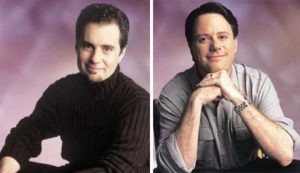

Louis Castle first became friends with Brett Sperry in 1982, when the two were barely out of high school. Castle was selling Apple computers at the time at a little store in his native Las Vegas, and Sperry asked him to print out a file for him. “I owned a printer, so I invited him over,” remembers Castle, “and he looked at some animation and programming I was working on.”

They found they had a lot in common. They were both Apple II fanatics, both talented programmers, and both go-getters accustomed to going above and beyond what was expected of them. Through Castle’s contacts at the store — the home-computer industry was quite a small place back then — they found work as contract programmers, porters who moved software from one platform to another. It wasn’t the most glamorous job in the industry, but, at a time when the PC marketplace was fragmented into close to a dozen incompatible platforms, it was certainly a vital one. Sperry and Castle eventually came to specialize in the non-trivial feat of moving slick action games such as Dragonfire and Impossible Mission from the Commodore 64 to the far less audiovisually capable Apple II without sacrificing all of their original appeal.

In March of 1985, they decided to give up working as independent contractors and form a real company, which they named Westwood Associates. The “Westwood” came from the trendy neighborhood of Los Angeles, around the UCLA campus, where they liked to hang out when they drove down from Las Vegas of a weekend. “We chose Westwood as the company name,” says Castle, “to capture some of the feeling of youthful energy and Hollywood business.” The “Associates,” meanwhile, was nicely non-specific, meaning they could easily pivot into other kinds of software development if the games work should dry up for some reason. (The company would become known as Westwood Studios in 1992, by which time it would be pretty clear that no such pivot would be necessary.)

The story of Westwood’s very first project is something of a harbinger of their future. Epyx hired them to port the hoary old classic Temple of Apshai to the sexy new Apple Macintosh, and Sperry and Castle got a bit carried away. They converted the game from a cerebral turn-based CRPG to a frenetic real-time action-adventure, only to be greeted with howls of protest from their employers. “Epyx felt,” remembers Castle with no small sense of irony, “that gamers would not want to make complicated tactical and strategic decisions under pressure.” More sensibly, Epyx noted that Westwood had delivered not so much a port as a different game entirely, one they couldn’t possibly sell as representing the same experience as the original. So, they had to begrudgingly switch it back to turn-based.

This blind alley really does have much to tell us about Westwood’s personality. Asked many years later what common thread binds together their dizzily eclectic catalog of games, Louis Castle hit upon real-time gameplay as the one reasonable answer. This love of immediacy would translate, as we’ll soon see, into the invention of a whole new genre known as real-time strategy, which would become one of the most popular of them all by the end of the 1990s.

But first, there were more games to be ported. Having cut their teeth making Commodore 64 games work within the constraints of the Apple II, they now found themselves moving them in the other direction: “up-porting” Commodore 64 hits like Super Cycle and California Games to the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga. Up-porting was in its way as difficult as down-porting; owners of those more expensive 16-bit machines expected their capabilities to be used to good effect, even by games that had originated on more humble platforms, and complained loudly at straight, vanilla ports that still looked like they were running on an 8-bit computer. Westwood became one of the best in the industry at a very tricky task, not so much porting their source games in any conventional sense as remaking them, with dramatically enhanced graphics and sound. They acquired a reputation for technical excellence, particularly when it came to their compression systems, which allowed them to pack their impressive audiovisuals into very little space and stream them in quickly from disk. And they made good use of the fact that the Atari ST and Amiga were both built around the same Motorola 68000 CPU by developing a library for the Amiga which translated calls to the ST’s operating system into their Amiga equivalents on the fly; thus they could program a game for the ST and get the same code running on the Amiga with very few changes. If you wanted an 8-to-16-bit port done efficiently and well, you knew you could count on Westwood.

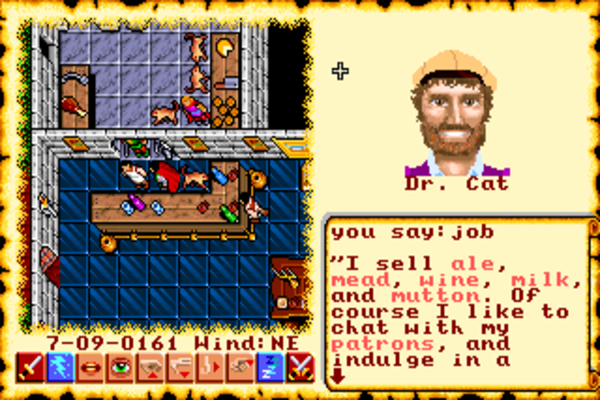

Although they worked with quite a number of publishers, Westwood cultivated a particularly close relationship with SSI, a publisher of hardcore wargames who badly needed whatever pizazz Sperry and Castle’s flashier aesthetic could provide. When SSI wanted to convince TSR to give them the hugely coveted Dungeons & Dragons license in 1987, they hired Westwood to create some of the graphics demos for their presentation. The pitch worked; staid little SSI shocked the industry by snatching the license right out from under the noses of heavier hitters like Electronic Arts. Westwood remained SSI’s most trusted partner thereafter. They ported the “Gold Box” line of Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs to the Atari ST and Amiga with their usual flair, adding mouse support and improving the graphics, resulting in what many fans consider to be the best versions of all.

Unfortunately, Westwood’s technical excellence wasn’t always paired with equally good design sense when they occasionally got a chance to make an original game of their own. Early efforts like Mars Saga, Mines of Titan, Questron II, and BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception all have a lot of ideas that aren’t fully worked through and never quite gel, along with third acts that fairly reek of, “We’re out of time and money, and now we just have to get ‘er done.” Ditto the first two original games they did for SSI under the Dungeons & Dragons license: the odd California Games/Gold Box mashup Hillsfar and the even odder dragon flight simulator Dragon Strike.

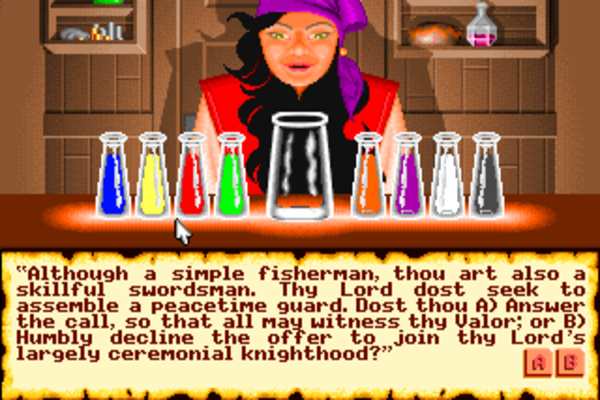

Still, Brett Sperry and Louis Castle were two very ambitious young men, and neither was willing to settle for the anonymous life of a strict porting house. Nor did such a life make good business sense: with the North American market at least slowly coalescing around MS-DOS machines, it looked like porting houses might soon have no reason to exist. The big chance came when Sperry and Castle convinced SSI to let them make a full-fledged Dungeons & Dragons CRPG of their own — albeit one that would be very different from the slow-paced, turn-based Gold Box line. Westwood’s take on the concept would run in — you guessed it — real time, borrowing much from FTL’s Dungeon Master, one of the biggest sensations of the late 1980s on the Atari ST and Amiga. The result was Eye of the Beholder.

At the time of the game’s release in February of 1991, FTL had yet to publish an MS-DOS port of Dungeon Master. Eye of the Beholder was thus the first real-time dungeon crawl worth its salt to become available on North America’s computer-gaming platform of choice, and this fact, combined with the Dungeons & Dragons logo on the box, yielded sales of 130,000 copies in the United States alone — a sales figure far greater than that of any previous original Westwood game, greater even than all but the first two of SSI’s flagship Gold Box line. The era of Westwood as primarily a porting house had passed.

Over at Virgin Games, the indefatigable Martin Alper, still looking to make a splash in the American market, liked what he saw in Westwood, this hot American developer who clearly knew how to make the sorts of games Americans wanted to buy. And yet they were also long-established experts at getting the most out of the Amiga, Europe’s biggest gaming computer; Westwood would do their own port of Eye of the Beholder to the Amiga, in which form it would sell in considerable numbers in Europe as well. Such a skill set made the little Las Vegas studio immensely attractive to this executive of Virgin, a company of truly global reach and vision.

Alper knew as soon as he saw Eye of the Beholder that he wanted to make Westwood a permanent part of the Virgin empire, but, not wanting to spook his target, he approached them initially only to ask them to develop a game for him. As far as Alper or anyone else outside Virgin’s French subsidiary knew at this point, the Cryo Dune game was dead. But Alper hadn’t gone to all the trouble of securing the license not to use it. In April of 1991 — just one month before the departure of Jean-Martial Lefranc from Virgin Loisirs, combined with a routine audit, would bring the French Dune conspiracy to light — Alper signed Westwood to make a Dune game of their own. It wasn’t hard to convince them to take it on; it turned out that Dune was Brett Sperry’s favorite novel of all time.

Even better, Westwood, perhaps influenced by their association with the turn-based wargame mavens at SSI, had already been playing around with ideas for a real-time (of course!) game of military conflict. “It was an intellectual puzzle for me,” says Sperry. “How can we take this really small wargame category, bring in some fresh ideas, and make it a fun game that more gamers can play?” The theme was originally to be fantasy. But, says Louis Castle, “when Virgin offered up the Dune license, that sealed our fate and pulled us away from a fantasy theme.”

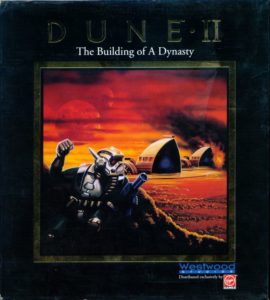

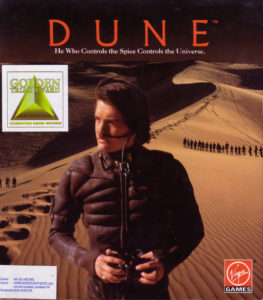

Several months later, after Martin Alper reluctantly concluded that Cryo’s Dune had already cost too much money and had too much potential of its own to cancel, he found himself with quite a situation on his hands. Westwood’s Dune hadn’t been in development anywhere near as long as Cryo’s, but he was already loving what he had seen of it, and was equally unwilling to cancel that project. In an industry where the average game frankly wasn’t very good at all, having two potentially great ones might not seem like much of a problem. For Virgin’s marketers, however, it was a nightmare. Their solution, which pleased neither Cryo nor Westwood much at all, was to bill the latter’s game as a sequel to the former’s, naming it Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty.

Westwood especially had good reason to feel disgruntled. They were understandably concerned that saddling their fresh, innovative new game with the label of sequel would cause it to be overlooked. The fact was, the sequel billing made no sense whatsoever, no matter how you looked at it. While both games were, in whole or in part, strategy games that ran in real time, their personalities were otherwise about as different as it was possible for two games to be. By no means could one imagine a fan of Cryo’s plot-heavy, literary take on Dune automatically embracing Westwood’s action-heavy, militaristic effort. Nor did the one game follow on from the other in the sense of plot chronology; both games depict the very same events from the novel, albeit with radically different sensibilities.

The press too was shocked to learn that a sequel to Cryo’s Dune was due to be released the very same year as its predecessor. “This has got to be a new world record for the fastest ever followup,” wrote the British gaming magazine The One a few weeks after the first Dune‘s release. “Unlike the more adventure-based original, Dune II is expected to be more of a managerial experience comparable to (if anything) the likes of SimCity, as the two warring houses of Atreides and Harkonnen attempt to mine as much spice as possible and blow each other up at the same time.”

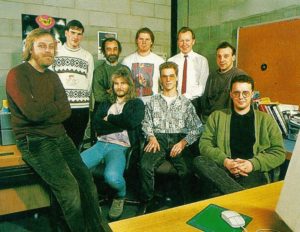

The Westwood Studios team who made Dune II. On the front row are Ren Olsen and Dwight Okahara; on the middle row are Judith Peterson, Joe Bostic, Donna Bundy, and Aaron Powell; on the back row are Lisa Ballan and Scott Bowen. Of this group, Bostic and Powell were the game’s official designers, and thus probably deserve the most credit for inventing the genre of real-time strategy. Westwood’s co-founder Brett Sperry also played a critical — perhaps the critical — conceptual role.

It was, on the whole, about as good a description of Dune II as any that appeared in print at the time. Not only was the new game dramatically different from its predecessor, but it wasn’t quite like anything at all which anyone had ever seen before, and coming to grips with it wasn’t easy. Legend has it that Brett Sperry started describing Dune II in shorthand as “real-time strategy” very early on, thus providing a new genre with its name. If so, though, Virgin’s marketers didn’t get the memo. They would struggle mightily to describe the game, and what they ended up with took unwieldiness to new heights: a “strategy-based resource-management simulation with a heavy real-time combat element.” Whew! “Real-time strategy” does have a better ring to it, doesn’t it?

These issues of early taxonomy, if you will, are made intensely interesting by Dune II‘s acknowledged status as the real-time-strategy urtext. That is to say that gaming histories generally claim, correctly on the whole in my opinion, that it was the first real-time strategy game ever.

Yet we do need to be careful with our semantics here. There were actually hundreds of computerized strategy games prior to Dune II which happened to be played in real time, not least among them Cryo’s Dune. The neologism of “real-time strategy” (“RTS”) — like, say, those of “interactive fiction” or even “CRPG” — has a specific meaning separate from the meanings of the individual words which comprise it. It has come to denote a very specific type of game — a game that, yes, runs in real time, but also one where players start with a largely blank slate, gather resources, and use them to build a variety of structures. These structures can in turn build military units who can carry out simple orders of the “attack there” or “defend this” stripe autonomously. The whole game plays on an accelerated time scale which yields bursts if not sustained plateaus of activity as frantic as any action game. This combination of qualities is what Westwood invented, not the abstract notion of a strategy game played in real time rather than turns.

Of course, all inventions stand on the shoulders of those that came before, and RTS is no exception. It can be challenging to trace the bits and pieces which would gel together to become Dune II only because there are so darn many of them.

The earliest strategy game to replace turns with real time may have been Utopia, an abstract two-player game of global conquest designed and programmed by Don Daglow for the Intellivision console in 1982. The same year, Dan Bunten’s [1]Dan Bunten died in 1998 as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. science-fiction-themed Cytron Masters and Chris Crawford’s Roman-themed Legionnaire became the first computer-based strategy games to discard the comfortable round of turns for something more stressful and exciting. Two years later, Brøderbund’s very successful The Ancient Art of War exposed the approach to more players than ever before.

In 1989, journalists started talking about a new category of “god game” in the wake of Will Wright’s SimCity and Peter Molyneux’s Populous. The name derived from the way that these games cast you as a god able to control your people only indirectly, by altering their city’s infrastructure in SimCity or manipulating the terrain around them in Populous. This control was accomplished in real time. While, as we’ve seen, this in itself was hardly a new development, the other innovations of these landmark games were as important to the eventual RTS genre as real time itself. No player can possibly micromanage an army of dozens of units in real time — at least not if the clock is set to run at anything more than a snail’s pace. For the RTS genre as we’ve come to know it to function, units must have a degree of autonomous artificial intelligence, must be able to carry out fairly abstract orders and react to events on the ground in the course of doing so. SimCity and Populous demonstrated for the first time how this could work.

By 1990, then, god games had arrived at a place that already bore many similarities to the RTS games of today. The main things still lacking were resource collecting and building. And even these things had to some extent already been done in non-god games: a 1987 British obscurity called Nether Earth demanded that you build robots in your factory before sending them out against your enemy, although there was no way of building new structures beyond your starting factory. Indeed, even the multiplayer death matches that would come to dominate so much of the RTS genre a generation later had already been pioneered before 1990, perhaps most notably in Dan Bunten’s 1988 game Modem Wars.

But the game most often cited as an example of a true RTS in form and spirit prior to Dune II, if such a thing is claimed to exist at all, is one called Herzog Zwei, created by the Japanese developer Technosoft and first published for the Sega Genesis console in Japan in 1989. And yet Herzog Zwei‘s status as an alternative RTS urtext is, at the very least, debatable.

Players each start the game with a single main base, and an additional nine initially neutral “outposts” are scattered over the map. Players “purchase” units in the form of Transformers-like flying robots, which they then use to try to conquer outposts; controlling more of them yields more revenue, meaning one can buy more units more quickly. Units aren’t completely out of the player’s direct control, as in the case of SimCity and Populous, but are ordered about in a rather general way: stand and fight here, patrol this radius, retreat to this position or outpost. The details are then left to the unit-level artificial intelligence. For this reason alone, perhaps, Herzog Zwei subjectively feels more like an RTS than any game before it. But on the other hand, much that would come to mark the genre is still missing: resource collection is still abstracted away entirely, while there’s only one type of unit available to build, and no structures. In my opinion, Herzog Zwei is best seen as another of the RTS genre’s building blocks rather than an urtext.

The question of whether and to what extent Herzog Zwei influenced Dune II is a difficult one to answer with complete assurance. Brett Sperry and Louis Castle have claimed not to even have been aware of the Japanese game’s existence prior to making theirs. In fact, out of all of the widely acknowledged proto-RTS games I’ve just mentioned, they cite only Populous as a major influence. Their other three stated inspirations make for a rather counter-intuitive trio on the face of it: the 1984 Apple II game Rescue Raiders, a sort of Choplifter mated to a strategic wargame; the 1989 NEC TurboGrafx-16 game Military Madness, an abstract turn-based strategy game; and, later in the development process, Sid Meier’s 1991 masterpiece Civilization (in particular, the tech tree therein).

Muddying these waters, however, is an anecdote from Stephen Clarke-Willson, an executive in Virgin’s American offices during the early 1990s. He says that “everyone at the office was playing Herzog Zwei” circa April of 1991: “I was given the task of figuring out what to do with the Dune license since I’d read the book a number of times. I thought from a gaming point of view the real stress was the battle to control the spice, and that a resource-strategy game would be good.” Clarke-Willson further claims that from the outset “Westwood agreed to make a resource-strategy game based on Dune, and agreed to look at Herzog Zwei for design ideas.” Sperry and Castle, by contrast, describe a far more open-ended agreement that called for them simply to make something interesting out of the license, allowing the specifics of their eventual Dune to arise organically from the work they had already started on their fantasy-themed real-time wargame.

For what it’s worth, neither Sperry nor Castle has a reputation for dishonesty. Quite the opposite, in fact: Westwood throughout its life stood out as a bastion of responsibility and stability in an industry not much known for either. So, whatever the true facts may be, we’re better off ascribing these contradictory testimonies to the vagaries of memories than to disingenuousness. Certainly, regardless of the exact influences that went into it, Dune II has an excellent claim to the title of first RTS in the modern neologism’s sense. This really was the place where everything came together and a new genre was born.

In the novel of Dune, the spice is the key to everything. In the Westwood game, even in the absence of almost everything else that makes the novel memorable, the same thing is true. The spice was, notes Louis Castle, “very adaptable to this harvest, grow, build for war, attack gambit. That’s really how [Dune II] came about.” Thus was set up the gameplay loop that still defines the RTS genre to this day — all stemming from a novel published in 1965.

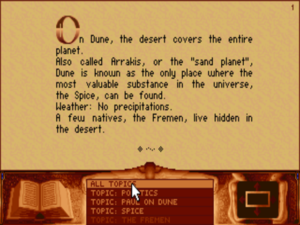

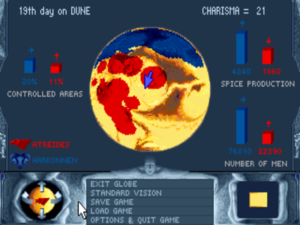

The overarching structure of Dune II is also far more typical of the games of today than those of its peers in the early 1990s. You play a “campaign” consisting of nine scenarios, linked by snippets of narrative, that grow progressively more difficult. There are three of these campaigns to choose from, depicting the war for Arrakis from the standpoint of House Atreides, House Harkonnen, and House Ordos — the last being a cartel of smugglers who don’t appear in the novel at all, having been invented for a non-canonical 1984 source book known as The Dune Encyclopedia. In addition to a different narrative, each faction has a slightly different slate of structures and units at its command.

There’s the suggestion of a more high-level strategic layer joining the scenarios together: between scenarios, the game lets you choose your next target for attack by clicking on a territory on a Risk-like map of the planet. Nothing you do here can change the fixed sequence of scenario goals and opposing enemy forces the game presents, but it does change the terrain on which the subsequent scenario takes place, thus adding a bit more replayability for the true completionists.

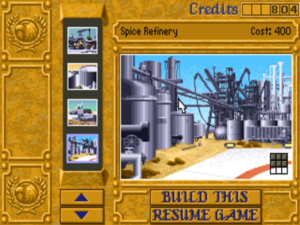

You begin a scenario with a single construction yard, a handful of pre-built units, and a sharply limited initial store of spice, that precious resource from which everything else stems. Fog of war is implemented; in the beginning, you can see only the territory that immediately surrounds your starting encampment. You’ll thus want to send out scouts immediately, to find deposits of spice ripe for harvesting and to learn where the enemy is.

While your scouts go about their business, you’ll want to get an economy of sorts rolling back at home. The construction yard with which you begin can build any structure available in a given scenario, although it’s advisable to first build a “concrete slab” to serve as its foundation atop the shifting sands of Arrakis. The first real structure you’re likely to build is a “wind trap” to provide power to those that follow. Then you’ll want a “spice refinery,” which comes complete with a unit known as a “harvester,” able to collect spice from the surrounding territory and return it to the refinery to become the stuff of subsequent building efforts. Next you’ll probably want an “outpost,” which not only lets you see much farther into the territory around your base without having to deploy units there but is a prerequisite for building any new units at all. After your outpost is in place, building each type of unit requires its own kind of structure, from a “barracks” for light infantry (read: cannon fodder) to a “high tech factory” for the ultimate weapon of airpower. Naturally, more powerful units are more expensive, both in terms of the spice required to build the structures that produce them and that required to build the units themselves afterward.

Your real goal, of course, is to attack and overwhelm the enemy — or, in some later scenarios, enemies — before he or they have the chance to do the same to you. There’s a balancing act here that one could describe as the central dilemma of the game. Just how long do you concentrate on building up your infrastructure and military before you throw your units into battle? Wait too long and the enemy could get overwhelmingly powerful before you cut him down to size; attack too soon and you could be defeated and left exposed to counterattack, having squandered the units you now need for defense. The amount of spice on the map is another stress point. The spice deposits are finite; once they’re gone, they’re gone, and it’s up to whatever units are left to battle it out. Do you stake your claim to that juicy spice deposit just over the horizon right now? Or do you try to eliminate that nearby enemy base first?

If you’ve played any more recent RTS games at all, all of this will sound thoroughly familiar. And, more so than anything else I could write here, it’s this sense of familiarity, clinging as it does to almost every aspect of Dune II, which crystallizes the game’s influence and importance. The only substantial piece of the RTS puzzle that’s entirely missing here is the multiplayer death match; this game is single-player only, lacking the element that for many is the most appealing of all about the RTS genre. Otherwise, though, the difference between this and more modern RTS games is in the details rather than the fundamentals. This anointed first example of an RTS is a remarkably complete example of the breed. All the pieces are here, and all the pieces fit together as we’ve come to expect them to.

So much for hindsight. As for foresight…

Upon its release in the fall of 1992, Dune II was greeted, like its predecessor from Cryo, with positive reviews, but with none of the fanfare one might expect for a game destined to go down in history as such a revolutionary genre-spawner. Computer Gaming World called it merely “a gratifying experience,” while The One was at least a bit more effusive, with the reviewer pronouncing it “one of the most absorbing games I’ve come across.” Yet everyone regarded it as just another fun game at bottom; no one had an inkling that it would in time birth a veritable new gaming subculture. It sold well enough to justify its development, but — very probably thanks in part to its billing as a sequel to a game with a completely different personality, which had itself only been on the market a few months — it never threatened Eye of the Beholder for the crown of Westwood’s biggest hit to date.

Nor did it prompt an immediate flood of games in the same mold, whether from Westwood or anyone else. The next notable example of the budding genre, Blizzard’s Warcraft, wouldn’t appear until late 1994. That title would be roundly mocked by the gaming intelligentsia for its similarities to Dune II — Computer Gaming World would call it “a perfect bit of creative larceny” — but it would sell much, much better, well and truly setting the flame to the RTS torch. To many Warcraft fans, Westwood would seem like the bandwagon jumpers when they belatedly returned to the genre they had invented with 1995’s Command & Conquer.

By the time that happened, Westwood would be a very different place. Just as they were finishing up Dune II, Louis Castle got a call from Richard Branson himself. “Hello, Louis, this is Richard. I’d like to buy your company.”

“I didn’t know it was for sale,” replied Castle.

“In my experience, everything is for sale!”

And, indeed, notwithstanding their unhappiness about Dune II‘s sequel billing, Brett Sperry and Louis Castle sold out to Virgin, with the understanding that their new parent company would stay out of their hair and let them make the games they wanted to make, holding them accountable only on the basis of the sales they generated. Unlike so many merger-and-acquisition horror stories, Westwood would have a wonderful relationship with Virgin and Martin Alper, who provided the investment they needed to thrive in the emerging new era of CD-ROM-based, multimedia-heavy gaming. We’ll doubtless be meeting Sperry, Castle, and Alper again in future articles.

Looked upon from the perspective of today, the two Dune games of 1992 make for an endlessly intriguing pairing, almost like an experiment in psychology or sociology. Not only did two development teams set out to make a game based on the same subject matter, but they each wound up with a strategy game running in real time. And yet the two games could hardly be more different.

In terms of historical importance, there’s no contest between the two Dunes. While Cryo’s Dune had no discernible impact on the course of gaming writ large, Westwood’s is one of the most influential games of the 1990s. A direct line can be traced from it to games played by tens if not hundreds of millions of people all over the world today. “He who controls the spice, controls the universe,” ran the blurb on the front cover of millions of Dune paperbacks and movie posters. Replace “spice” with the resource of any given game’s choice, and the same could be stated as the guiding tenet of the gaming genre Dune birthed.

And yet I’m going to make the perhaps-surprising claim that the less-heralded first Dune is the more enjoyable of the two to play today. Its fusion of narrative and strategy still feels bracing and unique. I’ve never seen another game which plays quite like this one, and I’ve never seen another ludic adaptation that does a better job of capturing the essential themes and moods of its inspiration.

Dune II, by contrast, can hardly be judged under that criterion at all, given that it’s just not much interested in capturing any of the subtleties of Herbert’s novel; it’s content to stop at “he who controls the spice controls the universe.” Judged on its own terms, meanwhile, strictly as a game rather than an adaptation, it’s become the ironic victim of its own immense influence. I noted earlier that all of the pieces of the RTS genre, with the exception only of the multiplayer death match, came together here for the first time, that later games would be left to worry only about the details. Yet it should also be understood that those details are important. The ability to give orders to groups of units; the ability to give more complex orders to units; ways to get around the map more quickly and easily; higher-resolution screens able to show more of the map at one time; a bigger variety of unit types, with greater variance between opposing factions; more varied and interesting scenarios and terrains; user-selectable difficulty levels (Dune II often seems to be stuck on “Brutal”)… later games would do all of this, and so much more besides. Again, these things do matter. Playing Dune II today is like playing your favorite RTS game stripped down to its most basic foundation. For a historian or a student of game design, that’s kind of fascinating. For someone who just wants to play a fun game, it’s harder to justify.

Still, none of this should detract from the creativity and sheer technical chops that went into realizing Dune II in its own time. Most gaming genres require some iteration to work out the kinks and hone the experience. The RTS genre in particular has been so honed by such a plethora of titles, all working within such a sharply demarcated set of genre markers, that Dune II is bound to seem like a blunt instrument indeed when we revisit it today.

So, there you have it: two disparate Dune games, both inspired and worthy, but in dramatically different ways. Dune as evocative storytelling experience or Dune as straightforward interactive ultra-violence? Take your pick. The choice seems appropriate for a novel that’s been pulled back and forth along much the same axis ever since its first publication in 1965. Does it have a claim to the mantle of High Literature or is it “just” an example of a well-crafted genre novel? Take your pick. The same tension shows itself in the troubled history of Dune as movie, in the way it could attract both filmmakers who pursued — or at least believed themselves to be pursuing — a higher artistic calling, like Alejandro Jodorowsky, and purveyors of the massiest of mass-market entertainments, like Arthur P. Jacobs. Dune as art film or Dune as blockbuster? Take your pick — but please, choose one or the other. Dino and Raffaella De Laurentiis, the first people to get an actual Dune film made, tried to split the difference, making it through a mainstream Hollywood studio with a blockbuster-sized budget, but putting all those resources in the hands of a director of art films. As we’ve seen, the result of that collision of sensibilities was unsatisfying to patrons of multiplexes and art-house theaters alike.

In that light, perhaps it really was for the best that Virgin wound up accidentally releasing two Dune games. Cryo’s Dune locked down the artsier side of Dune‘s split media personality, while Westwood’s was just good fun, satisfying the timeless urge of gamers to blow stuff up in entertaining ways. Thanks to a colossal bureaucratic cock-up at Virgin, there is, one might say, a Dune game for every Dune reader. Which one really is “better” is an impossible question to answer in the end. I’ve stated my opinion, but I have no doubt that plenty of you readers could make an equally compelling case in the other direction. So, vive la différence! With all due apologies to Frank Herbert, variety is the real spice of life.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of April 1993, August 1993, and January 1995; Game Developer of June 2001; The One of October 1992, January 1993, and July 1993; Retro Gamer 90; Westwood Studios’s customer newsletter dated Fall 1992. Online sources include Louis Castle’s interview for Soren Johnson’s Designer Notes podcast, “Retro Throwback: Dune 2“ by Cole Machin on CGM, “Build, gather, brawl, repeat: The history of real-time strategy games” by Richard Moss on Ars Technica, “A New Dawn: Westwood Studios 15th Anniversary” by Geoff Keighly with Amer Ajami on GameSpot, and “The Origin of Realtime Strategy Games on the PC” by Stephen Clarke Willson on his blog Random Blts.

Feel free to download Dune II from right here, packaged so as to make it as easy as possible to get running using your chosen platform’s version of DOSBox.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Dan Bunten died in 1998 as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|