You can’t say civilization don’t advance. In every war, they kill you in a new way.

— Will Rogers

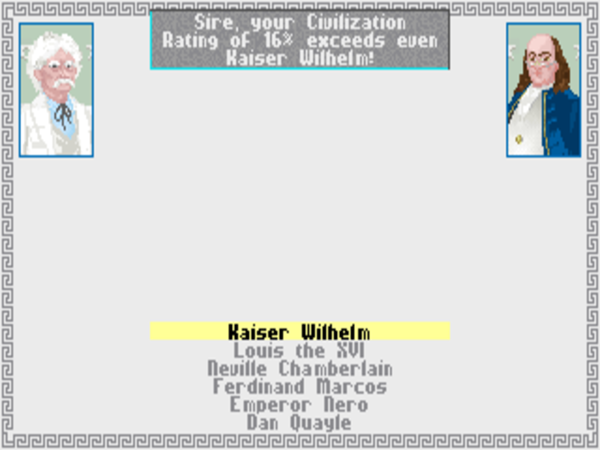

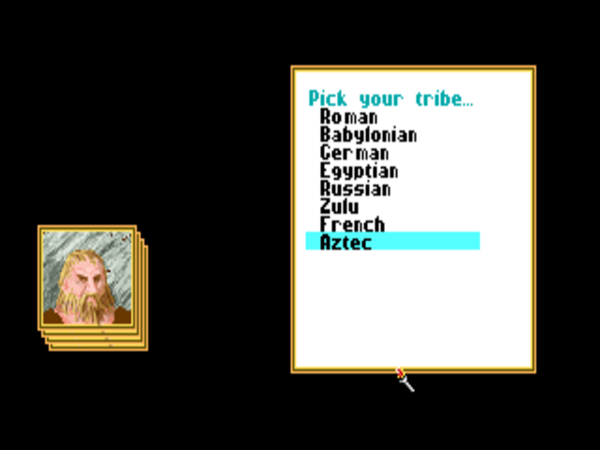

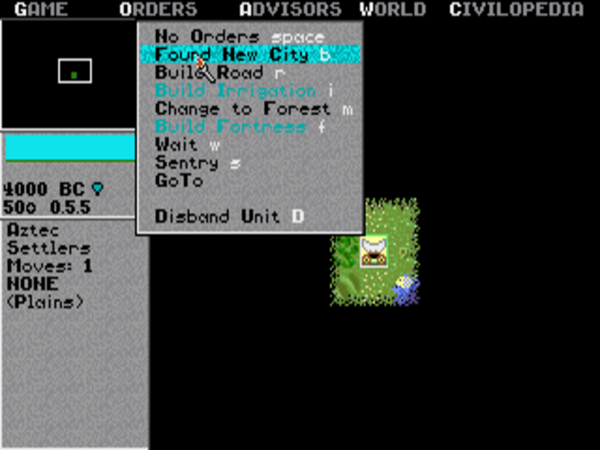

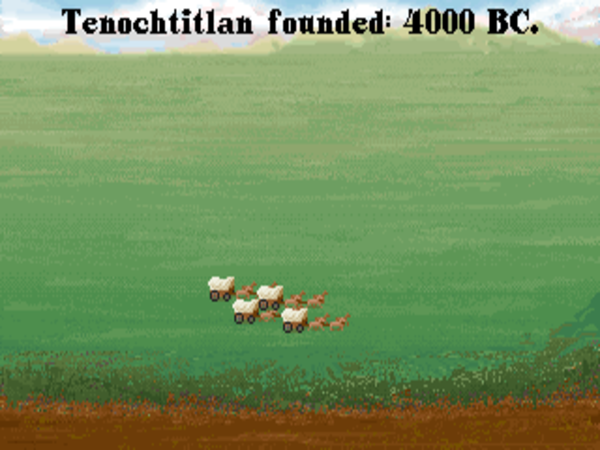

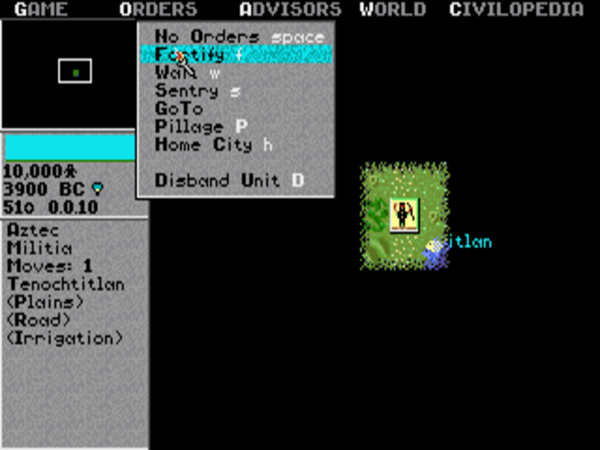

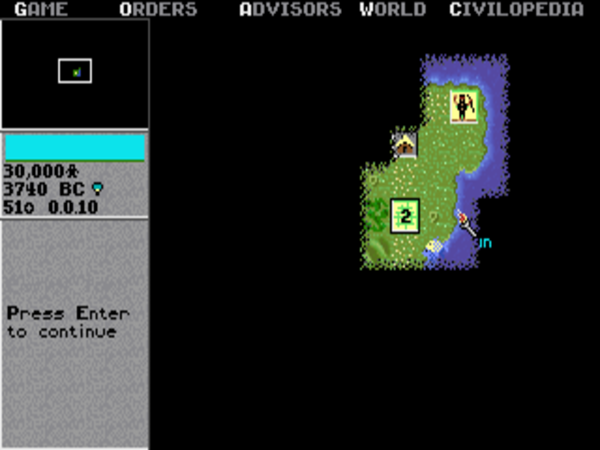

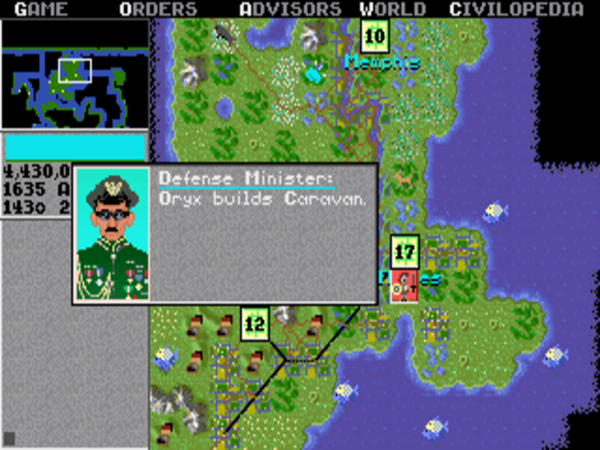

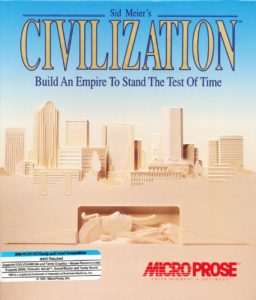

Civilization is a game for all time, but the original version of Civilization, as created by Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley and published by MicroProse in 1991, is also a game thoroughly of its time. When you finish guiding your civilization’s history, whether because you’ve conquered the world, been conquered by the world, flown to Alpha Centauri, or simply retired, you’re ranked on a scale of real history’s leaders. If you’ve played really, really badly — as in, closing-your-eyes-and-clicking-randomly badly — you find yourself equated to Dan Quayle, the United States’s vice president as of 1991.

Quayle has long since slunk out of public life, meaning that younger players who try out the game today will likely fail to get the joke here. In his day, however, his vacuousness was legendary enough to make even the most hardened would-be assassin think twice before visiting ill upon President George H.W. Bush. Among Quayle’s greatest hits were the time he claimed the Holocaust had happened in the United States, the time he claimed Mars had a breathable atmosphere and canals filled with water, and the time he lost a spelling bee to a twelve-year-old by misspelling “potato.” And then there was the feud he started with the sitcom character Murphy Brown when she chose to have a child out of wedlock, raising the question of whether he knew that the little people he saw inside his television didn’t actually live there. It says much about what a universal figure of derision he had become by 1991 that Meier and Shelley, in no hurry to offend any potential customer of any political persuasion, nevertheless felt free to mock him in this way as the ne plus ultra of air-headed politicians. Everybody felt free to mock Dan Quayle.

But the spirit of the times in which Civilization was made is woven much deeper into its fabric than a joke tossed onto an end-of-game leader board. In fact, it’s inseparable from the game’s single most important identifying feature. The Advances Chart of which I’ve already made so much reflects a view of history as a well-nigh inevitable narrative of progress — a view that had rather fallen out of favor for much of the twentieth century, but which had come roaring back now at the end of it, prompted by the ending of the Cold War.

It’s very difficult to adequately convey today just how that ending felt to those of us in the West who had lived through what preceded it. Just a few years before, we had shivered in our beds after watching The Day After in the United States or Threads in Britain, while Ronald Reagan droned on obliviously about the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” A decade earlier, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had said that the Cold War would be “unending”: “We must learn to conduct foreign policy without escape and without respite. This condition will not go away.” Which was perhaps just as well, given that no one could seem to formulate an endgame for it that didn’t leave the world a heap of irradiated ashes. It was very nearly the conventional wisdom that someday, somehow, a mistake would be made by one side or the other, or one side would simply find itself backed too far into a corner. At that point, the missiles would fly, and that would be that. The logic of history seemed to be on the side of such pessimism. After all, what other weapon in the long history of warfare had humanity ever invented and then not used?

And then, with head-snapping speed, it was all simply… over. Over, for the most part, peacefully. In a series of events so improbable no novelist would ever have dared write them down, one side just decided to give up. The Berlin Wall came down, the Iron Curtain opened, and the Cold War ended in the most blessed anticlimax in the history of the world. As Meier and Shelley were finishing Civilization, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was entering its final stages. In June of 1991, Boris Yeltsin became the first democratically elected president of the nascent “Russian Federation.” In August, the world held its breath as a cabal of communist hardliners mounted a last-ditch coup in the hope of restoring the old order, only to exhale again when the coup collapsed three days later. And on December 26, 1991, a couple of weeks after Civilization had reached store shelves, the Soviet Union was officially dissolved. Russia was once again just Russia.

For those of us in the West, the whole course of events was rather hard to fathom; it was hard to know how to react to suddenly not living under the dark threat of nuclear annihilation. But Americans at least, a people who seldom need much encouragement to wave their flags and play their anthem, soon got with the program and started celebrating the historical triumph of their “way of life.” If they needed any further encouragement, the country’s first post-Cold War military adventure, the pushing of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq out of Kuwait, was being televised live every night on CNN even as the Soviet Union was still winding down. That war proved the perfect antidote to the lingering malaise of Vietnam; it was, at least from the perspective of 30,000 feet shown on CNN, swift and clean, all of the things the “police actions” of the Cold War had so seldom been. The United States was unchallenged in the world, in the ascendant as never before.

The feeling of exaltation wasn’t confined to flag-waving populists. The most-discussed book of 1992 among the chattering classes had no less grandiose a title than The End of History and the Last Man. It was the perfect book for the times, an explication of all the reasons that the United States had triumphed in the Cold War and could now look forward to a world molded in its image. Written by a heretofore obscure member of the RAND think tank named Francis Fukuyama, and based on a journal article he had first published in 1989, the book identified “a fundamental process at work that dictates a common evolutionary pattern for all human societies — in short, something like a Universal History of mankind in the direction of liberal democracy.” (“Liberal” in this context refers to classical liberalism — i.e., prioritizing the sanctity of the individual over the goals of the collective — rather than the word’s modern political connotations.) The central question of history, Fukuyama argued, had been that of how humanity should best order itself, economically and politically, in order to ensure the best possible material, social, and spiritual state of being for everyone. With the end of the Cold War, communism and totalitarianism, the last great challengers to capitalism and democracy by way of an answer to that question, had given up the ghost. From now on, liberal democracy would reign supreme, meaning that, while events would certainly continue, history had come to the fruition toward which it had been building through all the centuries past.

More discussed than actually read even in its heyday, Fukuyama’s book has since become an all-purpose punching bag, described as hopelessly naive in right-wing realpolitik circles and morally reprehensible in left-wing postmodernist and Marxist circles. Widely denounced by the latter group in particular as a purveyor of “jingoist triumphalism” in service of American hegemony, Fukuyama felt compelled to stress in a new 2003 afterword to The End of History that he actually saw the European Union as a better model for liberal democracy’s future than the government of his own country. His book is in many ways a book of its time — an example of a history book itself becoming history — but it’s neither as jingoistic nor as naive as its current reputation would suggest. Most of Fukuyama’s critics fail to address the fact that the idea of a secular historical eschatology hardly originated with him. In fact, he takes pains in the book to situate it within a long-established historiographical tradition, albeit updated to account for such an earth-shaking event as the end of the Cold War.

History as evolutionary progress is an Enlightenment ideal that ironically predates Charles Darwin’s theory of biological evolution. Without it, the American and French Revolutions, those two great attempts to bring concrete form to Enlightenment ideas about human rights and just government, would have been unimaginable. During the decades prior to those revolutions, thinkers like Immanuel Kant, Baruch Spinoza, Thomas Hobbes, David Hume, and Adam Smith had articulated a new way of looking at the world, based on reason, science, humanism, and, yes, progress. “With our understanding of the world advanced by science and our circle of sympathy expanded through reason and cosmopolitanism,” writes the modern-day cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker of the Enlightenment, “humanity could make intellectual and moral progress. It need not resign itself to the miseries and irrationalities of the present, nor try to turn back the clock to a lost golden age.” To be a progressive, then or now, is to believe in the actuality or at least the potentiality of human history as a narrative of progress. It implies a realistic, fact-based approach to problem-solving that prefers to look forward to the future rather than back to the past.

But of course, any rousing narrative of progress worth its salt needs to have a proper bang-up climax. It was the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in the early 1800s who first proposed the notion of a point of fruition toward which the history of humanity was leading. Indeed, he went so far as to claim that history may have reached this goal already in his own time, with the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and Napoleon’s victory over Prussia at the Battle of Jena in 1806 having proved the superiority of his time’s version of the modern liberal state. (Francis Fukuyama had nothing on this guy when it came to premature declarations of mission accomplished.) Hegel connected his notions of historical progress with a Greek word from classical theology: thymos. It’s difficult to concisely translate, but it connotes the social worth of an individual, the sum total of her competencies and predilections. The ideal society, according to Hegel, is one where each person has the opportunity to become this best self — or, we might say today, to use another word that smacks dreadfully of pop psychology, to “self-actualize.”

This, then, was the natural end point toward which all of history to date had been struggling. As befits a philosopher of the idealist school, Hegel gave the narrative of progress an idealistic tinge which still clings to its alleged rationality even today, whether it takes as its climax Hegel’s universal thymos, Fukuyama’s stable democratic world order, or for that matter Civilization‘s trip to Alpha Centauri.

Narratives of progress had a natural appeal during the nineteenth century, a relatively peaceful era once Napoleon had been dispensed with, and one in which real, tangible signs of progress were appearing at an unprecedented pace, in the form of new ideas and new inventions. In this time before nuclear Armageddon or global warming had crossed anyone’s most remote imaginings, the wonders of technological progress in particular — the railroad, the telegraph, the light bulb — were regarded as an unalloyed positive force in the world. By the latter half of the century, almost everyone seemed to be a techno-progressive. “Upon the whole,” wrote the British statesman William Ewart Gladstone in 1887, “we who lived fifty, sixty, seventy years back have lived into a gentler time.”

Even the less sanguine thinkers couldn’t resist the allure of the narrative of progress. On the contrary: it was Karl Marx among all nineteenth-century thinkers who devoted the most energy to a cherished historical eschatology. With Enlightened scientific precision, he laid out six “phases of history” through which the world must inevitably pass: primitive communism, the slave society, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and finally true communism. He disagreed with Hegel that liberalism — i.e., capitalism — could mark the end of history by noting, by no means without justification, that the thymos-fulfilling nations the latter praised actually empowered only a tiny portion of their populations, that being white men of the moneyed classes; these were the only people Hegel tended to think of when he talked about “the people.”

But even in the nineteenth century the narrative of progress had its critics. The most vocal among them was yet another German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche. Whereas Hegel spoke of the thymos, Nietzsche preferred megalothymia: the need of the superior man to assert his superiority. To Nietzsche, nobility was found only in conflict. All of these so-called “progressive” institutions — such as democracy and human rights — were creating a world of “hollow-chested” men, alienated from the real essence of life; the modern nation-state was “the coldest of all cold monsters.” Hegel had imagined a world where slaves would be freed from their shackles. Maybe so, said Nietzsche — but they will still be slaves. Instead of history as a ladder, Nietzsche preferred to see it as a loop — an “eternal recurrence.” Whether progress was defined in terms of railroads, telegraphs, and light bulbs or social contracts, human rights, and democracies, it was all nonsense, merely the window dressing for the eternal human cycle of strife and striving.

While Nietzsche’s views were decidedly idiosyncratic in his own century, the narrative of progress’s critics grew enormously in number in the century which followed. In contrast to the peace and prosperity that marked the last few decades of the nineteenth century in particular, the first half of the twentieth century was dominated by a devastating one-two punch: the two bloodiest wars in the whole bloody history of human warfare, the second of them accompanied by one of the most concerted attempts at genocide in man’s whole history of inhumanity to man. It wasn’t lost on anyone that the country which had conceived this last, and then proceeded to carry it out with such remorseless Teutonic efficiency, was the very place where Hegel had lived and written about his ideals of ethical progress. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, Josef Stalin was turning Marx’s dreams of a communist utopia into another brutal farce. In the face of all this, the narrative of progress seemed at best a quaint notion, at worst a cruel joke. After all, it was only the supposedly civilizing fruits of progress — technology, bureaucracy, a rules-based system of order — that allowed Hitler and Stalin’s reigns of terror to be so tragically effective.

Even when World War II ended with the good guys victorious, any sense that the narrative of progress could now be considered firmly back on track was undone by the specter of the atomic bomb. Maybe, thought many, the end goal toward which the narrative was leading wasn’t an Enlightened world but rather nuclear apocalypse. In his 1960 novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter M. Miller, Jr., introduced a grotesque new spin on Nietzsche’s old idea of the eternal recurrence. He proposed that human civilization might progress from the hunter-gatherer phase to the point of developing nuclear weapons, and then proceed to destroy itself — again and again and again for all eternity. In 1980, the astronomer Carl Sagan upped the ante even further in his television miniseries Cosmos. Maybe, he proposed, the reason we had failed to find any evidence of intelligent extraterrestrial life was because any species which reached roughly humanity’s current level of technological development was doomed to annihilate itself within a handful of years — the eternal recurrence on a cosmic scale.

But then came that wonderful day in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down. What followed was the most ebullient few years of the twentieth century. The peace treaty which had concluded World War I had felt like something of a hollow sham even at the time, while the ending of World War II had been sobered by the creeping shadows of the atomic bomb and the Cold War. But now, at the end of the twentieth century’s third great global conflict of ideologies, there was seemingly no reason not to feel thoroughly positive about the world’s future. The only problems remaining in the world were small in comparison to the prospect of nuclear annihilation, and they could be dealt with by a united world community of democratic nations, as was demonstrated by the clean, quick, and painless First Gulf War. From the perspective of the early 1990s, even much of the century’s darkest history could be seen in a decidedly different light. Amidst all of the wars and genocides, the century had produced agents for peace like the United Nations, along with extraordinary scientific, medical, and technological progress that had made the lives of countless people better on countless fronts. And, to cap it all off, the fact remained that we hadn’t annihilated each other. Maybe the narrative of progress was as vital as ever. Maybe it just worked in more roundabout and mysterious ways than anticipated. Maybe it was sometimes just hard to see the forest of overall progress amidst all the trees of current events.

As we all know, progress’s moment of triumph would prove even more short-lived than most of history’s golden ages. Within a few years of the fall of the Berlin Wall, an unspeakably brutal war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was showing that age-old ethnic and religious animus could still be more powerful than idealistic talk about democracy and human rights. Well before the end of the 1990s, it was becoming clear that Russia, rather than striding forward to join the international community of liberal democracies, was sliding backward into economic chaos and political corruption, priming the pump for a return to authoritarian rule. And then came September 11, 2001, the definitive ending of the era that would come to be regarded not as the beginning of humanity’s permanently peaceful and prosperous post-history but as the briefly tranquil intermission between the Cold War and a seemingly eternal War on Terror. In a future article, we’ll try to reckon with the changes that have come to the world since those ebullient days of the early 1990s.

Right now, however, let’s turn back to Civilization. Even as I continue to emphasize that Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley weren’t out to make a political statement with their game of everything, I must also note that its embrace of the narrative of progress as its core mechanic, combined with its spirit of rational practicality and a certain idealism, wind up making it a very progressive work indeed. Loathe though he has always been to talk about politics, Meier has admitted to a measure of pride at having included global warming in the game; if you don’t control your modern civilization’s pollution levels, your coastal cities will literally get swallowed up by the encroaching ocean.

I want to stress that “progressive” as I use it here is not a synonym for (non-classically) “liberal”; it’s perfectly possible to be a progressive who believes in smaller government, possible even to be a progressive libertarian. Still, even at the time of the game’s release, when the American right tended to be more trusting of science and objective truth than they’ve become today, its pragmatism about our fragile planet didn’t always sit well with MicroProse’s traditional customer base of largely conservative military-simulation and wargame fans. Computer Gaming World‘s Alan Emrich, who was more than largely conservative, penned the hilarious passage below in his otherwise extremely positive review of the game. It can probably stand in for many a crusty old grognard’s reaction to some of the game’s most interesting aspects (“politically correct,” it seems, was 1991’s version of “social-justice warrior”):

Civilization strives to be a “hip” game, and deals with popular social issues from the standpoint of “political correctness.” Thus, global warming is a tremendous threat. Odd, for such a recent, unproven theory. Evolution is expressed in the game’s introduction, but at least that debate has been around a while. Pollution, therefore, becomes a society’s primary focus after industrialization takes place, with players being channeled toward more politically-correct power plants, recycling centers, and mass transit to address the problem. Even the beta-test “super-highway” Wonder of the World gave way to “women’s suffrage.” While women’s suffrage is a novel concept for its effect during gameplay, it is also another brick in the wall of political correctness.

One hardly knows where to start with this. Should we begin with the bizarre idea that any designer of a massive computer strategy game, about the most unhip thing in the world, would ever have striven to be “hip?” Or with the idea that evolution might still be up for “debate?” Or with the idea that recycling centers and mass transit, and letting women vote, for God’s sake, are dubious notions born of political correctness, that apparent source of all the world’s evils? Or with the last mangled metaphor, which seems to be saying the opposite of what it wants to say? (Was Emrich listening to too much Pink Floyd at the time?) Instead of snarking further, I’m just going to move on.

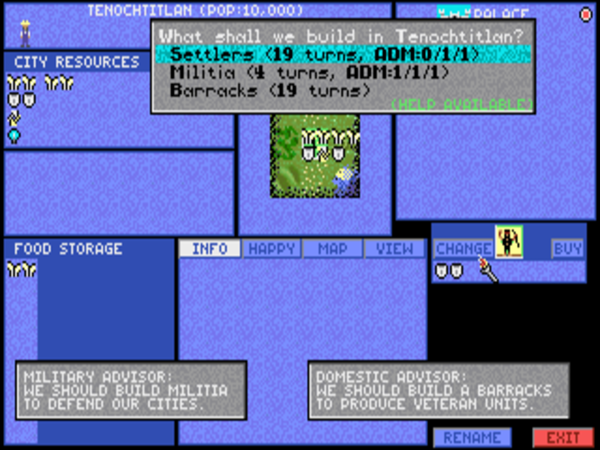

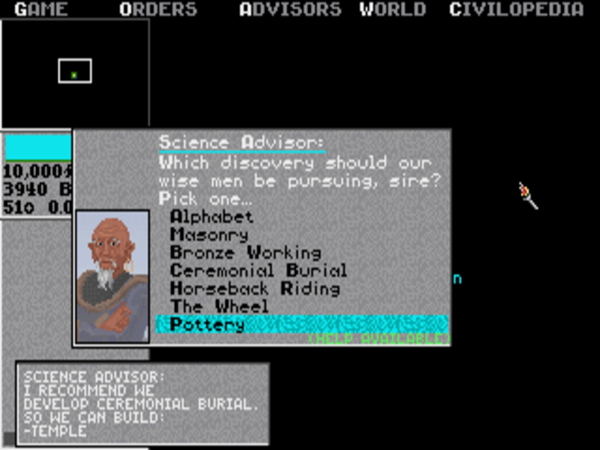

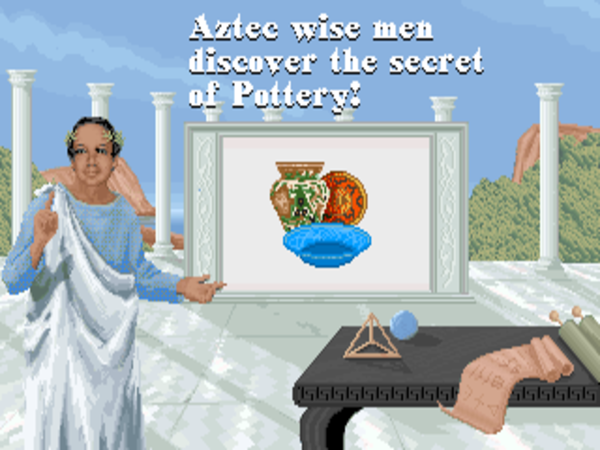

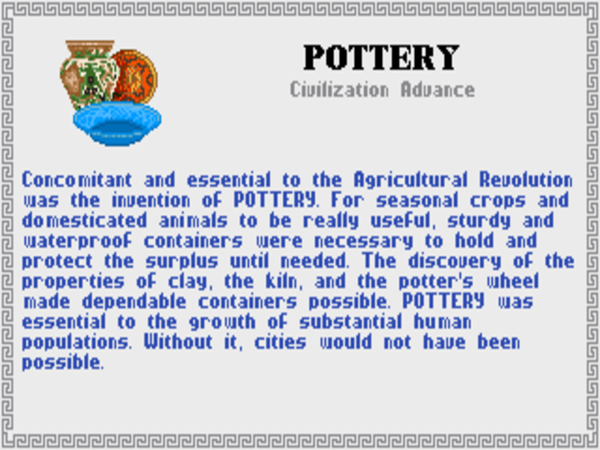

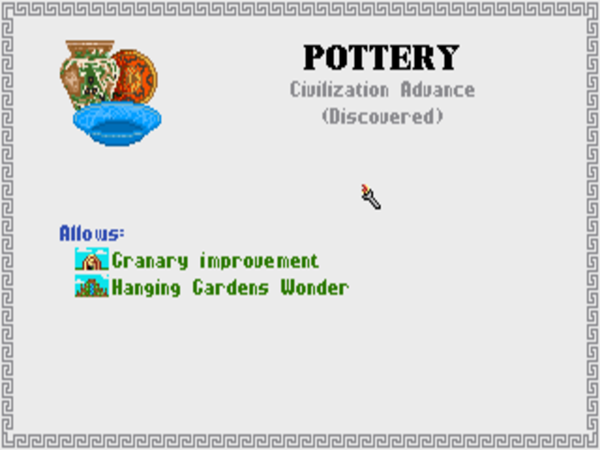

A more useful subject to examine right now might be just what kind of progress it is that Civilization‘s Advances Chart represents. The belief to which the game seems to subscribe, that progress in technology and hard science will inevitably drive the broader culture forward, is sometimes referred to as technological determinism. It can be contrasted with the more metaphysical narrative of progress favored by the likes of Hegel, as it can with the social-collective narrative of progress favored by Marx. Unsurprisingly, it tends to find its most enthusiastic fans among scientists, engineers, and science-fiction writers.

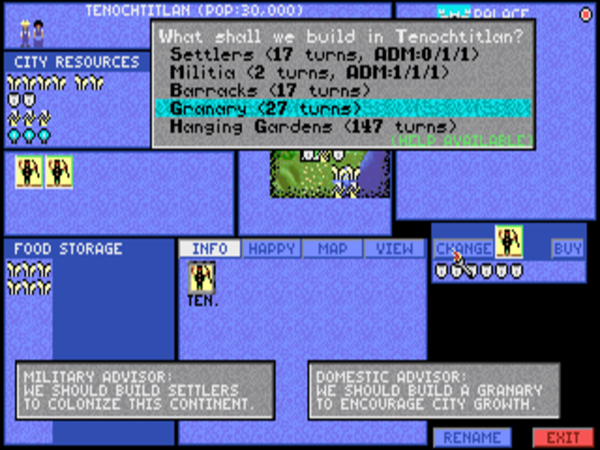

Given the sort of work it is, it makes a lot of practical sense for Civilization to cast its lot with the technologists’ camp; it is, after all, much easier to build into a strategy game the results of the development of the musket than it is to chart the impact of a William Shakespeare. Even outside the rules of a strategy game, for that matter, it’s far more difficult to map great art onto a narrative of progress than it is other great human achievements. While scientists, engineers, and even philosophers build upon one another’s work in fairly obvious way, great artists often stand alone; Shakespeare continues to be widely acknowledged today as the greatest writer of English ever to have lived, even as progress has long since swept all other aspects of his century aside.

Still, importantly, Shakespeare is in the game, as are Michelangelo and Bach, and as are markers of social progress like women’s suffrage and labor unions. (By way of confirming all of Alan Emrich’s deepest suspicions, the game makes communism a prerequisite for the last.) It is, in other words, not remarkable that Civilization on the whole favors a “hard” form of progress; what is remarkable is the degree to which it manages to depart from such a bias from time to time. If the game sometimes strains to find a concrete advantage to confer upon the softer forms of progress — women’s suffrage makes your population less prone to unhappiness, which makes at least a modicum of sense; labor unions give you access to “mechanized infantry” units, which makes pretty much no sense whatsoever — its heart is nevertheless in the right place.

The first people ever to pen a study of Civilization‘s assumptions about history were none other than our old friend Alan Emrich and his fellow Computer Gaming World scribe Johnny L. Wilson, who did so together in the context of a strategy guide called Civilization: or Rome on 640K a Day. It has to be one of the most interesting books ever written about a computer game; it’s actually fairly useless as a practical strategy guide, but is full of fascinating observations about the deeper implications of Civilization as a simulation of history. Wilson writes from a forthrightly liberal point of view, while Emrich is, as we’ve already seen, deeply conservative, and the frisson between the two gives the book additional zest. Here’s what it has to say about Civilization‘s implementation of the narrative of progress:

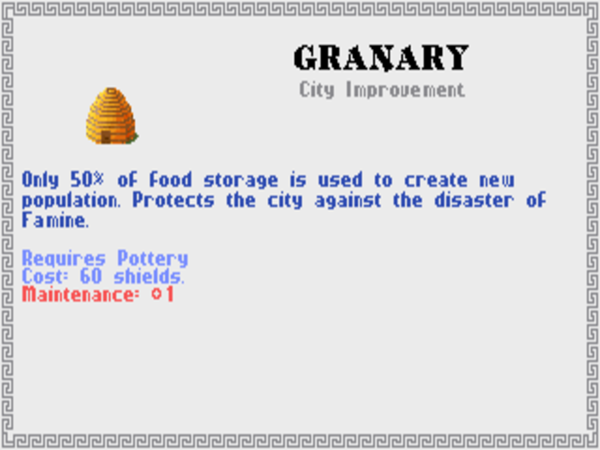

To be civilized in terms of Sid Meier’s Civilization means to be making material progress in terms of economic well-being and scientific advancement. The game has an underlying belief in such progress. In fact, this dogma is so strong that there is actually no problem in Sid Meier’s Civilization that cannot be solved by human effort (using settler units) or more technology. There are, as a correspondent named Gary Boone wrote to us shortly after the game’s release, no Luddites (reactionary anti-technological activists during the Industrial Revolution) in this game’s universe. It is, to paraphrase Voltaire’s Dr. Pangloss, the best of all progressing worlds.

Many an earnest progressive in the real world has doubtless wished for such an alternate universe. Galileo wished he could write about heliocentrism without being hauled before an ecclesiastical court; Einstein wished he could pursue his Theory of Relativity without contending with a pitchfork-wielding mob of Isaac Newton disciples; modern researchers wish they could explore gene therapy without people forever trying to take their stem cells away. All of these wishes come true in Civilization, that best of all progressing worlds.

Of course, even those of us who proudly call ourselves progressives need to recognize that the narrative of progress has its caveats. Many of the narrative’s adherents, not least among them Civilization, have tended to see it as an historical inevitability. Notably, Civilization has no mechanisms by which advances, once acquired, can be lost again. Yet clearly this has happened in real human history, most famously during the thousand-year interregnum between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance, during the early centuries of which humanity in the West was actively regressing by countless measures; much knowledge, along with much art and literature, was lost forever during the so-called Dark Ages. (Far more would have been lost had not the Muslim world saved much of Europe’s heritage from the neglect and depredations of the European peoples — much as is done, come to think of it, by a small society of monks after each successive Apocalypse in Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz.)

We should thus remember as we construct our narratives of progress for our own world that the data in favor of progress as an inevitability is thin on the ground indeed. We have only one history we can look back upon, making it very questionable to gather too many hard-and-fast rules therefrom. All but the most committed Luddite would agree that progress has occurred over the last several centuries, and at an ever-increasing rate at that, but we have no form of cosmic assurance that it will continue. “The simple faith in progress is not a conviction belonging to strength, but one belonging to acquiescence and hence to weakness,” wrote Norbert Wiener in 1950, going on to note that the sheer pace of progress in recent times had given those times a character unique in human history:

There is no use in looking anywhere in earlier history for parallels to the successful inventions of the steam engine, the steamboat, the locomotive, the modern smelting of metals, the telegraph, the transoceanic cable, the introduction of electric power, dynamite and the high-explosive missile, the airplane, the electric valve, and the atomic bomb. The inventions in metallurgy which heralded the origin of the Bronze Age are neither so concentrated in time nor so manifold as to offer a good counterexample. It is very well for the classical economist to assure us suavely that these changes are purely changes in degree, and that changes in degree do not vitiate historic parallels. The difference between a medicinal dose of strychnine and a fatal one is also only one of degree.

Civilization rather cleverly disguises this “difference of degree” by making each turn represent less and less time as you move through history. Nevertheless, progress at anything but the most glacial pace remains a fairly recent development that may be more of an historical anomaly than an inevitability.

Whatever else it is, the narrative of progress is also a deeply American view of history. The United States is young enough to have been born after progress in the abstract had become an idea in philosophy. Indeed, its origin story is inextricably bound up in Enlightenment idealism. That fact, combined with the fact that the United States has been fortunate enough to suffer very few major tragedies in its existence, has caused a version of the narrative of progress to become the default way of teaching American history at the pre-university level. One could thus say that every American citizen, this one included, is indoctrinated in the narrative of progress before reaching adulthood. This indoctrination can make it difficult to even notice the existence of other views of history.

Civilization, for its part, is a deeply American game, and much about the narrative of progress must have seemed self-evident to its designers, to the point that they never even thought about it. The game has garnered plenty of criticism in academia for its Americanisms. Matthew Kapell, for instance, in indelible academic fashion labels Civilization a “simulacrum” of the “American monomythic structure.” Such essays often have more of an ideological axe to grind than does the game itself, and strike me as rather unfair to a couple of designers who at the end of the day were just making a good-faith attempt to portray history as it looked to them. Still, we Americans would do well to keep in mind that our country’s view of history isn’t a universal one.

But if we shouldn’t trust in progress as inevitable, how should we think about it? To begin with, we might acknowledge that the narrative of progress has always been as much an ethical position, a description of the way things ought to be, as it has been a description of the way they necessarily are. This has been the real American dream of progress, one always bigger than the country’s profoundly imperfect reality, one in which much of the world outside its borders has been able to find inspiration. Call me a product of my upbringing if you will, but it’s a dream to which I still wholeheartedly subscribe. To be a progressive is to recognize that the world is a better place than it used to be — that, by almost any measurement we care to take, human life is better than it’s ever been on this little planet of ours — thanks to those Enlightenment virtues of reason, science, humanism, and progress. And it is to assert that we have the capacity to make things yet much, much better for all of our planet’s people.

Progress will continue to be the binding theme of this series of articles, as it is the central theme of Civilization. We’ll continue to turn it around, to peer at it, to poke and prod it from various perspectives. Because ultimately, responsibility for our future doesn’t lie with some dead hand of historical or technological determinism. It lies with us, the strategizers sitting behind the screen, pulling the levers of our real world’s civilizations.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K a Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, The Past is a Foreign Country by David Lowenthal, The Human Use of Human Beings by Norbert Wiener, The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics by Christopher Lasch, History of the Idea of Progress by Ribert Nisbet, The Idea of Progress by J.B. Bury, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker, The End of History and the Last Man by Francis Fukuyama, A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr., Ulysses by James Joyce, Lectures on the Philosophy of History by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche, and The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; Computer Gaming World of September 1991 and December 1991; Popular Culture Review of Summer 2002.)