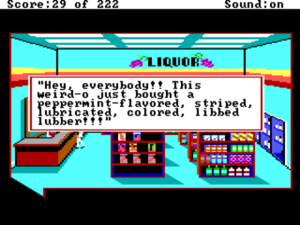

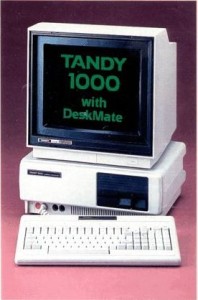

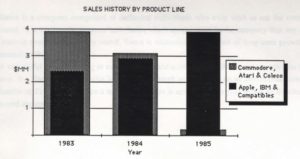

Coming out of Sierra On-Line’s 1984 near-death experience, Ken Williams made a prognostication from which he would never waver: that the real future of home as well as business computing lay with the open, widely cloned hardware architecture of IBM’s computers, running Microsoft’s operating systems. He therefore established and nurtured a close relationship with Radio Shack, whose Tandy 1000 was by far the most consumer-friendly of the mid-1980s clones, and settled down to wait for the winds of the industry as a whole to start to blow his way. But that wait turned into a much longer one than he had ever anticipated. As each new Christmas approached, Ken predicted that this one must be the one where the winds would change, only to witness another holiday season dominated by the cheap and colorful Commodore 64, leaving the MS-DOS machines as relative afterthoughts.

MS-DOS was, mind you, a slowly growing afterthought, one on which Sierra was able to feed surprisingly well. Their unique relationship with Radio Shack in particular made them the envy of other publishers, allowing them as it did to sell their games almost without competition in thousands of stores nationwide. That strategic advantage among others helped Sierra to grow from $4.7 million in gross sales in the fiscal year ending on March 31, 1986, to almost $7 million the following fiscal year.

This sales history from a Sierra prospectus illustrates just how dramatically the company’s customer base changed when Ken Williams made the decision to abandon what he dismissed as the “toy computers” to concentrate on the Apple II and especially the MS-DOS markets.

Still, such incrementalism was hardly a natural fit for Ken Williams’s personality; he was always an entrepreneur after the big gains. It was excruciating waiting for the 8-bit generation of machines to just die already. When IBM debuted their PS/2 line in 1987, Ken, seeing the new machines’ lovely MCGA and VGA graphics and user-friendly mouse support, felt a bit like Noah must have when the first drops of rain finally began to fall. Yes, the machines were ridiculously expensive as propositions for the home, but prior experience said that, given time, their technology would trickle down into more affordable price brackets. If nothing else, the PS/2 line was at long last a start.

Indeed, Ken was so encouraged by the PS/2 line that he decided to pull the trigger on a fraught decision faced by every growing young company: that of whether and when to go public. He decided that October of 1987 would be the right moment, just as Sierra’s lineup of new software for Christmas began to hit the streets. After a frenzy of preparation, all was ready — but then the very week the IPO was to take place opened with Black Monday, the largest single-day stock-market collapse since the mother of all stock-market collapses back in 1929. Sierra quietly abandoned their plans, to little notice from prospective investors who suddenly had much bigger fish to fry.

Sierra had gotten very lucky, and in more ways than one. Had Black Monday been, say, a Black Friday instead, their newly issued shares must inevitably have gotten caught in its undertow, with potentially disastrous results. But even absent those concerns, going public in 1987 was probably jumping the gun just a little, banking on an MS-DOS market that wasn’t quite there yet. This reality was abundantly demonstrated by that Christmas of 1987, the latest to defy Ken’s predictions by voting for the Commodore 64 over MS-DOS — although by this time Commodore’s evergreen was in turn being overshadowed by a new quantity from Japan called the Nintendo Entertainment System.

In fact, the Christmas of 1987 would prove the last of the 64’s strong American holiday seasons. The stars were aligning to make 1988 through 1990 the breakthrough years for both Sierra and the MS-DOS platform to which Ken was so obstinately determined to keep hitching his wagon. In the meantime, the fiscal year ending on March 31, 1988 was nothing to sneeze at in its own right: thanks largely to the new hit Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards and the perennially strong sales of all three extant King’s Quest games, gross sales topped $12 million, enough to satisfy even a greedy entrepreneur like Ken.

That year Sierra broke ground on a new office complex close to their old one in picturesque Oakhurst, California, “at the southern gate of Yosemite National Park,” as their press put it. The new building was made cheaply in comparison to the old one: 40,000 square feet of pre-fab metal that has been variously described as resembling either a warehouse or an aircraft hangar, both inside and out. It would prove a far less pleasant place to work than the lovely redwood building Sierra now abandoned, but that, it seemed, was the price of progress. (Ken claimed to have learned from a survey that his employees actually preferred a cheap building in the name of saving money in order to grow the company in more important ways, but there was considerable skepticism about the veracity of that claim among those selfsame employees.)

To accompany an IPO do-over they had tentatively planned for late in the year, Sierra would have some impressive new gaming technology as well as their impressive — or at least much bigger — new building to put on display. Back in 1986, Ken had made his first trip to Japan, where he’d been entranced by a domestic line of computers from NEC called the PC-9801 series. Although these machines were built around Intel processors and were capable of running MS-DOS, they weren’t hardware-compatible with the IBM standard, a situation that left them much more room for hardware innovation than that allowed to the American clonesters. In particular, the need to display the Japanese Kanji script had pushed their display technology far beyond that of their American counterparts. The top-of-the-line PC-9801VX, with 4096 colors, 1 MB of memory, and a 10 MHz 80286 processor, could rival the Commodore Amiga as a gaming computer. And, best of all, the Japanese accepted the NEC machines in this application; there was a thriving market in games for them. Ken saw in these Japanese machines a window on the future of the American MS-DOS machines, tangible proof of what he’d been saying already for so long about the potential of the IBM/Intel/Microsoft standard to become the dominant architecture in homes as well as businesses. Ken returned from Japan determined that Sierra must push their software forward to meet this coming hardware. Out of this epiphany was born the project to make the Sierra Creative Interpreter (SCI), the successor to the Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI) that had been used to build all of Sierra’s current lineup of adventure games.

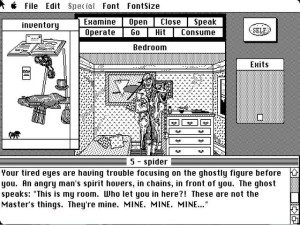

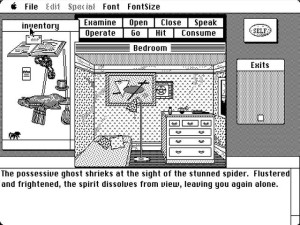

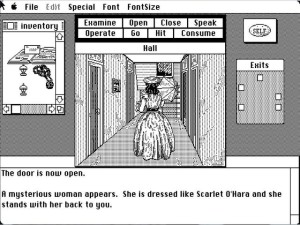

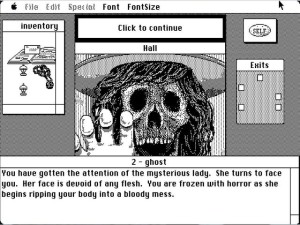

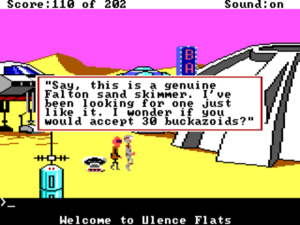

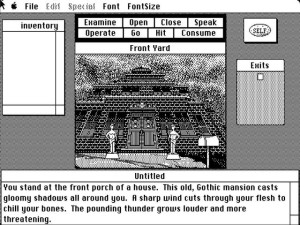

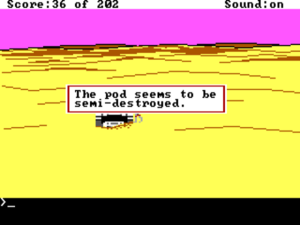

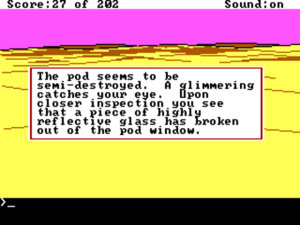

On the surface, the specifications of the first version of SCI hardly overwhelm. The standard display resolution of the engine was doubled, from a rather horrid 160 X 200 to a more reasonable (for the era) 320 X 200, with better support being added for mice and more complex animation possibilities being baked in. Notably, the first version of SCI did not support the impressive but expensive new MCGA and VGA graphics standards; even the technically aggressive Ken Williams had to agree that it was just too soon to be worth the investment.

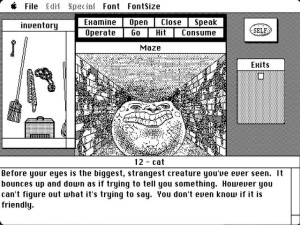

Under the hood, however, the changes were far more extensive than they might appear on the surface. Jeff Stephenson, Sierra’s longtime technology guru, had created AGI on IBM’s dime and IBM’s timetable, in order to implement the original King’s Quest on the ill-fated PCjr. It was a closed and thus a limited system, albeit one that had proved far more flexible and served Sierra far better and longer than anyone had anticipated at the time of its creation. Still, Stephenson envisioned SCI as something very different from its predecessor: a more open-ended, modular system that could grow alongside the hardware it targeted, supporting ever denser and more colorful displays, ever better sound, eventually entirely new technologies like CD-ROM. As indicated by its name, which dropped any specific mention of adventure games, SCI was intended to be a universal engine potentially applicable to many gaming genres. To facilitate such ambitions, Stephenson completely rewrote the language used for programming the engine, going from a simplistically cryptic scripting language to a full-fledged modern programming language reminiscent of C++, incorporating all the latest thinking about object-oriented coding.

Forward-thinking though it was, SCI proved a hard sell to Sierra’s little cadre of game-makers, most of whom lacked the grounding in computer science enjoyed by Jeff Stephenson; they would have been perfectly happy to stick with their simple AGI scripts, thank you very much. But time would show Stephenson to have been correct in designing SCI for the future. The SCI engine, steadily evolving all the while, would last for the remainder of Sierra’s life as an independent company, the technological bedrock for dozens of games to come.

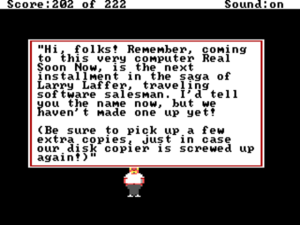

Sierra planned to release their first three SCI-based adventure games in time for Christmas 1988 and that planned-for second-chance IPO: King’s Quest IV, Leisure Suit Larry II, and Police Quest II, with Space Quest III to follow early in 1989. (This lineup says much about Ken Williams’s sequel-obsessed marketing strategy. As an annual report from the period puts it, “Sierra attempts to exploit and extend the effective market life of a successful product by creating sequels to that product and introducing them at planned intervals, thereby stimulating interest in both the sequels and the original product.”) Of this group, King’s Quest IV was always planned as the real showcase for Sierra’s evolving technology, the game for which they would really pull out all the stops — understandably so given that, despite some recent challenges from one (Leisure Suit) Larry Laffer, Roberta Williams’s series of family-friendly fairy-tale adventures remained the most popular games in the Sierra catalog. Indeed, King’s Quest IV marked the beginning of a new, more proactive stance on Sierra’s part when it came to turning the still largely bland beige world of the MS-DOS machines into the new standard for computer gaming. Simply put, with MS-DOS’s consumer uptake threatening to stall again in the wake of the high prices and poor reception of the PS/2 line, Sierra decided to get out and push.

King’s Quest IV‘s most notable shove to the industry’s backside began almost accidentally, with one of Ken’s crazy ideas. He’d decided he’d like to have a real, Hollywood-style soundtrack in this latest King’s Quest, something to emphasize Sierra’s increasingly cinematic approach to adventure gaming in general. Further, he’d love it if said soundtrack could be written by a real Hollywood composer. Never reluctant to liaison with Tinseltown — Sierra had eagerly jumped into relationships with the likes of Jim Henson and Disney during their first heyday years before — he pulled out his old Rolodex and started dialing agents. Most never bothered to return his calls, but at last one of them arranged a meeting with William Goldstein. A former Motown producer, a Grammy-nominated composer for a number of films, and an Emmy-nominated former musical director for the television series Fame, Goldstein also nurtured an interest in electronic music, having worked on several albums of same. He found the idea of writing music for a computer game immediately intriguing. He and Ken agreed that what they wanted for King’s Quest IV was not merely a few themes to loop in the background but a full-fledged musical score, arguably the first such ever to be written for a computer game. As Goldstein explained it to Ken, “the purpose of a score is to evoke emotion, not to be hummed. Sometimes the score consists only of some chord being held and slowly becoming louder in order to create a feeling of tenseness. In creating a score, the instrument(s) it is composed for can be as important as the score itself.”

And therein lay the rub. When Ken demonstrated for him the primitive bleeps and bloops an IBM clone’s speaker was capable of playing, Goldstein pronounced writing a score for that blunt instrument to be equivalent to trying to shoot flies with a shotgun. But then he had an idea. Thanks to his work in other forms of electronic music, Goldstein enjoyed a relationship with the Roland Corporation, a longstanding Japanese maker of synthesizers. Just recently, Roland had released a gadget called the MT-32, a nine-channel synthesizer that plugged into an ordinary IBM-compatible computer. Maybe, Goldstein mused, he could write his score for the MT-32.

At first blush, it seemed a very problematic proposal. The MT-32, which typically went for $550 or more, was hardly an everyday piece of kit; it was aimed at the professional or at least the very serious amateur musician, not at gamers. Yet Ken decided that, faced with a classic chicken-and-egg situation, he needed to do something to move the needle on the deplorable state of IBM-compatible sound hardware. A showpiece game, like King’s Quest IV might become, could show the market what it had been missing and generate demand that might lead to more affordable audio solutions. And so Ken set Goldstein to work on the MT-32.

At the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1988, Sierra gave a series of invitation-only audiences a sneak preview of King’s Quest IV in the form of a nearly ten-minute opening “movie” — people would soon be saying “cut scene” — enhanced by Goldstein’s score. Sierra legend has it that it moved at least one woman to tears. “I feel bad even saying it,” remarks Sierra’s marketing director (and Ken Williams’s little brother) John Williams, “but it was then that we knew we had a winner.”

Such an extreme reaction may be difficult to fathom today; even in King’s Quest IV‘s own time, it’s hard to imagine Amiga owners used to, say, Cinemaware games being quite so awed as this one lady apparently was. But nevertheless, King’s Quest IV and its first real soundtrack score stands as a landmark moment in the evolution of computer games. The game did indeed do much to break the chicken-and-egg conundrum afflicting MS-DOS audio. Only shortly after Roland had released the MT-32, a Canadian company called Ad Lib had released a “Personal Computer Music System” of their own at a price of just $245. It left much to be desired in comparison to the MT-32, but it was certainly worlds better than a simple beeper; Sierra duly added Ad Lib support to King’s Quest IV and all the other SCI games before they shipped. And for Space Quest III, they enlisted the services of another sort of star composer: Bob Siebenberg, drummer of the rock band Supertramp. Thanks in large degree to Sierra’s own determined intervention, in this area at least their chosen platform was becoming steadily more desirable as a game machine.

But King’s Quest IV also advanced the state of the art of adventure gaming in other, less tech-centric ways. As evidenced by its prominent subtitle The Perils of Rosella, its protagonist is female. Hard as it may seem to believe today, when more adventure games than not seem to star women, this fact made King’s Quest IV almost unique in its day; Infocom’s commercially unsuccessful but artistically brilliant interactive romance novel Plundered Hearts is just about the only point of comparison that leaps to mind. Roberta confessed to no small trepidation over the choice at the time of King’s Quest IV‘s release: “I know it will be just fine with the women and girls who play the game, but how it will go over with some of the men, I don’t know.” She also admitted to some ambivalence about her choice in purely practical terms, stemming from differing expectations that are embedded so deeply in our culture that they’re often hard to spot at all until we’re confronted with them.

I have a lot of deaths in my games. My characters always die from falling or being thrown into a cauldron or something. And I always like to have them die in a funny way. It didn’t seem right; I don’t know why. I guess it’s because she’s a girl, and you don’t think a girl should be treated that way. But I got used to that too, until there was one death I had to deal with last week that I was real uncomfortable with. Was it throwing her in the cauldron? I’m not sure, but it was some death that seemed particularly unfeminine, not right.

And girls die differently. I discovered lots of these things, like the way she falls, which has to be different from the way a guy falls. It’s been an experience. And I think that men will find it fun and different because it’s from a different point of view.

One could wish that Roberta’s ambivalence about killing her new female heroine at every possible juncture had led her to consider the wisdom of indulging in all that indiscriminate player-killing at all, but such was not to be. In the end, the most surprising thing about King’s Quest IV‘s female protagonist would be how little remarked upon it was by players. Sounding almost disappointed, Roberta a few months after the game’s release noted that “I personally have not heard much about it.” “I thought it would get a lot of attention,” she went on. “It has gotten some, but nothing really dramatic”; “very few” of the letters she received about the game had anything at all to say about the female heroine.

But then, that non-reaction could of course be taken as a sign of progress in itself. One of the worthiest aspects of Sierra’s determination to turn computer gaming into a truly mainstream form of entertainment was their conviction that doing so must entail reaching far beyond the typical teenage-boy videogame demographic. Doubtless thanks to the relative paucity of hardcore action games and military simulations in their catalog as well as to their having a woman as their star designer, Sierra was always well ahead of most of the rest of their industry when it came to the diversity of their customer base. At a time when female players of other publishers’ games seldom got out of the single digits in percentage terms, Sierra could boast that fully one in four of their players was a woman or a girl; of other 1980s computer-game publishers, only Infocom could boast remotely comparable numbers. In the case of Roberta’s King’s Quest games, the number of female players rose as high as 40 percent, while women and girls wrote more than half of Roberta’s voluminous fan mail.

Sierra’s strides seem all the more remarkable in comparison to the benighted attitudes held by many other publishers. Mediagenic’s Bruce Davis, for instance, busy as usual formulating the modern caricature of the soulless videogame executive, declared vehemently that women and girls were “not a viable market” for games because of “profound” psychological differences that would always lead them to “shun” games. (One wonders what he makes of the modern gaming scene, vast swathes of which are positively dominated by female players.) The role model that Roberta Williams in particular became for many girls interested in games and/or computers should never be overlooked or minimized. Even as of this writing, eighteen years after Roberta published her last adventure game, John Williams tells me how people of a certain age “go crazy” upon learning he’s her brother-in-law, how he still gets at least two requests per week to put people in touch with her for an autograph, how there was an odd surge for a while there of newborn girls named Rosella and Roberta.

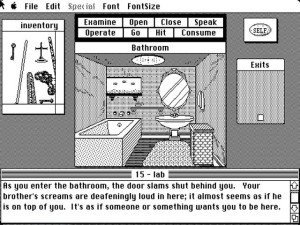

All of this only makes it tougher to reckon with the fact that Roberta’s actual games were so consistently poor in terms of fundamental design. King’s Quest IV is a particular lowlight in her checkered career, boasting some unfair howlers as bad as anything found in her legendarily insoluble Time Zone. At one point, you have to work your way through a horrendous sequence of random-seeming actions to wind up visiting an island, something you can only do one time. On this island is a certain magic bridle you’re going to need later in the game. But, incomprehensibly, the game not only doesn’t ever hint that the bridle may be present on the island, it literally refuses to show it to you even once you arrive there. The only way to find it is to walk around the island step by step, typing “look” again and again while facing in different directions, until you discover those pixels that should by all rights have depicted the bridle but for some reason don’t. Throw in climbing sequences that send you plummeting to your death if you move one pixel too far in the wrong direction, a brutal time limit, and plenty of other potential dead ends almost as heartless as the one just described, and King’s Quest IV becomes as unfair, unfun, frustrating, and downright torturous as any adventure game I’ve ever seen. It’s so bad that, rather than being dismissable as merely a disappointing game, it seems like a fundamentally broken game, thereby raising a question of ethics. Did a player who had just paid $40 for the game not deserve a product that was in fact a soluble adventure game? Even the trade press of King’s Quest IV‘s day, when not glorying over the higher-resolution graphics and especially that incredible soundtrack, had to acknowledge that the actual game underneath it all had some problems. Scorpia, the respected voice of adventure gaming for Computer Gaming World, filled her article on the game with adjectives like “exasperating,” “irritating,” “tedious,” and “boring”, before concluding that “it’s a matter of personal taste” — about as close to an outright pan as most magazine reviewers dared get in those days.

Roberta Williams, an example of that rare species of adventure-game designers who don’t actually play adventure games, likely had little idea just how torturous an experience her games actually were. Taken as a whole, Roberta’s consistent failings as a designer seemingly must stem from that inability to place herself in her player’s shoes, and from her own seeming disinterest in improving upon her previous works in any terms but those of their surface bells and whistles. That said, however, King’s Quest IV‘s unusually extreme failings, even in terms of a Roberta Williams design, quite obviously stemmed from the frenzied circumstances of its creation as well.

I should note before detailing those circumstances that Sierra was finally by the time of King’s Quest IV beginning to change some of the processes that had spawned so many bad adventure games during the company’s earlier years. By 1988, they finally had the beginnings of a real quality-assurance process, dedicating three employees full-time to thrashing away at their games and other software. But, welcome as it was to see testing happening in any form, Sierra’s conception of same focused on the trees rather than the forest. The testers spent their time chasing outright bugs, glitches, and typos, but feedback on more holistic aspects of design wasn’t really part of their brief. In other words, they might spend a great deal of time ensuring that a given sudden death worked correctly without it ever even occurring to them to think about whether that sudden death really needed to be there at all.

In the case of King’s Quest IV, however, even that circumscribed testing process broke down due to the pressure of external events. By the spring of 1988, Roberta had given her design for the game to the team of two artists and two programmers — all recent hires, more fruit of Sierra’s steady expansion — for implementation. Then, with IPO Attempt 2.0 now planned for October of that year and lots of other projects on the boil as well, nobody in management paid King’s Quest IV a whole lot more attention for quite some time, simply assuming that no news from its development team was good news and that it was coming along as expected. Al Lowe, who by the end of that summer had already finished designing and coding his Leisure Suit Larry sequel that was scheduled to ship shortly after King’s Quest IV, picks up the story from here:

King’s Quest IV was going to be the flagship product for the company when we went public. So, Ken and the money guys are busy going around the country, doing their dog-and-pony shows to Wall Street investors, saying, “This is a great company, you’re going to want to buy in, buy lots of stock. We’ve got this great product coming out that’s going to be the hit of the Christmas season.”

Finally, about the end of August, somebody said, “Has anybody looked at that game that’s supposed to be done in a month, that we’re supposed to ship in October? How’s it doing?” They went and looked at it, and the two programmers were lost. They had no clue. They had written a lot of code, but a lot of it was buggy, a lot of it didn’t take proper precautions. One of the big rules of programming is to never allow input at a time you don’t want it, but they had none of that. Everything was wide open. You could break it with a sneeze.

So, they called me and asked if I could come up that weekend — it was Labor Day weekend, Saturday — to look at the game. I did, and said, “Oh, my God, we’re in trouble.” I had a lot of stock options, and was hoping for a successful IPO myself. When I saw this, I said, “We’re in terrible shape. This isn’t going to make it.”

So, we devised a strategy over the weekend to bring every programmer in the company together on Labor Day Monday for a meeting. We said, “All hands are going to work on this title for the next month, and we’re going to finish this game in one month’s time because we’ve got to have it done by the end of September.” Do you remember the phrase from The Godfather, “We’ll go to the mattresses?” That’s what we did; we went to the mattresses. We all moved into the Sierra building. Everybody worked. They brought us food; they did our laundry; they got us hotel rooms. We basically just lived and ate and worked there, and when we needed to sleep we’d go to this hotel nearby. Then we’d get back up and do it again.

I took the lead on the project. I broke the game up into areas, and we assigned a programmer to each. As they finished their code, we had the whole company testing it. We’d distribute bug reports and talk about progress each morning. And by God, by the end of the month we had a game. It wasn’t perfect — it was a little buggy — but at least we had a game we could send out. And when we went public, it was a successful IPO.

Entertaining as this war story is, especially when told by a natural raconteur like Al Lowe, it could hardly result in anything but a bad adventure game. In a desperate flurry like this one, the first thing to fall by the wayside must be any real thoughtfulness about a game’s design or the player’s experience therein.

But despite its many design failings, King’s Quest IV did indeed deliver in spades as the discussion piece and IPO kick-starter it was intended to be. Sierra’s own promotional copy wasn’t shy about slathering on the purple prose in making the game’s case as a technical and aesthetic breakthrough. (In a first and only for Sierra, an AGI version of the game was also made for older systems, but it garnered little press interest and few sales in comparison to the “real” SCI version.)

King’s Quest IV sets a landmark in computer gaming with a new development system that transcends existing standards of computer graphics, sound, and animation. Powerfully dramatic, King’s Quest IV evokes emotion like no other computer game with unique combinations of lifelike animated personalities, beautiful landscapes, and soul-stirring music. Sierra has recreated the universe of King’s Quest to build a world that one moment will pull at your heartstrings, the next moment place terror in your heart.

Leveraging their best promotional asset, Sierra sent Roberta Williams, looking pretty, wholesome, and personable as ever, on a sort of “book tour” to software stores and media outlets across the country, signing autographs for long lines of fans everywhere she went. No one had attempted anything quite like this since the heyday of Trip Hawkins’s electronic artists/rock stars, and never as successfully as this. The proof was in the pudding: King’s Quest IV sold 100,000 copies in its first two weeks and received heaps of press coverage at a time when coverage of computer games in general was all but nonexistent in the Nintendo-obsessed mainstream media. Sales of the game may ultimately have reached as high as 500,000 copies. The IPO went off without a hitch this time on October 6, 1988: 1.4 million shares of common stock were issued at an opening price of $9 per share. Within a year, the stock would be flirting with a price of $20 per share.

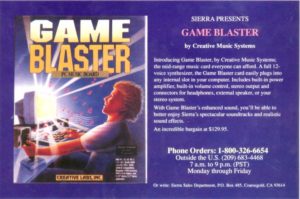

In all their promotional efforts for King’s Quest IV and the rest of that first batch of SCI games, Sierra placed special emphasis on sound, the area where Ken Williams had chosen to try most aggressively to push the hardware forward. The relationship between Sierra and Roland grew so close that Thomas Beckmen, president of the latter company’s American division, joined Sierra’s board. But anyone from any of Roland’s rivals who feared that this relationship would lock them out needn’t have worried. Recognizing that even most purchasers of what they loved to describe as their “premium” products weren’t likely to splash out more than $500 on a high-end Roland synthesizer, Sierra pushed the cheaper Ad Lib alternative equally hard. In 1989, when a Singapore company called Creative Music Systems entered the fray with a cheaper knock-off of the Ad Lib design which they called the Game Blaster, Sierra took it to their bosom as well. (In the end, it was Creative who would be the big winners in the sound-card wars. Their Sound Blaster line, the successor to the Game Blaster, would become the ubiquitous standard for PC gaming through much of the 1990s.) Ken Williams went so far as to compare the latest Sierra games with the first “talkies” to invade the world of silent cinema. Given the sound that users of computers like the Amiga had been enjoying well before Sierra jumped on the bandwagon, this was perhaps a stretch, but it certainly made for good copy.

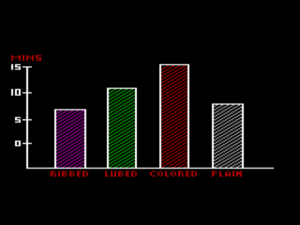

As part of their aggressive push to get sound cards into the machines of their customers, Sierra started selling the products of all three of the biggest rival makers of same directly through their own product catalogs.

Thanks to his own company’s efforts as much as those of anyone, Ken Williams was able to declare at the beginning of 1990 that during the previous year MS-DOS had become “the standard for entertainment software”; the cloudburst this latter-day Noah had been anticipating for so long had come at last. In a down year for the computer-game industry as a whole, which was suffering greatly under the Nintendo onslaught, MS-DOS and the Amiga had been the only platforms not to suffer a decline, with the former’s market share growing from 44 percent to 55 percent. Ken’s prediction that MS-DOS would go from being the majority platform to the absolutely dominant one as 1990 wore on would prove correct.

My guess is that as software publishers plan out their new year’s product schedules, versions of newer titles for machines which are in decline will either be shelved or delayed. Don’t be surprised if companies who traditionally have been strong Apple or Commodore publishers suddenly ship first on MS-DOS. Don’t be surprised if many new titles come out ONLY for MS-DOS next Christmas.

Ken’s emerging vision for Sierra saw his company as “part of the entertainment industry, not the computer industry.” An inevitable corollary to that vision, at least to Ken’s way of seeing things, was a focus on the “media” part of interactive media. In that spirit, he had hired in July of 1989 one Bill Davis, a director of more than 150 animated television commercials, for the newly created position of Sierra’s Creative Director. Davis introduced story-boarding and other new processes redolent of Hollywood, adding another largely welcome layer of systemization to Sierra’s traditionally laissez-faire approach to game development. But, tellingly, he had no experience working with games as games, and nothing much to say about the designs that lay underneath the surface of Sierra’s creations; these remained as hit-and-miss as ever.

The period between 1988 and 1998 or so — the heyday of MS-DOS gaming, before Windows 95/98 and its DirectX gaming layer changed the environment yet again — was one of enormous ferment in computer graphics and sound, when games could commercially thrive on surface sizzle alone. Ken Williams proved more adept at riding this wave than just about anyone else, hewing stolidly as ever to the ten-foot rule he’d formulated during his company’s earliest days: “If someone says WOW when they see the screen from ten feet away, you have them sold.” Sierra, like much of the rest of the industry, took all the wrong lessons from the many bad but pretty games that were so successful during this period, concluding that design could largely be left to take care of itself as long as a game looked exciting.

That Sierra games like King’s Quest IV did manage to be so successful despite their obvious underlying problems of design had much to do with the heady, unjaded times in which they were made — times in which a new piece of “bragware” for showing off one’s new hardware to best effect was worth a substantial price of admission quite apart from its value as a playable game. It also had something to do with Sierra’s masterful fan relations. The company projected an image as friendly and welcoming as their actual games were often unfriendly and obtuse. For instance, in another idea Ken nicked from Hollywood, by 1990 Sierra was offering free daily “studio tours” of their offices, complete with a slick pre-recorded “video welcome” from Roberta Williams herself, to any fan who happened to show up; for many a young fan, a visit to Sierra became the highlight of a family vacation to Yosemite. And of course the success of the King’s Quest games in particular had more than a little to do with the image of Roberta Williams, and the fact that the games were marketed almost as edutainment wares, drawing in a young, patient, and forgiving fan base who may not have fully comprehended that a King’s Quest was, at least theoretically, a game that could be won.

Still, these factors wouldn’t be enough to counter-balance fundamental issues of design forever. Well before the end of the 1990s, both Sierra and the adventure-gaming genre with which they would always be most identified would pay a steep price for too often making design an afterthought. Players, tired of being abused, bored with the lack of innovation in adventure-game design, and no longer quite so easy to wow with audiovisual flash alone, would begin to drift away; this trickle would become a flood which left the adventure genre commercially high and dry.

But all of that was still far in the future as of 1990. For now, Sierra was at the forefront of what they believed to be an emerging new form of mass entertainment, not quite a game, not quite a movie. Gross sales had risen to $21.1 million for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1989, then $29.1 million the following fiscal year. In 1990, they expanded their reach through the acquisition of Dynamix, a six-year-old Oregon-based development house with a rather odd mix of military simulations — after all, Sierra did want men as well as women to continue buying their products — and audio-visually rich if interactively problematic “interactive movies” in their portfolio. Sierra’s years in the MS-DOS wilderness were over; now that same MS-DOS represented the mainstream, soon virtually the only stream of American computer gaming. Some very, very good years lay ahead in commercial terms. And, it must be said, by no means would all of Sierra’s games be failures in terms of design; some talented and motivated designers would soon be using the company’s SCI technology to make interactive magic. So, having given poor King’s Quest IV such a hard time today, next time I’ll be kinder to a couple of other Sierra games that I really don’t like.

Nope… I love them.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of December 1988; Byte of September 1987; Sierra’s newsletters dated Spring 1988, Winter 1988, Spring 1989, Autumn 1989, Spring 1990, Summer 1990; Sierra’s 10th Anniversary promotional brochure; press releases and annual reports found in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Much of this article is also drawn from personal email correspondence with John Williams and Corey Cole. And, last but far from least, Ken Gagne also shared with me the full audio of an interview he conducted with Al Lowe for Juiced.GS magazine. My huge thanks to John, Corey, and Ken!)