We have a fair number of games and events still to cover in the ongoing history of Infocom that’s been biting such a good-sized chunk out of this blog for so long, but the end is slowly heaving into sight. The same was also true, albeit in a less certain and more intuitive way, for those actually at Infocom at the time of The Lurking Horror‘s release. The winds of the industry were quite clearly blowing against them, and even if they could manage to eke out another hit or two it wasn’t at all clear how they could remake themselves to conform to the new order in the longer term. Meanwhile some of the Imps were beginning to wonder what the point of surviving as a developer of interactive fiction might be anyway. They knew how to make rock-solid text adventures in their traditional style, but they didn’t quite know how to advance beyond that. Given that they were unlikely to ever make a better game in that traditional style than Trinity, and that their players had proved unreceptive to their one attempt to radically upend the formula with A Mind Forever Voyaging, that was a problem. Infocom wasn’t populated by the sort of people who are comfortable just reworking the status quo year after year.

All of these feelings must have fed into David Lebling’s decision to set his game for 1987 at a lovingly recreated MIT, known as GUE Tech in the game. With commercial pressures threatening to crush an Infocom that had long since lost control of their own destiny and artistic ennui threatening to crush the Imps’ souls as well, it was nice to think back to the simpler days at MIT where it had all begun as just another hacking exercise, where that original mainframe Zork had represented for Lebling and his earliest co-Implementors something so inspiring and genuinely new under the sun. By way of honoring those feelings, I thought we could also take one last lingering look back along with Lebling today. I’d like to take you on a guided tour through The Lurking Horror‘s MIT… oops, GUE. If you haven’t played this one before, or if it’s been a while, feel free to play along with me. I won’t solve the puzzles for you — although a little nudge here and there may be in the cards — but I will tell you a bit more about what you’re seeing. For what follows I’m hugely indebted to Janice Eisen (MIT Class of 1985), a Patreon supporter who not only pays me for each of these articles but all but did my job for me when it came to this one by sharing her own experiences of life at MIT as it was then and presumably still is today. So, come along with Janice and me and let us tell you a little about the place where Infocom began.

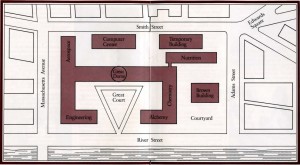

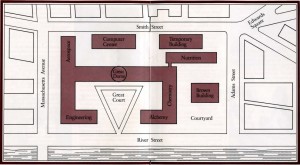

Whether you’re playing along or not, the map found in the center of the GUE Tech brochure that accompanies The Lurking Horror is well worth referring to now and throughout this tour. It roughly corresponds to the heart of the real campus, albeit with some important differences that I’ll be explaining when we come to them. If you’re feeling particularly motivated, you may also want to pull up MIT’s official campus map for comparison purposes. To orient yourself, know that the Great Dome is found on Building 10 on that map.

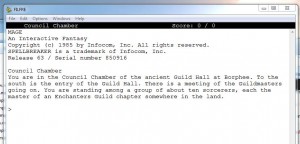

We start our adventurous evening one dark and snowy winter night in GUE Tech’s so-called “Computer Center,” which corresponds to MIT’s Building 13 (an ominous start, no?).

Terminal Room

This is a large room crammed with computer terminals, small computers, and printers. An exit leads south. Banners, posters, and signs festoon the walls. Most of the tables are covered with waste paper, old pizza boxes, and empty Coke cans. There are usually a lot of people here, but tonight it's almost deserted.

A really whiz-bang pc is right inside the door.

Nearby is one of those ugly molded plastic chairs.

Sitting at a terminal is a hacker whom you recognize.

Know first of all that this is not the place where so many future Infocom staffers worked throughout the 1970s, and created Zork near the end of that decade. That game was born on the second floor of a building some distance to the north of the campus core, described by Steven Levy in his seminal Hackers as “a building of mind-numbing dullness, with no protuberances and sill-less windows that looked painted onto its off-white surface.” It still looks about the same today, and houses MIT’s Center for Biomedical Engineering and Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies among other tenants. Building 13, meanwhile, is not and never has been earmarked as a computer center; it houses the Material Sciences and Engineering Center among others.

That said, the description of the place, unholy mess included, is very typical of the computer labs that were and are scattered all over the campus. The hacker who inhabits it alongside us is certainly worth a look.

>examine hacker

The hacker sits comfortably on an office chair facing a terminal table, or perhaps it's just a pile of old listings as tall as a terminal table. He is typing madly, using just two fingers, but achieves speeds that typists using all ten fingers only dream of. He is apparently debugging a large assembly language program, as the screen of his terminal looks like a spray of completely random characters. The hacker is dressed in blue jeans, an old work shirt, and what might once have been running shoes. Hanging from his belt is an enormous ring of keys. He is in need of a bath.

It’s instructive to compare this depiction of a prototypical hacker — i.e., practically Richard Stallman in the flesh — with Michael Bywater’s “horrible nerd” from Bureaucracy. Lebling, while certainly not blind to his character’s annoying eccentricities, also shows a knowing familiarity that borders on affection. Bywater… doesn’t. Particularly knowing on Lebling’s part is the hacker’s typing ability, or if you like the lack thereof. Hackers have always looked on proper ten-fingered typing as a sure sign that the person in question is not one of them.

Richard Stallman

I trust I’m not giving too much away if I mention that that “enormous ring of keys” will become a critical part of the game. Strange as it may sound, keys, the more exotic the better, are in fact a status symbol at MIT. Keys imply knowledge of and access to the labyrinthine tunnels and cubbyholes that riddle the campus. “Roof-and-tunnel hacking,” something we ourselves will be indulging in on this snowy night, has always been a popular pastime at MIT, tolerated if not officially condoned by the administration and campus police — tolerated not least thanks to the fact that, contrary to The Lurking Horror‘s GUE Tech brochure, no known deaths can be attributed to the practice. Janice told me the story of joining a “very unofficial student-run tour of the roofs and tunnels” as a freshman. After making their way down a creepy old steam tunnel, they popped out through a grating in a sidewalk right in front of a campus policeman. “You’re not supposed to be in there! Go back the way you came!” he ordered, leaving them no choice but to scurry back down the tunnel. One can imagine a self-satisfied character like our hacker here leading just such a tour, flaunting his knowledge and his enormous ring of keys before the newbies.

The word “hack” itself originated at MIT, where it originally implied both campus explorations of the sort just described and the sort of clever and usually elaborate practical jokes in which MIT students, once again with the tacit acceptance of the campus police and administration, have always indulged. In time anything done in an original, clever, and/or cheeky way came to be called a “hack.” By the 1960s it was being applied to computing at MIT, to the burgeoning culture of unrepentant oddballs who spent their lives trying to make these strange new machines run better, faster, and smarter. As former MIT hackers got jobs in private business and accepted postings at other universities, the usage became universal.

But we do have an assignment to write, so let’s see what we’re up against.

>examine assignment

Laser printed on creamy bond paper, the assignment is due tomorrow. It's from your freshman course in "The Classics in the Modern Idiom," better known as "21.014." It reads, in part: "Twenty pages on modern analogues of Xenophon's 'Anabasis.'" You're not sure whether this refers to the movie "The Warriors" or "Alien," but this is the last assignment you need to complete in this course this term. You wonder, yet again, why a technical school requires you to endure this sort of stuff.

Many an MIT student over the years has doubtless wondered the same thing. Like all accredited American universities, MIT conforms to the “balanced person” ideal of education, which demands that each student take a smattering of humanities and other subjects outside her major during her first year or two at university. Derided as the requirement often is, I tend to feel we could use more balanced people in the world today. The collision between technology and the humanities at MIT in particular has yielded some fascinating results, such as Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck and Nick Montfort’s work in many areas of computational creativity.

Buildings at MIT are, with only a few exceptions, referred to only by their numbers, and the same holds true for courses; thus the “better known” in the passage above is literally accurate. The prefix of “21” does indeed correspond to the Department of Humanities at MIT.

Let’s turn to that “really whiz-bang pc” and see if we can get to work.

>examine pc

This is a beyond-state-of-the-art personal computer. It has a 1024 by 1024 pixel color monitor, a mouse, an attached hard disk, and a local area network connection. Fortunately, one of its features is a prominent HELP key. It is currently turned off.

It’s a bit odd that The Lurking Horror refers to this machine as a PC at all; it’s obviously a workstation-class machine, generally considered a different species entirely from the more humble PC during the 1980s. Not only is this computer far beyond what would have been available to Lebling during his time at MIT, it’s also far beyond what the average student even in 1987 could hope to have at her disposal. It appears to represent a 3M workstation, a term first coined by Carnegie Mellon University professor Raj Reddy in the early 1980s. More of an aspiration than a practicality at that time, a 3M machine demanded at least 1 MB of memory, a display consisting of at least 1 million pixels, and a CPU capable of processing at least 1 million instructions per second. While a few such machines were available by 1987 and others were in the offing — after leaving Apple in 1985, Steve Jobs founded NeXT with this very specification in mind — very few were likely to be at the disposal of ordinary students looking to write Classics papers. Back in Lebling’s day, almost all of the work at the Laboratory for Computer Science was being done on text-only terminals — no mouse, no hard disk, no color, and for that matter no pixels that didn’t form textual characters — attached to a central DEC PDP-10. Indeed, this was largely the way that an increasingly anachronistic Infocom was still working in 1987. Nowadays, of course, a Raspberry Pi blows right past most of the 3M specification and just keeps on going for orders of magnitude afterward.

Let’s log in, shall we?

>turn on pc

The computer powers up, goes through a remarkably fast self-check, and greets you, requesting "LOGIN PLEASE:". The only sound you hear is a very low hum.

>login [you'll have to figure this out for yourself]

The computer responds "PASSWORD PLEASE:"

>type [this too]

The computer responds "Good evening. You're here awfully late." It displays a list of pending tasks, one of which is in blinking red letters, with large arrows pointing to it. The task reads "Classics Paper," some particularly ominous words next to it say "DUE TOMORROW!" and more reassuringly, a menu box next to that reads "Edit Classics Paper."

>click menu box

The menu box is replaced by the YAK text editor and menu boxes listing the titles of your files. The one for your paper is highlighted in a rather urgent-looking shade of red.

The “YAK” text editor is an obvious reference to Richard Stallman’s GNU project, an attempt to create a completely free and open-source operating system that he began at MIT in 1983. One of the tools Stallman brought to the GNU project at its founding was his everything-but-the-kitchen-sink text editor Emacs, a great favorite with hackers to this day. After years of uncertain progress, the utilities developed by Stallman and others for GNU were merged with Linus Torvalds’s new Unix-like kernel in the early 1990s to create the operating system known as “Linux” today — or “GNU/Linux,” as Stallman would undoubtedly correct me. The first two letters in the name of The Lurking Horror‘s YAK editor were and are very common in hacker acronyms, standing for “Yet Another.” As for yet another what in this instance… your guess is as good as mine.

Stallman was at MIT throughout the 1970s, but he worked for the other half of MIT computer research’s split personality, the AI Laboratory rather than the Laboratory for Computer Science. (The names were of little relevance, with the latter often conducting AI research and the former often wandering far afield from it.) His path doesn’t seem to have crossed those of the future Infocom crowd with any great frequency, especially given that the Laboratory for Computer Science always had the reputation of being the more pragmatic and commercially oriented of the two groups. He would have held Infocom in contempt for attempting to market their innovations. Never one to hold back his opinions, Stallman liberally bestowed epithets like “fascist” on those who defied his “free as in freedom” hacker ethics by, say, trying to install a reasonably secure password system onto the campus computer systems.

I’ll leave it to you to read the paper, which turns out to be something very different than expected, and to talk with the hacker about it; be sure to appreciate the “explosion in a teletype factory” line, one of the best Lebling ever wrote. Afterward let’s have a look in the kitchen.

Kitchen

This is a filthy kitchen. The exit is to the east. On the wall near a counter are a refrigerator and a microwave.

Sitting on the kitchen counter is a package of Funny Bones.

>open refrigerator

Opening the refrigerator reveals a two liter bottle of Classic Coke and a cardboard carton.

>x carton

This is a cardboard carton with an incomprehensible symbol scrawled on the top.

>open carton

Opening the cardboard carton reveals Chinese food.

A joke among MIT hackers had it that the four basic food groups were caffeine, sugar, salt, and grease. What with caffeine and sugar getting pride of place even on that list, the infamous switch to the New Coke formula in 1985 hit them particularly hard. When the Coca-Cola Company bowed to popular demand and reintroduced the old formula as “Coke Classic” just a few months later, many hackers latched onto the theory, since disproved, that it was all a big conspiracy to switch out real sugar for high-fructose corn syrup in their favorite drink.

The connection between hacking and Chinese food is just as longstanding. A Chinese menu is a system of flavor combinations that’s infinitely intriguing to a certain kind of mind, and thus MIT hackers have been haunting Boston Chinatown since the late 1950s. Many bought Chinese-English dictionaries in order to translate the Chinese menus that were normally only given to Chinese patrons; these were always much more interesting than the safe choices reserved for English speakers. Yes, sometimes the results of the hackers’ culinary experiments could be vile, but other times they could be magnificent. In a sense it didn’t really matter. It was all just so interesting, yet another fascinating system to hack.

A favorite of the future Infocom staffers, as it was of many MIT hackers, was a place called The House of Roy, presided over by the inimitable Roy himself, whose sense of humor was surprisingly in sync with that of his favorite non-Chinese patrons. I love this anecdote from a regular customer:

We asked for tea and Roy (we think this was the family name) told Suford she would be allowed to go into the kitchen and make it for us. When she returned she informed us that the kitchen was ruled over by a large tom cat. (“Did you pet him?” “No, he was on duty.”) When we queried the owner his response was that the cat kept down vermin and was safer than chemicals. We asked about the Health Inspector and were told “cat cleaner than Health Inspector.”

Roy had only recently died at the time that The Lurking Horror was written, his beloved restaurant closed. Lebling pays tribute to this lost and lamented MIT institution by including it as the only nonfictional “Favorite Hangout” in his GUE Tech brochure.

If we put the Chinese food in the microwave for far too long — don’t try this at home without saving first! — we get an interesting description when we look at it again.

>x chinese food

This is a carton of radioactive Szechuan shrimp. Lovely red peppers poke out of the sauce.

The association of microwaves with nuclear bombs, and particularly the now ubiquitous slang to “nuke” one’s food, would appear to be another MITism that has entered the larger culture. Janice remembers hearing the slang during her time there as an undergraduate in the early 1980s, yet online etymologies claim its first documented use dates from 1987, the very year of The Lurking Horror.

At this point I’ll leave you to do something for the hacker and get something from him in return. Once you’ve taken care of that, let’s head for the elevator to begin to explore the rest of the campus.

>s

Elevator

This is a battered, rather dirty elevator. The fake wood walls are scratched and marred with graffiti. The elevator doors are open. To the right of the doors is an area with floor buttons (B and 1 through 3), an open button, a close button, a stop switch, and an alarm button. Below these is an access panel which is closed.

>x graffiti

"'God is dead' --Nietzsche

'Nietzsche is dead' --God"

The elevator doors slide closed.

>g

"Tech is hell."

>g

"I.H.T.F.P."

The nickname of simply “Tech” in reference to MIT is like many traditions there in that it goes back one hell of a long way. Between its founding in Boston in 1861 and its move across the Charles River to Cambridge in 1916, MIT was more commonly referred to as “Boston Tech” than by its official name. In student parlance part of the nickname stuck around even after the move.

“I.H.T.F.P.” is another phrase with which all too many students are casually familiar. Sometimes described as the university’s unofficial motto, it stands for “I hate this fucking place.” Much as so many come to cherish their time at the university, the graffiti highlights a fact that can often get lost amid descriptions of all of the assorted traditions and tomfoolery (often one and the same) that go on at MIT: the fact that it is indeed, as Infocom’s GUE Tech brochure says, “a high-pressure school.” In fact, it’s the most demanding STEM university in the world. For decades there have been dark jokes among the student population about suicide, along with suspicions that the actual suicide rate is not being accurately reported. How’s that for a spot of horror?

Let’s take the elevator down a floor — be sure to check out that access panel first! — and then head out to the street.

>n

You enter the freezing, biting cold of the blizzard.

Smith Street

Smith Street runs east and west along the north side of the main campus area. At the moment, it is an arctic wasteland of howling wind and drifting snow. On the other side of the street, barely visible, are the lidless eyes of streetlights. The street hasn't been plowed, or if it has been, it did no good.

Massachusetts winters can be every bit as brutal as the one described here; they’re as much a fixture of life at MIT as any other tradition. As for the streets themselves: MIT’s Vassar Street is slyly replaced here by Smith Street, Smith being another of the “Seven Sisters” of prestigious, historically female liberal-arts colleges. Just down Smith Street to the east is an innocuous-looking “temporary building” with one hell of a story to tell.

>s

You push your way into the comparative warmth of a laboratory.

It is pitch black.

>turn on flashlight

The flashlight clicks on.

Temporary Lab

This is a laboratory of some sort. It takes up most of the building on this level, all the interior walls having been knocked down. (One reason these temporary buildings are still here is their flexibility: no one cares if they get more or less destroyed.) A stairway leads down, and a door leads north.

There is a metal flask here.

>get flask

Taken.

>d

Temporary Basement

During the Second World War, some temporary buildings were built to house war-related research. Naturally, these buildings, though flimsy and ugly, are still around. This is the basement of one of them. The basement extends west, a stairway leads up, and a large passage is to the east.

This rattletrap of a structure corresponds to the real MIT’s now long-gone Building 20, one of the most storied places on the campus. It was built quickly and cheaply in 1943 to house vital wartime research into radar. The expectation was that it would be destroyed as soon as the war was over. But, with postwar attendance booming thanks to the G.I. Bill and research space at a premium, no one quite got around to it for more than fifty years. Building 20 was a famously ramshackle place, showing ample evidence of its cheap and rushed construction. Walls were made of exposed plywood; ceilings were hidden above a tangle of pipes and wiring; floors were treacherously uneven; the roof leaked; windows never really fit right, and had a disconcerting habit of falling off entirely; the whole structure creaked alarmingly in the winds that blew right through its interior. It was sweltering in the summer and freezing in the winter, and coated with a litigator’s wet dream worth of asbestos and lead-based paint. Yet the people who worked inside it loved the place, dubbing it their “plywood palace.”

Building 20 would be of great historical importance were it only for the World War II research that went on there. Research into radar was funded almost as lavishly as the Manhattan Project, and was even more important for actually winning the war; “Radar won the war, and the atom bomb ended it,” goes the old saying. Much of that war-winning effort was centered right here.

But that was only the beginning. In later years countless other groups moved in and out of Building 20, doing important research into physics (an early atomic accelerator was built here, as was the world’s first atomic clock); linguistics (Noam Chomsky worked here for many years); neurology (Jerome Lettvin’s pioneering experiments on the relationship between the eyes and brains of frogs took place here); acoustics (Amar Bose, founder of Bose Corporation, worked here). Researchers loved Building 20 precisely because it was such a dump. They could feel free to drill holes in walls for cables — or knock them down entirely for that matter — and do plenty of other things that would require reams of paperwork and several safety reviews and months of bureaucratic wrangling to do anywhere else.

Most fascinating of all for our purposes, Building 20 is also Ground Zero for hacker culture. During the late 1950s it was the home of the Tech Model Railroad Club, about half of which consisted of typical train enthusiasts and half of which were there for the intrinsic interest of the plumbing, so to speak: all those wires and switches and diodes found underneath the big tables that supported the track layout. Much of the vocabulary they developed remains with us to the present day: a bad design was “losing”; a broken piece was “munged” (“mashed until no good”); unnecessary extra pieces were “cruft”; and, yes, a “hack” was a particularly clever technical feat, and “hacking” was… you get the idea. This diction and, even more importantly, the way of thinking behind it was transferred into a new field when a former TMRC member and current MIT professor invited some members to have a go at a new toy: a home-built something called the TX-0, one of the first transistorized computers and one of the first designed to be programmed and operated interactively rather than functioning as essentially a huge static calculating and collating machine. Several of the men who had helped design it went on to form Digital Equipment Corporation, donating the very first complete prototype computer they ever made, of their debut PDP-1 model, to MIT for more TMRC alumni to swarm over. Thus cemented, the links among DEC, MIT, and hacker culture persisted through the heyday of the original PDP-10 Zork and on into the 1980s. Infocom’s own aging PDP-10, on which The Lurking Horror itself was written, was just one more testament to the durability of those links.

Building 20 was demolished at last in 1999 to make room for the Stata Center, a massive slab of postmodern architecture, sort of a 21st-century Sagrada Família, that was opened in 2004. In the tradition of its predecessor, the Stata Center has been plagued by leaks, plumbing problems, and structural failures since its opening. Perhaps a ghost or two lives on?

The Lurking Horror departs from reality in giving its version of Building 20 a basement and an underground connection to the central buildings of the campus. In the game’s defense, visitors to Building 20 often remarked that the ground floor was so dank and dark that it felt like a basement. For reasons that have been lost to history, MIT chose to label that ground floor, normally Floor 1 in the university’s nomenclature, as Floor 0, as if it was indeed a basement. Just after the building was demolished in 1999, a student hack stuck an elevator in the midst of the rubble leading to a “previously hidden” subbasement stretching five stories below ground-level, presumably home of some top-secret and quite possibly nefarious government research. Aliens, anyone? These days the joke is that Building 20 is actually still standing, but hidden behind an invisibility field — perhaps a gift of those same aliens?

At some point you’ll meet an urchin skulking about down here in the basement.

>x urchin

This is an urchin. He's a youngish teenager wearing a ski hat, running shoes, and a bulky, suspiciously bumpy, threadbare parka. He's jumpy, and looks suspiciously at you.

I’m going to spoil things just to the extent of telling you that what he’s carrying beneath his parka is a pair of bolt cutters. It appears that this fellow is a bicycle thief, a consistent plague on the MIT campus since time immemorial. Kids like this one who hang about, usually for shady purposes, are indeed known as “urchins” in student parlance. When their crimes get particularly blatant, “urchin alerts” are sent out to the affected areas to warn students and faculty to keep a close eye on their valuables.

At this point you’ll likely want to do something about those old pallets off to the east and then do a bit of exploring in that direction. When you’re ready, let’s go all the way west and down the stairs to the subbasement, and then squeeze northwest through the crack.

Tomb

This is a tiny, narrow, ill-fitting room. It appears to have been a left over space from the joining of two preexisting buildings. It is roughly coffin shaped. The walls are covered by decades of overlaid graffiti, but there is one which is painted in huge fluorescent letters that were apparently impossible for later artists to completely deface. On the floor is a rusty access hatch locked with a huge padlock.

>read graffiti

It reads "The Tomb of the Unknown Tool."

The Tomb of the Unknown Tool is a real place at MIT, and another semi-legendary one at that. Legend has it that long ago there was an MIT student who was trying to study — to “tool” in student parlance; similarly, the noun “tool” is a dismissive term for a good, conventionally diligent student — but couldn’t because of all the loud parties in his dorm. So he found a little cubbyhole far underground, filled with heating and air-conditioning pipes and ducts, and made it his home, eating there, sleeping there, and most of all tooling there in peace. The unknown tool himself was long gone even by the time Lebling first arrived at MIT in the late 1960s, but his legend lives on. Always an early destination of aspiring roof-and-tunnel hackers, the real Tomb is situated in roughly the same location as the one that’s found in the game. And its walls are indeed covered with graffiti left behind by the many who have visited.

The Lurking Horror is actually not the first game in which Lebling referred to the Tomb of the Unknown Tool. The original PDP-10 Zork includes a “Tomb of the Unknown Implementors,” with graffiti of its own that says to “Feel Free!”

In that spirit, feel free to go through the hatch here and explore even deeper. When you’re ready, let’s go southeast from the Tomb, up twice, south to the Infinite Corridor (which we’ll come back to in just a moment), and finally west into the great outdoors again.

Mass. Ave.

This is the main entrance to the campus buildings. Blinding snow obscures the stately Grecian columns and rounded dome to the east. You can barely make out the inscription on the pediment (which reads "George Vnderwood Edwards, Fovnder; P. David Lebling, Architect"). West across Massachusetts Avenue are other buildings, but you can't see them.

We’re now standing at the front door to MIT. The address of the imposing building that stands here, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, is the official address of the institution as a whole. Erected in 1939, the Rogers Building (Building 7) gets its name from that of MIT’s founder, William Barton Rogers. It also bears his name on its pediment, although no “Architect” is credited.

Massachusetts Avenue is the only MIT street name that remains unaltered in the game. That it shows up in abbreviated form as the location name is not accidental; it’s universally pronounced “Mass. Ave” by students.

But it’s cold out here, no? Let’s go back inside.

Infinite Corridor

The so-called infinite corridor runs from east to west in the main campus building. This is the west end. Side corridors lead north and south, and a set of doors leads west into the howling blizzard.

There is a plastic container here.

There is a largish machine being operated down the hall to the east.

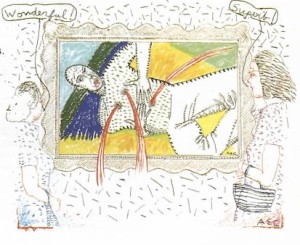

The Infinite Corridor during MIThenge.

The Infinite Corridor is another source of much MIT lore. It’s the longest university corridor in the world, stretching east from the Rogers Building under the Great Dome and across the pre-World War II heart of the campus to Building 8 — a distance of 825 feet. One of the most celebrated events at MIT is the so-called “MIThenge,” when twice per year the sun shines just perfectly into the corridor to illuminate it down its entire length. If all that wasn’t enough to ensure the Infinite Corridor’s notoriety, many fondly remembered hacks have also taken place here. A popular theme for decades had been to deck out the Corridor like a highway of one sort or another, often complete with lane markings, road signs, and billboards.

>get container

Taken.

>x container

It's a plain plastic container with something written on it. The plastic container is closed.

>read container

"Frobozz Magic Floor Wax (and Dessert Topping)"

The joke above isn’t quite original, and for once it’s not an MIT-specific in-joke. It harks back to a classic skit from the very first season of Saturday Night Live, in which Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd, and Chevy Chase bond over Shimmer, a floor wax and dessert topping. One can imagine Lebling laughing at this around the same time he was working on Maze War at MIT, the world’s first networked multiplayer first-person shooter which he helped create almost two decades before Doom.

Moving down the Infinite Corridor to the east, we come upon a maintenance man.

A maintenance man is here, riding a floor waxer.

The maintenance man’s presence is a very subtle shade of in-joke. MIT’s housekeeping and custodial staff tended to do their work in the middle of the night, when the campus was largely deserted. Hackers like Lebling and company, however, tended to keep exactly the same sorts of odd hours, another tradition that stretched all the way back to the days of the TX-0; “legitimate” users always kept that machine booked during the day, leaving it available only during the nighttime for the likes of the Tech Model Railroad Club. Hackers were often the only students that the janitors and housekeepers ever actually encountered, and some surprising and kind of sweet friendships formed thanks to the forced proximity between these very different walks of life.

This particular maintenance man, however, definitely doesn’t want to be our friend. I recommend that you deal with him now, if you can. If you’ve been dutifully gathering up the stuff you come across, you should have everything you need. I’m going to go south from the center of the Infinite Corridor, but you don’t want to follow me to where I go next unless you save first because the door will lock behind us, and for once our master key won’t open it (a rather pointless bit of cruelty on the whole, although to his credit Lebling does warn us).

Great Court

In the spring and summer, this cheery green court is a haven from classwork. Right now, the majestic buildings of the main campus are almost invisible in the howling blizzard. A locked door bars your way to the north.

We’re standing now at the center of the original 1916 Cambridge campus, designed by architect William Welles Bosworth. This court was also known as the Great Court at the real MIT until 1974, when it was renamed Killian Court after former MIT president James Rhyne Killian. Despite the rechristening, the old name stuck around for a long time, especially among folks like Lebling who were here before the change. MIT architecture in general is noted for its complete disharmony, a riot of mismatched buildings that seems to include at least one example of every American architectural school of the last century along with plenty of bland beige buildings with no discernible style at all. This original part of the campus, however, is coolly neoclassical, the lushly manicured central court bordered by trees, the buildings on either side forming arms that seem to bid the world to enter, much like St. Peter’s Basilica. It’s here, the only really bucolic place on campus, that commencement ceremonies are held every year.

Back inside — and assuming you’ve dealt with the janitor — let’s go up, up, up, all the way to the very tiptop of the Great Dome. You’ll need to solve a puzzle or two to manage it, but I’m sure you’re up to it.

You scramble up the icy surface of the dome, almost slipping a few times, but finally you make it to the top.

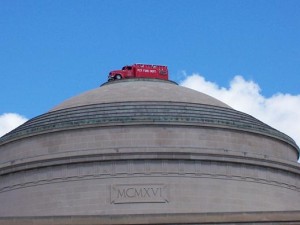

On the Great Dome

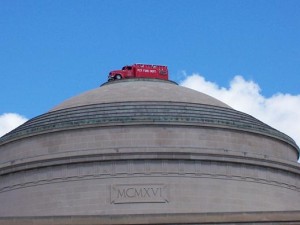

This is the very top of the Great Dome, a favorite place for Tech fraternities to install cows, Volkswagen Beetles, giant birthday candles, and other bizarre objects. The top is flat, round, and about five feet in diameter. It's very windy, which has kept the snow from accumulating here. The only way off is down.

In the exact center of the flat area is a bronze plug.

Bitter, bone-cracking cold assaults you continuously. The temperature and the blizzard conditions are both horrible.

Despite interlopers like the Stata Center, the Great Dome, referred to affectionately by students as “the center of the universe,” still stands as the most enduring architectural image of MIT. As the game has made evident, just getting up here at all is a major feat of roof-and-tunnel hacking. For the even more ambitious, it’s also the ultimate location for an MIT hack (in the practical-joking sense, that is). Over the years a police cruiser, an Apollo Lunar Module, a Doctor Who phone box, a self-propelled solar-powered subway car, and a living cow have all appeared up here. The Great Dome has been coated with tin foil and has been turned into R2-D2, Tolkien’s One Ring, a giant cupcake, and a Halloween pumpkin, while the lights that illuminate it at night seem to change color constantly to celebrate one occasion or another. One of the earliest and most legendary of the Great Dome hacks occurred in 1959, when a complete working Volkswagen was torn down, carted up to the Dome, and reassembled there in the course of one long night.

A fire engine perches on the Great Dome.

After you’ve investigated thoroughly up here, let’s get back to ground level and go east to the end of the Infinite Corridor. Going north, we pass through the Nutrition Department.

>n

Fruits and Nuts

This is the central corridor of the Nutrition Building. The main building is south, and a stairway leads down.

The MIT Nutrition Department is indeed referred to with a certain contempt as “Fruits and Nuts” by hackers. (Think back to those four basic food groups…)

Going down the stairs here and then southeast takes us to the basement of the Brown Building. Let’s go up to the lobby and outside again.

Brown Building

This is the lobby of the Brown Building, an eighteen-story skyscraper which houses the Meteorology Department and other outposts of the Earth Sciences. The elevator is out of order, but a long stairway leads up to the roof, and another leads down to the basement. A revolving door leads out into the night.

>exit

You enter the freezing, biting cold of the blizzard.

Small Courtyard

This courtyard is a triumph of modern architecture. It is spare, cold, angular, overwhelming in size, and bears a striking resemblance to a wind tunnel whenever the breeze picks up. Right now this is true of the whole campus, though. A huge mass lurks nearby, and an almost featureless skyscraper is to the north.

>x mass

You see nothing special about it.

Bitter, bone-cracking cold assaults you continuously. The temperature and the blizzard conditions are both horrible.

GUE’s Brown Building stands in for the real MIT’s Green Building, which is even taller, a full 21 stories and almost 300 feet. Built in 1964, it’s yet another architectural outlier in this campus full of outliers, not only the only structure of its kind at MIT but also the only one in Cambridge; no other building there comes close to its height. As such a blatant violation of MIT and Cambridge’s normal philosophy of “horizontal continuity,” its construction was greeted with considerable controversy, not to mention outrageous rumors about the methods used to circumvent Cambridge’s normal building laws. The first tenants found that its height and proximity to the rest of the campus created a sort of artificial wind tunnel, the breeze coming off the Charles River getting so amplified that on blustery days it was impossible to even open the doors. Luckily, there were also connecting tunnels (like the one we just came through) leading to other buildings, preventing a change in the weather from trapping people inside. The original doors were eventually replaced with revolving doors. These largely alleviated one problem, but, as the description from the game relates, the courtyard remains a remarkably unpleasant place, particularly in winter.

Not really one of MIT’s more beloved buildings for all of these reasons, the Green Building’s height and general prominence on campus have nevertheless made it a target for hacks to rival the popularity of the Great Dome. For almost as long as the Green Building has existed, it’s been a Halloween tradition to throw dozens or hundreds of pumpkins down from its roof. In 1974, a professor and some of his students launched a concerted effort to operate the world’s largest yo-yo from the roof of the building, but for once this ambitious hack never quite worked out. Since the advent of cheap LED lighting, the Green Building has taken on a new role as a massive billboard telling the world what MIT students are thinking about at any given time. In 2012, students made the national news by turning it into the world’s biggest game of Tetris, inviting passersby to have a go for all of Cambridge to see. (No pressure!)

The undefined “huge mass” that Lebling describes is a sly dig at another polarizing structure that sits before the Green Building, Alexander Calder’s monumental slab of modernist sculpture The Big Sail. When it was erected just a year after the Green Building itself, conventional wisdom had it that its primary purpose was to alleviate the wind-tunnel effect. But campus officials insisted that, no, this… whatever it is… exists only for aesthetic purposes. Oh, well… what better spot for a Big Sail than a wind tunnel? It does look a bit like one of Lovecraft’s horrid winged creatures might, at least if you squint just right, so I suppose it makes a good fit for the game.

The Green Building really does house, among other departments, many of MIT’s Meteorology and Earth Science facilities. In that respect its controversial height has been a blessing: the roof supports much meteorological and radio equipment used in various experiments. Let’s head inside and up there now.

Top Floor

This is the top of the stairway. A door leads out to the roof here, and you can hear the wind blowing beyond. There is a sign on the door.

>read sign

It says "NO ADMITTANCE!" In smaller, hand-written letters below, it says "This means you!" and below that in different handwriting, it says "Who, me?"

>unlock door with key

The door is now unlocked.

>open door

You push the door open, revealing a windswept, snow-covered roof. Frigid wind whips snow into your face.

When Dave Lebling was at MIT, he used to make his way out to the roof of the Green Building through a fire door that was much like this one. Its sign read, “Positively No Admittance, Opening Door Sounds Alarm.” The first student to trepidatiously push it open found that it did no such thing, and thus was yet another interesting space opened for exploration.

Let’s head onward, shall we?

>exit

You enter the freezing, biting cold of the blizzard.

Skyscraper Roof

A low parapet surrounds a small roof here. The air conditioning cooling tower and the small protrusion containing the stairs are dwarfed by a semitransparent dome which towers above you. The blowing snow obscures all detail of the city across the river to the south.

>x dome

The dome is large and semitransparent. It's made of some sort of milky-colored plastic. It dominates the roof. You can climb up to the entrance via a short ladder.

Bitter, bone-cracking cold assaults you continuously. The temperature and the blizzard conditions are both horrible.

>u

You push your way into the welcoming warmth inside.

Inside Dome

You are inside a large domed area. The dome contains equipment that makes it clear it is a weather observation station. For some reason, it also contains a small peach tree. Wind whistles outside, and snow blasts against the semitransparent material of the dome.

Something smashes against the glass of the dome! You turn and see a dark shape clinging to the outside of the structure.

As you can see from the picture of the real Green Building, its roof supports a large dome much like this one, full of meteorological equipment, albeit one that is opaque rather than transparent. Lebling insists, however, that there was once another dome that was semi-transparent like this one. Further, he insists that there really was a tree inside said dome, although he’s not sure that it was actually a peach tree. No one he asked seemed to have any idea who put it there or what its purpose was. Mysteries like this aren’t particularly unusual at MIT. Incomprehensible equipment from one esoteric research project or another positively litters the campus, often stashed in the very out-of-the-way corners that make roof-and-tunnel hacking so enticing.

Given that, why not a burgeoning temple to an eldritch god as well? Let’s head for the last stop on our tour, The Department of Alchemy — as soon as you’ve investigated the dome thoroughly and dealt with that inconvenient monster, that is. Afterward, you want to go back down to the basement, up into Building 8, and south from the eastern end of the Infinite Corridor.

Chemistry Building

This corridor is lined with closed, dark offices. At the south end of the corridor is a door with a light shining behind it. There is something written on the door.

>read door

Painted on the door, in calligraphy indistinguishable from any other door at Tech, is the phrase "Department of Alchemy." You always used to wonder what was behind that door.

As was the case with the Tomb of the Unknown Tool, you may be surprised to learn that the Department of Alchemy is a real place at MIT — or, at any rate, that this Department of Alchemy door is real. Like in the game, it’s inside the Department of Chemistry, an example of a hack dating back many decades that was just too good to ever unhack. And, again like in the game, the real door conceals a laboratory. But the people inside do not attempt to summon blasphemous creations from the Beyond, at least as far as anyone knows.

Inside the door you’ll find a tricky — and very dangerous! — sequence awaiting you. You definitely want to save before this one, as you’re probably about to get sacrificed a few times before you get it all sorted. When you do (get it all sorted, that is), you’ll have a class ring at your disposal.

>x hyrax

The G.U.E. Tech class ring is a gold ring depicting a hyrax eating a twig. Such rings are familiarly known as "brass hyraxes."

The actual MIT class ring shows, for some reason, an alleged beaver eating a twig. But it looks more like a rat, and is thus commonly referred to as a “brass rat.”

And at this point we’ve largely seen the sights in The Lurking Horror that relate back to MIT. But there’s still lots of puzzles to solve and a blasphemous evil to defeat, so I’ll leave you to it. Remember the four basic food groups — particularly the first — when you get tired, and remember that Hollywood Hijinx isn’t the only Infocom game that evinces a certain fascination with elevators. I hope you’ve enjoyed this little tour. If you have, I’m pretty sure there are a couple of virtual tip jars around here if you scroll to the top and look to the right. Good luck!

(If you’d like all of these annotations and more in a succinct form, feel free to download the gloss of the game that Janice Eisen so kindly prepared for me. This document was the basis for much of what I’ve written above.)