(As the name would indicate, this article marks a belated continuation of my series about the life and times of Microsoft Windows. But, because any ambitious dive into history such as this site has become is doomed to be a tapestry of stories rather than a single linear one, this article and the next couple of them will also pull on some of the other threads I’ve left dangling — most obviously, my series on the origins of the Internet and the World Wide Web, on the commercial online networks of the early personal-computing era, and on the shareware model for selling software online and the changes it wrought in the culture of gaming in particular. You might find some or all of the aforementioned worthwhile to read before what follows. Or just dive in and see how you go; it’s all good.)

For the vast majority of us in the PC software business, it’s important to realize that systems such as Windows 95 will be important and that systems such as Windows NT won’t be. Evolutionary changes are much easier for the market to accept. For a revolutionary upset to be accepted, it must be an order of magnitude better than what it seeks to replace. Not 25 percent or 33 percent better, but at least ten times better. Otherwise, change had better be gradual, like Windows 95. Products such as NT speak to too small a niche to be interesting. And even the NT sales that do occur don’t lead anywhere: right now I’m running on a network with an NT server, but no software is ever likely to be bought for that server. It sits in a closet that no one touches for weeks at a time. This is not the sort of platform on which to base your fortune.

If you’re choosing platforms for which to develop software, remember that what ultimately matters is not technical excellence but market penetration. The two rarely go hand-in-hand. This is not simply a matter of bowing to the foolish whims of the market, however: market penetration leads to standardization, and standards have tangible benefits that are more important than the coolest technical feature. Yes, Windows 95 still uses MS-DOS; no, it’s not a pure Win32 system; no, it’s not particularly integrated; no, it hasn’t been rewritten from the ground up; and yes, it is lacking some nice features found in Windows NT or OS/2. But none of these compromises will hurt Windows 95’s chances for success, and some will actually help make Windows 95 a success. Windows 95 will be the standard desktop-computing platform for the next five years, and that by itself is worth far more than the coolest technology.

— Andrew Schulman, 1994

In July of 1992, Microsoft hosted the first Windows NT Professional Developers Conference in San Francisco. The nearly 5000 hand-picked attendees were each given a coveted pre-release “developer’s version” of Windows NT (“New Technology”), the company’s next-generation operating system. “The major operating systems of today, DOS and Windows, were designed eight to twelve years ago, so they lie way behind our current hardware capabilities,” said one starry-eyed Microsoft partner. “We’ve now got bigger disks, displays, and memory, and faster CPUs than ever before. As a true 32-bit operating system, Windows NT exploits the power of the 32-bit chip.” Unlike Microsoft’s current 3.1 version of Windows and its predecessors, which were balanced precariously on the narrow foundation of MS-DOS like an elephant atop a lamp pole, Windows NT owed nothing to the past, and performed all the better for it.

But what follows is not the story of Windows NT.

It is rather the story of another operating system that was publicly mentioned for the very first time in passing at that same conference, an operating system whose user base over the course of the 1990s would eclipse that of Windows NT by a margin of about 50 to 1. Microsoft was calling it “Chicago” in 1992. The name derived from “Cairo,” a code name for a projected future version of Windows NT. “We wanted something between Seattle” — Microsoft’s home metropolitan area, which presumably stood for the current status quo — “and Cairo in terms of functionality,” said a Microsoft executive later. “The less ambitious picked names closer to Seattle — like Spokane for a minor upgrade, all the way to London for something closer to Cairo.” Chicago seemed like a suitable compromise — a daunting distance to travel, but not too daunting. The world would come to know the erstwhile Chicago three years later as Windows 95. It would become the most ballyhooed new operating system in the entire history of computing, even as it remained a far more compromised, less technically impressive piece of software architecture than Windows NT.

Why did Microsoft split their efforts along these two divergent paths? One answer lay in the wildly divergent hardware that was used to run their operating systems. Windows NT was aimed at the latest and the greatest, while Chicago was aimed at the everyday computers that everyday people tended to have in their offices and homes. But another reason was just as important. Microsoft had gotten to where they were by the beginning of the 1990s — to the position of the undisputed dominant force in personal computing — not by always or even usually having the best or most innovative products, but rather by being always the safe choice. “No one ever got fired for buying IBM,” ran an old maxim among corporate purchasing managers; in this new era, the same might be said about Microsoft. Part of being safe was placing a heavy emphasis on backward compatibility, thus ensuring that the existing software an individual or organization had gotten to know and love would continue to run on their shiny new Microsoft operating system. In the context of the early 1990s, this meant, for better or for worse, continuing to build at least one incarnation of Windows on top of MS-DOS, so that it could continue to run even a program written for the original IBM PC from 1981. Windows NT broke that compatibility in the name of power and performance — but, if getting that 1985-vintage version of WordPerfect up and running was more important to you than such distractions, Microsoft still had you covered.

Which isn’t to say, of course, that Microsoft wouldn’t have preferred for you to give up your hoary old favorites and enter fully into the brave new Windows world of mice and widgets. They had struggled for most of the 1980s to make Windows into a place where people wanted to live and work, and had finally broken through at the dawn of the new decade, with the release of Windows 3.0 in 1990 and 3.1 in 1992. The old stars of MS-DOS productivity software — names like the aforementioned WordPerfect, as well as Lotus, Borland, and others — were scrambling to adapt their products to a Windows-driven marketplace, even as Microsoft, whose ambitions for domination knew few bounds, was driving aggressively into the gaps with their own Microsoft Office lineup, which was tightly integrated with the operating system in ways that their competitors found difficult to duplicate. (This was due not least to Microsoft’s ability to take advantage of so-called “undocumented APIs,” hidden features and shortcuts provided by Windows which the company neglected to tell its competitors about — an underhanded trick that was an open secret in the software industry.) By the summer of 1993, when Windows NT officially debuted with very little fanfare in the consumer press, Windows 3.x had sold 30 million copies in three years, and was continuing to sell at the healthy clip of 1.5 million copies per month. Windows had become the face of computing as the majority of people knew it, the MS-DOS command line a dusty relic of a less pleasant past.

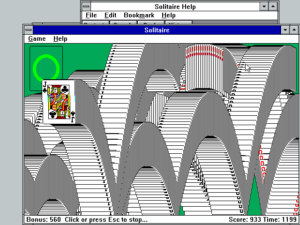

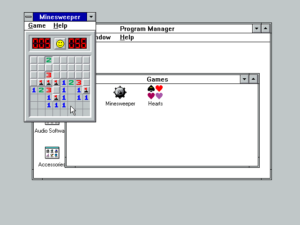

With, that is, one glaring exception that is of special interest to us: Windows 3 had never caught on for hardcore gaming, and never would. Games were played on Windows 3, mind you. In fact, they were played extensively. Microsoft Solitaire, which was included with every copy of Windows, is almost certainly the single most-played computer game in history, having served as a distraction for hundreds of millions of bored office workers and students all over the world from 1990 until the present day. Some other games, generally of the sort that weren’t hugely demanding in hardware terms and that boasted a fair measure of casual appeal, did almost equally well. Myst, for example, sold an astonishing 5 million or more copies for Windows 3, while Microsoft’s own “Entertainment Packs,” consisting mostly of more simple time fillers much like Solitaire, also did very well for themselves.

But then there were the hardcore gamers, the folks who considered gaming an active hobby rather than a passive distraction, who waited eagerly for each new issue of Computer Gaming World to arrive in their mailbox and spent hundreds or thousands of dollars every year keeping the “rigs” in their bedrooms up to date, in much the same way that a previous generation of mostly young men had tinkered endlessly with the hot rods in their garages. The people who made games for this group told Microsoft, accurately enough, that Windows as it was currently constituted just wouldn’t do for their purposes. It was too inflexible in its assumptions about the user interface and much else, and above all just too slow. They loved the idea of a runtime environment that would let them forget about the idiosyncrasies of 1000 different graphics and sound cards, thanks to the magic of integrated device drivers. But it had to be flexible, and it had to be fast — and Windows 3 was neither of those things. Microsoft admitted in one of their own handbooks that “game graphics under Windows make slug racing look exciting.”

One big issue that game developers had with Windows 3 for a long time was that it was a 16-bit operating system in a world where even the most ordinary off-the-shelf computer hardware had long since gone 32 bit. The largest number that can be represented in 16 bits is 65,535, or 64 kilobytes. A 16-bit program can therefore only allocate memory in discrete segments of no more than 64 K. This became more and more of a problem as games grew more complex in terms of logic and especially graphics and sound. MS-DOS was also 16-bit, but, being far simpler, it was much easier to hack. The tools known as “32-bit DOS extenders” did just that, giving game developers a way of using 32-bit processors to their maximum potential more or less transparently, with a theoretical upper limit of fully 4 GB per memory segment. (This was, needless to say, much, much more memory than anyone actually had in their computers in the early 1990s.) Ironically, Windows 3 itself depended on a 32-bit DOS extender to be able to run on top of MS-DOS, but it didn’t extend all of its benefits to the applications it hosted. That did finally change, however, in July of 1993, when Microsoft released an add-on called “Win32S” that did make it possible to run 32-bit applications in Windows 3 (including many applications written for Windows NT).

That was one problem more or less solved. But another one was the painfully slow Windows graphics libraries that served as the intermediary between applications software and the bare metal of the machine. These were impossible to bypass by design; one of the major points of Windows was to provide a buffer between applications and the hardware, to enable features such as multitasking, virtual memory, and a consistent look and feel from program to program. But game developers saw only how slow the end result was. The only way they could consider coding for Windows was if Microsoft could provide libraries that were as fast — or at least 90 percent as fast — as banging the bare metal in MS-DOS.

In the meantime, game developers would continue to write for vanilla MS-DOS and to sweat the details of all those different graphics and sound cards for themselves, and the hardcore gamers would have to continue to spend hours tweaking memory settings and IRQ addresses in order to get each new game they bought up and running just exactly perfectly. Admittedly, some gamers did consider this almost half the fun, a talent for it as much a badge of honor as a high score in Warcraft; boys do love their technological toys, after all. Still, it was obvious to any sensible observer that the games industry as a whole would be better served by a universal alternative to the current bespoke status quo. Hardcore gamers made up a relatively small proportion of the people using computers, but they were a profitable niche, what with their voracious buying habits, and they were also trail blazers and influencers in their fashion. It would seem that Microsoft had a vested interest in keeping them happy.

Windows NT might sound like the logical place for such early adopters to migrate, but this was not Microsoft’s view. “Serious” users of computers in corporate and institutional environments — the kind at which Windows NT was primarily targeted — had a long tradition of looking down on computers that happened to be good at playing games, and this attitude had by no means disappeared entirely by the early 1990s. In short, Microsoft had no wish to muddy the waters surrounding their most powerful operating system with a bunch of scruffy gamers. Games of all stripes were to be left to the consumer-grade operating systems, meaning the current Windows 3 and the forthcoming Chicago. And even there, they seemed to be a dismayingly low priority for Microsoft in the eyes of the people who made them and played them.

This doesn’t mean that there was no progress whatsoever. By very early in 1994, a young Microsoft programmer named Chris Hecker, working virtually alone, had put together a promising system called WinG, which let Windows games and other software render graphics surprisingly quickly to a screen buffer, with a minimum of interference from the heretofore over-officious operating system.

Hecker knew exactly what game to target as a proof of concept for WinG: DOOM, id Software’s first-person shooter, which had recently risen up from the shareware underground to complete the remaking of a broad swath of gamer culture in the image of id’s fast-paced, ultra-violent aesthetic. If DOOM could be made to run well under WinG, that would lend the system an instant street cred that no other demonstration could possibly have equaled. So, Hecker called up John Carmack, the man behind the DOOM engine. A skeptical Carmack said he didn’t have time to learn the vagaries of WinG and do the port, even assuming it was possible, whereupon Hecker said that he would do it himself if Carmack would just give him the DOOM source — under the terms of a strict confidentiality agreement, of course. Carmack agreed, and Hecker did the job in a single frenzied weekend. (It doubtless helped that Carmack’s DOOM code, which has long since been released to the entire world, is famously clean and readable, and thus eminently portable.)

Hecker brought WinDOOM, as he called it, to the Computer Game Developers Conference in April of 1994, the place where the leading lights of the industry gathered to talk shop among themselves. When he showed them DOOM running at full speed on Windows, just four months after it had become a sensation on MS-DOS, they were blown away. “WinG could usher in a whole new era for computer-based entertainment,” wrote Computer Gaming World breathlessly in their report from the conference. “As a result of this effort, we should expect to see universal installation routines, hardware independence, and an end to the memory-configuration haze that places a minimum technical-expertise barrier over our hobby and keeps out the novice user.”

Microsoft officially released WinG as a Windows 3 add-on in September of 1994, but it never quite lived up to its glowing advance billing. Hecker was a lone-wolf coder, and by some reports at least a decidedly difficult one to work with. Microsoft insiders from the time characterize WinG more as a “hack” than a polished piece of software engineering. Hecker “was able to take a piece of shit called Windows and make games work on it,” says Rick Segal, a Microsoft executive who was then in charge of “multimedia evangelism.” “He strapped a jet engine on a Beechcraft and got the thing in the air.” But when developers started trying to work with it in the real world, “the wings came off first, followed by the rest of the plane.” That’s perhaps overstating the case: WinG combined with Win32S was used to bring a few dozen games to Windows more or less satisfactorily between 1994 and 1997, from strategy games like Colonization to adventure games like Titanic: Adventure Out of Time. WinG was not so much a defective tool as a sharply limited one. While it gave developers a way of getting graphics onto the screen reasonably quickly, it gave them no help with the other pressing problems of sound, joysticks and other controllers, and networking in a game context.

Many of Microsoft’s initiatives during this period were organized by and around their team of “evangelists,” charismatic bright sparks who were given a great deal of freedom and a substantial discretionary budget in the cause of advancing the company’s interests and “fucking the competition,” as it was put by the evangelist for WinG, an unforgettable character named Alex St. John. St. John was a 350-pound grizzly bear of a man who had spent much of his childhood in the wilds of Alaska, and still sported a lumberjack’s beard and a backwoods sartorial sense; in the words of one horrified Microsoft marketing manager, he “looked like a bomb going off.” Shambling onto the stage, the living antithesis of the buttoned-down Microsoft rep that everybody expected, he told his audiences of gamers and game developers that he knew just what they thought of Windows. Then he showed them a clip of a Windows logo being blown away by a shotgun. “The gamers loved it,” says Rick Segal. “They thought they had someone who had their interests at heart.”

St. John soon decided that his constituency deserved something much, much better than WinG. His motivations were at least partly personal. He had come to loathe Chris Hecker, who was intense in a quieter, more penetrating way that didn’t mix well with St. John’s wild-man persona; St. John was therefore looking for a way to freeze Hecker out. But he was also sincere in his belief that WinG just didn’t go far enough toward making Windows a viable platform for hardcore gaming. With Chicago on the horizon, now was the perfect time to change that. He thundered at his bosses that games were a $5 billion market already, and they were just getting started. Windows’s current ineptitude at running them threatened Microsoft’s share in not only that market but the many other consumer-computing spaces that surrounded it. At some point, game developers would say farewell to antiquated MS-DOS. If Microsoft didn’t provide them with a viable alternative, somebody else would.

He rallied two programmers by the names of Craig Eisler and Eric Engstrom to his cause. In attitude and affect, the trio seemed a better fit for the unruly halls of id Software than those of Microsoft. They ran around terrorizing their colleagues with plastic battle axes, and gave their initiative the rather tasteless name of The Manhattan Project — a name their managers found especially inappropriate in light of Japan’s importance in gaming. But they remained unapologetic: “The Manhattan Project changed the world, for good or bad,” shrugged Eisler. “And we really like nuclear explosions.”

As I just noted, St. John’s title of evangelist afforded him a considerable degree of latitude and an equally considerable financial war chest. Taking advantage of the lack of any definitive rejection of their schemes more so than any affirmation of them among the higher-ups, the trio wrote the first lines of code for their new, fresh-from-the-ground-up tools for Windows gaming on December 24, 1994. (The date was characteristic of these driven young men, who barely noticed a family holiday such as Christmas.) St. John was determined to have something to show the industry at the next Computers Game Developers Conference in less than four months.

WinG was also still alive at this point, under the stewardship of the hated Chris Hecker — but not for long. Disney had released a CD-ROM tie-in to The Lion King, the year’s biggest movie, just in time for that Christmas of 1994. It proved a debacle; hundreds of thousands of children unwrapped the box on Christmas morning, pushed the shiny disc eagerly into the family computer… and found out that it just wouldn’t work, no matter how long Mom and Dad fiddled with it. The Internet lit up with desperate parents of sobbing children, and news of the crisis soon reached USA Today and Billboard, who declared Disney’s “Animated Storybook” to be 1994’s Grinch: the game that had ruined Christmas.

Although the software used WinG, that was neither the only nor the worst source of its problems. (That honor goes to its support for 16-bit sound cards only, as stipulated in tiny print on the box, at a time when many or most people still had 8-bit sound cards and the large majority of computers owners had no idea whether they had the one or the other.) Nevertheless, the disaster was laid at the feet of WinG inside the games industry, creating an overwhelming consensus that a far more comprehensive solution was needed if games were ever to move en masse from MS-DOS to Windows. Alex St. John shed no tears: “I was happy to be proven right about WinG’s inadequacy.” The WinG name was hopelessly tainted now, he argued. Chris Hecker was moved to another project, an event which marked the end of active development on WinG. When it came to Windows gaming in the long term, it was now the Manhattan Project or bust.

By the spring of 1995, St. John had managed to assemble a team of about a dozen programmers, mostly contractors with something to prove rather than full-time Microsoft employees. They settled on the label of “Direct” for their suite of libraries, a reference to the way that they would let game programmers get right down to making cool things happen quickly, without having to mess around with all of the usual Windows cruft. DirectDraw would do what WinG had done only better, letting programmers draw on the screen where, how, and when they would; DirectSound would give the same level of flexible control over the sound hardware; DirectInput would provide support for joysticks and the like; and DirectPlay would be in some ways the most forward-looking piece of all, providing a complete set of tools for online multiplayer gaming. The collection as a whole would come to be known as DirectX. St. John, a man not prone to understatement, told Computer Gaming World that “the PC game market has been suppressed for two major reasons: difficulty with installation and configuration, and lack of significant new hardware innovation for games, because developers have had to code so intimately to the metal that it has become a nightmare to introduce new hardware and get it widely adopted. We’re going to bring all the benefits of device independence to games, and none of the penalties that have discouraged them from using APIs.”

It’s understandable if many developers greeted such broad claims with suspicion. But plenty of them became believers in April of 1995, when Alex St. John crashed into the Computer Game Developers Conference like a force of nature. Founded back in 1988 by Chris Crawford, one of gaming’s most prominent philosophers, the CGDC had heretofore been a fairly staid affair, a domain of gray lecture halls and earnest intellectual debates over the pressing issues of the day. “My job was to see DirectX launched successfully,” says St. John. “I concluded that if we set up a session or a suite at the conference itself, no one would come. Microsoft would have to do something so spectacular that it couldn’t be ignored.” So, he rented out the entirety of the nearby Great America amusement park and invited everyone to come out on the day after the conference ended for rides and fun — and, oh, yes, also a presentation of this new thing called DirectX. When he took the stage, the well-lubricated crowd started mocking him with a chant of “DOS! DOS! DOS!” But the chanting ceased when St. John pulled up a Windows port of a console hit called Bubsy, running at 83 frames per second. It became clear then and there that the days of MS-DOS as the primary hardcore-gaming platform were as numbered as those of the old, hype-immune, comfortably collegial CGDC — both thanks to Alex St. John.

St. John and company had never intended to make a version of DirectX for Windows 3; it was earmarked for Chicago, or rather Windows 95, the now-finalized name for Microsoft’s latest consumer operating system. And indeed, most of us old-timer gamers still remember the switch to Windows 95 as the time when we began to give up our MS-DOS installations and have our fun as well as get our work done under Windows. But for all that DirectX couldn’t exist outside of Windows 95, it wasn’t quite of Windows 95. It wasn’t included with the initial version of the operating system that finally shipped, a year behind schedule, in August of 1995; the first official release of DirectX didn’t appear until a month later. “DirectX was built to be parasitic,” says St. John. “It was carried around in games, not the operating system.” What he means is that he arranged to make it possible for game publishers to distribute the libraries free of charge on their installation CDs. When a game was installed, it checked to see whether DirectX was already on the computer, and if so whether the version there was as new as or newer than the one on the CD; if the answer to either of these questions was no, the latest version of DirectX was installed alongside the game it enabled. In an era when Internet connectivity was still spotty and online operating-system updates still a new frontier, this approach doubtless saved game makers many, many thousands of tech-support calls.

Now, though, we should have a look at some of the new features that were an integral part of Windows 95 from the start. Previous versions of Windows were more properly described as operating environments than full-fledged operating systems; one first installed MS-DOS, then installed Windows on top of that, starting it up via the MS-DOS command line. Windows 95, on the other hand, presented itself to the world as a self-contained entity; one could install it to an entirely blank hard drive, and could boot into it without ever seeing a command line. Yet the change really wasn’t as dramatic as it appeared. Unlike Windows NT, Windows 95 still owed much to the past, and was still underpinned by MS-DOS; the elephant balanced on a light pole had become a blue whale perched nimbly up there on one fin. Microsoft had merely become much more thorough in their efforts to hide this fact.

And we really shouldn’t scoff at said efforts. Whatever its underpinnings, Windows 95 did a very credible job of seeming like a seamless experience. Certainly it was by far the most approachable version of Windows ever. It had a new interface that was a vast improvement over the old one, and it offered countless other little quality-of-life enhancements to boot. In fact, it stands out today as nothing less than the most dramatic single evolutionary leap in the entire history of Windows, setting in place a new usage paradigm that has been shifted only incrementally in all the years since. A youngster of today who has been raised on Windows 10 or 11 would doubtless find Windows 95 a bit crude and clunky in appearance, but would be able to get along more or less fine in it without any coaching. This is much less true in relation to Windows 3 and its predecessors. Tellingly, whenever Microsoft has tried to change the Windows 95 interface paradigm too markedly in the decades since, users have complained so loudly that they’ve been forced to reverse course.

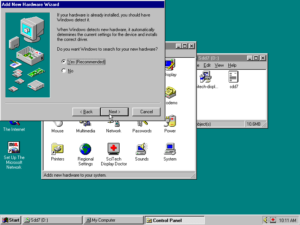

Windows 95 may still have been built on MS-DOS, but 32-bit applications were now the standard, the ability to run 16-bit software relegated to a legacy feature in the name of Microsoft’s all-important backward compatibility. (Microsoft went to truly heroic lengths in the service of the latter, to the extent of special-casing a raft of popular programs: “If you’re running this specific program, do this.” An awful kludge, but needs must…) Another key technical feature, from which tens of millions of people would benefit without ever realizing they were doing so, was “Plug and Play,” which made installing new hardware a mere matter of plugging it in, turning on the computer, and letting the operating system do the rest; no more fiddling about with an alphabet soup of IRQ, DMA, and port settings, trying to hit upon the magic combination that actually worked. Equally importantly, Windows 95 introduced preemptive multitasking in place of the old cooperative model, meaning the operating system would no longer have to depend upon the willingness of individual programs to yield time to others, but could and would hold them to its own standards. At a stroke, all kinds of scenarios — like, say, rendering 3D graphics in the background while doing other work (or play) in the foreground — became much more practical.

A Quick Tour of Windows 95

One of the simplest but most effective ways that Microsoft concealed the still-extant MS-DOS underpinnings of Windows 95 and made it seem like its own, self-contained thing was giving it a graphical boot screen.

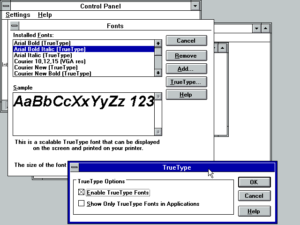

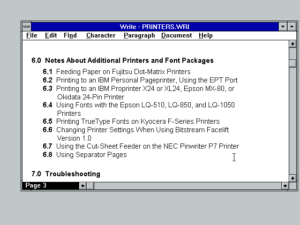

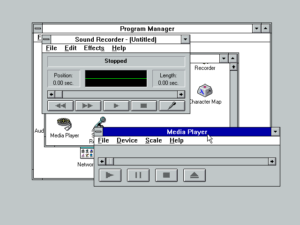

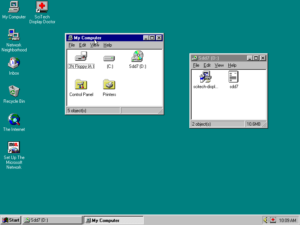

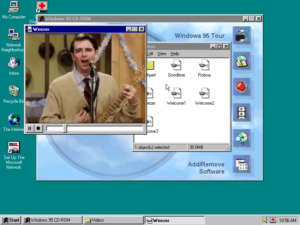

It seems almost silly to exhaustively explicate Windows 95’s interface, given that it’s largely the one we still see in Windows today. Nevertheless, I started a tradition in the earlier articles in this series that I might as well continue. So, note that the old “Program Manager” master window has been replaced by a Mac-like full-screen desktop, with a “Start” Menu of all installed applications at the bottom left, a task bar at the bottom center for switching among running applications, and quick-access icons and the clock at the bottom right. Window-manipulation controls too have taken on the form we still know today, with minimize, maximize, and close buttons all clustered at the top right of each window.

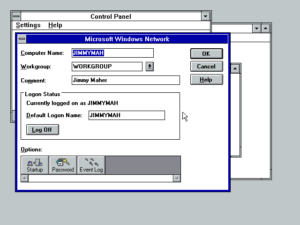

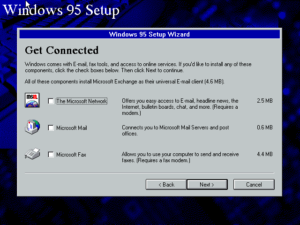

Plug And Play was one of the most welcome additions to Windows 95. Instead of manually fiddling with esoteric settings, you just plugged in your hardware and let Windows do it all for you.

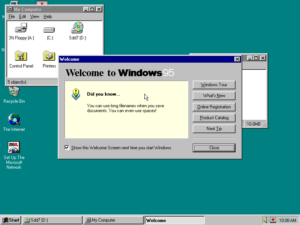

Microsoft bent over backward to make Windows 95 friendly and approachable for the novice. What experienced users found annoying and condescending, new users genuinely appreciated. That said, the hand-holding would only get more belabored in the future, trying the patience of even many non-technical users. (Does anyone remember Clippy?)

In keeping with its role in the zeitgeist, the Windows 95 CD-ROM included a grab bag of random pop-culture non sequiturs, such as a trailer for the movie Rob Roy and a Weezer music video.

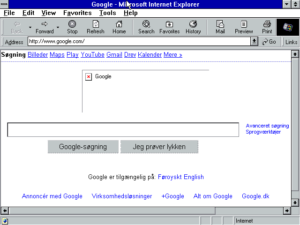

While Windows 95 made a big point of connectivity and did include a built-in TCP/IP stack for getting onto the Internet, it initially sported no Web browser. But that would soon change, with consequences that would reverberate from Redmond, Washington, to Washington, D.C., from Silicon Valley to Brussels.

The most obvious drawback to Windows’s hybrid architecture was its notorious instability; the “Blue Screen of Death” became an all too familiar sight for users. System crashes tended to stem from those places where the new rubbed up against the old — from the point of contact, if you will, between the blue whale’s flipper and the light pole.

Windows 95 stretched the very definition of what should constitute an operating system; it was the first version of Windows on which you could do useful things without installing a single additional application, thanks to built-in tools like WordPad (a word processor more full-featured than many of the commercially available ones of half a decade earlier) and Paint (as the name would imply, a paint program, and a surprisingly good one at that). Some third-party software publishers, suddenly faced with the prospect of their business models going up in smoke, complained voraciously to the press and to the government about this bundling. Nonetheless, the lines between operating systems and applications had been blurred forever.

Indeed, this was in its way the most revolutionary of all aspects of Windows 95, an operating system that otherwise still had one foot rooted firmly in the past. That didn’t much matter to most people because it was a new piece of software engineering second, a flashy new consumer product first. Well before the launch, a respected tech journalist named Andrew Schulman told how “the very name Windows 95 suggests this product will play a leading role” in “the movement from a technology-based into a consumer-product-based industry.”

If a Windows program queries the GetVersion function in Windows 95, it will get back 4.0 as the answer; a DOS program will get back the answer 7.0. But in its marketing, Microsoft has decided to trade in the nerdy major.minor version-numbering scheme (version x.0 had always given the company trouble anyway) for a new product-naming scheme based on that used by automobile manufacturers and vineyards. Windows 95 isn’t foremost a technology or an operating system; it’s a product. It is targeted not at developers or end users but at consumers.

In that spirit, Microsoft hired Brian Eno, a famed composer and producer of artsy rock and ambient music, to provide the now-iconic Windows 95 startup theme. Eno:

The thing from the agency said, “We want a piece of music that is inspiring, universal, blah-blah, da-da-da, optimistic, futuristic, sentimental, emotional,” this whole list of adjectives, and then at the bottom it said, “And it must be 3.25 seconds long.”

I thought this was funny, and an amazing thought to actually try to make a little piece of music. It’s like making a tiny little jewel.

In fact, I made 84 pieces. I got completely into this world of tiny, tiny little pieces of music. Then when I’d finished that and I went back to working with pieces that were like three minutes long, it seemed like oceans of time…

Ironically, Eno created this, his most-heard single composition, on an Apple Macintosh. “I’ve never used a PC in my life,” he said in 2009. “I don’t like them.”

On a more populist musical note, Microsoft elected to make the Rolling Stones tune “Start Me Up” the centerpiece of their unprecedented Windows 95 advertising blitz. By one report, they paid as much as $12 million to license the song, so enamored were they by its synergy with the new Windows 95 “Start” menu, apparently failing to notice in their excitement that the song is actually a feverish plea for sex. “[Mick] Jagger was half kidding” when he named that price, claimed the anonymous source. “But Microsoft was in a big hurry, so they took the deal, unlike anything else in the software industry, where they negotiate to death.” Of course, Microsoft was careful not to include in their commercials the main chorus of “You make a grown man cry.” (Much less the fade-out chorus of “You make a dead man come.”)

Microsoft spent more than a quarter of a billion dollars in all on the Windows 95 launch, making it by a veritable order of magnitude the most lavish to that point in the history of the computer industry. One newspaper said the campaign was “how the Ten Commandments would have been launched, if only God had had Bill Gates’s money.” The goal was to make Windows, as journalist James Wallace put, “the most talked-about consumer product since New Coke” — albeit one that would hopefully enjoy a better final fate. Both goals were achieved. If you had told an ordinary American on the street even five years earlier that a new computer operating system, of all things, would shortly capture the pop-culture zeitgeist so thoroughly, she would doubtless have looked at you like you had three heads. But now it was 1995, and here it was. The Cold War was over, the War on Terror not yet begun, the economy booming, and the wonders of digital technology at the top of just about everyone’s mind; the launch of a new operating system really did seem like just about the most important thing going on in the world at the time.

The big day was to be August 24, 1995. Bill Gates made 29 separate television appearances in the week leading up it. A 500-foot banner was unfurled from the top floor of a Toronto skyscraper, while hundreds of spotlights served to temporarily repaint the Empire State Building in the livery of Windows 95. Even the beloved Doonesbury comic strip was co-opted, turning into a thinly veiled Windows 95 advertisement for a week. Retail stores all over the continent stayed open late on the evening of August 23, so that they could sell the first copies of Windows 95 to eager customers on the stroke of midnight. (“Won’t it be available tomorrow?” asked one baffled journalist to the people standing in line.) There were reports that some impressionable souls got so caught up in the hype that they turned up and bought a copy even though they didn’t own a computer on which to run it.

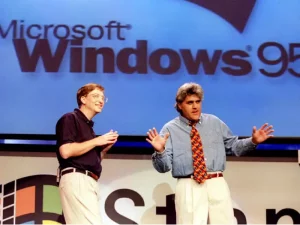

But the excitement’s locus was Microsoft’s Redmond, Washington, campus, which had been turned into a carnival grounds for the occasion, with fifteen tents full of games and displays and even a Ferris wheel to complete the picture. From here the proceedings were telecast live to millions of viewers all over the world. Gates took the stage at 11:00 AM with a surprise sparring partner: comedian Jay Leno, host of The Tonight Show, the country’s most popular late-night talk show. He worked the crowd with his broad everyman humor; this presentation was most definitely not aimed at the nerdy set. His jokes are as fine a time capsule of the mid-1990s as you’ll find. “To give you an idea of how powerful Windows 95 is, it is able to keep track of all O.J.’s alibis at once,” said Leno. Gates wasn’t really so much smarter than the rest of us; Leno had visited his house and found his VCR’s clock still blinking 12:00. As for Windows 95, it was like a good date: “smart, user-friendly, and under $100.” The show ended with Microsoft’s entire senior management team displaying their dubious dance moves up there onstage to the strains of “Start Me Up.” “It was the coolest thing I’ve ever been a part of,” gushed Gates afterward.

Windows 95 sold 1 million copies in its first four days, 30 million copies in its first seven months, 65 million copies in its first sixteen months. (For the record, this last figure was 15 million more copies than the best-selling album of all time, thus cementing the operating system’s place in pop-culture as well as technology history.) By the beginning of 1998, when talk turned to its successor Windows 98, it boasted an active user base three and a half times larger than that of Windows 3.

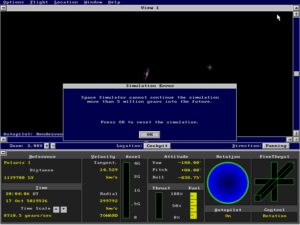

And by that same point in time, the combination of Windows 95 and DirectX had remade the face of gaming. A watershed moment arrived already just one year after the debut of Windows 95, when Microsoft used DirectX to make the first-ever Windows version of their hugely popular Flight Simulator, for almost a decade and a half now the company’s one really successful hardcore gamer’s game. From that moment on, DirectX was an important, even integral part of Microsoft’s corporate strategy. As such, it was slowly taken out of the hands of Alex St. John, Craig Eisler, and Eric Engstrom, whose bro-dude antics, such as hiring a Playboy Playmate to choose from willing male “slaves” at one industry party and allowing the sadomasochistic shock-metal band GWAR to attend another with an eight-foot tall anthropomorphic vagina and penis in tow, had constantly threatened to erupt into scandal if they should ever escape the ghetto of the gaming press and make it into the mainstream. Whatever else one can say about these three alpha-nerds, they changed gaming forever — and changed it for the better, as all but the most hidebound MS-DOS Luddites must agree. By the time Windows 98 hit the scene, vanilla MS-DOS was quite simply dead as a gaming platform; all new computer games for a Microsoft platform were Windows games, coming complete with quick and easy one-click installers that made gaming safe even for those who didn’t know a hard drive from a RAM chip. The DirectX revolution, in other words, had suffered the inevitable fate of all successful revolutions: that of becoming the status quo.

St. John’s inability to play well with others got him fired in 1997, while Eisler and Engstrom grew up and mellowed out a bit and moved into Web technologies at Microsoft. (The Web-oriented software stack they worked on, which never panned out to the extent they had hoped, was known as Chrome; it seems that everything old truly is new again at some point.)

Speaking of the Internet: what did Windows 95 mean for it, and vice versa? I must confess that I’ve been deliberately avoiding that question until now, because it has such a complicated answer. For if there was one tech story that could compete with the Windows 95 launch in 1995, it was surely that of the burgeoning World Wide Web. Just two weeks before Bill Gates enjoyed the coolest day of his life, Netscape Communications held its initial public offering, ending its first day as a publicly traded company worth a cool $2.2 billion in the eyes of stock buyers. Some people were saying even in the midst of all the hype coming out Redmond that Microsoft and Windows 95 were computing’s past, a new era of simple commodity appliances connecting to operating-system-agnostic networks its future. Microsoft’s efforts to challenge this wisdom and compete on this new frontier were just beginning to take shape at the time, but they would soon become the company’s overriding obsession, with well-nigh earthshaking stakes for everyone involved with computers or the Web.

(Sources: the books Renegades of the Empire: How Three Software Warriors Started a Revolution Behind the Walls of Fortress Microsoft by Michael Drummond, Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland, Overdrive: Bill Gates and the Race to Control Cyberspace by James Wallace, The Silicon Boys by David A. Kaplan, Show-stopper!: The Breakneck Race to Create Windows NT and the Next Generation at Microsoft by G. Pascal Zachary, Masters of DOOM: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture by David Kushner, Unauthorized Windows 95: A Developer’s Guide to the Foundations of Windows “Chicago” by Andrew Schulman, Undocumented Windows: A Programmer’s Guide to Reserved Microsoft Windows API Functions by Andrew Schulman, David Maxey, and Matt Pietrek, and Windows Internals: The Implementation of the Windows Operating Environment by Matt Pietrek; Computer Gaming World of August 1994, June 1995, and September 1995; Game Developer of August/September 1995; InfoWorld of March 15 1993; Mac Addict of April 2000; Windows Magazine of April 1996; PC Magazine of November 8 2005. Online sources include an Ars Technica piece on Microsoft’s efforts to keep Windows compatible with earlier software, a Usenet thread about the Lion King CD-ROM debacle which dates from Christmas Day 1994, a Music Network article about Brian Eno’s Windows 95 theme, an SFGate interview with Eno, and Chris Hecker’s overview of WinG for Game Developer. I owe a special thanks to Ken Polsson for his personal-computing chronology, which has been invaluable for keeping track of what happened when and pointing me to sources during the writing of this and other articles. Finally, I owe a lot to Nathan Lineback for the histories, insights, comparisons, and images found at his wonderful online “GUI Gallery.”)