The hardest day that Ken Williams ever spent at the helm of Sierra On-Line was one in April of 1984. That was the day that, with cartridges full of the simple action games the venture capitalists had urged him to produce piling up in warehouses following the Great Videogame Crash and with red ink spilling everywhere, he was forced to let two-thirds of his employees go. In ten hours or so Sierra shrank from a company of 120 employees to one of 40. Always one to look another straight in the eye and tell it like it was — a quality that earned for him fantastic loyalty and even love amongst his charges — Ken sat in his office all day delivering the shattering news himself to shocked visage after shocked visage. He went home determined never to have another day like that again, never again to let the advice of others lead him to ruin. Love them or hate them for the strong opinions that their leader was never reluctant to express, no one would ever again be able to call Sierra a follower.

The most important lesson Ken took away from Sierra’s near-death experience was to be very choosy about what platforms he chose to support in the future. He had, for instance, decided that he had no use whatsoever for game consoles of any kind. For him, the consoles that had nearly become the death of his company reeked of snake oil and volatility, the computers that had birthed it of stability and sanity. Admittedly, at the time that Ken came to this conclusion it hardly stood out like it would in later years. In 1984, believing the time of the consoles to be done forever and foreseeing world domination on the horizon for home computers was very much the conventional wisdom. But the other major platform lesson that Ken had learned, or thought he’d learned, ran just as deep in his psyche but in a far more contrary direction: he had decided that not only the consoles but also the cheap home computers that were supposed to replace them were on the way out.

When one talked about a “cheap home computer” in the United States in 1984 one was almost invariably talking about the Commodore 64, which had just enjoyed an absolutely massive Christmas that made it the premier gaming platform in the country by a mile, a position it would hold firmly for another three or four years. Even when it became clear that the home-computer revolution at large was sputtering, the 64 remained the rock that sustained most of Sierra’s competitors. And yet already in 1984, when the 64 was just coming into its own, Ken Williams was making and following through on a decision to abandon it. A few more 64 titles would trickle out of Sierra over the next year or so, projects that had been in the works before the Crash or porting offers from third parties cheap enough to be worthy of a shrugged assent, but by and large Sierra was done with the Commodore 64 just when the rest of the industry was really waking up to it.

Ken’s loathing for the 64, which he dismissed as a “toy computer,” and its parent company, upon which he tended to bestow still choicer epithets, was visceral and intense. Commodore, just as much or more than Atari and Coleco, had loomed large over Sierra’s ill-fated foray into cartridge games. Many of the cartridges piled up in warehouses, threatening to smother Sierra under their storage costs alone, were for the 64’s older but weaker sibling, the VIC-20. Commodore had all but killed the VIC-20 software market overnight in 1983 when they’d unexpectedly slashed the price of the 64 so far that it didn’t make sense for computing families not to replace their old models with the shiny new one. In killing one of their own platforms without giving even an inkling of their plans for doing so, they’d left Sierra and many other publishers like them high and dry. Now it was 1984, Jack Tramiel was gone, and Commodore’s new management was claiming to be different. To at least some extent they really were earnestly trying to turn Commodore into a different sort of company, but it was all too little too late for Ken. He was done with fly-by-night operations like theirs. He believed that Sierra could hope to find truly safe harbor in only one place: inside the comfortingly bland beige world of IBM.

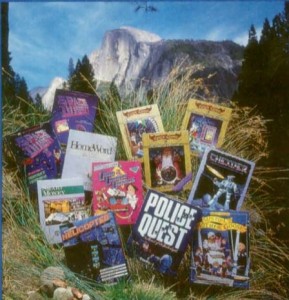

Sierra’s embrace of IBM might read as shocking, given that their own culture seemed the very antithesis of the crewcut-sporting, dark-suit-clad, company-theme-song-singing world of Big Blue. It’s certainly true that a big part of Sierra’s corporate personality was born from the last embers of the counterculture fire of the 1960s, which had managed to smolder for longer in California than just about anywhere else. Their hippie outlook was reflected not just in the image they preferred to project to the world, of a sort of artists commune tucked away in the bucolic wilderness near Yosemite, but also in a certain hedonistic spirit in which just about everyone, especially in the early days, indulged at least a little bit.

Yet there were also other, more conservative currents at work inside Ken and thus also inside Sierra. Ken had spent much of the 1970s as a jobbing programmer working not on the likes of the DEC PDP-10s, where creativity ran wild and so much hacker culture had been born, but on the machines that the industry referred to as the Big Iron: the huge, unsexy mainframes, all clattering punched cards and whirling reel-to-reel tapes and nerve-jarring industrial printers, that already by then underpinned much of the country’s industrial and financial infrastructure. This was the domain of IBM and the many smaller companies that orbited around it. Most hackers looked upon the mainframes with contempt, seeing only a hive mind of worker drones carrying out dull if necessary tasks in unimaginative ways. But Ken, especially after being dumped into the chaos that was the early PC market upon founding Sierra, saw stability and maturity there. Whatever else you could say about those machines, you knew they were going to be there next year and the year after and even the year after that. And you knew as well that, while IBM might move slowly and with infuriating deliberation, they were as close a thing to an irresistible force that the world of business had ever seen once set in motion. One bet against Big Blue only at one’s peril. And IBM was eminently predictable, a blessed trait in an emerging industry like the PC market. They were unlikely to suddenly undercut and destroy one of their platforms without giving all of their partners plenty of warning first. In short, IBM represented for Ken a legitimacy that the likes of Commodore and Atari and even Apple could never hope to match.

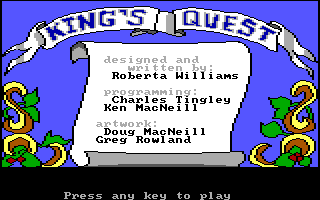

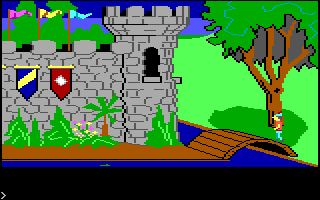

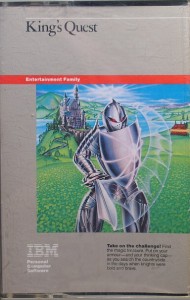

Adding to this was the fact that Sierra had had a surprisingly long and close relationship with IBM already, one that by all accounts had engendered a certain mutual trust and respect. IBM had first approached Sierra — not the other way around — in early 1981, just a few months after Ken and Roberta and brother John had packed up and moved out to Oakhurst to start their new company/artists commune in earnest. IBM was soon to introduce their first PC, to be known simply as the “IBM PC,” and they wanted Sierra to port a few of their Apple II hits — most notably their landmark illustrated adventure game The Wizard and the Princess — to their new platform in time for its launch. This Sierra did, thus beginning a steady and often fruitful relationship. IBM again came to Sierra for games and other software for their new home-oriented machine, the PCjr, in 1983. The PCjr turned into a flop, but not before IBM funded the development of Sierra’s revolutionary new AGI platform for making animated adventure games as well as the first game written with it, King’s Quest.

Thanks to its open, scrupulously documented hardware design and a third-party operating system that Microsoft was all too happy to sell to anyone who asked for a license, by 1984 clones of IBM’s PC architecture were sprouting up everywhere, just as they had in the mainframe industry in earlier decades. The IBM PC was fast leaving the nest, becoming a well-established hardware and software standard that could survive and develop independently of its parent, a unique phenomenon in the young industry. With so much of corporate America already wedded to that standard, Ken judged that it couldn’t die. More boldly, he also judged that sooner or later it would become the standard everywhere, not only in business but also in the home. The industry would need to settle on one platform across the board someday soon as software continued to grow more complex and porting it to half a dozen or more machines thus ever more costly. No platform was so well-positioned to become that standard as the IBM PC. In anticipation of that day, the IBM PC must be Sierra’s first priority from now on. Second priority would be given to the Apple II line, for which they still retained a lot of knowledge and affection even as the confused messaging coming out of Apple following the launch of the new Macintosh made them less bullish on it than they had been a year or two earlier. Everything else would be ignored or, at best, given much lower priority.

The decision managed to be simultaneously short-sighted and prescient. For many years to come Ken and his colleagues would look forward to every successive Christmas with no small sense of schadenfreude, certain that this simply must be the year that the idiosyncratic also-rans faded away at last and IBM’s architecture took over homes as it already had businesses. For quite some years they were disappointed. Commodore, after very nearly going under in early 1986, got a second wind and just kept on selling Ken’s hated 64s in absurd quantities. And yet more incompatible platforms appeared, like the Atari ST and Commodore’s new Amiga. Sierra somewhat begrudgingly ported their AGI interpreter to both, but, because the games took no advantage of these new machines’ much more advanced audiovisual capabilities, they weren’t generally well received there. For some it seemed that Ken was leaving millions on the table out of sheer stubbornness. Restless investors talked pointedly about “chasing pennies” in the clone market when dollars were ripe for the taking.

Yet in the end, if admittedly in a much later end than Ken had ever predicted, the IBM/Microsoft architecture did win out for exactly the reasons that Ken had said it must: not perhaps the most sexy or elegant on the block, it was nevertheless practical, reliable, stable, and open (or at least open enough). When the big break came, Sierra would be well-positioned with titles that supported the new sound cards, graphics cards, and CD-ROM drives that were making these heretofore dull machines enticing for homes at last, well-positioned to take a spot at the forefront of mainstream computer entertainment.

But that’s a story for later articles. What we’re interested in now is this interim period when Sierra, whilst waiting less than patiently for the clones’ breakthrough, found ways of sustaining themselves in markets ignored by just about everyone else. While the rest chased Commodore 64 owners, Sierra existed in splendid isolation in their own parallel universe. Happy as they were to sell their software through all of the usual gaming channels, far more was sold through shops dealing in IBMs and IBM-compatibles who mostly catered to business customers — but, hey, even businesspeople like to have fun sometimes. “It’s like we were dealing with a distribution channel that our competitors failed to even see was out there,” says John Williams. Still more important, the real key to their survival during these oft-lean years, was yet another alternate channel that even fewer others bothered to explore: Radio Shack.

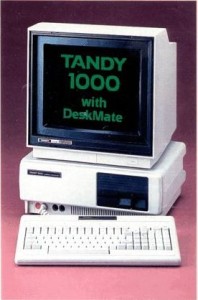

Like the clones that were also so important to Sierra, Radio Shack wasn’t the most exciting retailer in the world. In compensation they were, like IBM, stable and reliable, a quality that endeared them enormously to Ken. In fact, they were after his own heart in more ways than one. In late 1984, when Sierra was still teetering on the razor’s edge of bankruptcy, Radio Shack made a concerted and very clever attempt to succeed where IBM themselves had failed at making a PC clone that people would actually want to buy for the home. The Tandy 1000 was in some ways an outright PCjr copycat, incorporating its 16-color graphics capabilities and its three-voice sound synthesizer. Tandy, however, ditched the PCjr’s horrid keyboard, added a menu-driven shell on top of MS-DOS (“DeskMate”) to make it easier to use, and in general made a proper computer out of it, as expandable as any other clone and without all of the artificial constraints and bottlenecks that IBM had built into the PCjr to keep it from competing with their “big” machines. At about $1200 it was still much pricier than the likes of the Commodore 64, but it was also much more capable in most ways, able to handle typical productivity tasks with ease thanks to its 80-column display and its compatibility with the huge ecosystem of MS-DOS software. It was a very compelling product for a family looking for a somewhat serious computer that could also play games in reasonable style and that wouldn’t completely break the bank. A hit for Radio Shack, it became nothing less than Sierra’s savior.

To understand how that could be, you have to understand two things about Radio Shack. The first is that, while Radio Shack did sell some third-party software, their selection of same was far from overwhelming. What with Radio Shack not selling the more popular gaming machines like the Commodore 64 and being far from aggressive about seeking out software for their shelves, most publishers never really thought about them at all, or if they did concluded it just wasn’t worth the effort. The second salient point is that Radio Shack customers, especially those who splashed out on a big-ticket item like a computer system, were astonishingly loyal. Radio Shack was the dominant retailer in the rural United States, and even more so in the oft-forgotten markets of Canada and Australia. As John Williams once put it to me, “Every town in Canada and Australia had a Radio Shack, even if the only other retailer was a small grocery store.” Many a Radio Shack customer had literally no other option for buying software within fifty or even a hundred miles. Even those customers who lived a bit closer to the center of things often never seemed to realize that they didn’t have to buy software for their new Tandy 1000s from the meager selection on their local franchises’ shelves, that Babbage’s and Software, Etc. and ComputerLand and plenty of others had a much greater selection that would also work perfectly well. Whatever the reason, people who liked their local Radio Shack seemed to really like their local Radio Shack.

This combination of little competition on Radio Shack’s shelves and a captive audience to buy from them spelled gold for Sierra, who established a relationship with Radio Shack and made them a priority in exactly the way that virtually no one else in the industry was doing. Ken struck up a warm relationship early on with Radio Shack’s senior software buyer, a fellow named Srini Vasan, that went beyond that of mere business acquaintances to become a genuine friendship. The two came to trust and rely on each other to a considerable degree. Ken would call Srini before initiating a new project to see if it would “fit” with Radio Shack, and Srini in turn was occasionally willing to take a chance on something outside the partners’ usual bill of fare if Ken really thought it could become a winner. Srini also made sure that Sierra got pride of place in store displays and in the catalogs that Radio Shack shipped to all and sundry. By 1986 no less than one-third of Sierra’s revenue was coming through Radio Shack — the difference and then some between bankruptcy and a modestly profitable bottom line. Radio Shack proved such a cash cow that Sierra even violated Ken’s usual sense of platform priorities at Srini’s prompting to port some of their adventure games as well as other products to one of the Tandy marquee’s lower-end IBM-incompatible models, the Color Computer, where they were by all indications also quite successful.

Selling to the typical Radio Shack customer — rural, conservative, often religious — meant that the software Sierra moved through that pipeline had to be noncontroversial in every way, even more plainly G-rated than was the norm for the industry at large. So too the corporate image they projected in selling it. In this as in so much else Roberta Williams was a godsend. Just a few years on from posing as a topless swinger in a hot tub for the cover of Softporn, she was now an all-American Great Mom, the perfect ambassador to the Radio Shack demographic. Sierra took to featuring her picture — looking always friendly and wholesome and pretty — on the back of all her games, over a caption declaring that “her games have sold more copies than any other woman in computer software history” (a bit of tortured diction that did prove that their copywriting skills still weren’t quite on par with their abstract promotional instincts).

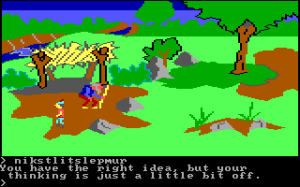

The products they were peddling through Radio Shack and elsewhere can be largely broken down into three categories: one well-remembered today, one only more vaguely recalled, and one virtually forgotten. Those that everyone remembers are of course the AGI-driven graphic adventures, which began with the first three of Roberta Williams’s long-running King’s Quest series, released in quick succession just a year apart from one another, and then gradually opened up as resources became less straitened to include alternative series like Space Quest. Paralleling these releases, and sometimes running under the same AGI engine, was a line of educational software that often used the classic Disney stable of characters. There was some conflation of these two product lines, particularly in the case of King’s Quest, which was often marketed as a family-friendly, vaguely educational adventure series suitable for the younger set and, again, perfect for the typical Radio Shack family. Finally came the forgotten products that were actually quite a useful moneyspinner in their day: Sierra’s line of home-oriented productivity software that had their HomeWord word processor and their Smart Money personal-finance package as its star attractions.

The Disney partnership fit well with the general image Sierra was projecting. After all, what could be more Middle American than Disney? That said, it’s very much a sign of the times that the deal was ever made at all. Sierra was just barely scraping by from week to week, hardly a huge media company’s ideal choice to become a major partner. But then the stock of Disney themselves was at the lowest ebb of its history, in the middle of a long trough between the death or retirement of Uncle Walt’s original Nine Old Men and the critical and commercial revival that was 1989’s The Little Mermaid. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Disney was also trying to fend off an ugly hostile-takeover bid from the predatory financier Saul Steinberg. Sierra actually bought the Disney license, with Disney’s tacit approval, from Texas Instruments, whose bid for world domination in home computers had been thoroughly cut off at the knees during 1983 by Jack Tramiel’s Commodore. Buying the preexisting contract from Texas Instruments allowed Sierra to dodge Disney’s usual huge upfront licensing fee, which they couldn’t possibly have paid. Nevertheless, Sierra paid dearly for the license on the back end via exorbitant royalties. Even at their lowest ebb Disney had a way of making sure that no one got rich off of Disney but Disney.

While Roberta Williams worked on the Disney products on and off when not busy with her King’s Quest games, Sierra’s principal Disney point man was a former musician, musical director, and music teacher with a ready laugh and a great gift for gab. His name was Al Lowe, and Ken Williams had already fired him once.

Lowe had first come to Sierra’s attention via a couple of self-published educational titles that he’d written on his Apple II using BASIC and Penguin Software’s ubiquitous Graphics Magician. Ken was so impressed by them that he took over the publishing of both, and also hired Al himself as a designer and programmer. Al learned assembly language at Ken’s insistence and wrote a children’s adventure game in it called Troll’s Tale, only to be fired after less than a year in the great purge of April 1984. But then, as a dejected Al was about to leave his office, Ken threw him a lifeline. As remembered by Al himself:

“I want you to work as an outside contractor. You write games, and I’ll pay you advances against future royalties instead of a salary. For accounting purposes, if you’re a salaried employee you’re an expense, but if I’m paying you advances against future royalties you’re a prepaid asset. It’ll make the books look better.”

In time Al Lowe would become more important to Sierra’s commercial fortunes and public image than any other member of their creative staff short of Roberta Williams.

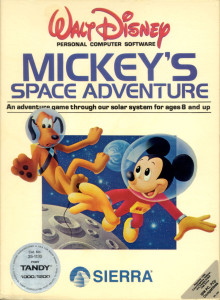

Like so much Sierra software, this copy of Mickey’s Space Adventure was sold through Radio Shack. Note the sticker at bottom left advertising Tandy 1000 compatibility.

But first there was Disney, who became a notable pain in the ass for him and everyone else who had to deal with them. Disney has always been known amongst their licensees as control freaks, but in this case they were control freaks who were also clueless. Responsibility for oversight of Sierra’s work ended up getting kicked down to their educational-films division, a collection of aged former schoolteachers who didn’t even know how to boot a computer yet were desperate to prove to their own managers that they were contributing. The problem was that their lack of understanding of the technology involved sharply limited how productive those contributions could be. For instance, Sierra’s artists were constantly being told that they needed to make Mickey Mouse’s ears “rounder” when it simply wasn’t possible; the pixels themselves were just too big and too square. Disney, says John Williams, “knew nothing about the media we were creating, didn’t care, and didn’t want to.” Al Lowe developed the most effective strategy for dealing with them: to ignore them as much as possible.

I would rarely send them anything unless they begged me for it, and I always made sure it took me a few extra days to get something ready for them. I basically played a passive-aggressive postponement game with them. And it worked out because they didn’t really have a lot of good suggestions. They often suggested changes so that they would have some imprint on the product, but their changes were never for the better. It was always just to make it different, so that they could say they’d done something.

The combination of Disney’s control-freak tendencies and their high royalties quickly soured everyone on the deal, iconic though the characters themselves may have been. In the end it resulted in only a handful of releases, including one each for Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, and Winnie the Pooh, with most activity stopping well before the license itself actually expired. The entire episode is dismissed by John Williams today as an “unproductive side trip,” while Ken Williams walked away from the Disney experience having learned yet one more lesson that he would use to guide Sierra from here on in a direction that was, once again, contrary to the way just about everyone else in the industry was going. From now on they would stay far, far away from licenses of any sort.

Perhaps the most worthwhile result of the partnership was a full-fledged AGI adventure game based on Disney’s 1985 box-office bomb The Black Cauldron that was largely designed by Roberta and programmed, as usual, by Al Lowe. Being designed to be suitable for younger children than even the King’s Quest games, it ditches the parser entirely in favor of a menu-driven interface and is nowhere near as cruel as the typical Sierra adventure game of the era. It would prove to be good training for Al’s next project.

The winding down of the Disney arrangement might have made Al Lowe nervous, may have made him wonder if it also meant the winding down of his career — or at least his career with Sierra — as a maker of games. If so, he didn’t have to be nervous very long. Soon after The Black Cauldron wrapped, Ken invited him to lunch to discuss a dangerous idea that had been brewing at the back of his mind for a while now, one that if carried through would send his new, family-friendly Sierra ricocheting back toward the debauchery of Softporn. We’ll join Al Lowe at that lunch, during which he’ll be introduced to the idea that will change his life forever, next time.

(This article is largely drawn from my personal correspondence with John Williams as well as interviews with Al Lowe conducted by Matt Barton, Top Hats and Champagne, and Erik Nagel. Last but far from least, Ken Gagne also shared with me the full audio of an interview he conducted with Lowe for Juiced.GS magazine. My huge thanks to John and Ken!)