Commodore International’s roots are in manufacturing, not computing. They’re used to making and selling all kinds of things, from calculators to watches to office furniture. Computers just happen to be a profitable sideline they stumbled into. Commodore International isn’t really a computer company; they’re a company that happens to make computers. They have no grand vision of computing in the future; Commodore International merely wants to make products that sell. Right now, the products they’re set up to sell happen to be computers and video games. Next year, they might be bicycles or fax machines.

The top execs at Commodore International don’t really understand why so many people love the Amiga. You see, to them, it’s as if customers were falling in love with a dishwasher or a brand of paper towels. Why would anybody love a computer? It’s just a chunk of hardware that we sell, fer cryin’ out loud.

— Amiga columnist “The Bandito,” Amazing Computing, January 1994

Commodore has never been known for their ability to arouse public support. They have never been noted for their ability to turn lemons into lemonade. But, they have been known to take a bad situation and create a disaster. At least there is some satisfaction in noting their consistency.

— Don Hicks, managing editor, Amazing Computing, July 1994

In the summer of 1992, loyal users of the Commodore Amiga finally heard a piece of news they had been anxiously awaiting for half a decade. At long last, Commodore was about to release new Amiga models sporting a whole new set of custom chips. The new models would, in other words, finally do more than tinker at the edges of the aging technology which had been created by the employees of little Amiga, Incorporated between 1982 and 1985. It was all way overdue, but, as they say, better late than never.

The story of just how this new chipset managed to arrive so astonishingly late is a classic Commodore tale of managerial incompetence, neglect, and greed, against which the company’s overtaxed, understaffed engineering teams could only hope to fight a rearguard action.

Commodore’s management had not woken up to the need to significantly improve the Amiga until the summer of 1988, after much of its technological lead over its contemporaries running MS-DOS and MacOS had already been squandered. Nevertheless, the engineers began with high hopes for what they called the “Advanced Amiga Architecture,” or the “AAA” chipset. It was to push the machine’s maximum screen resolution from 640 X 400 to 1024 X 768, while pushing its palette of available colors from 4096 to 16.8 million. The blitter and other pieces of custom hardware which made the machine so adept at 2D animation would be retained and vastly improved, even as the current implementation of planar graphics would be joined by “chunky-graphics” modes which were more suitable for 3D animation. Further, the new chips would, at the user’s discretion, do away with the flicker-prone interlaced video signal that the current Amiga used for vertical resolutions above 200 pixels, which made the machine ideal for desktop-video applications but annoyed the heck out of anyone trying to do anything else with it. And it would now boast eight instead of four separate sound channels, each of which would now offer 16-bit resolution — i.e., the same quality as an audio CD.

All of this was to be ready to go in a new Amiga model by the end of 1990. Had Commodore been able to meet that time table and release said model at a reasonable price point, it would have marked almost as dramatic an advance over the current state of the art in multimedia personal computing as had the original Amiga 1000 back in 1985.

Sadly, though, no plan at Commodore could long survive contact with management’s fundamental cluelessness. By this point, the research-and-development budget had been slashed to barely half what it had been when the company’s only products were simple 8-bit computers like the Commodore 64. Often only one engineer at a time was assigned to each of the three core AAA chips, and said engineer was more often than not young and inexperienced, because who else would work 80-hour weeks at the salaries Commodore paid? Throw in a complete lack of day-to-day oversight or management coordination, and you had a recipe for endless wheel-spinning. AAA fell behind schedule, then fell further behind, then fell behind some more.

Some fifteen months after the AAA project had begun, Commodore started a second chip-set project, which they initially called “AA.” The designation was a baseball metaphor rather than an acronym; the “AAA” league in American baseball is the top division short of the major leagues, while the “AA” league is one rung further down. As the name would indicate, then, the AA chipset was envisioned as a more modest evolution of the Amiga’s architecture, an intermediate step between the original chipset and AAA. Like the latter, AA would offer 16.8 million colors — of which 256 could be onscreen at once without restrictions, more with some trade-offs — but only at a maximum non-interlaced resolution of 640 X 480, or 800 X 600 in interlace mode. Meanwhile the current sound system would be left entirely alone. On paper, even these improvements moved the Amiga some distance beyond the existing Wintel VGA standard — but then again, that world of technology wasn’t standing still either. Much depended on getting the AA chips out quickly.

But “quick” was an adjective which seldom applied to Commodore. First planned for release on roughly the same time scale that had once been envisioned for the AAA chipset, AA too fell badly beyond schedule, not least because the tiny engineering team was now forced to split their energies between the two projects. It wasn’t until the fall of 1992 that AA, now renamed to the “Advanced Graphics Architecture,” or “AGA,” made its belated appearance. That is to say, the stopgap solution to the Amiga’s encroaching obsolescence arrived fully two years after the comprehensive solution to the problem ought to have shipped. Such was life at Commodore.

Rather than putting the Amiga out in front of the competition, AGA at this late date could only move it into a position of rough parity with the majority of the so-called “Super VGA” graphics cards which had become fairly commonplace in the Wintel world over the preceding year or so. And with graphics technology evolving quickly in the consumer space to meet the demands of CD-ROM and full-motion video, even the Amiga’s parity wouldn’t last for long. The Amiga, the erstwhile pioneer of multimedia computing, was now undeniably playing catch-up against the rest of the industry.

The Amiga 4000

AGA arrived inside two new models which evoked immediate memories of the Amiga 2000 and 500 from 1987, the most successful products in the platform’s history. Like the old Amiga 2000, the new Amiga 4000 was the “professional” machine, shipping in a big case full of expansion slots, with 4 MB of standard memory, a large hard drive, and a 68040 processor running at 25 MHz, all for a street price of around $2600. Like the old Amiga 500, the Amiga 1200 was the “home” model, shipping in an all-in-one-case form factor without room for internal expansion, with 2 MB of standard memory, a floppy drive only, and a 68020 processor running at 14 MHz, all for a price of about $600.

The two models were concrete manifestations of what a geographically bifurcated computing platform the Amiga had become by the early 1990s. In effect, the Amiga 4000 was to be the new face of Amiga computing in North America; ditto the Amiga 1200 in Europe. Commodore would make only scattered, desultory attempts to sell each model outside of its natural market.

Although the Amiga 500 had once enjoyed some measure of success in the United States as a games machine and general-purpose home computer, those days were long gone by 1992. That year, MS-DOS and Windows accounted for 87 percent of all American computer-game sales and the Macintosh for 9 percent, while the Amiga was lumped rudely into the 4 percent labeled simply “other.” Small wonder that very few American games publishers still gave any consideration to the platform at all; what games were still available for the Amiga in North America must usually be acquired by mail order, often as pricey imports from foreign climes. Then, too, most of the other areas where the Amiga had once been a player, and as often as not a pioneer — computer-based art and animation, 3D modeling, music production, etc. — had also fallen by the wayside, with most of the slack for such artsy endeavors being picked up by the Macintosh.

The story of Eric Graham was depressingly typical of the trend. Back in 1986, Graham had created a stunning ray-traced 3D animation called The Juggler on the Amiga; it became a staple of shop windows, filling at least some of the gap left by Commodore’s inept marketing. User demand had then led him to create Sculpt 3D, one of the first two practical 3D modeling applications for a consumer-class personal computer, and release it through the publisher Byte by Byte in mid-1987. (The other claimant to the status of absolute first of the breed ran on the Amiga as well; it was called Videoscape 3D, and was released virtually simultaneously with Sculpt 3D). But by 1989 the latest Macintosh models had also become powerful enough to support Graham’s software. Therefore Byte by Byte and Graham decided to jump to that platform, which already boasted a much larger user base who tended to be willing to pay higher prices for their software. Orphaned on the Amiga, the Sculpt 3D line continued on the Mac until 1996. Thanks to it and many other products, the Mac took over the lead in the burgeoning field of 3D modeling. And as went 3D modeling, so went a dozen other arenas of digital creativity.

The one place where the Amiga’s toehold did prove unshakeable was desktop video, where its otherwise loathed interlaced graphics modes were loved for the way they let the machine sync up with the analog video-production equipment typical of the time: televisions, VCRs, camcorders, etc. From the very beginning, both professionals and a fair number of dedicated amateurs used Amigas for titling, special effects, color correction, fades and wipes, and other forms of post-production work. Amigas were used by countless television stations to display programming information and do titling overlays, and found their way onto the sets of such television and film productions as Amazing Stories, Max Headroom, and Robocop 2. Even as the Amiga was fading in many other areas, video production on the platform got an enormous boost in December of 1990, when an innovative little Kansan company called NewTek released the Video Toaster, a combination of hardware and software which NewTek advertised, with less hyperbole than you might imagine, as an “all-in-one broadcast studio in a box” — just add one Amiga. Now the Amiga’s production credits got more impressive still: Babylon 5, seaQuest DSV, Quantum Leap, Jurassic Park, sports-arena Jumbotrons all over the country. Amiga models dating from the 1980s would remain fixtures in countless local television stations until well after the millennium, when the transition from analog to digital transmission finally forced their retirement.

Ironically, this whole usage scenario stemmed from what was essentially an accidental artifact of the Amiga’s design; Jay Miner, the original machine’s lead hardware designer, had envisioned its ability to mix and match with other video sources not as a means of inexpensive video post-production but rather as a way of overlaying interactive game graphics onto the output from an attached laser-disc accessory, a technique that was briefly en vogue in videogame arcades. Nonetheless, the capability was truly a godsend, the only thing keeping the platform alive at all in North America.

On the other hand, though, it was hard not to lament a straitening of the platform’s old spirit of expansive, experimental creativity across many fields. As far as the market was concerned, the Amiga was steadily morphing from a general-purpose computer into a piece of niche technology for a vertical market. By the early 1990s, most of the remaining North American Amiga magazines had become all but indistinguishable from any other dryly technical trade journal serving a rigidly specialized readership. In a telling sign of the times, it was almost universally agreed that early sales of the Amiga 4000, which were rather disappointing even by Commodore’s recent standards, were hampered by the fact that it initially didn’t work with the Video Toaster. (An updated “Video Toaster 4000” wouldn’t finally arrive until a year after the Amiga 4000 itself.) Many users now considered the Amiga little more than a necessary piece of plumbing for the Video Toaster. NewTek and others sold turnkey systems that barely even mentioned the name “Commodore Amiga.” Some store owners whispered that they could actually sell a lot more Video Toaster systems that way. After all, Commodore was known to most of their customers only as the company that had made those “toy computers” back in the 1980s; in the world of professional video and film production, that sort of name recognition was worth less than no name recognition at all.

In Europe, meanwhile, the nature of the baggage that came attached to the Commodore name perhaps wasn’t all that different in the broad strokes, but it did carry more positive overtones. In sheer number of units sold, the Amiga had always been vastly more successful in Europe than in North America, and that trend accelerated dramatically in the 1990s. Across the pond, it enjoyed all the mass-market acceptance it lacked in its home country. It was particularly dominant in Britain and West Germany, two of the three biggest economies in Europe. Here, the Amiga was nothing more nor less than a great games machine. The sturdy all-in-one-case design of the Amiga 500 and, now, the Amiga 1200 placed it on a continuum with the likes of the Sinclair Spectrum and the Commodore 64. There was a lot more money to be made selling computers to millions of eager European teenagers than to thousands of sober American professionals, whatever the wildly different price tags of the individual machines. Europe was accounting for as much as 88 percent of Commodore’s annual revenues by the early 1990s.

And yet here as well the picture was less rosy than it might first appear. While Commodore sold almost 2 million Amigas in Europe during 1991 and 1992, sales were trending in the wrong direction by the end of that period. Nintendo and Sega were now moving into Europe with their newest console systems, and Microsoft Windows as well was fast gaining traction. Thus it comes as no surprise that the Amiga 1200, which first shipped in December of 1992, a few months after the Amiga 4000, was greeted with sighs of relief by Commodore’s European subsidiaries, followed by much nervous trepidation. Was the new model enough of an improvement to reverse the trend of declining sales and steal a march on the competition once again? Sega especially had now become a major player in Europe, selling videogame consoles which were both cheaper and easier to operate than an Amiga 1200, lacking as they did any pretense of being full-fledged computers.

If Commodore was facing a murky future on two continents, they could take some consolation in the fact that their old arch-rival Atari was, as usual, even worse off. The Atari Lynx, the handheld game console which Jack Tramiel had bilked Epyx out of for a song, was now the company’s one reasonably reliable source of revenue; it would sell almost 3 million units between 1989 and 1994. The Atari ST, the computer line which had caused such a stir when it had beat the original Amiga into stores back in 1985 but had been playing second fiddle ever since, offered up its swansong in 1992 in the form of the Falcon, a would-be powerhouse which, as always, lagged just a little bit behind the latest Amiga models’ capabilities. Even in Europe, where Atari, like Commodore, had a much stronger brand than in North America, the Falcon sold hardly at all. The whole ST line would soon be discontinued, leaving it unclear how Atari intended to survive after the Lynx faded into history. Already in 1992, their annual sales fell to $127 million — barely a seventh those of Commodore.

Still, everything was in flux, and it was an open question whether Commodore could continue to sell Amigas in Europe at the pace to which they had become accustomed. One persistent question dogging the Amiga 1200 was that of compatibility. Although the new chipset was designed to be as compatible as possible with the old, in practice many of the most popular old Amiga games didn’t work right on the new machine. This reality could give pause to any potential upgrader with a substantial library of existing games and no desire to keep two Amigas around the house. If your favorite old games weren’t going to work on the new machine anyway, why not try something completely different, like those much more robust and professional-looking Windows computers the local stores had just started selling, or one of those new-fangled videogame consoles?

The compatibility problems were emblematic of the way that the Amiga, while certainly not an antique like the 8-bit generation of computers, wasn’t entirely modern either. MacOS and Windows isolated their software environment from changing hardware by not allowing applications to have direct access to the bare metal of the computer; everything had to be passed through the operating system, which in turn relied on the drivers provided by hardware manufacturers to ensure that the same program worked the same way on a multitude of configurations. AmigaOS provided the same services, and its technical manuals as well asked applications to function this way — but, crucially, it didn’t require that they do so. European game programmers in particular had a habit of using AmigaOS only as a bootstrap. Doing so was more efficient than doing things the “correct” way; most of the audiovisually striking games which made the Amiga’s reputation would have been simply impossible using “proper” programming techniques. Yet it created a brittle software ecosystem which was ill-suited for the long term. Already before 1992 Amiga gamers had had to contend with software that didn’t work on machines with more than 512 K of memory, or with a hard drive attached, or with or without a certain minor revision of the custom chips, or any number of other vagaries of configuration. With the advent of the AGA chipset, such problems really came home to roost.

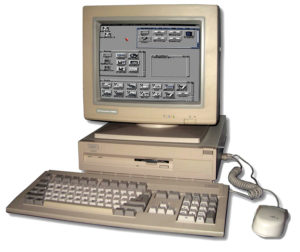

An American Amiga 1200. In the context of American computing circa 1992, it looked like a bizarrely antediluvian gadget. “Real” computers just weren’t sold in this style of all-in-one case anymore, with peripherals dangling messily off the side. It looked like a chintzy toy to Americans, whatever the capabilities hidden inside. A telling detail: notice the two blank keys on the keyboard, which were stamped with characters only in some continental European markets that needed them. Rather than tool up to produce more than one physical keyboard layout, Commodore just let them sit there in all their pointlessness on the American machines. Can you imagine Apple or IBM, or any other reputable computer maker, doing this? To Americans, and to an increasing number of Europeans as well, the Amiga 1200 just seemed… cheap.

Back in 1985, AmigaOS had been the very first consumer-oriented operating system to boast full-fledged preemptive multitasking, something that neither MacOS nor Microsoft Windows could yet lay claim to even in 1992; they were still forced to rely on cooperative multitasking, which placed them at the mercy of individual applications’ willingness to voluntarily cede time to others. Yet the usefulness of AmigaOS’s multitasking was limited by its lack of memory protection. Thanks to this lack, any individual program on the system could write, intentionally or unintentionally, all over the memory allocated to another; system crashes were a sad fact of life for the Amiga power user. AmigaOS also lacked a virtual-memory system that would have allowed more applications to run than the physical memory could support. In these respects and others — most notably its graphical interface, which still evinced nothing like the usability of Windows, much less the smooth elegance of the Macintosh desktop — AmigaOS lagged behind its rivals.

It is true that MacOS, dating as it did from roughly the same period in the evolution of the personal computer, was struggling with similar issues: trying to implement some form of multitasking where none at all had existed originally, kludging in support for virtual memory and some form of rudimentary memory protection. The difference was that MacOS was evolving, however imperfectly. While AmigaOS 3.0, which debuted with the AGA machines, did offer some welcome improvements in terms of cosmetics, it did nothing to address the operating system’s core failings. It’s doubtful whether anyone in Commodore’s upper management even knew enough about computers to realize they existed.

This quality of having one foot in each of two different computing eras dogged the platform in yet more ways. The very architectural approach of the Amiga — that of an ultra-efficient machine built around a set of tightly coupled custom chips — had become passé as Wintel and to a large extent even the Macintosh had embraced modular architectures where almost everything could live on swappable cards, letting users mix and match capabilities and upgrade their machines piecemeal rather than all at once. One might even say that it was down almost as much to the Amiga’s architectural philosophy as it was to Commodore’s incompetence that the machine had had such a devil of a time getting itself upgraded.

And yet the problems involved in upgrading the custom chips were as nothing compared to the gravest of all the existential threats facing the Amiga. It was common knowledge in the industry by 1992 that Motorola was winding down further development of the 68000 line, the CPUs at the heart of all Amigas. Indeed, Apple, whose Macintosh used the same CPUs, had seen the writing on the wall as early as the beginning of 1990, and had started projects to port MacOS to other architectures, using software emulation as a way to retain compatibility with legacy applications. In 1991, they settled on the PowerPC, a CPU developed by an unlikely consortium of Apple, IBM, and Motorola, as the future of the Macintosh. The first of the so-called “Power Macs” would debut in March of 1994. The whole transition would come to constitute one of the more remarkable sleights of hand in all computing history; the emulation layer combined with the ported version of MacOS would work so seamlessly that many users would never fully grasp what was really happening at all.

But Commodore, alas, was in no position to follow suit, even had they had the foresight to realize what a ticking time bomb the end of the 68000 line truly was. AmigaOS’s more easygoing attitude toward the software it enabled meant that any transition must be fraught with far more pain for the user, and Commodore had nothing like the resources Apple had to throw at the problem in any case. But of course, the thoroughgoing, eternal incompetence of Commodore’s management prevented them from even seeing the problem, much less doing anything about it. While everyone was obliviously rearranging the deck chairs on the S.S. Amiga, it was barreling down on an iceberg as wide as the horizon. The reality was that the Amiga as a computing platform now had a built-in expiration date. After the 68060, the planned swansong of the 68000 family, was released by Motorola in 1994, the Amiga would literally have nowhere left to go.

As it was, though, Commodore’s financial collapse became the more immediate cause that brought about the end of the Amiga as a vital computing platform. So, we should have a look at what happened to drive Commodore from a profitable enterprise, still flirting with annual revenues of $1 billion, to bankruptcy and dissolution in the span of less than two years.

During the early months of 1993, an initial batch of encouraging reports, stating that the Amiga 1200 had been well-received in Europe, was overshadowed by an indelibly Commodorian tale of making lemons out of lemonade. It turned out that they had announced the Amiga 1200 too early, then shipped it too late and in too small quantities the previous Christmas. Consumers had chosen to forgo the Amiga 500 and 600 — the latter being a recently introduced ultra-low-end model — out of the not-unreasonable belief that the generation of Amiga technology these models represented would soon be hopelessly obsolete. Finding the new model unavailable, they’d bought nothing at all — or, more likely, bought something from a competitor like Sega instead. The result was a disastrous Christmas season: Commodore didn’t yet have the new computers everybody wanted, and couldn’t sell the old computers they did have, which they’d inexplicably manufactured and stockpiled as if they’d had no inkling that the Amiga 1200 was coming. They lost $21.9 million in the quarter that was traditionally their strongest by far.

Scant supplies of the Amiga 1200 continued to devastate overall Amiga sales well after Christmas, leaving one to wonder why on earth Commodore hadn’t tooled up to manufacture sufficient quantities of a machine they had hoped and believed would be a big hit, for once with some justification. In the first quarter of 1993, Commodore lost a whopping $177.6 million on sales of just $120.9 million, thanks to a massive write-down of their inventory of older Amiga models piling up in warehouses. Unit sales of Amigas dropped by 25 percent from the same quarter of the previous year; Amiga revenues dropped by 45 percent, thanks to deep price cuts instituted to try to move all those moribund 500s and 600s. Commodore’s share price plunged to around $2.75, down from $11 a year before, $20 the year before that. Wall Street estimated that the whole company was now worth only $30 million after its liabilities had been subtracted — a drop of one full order of magnitude in the span of a year.

If anything, Wall Street’s valuation was generous. Commodore was now dragging behind them $115.3 million in debt. In light of this, combined with their longstanding reputation for being ethically challenged in all sorts of ways, the credit agencies considered them to be too poor a risk for any new loans. Already they were desperately pursuing “debt restructuring” with their major lenders, promising them, with little to back it up, that the next Christmas season would make everything right as rain again. Such hopes looked even more unfounded in light of the fact that Commodore was now making deep cuts to their engineering and marketing staffs — i.e., the only people who might be able to get them out of this mess. Certainly the AAA chipset, still officially an ongoing project, looked farther away than ever now, two and a half years after it was supposed to have hit the streets.

The Amiga CD32

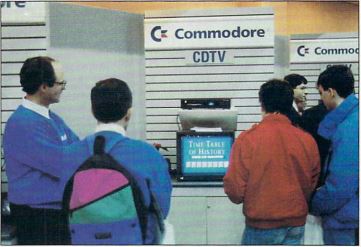

It was for these reasons that the announcement of the Amiga CD32, the last major product introduction in Commodore’s long and checkered history, came as such a surprise to everyone in mid-1993. CD32 was perhaps the first comprehensively, unadulteratedly smart product Commodore had released since the Amiga 2000 and 500 back in 1987. It was as clever a leveraging of their dwindling assets as anyone could ask for. Rather than another computer, it was a games console, built around a double-speed CD-ROM drive. Commodore had tried something similar before, with the CDTV unit of two and a half years earlier, only to watch it go down in flames. For once, though, they had learned from their mistakes.

CDTV had been a member of an amorphously defined class of CD-based multimedia appliances for the living room — see also the Philips CD-I, the 3DO console, and the Tandy VIS — which had all been or would soon become dismal failures. Upon seeing such gadgets demonstrated, consumers, unimpressed by ponderous encyclopedias that were harder to use and less complete than the ones already on their bookshelves, trip-planning software that was less intuitive than the atlases already in their glove boxes, and grainy film clips that made their VCRs look high-fidelity, all gave vent to the same plaintive question: “But what good is it really?” The only CD-based console which was doing well was, not coincidentally, the only one which could give a clear, unequivocal answer to this question. The Sega Genesis with CD add-on was good for playing videogames, full stop.

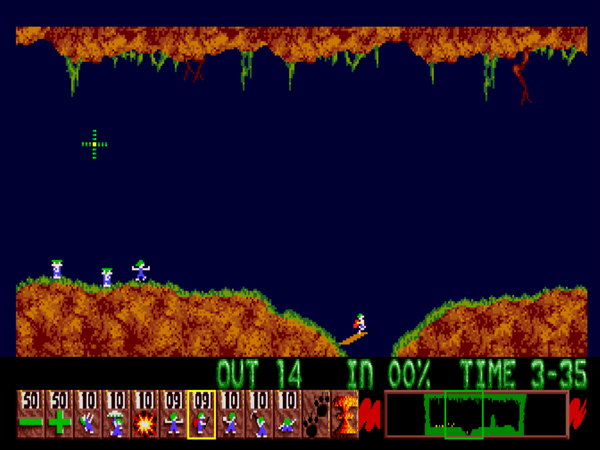

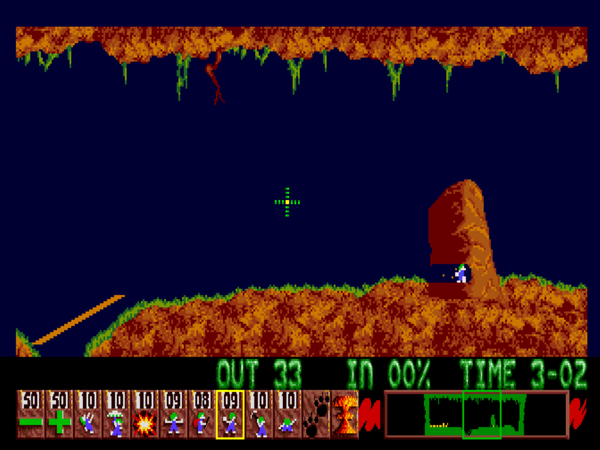

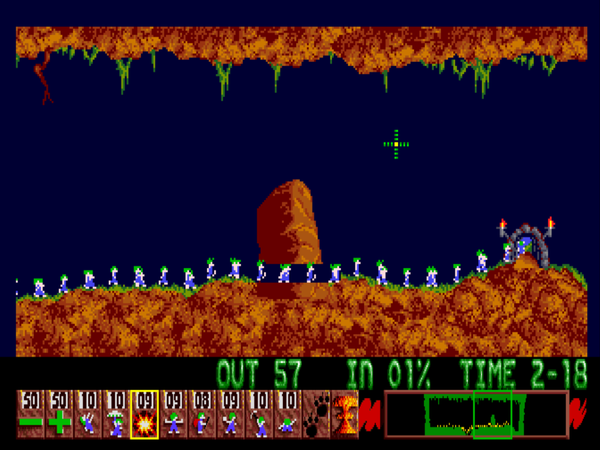

Commodore followed Sega’s lead with the CD32. It too looked, acted, and played like a videogame console — the most impressive one on the market, with specifications far outshining the Sega CD. Whereas Commodore had deliberately obscured the CDTV’s technological connection to the Amiga, they trumpeted it with the CD32, capitalizing on the name’s association with superb games. At heart, the CD32 was just a repackaged Amiga 1200, in the same way that the CDTV had been a repackaged Amiga 500. Yet this wasn’t a problem at all. For all that it was a little underwhelming in the world of computers, the AGA chipset was audiovisually superior to anything the console world could offer up, while the 32-bit 68020 that served as the CD32’s brain gave it much more raw horsepower. Meanwhile the fact that at heart it was just an Amiga in a new form factor gave it a huge leg up with publishers and developers; almost any given Amiga game could be ported to the CD32 in a week or two. Throw in a price tag of less than $400 (about $200 less than the going price of a “real” Amiga 1200, if you could find one), and, for the first time in years, Commodore had a thoroughly compelling new product, with a measure of natural appeal to people who weren’t already members of the Amiga cult. Thanks to the walled-garden model of software distribution that was the norm in the console world, Commodore stood to make money not only on every CD32 sold but also from a licensing fee of $3 on every individual game sold for the console. If the CD32 really took off, it could turn into one heck of a cash cow. If only Commodore could have released it six months earlier, or have managed to remain financially solvent for six months longer, it might even have saved them.

As it was, the CD32 made a noble last stand for a company that had long made ignobility its calling card. Released in September of 1993 in Europe, it generated some real excitement, thanks not least to a surprisingly large stable of launch titles, fruit of that ease of porting games from the “real” Amiga models. Commodore sold CD32s as fast as they could make them that Christmas — which was unfortunately nowhere near as fast as they might have liked, thanks to their current financial straits. Nevertheless, in those European stores where CD32s were on-hand to compete with the Sega CD, the former often outsold the latter by a margin of four to one. Over 50,000 CD32s were sold in December alone.

The Atari Jaguar. There was some mockery, perhaps justifiable, of its “Jetsons” design aesthetic.

Ironically, Atari’s last act took much the same form as Commodore’s. In November of 1993, following a horrific third quarter in which they had lost $17.6 million on sales of just $4.4 million, they released a game console of their own, called the Jaguar, in North America. In keeping with the tradition dating back to 1985, it was cheaper than Commodore’s take on the same concept — its street price was under $250 — but not quite as powerful, lacking a CD-ROM drive. Suffering from a poor selection of games, as well as reliability problems and outright hardware bugs, the Jaguar faced an uphill climb; Atari shipped less than 20,000 of them in 1993. Nevertheless, the Tramiel clan confidently predicted that they would sell 500,000 units in 1994, and at least some people bought into the hype, sending Atari’s stock soaring to almost $15 even as Commodore’s continued to plummet.

For the reality was, the rapid unraveling of all other facets of Commodore’s business had rendered the question of the CD32’s success moot. The remaining employees who worked at the sprawling campus in West Chester, Pennsylvania, purchased a decade before when the VIC-20 and 64 were flying off shelves and Jack “Business is War” Tramiel was stomping his rival home-computer makers into dust, felt like dwarfs wandering through the ancient ruins of giants. Once there had been more than 600 employees here; now there were about 50. There was 10,000 square feet of space per employee in a facility where it cost $8000 per day just to keep the lights on. You could wander for hours through the deserted warehouses, shuttered production lines, and empty research labs without seeing another living soul. Commodore was trying to lease some of it out for an attractive rent of $4 per square foot, but, as with with most of their computers, nobody seemed all that interested. The executive staff, not wanting the stigma of having gone down with the ship on their resumes, were starting to jump for shore. Commodore’s chief financial officer threw up his hands and quit in the summer of 1993; the company’s president followed in the fall.

Apart from the CD32, for which they lacked the resources to manufacture enough units to meet demand, virtually none of the hardware piled up in Commodore’s European warehouses was selling at all anymore. In the third quarter of 1993, they lost $9.7 million, followed by $8 million in the fourth quarter, on sales of just $70 million. After a second disastrous Christmas in a row, it could only be a question of time.

In a way, it was the small things rather than the eye-popping financial figures which drove the point home. For example, the April 1994 edition of the New York World of Commodore show, for years already a shadow of its old vibrant self, was cancelled entirely due to lack of interest. And the Army and Air Force Exchange, which served as a storefront to American military personnel at bases all over the world, kicked Commodore off its list of suppliers because they weren’t paying their bills. It’s by a thousand little cuts like this one, each representing another sales opportunity lost, that a consumer-electronics company dies. At the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January of 1994, at which Commodore did manage a tepid presence, their own head of marketing told people straight out that the Amiga had no future as a general-purpose computer; Commodore’s only remaining prospects, he said, lay with the American vertical market of video production and the European mass market of videogame consoles. But they didn’t have the money to continue building the hardware these markets were demanding, and no bank was willing to lend them any.

The proverbial straw which broke the camel’s back was a dodgy third-party patent relating to a commonplace programming technique used to keep a mouse pointer separate from the rest of the screen. Commodore had failed to pay the patent fee for years, the patent holder eventually sued, and in April of 1994 the court levied an injunction preventing Commodore from doing any more business at all in the United States until they paid up. The sum in question was a relatively modest $2.5 million, but Commodore simply didn’t have the money to give.

On April 29, 1994, in a briefly matter-of-fact press release, Commodore announced that they were going out of business: “The company plans to transfer its assets to unidentified trustees for the benefit of its creditors. This is the initial phase of an orderly voluntary liquidation.” And just like that, a company which had dominated consumer computing in the United States and much of Europe for a good part of the previous decade and a half was no more. The business press and the American public showed barely a flicker of interest; most of them had assumed that Commodore was already long out of business. European gamers reacted with shock and panic — few had realized how bad things had gotten for Commodore — but there was nothing to be done.

Thus it was that Atari, despite being chronically ill for a much longer period of time, managed to outlive Commodore in the end. Still, this isn’t to say that their own situation at the time of Commodore’s collapse was a terribly good one. When the reality hit home that the Jaguar probably wasn’t going to be a sustainable gaming platform at all, much less sell 500,000 units in 1994 alone, their stock plunged back down to less than $1 per share. In the aftermath, Atari limped on as little more than a patent troll, surviving by extracting judgments from other videogame makers, most notably Sega, for infringing on dubious intellectual property dating back to the 1970s. This proved to be an ironically more profitable endeavor for them than that of actually selling computers or game consoles. On July 30, 1996, the Tramiels finally cashed out, agreeing to merge the remnants of their company with JT Storage, a maker of hard disks, who saw some lingering value in the trademarks and the patents. It was a liquidation in all but name; only three Atari employees transitioned to the “merged” entity, which continued under the same old name of JT Storage.

And so disappeared the storied name of Atari and that of Tramiel simultaneously from the technology industry. Even as the trade magazines were publishing eulogies to the former, few were sorry to see the latter go, what with their long history of lawsuits, dirty dealing, and abundant bad faith. Jack Tramiel had purchased Atari in 1984 out of the belief that creating another phenomenon like the Commodore 64 — or for that matter the Atari VCS — would be easy. But the twelve years that followed were destined always to remain a footnote to his one extraordinary success, a cautionary tale about the dangers of conflating lucky timing and tactical opportunism with long-term strategic genius.

Even so, the fact does remain that the Commodore 64 brought affordable computing to millions of people all over the world. For that every one of those millions owes Jack Tramiel, who died in 2012, a certain debt of gratitude. Perhaps the kindest thing we can do for him is to end his eulogy there.

The story of the Amiga after the death of Commodore is long, confusing, and largely if not entirely dispiriting; for all these reasons, I’d rather not dwell on it at length here. Its most positive aspect is the surprisingly long commercial half-life the platform enjoyed in Europe, over the course of which game developers still found a receptive if slowly dwindling market ready to buy their wares. The last glossy newsstand magazine devoted to the Amiga, the British Amiga Active, didn’t publish its last issue until the rather astonishingly late date of November of 2001.

The Amiga technology itself first passed into the hands of a German PC maker known as Escom, who actually started manufacturing new Amiga 1200s for a time. In 1996, however, Escom themselves went bankrupt. The American PC maker Gateway 2000 became the last major company to bother with the aging technology when they bought it at the Escom bankruptcy auction. Afterward, though, they apparently had second thoughts; they did nothing whatsoever with it before selling it onward at a loss. From there, it passed into other, even less sure hands, selling always at a discount. There are still various projects bearing the Amiga name today, and I suspect they will continue until the generation who fell in love with the platform in its heyday have all expired. But these are little more than hobbyist endeavors, selling their products in minuscule numbers to customer motivated more by their nostalgic attachment to the Amiga name than by any practical need. It’s far from clear what the idea of an “Amiga computer” should even mean in 2020.

When the hardcore of the Amiga hardcore aren’t dreaming quixotically of the platform’s world-conquering return, they’re picking through the rubble of the past, trying to figure out where it all went wrong. Among a long roll call of petty incompetents in Commodore’s executive suites, two clear super-villains emerge: Irving Gould, Commodore’s chairman since the mid-1960s, and Mehdi Ali, his final hand-picked chief executive. Their mismanagement in the latter days of the company was so egregious that some have put it down to evil genius rather than idiocy. The typical hypothesis says that these two realized at some point in the very early 1990s that Commodore’s days were likely numbered, and that they could get more out of the company for themselves by running it into the ground than they could by trying to keep it alive. I usually have little time for such conspiracy theories; as far as I’m concerned, a good rule of thumb for life in general is never to attribute to evil intent what can just as easily be chalked up to good old human stupidity. In this case, though, there’s some circumstantial evidence lending at least a bit of weight to the theory.

The first and perhaps most telling piece of evidence is the two men’s ridiculously exorbitant salaries, even as their company was collapsing around them. In 1993, Mehdi Ali took home $2 million, making him the fourth highest-paid executive in the entire technology sector. Irving Gould earned $1.75 million that year — seventh on the list. Why were these men paying themselves as if they ran a thriving company when the reality was so very much the opposite? One can’t help but suspect that Gould at least, who owned 19 percent of Commodore’s stock, was trying to offset his losses on the one field by raising his personal salary on the other.

And then there’s the way that Gould, an enormously rich man whose personal net worth was much higher than that of all of Commodore by the end, was so weirdly niggardly in helping his company out of its financial jam. While he did loan fully $17.4 million back to Commodore, the operative word here is indeed “loan”: he structured his cash injections to ensure that he would be first in line to get his money back if and when the company went bankrupt, and stopped throwing good money after bad as soon as the threshold of the collateral it could offer up in exchange was exceeded. One can’t help but wonder what might have become of the CD32 if he’d been willing to go all-in to try to turn it into a success.

Of course, this is all rank speculation, which will quickly become libelous if I continue much further down this road. Suffice to say that questionable ethics were always an indelible part of Commodore. Born in scandal, the company would quite likely have ended in scandal as well if anyone in authority had been bothered enough by its anticlimactic bankruptcy to look further. I’d love to see what a savvy financial journalist could make of Commodore’s history. But, alas, I have neither the skill nor the resources for such a project, and the story is of little interest to the mainstream journalists of today. The era is past, the bodies are buried, and there are newer and bigger outrages to fill our newspapers.

Instead, then, I’ll conclude with two brief eulogies to mark the end of the Amiga’s role in this ongoing history. Rather than eulogizing in my own words, I’m going to use those of a true Amiga zealot: the anonymous figure known as “The Bandito,” whose “Roomers” columns in the magazine Amazing Computing were filled with cogent insights and nitty-gritty financial details every month. (For that reason, they’ve been invaluable sources for this series of articles.)

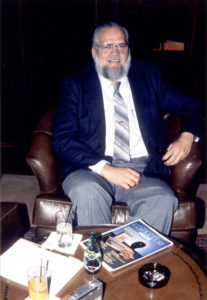

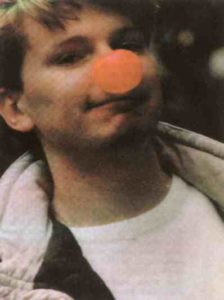

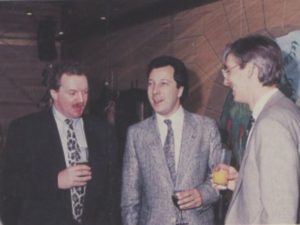

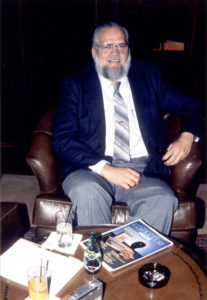

Jay Miner, the gentle genius, in 1990. In interviews like the one to which this photo was attached, he always seemed a little befuddled by the praise and love which Amiga users lavished upon him.

First, to Jay Miner, the canonical “father of the Amiga,” who died of the kidney disease he had been battling for most of his life on June 20, 1994, at age 62. If a machine can reflect the personality of a man, the Amiga certainly reflected his:

Jay was not only the inventive genius who designed the custom chips behind the Atari 800 and the Amiga, he also designed many more electronic devices, including a new pacemaker that allows the user to set their own heart rate (which allows them to participate in strenuous activities once denied to them). Jay was not only a brilliant engineer, he was a kind, gentle, and unassuming man who won the hearts of Amiga fans everywhere he went. Jay was continually amazed and impressed at what people had done with his creations, and he loved more than anything to see the joy people obtained from the Amiga.

We love you, Jay, for all the gifts that you have given to us, and all the fruits of your genius that you have shared with us. Rest in peace.

And now a last word on the Amiga itself, from the very last “Roomers” column, written by someone who had been there from the beginning:

The Amiga has left an indelible mark on the history of computing. [It] stands as a shining example of excellent hardware design. Its capabilities foreshadowed the directions of the entire computer industry: thousands of colors, multiple screen resolutions, multitasking, high-quality sound, fast animation, video capability, and more. It was the beauty and elegance of the hardware that sold the Amiga to so many millions of people. The Amiga sold despite Commodore’s neglect, despite their bumbling and almost criminal marketing programs. Developers wrote brilliantly for this amazing piece of hardware, creating software that even amazed the creators of the hardware. The Amiga heralded the change that’s even now transforming the television industry, with inexpensive CGI and video editing making for a whole new type of television program.

Amiga game software also changed the face of entertainment software. Electronic Arts launched themselves headlong into 16-bit entertainment software with their Amiga software line, which helped propel them into the $500 million giant they are today. Cinemaware’s Defender of the Crown showed people what computer entertainment could look like: real pictures, not blocky collections of pixels. For a while, the Amiga was the entertainment-software machine to have.

In light of all these accomplishments, the story of the Amiga really isn’t the tragedy of missed opportunities and unrealized potential that it’s so often framed as. The very design that made it able to do so many incredible things at such an early date — its tightly coupled custom chips, its groundbreaking but lightweight operating system — made it hard for the platform to evolve in the same ways that the less imaginative, less efficient, but modular Wintel and MacOS architectures ultimately did. While it lasted, however, it gave the world a sneak preview of its future, inspiring thousands who would go on to do good work on other platforms. We are all more or less the heirs to the vision embodied in the original Amiga Lorraine, whether we ever used a real Amiga or not. The platform’s most long-lived and effective marketing slogan, “Only Amiga Makes it Possible,” is of course no longer true. It is true, though, that the Amiga made many things possible first. May it stand forever in the annals of computing history alongside the original Apple Macintosh as one of the two most visionary computers of its generation. For without these two computers — one of them, alas, more celebrated than the other — the digital world that we know today would be a very different place.

(Sources: the books Commodore: The Final Years by Brian Bagnall and my own The Future Was Here; Amazing Computing of November 1992, December 1992, January 1993, February 1993, March 1993, April 1993, May 1993, June 1993, July 1993, September 1993, October 1993, November 1993, December 1993, January 1994, February 1994, March 1994, April 1994, May 1994, June 1994, July 1994, August 1994, September 1994, October 1994, and February 1995; Byte of January 1993; Amiga User International of June 1988; Electronic Gaming Monthly of June 1995; Next Generation of December 1996. My thanks to Eric Graham for corresponding with me about The Juggler and Sculpt 3D years ago when I was writing my book on the Amiga.

Those wishing to read about the Commodore story from the perspective of the engineers in the trenches, who so often accomplished great things in less than ideal conditions, should turn to Brian Bagnall’s full “Commodore Trilogy”: A Company on the Edge, The Amiga Years, and The Final Years.)