Excepting only Adventure and a handful of works by Infocom, Robert Pinsky’s Mindwheel has received far more academic attention than any other work of interactive fiction’s commercial era. If you’re of a practical — not to say cynical — turn, you can posit a pretty good theory as to why that should be without ever looking to the game itself. Pinsky, you see, is by far the most respectable and respected literary figure ever to turn his hand to the humble text adventure. His resume is impressive to say the least: United States Poet Laureate from 1997 to 2000; author of nineteen books, nine of them full of poems; translator of Dante; professor of literature at Berkeley and Boston University amongst other places; editor of literary magazines and anthologies; scholar of the Biblical David and Shakespeare. For any graduate student looking to justify a thesis or article about interactive fiction, Pinsky is a riposte to die for when colleagues and advisers ask whether text adventures are really all that significant as literary works. If they were good enough for Pinsky, they should be good enough for anyone.

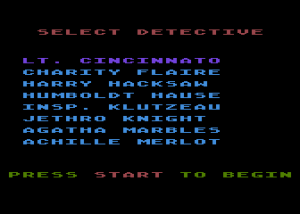

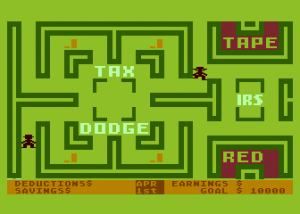

Mindwheel is the product of a strange historical moment; it’s hard to imagine it appearing more than a year before or after its February 1985 release date. This was the era of bookware, when interactive fiction was seen as the future of the book and the future of computerized entertainment all rolled into one; when action games were seen as relics of the recently passed age of the Atari VCS; when a company called Synapse Software, known already as the makers of some of the slickest and most graphically impressive action games on the Atari 8-bit line, could decide to stake much of their future on textual interactive fiction not out of some suicidal artistic impulse but because doing so seemed a perfectly reasonable commercial calculation. Strange, strange times.

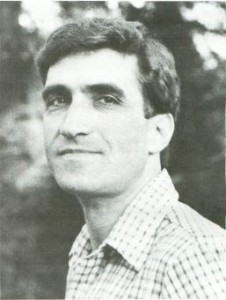

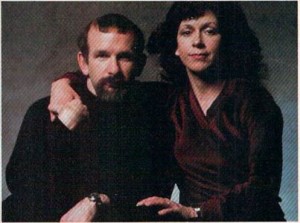

The story of Synapse Software is largely the story of Ihor Wolosenko, whose family had immigrated to the United States from Ukraine when he was still a toddler and who had filled the nearly forty years that elapsed in his life before Synapse with a bewildering array of activities and avocations. He had studied drama at the City University of New York; been a professional photographer; worked as a physical therapist; counseled and conducted personal workshops using a combination of Tibetan Buddhism and the controversial branch of psychology known as neuro-linguistic programming; delved deeply into linguistics and hypnosis. By 1980, the year he bought an Atari 800, he had ended up like so many other drifting dreamers in Berkeley, California. He chose the Atari because it could play Star Raiders and the Apple II couldn’t.

Wolosenko soon made a more technical friend, a vice president in charge of data processing at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank named Ken Grant who had been toying with an Atari 800 database application in his spare time. The two worked on it together for nearly a year, then founded Synapse out of Wolosenko’s apartment to release it in August of 1981. It wasn’t an auspicious start; the first hundred or so copies of FileManager 800 that they shipped were so buggy that they had to recall the whole production run. But by the end of the year Synapse was truly up and running at last, with not just FileManager but a game or two as well.

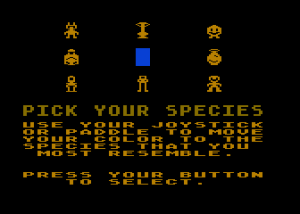

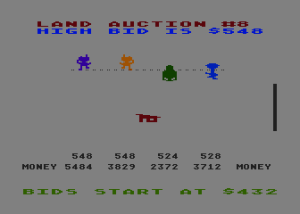

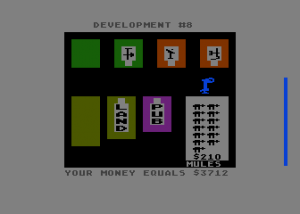

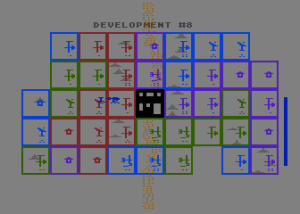

Wolosenko was already putting together the team of crack programmers whose games would make Synapse’s reputation. Games like Shamus, Blue Max, The Pharaoh’s Curse, and their most beloved title of all Alley Cat mixed superb graphics with addictive playability and a welcome sense of whimsy. Little extra touches distinguished Synapse’s games from the competition. In Alley Cat, for instance, if you don’t do anything for a few seconds your avatar will start to move around on his own and meow impatiently to you, decades before such “juicy” touches would become a widely accepted requirement for casual games.

It wouldn’t be out of line to compare Synapse’s mystique in North America with that of Ultimate Play the Game in Britain. Both developed all of their games in-house, insuring that they all shared a similar look and design sensibility. Both were absolute masters of their chosen platforms (the Spectrum for Ultimate, the Atari 8-bits for Synapse) and consistently delivered games that were far slicker than virtually anything the competition had to offer. Synapse, like Ultimate, did write for other platforms, but their core competency and core loyalty remained with the Atari machines. Atari users in turn loved them. Because Synapse’s games were born on Ataris, they could take full advantage of the best graphics and sound in the industry, capabilities matched only (and if you listen to Atari loyalists only arguably) by those of the Commodore 64.

While Wolosenko usually refused formal credit on his programmers’ designs, much of the character of Synapse’s games was down to him. His company may have been making relatively simple action games, but he nevertheless thought seriously about the nature of the medium, the relationship between player and avatar, the standard approach of graduated difficulty levels (bad) and the alternative of adaptive gameplay (good). He shepherded every game and every programmer through the process of development, giving a little nudge here, a little tweak there to make the end result that much better. Synapse programmer Steve Hales called Wolosenko the Steve Jobs of games: “Every product that Synapse produced had Ihor’s touch. I believe that because of Ihor our quality was better, the designs were more unique, and I was pushed beyond what I thought was possible.”

According to Hales, it was he and another of Wolosenko’s favorite programmers, William Mataga, who planted the idea of doing adventure games in Wolosenko’s head in late 1983. (William Mataga now lives as Cathryn Mataga. I refer to her by her previous name and gender in this article only to avoid historical anachronisms.) Hales and Mataga believed that Infocom had “old technology,” and Synapse could do better. Wolosenko didn’t take much convincing. Showing his usual enthusiasm, he laid out an ambitious if not entirely cogent manifesto for Synapse’s engine, which would be the work largely of Mataga.

The problem with these adventure games thus far, even the more interactive ones, is that you have the feeling of being in a corral. You go this way and someone says, “You can’t go that way.” If I say, “Toss something,” and it says, “I don’t understand that word,” when it just used that word in a description it drives me up the wall. It totally stops the experience for me. We’re going to have to work with some of those obstructions until we can solve some of the problems: not processing time, just putting the computer’s power to better use.

The most intricate puzzle is not a Rubik’s Cube, it’s a person. And it’s a character that changes. When you read bad fiction, the character comes in, he interacts with a lot of people, and he goes out exactly the way he came in. When you read a Tolstoy novel, the character is totally different at the end of the novel than when he came in at the beginning. And that’s what we’re trying to do. There is no reason why you have to be the same person during a game either. You could have a changeling-type game, where you’re a person at one point, you’re a dog at another, a bat at another.

Mataga dubbed his system BTZ — “Better than Zork” — to keep the end goal inescapable for everyone. Crucially, the vision was for pure text from the outset. Whereas rivals like Telarium sought to one-up Infocom by adding graphics and sound and even occasional action games to the mix to hopefully distract from their less than Infocom-quality parsers, prose, and world models, Synapse would go against them head to head, strength against strength. The games themselves Wolosenko first wanted to call “Microworlds” in light of the freedom and sense of realism they would offer. That soon changed, however, when he had his next brain storm: to hire the best outside writers he could find — real writers — to craft the worlds and write the text. His Microworlds thus became Electronic Novels.

There is some evidence that the poet Robert Pinsky was far from Wolosenko’s first choice to craft the first Electronic Novel. In an interview published in the February 1984 issue of Ahoy! magazine, he claimed that, while the contracts were not yet all signed, Synapse hoped to be employing the services of “top, top novelists [emphasis mine].” But Telarium and many others, some with pockets and connections much deeper than Synapse’s, were already trolling these waters. Wolosenko apparently soon decided that, if he couldn’t sign “top” writers in terms of sales and commercial appeal, he could hire the most prestigious, thereby underscoring the literary credibility of Synapse’s line. Somehow he jumped to the inspired choice of targeting not novelists but poets; perhaps he figured that, what with the term “popular poet” having been largely an oxymoron for decades already, they’d be more likely to jump at the chance for any sort of recognition. Surveying the possibilities, he came across the name of Robert Pinsky, who was teaching at UC Berkeley and thus an easy mark logistically. The resume of Pinsky, then about the same age as Wolosenko, was nowhere near as impressive as it is today, but he nevertheless had a burgeoning literary reputation, with two well-received books of poetry already published and a third in the galley stage. (Wolosenko would soon also tap another respected young poet, Jim Paul, for another game in the line.)

One day as Pinsky was sitting in his office in Berkeley’s English department having spent the last several hours dealing with some of the more tedious administrative details that come with being a professor, his phone rang. It was Ihor Wolosenko on the line.

He said, “Are you familiar with computer text adventures?”

I said, “No.”

He asked whether I owned a computer.

I said, “No.”

Had I ever heard of Zork?

“No.”

Would I be interested in writing the text for an interactive computer work?

I said, “Yes, I might be.”

Pinsky drove out to visit Synapse’s offices. Wolosenko introduced him to some of his programmers and also to the concept of text adventures.

I liked it. My romantic idea was that it was like those first guys figuring out what movies were going to be on Long Island — playing with movie cameras. I didn’t see any reason that you couldn’t make a work of art. Art is alternate realities — realities that are in some ways like the reality we experience and in some ways quite unlike it. This was that. And it was clear to me from my small experience of adventures — the description of Zork, the stuff I saw on those monochrome monitors — that this was largely about the quest plot, one of the basic plots of great works. The Gilgamesh epic is a quest for the nature of immortality — or the nature of death, the nature of mortality. “KILL DWARF,” “GET SWORD,” etc., was completely in that line. Indeed, the imagery was very traditional.

It was agreed that Pinsky would come up with five or six ideas for possible games. Then Synapse would decide which one might be the most intriguing and realizable. The one that Pinsky himself considered the “silliest” sent the player on a journey through four minds: an assassinated rock star with a messiah complex, clearly modeled on John Lennon; a bloody dictator inspired by Hitler and Stalin and the rest of the twentieth century’s sad litany; a brilliant scientist reminiscent of Marie Curie; and a poet, a nod to the game’s creator himself. Much to Pinsky’s surprise, this treatment was the one that Wolosenko and company opted for.

One of the loveliest aspects of the Mindwheel project is the genuinely warm, respectful relationship that developed between Pinsky and the young hackers at Synapse, these men who normally inhabited what might as well have been separate planets. Pinsky worked most closely with Steve Hales, who did the actual coding for the game in Mataga’s BTZ language. Hales, who had never voluntarily read a line of verse in his life, slowly discovered through the soft-spoken, thoughtful Pinsky a new respect for the written word and the power of literature: “He changed the way I read and write words forever.” For his part, Pinsky found the youthful can-do spirit at Synapse a relief from the “oppressive” corridors of academia; he was soon “making up excuses” to visit Synapse and “hang out.” Hales endeared himself to Pinsky from his first words: “I’d like to talk to you about your world,” a turn of phrase Pinsky found almost inexpressibly fresh and exciting. He took to using — and often charmingly misusing — the fascinating jargon, a delight to his poet’s soul, that was always flying through the air at Synapse. He accepted what he wryly refers to as his “assignments” from Hales and company with cheerful equanimity: write a “dialog table” for a given character for queries involving a given set of topics; write responses in which each of these fifty verbs is used successfully and unsuccessfully. The terms attached to even the framework of the game took a poetic turn under Pinsky’s influence, with “drivel” coming to mean amusing incidental messages that were essentially random, not germane to the plot or puzzles, and “weather” those that were.

While the experience of actually developing Mindwheel was by everyone’s account an almost entirely positive one, its story is also one of crossed purposes between Pinsky and Wolosenko. Wolosenko clearly wanted to create a work of art that transcended the notion of a mere computer game. Thus the involvement of Pinsky in the first place, as well as the term “Computer Novel” and his plan to package each title in the line inside a hardcover book of at least a hundred pages. (This latter was also, of course, a challenge to Infocom’s superb packaging, yet another reflection of a determination to do “everything that Infocom does, plus one.”) Pinsky, meanwhile, took the project as a chance to let his hair down and maybe reach the sort of popular readership that had inevitably eluded him thus far despite his stellar reputation inside the ivory tower. He was teaching a class about Shakespeare at the time, and thinking a lot about how the Bard had become the greatest writer in the history of the English language not by appealing to the highbrows but by writing popular entertainments for the masses. (Pinsky still remains admirably free of literary snobbery today, listing for example South Park as one of the “tremendous works of our time,” its creators amongst our “leading moralizers.”)

The idea of making the package for Mindwheel into a hardcover book was very much Ihor Wolosenko’s idea. I didn’t like it; I resisted it. I happened to refer to what we were doing as “the game.” To me, that was fresh and exciting. The guys at Synapse who were promoting it wanted to call it an “Electronic Novel,” because from their viewpoint that was fresh and interesting.

I was disappointed that the package would be a book. They wanted me to write the stuff for the book. I declined. It was produced by committee; I wound up sort of editing it. The book was the least interesting part for me. I’ve written books; I’ve published lots of books; I wasn’t particularly excited by the romance of having a book. Ihor’s marketing idea was that this would be somehow “highbrow.” I liked the idea that it was an entertainment, that it was a game. I wanted to get away from the “literary” genre. I wanted to write a really exciting, artistic game.

Pinsky noted in a contemporary interview that he didn’t particularly care if Mindwheel got a writeup in The Paris Review because his name had already appeared there many times. Wolosenko, of course, would have killed for such a marker of literary status.

The book, which is credited to BTZ project manager Richard Stanford, is a rather labored piece; it’s quite clear that Synapse struggled to come up with material to fill its pages, resorting to leaving dozens of pages entirely blank in the name of an “Adventurer’s Diary” for note taking. Those pages which are filled strain to set up a believable science-fictional reason for the mind-delving you do in the game proper. It seems that the social order on Earth is about to collapse thanks to humankind’s ongoing irresponsibility and the sheer inertia of thousands of years of petty human history. The only hope for salvation rests, for reasons poorly defined at best, in the science of “neuro-electronic matrix research” (the terminological similarity to Wolosenko’s personal interest of neuro-linguistic programming is interesting), which will allow a traveler to visit “four minds of unusual power” whose echoes still persist in the very atmosphere — shades of Carl Jung’s ideas about a collective unconscious. The four minds will eventually lead you to the “Cave Master,” “the mysterious prehistoric, apelike being who apparently invented the lever, the flint blade, cave paintings, and the rhythmical group chant” and who holds the “Wheel of Wisdom” that can save humankind. The winning passage of Mindwheel, after the Wheel has been retrieved, indicates about how seriously Pinsky took this earnest frame.

"This formula," says Virgil through happy tears, "can disable every weapon of mass destruction on the planet! And that is only the first benefit. Your courage and brains have given us a glorious new chance!

"Already, the planet's magnetic field is changed, so that any politician who lies on television will be afflicted with instant, debilitating diarrhea, and immediate, spectacular skin blemishes!"

He beams and detaches your electrodes.

Exalted but a little drained, you wish only to rest a while, and then unwind, maybe by playing some harmless game.

No, Mindwheel is more electronic poem than electronic novel. The world of the four minds is a surrealistic, impressionistic riot of emotional imagery. The premise and that very description raise immediate warning flags to a jaded old IFer like me; the history of amateur interactive fiction is strewn with surrealistic explorations of the inner consciousness, generally from younger writers with a wide streak of overwrought self-indulgence. They’re almost uniformly awful. But — to state the obvious — the authors of these works are (presumably) not future Poet Laureates. Pinsky’s prose is bracing, his imagery consistently surprising and consistently as right as it is bizarre. To play Mindwheel is an overwhelming sensory experience — even as all of its sensations are evoked through pure text.

The first mind you enter is that of Bobby Clemons, the rock star.

You stand on an immense stage. In front of you, a crowd roars like thunder. Someone has thrown a rose and a Baby Ruth candy bar onto the stage. High overhead, a huge video screen displays, over and over, the film of Bobby Clemons' assassination. In tight, sequined costumes, a chorus of singers writhes, imitating the gestures of the fatally wounded figure on the screen.

A ramp juts south into the crowd that pleads for you to come forward. A keyboard is on the east part of the stage, while to the west, some thugs seem about to overpower your bodyguard. They have clubs, and you hold only your harmonica; your pockets are empty. While the crowd screams for more, one of the singers beckons you to come offstage by the door northward behind you.

The scene is vaguely hilarious and vaguely disturbing. As you stalk the stage panties are flying, dancers are grinding, bodyguards and thugs are brawling, and the crowd is baying for your love or your blood, or more likely both. It’s rock and roll in all its Dionysian danger and splendor. The other minds are only slightly less crowded and just as evocative: the poet’s full of more wistful imagery of sex and love and life and death; the dictator’s, a barren, ugly place of stunted growth and pathetic posturing; the scientist’s, an immense chess board of cool, classical beauty.

The obvious literary antecedent of the whole endeavor is Dante’s The Divine Comedy, particularly its first part The Inferno. Pinsky makes his homage about as explicit as homages can be by naming the scientist who sends you on your journey into the minds Doctor Virgil, a reference to the Roman poet who served as Dante’s guide to humanity in all its facets. Other more subtle references are sprinkled throughout Mindwheel. More importantly, the feel of the environment is similar. Dante has been a long-term fixation of Pinsky, resulting most notably in the popular translation of The Inferno which he published a decade after Mindwheel, and which has led Nick Montfort to cheekily note Mindwheel as “the first work of interactive fiction to have influenced The Inferno.”

Like The Divine Comedy, Mindwheel manages to be personal as well as epic. Amidst all the other imagery you’ll find within it a brief homage to Pinsky’s early mentor, the iconoclastic poet Yvor Winters, as well as a more extended one to the Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s, those “boys of summer” who are the subject of the best book ever written about baseball. Indeed, the final puzzle of the game is a technically unfair one which requires you to do a bit of outside research into the only Brooklyn team to win the World Series. But go ahead and do the research; it’s good for you, and it’s trivial in the age of the Internet. Pinsky, who grew up in neighboring New Jersey, obviously followed the Brooklyn Bums and loved them dearly, obviously was as heartbroken as the rest of their fans when the team upped and moved to Los Angeles.

But the most personal of all parts of Mindwheel is, as you might expect, your excursion into the mind of the poet. Pinsky has since noted that one of the few sources of occasional tension between him and Hales stemmed from the former’s desire to just keep piling on more crazy world to explore while the latter insisted that there needed to be puzzles, pacing, the structure that would result in a real game with a score of sorts — presented as a summarized list of your achievements rather than a numerical value — and the possibility for victory. (Yes, this would seem to suddenly put Pinsky and Synapse on the opposite sides of the positions they had already staked in the novel/game dialectic. What can I say, other than that few philosophical positions survive contact with practicality.) Still, and for all that they were apparently a somewhat grudging addition on Pinsky’s part, Mindwheel‘s puzzles are mostly pretty good, managing to serve the themes with an emphasis on poetics, dialog, and symbolism rather than a bunch of mechanistic operations. Occasionally they’re more than pretty good, as in the case of the most intricate, rewarding, and personal puzzle of all: the completion of a sonnet using words gathered from the environment around you. The sonnet in question originated with the Renaissance poet Fulke Greville. The lines were, however, too long to fit on the 40-column screens used by many of Synapse’s customers, so Pinsky converted the poem from pentameter to tetrameter. The puzzle is brilliant because it so perfectly connects with the daily labors of the mind you’re exploring. You’re counting beats, looking at the rhyme scheme, seeking that word that fits mechanically and also just, well, fits. Pinsky, who labored always to find ways to make poetry relevant in people’s lives, was delighted when he saw a group of playtesting high-school kids “just trying to figure them [the sonnet and some other poetry-related puzzles] out because they’re having fun and want to do it.”

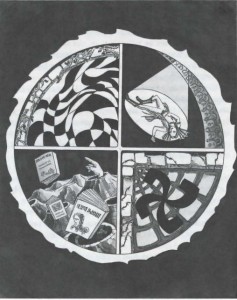

The central image of the Mindwheel itself is one that also appears in “The Figured Wheel,” a poem Pinsky published almost contemporaneously with the game. It’s another element that has continued to recur in Pinsky’s later work.

Imagine a wheel — a colossal, rotating wheel into which is drawn all of the images of a culture: every experience, every event, every object, every person’s mind and body. This wheel is a vortex which you must try to manipulate and understand.

It involves the idea of striving for control and mastery, and the world being so complicated that every time you strive you’re creating another system that becomes part of this big whirling thing which is everything everybody’s ever known or thought or dreamed up to amuse themselves. Jokes and technologies and mythologies and religions and roads and… just everything.

Such heady concepts aside, the question of what Mindwheel ultimately all means is a fraught one. There’s a telling moment near the end of the game where in order to progress you have to cold-bloodedly sacrifice a certain frog who’s been your loyal companion through most of the game. Trinity, Brian Moriarty’s masterpiece which we’ll be getting to in a future article, has a similar moment which is among its most moving and important, serving as a critique of the whole atomic doctrine of mutually assured destruction and the idea of sacrificing the few for the needs of the many which led to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Before you rush to comment, do know that the decision to drop those bombs is one with which I must unhappily agree.) But then Trinity is a work with some very clear messages to impart. In Mindwheel the sacrifice is played almost for laughs; the frog returns in the finale as a happy zombie.

Does this make Mindwheel a lesser work than Trinity? Well, it certainly takes itself less seriously, but we need not condemn it for that. There was a time when poets would compete to do their patrons proud by taking a well-known vignette out of the Bible or mythology and embellishing it over hundreds or thousands of lines of verse, adding layer after layer of pathos and sensuality and imaginative gilding, like a literary version of a guitar-shredding contest; see Shakespeare’s “Venus and Adonis” and “The Rape of Lucrece” for spectacular examples of the genre. There’s some of that same spirit to Mindwheel. Pinsky is having fun here. Poetry should be, whatever else it is, fun.

Pinsky was never more delighted by Mindwheel than when it managed to surprise him, which it did more often than you might expect thanks to the rather loosy-goosy and free-association-inclined BTZ parser.

I was playing the game with my fifteen-year-old son, and we got up a tree. There was a lizard at the base of the tree that would repeatedly kill us. I knew that it was random, but we were on a bad run. We also had our friend the frog with us in the tree. So we gave the disk to the frog and said, “Frog, go down and kill the lizard.” By God, he did it. And the message appeared that the lizard died spewing blood and pus. The creators of the game didn’t know what was going to happen.

One of his favorite anecdotes is that of the beautiful lady to which a friend typed, “You look like my mother.” “I will look the way you want me to” was her alleged reply. (Unfortunately, the published version of the game yields the far less satisfying “Okay, I’ll look.” The problem with a parser like Synapse’s is that it might deliver something unexpected and brilliant from time to time in response to some unusual input, but nine times out of ten it just delivers gibberish or takes your command as meaning something that you really, really didn’t want to do.)

The period of Mindwheel‘s development was a happy and fulfilling one for Pinsky, but a difficult one for Synapse. In addition to the Electronic Novel line, the company had just launched another bold new initiative: to develop a line of business applications — SynFile, SynCalc, and SynTrend — to be marketed and distributed by Atari themselves. In July of 1984, however, Jack Tramiel bought Atari (a story we’ll be getting to in detail in a future article), and promptly told Synapse that he didn’t want their applications and didn’t intend to pay for them. Synapse, who had invested heavily in the work, became just the latest of a long line of Tramiel suppliers to be double-crossed and financially destroyed by the old business warrior. Meanwhile the rest of the Atari 8-bit market, still Synapse’s bread and butter, was in increasingly dire straits, being pummeled by the Commodore 64. Flying high barely six months before, Synapse suddenly faced bankruptcy before they could release a single one of the Electronic Novels that they hoped would stake out for them a new place in the industry. A savior appeared in the form of Brøderbund, who agreed to buy Synapse and take them under their wing in October. The Carlstons knew and liked Wolosenko and the rest of the Synapse folks, and wanted their expertise in action-game programming as well as the promising Electronic Novel line; it was still the era of bookware, after all, with Infocom’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy the talk of the industry.

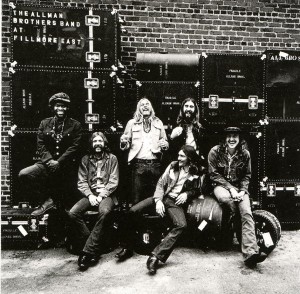

The release date for Mindwheel slipped a bit amidst all the chaos, from the planned late 1984 to February of 1985. It generated the last big wave of the already dying bookware storm, with some images that can seem as surreal today as anything in the game proper: Pinsky blinking amidst the strobe lights at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show; Pinsky waxing philosophical in those noted literary magazines Compute!’s Gazette and A.N.A.L.O.G. (“The #1 Magazine for Atari Computer Owners!”). It’s questionable, though, to what degree the press buzz translated into sales, although Mindwheel undoubtedly became by far the best selling of the Electronic Novel line as a whole — not, alas, a high bar to clear.

I’ve long since made my peace with the fact that traditional parser-driven interactive fiction is, due to various irresistible forces, just an intriguing blip in the histories of literature and/or gaming (take your pick) that will quite likely die entirely with my generation. In general, I think that’s fine; Shakespeare is still as beautiful and relevant as ever despite the fact that modern theater has as little in common with the Elizabethan stage as does textual interactive fiction with a modern graphical game. Certainly elaborate counter-factuals, whether in life or in history, are seldom all that productive. Yet it’s hard not to feel just a little bit wistful reading those old interviews with Pinsky where he throws out ideas of what he’d like to try in his next game whenever someone “asks me to do another of these”; wistful for that world, widely accepted as inevitable for a brief instant in the mid-1980s, when major writers — good writers — would be routinely asked whether their next work would be interactive or non-interactive.

Ah, well, at least we have Mindwheel. The Apple II version I’m providing for download here is probably your best bet, being very playable and also quite easy to get up and running in any number of slick Apple II emulators like AppleWin; be sure to answer “yes” to 80 columns and to turn on faster disk-drive emulation. It’s worth the effort. (Edit: Steve Hales has now made a web page that hosts Mindwheel for play online in a browser. You unfortunately can’t save, but this is by far the easiest way to get a taste of the experience.) Whatever the reasons for Mindwheel‘s academic reputation today, it’s definitely not undeserved.

(This article draws heavily from Jason Scott’s interview with the ever thoughtful and articulate Robert Pinsky for Get Lamp. Magazine sources this time were: A.N.T.I.C. of April 1983, November 1984, and July 1985; Ahoy! of February 1984; Compute!’s Gazette of June 1985; Analog of December 1985; QuestBusters of March 1985. There’s an interesting discussion of Mindwheel in Nick Montfort’s Twisty Little Passages and also in an article Pinsky himself wrote for the Autumn 1987 New England Review. Finally, Steve Hales’s brief recollections of working with Pinsky can be found in two places online.)