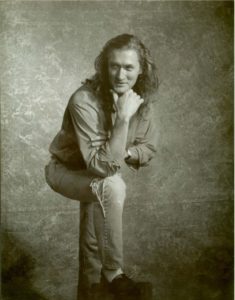

What happened for Ken and Roberta Williams in less than three years would have gone to anyone’s head. As the 1980s dawned, their lives were utterly ordinary. Ken was a business programmer putting in long hours every day in Los Angeles, Roberta his pretty, quiet, vaguely dissatisfied stay-at-home wife. Six months later she was a published game designer (to the extent that description meant anything in 1980), and the couple was sitting at their kitchen table opening the mail in disbelief as orders poured in for their little homemade adventure game. A year later, Ken was head of a burgeoning software house in their dream setting, nestled in the heart of the California Redwoods, and Roberta was his star designer. A year after that, they and the company they had built were software superstars. Glossy magazines and television shows begged for access and interviews; entertainment moguls flew them to New York to wine and dine them at 21 Club; venture capitalists lined up to offer money and advice, telling them they were at the forefront of the next big thing in media; big corporations offered to buy their whole operation, with starting offers of $20 million or more. Big franchises approached to talk about licensing deals: Jim Henson Associates, Disney, the Family Circus comic strip. For Ken, two of whose greatest heroes were Jim Henson and Walt Disney, such offers were flabbergasting. Late in 1982 IBM, by at least some measures the biggest, most powerful company in the world, humbly came knocking at the Williams’ door to ask if they’d be willing to work with them to develop software for their new home computer.

Yes, it would have gone to anyone’s head. Ken said yes to just about everyone, with the exception only of the outright buyout offers; he was having far too much fun to entertain them. The pundits, advisers, and investors that surrounded Ken were all telling him that the new low-cost home computers were the wave of the future, destined to replace the old Atari VCS game console and its competitors in the hearts and minds of consumers. This was the new gravy train, and the key to riding it was to get lots and lots of product out there to feed customers hungry for games for their new Commodore VIC-20s, Texas Instruments 99/4As, and Coleco Adams. Don’t stress too much about any given title, they said; just get lots of them out there. Simpler games were actually better, because then you could port them more quickly from platform to platform and pack them onto cartridges for all those ultra-low-end users without even a cassette drive. Ken, with these words ringing in his ears, dutifully made plans to push out 100 separate products in 1983 alone. He amassed a fleet of programmers to churn out action games which could be easily ported from platform to platform. Sierra spelled out this new approach in their “strategy outline” for 1983:

We believe the home-computer market to be so explosive that “title saturation” is impossible. The number of new machines competing for the Apple/Atari segment in 1983 will create a perpetually new market hungry for winning 1982 titles. We will exploit this opportunity.

Housing his growing fleet of salaried, workaday programmers — Ken had decided that dealing with artistically-tempered programmers like John Harris of Jawbreaker fame just wasn’t worth the trouble, that programming really shouldn’t be considered a creative endeavor at all — was soon becoming a problem. Growing technical, clerical, marketing, and warehouse staffs were also pushing the company’s total head count rapidly toward 100. Thus when the developer who owned Sierra’s office facilities offered to build a brand new building to house the company, a lovely place which perfectly suited the company’s image (if not, increasingly, its reality) as a clan of computer artisans living in the woods, Ken happily acquiesced, accepting rent in the vicinity of $25,000 per month.

The new offices weren’t the only building contract Ken signed around this time. Figuring that if they were going to be entertainment moguls they needed to live the part, Ken and Roberta hired an architect to design a sprawling 10,000 square-foot, $800,000 house — huge money in this rural area — on the Fresno River, complete with racquetball and volleyball courts, full-length wet bar, and a mini-arcade with all the latest games.

But by the time Ken and Roberta moved on Labor Day weekend, 1983, the fantasy of their lavish housewarming party, which included a professional comedy troupe brought in from San Francisco for the occasion, was undercut by some slowly dawning realities. Sierra’s first big partnership with Big Media, on the Dark Crystal game, had been a major artistic and commercial disappointment, done in by the tired old Hi-Res Adventure engine that powered it and a rote design by a Roberta Williams who seemed determined not to grow past what she had done for Mystery House. Their one real hit of the year, meanwhile, had not been any of the titles from Ken’s new programmers, but rather John Harris’s loving, officially licensed port of the arcade game Frogger, a port done so well that some said it surpassed its inspiration. Alas, Frogger was the last game Harris did for Sierra; he had left some time before, having signed on with Synapse Software, whom he considered more quality-oriented. It was already beginning to dawn at that party that they might actually make less this year than they had the last even as the new building and growing staff had increased their expenses enormously. Soon after, things really started to go south.

Much of the software that Sierra was now producing was on cartridges, which were both more expensive to produce than disks or tapes and took much longer to duplicate. With much of the industry following Sierra’s plan of churning out new games practically by the dozen, production capacity at the relatively limited number of facilities capable of making cartridges was at a premium. Sierra was forced to place huge orders in June or July for the games they hoped to be selling huge numbers of come Christmas. But a funny thing happened during the six months in between: the market for the VIC-20, the TI 99/4A, and the Coleco Adam, the machines for which most of these cartridges were produced, collapsed. Jack Tramiel, you see, had won the Home Computer Wars of 1983 by then, driving TI right out of the market. In the process, he had just about killed his own VIC-20 as well; the price of the vastly more desirable and capable Commodore 64 had dropped so low that there was little point in buying a VIC-20 instead. As for the Adam… well, it never had a chance; by the time it arrived the war was largely over and the victor already determined. The Commodore 64 rocketed out of that Christmas the new center of the gaming universe, a position it would hold for the next several years. Yet all Sierra had to sell Commodore 64 owners were a few simple games ported from the VIC-20. And they had tens of thousands of cartridges, millions of dollars of inventory which they couldn’t move for ten cents on the dollar, sitting in warehouses. Meanwhile their shiny licensing deals were also turning out to be of little benefit to the bottom line. Sierra felt that they were doing all the work on these and all the profits — what little there sometimes were — were going to the licensees. As 1984 ground on, it became clear that the company was in the most dire of straits, unable to even make their mortgage payments on their fancy new office building.

The only thing to do was to start cutting. In a matter of days the company shed the extra skin it had built up, going from 100 employees to an absolutely essential core of about 20. A desperate Ken went to Sierra’s landlord and offered him a 10% share in the company if he would just forgive them the rent for a few months, while they got back on their feet. Figuring that 10% of a dead company was worth less than the rent he might be able to get out of them now, he said no thanks. In the end Ken was able to negotiate only to give back some of the building for other tenants. He and Roberta and their closest associates paid some of the remaining rent for a while using second mortgages and personal credit cards. It looked like this dream they had been living was about to end less than four years after it had begun, that soon they might end up right back where they had started in the suburbs of Los Angeles. They might have packed it in but for one remaining hope: that contract they had signed with IBM back in the halcyon days.

Sierra’s relationship with IBM actually went back even further than that contract. IBM first partnered with Sierra during the run-up to the original IBM PC’s launch in 1981, when they hired them to port The Wizard and the Princess, one of the biggest Apple II titles of that year, to their new machine. Sierra first experienced the legendary IBM secrecy then. Prototypes would arrive in X-ray-resistant lead chests sealed with solder, and were expected to be stored and used in windowless rooms that were to be kept locked at all times. Despite being a relatively minor part of the PC’s launch, Sierra, and Ken in particular, got on well with IBM. For all the party-hearty persona Ken could put on (as well described in Hackers and elsewhere on this blog), he had spent his previous life working for big technology companies like IBM. He understood how they worked, knew what it meant to shake down a new computer system and find the bugs and flaws while also obeying the rules of corporate hierarchy. IBM likely found him a refreshing change from both the un-technical MBAs and the technically masterful but socially unsophisticated hackers that were most of his peers. At any rate, they came back to Sierra soon after initiating the PCjr project.

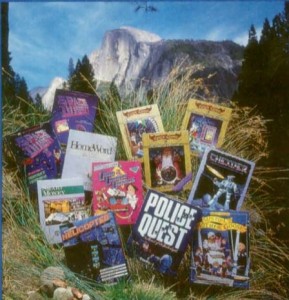

IBM flew Ken and Jeff Stephenson, the man who was quickly assuming Ken’s role as hacker in chief at Sierra as Ken got more and more absorbed with the business side, out to their offices in Boca Raton, Florida. After the NDAs and other legal niceties that were part and parcel of dealing with IBM, they explained what the PCjr was to be and asked them to pitch some software that might make a good fit. Ken and Jeff made a number of proposals that were accepted, including HomeWord, an easy-to-use, casual word processor with an early graphical user interface of sorts which Ken and Jeff were already working on; it would wind up IBM’s official word processor for the PCjr. But the most important proposal, the biggest in the history of Sierra On-Line and one which would change adventure gaming forever, was made up on the fly, drawn up on the back of a napkin during a pause in the proceedings.

Sierra was still known most of all for their Hi-Res Adventure line of illustrated adventure games. Unsurprisingly, IBM very much wanted something along those lines for the PCjr. But they had some specific requests for changes from Sierra’s traditional approach, which if nothing else proved that not everyone at IBM was as blissfully ignorant of gaming as legend would have it. They asked for a game that could be replayable, that would be more dynamic and complex in its world modeling, sort of like Ultima and Wizardry (adventures and CRPGs were not yet clearly defined separate genres at this point). They specifically asked that puzzles have multiple solutions, that there be many different possible paths through the game.

Ken and Jeff sensed that they really wanted Sierra to push themselves, to get beyond the tried-and-true Hi-Res Adventure model. And with good reason: as the sales for The Dark Crystal were about to show, Sierra desperately needed to raise their game if they wanted to keep their hand in adventures at all. Next to the games that Infocom was putting out, the Hi-Res Adventure games were painfully primitive. Yet how should they try to compete? Most other publishers, witnessing Infocom’s success with pure text, were beginning to shift their emphasis back to the parsers and the writing, de-emphasizing their pictures or removing them entirely. Infocom, in other words, was replacing Sierra as the model to be emulated. Ken instinctively sensed that this was not the right bandwagon for Sierra to leap aboard, much as they respected the technical accomplishment in Infocom’s games. They were movie people rather than book people; as Ken later said, Sierra had a “mass-market” sensibility which contrasted with Infocom’s “cerebral” approach. Rather than try to ape Infocom like other publishers, why not zig while everyone else zagged, double down on graphics while de-emphasizing text? Besides, one of the main selling features of the PCjr was to be its bright 16-color graphics. Shouldn’t its showcase adventure take advantage of them?

When IBM joined them again in the conference room, Ken and Jeff made their pitch for a new type of adventure game. Most of the screen would be given over to the graphics, like in the Hi-Res Adventures, but the interactivity would now also extend to this part of the display. The player’s avatar would be visible onscreen, with the player able to move him around within each room using a joystick or the arrow keys. The player would still have to type non-movement commands, but now positioning within each room would play an important role: you would have to move right up next to that old tree stump to peer inside, walk up to the kindly forest elf to talk to him, etc. Some text would still have to remain to explain some of what happened, but much of the experience would be entirely visual, more movie than book. Action sequences requiring precise timing and coordination could be introduced. The system also promised to introduce the kind of dynamism that IBM desired in other ways. Other characters and creatures could wander the world, to be dodged, fought, or befriended. What we would today call emergent behavior might arise: the player might hide behind a handy tree when the wicked witch suddenly popped onto the scene. It would be a showstopper, conforming to Ken’s ten-foot rule for software marketing while also introducing whole new tactical layers that had never been seen in adventure games before. IBM signed on happily.

The reaction in Oakhurst was not quite so enthusiastic. Some felt that Ken and Jeff had promised IBM the moon, that this was simply a leap too far. Perhaps remembering Sierra’s last two adventure games, both of which had gone through long, painful development cycles for little commercial reward, they pointedly suggested that Ken go back to IBM and explain that Sierra had bitten off more than they could chew, cut the proposal down dramatically to something more realistically achievable, and try to get IBM to accept it. Ken, realizing that any such action would destroy his credibility with IBM forever, absolutely refused. He pointed out that they had 128 K of memory to work with for this project, a huge figure in comparison to the 48 K they’d had for the Hi-Res Adventure games. He found a critical ally in Roberta, the person who would have to actually design for the system. She simply asked questions until she felt she understood the system and what it would and would not be capable of, digested IBM’s desires for a more dynamic game than was her previous wont, then went to work. Eventually the grumbling mostly ceased and the rest of the staff followed her example.

What with Ken having a company to run, the heavy lifting of turning the proposal into a game engine largely fell to Jeff Stephenson. Just like the Hi-Res Adventure engine, this one was designed to be reusable and extendible from the start. It was initially known as the Game Adaptation Language, or GAL. Ken, however, loathed the cutesiness of that acronym, and it was eventually renamed to the Adventure Game Interpreter, or AGI. (I’ll refer to the system as AGI from here on for the sake of consistency.) Soon the trucks bearing the familiar lead-lined crates began arriving in Oakhurst again, and development began in earnest on both the engine and the game it would run. The team chosen for the task consisted of Roberta and about half a dozen programmers and artists. The PCjr projects as a whole, which included the adventure game, HomeWord, and several other pieces of software, were given a top-secret code-name: Project Siesta. Still, it’s hard to keep anything a secret in a city as small as Oakhurst. Word quickly spread: “The big fucking company is in town again.”

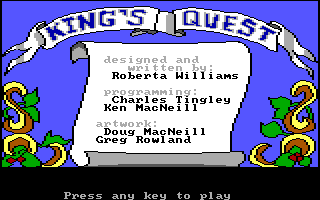

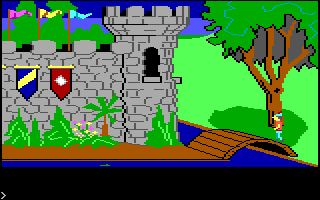

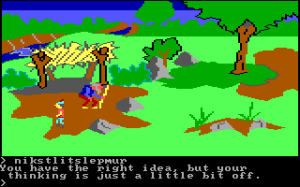

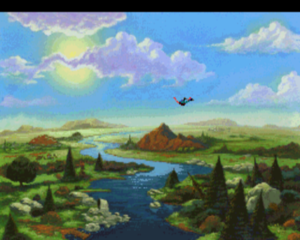

Some of the process of developing the first AGI game, eventually to be named King’s Quest, was not that far removed from the days of Hi-Res Adventure. The artists still drew each scene on paper using colored pencils. These drawings were then traced using a graphics tablet connected to a computer, where they were stored using the vector-graphics techniques Ken had developed back in the days of Mystery House and The Wizard and the Princess. (When playing King’s Quest on older, slower hardware you can see each new room being drawn in line by line. Fascinatingly, what you are actually seeing there are the motions of the stylus being guided by the person who first traced the image all those years ago. Early King’s Quest versions let you see the process more clearly via an undocumented “slow draw” mode that can be activated by pressing Control-V.) Thanks to this evergreen technique, the image of each room occupies only .5 to 2.5 K. The same data also tells the interpreter where Sir Graham, [1]In the very early versions of King’s Quest, Sir Graham’s name was spelled as “Grahame.” the game’s protagonist, can and cannot walk. Boundaries, such as the castle walls you see in the screenshot above, were traced with a special flag activated and incorporated right into the image itself.

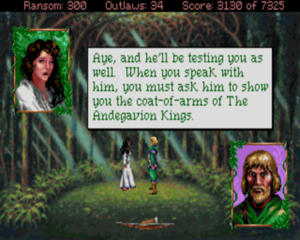

Perhaps the trickiest problem that Jeff Stephenson had to wrestle with stems from the fact that we view each room in the game from a parallel perspective. Thus the game needs to account for the z-axis in addition to the x- and y-axes to maintain the illusion of depth. Each object in each room is therefore given something Jeff called its “priority,” essentially its position on the Z-axis. An object’s priority can range from 1 to 15, and increases as it gets closer to the “back” of the room. In drawing a scene, the interpreter draws objects of lower priority after those of higher priority. Say that a tree is positioned on the screen at priority 9. If Graham moves vertically, “deeper” into the screen, to, say, priority 11, then moves horizontally “behind” the tree, the tree will conceal him as expected. Up to four moving characters can be in a single room, the interpreter constantly adjusting the onscreen image to account for their movements.

The game logic is described using a simple scripting language which is once again descended from the system Ken had developed for the Hi-Res Adventure line. Let’s take a look at one small piece of the scene shown above. In addition to our alter ego Graham, it shows a goat — “object” number 14 — who wanders back and forth in his corral, which in turn spans two rooms, numbers 10 and 11; the room shown above, the leftmost, is room 10. The goat continues to wander unless and until he is tempted to join Graham by a scrumptious-looking carrot. Here’s how the goat’s logic in room 10 is described in AGI:

IF HAS-GOAT 0 AND OBJHIT-EDGE 14 AND EDGE-OBJ-HIT 1 AND GOAT-GONE 0 AND SHOW-CARROT 0 THEN ASSIGN GOAT-ROOM 11, ERASE 10

So, and without getting too lost in the weeds here, if we do not “have” the goat and are not showing him the carrot, and the goat has hit the edge of the screen in his wanderings, remove (“erase”) him from room 10 and put him in room 11. Room 10 alone has 180 such lines of script to describe all of its interactive possibilities. Like most software, an AGI game is more complex than it looks. This is true from the standpoint of both the engine programmers and the scripters. In the context of its time, AGI is nothing less than a stunning technological tour de force — one which, like all the best software, looks easy.

The technical virtuosity on display here made it rather easy for reviewers of the time to lose sight of the actual game it enabled, a painfully common phenomenon in the field of videogames. Indeed, I was anticipating reviewing King’s Quest more as a piece of technology than an adventure game, particularly given that I frankly don’t think very highly of Roberta’s work on the Hi-Res Adventure line. I was, however, pleasantly surprised by her work here. King’s Quest‘s plot is almost as basic as that of the original Adventure: the kingdom of Daventry is in some sort of vaguely defined trouble, and the aging King Edward needs you, the brave knight Sir Graham, to find three magic items that can save it. Since he conveniently has no heirs, do that and “the throne will be yours.” King’s Quest is another treasure hunt, nothing more or less.

Still, and making allowances for the newness of the technology, Roberta does a pretty good job with it. Many of the characters and situations you encounter as you roam Daventry are drawn, and not without a certain charm, from classic fairy tales: Hansel and Gretel, Jack and the Beanstalk, Rumpelstiltskin. The latter is at the core of the one howlingly awful puzzle in the game, which starts out dodgy and just keeps layering on the complications until it’s well-nigh impossible.

(For the record: you meet an old gnome-looking sort of fellow who gives you three chances to guess his name. If you’re familiar with your Brothers Grimm, you might divine that he’s Rumpelstiltskin given the fairy-tale characters everywhere else in the game. But, no, “That is very close but not quite right.” Okay, you do have a note you found elsewhere which says, “Sometimes it is wise to think backwards.” So, “nikstlitslepmur.” No — “You have the right idea, but your thinking is just a little bit off.” It turns out you have to write the name using a backwards alphabet.)

But even here the IBM design brief saves Roberta from her worst instincts. There is, thank God, an alternate way to proceed without solving this puzzle, even if it does cost you some points. And most of the other puzzles are… not that bad, actually. Some are even pretty clever. That may sound like damning with faint praise, but given some of the absurdities of Time Zone it’s nevertheless praise indeed. There are a huge number of ways to go through King’s Quest, what with all of the alternate solutions on offer, and the game feels consciously designed in a holistic sense in a way that no previous Roberta Williams game did.

King’s Quest also makes use of most of the new possibilities afforded by the AGI system. There are enemies to be dodged and eventually dispatched — the witch out of Hansel and Gretel is particularly harrowing — and tricky action sequences to be navigated. King’s Quest is mostly a competent, enjoyable game even when divorced from its place in history as the first use of the revolutionary technology that powers it. It’s also reasonably solvable, at least if you aren’t too fixated on getting the maximum possible points. Realistically, it needed to be no more than a technological proof of concept to be a bestseller, but it manages to be considerably more than that. It acquits itself very well overall as the herald of a new paradigm for adventure gaming.

As development continued and Sierra’s financial position began to look more precarious, stress began to mount. Ken’s wish to just find average and uncreative but reliable programmers was perhaps amplified more than ever by some of the characters he ended up having to assign to the King’s Quest project. Whether because of its location near the old hippie meccas of northern California or just something in the water, Sierra always seemed to be filled with eccentrics despite Ken’s best efforts to run a more buttoned-down operation. One fellow was particularly noted for his acid consumption and his fascination with Fozzy Bear, and looked freakish enough that (in John Williams’s words) “when he went into a restaurant, everyone looked at him.” Another, similarly “off” programmer acted like a cross between a mad scientist and Zaphod Beeblebrox of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame. Near the end of the project one developer, angry at the long hours he had been working, held a critical piece of code ransom until Sierra paid him for dozens of hours of overtime to which he felt entitled. They agreed to pay, got the code, and promptly reneged, citing a clause in American contract law which says that a contract is null and void if one of the parties signs under duress.

When IBM officially unveiled the PCjr and its horrid Chiclet keyboard in November of 1983, Sierra was as surprised as anyone. For all their involvement in the machine’s development, they never had access to a real production model. Ken had to go down to ComputerLand and buy his own, just like everyone else, when the PCjr shipped at last in March of 1984. His first machine didn’t remain in his possession for very long. He went to the movies on his way home, leaving it in his car, only to find it stolen when he returned. That must have seemed like a bad omen coming to fruition as it became more and more clear that the PCjr, seemingly Sierra’s last hope, was flopping in the marketplace.

And that must have seemed a double shame because — and I know I may seem to be belaboring the point, but I can hardly emphasize this enough — King’s Quest was amazing in its time. Even magazines devoted to other platforms felt compelled to talk about it; it was just that revolutionary. King’s Quest, marketed under IBM’s official imprint with cover art apparently drawn by someone who had never seen the game, did sell pretty well by the standards of IBM PCjr software, but there just weren’t enough PCjrs being sold to save Sierra. Similarly, a version for the PCjr’s bigger brother, the IBM PC, sold well by the standards of games for that platform, but the entertainment market for such a business-computing stalwart wasn’t up to much. Although the AGI system had been designed to be portable, it had also been designed to run in 128 K of memory. This locked it out of the typical unexpanded Apple IIe (64 K) and the biggest gaming platform in the country, the Commodore 64. Sierra had exactly the right game on exactly the wrong platform. It seemed Ken had backed the wrong horse, a final bad decision that looked to have doomed his company. The situation just got more and more desperate. John Williams, Sierra’s marketing director, recalls placing media buys around this time with no idea how he was going to pay for them when the invoices came due: “This is either going to help, in which case we can deal with the cost of these and maybe negotiate payment on it — or it won’t work and we’ll be gone” anyway.

Two new machines played a big role in saving Sierra. Just a month after the PCjr finally shipped to stores, Apple announced and shipped the fourth incarnation of the Apple II, the IIc. We’ll talk a bit more about it in a future article, but for now suffice to say that the IIc was designed to be a semi-portable, closed appliance computer, in contrast to the hacker’s laboratories that had been previous Apple II models. Most critically for our purposes today, the IIc shipped with 128 K of memory. Its commercial performance would ultimately be rather lukewarm, but it did prompt many users of the older IIe model to upgrade to (at least) 128 K to match its capabilities. In time there were enough 128 K Apple IIs to justify porting the AGI interpreter to the platform.

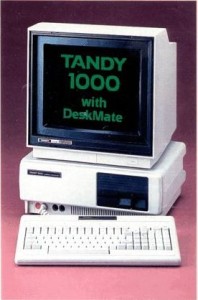

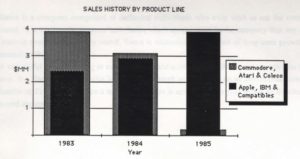

But it was the Tandy 1000 that really saved Sierra in the most immediate sense, that gave that critical mass of 128 K Apple II users time to amass. It was introduced just as 1984, the most difficult year in Sierra’s history, was winding down. In many ways it was what the PCjr should have been, with the same graphics and sound capabilities and IBM PC compatibility in a smarter, more usable and expandable package. And it was sold in Radio Shack stores all over the country. In some areas the local Radio Shack was the only place within 200 miles to buy a computer. Sierra smartly developed a strong relationship with Radio Shack in the wake of the Tandy 1000’s announcement. Few other software publishers bothered, meaning that King’s Quest and other Sierra games stood almost alone on the shelves in many of these captive markets. The Tandy 1000, combined with the slowly increasing user base of expanded Apple IIs, gave King’s Quest the opportunity to slowly pull Sierra back from the edge of the abyss, particularly since much of the game’s $850,000 development cost had been funded by IBM. It would take time, but by the end of 1985, with King’s Quest II now already out and doing very well, the company was paying off debts and beginning to grow again.

Ken, Roberta, John, Jeff, and their closest associates had, much to their credit, stuck to their guns and not made the perfectly reasonable decision to pack it in. But they had also, as Ken well realized, gotten very, very lucky. Without the Tandy 1000 and few other lucky breaks, Sierra could easily have gone the way of Adventure International, Muse, and other big software houses who were flying high in 1982 and dead in 1985. As he recently said, it had all been “fun and games” for the first few years. Now he understood how quickly things could go bad with a few wrong decisions, understood what a fragile entity Sierra really was. Most of all, he never wanted to go through another year like 1984 again. The Ken Williams that emerged from that period was, like his company, changed. From now on he would do a remarkable job of balancing ambition with caution. This capacity to change and learn from his mistakes, much rarer than it seems it ought to be, was perhaps ultimately the most important quality he brought to Sierra. He reoriented his company to stop chasing fast bucks and to focus on a smaller number of quality titles for a modest number of proven platforms, and accumulated a stable of designers, programmers, and artists whom he treated with respect. They in turn did good, occasionally great work for him. Sierra Mark II, leaner, humbler, and wiser, was off and running.

(My huge thanks once again go to John Williams for contributing so many of his memories to this article. Hackers by Steven Levy was also invaluable for what I believe will be the last time at last, as we’ve now moved beyond the period it covers. An article in the February 1985 Compute! breaks down the AGI system in unusual detail for a contemporary source. If you want to know more about its technical side, it’s been documented in exhaustive detail since. If you just would like to play King’s Quest, it’s available in a pack with King’s Quest II and III at Good Old Games.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | In the very early versions of King’s Quest, Sir Graham’s name was spelled as “Grahame.” |

|---|