Shortly before the departure of Peter Langston from the Lucasfilm Games Group, he and Steve Arnold hired one Chip Morningstar as a tools programmer. The latter was coming off a stint spent working for Ted Nelson, a sort of philosopher of information management who had coined the terms “hypertext” and “hypermedia” back in the 1960s. Morningstar, who says that “few people could actually work with Ted for more than a day or two without becoming clinically insane,” was initially thrilled to just hunker down making practical tools for game development on the Games Group’s Unix workstations.

But then, on one of his final days at the office, Langston tried to interest everyone in a joint playthrough of his own old multiplayer grand-strategy classic Empire, for the purpose of, according to Morningstar, “getting us to think about alternative modalities of game design.” They all played for many hours and then, with Langston’s encouragement, picked apart what they liked and didn’t like about the experience. Morningstar found he didn’t much like the very thing that seemingly made Empire a game: the cycle of build-up, increasing conflict, and the final triumph of one player — or, more frequently, the final nuclear annihilation of all of them. He would prefer it if “the world was much bigger and the player goals more open-ended.” He wrote up a proposal for an online portal to host a “10,000-player computer game” that showed the influence of Ted Nelson’s visions of networked consciousness as well as the cyberpunk science fictions that he’d been reading a lot of lately — works like True Names by Vernor Vinge and William Gibson’s brand new, seminal Neuromancer. The poetic language he employed in his proposal rather self-consciously echoes Gibson’s own descriptions of cyberspace.

Picture, if you will, a network, an intricate web of knots and threads spanning thousands of miles. The knots are machines, made of silicon, metal, and plastic. The threads are metal wires. It is a computer network. The machines are computers, sitting in homes, schools, and offices across the continent. The wires are telephone lines, tying the hundreds upon hundreds of individual processors into a single, unified whole. At each of these machines sit people. People of all kinds and all ages… they experience the signs and sounds of that which exists only in the wholeness of the web, and in their own minds.

Steve Arnold made a habit of filing away all of the ideas that poured out of his charges, even seemingly outlandish ones like this one. After all, you never knew what might be worth considering if the right partner and/or situation came along.

We haven’t had much occasion to talk about it yet on this blog, but PCs had always been seen by hackers as, amongst other things, tools of communication. One might even say it was in the PC industry’s very DNA. Well before Apple, for instance, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had gotten their start as businessmen by selling “blue boxes” for purposes of “phone phreaking,” hacking the telephone system to make free long-distance calls. (The widespread application of telecommunications technology to illegal activities would also be an ongoing theme of the young industry.) The first modems were available almost as soon as the first PCs, using hardware designs adapted from bigger institutional computer systems.

To say that using a computer for telecommunications was challenging in the early days hardly begins to describe the situation. “Modem” stands for “modulator/demodulator.” It converts data into sound and transmits it over a phone line, the “modulating” part of the process. What sounds like an unholy racket to human ears can be converted — “demodulated” — back into data that a computer can understand by another modem at the other end of the line. A modem monopolized the phone line, meaning that unless you lived alone or could afford to spring for a second line, negotiations on its use with other householders were likely to be tense ones. Once made, modem connections were notoriously unstable. In many areas even the “call waiting” tone resulting from an incoming call would knock you off the line while simultaneously leaving you no way to answer the second call, a useless double whammy if ever there was one. And Modems were slow. A 300-baud modem, for many years the standard, could transmit or receive at about 35 characters per second, meaning a single line of text on an 80-column screen took well over two seconds to print, a full screen of 25 lines almost a full minute.

Assuming you were willing to put up with all these annoyances, whom should you actually call using your computer? The World Wide Web was still many years in the future, the Internet itself largely restricted to users at big universities and other research institutions, discussing esoteric subjects using specialized messaging software. Your realistic options could thus largely be divided into two categories: the so-called computerized bulletin-board systems, or BBSes, and, in time, bigger commercial dial-up services.

The typical BBS operator was a guy not that different from you who had elected to set up a little online presence with a spare computer — or a primary computer when he wasn’t actually using it — and a second phone line. Since these systems usually only had one modem and one phone line, only one user could actually be online at a time. Accessing a popular system was thus generally a matter of setting up a “war dialer,” a program to dial the BBS’s number again and again until the busy signal was replaced with a modem’s answering tone — all the while, of course, tying up your own phone line with the effort. Once online, you could read and post messages and upload and download software, within reason; you didn’t want to be That Guy staying online for hours and blocking everyone else out of the system. Indeed, popular systems often strictly limited your time to make sure that didn’t happen. Many of the BBSes were engines of software piracy. Thanks to phone phreaking, the necessary numbers and techniques for which were also widely distributed on pirate BBSes, pirates could call systems all over the country and the world, while more legitimate users unwilling to spend a fortune in long-distance fees were limited to those in their own hometowns. BBSes, even — especially! — the legitimate ones, were thus by their very nature very limited affairs, bound to a certain geographic area and, with only 24 hours in a day and only one phone line, sharply restricted in how many users they could realistically support. Many old-timers today will tell you that that was a big part of their charm.

Still, there was obvious potential for larger services that could bring more people together. In the late 1970s one Bill von Meister had an epiphany that would establish the model for such services for many years to come. When corporate America shut down for the evening, he realized, millions of processing hours on time-shared institutional computers went unused, as did much of the telecommunications infrastructure that linked all of those machines together. He founded an online service called The Source to take advantage of this excess capacity by essentially selling it to ordinary computer users at home, who could access his system via modem using local phone numbers that served as entrance ramps to normally business-focused packet-switched networks like Tymnet and Uninet. After The Source was announced at a gala event in June of 1979 — special guest/paid spokesman Isaac Asimov was there to declare it to represent nothing less than “the start of the information age” — similar online services began to spring up in considerable numbers, their user counts to climb steadily. CompuServe, the second entrant in the burgeoning field and always the largest and most lavishly promoted, had 5000 subscribers in 1980; 145,000 in 1984; 300,000 in 1986; 460,000 in 1988.

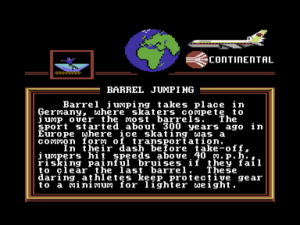

What people did on these services was in some senses mostly the same as what they do on the Internet today. By mid-decade CompuServe offered discussion forums and chat rooms on a huge variety of topics; an online encyclopedia; electronic editions of newspapers and magazines; online banks, stockbrokers, and other financial services; worldwide weather forecasts; online shopping malls, airplane tickets, and hotel reservations; and of course your very own private email address. Games were also popular; amongst the expected slate of traditional board and card games one could find the occasional standout, like CompuServe’s MegaWars, an elaborate and addictive multiplayer strategy game played on a universal scale, not all that far removed from Peter Langston’s Empire. The first accredited online university, called simply The Electronic University, already had 10,000 students by 1985, offering seven degrees from an Associates in the Arts to an MBA. The mainstream media began to publish the occasional skeptical report on a new phenomenon known as “online personals,” noting with shock that some people had supposedly ended up marrying others that they had first met online. Indeed, the amount of sharing that took place online was a constant source of surprise to the unwired. An apocryphal tale made the rounds, winding up eventually even on PBS’s Computer Chronicles program, of a woman who had announced on a chat room that she had had enough, that she was about to kill herself right there and then, only to be talked down from the brink by her interlocutors. Less positively but more inevitably, politicians began to fret about online pornography and child predation, making it an explicit crime to use a computer to traffic in child pornography — it was anyway, but that’s politics for you — with the Child Protection and Obscenity Enforcement Act of 1988.

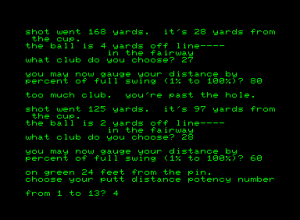

It’s easy enough to see these services, described as I just have in the abstract, as essentially equivalent to the World Wide Web of today. That, however, would be a mistake. I really need to emphasize just how limited and primitive online services of the 1980s were by modern standards. Without the bandwidth to send pictures and with few computers capable of displaying them with any fidelity at all anyway, the online services were made of nothing but text, laboriously transmitted page by page at speeds of 300 or at best 1200 baud. There were no hyperlinks, no mouse support, no color, no sound, no fonts, no page layout, no windows or columns, just walls of slowly printing monospaced monochrome text separated by menu prompts in the form of blinking cursors. And each of these services was a world unto itself: if you signed up for CompuServe, you could only use those facilities that CompuServe offered, could only chat or send mail to other CompuServe subscribers. The interoperability and interconnectedness that define the World Wide Web of today didn’t exist, making your choice of which service to splurge for a fraught one indeed.

Finally, these services were expensive, staggeringly so by modern standards. In 1985 it cost $40 just to sign up with CompuServe, then $6 per hour at 300 baud or $12.50 per hour at 1200 baud during non-business hours. As for usage during business hours, that was so expensive that you didn’t even want to think about it — which was, after all, kind of the point. The other services charged similar rates. Small wonder that avid users devised and shared a multitude of techniques, from command shortcuts for bypassing layers of menus to ways of collecting digests of messages for reading offline, to minimize their time spent connected. And small wonder as well that, despite the services’ steadily increasing user bases, for many years relatively few computer owners had the requisite combination of financial wherewithal and patience to make use of them. At mid-decade it was estimated that less than 5 percent of active home-computer users subscribed to one of the commercial online services, while less than 40 percent of them even owned modems.

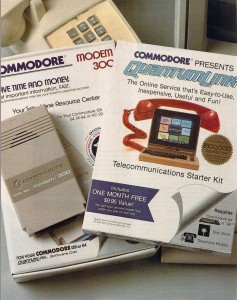

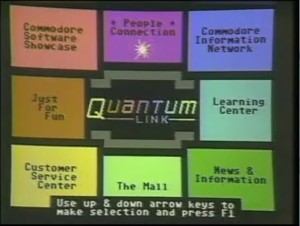

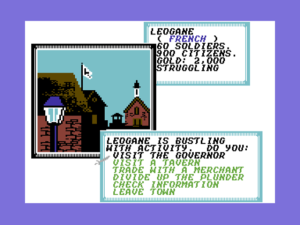

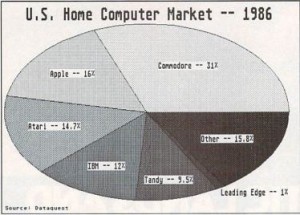

Those numbers represented opportunity. That, anyway, was how they were seen by Steve Case, marketing director for a heretofore underwhelming would-be purveyor of telecommunications services called Quantum Computer Services. Case came up with a scheme that would address some if not all of the reasons that most users still stayed away from the big online services. His QuantumLink would work only on Commodore 64s. Rather than using generic text-oriented terminal software, it would be given away as a user-friendly, colorful, point-and-click-driven application that would nevertheless interface with Quantum’s online databases via modem. And, aware that the Commodore market was the most price-conscious in computing, Case made QuantumLink dramatically cheaper than any other service: a flat fee of $10 per month, plus $3.60 per hour for certain “premium services,” whether delivered at 300 or 1200 baud. The scheme did come with its drawbacks, like the fact that major additions to the service would require the mailing of a new disk to every customer, and of course the fact that it would be limited to Commodore users, but on the whole Case believed the advantages would far outweigh the disadvantages.

Critically, Case was able to convince Commodore themselves to sign on as sponsor and principal investor, making QuantumLink the “official” online service for Commodore owners. QuantumLink “telecommunications starter kits” were soon being inserted into every Commodore modem package, not to mention everywhere else Case could find to stick them. He was determined to make QuantumLink the easier, friendlier online service, suitable for the non-technical. “For the average guy,” he says, “we needed to offer the market something that was a little easier and cheaper and more useful.” Case’s “average guys” would sign up with QuantumLink to the tune of about 50,000 members one year after the service made its debut in November of 1985 — not bad numbers at all for a brand new, platform-specific online service that was starting from scratch.

QuantumLink featured a fairly typical slate of offerings, including plenty of games. The Commodore 64 was after all the premier gaming computer in the country, and the QuantumLink software had actually been built from the remnants of an earlier, failed venture called PlayNet, an attempt to create an online service revolving exclusively around games. QuantumLink’s games were largely inherited from that effort, including old standbys like backgammon, chess, checkers, hangman, and Go, as well as an online casino that dealt in perks rather than money. There were also heaps of public-domain games to download and play offline, plus demo versions of commercial games. Still, right from the outset QuantumLink and Commodore looked for an online game that was newer, bigger, and more exciting, something the likes of which had never been seen before. It was this quest that brought Clive Smith, a vice president of strategic planning at Commodore, out to Lucasfilm Games one day in the summer of 1985, well before the QuantumLink service was planned to actually go live. Smelling a chance to do something unprecedented on someone else’s dime, Steve Arnold pulled Chip Morningstar’s old proposal for a networked virtual world out of his ideas folder. Somewhat to everyone’s surprise, Smith immediately loved it. He quickly secured for Arnold and Morningstar a chance to pitch it in person to Quantum at their headquarters in Vienna, Virginia.

For his presentation, Morningstar dropped all vestiges of an “outer space/conquer the galaxy” type of game like Empire, or for that matter CompuServe’s MegaWars, in favor of a game that “looked kind of funky and suburban,” a “game” in name only that would ultimately be all about “the social dimension — people interacting with other people.” It was an idea so unprecedented that even its originator had difficulty describing or even completely envisioning it. The closest analogues would be MUDs — “multi-user dungeons,” essentially elaborate online text adventures in the spirit of Adventure and Zork that could be occupied by dozens of players at a time. Yet, while there was certainly a strong social element at play there, most MUDs also placed a heavy emphasis on dungeon-crawling, monster-killing, and leveling-up, whilst taking place in exactly the sorts of fantasy or science-fiction worlds that Morningstar had so definitively rejected. And of course MUDs consisted solely of text, while Morningstar’s world was imagined from the start as a richly graphical environment. Groping for the right vocabulary to describe his ideas, he found himself coining new jargon of his own, some of which has persisted to this day. Most notably, he borrowed the term “avatar” from Hinduism, where it represents a deity’s earthly incarnation. Morningstar used it to describe the onscreen figure that each player — the god in the machine, the deity pulling the strings — would control. That said, her avatar wouldn’t quite be her, at least not all the time, for Morningstar’s world would amongst other things be a space for role play, a space for trying new identities on for size. [1]Richard Garriott applied the same term to a game even earlier than Morningstar, during the development of Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, but his usage applies specifically to the ethical quest that forms the plot of that game: the player’s goal is to become an “avatar of virtue.” The more generalized use of the term in videogames is better attributed to Morningstar, even if Garriott’s usage probably better reflects its real implications in Hinduism. Whatever else you could say about “avatar,” it at least sounded more dignified than “puppet.”

The project, first dubbed Universe and then MicroCosm, was a hard sell. For some months Steve Case and the others at Quantum remained intrigued but uncertain. The contract wasn’t finalized and signed at last until December of 1985, after QuantumLink itself was already up and running. By this time the name had been changed yet again, this time to simply Habitat. Hoping to make a splash, the new partners rented the Palladium, the hottest new nightclub in New York City, to officially announce the project in mid-1986, despite the fact that there was still lots of work to be done before it could possibly go live. “It was quite an anomaly to have this essentially hip nightclub where people dressed in black… and then all these computer geeks showing off their multiplayer computer games,” admits Steve Arnold. “It was a little bit of a mismatch between PR positioning and target audience.”

Undaunted, Quantum continued to hype Habitat quite heavily in their advertising. It was perpetually “coming soon,” first in the summer of 1986, then in the fall, then at some undetermined point in 1987. An initial spate of intrigued articles in the Commodore trade press dissipated as the months went by and the project started to look more and more like vaporware. Through it all Chip Morningstar struggled to actually build his monster with the help of a partner, another recent Lucasfilm hire named F. Randall Farmer. Only gradually did it dawn on them just what they had gotten themselves into. Making Habitat come alive was going to be hard. Really hard. Farmer has called the Habitat project the most complicated single thing ever done with a Commodore 64. While he’s hardly unbiased, it’s also difficult to think of a more ambitious rival. To help you appreciate Habitat‘s scope, I’d like to give you a description of the experience it was meant to provide for the player.

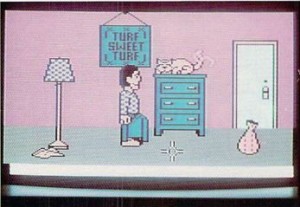

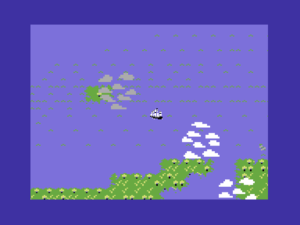

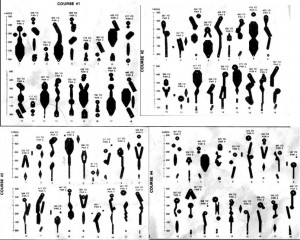

When you signed up for Habitat, your first task must be to create your new avatar, choosing your sex, your hair color, the shape of your head and your facial features. Your avatar was then given a room of his own to live in, complete with a dresser for storing things and a cat for cuddling. (Yes, dog lovers were out of luck — and no, it wasn’t possible to kill your cat.) You commanded your avatar by moving the cursor about the screen and tapping the joystick button, which yielded a radial menu of four items: “go” (walk to where the cursor points), “do” (manipulate some object or machine to which the cursor points), “get” (pick something up), and “put” (drop something, possibly inside a container). You could, for instance, select “do” over the dresser to open a drawer and reveal its contents, which you could then manipulate via “get” and “put.” Your avatar could normally only carry one thing at a time, but you could use a container, like the handy sack seen in the screenshot above, to carry many more.

The discrete areas, called regions in Habitat terminology, were linked with one another to form a grid or map, like the individual rooms of a text adventure. This, however, was one huge adventure game. There were many thousands of public regions, plus a “Turf Sweet Turf” for every player. By “going” to the door of your home turf, you could access the grand world outside your avatar’s humble abode. It was there that you’d begin to meet others.

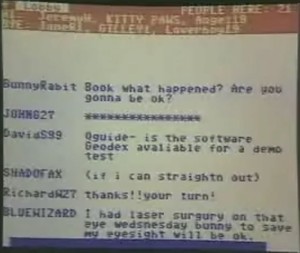

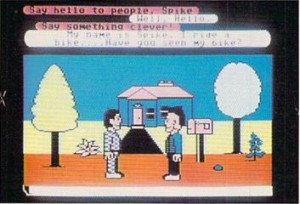

Due to technical constraints, only six avatars could occupy a region at the same time, but you could communicate with all of your region-mates simply by typing whatever you liked on the keyboard. The text you typed appeared as comic-style thought bubbles over your avatar’s head for all to read.

And that’s largely all you needed to know in order to interact with Habitat. Yet that’s enough to allow for a huge scope of social possibility, a fact of which Morningstar and Farmer were well aware and of which they were determined to take full advantage. Your room contained a telephone with a functioning telephone number other players could use to call you. Likewise, you could call them by looking them up in a virtual telephone book and dialing. If you preferred the dying art of letter-writing, every avatar had a mailbox before her domicile, with a functioning post system for delivering letters. There was a bank; every player got a stipend of 100 tokens every day she logged in, which she could spend as she would. There was a travel agency and resort destinations to which it could send you, stores to buy clothes and gadgets, bars and galleries and theaters. To facilitate large-scale events like plays, concerts, and poetry readings despite the six-avatars-per-region limit, Lucasfilm implemented something called “ghost mode,” which let you peer into a region without your avatar being actually embodied there — ideal for being a passive member of an audience. There was a “teleport” system for getting around the thousands of regions as quickly and easily as possible, and hotels for overnight trips to far-flung corners of the world. For those needing a definite external goal to work toward, an “Oracle” found in a park near the center of the world assigned adventure-game-like quests: “find the mystic orb of Xebop and return it to the Temple of Zak.” But even they were envisioned as social rather than solitary affairs, often requiring multiple avatars to pull off.

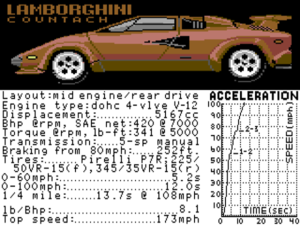

Perhaps the most amazing thing about Habitat is that it actually worked at all on a purely technical level, on client machines that Morningstar himself describes as little more than “toys,” with 1 MHz 8-bit processors, 64 K of memory, and an unstable connection running at as slow as 300 baud. The servers that housed this virtual world and managed all of the clients did have a few more resources at their disposal: QuantumLink, and thus Habitat, ran on a cluster of Motorola 68000-based computers built by a company called Stratus. Still, managing a virtual community proved to be far more expensive in both human and computer hours than anyone had anticipated. Lucasfilm’s contract with Quantum called for an environment capable of supporting 20,000 users, with the possibility of scaling it up easily to 50,000 if necessary. By the time the active user base reached 50 employees and insiders, Morningstar admits, Lucasfilm was already starting to feel “over our heads.”

We needed things for 20,000 people to do. They needed interesting places to visit — and since they can’t all be in the same place at the same time, they needed a lot of interesting places to visit — and things to do in those places. Each of those houses, towns, roads, shops, forests, theaters, arenas, and other places is a distinct entity that someone needs to design and create. Attempting to play the role of omniscient central planners, we were swamped.

Morningstar and Farmer nevertheless continued to plug away. In the first weeks of 1988 QuantumLink finally began a public beta test consisting of about 500 players who had been lucky enough to wind up with membership packets containing a special “early-access pass” for Habitat. It’s here that the Habitat story gets really fascinating, as Morningstar and Farmer bring the world’s first massively-multiplayer virtual community fully online. Many of the questions they were soon being forced to address, the situations they confronted, will sound familiar to anyone who’s ever played in Ultima Online, World of Warcraft, or Second Life, or for that matter just read about them. Here, then, are some dispatches from the front of an 8-bit Second Life that lived for just a few months in 1988.

Addiction!

From the bureau of things that never change: some users promptly became addicted, which was a real problem for them given that this was a paid beta test, billed at the usual QuantumLink “premium” rate of $3.60 per hour. Some were soon racking up monthly bills of $200 or more, corresponding to well over 50 hours of play. One managed to hit $1000 in one month, despite warnings sent to his email address at $300 and $600 that he might want to “check out his usage in the billing section.” Horrifying as this was on one level, Lucasfilm and QuantumLink couldn’t help but note that in theory they would only need twenty more users just like him to cover all of their operating expenses and make Habitat profitable.

The One-Percenters

Seeking to make Habitat a believable place, Lucasfilm included richer and poorer areas, discount shops and luxury boutiques with largely the same goods but very different prices. Trouble began when a few players realized that they could actually pawn items in a rich area for more money than it cost to buy them new in a poor. They spent an entire night trekking back and forth, buying low and selling high. By morning they had effectively wrecked Habitat‘s economy, inflating the money supply by a factor of five and making themselves almost inconceivably rich in contrast to everyone else. These nouveaux riches began to usurp power for themselves, getting others to do their bidding for trifling (to them) amounts of money, dispensing bread and circuses to the masses in the form of games and treasure hunts. With little outlet for their immense fortunes in spite of all their best efforts to spend them, the superrich ended up establishing a lucrative trade amongst themselves in what became Habitat‘s most ostentatious symbol of conspicuous consumption: custom heads for their avatars.

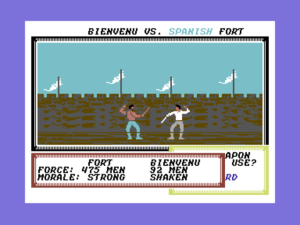

Robbery! Murder!

Weapons could be purchased in Habitat and player-versus-player conflict was allowed in the so-called “wilderness areas” outside of city limits, although the consequences of “death” were relatively mild: everything the dead avatar was carrying would be dumped onto the ground where she had been standing, and she would then be teleported back to her home turf, once again intact. Of course, it took about five minutes for someone to start randomly shooting people in order to take their stuff. This led to…

Law and Order Must Be Imposed!

The inhabitants decided that a police department must be established, and held elections for sheriff. Inevitably, the guy who won by a landslide was one of the one-percenters, who could afford a campaign on a scale of which the other candidates could only dream. Did someone say something about the role of money in politics?

Christianity Under Siege!

The first virtual church was opened by a Greek Orthodox minister. Those who wanted to join his flock were forbidden from stealing or engaging in any sort of violence. Unfortunately, whenever the minister and his flock weren’t around other players would march in, strip the church bare, and pawn the lot. The minister finally had to appeal directly to Lucasfilm for a special dispensation: a lock for his church.

Family Values

While there is no record of any relationships formed inside Habitat escaping into the real world, there were at least three virtual-world weddings, all taking place in that aforementioned church. Lucasfilm helpfully joined the newlyweds’ turfs together for cohabitation. The first virtual divorce followed the first virtual marriage by just two weeks.

Dangerous Bedfellows

It was possible for players to “sleep over” in other players’ turfs rather than their own, if invited inside. Soon con artists started finagling such invitations from naive players, then logging in while the victim still slept blissfully and absconding with everything in the room.

It’s About Ethics in In-Game Journalism!

A couple of enterprising players founded a newspaper, The Weekly Rant, consisting of as many as fifty pages full of news, fiction, classified advertisements, and announcements (including news of weddings and divorces). Absolutely everyone in Habitat was soon using it as an essential resource until, after a dispute about editorial content — the publisher wanted a shorter newspaper with less fiction — the editor abruptly quit. Habitat felt the loss keenly for all of its remaining days.

Arms Negotiations

For a special area they were creating called “The Dungeon of Death,” two players convinced Lucasfilm to build them special “elephant guns” that could kill another avatar in one shot instead of the usual twelve or so, on the condition that they would use them only in the person of their alter egos “Death” and “The Shadow” who lurked within the dungeon. Embarrassingly, one day while playing Death on loan Randall Farmer himself managed to get himself killed by another player, who promptly scooped up the gun. An ordinary player, unbound by any strictures whatsoever, now had this massively destabilizing weapon in her hot little hands. After threats and negotiations, a deal was struck: 10,000 tokens to buy the gun back. Echoing a thousand Hollywood thrillers, the two parties met on the grounds of Habitat‘s largest public park to make a tense exchange through a neutral intermediary; one can’t help but imagine their respective posses lurking tensely in the bushes all around in case trouble started.

The immediate transplantation of real-world societal structures and, one might say, societal woes into Habitat might be read as depressing. On another level, though, it was a sign that Habitat worked, that it had become a real community. “In a real system that is going to be used by real people,” wrote Morningstar and Farmer later, “it is a mistake to assume that the users will all undertake the sorts of noble and sublime activities which you created the system to enable. Most of them will not. Cyberspace may indeed change humanity, but only if it begins with humanity as it really is.”

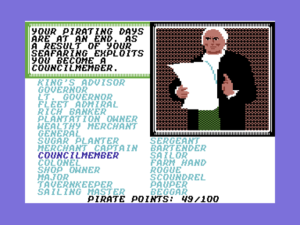

In time, Morningstar and Farmer came to categorize the inhabitants of Habitat into five categories that perhaps apply almost equally well to the real world.

The Passive: Easily 50 percent of the number of users fall into this category, but they probably use only 20 percent of the connect time (rough estimates). They tend to show up for events ad-hoc and when the mood strikes. This group must be led by the hand to participate. They tend to want to “be entertained” with no effort, like watching TV.

The Active: This group is the next largest, and made up the bulk of the paying user-hours. The Active user participates in two to five hours of activities a week. They ALWAYS have a copy of the latest paper (and gripe if it comes out late).

The Motivators: The real heroes of Habitat. The Motivators understand that Habitat is what they make of it. They set out to change it. They throw parties, start institutions, open businesses, run for office, start moral debates, become outlaws, win contests.

The Caretakers: The Caretakers are “mature” Motivators. They tend to help the new users, control personal conflicts, record bugs, suggest improvements, run their own contests, officiate at functions, and in general keep things running smoothly.

The Geek Gods: The operator’s job is most important. It really is like being a Greek God from the ancient writings. The Oracle grants wishes and introduces new items/rules into the world. With one bold stroke of the keyboard, the operator can create/eliminate bank accounts, entire city blocks, or the family business. This is a difficult task as one must consider the repercussions of any “external” events to the world. Think about this: would you be mad at “God” if one day suddenly electricity didn’t work anymore? Habitat IS a world. As such, someone should run it that has experience in that area. A Geek God must understand both consistency in fictional worlds and the people who inhabit it.

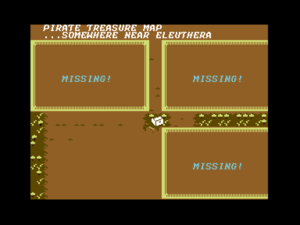

In the beginning, Morningstar and Farmer tried to micromanage the world, but it quickly became clear that this would be impossible, even with just 500 players. Designing a massively-multiplayer game is a fundamentally different discipline than designing for a single player. A player in a single-player game expects and deserves to have the world revolve around her; a player in a massively-multiplayer game is but one among many would-be heroes. The reality of this difference, a difference which Morningstar and Farmer were amongst the first people in the world to confront, became clear with their first attempt at a large-scale community treasure hunt, the so-called “D’nalsi Island Adventure.” Farmer spent weeks designing and building the quest and the 100-region island that would house its goal, the lost “Amulet of Salesh,” hidden away in a remote, seldom-visited corner of the world. After announcing the quest at a special community meeting held in the county courthouse, Farmer and Morningstar sat back to watch the players go to work, anticipating it would take them some days to return with the amulet. As it turned out, someone found the island within fifteen minutes, then recovered the amulet therein within eight hours. Most players were never even aware that the quest was happening before it was all over.

Clearly, Habitat could not depend on such externally imposed quests, quests which the most knowledgeable and the most powerful were always destined to win. What happened inside Habitat would instead have to be driven by the players themselves. By the time the beta ended, Morningstar and Farmer had shifted their thinking entirely, realizing that the success of this virtual world would depend on them being able to move enough users along each step of the continuum outlined above, from curious but Passive non-participants to Geek Gods who had the competency and the interest to start to play a major role in the underlying workings of the world itself. (One might also say that this is the main goal a real-world society has for each succeeding generation.) From the standpoint of game design, this would prove to be the number-one lesson of Habitat — a sort of transcendence of game design. Morningstar and Farmer made a conscious effort to begin to think more like facilitators than game designers. When players came to them asking for an elephant gun or a church, they asked them what they planned to use it for and, if all seemed kosher, did their best to provide.

And then, just like that, it was suddenly all over. The beta ended and Habitat went dark forever, leaving a million might-have-beens in its wake. Steve Arnold:

We found that we had pushed the C-64 to its limits, and, if we had to do it all over again — and I’m not trying to insult C-64 owners — we really would have developed the Habitat program on a different system. Once we finished Habitat and really sat down and looked at it, we realized there was a lot more technology needed to do multiplayer gaming — a lot more than we could do effectively on the C-64.

Habitat just didn’t scale well, wasn’t going to work with 20,000 or 50,000 players. In addition to the problems on the client side, Quantum noted that Habitat, even with just 500 players, had already consumed an inordinate amount of processing power on their servers during the beta period. They claimed that trying to deliver a full-scale Habitat would require a massive investment in infrastructure that they just weren’t in a position to pay for.

That said, there were doubtless other factors at play in the mutual reluctance of both Quantum and Lucasfilm to commit yet more resources to making Habitat live for real. They were now well into 1988, and it was becoming clear that the Commodore 64, a computing evergreen for so long, was beginning to fade at last. This reality left neither partner eager to commit more resources to expensive long-range projects for the platform. Lucasfilm was shifting to MS-DOS as their front-line development platform, while Quantum was now pouring most of the revenue they were earning from QuantumLink into new online services targeting other platforms rather than continuing to make major improvements to the old service.

Lucasfilm washed their hands of Habitat in mid-1988 by selling the whole technology package to Fujitsu, who used it to create Club Caribe, a stripped-down environment of a relatively compact 500 regions, on QuantumLink in 1989. It essentially functioned as an amusing chat interface, with most of the elements that made Habitat a real, functioning community stripped away. “Don’t get the idea that Club Caribe is a half-baked attempt to implement a vision that was too far ahead of its time,” wrote one magazine reviewer eager not to lose QuantumLink’s advertising dollars but also not quite willing to completely avoid the truth. That, of course, was exactly what it was, although even as Club Caribe the technology was still more than able to impress those who weren’t aware of the full scope of Chip Morningstar’s original dream. Habitat‘s technology continued to live on to one degree or another in other Fujitsu projects spanning much of the next decade, such as the Habitat Japan that was launched in 1990 and another virtual world called WorldsAway that was launched on CompuServe during that service’s twilight years of the mid-1990s. Yet it wouldn’t be until Ultima Online in 1997 that an online virtual world of quite the same scope and complexity as the original Habitat would be attempted again, and not until Second Life in 2003 that a functioning virtual community of quite the same player-driven character would be dared again. (Second Life also has a more direct connection to Habitat: F. Randall Farmer was a consultant on the later venture.) Such spans are practically millennia in the fast-paced world of computers. Habitat was perhaps doomed to fail from the beginning, but if you’re going to fail you might as well make it a failure for the ages.

QuantumLink, and the Club Caribe to be found within it, persisted as what might be most charitably described as a “legacy service” for a surprisingly long time, not finally going dark until November 1, 1994, just a few days shy of its ninth birthday and after the death of Commodore itself. By that time, however, it was little more than an afterthought for its parent company, now one of the biggest success stories of the nascent Internet boom. After some hiccups in the form of failed AppleLink and PCLink services, you see, Steve Case had finally hit paydirt with America Online, which became the new name of Quantum Computer Services itself in 1991. I’m going to guess that you might have heard of them. If not… well, stick around. We’ll get there.

(Sources: the book Droidmaker by Michael Rubin; Compute!’s Gazette of January 1985, May 1985, March 1986, January 1987, December 1987, and January 1989; Run of August 1986 and November 1989; Commodore Microcomputers of November/December 1986; Computer and Video Games of May 1987. Two episodes of the television show Computer Chronicles, “Modems and Bulletin Boards” from 1985 and “Online Services Part One” from 1987, are pertinent. The Internet Archive gives access to a now-defunct site created by Keith Elkin that was devoted to Habitat. The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment’s site hosts a Lucasfilm-to-Fujitsu technology-transfer document dating from the summer of 1988 that’s full of fascinating information and insights. Finally, Chip Morningstar and F. Randall Farmer have a website full of still more invaluable information and insights.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Richard Garriott applied the same term to a game even earlier than Morningstar, during the development of Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, but his usage applies specifically to the ethical quest that forms the plot of that game: the player’s goal is to become an “avatar of virtue.” The more generalized use of the term in videogames is better attributed to Morningstar, even if Garriott’s usage probably better reflects its real implications in Hinduism. |

|---|