Just as the Ultima Online beta test was beginning, Electronic Arts was initiating the final phase of its slow-motion takeover of Origin Systems. In June of 1997, the mother ship in California sent down two Vice Presidents to take over completely in Texas, integrate Origin well and truly into the EA machine, and end once and for all any semblance of independence for the studio. Neil Young became Origin’s new General Manager on behalf of EA, while Chris Yates became Chief Technical Officer. Both men were industry veterans.

Appropriately enough given that he was about to become the last word on virtual Britannia, Neil Young was himself British. He attributes his career choice to the infamously awful English weather. “There are a lot of people in the games industry that come from the UK,” he says. “I think it’s because the weather is so bad that you don’t have a lot to do, so you either go into a band or teach yourself to program.” He chose the latter course at a time when computer games in Britain were still being sold on cassette tape for a couple of quid. After deciding to forgo university in favor of a programming job at a tiny studio called Imagitec Design in 1988, he “quickly realized there were more gifted engineers,” as he puts it, and “moved into producing.” Having made a name for himself in that role, he was lured to the United States by Virgin Interactive in 1992, then moved on to EA five years later, which organization had hand-picked him for the task of whipping its sometimes wayward and lackadaisical stepchild Origin into fighting shape.

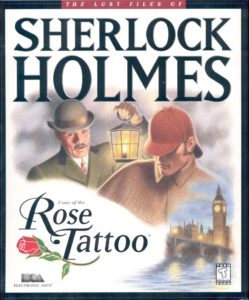

Chris Yates had grown up amidst the opposite of English rain, hailing as he did from the desert gambler’s paradise Las Vegas. He was hired by the hometown studio Westwood Associates in 1988, where he worked as a programmer on games like Eye of the Beholder, Dune II, and Lands of Lore. In 1994, two years after Virgin acquired Westwood, he moved to Los Angeles to join the parent company. There he and Young became close friends as well as colleagues, such that they chose to go to EA together as a unit.

The two were so attractive to EA thanks not least to an unusual project which had occupied some of their time during their last year and a half or so at Virgin. Inspired by Air Warrior, the pioneering massively-multiplayer online flight simulator that had been running on the GEnie commercial online service since the late 1980s, a Virgin programmer named Rod Humble proposed in 1995 that his company invest in something similar, but also a bit simpler and more accessible: a massively-multiplayer version of Asteroids, the 1979 arcade classic whose roots stretched all the way back to Spacewar!, that urtext of videogaming. Neil Young and his friend Chris Yates went to bat for the project: Young making the business case for it as an important experiment that could lead to big windfalls later on, Yates pitching in to offer his exceptional technical expertise whenever necessary. Humble and a colleague named Jeff Paterson completed an alpha version of the game they called SubSpace in time to put it up on the Internet for an invitation-only testing round in December of 1995. Three months later, the server was opened to anyone who cared to download the client — still officially described as a beta version — and have at it.

SubSpace was obviously a very different proposition from the likes of Ultima Online, but it fits in perfectly with this series’s broader interest in persistent online multiplayer gaming (or POMG as I’ve perhaps not so helpfully shortened it). For, make no mistake, the quality of persistence was as key to its appeal as it was to that of such earlier featured players in this series as Kali or Battle.net. SubSpace spawned squads and leagues and zones; it became an entire subculture unto itself, one that lived in and around the actual battles in space. The distinction between it and the games of Kali and Battle.net was that SubSpace was massively — or at least bigly — multiplayer. Whereas an online Diablo session was limited to four participants, SubSpace supported battles involving up to 250 players, sometimes indulging in crazy free-for-alls, more often sorted into two or more teams, each of them flying and fighting in close coordination. It thus quickly transcended Asteroids in its tactical dimensions as well as its social aspects — transcended even other deceptively complex games with the same roots, such as Toys for Bobs’s cult classic Star Control. That it was playable at all over dial-up modem connections was remarkable; that it was so much fun to play and then to hang out in afterward, talking shop and taking stock, struck many of the thousands of players who stumbled across it as miraculous; that it was completely free for a good long time was the icing on the cake.

It remained that way because Virgin didn’t really know what else to do with it. When the few months that had been allocated to the beta test were about to run out, the fans raised such a hue and cry that Virgin gave in and left it up. And so the alleged beta test continued for more than a year, the happy beneficiary of corporate indecision. In one of his last acts before leaving Virgin, Neil Young managed to broker a sponsorship deal with Pepsi Cola, which gave SubSpace some actual advertising and another lease on life as a free-to-play game. During that memorable summer of the Ultima Online beta test, SubSpace was enjoying what one fan history calls its “greatest days” of all: “The population tripled in three months, and now there were easily 1500-plus people playing during peak times.”

With the Pepsi deal about to run out, Virgin finally took SubSpace fully commercial in October of 1997, again just as Ultima Online was doing the same. Alas, it didn’t go so well for SubSpace. Virgin released it as a boxed retail game, with the promise that, once customers had plunked down the cash to buy it, access would be free in perpetuity. This didn’t prevent half or more of the existing user base from leaving the community, even as nowhere near enough new players joined to replace them. Virgin shut down the server in November of 1998; “in perpetuity” had turned out to be a much shorter span of time than anyone had anticipated.

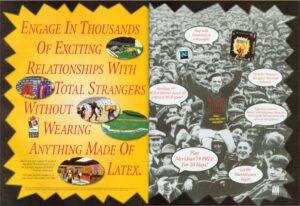

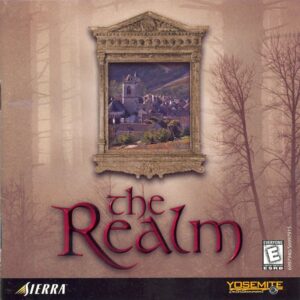

As we’ve seen before in this series, however, the remaining hardcore SubSpace fans simply refused to let their community die. They put up their own servers — Virgin had made the mistake of putting all the code you needed to do so on the same disc as the client — and kept right on space-warring. You can still play SubSpace today, just as you can Meridian 59 and The Realm. A website dedicated to tracking the game’s “population statistics” estimated in 2015 that the community still had between 2000 and 3000 active members, of whom around 300 might be online at any given time; assuming these numbers are to be trusted, a bit of math reveals that those who like the game must really like it, spending 10 percent or more of their lives in it. That same year, fans put their latest version of the game, now known as Subspace Continuum, onto Steam for free. Meanwhile its original father Rod Humble has gone on to a long and fruitful career in POMG, working on Everquest, The Sims Online, and Second Life among other projects.

But we should return now to the summer of 1997 and to Origin Systems, to which Neil Young and Chris Yates came as some of the few people in existence who could boast not only of ideas about POMG but of genuine commercial experience in the field, thanks to SubSpace. EA hoped this experience would serve them well when it came to Ultima Online.

Which isn’t to say that the latter was the only thing they had on their plates: the sheer diversity of Young’s portfolio as an EA general manager reflects the confusion about what Origin’s identity as a studio should be going forward. There were of course the two perennials, Ultima — meaning for the moment at least Ultima Online — and Wing Commander, which was, as Young says today, “a little lost as a product.” Wing Commander, the franchise in computer gaming during the years immediately prior to DOOM, was becoming a monstrous anachronism by 1997. Shortly after the arrival of Young and Yates, Origin would release Wing Commander: Prophecy, whose lack of the Roman numeral “V” that one expected to see in its name reflected a desire for a fresh start on a more sustainable model in this post-Chris Roberts era, with a more modest budget to go along with more modest cinematic ambitions. But instead of heralding the dawn of a new era, it would prove the franchise’s swan song; it and its 1998 expansion pack would be the last new Wing Commander computer games ever. Their intended follow-up, a third game in the Wing Commander: Privateer spinoff series of more free-form outer-space adventures, would be cancelled.

In addition to Ultima and Wing Commander, EA had chosen to bring under the Origin umbrella two product lines that were nothing like the games for which the studio had always been known. One was a line of military simulations that bore the imprimatur of “Jane’s,” a print publisher which had been the source since the turn of the twentieth century of the definitive encyclopedias of military hardware of all types. The Jane’s simulations were overseen by one Andy Hollis, who had begun making games of this type for MicroProse back in the early 1980s. The other line involved another MicroProse alum — in fact, none other than Sid Meier, whose name had entered the lexicon of many a gaming household by serving as the prefix before such titles as Pirates!, Railroad Tycoon, Civilization, and Colonization. Meier and two other MicroProse veterans had just set up a studio of their own, known as Firaxis Games, with a substantial investment from EA, who planned to release their products under the Origin Systems label. Origin was becoming, in other words, EA’s home for all of its games that were made first and usually exclusively for computers rather than for the consoles that now provided the large majority of EA’s revenues; the studio had, it seemed, more value in the eyes of the EA executive suite as a brand than as a working collective.

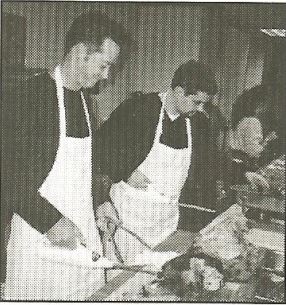

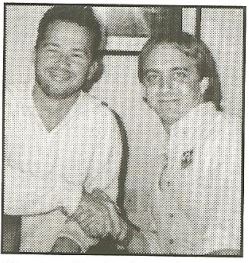

Still, this final stage of the transition from independent subsidiary to branch office certainly could have been even more painful than it was. Neil Young and Chris Yates were fully aware of how their arrival would be seen down in Austin, and did everything they could to be good sports and fit into the office culture. Brit-in-Texas Young was the first to come with the fish-out-of-water jokes at his own expense — “I was expecting a flat terrain with lots of cowboys, cacti, and horses, so I was pleasantly surprised,” he said of Austin — and both men rolled up their sleeves alongside Richard Garriott to serve the rest of the company a turkey dinner at Thanksgiving, a longtime Origin tradition.

Young and Yates had received instructions from above that Ultima Online absolutely had to ship by the end of September. Rather than cracking the whip, they tried to cajole and josh their way to that milestone as much as possible. They agreed to attend the release party in drag if the deadline was met; then Young went one step farther, promising Starr Long a kiss on the lips. Yates didn’t go that far, but he did agree to grow a beard to commemorate the occasion, even as Richard Garriott, whose upper lip hadn’t seen the sun since he’d graduated from high school, agreed to shave his.

Young and Yates got it done, earning for themselves the status of, if not the unsung heroes of Ultima Online, two among a larger group of same. The core group of ex-MUDders whose dream and love Ultima Online had always been could probably have kept running beta tests for years to come, had not these outsiders stepped in to set the technical agenda. “That meant trading off features with technology choices and decisions every minute of the day,” says Young. He brought in one Rich Vogel, who had set up and run the server infrastructure for Meridian 59 at The 3DO Company, to do the same for Ultima Online. In transforming Origin Systems into a maintainer of servers and a seller of subscriptions, he foreshadowed a transition that would eventually come to the games industry in general, from games as boxed products to gaming as a service. These tasks did not involve the sexy, philosophically stimulating ideas about virtual worlds and societies with which Raph Koster and his closest colleagues spent their time and which will always capture the lion’s share of the attention in articles like this one, but the work was no less essential for all that, and no less of a paradigm shift in its way.

So, the big day came and the deadline was met: Ultima Online shipped on September 24, 1997, three days before Meridian 59 would celebrate its first anniversary. The sleek black box was an end and a beginning at the same time. Young and Yates did their drag show, Starr Long got his kiss, and, most shockingly of all, Richard Garriott revealed his naked upper lip to all and sundry. (Opinions were divided as to whether the mangy stubble which Chris Yates deigned to grow before picking up his razor again really qualified as a beard or not.) And then everyone waited to see what would happen next.

EA made and shipped to stores all over the country 50,000 copies of Ultima Online, accompanying it with a marketing campaign that was, as Wired magazine described it, of “Hollywood proportions.” The virtual world garnered attention everywhere, from CNN to The New York Times. These mainstream organs covered it breathlessly as the latest harbinger of humanity’s inevitable cyber-future, simultaneously bracing and unnerving. Flailing about for a way to convey some sense of the virtual world’s scope, The New York Times noted that it would take 38,000 computer monitors — enough to fill a football field — to display it in its entirety at one time. Needless to say, the William Gibson quotes, all “collective hallucinations” and the like, flew thick and fast, as they always did to mark events like this one.

Three weeks after the launch, 38,000 copies of Ultima Online had been sold and EA was spooling up the production line again to make another 65,000. Sales would hit the 100,000 mark within three months of the release. Such numbers were more than gratifying. EA knew that 100,000 copies sold of this game ought to be worth far more to its bottom line than 100,000 copies of any other game would have been, given that each retail sale hopefully represented only the down payment on a long-running subscription at $10 per month. For its publisher, Ultima Online would be the gift that kept on giving.

In another sense, however, the sales figures were a problem. When Ultima Online went officially live, it did so on just three shards: the Atlantic and Pacific shards from the beta test, plus a new Great Lakes one to handle the middle of the country. Origin was left scrambling to open more to meet the deluge of subscribers. Lake Superior came up on October 3, Baja on October 10, Chesapeake on October 16, Napa Valley on November 14, Sonoma on December 13, Catskills on December 22. And still it wasn’t enough.

Origin’s estimates of how many players a single server could reliably support proved predictably overoptimistic. But rather than dial back on the number of players they allowed inside, thereby ensuring that each of them who did get in could have a reasonably enjoyable experience, they kept trying to cover the gap between technical theory and reality by hacking their code on the fly. As a result, Ultima Online became simultaneously the most loved and most hated game in the country. When it all came together, it was magic for many of its players. But truth be told, that didn’t happen anywhere near as often as one might have wished in that first year or so. Extreme lag, inexplicable glitches, dropped connections, and even total server crashes were the more typical order of the day. Of course, with almost everyone who surfed the Web still relying on dial-up modems running over wires that had been designed to carry voices rather than computer data, slowdowns and dropped connections were a reality of daily online life even for those who weren’t attempting to log onto virtual worlds. This created a veneer of plausible deniability, which Origin’s tech-support people, for lack of any other suggestions or excuses to offer, leaned on perhaps a bit too heavily. After all, who could say for sure that the problem any individual player might be having wasn’t downstream from Origin’s poor overtaxed server?

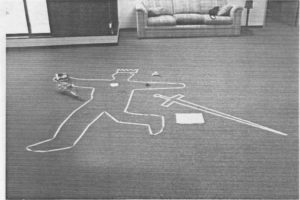

Weaselly excuses like these led to the first great act of civil disobedience by the residents of Britannia, just a few weeks after the launch, when hundreds of players gathered outside Lord British’s castle, stripped themselves naked, broke into the throne room, drank gallons of wine, and proceeded to disgorge all of it onto Richard Garriott’s virtual furniture, whilst chanting in unison their demands for a better, stabler virtual world. The world’s makers were appalled, but also weirdly gratified. What better sign of a budding civic life could there be than a full-on political protest? “We were all watching and thinking it was a grand statement about the project,” says Richard Garriott. “As unhappy as they were about the game, they voiced their unhappiness in the context of the game.” Much of what happened inside Ultima Online during the first year especially had the same quality of being amazing for philosophers of virtual worlds to witness, but stressful for the practical administrators who were trying to turn this one into a sustainable money tree. The rub was that the two categories were combined in the very same people, who were left feeling conflicted to say the least.

The journals of hardcore gaming, hardly known for their stoicism in the face of hype on most days, were ironically more reserved and skeptical than the mainstream press on the subject of Ultima Online, perchance because they were viewing the virtual world less as a harbinger of some collective cyber-future and more as a game that their readers might wish to, you know, actually play. Computer Gaming World wittily titled its scathing review, buried on page 162 and completely unmentioned on the cover of the issue in question, simply “Uh-Oh.” Among the litany of complaints were “numerous and never-ending bugs, horrible lag time, design issues [that] lead to repetitive and time-consuming activities, and [an] unbalanced economy.” The magazine did admit that “Ultima Online could become a truly great game. But we can’t review potential, we can only review concrete product.” Editor-in-chief Johnny L. Wilson, for his part, held out little hope for improvement. “Ultima Online begins with hubris and ends in Greek tragedy,” he said. “The hubris is a result of being unwilling to learn from others’ mistakes. The tragedy is that it could have been so much more.” Randy Farmer, co-creator of the earlier would-be virtual world Habitat, expressed a similar sentiment, saying that “Origin seems to have ignored many of the lessons that our industry has learned in the last ten years of building online worlds. They’re making the same mistakes that first-time virtual-world builders always make.”

The constant crashes and long periods of unexplained down time associated with a service for which people were paying good money constituted a corporate lawyer’s worst nightmare — or a different sort of lawyer’s wet dream. One of these latter named George Schultz began collecting signatures from Origin’s most disgruntled customers within weeks, filing a class-action lawsuit in San Diego at the beginning of March of 1998. Exhibit A was the copy right there on the back of the box, promising “a living, growing world where thousands of real people discover real fantasy and adventure, 24 hours a day, every day of the year,” with all of it taking place “in real time.” This was, claimed Schultz, a blatant case of false advertising. “We’re not trying to tell anyone how to design a good or a bad game,” he said. “What it’s about is holding Origin and EA to the promises they made on the box, in their advertising, and [in] the manual. It’s about the misrepresentations they’ve made. A big problem with the gaming industry is that they think there are some special rules that only apply to them.”

Whatever the truth of that last claim, there was no denying that just about half of the learning curve of Ultima Online was learning to navigate around the countless bugs and technical quirks. For example, Origin took down each shard once per day for a backup and a “therapeutic” reboot that was itself a testament to just what a shaky edifice the software and hardware were. When the server came back up again, it restored the state of the world from the last backup. But said state was a snapshot in time from one hour before the server went down. There was, in other words, an hour every day during which everything you did in virtual Britannia was doomed to be lost; this was obviously not a time to go on any epic, treasure- and experience-point-rich adventures. Yet such things were documented nowhere; one learned them only through the proverbial school of hard knocks.

In their defense, Origin was sailing into completely uncharted waters with Ultima Online. Although there had been online virtual worlds before, dating all the way back to that first MUD of 1978 or 1979, none of them — no, not even Meridian 59 and The Realm — had been as expansive, sophisticated, and most of all popular as these shards of Britannia. Most of the hardware technologies that would give rise to the era of Web 2.0, from DSL in homes to VPS’s in data centers, existed only as blueprints; ditto most of the software. No one had ever made a computer game before that required this much care and feeding after the initial sale. And it wasn’t as if the group entrusted with maintaining the beast was a large one. Almost the entirety of the Ultima IX team which had been parachuted in six months before the launch to just get the world done already was pulled out just as abruptly as soon as it started accepting paying subscribers, leaving behind a crew of maintainers that was little bigger than the original team of ex-MUDders who had labored in obscurity for so long before catching the eye of EA’s management. The idea that maintaining a virtual world might require almost as much manpower and ongoing creative effort as making it in the first place was too high a mental hurdle for even otherwise clever folks like Neil Young and Chris Yates to clear at this point.

Overwhelmed as they were, the maintainers began to rely heavily on unpaid volunteers from the community of players to do much of the day-to-day work of administrating the world, just as was the practice on MUDs. But Ultima Online ran on a vastly larger scale than even the most elaborate MUDs, making it hard to keep tabs on these volunteer overseers. While some were godsends, putting in hours of labor every week to make Britannia a better place for their fellow players, others were corrupted by their powers, manipulating the levers they had to hand to benefit their friends and punish their enemies. Then, too, the volunteer system was another legal quagmire, one that would doubtless have sent EA’s lawyers running screaming from the room if anyone had bothered to ask them about it before it was rolled out; sure enough, it would eventually lead to another lawsuit, this one more extended, serious, and damaging than the first.

In the meanwhile, though, most players did not rally behind the first lawsuit to anything like the degree that George Schultz might have been hoping. The fact was that even the ones who had vomited all over Lord British’s throne had done so because they loved their virtual Britannia and wanted to see it fixed rather than destroyed, as it would likely be if Schultz won the day. The suit concluded in a settlement at the end of 1998. The biggest concession on the part of the defendants was a rather weird one that gave no recompense to any individual inhabitant of virtual Britannia: EA agreed to donate $15,000 to the San Jose Tech Museum of Innovation. Perhaps Schultz thought that it would be able to innovate up a more reliable virtual world.

While many of the technical problems that beset Ultima Online were only to be expected in the context of the times, some of the other obstacles to enjoying the virtual world were more puzzling. First and foremost among these was the ever-present issue of players killing other players, which created so much frustration that George Schultz felt compelled to explicitly wall it off from the breach-of-trust claims that were the basis of his lawsuit: “We’re not getting into whether there should be player-killing.” Given that it had been such a constant theme of life (and death) in virtual Britannia going all the way back to the alpha-testing phase, the MUDders might have taken more steps to address it before the launch. As it was, though, one senses that, having seen so many of their ideas about a virtual ecology and the like not survive contact with real players, having been forced to give up in so many ways on virtual Britannia as a truly self-sustaining, living world, they were determined to make this the scene of their last stand, the hill that they would either hold onto or die trying.

Their great white hope was still the one that Richard Garriott had been voicing in interviews since well before the world’s commercial debut: that purely social pressures would act as a constraint on player-killing — that, in short, their world would learn to police itself. In fact, the presence of player-killing might act as a spur to civilization — for, as Raph Koster said, “cultures define and refine themselves through conflict.” They kept trying to implement systems that would nudge this particular culture in the right direction. They decided that, after committing murder five times, a player would be branded with literal scarlet letters: the color of his onscreen name would change from blue to red. Hopefully this would make him a pariah among his peers, while also making it very dangerous for him to enter a town, whose invulnerable computer-controlled guards would attack him on sight. The designers didn’t reckon with the fact that a virtual life is, no matter how much they might wish otherwise, simply not the same as a real life. Some percentage of players, presumably perfectly mild-mannered and law-abiding in the real world, reveled in the role of murderous outlaws online, taking the red letters of their name as a badge of honor rather than shame, the dangers of the cities as a challenge rather than a deterrent. To sneak past the city gates, creep up behind an unsuspecting newbie and stab her in the back, then get out of Dodge before the city watch appeared… now, that was good times. The most-wanted rolls posted outside the guard stations of Britannia became, says Raph Koster, “a high-score table for player killers.”

The MUDders’ stubborn inflexibility on this issue — an issue that was by all indications soon costing Ultima Online large numbers of customers — was made all the more inexplicable in the opinion of many players by the fact that it was, in marked contrast to so many of the other problems, almost trivial to address in programming terms. An “invulnerability” flag had long existed, to be applied not only to computer-controlled city guards but to special human-controlled personages such as Lord British to whom the normal laws of virtual time and space did not apply. All Origin had to do was add a few lines of code to automatically turn the flag on when a player walked into designated “safe” spaces. That way, you could have places where those who had signed up mostly in order to socialize could hang out without having to constantly look over their backs, along with other places where the hardcore pugilists could pummel one another to their heart’s content. Everyone would be catered to. Problem solved.

But Raph Koster and company refused to take this blindingly obvious step, having gotten it into their heads that to do so would be to betray their most cherished ideals. They kept tinkering around the edges of the problem, looking for a subtler solution that would preserve their world’s simulational autonomy. For example, they implemented a sort of karmic justice system, which dictated that players who had been evil during life would be resurrected after death only after losing a portion of their stats and skills. Inevitably, the player killers just took this as another challenge. Just don’t get killed, and you would never have to worry about it.

The end result was to leave the experience of tens of thousands of players in the unworthy hands of a relatively small minority of “griefers,” people who thrived on causing others pain and distress. Like all bullies, they preyed on the weak; their typical victims were the newbies, unschooled in the ways of defense, guiding characters with underwhelming statistics and no arms or armor to speak of. Such new players were, of course, the ones whose level of engagement with the game was most tentative, who were the mostly likely to just throw up their hands and go find something else to play after they’d been victimized once or twice, depriving Origin of potentially hundreds of dollars in future subscription revenue.

In light of this, it’s strange that no one from EA or Origin overrode the MUDders on this point. For his part, Richard Garriott was adamantly on their side, insisting that Ultima Online simply had to allow player-killing if it wasn’t to become a mockery of itself. It was up to the dissatisfied and victimized residents themselves to band together and turn Britannia into the type of world they wanted to live in; it wasn’t up to Origin to step in and fix their problems for them with a deus ex machina. “When we first launched Ultima Online, we set out to create a world that supported the evil player as a legitimate role,” said Garriott in his rather high-handed way. “Those who have truly learned the lessons of the [single-player] Ultima games should cease their complaining, rise to the challenge, and make Britannia into the place they want it to be.” He liked to tell a story on this subject. (Knowing Garriott’s penchant for embellishment, it probably didn’t happen, or at least didn’t happen quite like this. But that’s not relevant to its importance as allegory.)

One evening, he was wandering the streets of the capital in his Lord British persona, when he heard a woman screaming. Rushing over to her, he was told that a thief had stolen all of her possessions. His spirit of chivalry was awoken; he told her that he would get her things back for her. Together they tracked down the thief and cornered him in a back alley. Lord British demanded that the thief return the stolen goods, and the thief complied. They all went their separate ways. A moment later, the woman cried out again; the thief had done it again.

This time, Lord British froze the thief with a spell before he could leave the scene of the crime. “I told you not to do that,” he scolded. “What are you doing?”

“Sorry, I won’t do it again,” said the thief as he turned over the goods for a second time.

“If you do that again, I’m going to ban you from the game,” said Lord British.

You might be able to guess what happened next: the thief did it yet again. “I said I was going to ban you, and now I have to,” shouted Lord British, now well and truly incensed. “What’s wrong with you? I told you not to steal from this woman!”

The thief’s answer stopped Garriott in his tracks. “Listen. You created this world, and I’m a thief,” he said, breaking character for the first time. “I steal. That’s what I do. And now you’re going to ban me from the game for playing the role I’m supposed to play? I lied to you before because I’m a thief. The king caught me and told me not to steal. What am I going to do, tell you that as soon as you turn around I’m going to steal again? No! I’m going to lie.”

And Garriott realized that the thief was right. Garriott could do whatever he wished to him as Lord British, the reigning monarch of this world. But if he wished to stay true to all the things he had said in the past about what virtual Britannia was and ought to be, he couldn’t go outside the world to punish him as Richard Garriott, the god of the server looking down from on-high.

Some of the questions with which Origin was wrestling resonate all too well today: questions involving the appropriate limits of online free speech — or rather free action, in this case. They are questions with which everyone who has ever opened an Internet discussion up to the public, myself included, have had to engage. When does strongly felt disagreement spill over into bad faith, counterpoint into disruption for the sake of it? And what should we do about it when it does? In Origin’s case, the pivotal philosophical question at hand was where the boundary lay between playing an evil character in good faith in a fantasy world and purposely, willfully trying to cause real pain to other real people sitting behind other real computers. Origin had chosen to embrace a position close to the ground staked out by our self-described “free-speech maximalists” of today. And like them, Origin was learning that the issue is more dangerously nuanced than they had wished to believe.

But there were others sorts of disconnect at play here as well. Garriott’s stern commandment that his world’s inhabitants should “cease their complaining, rise to the challenge, and make Britannia into the place they want it to be” becomes more than a bit rich when we remember that it was being directed toward Origin’s paying customers. Many of them might have replied that it was up to Origin rather than they themselves to make Britannia a place they wanted to be, lest they choose to spend their $10 per month on something else. The living-world dynamic held “as long as everyone is playing the same game,” wrote Amy Jo Kim in an article about Ultima Online and its increasingly vocalized discontents that appeared in Wired magazine in the spring of 1998. “But what happens when players who think they’re attending an online Renaissance Faire find themselves at the mercy of a violent, abusive gang of thugs? In today’s Britannia, it’s not uncommon to stumble across groups of evil players who talk like Snoop Doggy Dogg, dress like gangstas, and act like rampaging punks.” To be sure, some players were fully onboard with the “living-world” policy of (non-)administration. Others, however, had thought, reasonably enough given what they had read on the back of the game’s box, that they were just buying an entertainment product, a place to hang out in a few hours per day or week and have fun, chatting and exploring and killing monsters. They hadn’t signed up to organize police forces or lead political rallies. Nor had they signed up to be the guinea pigs in some highfalutin social experiment. No; they had signed up to play a game.

As it was, Ultima Online was all but impossible to play casually, thanks not only to the murderers skulking in its every nook and cranny but to core systems of the simulation itself. For example, if you saved up until you could afford to build yourself a nice little house, made it just like you wanted it, then failed to log on for a few days, when you did return you’d find that your home had disappeared, razed to make room for some other, more active player to build something. Systems like these pushed players to spend more time online as a prerequisite to having fun when they were there. Some left when the demands of the game conflicted with those of real life, which was certainly the wisest choice. But some others began to spend far more time in virtual Britannia than was really good for them, raising the specter of gaming addiction, a psychological and sociological problem that would only become more prevalent in the post-millennial age.

Origin estimated that the median hardcore player spent a stunning if not vaguely horrifying total of six hours per day in the virtual world. And if the truth be told, many of the non-murderous things with which they were expected to fill those hours do seem kind of boring on the face of it. This is the flip side of making a virtual world that is more “realistic”: most people play games to escape from reality for a while, not to reenact it. With all due respect to our dedicated and talented real-world tailors and bakers, most people don’t dream of spending their free time doing such jobs online. Small wonder so many became player killers instead; at least doing that was exciting and, for some people at any rate, fun. From Amy Jo Kim’s article:

There’s no shortage of realism in this game — the trouble is, many of the nonviolent activities in Ultima Online are realistic to the point of numbingly lifelike boredom. If you choose to be a tailor, you can make a passable living at it, but only after untold hours of repetitive sewing. And there’s no moral incentive for choosing tailoring — or any honorable, upstanding vocation, for that matter. So why be a tailor? In fact, why not prey on the tailors?

True, Ultima Online is many things to many people. Habitués of online salons come looking for intellectual sparring and verbal repartee. Some other people log on in search of intimate but anonymous social relationships. Still others play the game with cunning yet also a discernible amount of self-restraint, getting rich while staying pretty honest. But there’s no avoiding where the real action is: an ever-growing number are playing Ultima Online to kill everything that moves.

All of this had an effect: all signs are that, after the first rush of sales and subscriptions, Ultima Online began to stagnate, mired in bad reviews, ongoing technical problems, and a growing disenchantment with the player-killing and the other barriers to casual fun. Raph Koster admits that “our subscriber numbers, while stratospheric for the day, weren’t keeping up” with sales of the boxed game, because “the losses [of frustrated newbies] were so high.”

Although Origin and EA never published official sales or subscriber numbers, I have found one useful data point from the early days of Ultima Online, in an internal Origin newsletter dated October 30, 1998. As of this date, just after its first anniversary, the game had 90,000 registered users, of whom approximately half logged on on any given day. These numbers are depicted in the article in question as very impressive, as indeed they were in comparison to the likes of Meridian 59 and The Realm. Still, a bit of context never hurts. Ultima Online had sold 100,000 boxed copies in its first three months, yet it didn’t have even that many subscribers after thirteen months, when its total boxed sales were rounding the 200,000 mark. The subscriber-retention rate, in other words, was not great; a lot of those purchased CDs had become coasters in fairly short order.

Nine shards were up in North America at this time, a number that had stayed the same since the previous December. And it’s this number that may be the most telling one of all. It’s true that, since demand was concentrated at certain times of day, Ultima Online was hosting just about all the players it could handle with its current server infrastructure as of October of 1998. But then again, this was by no means all the players it should be able to handle in the abstract: new shards were generally brought into being in response to increasing numbers of subscribers rather than vice versa. The fact that no new North American shards had been opened since December of 1997 becomes very interesting in this light.

I don’t want to overstate my case here: Ultima Online was extremely successful on its own, somewhat experimental terms. We just need to be sure that we understand what those terms were. By no means were its numbers up there with the industry’s biggest hits. As a point of comparison, let’s take Riven, the long-awaited sequel to the mega-hit adventure game Myst. It was released two months after Ultima Online and went on to sell 1 million units in its first year — at least five times the number of boxed entrées to Origin’s virtual world over the same time period, despite being in a genre that was in marked decline in commercial terms. Another, arguably more pertinent point of comparison is Age of Empires, a new entry in the red-hot real-time-strategy genre. Released just one month after Ultima Online, it outsold Origin’s virtual world by more than ten to one over its first year. Judged as a boxed retail game, Ultima Online was a middling performer at best.

Of course, Ultima Online was not just another boxed retail game; the unique thing about it was that each of the 90,000 subscribers it had retained was paying $10 every month, yielding a steady revenue of almost $11 million per year, with none of it having to be shared with any distributor or retailer. That was really, really nice — nice enough to keep Origin’s head above water at a time when the studio didn’t have a whole lot else to point to by way of justifying its ongoing existence to EA. And yet the reality remained that Ultima Online was a niche obsession rather than a mass-market sensation. As so often happens in life, taking the next step forward in commercial terms, not to mention fending off the competition that was soon to appear with budgets and publisher support of which Meridian 59 and The Realm couldn’t have dreamed, would require a degree of compromise with its founding ideals.

Be that as it may, however, one thing at least was now clear: there was real money to be made in the MMORPG space. Shared virtual worlds would soon learn to prioritize entertainment over experimentation. Going forward, there would be less talk about virtual ecologies and societies, and more focus on delivering slickly packaged fun, of the sort that would keep all kinds of players coming back for more — and, most importantly of all, get those subscriber counts rising once more.

I’ll continue to follow the evolution of PMOG, MMORPGs, and Ultima Online in future articles, and maybe see if I can’t invent some more confusing acronyms while I’m at it. But not right away… other subjects beg for attention in the more immediate future.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Braving Britannia: Tales of Life, Love, and Adventure in Ultima Online by Wes Locher, Postmortems: Selected Essays, Volume One by Raph Koster, Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay, Through the Moongate, Part II by Andrea Contato, Explore/Create by Richard Garriott, and MMOs from the Inside Out by Richard Bartle, and Dungeons and Dreamers by Bard King and John Borland. Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of February 20 1998 and October 30 1998; Computer Gaming World of February 1998 and November 1998; New York Times of October 20 1997; Wired of May 1998.

Web sources include a 2018 Game Developers Conference talk by some of the Ultima Online principals, an Ultima Online timeline at UOGuide, and GameSpot‘s vintage reviews of Ultima Online and its first expansion, The Second Age. On the subject of SubSpace, we have histories by Rod Humble and Epinephrine, another vintage GameSpot review, and a Vice article by Emanuel Maiberg.