed to look like they were stepping out of a Victoria’s Secret catalog if they were female. I said, “Gee, how come all the guys don’t have to be super-attractive?” They don’t look like they’re off of romance-novel covers, let’s put it that way. They get to be rugged, they get to be individual, they get to all have different costumes. They get to all have different hairstyles, but the women all had to have long, flowing locks and lots of cleavage.

By 1991, the Gold Box engine was beginning to seem rather like a relic from technology’s distant past. In a sense, the impression was literally correct. When SSI had begun to build the Gold Box engine back in 1987, the Commodore 64 had still ruled the roost of computer gaming, prompting SSI to make the fateful decision not only to make sure the Gold Box games could run on that sharply limited platform, but also to build most of their development tools on it. Pool of Radiance then appeared about five minutes before the Commodore 64’s popularity imploded in the face of Nintendo. The Gold Box engine did of course run on other platforms, but it remained throughout its life subject to limitations born of its 8-bit origins — things like the aforementioned maps of exactly 16 by 16 squares and the strict bounds on the amount of custom scripting that could be included on a single one of those maps. Even as the rest of the industry left the 8-bit machines behind in 1989 and 1990, SSI was reluctant to do so in that the Commodore 64 still made up a major chunk of Gold Box sales: Curse of the Azure Bonds sold 68,622 copies on the Commodore 64, representing more than a third of its total sales, while Secret of the Silver Blades still managed a relatively healthy 40,425 Commodore 64 versions sold. Such numbers likely came courtesy of diehard Commodore 64 owners who had very few other games to buy in an industry that was moving more and more to MS-DOS as its standard platform. SSI was thus trapped for some time in something of a Catch-22, wanting to continue to reap the rewards of being just about the last major American publisher to support the Commodore 64 but having to compromise the experience of users with more powerful machines in order to do so.

SSI had managed to improve the Gold Box graphics considerably by the time of The Dark Queen of Krynn, the last game in the line.

When SSI finally decided to abandon the Commodore 64 in 1991, they did what they could to enhance the Gold Box engine to take advantage of the capabilities of the newer machines, introducing more decorative displays and pictures drawn in 256-color VGA along with some mouse support. Yet the most fundamental limitations changed not all; the engine was now aged enough that SSI wasn’t enthused about investing in a more comprehensive overhaul. And thus the Gold Box games seemed more anachronistic than ever. As SSI’s competitors worked on a new generation of CRPGs that took advantage of 32-bit processors and multi-megabyte memories, the Gold Box games remained the last surviving relics of the old days of 8 bits and 64 K. Looking at The Dark Queen of Krynn and the technical tour de force that was Origin’s Ultima VII side by side, it’s difficult to believe that the two games were released in the same year, much less that they were, theoretically at least, direct competitors.

It’s of course easy for us to look back today and say what SSI should have done. Instead of flooding the market with so many generic Gold Box games, they should have released just one game every year or eighteen months, each release reflecting a much more serious investment in writing and design as well as real, immediately noticeable technical improvements. They should, in other words, have strained to make every new Gold Box game an event like Pool of Radiance had been in its day. But this had never been SSI’s business model; they had always released lots of games, very few of which sold terribly well by the standard of the industry at large, but whose sales in the aggregate were enough to sustain them. When, beginning with Pool of Radiance, they suddenly were making hits by anybody’s standards, they had trouble adjusting their thinking to their post-Pool situation, had trouble recognizing that they could sell more units and make more money by making fewer but better games. Such is human nature; making such a paradigm shift would doubtless challenge any of us.

Luckily, just as the Gold Box sales began to tail off SSI found an alternative approach to Dungeons & Dragons on the computer from an unlikely source. Westwood Associates was a small Las Vegas-based development company, active since 1985, who had initially made their name doing ports of 8-bit titles to more advanced machines like the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST (among these projects had been ports of Epyx’s Winter Games, World Games, and California Games). What made Westwood unique and highly sought after among porters was their talent for improving their 8-bit source material enough, in terms of both audiovisuals and game play, that the end results would be accepted almost as native sons by the notoriously snobbish owners of machines like the Amiga. Their ambition was such that many publishers came to see the biggest liability of employing them as a tendency to go too far, to such an extent that their ports could verge on becoming new games entirely; for example, their conversion of Epyx’s Temple of Apshai on the Macintosh from turn-based to real-time play was rejected as being far too much of a departure.

Westwood first came to the attention of Gold Box fans when they were given the job of implementing Hillsfar, the stopgap “character training grounds” which SSI released between Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds. Far more auspicious were Westwood’s stellar ports of the mainline Gold Box games to the Amiga, which added mouse support and improved the graphics well before SSI’s own MS-DOS versions made the leap to VGA. But Brett Sperry and Louis Castle, Westwood’s founders, had always seen ports merely as a way of getting their foot in the door of the industry. Already by the time they began working with SSI, they were starting to do completely original games of their own for Electronic Arts and Mediagenic/Activision. (Their two games for the latter, both based on a board-game line called BattleTech, were released under the Infocom imprint, although the “real” Cambridge-based Infocom had nothing to do with them.) Westwood soon convinced SSI as well to let them make an original title alongside the implementation assignments: what must be the strangest of all the SSI Dungeons & Dragons computer games, a dragon flight simulator (!) called Dragon Strike. Released in 1990, it wasn’t quite an abject flop but neither was it a hit, selling 34,296 copies. With their next original game for SSI, however, Westwood would hit pay dirt.

Eye of the Beholder was conceived as Dungeons & Dragons meets Dungeon Master, bringing the real-time first-person game play of FTL’s seminal 1987 dungeon crawl to SSI’s product line. In a measure of just how ahead-of-its-time Dungeon Master had been in terms not only of technology but also of fundamental design, nothing had yet really managed to equal it over the three years since its release. Eye of the Beholder arguably didn’t fully manage that feat either, but it did at the very least come closer than most other efforts — and of course it had the huge advantage of the Dungeons & Dragons license. When a somewhat skeptical SSI sent an initial shipment of 20,000 copies into the distribution pipeline in February of 1991, “they all disappeared” in the words of Joel Billings: “We put them out and boom!, they were gone.” Eye of the Beholder went on to sell 129,234 copies, nicely removing some of the sting from the slow commercial decline of the Gold Box line and, indeed, finally giving SSI a major Dungeons & Dragons hit that wasn’t a Gold Box game. The inevitable sequel, released already in December of 1991, sold a more modest but still substantial 73,109 copies, and a third Eye of the Beholder, developed in-house this time at SSI, sold 50,664 copies in 1993. The end of the line for this branch of the computerized Dungeons & Dragons family came with the pointless Dungeon Hack, a game that, as its name implies, presented its player with an infinite number of generic randomly generated dungeons to hack her way through; it sold 27,110 copies following its release at the end of 1993.

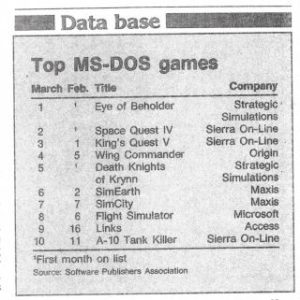

This chart from the April 1991 Software Publishers Association newsletter shows just how quickly Eye of the Beholder took off. Unfortunately, this would mark the last time an SSI Dungeons & Dragons game would be in this position.

Despite their popularity in their heyday, the Eye of the Beholder games in my view have aged less gracefully than their great progenitor Dungeon Master, or for that matter even the early Gold Box games. If what you wished for more than anything when playing Dungeon Master was lots more — okay, any — story and lore to go along with the mapping, the combat, and the puzzles, these may be just the games for you. For the rest of us, though, the Dungeons & Dragons rules make for an awkward fit to real-time play, especially in contrast to Dungeon Master‘s designed-from-scratch-for-real-time systems of combat, magic, and character development. The dungeon designs and even the graphics similarly underwhelm; Eye of the Beholder looks a bit garish today in contrast to the clean minimalism of Dungeon Master. The world would have to wait more than another year, until the release of Ultima Underworld, to see a game that truly and comprehensively improved on the model of Dungeon Master. In the meantime, though, the Eye of the Beholder games would do as runners-up for folks who had played Dungeon Master and its sequel and still wanted more, or for those heavily invested in the Dungeons & Dragons rules and/or the Forgotten Realms setting.

For SSI, the sales of the Eye of the Beholder games in comparison to those of the latest Gold Box titles provided all too clear a picture of where the industry was trending. Players were growing tired of the Gold Box games; they hungered after faster-paced CRPGs that were prettier to look at and easier to control. While Eye of the Beholder was still high on the charts, TSR and SSI agreed to extend their original five-year contract, which was due to expire on January 1, 1993, by eighteen months to mid-1994. The short length of the extension may be indicative of growing doubts on the part of TSR about SSI’s ability to keep up with the competition in the CRPG market; one might see it as a way of putting them on notice that the TSR/SSI partnership was by no means set in stone for all time. At any rate, a key provision of the extension was that SSI must move beyond the fading Gold Box engine, must develop new technology to suit the changing times and to try to recapture those halcyon early days when Pool of Radiance ruled the charts and the world of gaming was abuzz with talk of Dungeons & Dragons on the computer. Accordingly, SSI put a bow on the Gold Box era in March of 1993 with the release of Unlimited Adventures, a re-packaging of their in-house development tools that would let diehard Gold Box fans make their own games to replace the ones SSI would no longer be releasing. It sold just 32,362 copies, but would go on to spawn a loyal community of adventure-makers that to some extent still persists to this day. As for what would come next for computerized Dungeons & Dragons… well, that’s a story for another day.

By way of wrapping up today’s story, I should note that my take on the Gold Box games, while I believe it dovetails relatively well with the consensus of the marketplace at the time, is by no means the only one in existence. A small but committed group of fans still loves these games — yes, all of them — for their approach to tactical combat, which must surely mark the most faithful implementation of the tabletop game’s rules for same ever to make it to the computer. “It’s hard to imagine a truly bad game being made with it,” says blogger Chester Bolingbroke — better known as the CRPG Addict — of the Gold Box engine. (Personally, I’d happily nominate Secret of the Silver Blades for that designation.)

Still, even the Gold Box line’s biggest fans will generally acknowledge that the catalog is very front-loaded in terms of innovation and design ambition. For those of you like me who aren’t CRPG addicts, I highly recommend Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds, which together let you advance the same party of characters just about as far as remains fun under the Dungeons & Dragons rules, showing off the engine at its best in the process. If the Gold Box games that came afterward wind up a bit of an anticlimactic muddle, we can at least still treasure those two genuine classics. And if you really do want more Gold Box after playing those two, Lord knows there’s plenty of it out there, enough to last most sane people a lifetime. Just don’t expect any of it to quite rise to the heights of the first games and you’ll be fine.

(Sources: This article is largely drawn from the collection of documents that Joel Billings donated to the Strong Museum of Play, which includes lots of internal SSI documents and some press clippings. Also, the book Designers & Dragons Volume 1 by Shannon Appelcline; Computer Gaming World of September 1989; Retro Gamer 52 and 89; Matt Barton’s video interviews with Joel Billings, Susan Manley, and Dave Shelley and Laura Bowen.

Many of the Gold Box games and the Eye of the Beholder trilogy are available for purchase from GOG.com. You may also wish to investigate The Gold Box Companion, which adds many modern conveniences to the original games.)