Blade Runner has set me thinking about the notion of a “critical consensus.” Why should we have such a thing at all, and why should it change over time?

Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner is an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, about a police officer cum bounty hunter — a “blade runner” in street slang — of a dystopian near-future whose job is to “retire” android “replicants” of humans whose existence on Earth is illegal. The movie had a famously troubled gestation, full of time and budget overruns, disputes between Scott and his investors, and an equally contentious relationship between the director and his leading man, Harrison Ford. When it was finally finished, the first test audiences were decidedly underwhelmed, such that Scott’s backers demanded that the film be recut, with the addition of a slightly hammy expository voice-over and a cheesy happy-ending epilogue which was cobbled together quickly using leftover footage from, of all movies, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.

It didn’t seem to help. The critical consensus on the released version ranged over a continuum from ambivalence to outright hostility. Roger Ebert’s faint praise was typically damning: “I was never really interested in the characters in Blade Runner. I didn’t find them convincing. What impressed me in the film was the special effects, the wonderful use of optical trickery to show me a gigantic imaginary Los Angeles, which in the vision of this movie has been turned into sort of a futuristic Tokyo. It’s a great movie to look at, but a hard one to care about. I didn’t appreciate the predictable story, the standard characters, the cliffhanging clichés… but I do think the special effects make Blade Runner worth going to see.” Pauline Kael was less forgiving of what she saw as a cold, formless, ultimately pointless movie: “If anybody comes around with a test to detect humanoids, maybe Ridley Scott and his associates should hide. With all the smoke in this movie, you feel as if everyone connected with it needs to have his flue cleaned.” Audiences do not always follow the critics’ lead, but in this case they largely did. During its initial theatrical run, Blade Runner fell well short of earning back the $30 million it had cost to make.

Yet remarkably soon after it had disappeared from theaters, its rehabilitation got underway in fannish circles. In 1984, William Gibson published his novel Neuromancer, the urtext of a new “cyberpunk” movement in science fiction that began in printed prose but quickly spiraled out from there into comics, television, and games. Whereas Blade Runner‘s dystopic Los Angeles looked more like Tokyo than any contemporary American city, Gibson’s book actually began in Japan, before moving on to a similarly over-urbanized United States. The two works’ neon-soaked nighttime cityscapes were very much of a piece. The difference was that Gibson added to the equation a computer-enabled escape from reality known as cyberspace, creating a combination that would prove almost irresistibly alluring to science-fiction fans as the computer age around them continued to evolve apace.

Blade Runner‘s rehabilitation spread to the mainstream in 1992, when a “director’s cut” of the film was re-released in theaters, lacking the Captain Obvious voice-over or the tacked-on happy ending but sporting a handful of new scenes that added fresh layers of nuance to the story. Critics — many of them the very same critics who had dismissed the movie a decade earlier — now rushed to praise it as a singular cinematic vision and a science-fiction masterpiece. They found many reasons for its box-office failure on the first go-round, even beyond the infelicitous changes that Ridley Scott had been forced by his backers to make to it. For one thing, it had been unlucky enough to come out just one month after E.T.: The Extraterrestrial, the biggest box-office smash of all time to that point, whose long shadow was as foreboding and unforgiving a place to dwell as any of Blade Runner‘s own urban landscapes. Then, too, the audience was conditioned back then to see Harrison Ford as Han Solo or Indiana Jones — a charming rogue with a heart of gold, not the brooding, morally tormented cop Rick Deckard, who has a penchant for rough sex and a habit of shooting women in the back. In light of all this, surely the critics too could be forgiven for failing to see the film’s genius the first time they were given the chance.

Whether we wish to forgive them or not, I find it fascinating that a single film could generate such polarized reactions only ten years apart in time from people who study the medium for a living. The obvious riposte to my sense of wonder is, of course, that the Blade Runner of 1992 really wasn’t the same film at all as the one that had been seen in 1982. Yet I must confess to considerable skepticism about this as a be-all, end-all explanation. It seems to me that, for all that the voice-over and forced happy ending did the movie as a whole no favors, they were still a long way from destroying the qualities that made Blade Runner distinct.

Some of my skepticism may arise from the fact that I’m just not onboard with the most vaunted aspect of the director’s cut, its subtle but undeniable insinuation that Deckard is himself a replicant with implanted memories, no different from the androids he hunts down and kills. This was not the case in Philip K. Dick’s novel, nor was it the original intention of the film’s scriptwriters. I rather suspect, although I certainly cannot prove it, that even Ridley Scott’s opinion on the subject was more equivocal during the making of the film than it has since become. David Peoples, one of the screenwriters, attributes the genesis of the idea in Scott’s mind to an overly literal reading on his part of a philosophical meditation on free will and the nature of human existence in an early draft of the script. Peoples:

I invented a kind of contemplative voice-over for Deckard. Here, let me read it to you:

“I wondered who designs the ones like me and what choices we really have, and which ones we just think we have. I wondered which of my memories were real and which belonged to someone else. The great Tyrell [the genius inventor and business magnate whose company made the replicants] hadn’t designed me, but whoever had hadn’t done so much better. In my own modest way, I was a combat model.”

Now, what I’d intended with this voice-over was mostly metaphysical. Deckard was supposed to be philosophically questioning himself about what it was that made him so different from Rachael [a replicant with whom he falls in love or lust] and the other replicants. He was supposed to be realizing that, on the human level, they weren’t so different. That Deckard wanted the same things the replicants did. The “maker” he was referring to wasn’t Tyrell. It was supposed to be God. So, basically, Deckard was just musing about what it meant to be human.

But then, Ridley… well, I think Ridley misinterpreted me. Because right about this period of time, he started announcing, “Ah-ha! Deckard’s a replicant! What brilliance!” I was sort of confused by this response, because Ridley kept giving me all this praise and credit for this terrific idea. It wasn’t until many years later, when I happened to be browsing through this draft, that I suddenly realized the metaphysical material I had written could just as easily have been read to imply that Deckard was a replicant, even though it wasn’t what I meant at all. What I had meant was, we all have a maker, and we all have an incept date [a replicant’s equivalent to a date of birth]. We just can’t address them. That’s one of the similarities we had to the replicants. We couldn’t go find Tyrell, but Tyrell was up there somewhere. For all of us.

So, what I had intended as kind of a metaphysical speculation, Ridley had read differently, but now I realize there was nothing wrong with this reading. That confusion was my own fault. I’d written this voice-over so ambiguously that it could indeed have meant exactly what Ridley took it to mean. And that, I think, is how the whole idea of Deckard being a replicant came about.

The problem I have with Deckard being a replicant is that it undercuts the thematic resonance of the story. In the book and the movie, the quality of empathy, or a lack thereof, is described as the one foolproof way to distinguish real from synthetic humans. To establish which is which, blade runners like Deckard use something called the Voight-Kampff test, in which suspects are hooked up to a polygraph-like machine which measures their emotional response to shockingly transgressive statements, starting with stuff like “my briefcase is made out of supple human-baby skin” and getting steadily worse from there. Real humans recoil, intuitively and immediately. Replicants can try to fake the appropriate emotional reaction — might even be programmed to fake it to themselves, such that even they don’t realize what they are — but there is always a split-second delay, which the trained operator can detect.

The central irony of the film is that cops like Deckard are indoctrinated to have absolutely no empathy for the replicants they track down and murder, even as many of the replicants we meet evince every sign of genuinely caring for one another, leading one to suspect that the Voight-Kampff test may not be measuring pure, unadulterated empathy in quite the way everyone seems to think it is. The important transformation that Deckard undergoes, which eventually brings his whole world down around his head, is that of allowing himself to feel the pain and fear of those he hunts. He is a human who rediscovers and re-embraces his own humanity, who finally begins to understand that meting out suffering and death to other feeling creatures is no way to live, no matter how many layers of justification and dogma his actions are couched within.

But in Ridley Scott’s preferred version of the film, the central theme falls apart, to be replaced with psychological horror’s equivalent of a jump scare: “Deckard himself is really a replicant, dude! What a mind fuck, huh?” For this reason, it’s hard for me to see the director’s cut as an holistically better movie than the 1982 cut, which at least leaves some more room for debate about the issue.

This may explain why I’m lukewarm about Blade Runner as a whole, why none of the cuts — and there have been a lot of them by now — quite works for me. As often happens in cases like this one, I find that my own verdict on Blade Runner comes down somewhere between the extremes of then and now. There’s a lot about Roger Ebert’s first hot-take that still rings true to me all these years later. It’s a stunning film in terms of atmosphere and audiovisual composition; I defy anyone to name a movie with a more breathtaking opening shot than the panorama of nighttime Tokyo… er, Los Angeles that opens this one. Yet it’s also a distant and distancing, emotionally displaced film that aspires to a profundity it doesn’t completely earn. I admire many aspects of its craft enormously and would definitely never discourage anyone from seeing it, but I just can’t bring myself to love it as much as so many others do.

These opinions of mine will be worth keeping in mind as we move on now to the 1997 computer-game adaptation of Blade Runner. For, much more so than is the case even with most licensed games, your reaction to this game might to be difficult to separate from your reaction to the movie.

Thanks to the complicated, discordant circumstances of its birth, Blade Runner had an inordinate number of vested interests even by Hollywood standards, such that a holding company known as The Blade Runner Partnership was formed just to administer them. When said company started to shop the property around to game publishers circa 1994, the first question on everyone’s lips was what had taken them so long. The film’s moody, neon-soaked aesthetic if not its name had been seen in games for years by that point, so much so that it had already become something of a cliché. Just among the games I’ve written about on this site, Rise of the Dragon, Syndicate, System Shock, Beneath a Steel Sky, and the Tex Murphy series all spring to mind as owing more than a small debt to the movie. And there are many, many more that I haven’t written about.

Final Fantasy VII is another on the long list of 1990s games that owes more than a little something to Blade Runner. It’s hard to imagine its perpetually dark, polluted, neon-soaked city of Midgar ever coming to exist without the example of Blade Runner’s Los Angeles. Count it as just one more way in which this Japanese game absorbed Western cultural influences and then reflected them back to their point of origin, much as the Beatles once put their own spin on American rock and roll and sold it back to the country of its birth.

Meanwhile the movie itself was still only a cult classic in the 1990s; far more gamers could recognize and enjoy the gritty-cool Blade Runner aesthetic than had actually seen its wellspring. Blade Runner was more of a state of mind than it was a coherent fictional universe in the way of other gaming perennials like Star Trek and Star Wars. Many a publisher therefore concluded that they could have all the Blade Runner they needed without bothering to pay for the name.

Thus the rights holders worked their way down through the hierarchy of publishers, beginning with the prestigious heavy hitters like Electronic Arts and Sierra and continuing into the ranks of the mid-tier imprints, all without landing a deal. Finally, they found an interested would-be partner in the financially troubled Virgin Interactive.

The one shining jewel in Virgin’s otherwise tarnished crown was Westwood Studios, the pioneer of the real-time-strategy genre that was on the verge of becoming one of the two hottest in all of gaming. And one of the founders of Westwood was a fellow named Louis Castle, who listed Blade Runner as his favorite movie of all time. His fandom was such that Westwood probably did more than they really needed to in order to get the deal. Over a single long weekend, the studio’s entire art department pitched in to meticulously recreate the movie’s bravura opening shots of dystopic Los Angeles. It did the trick; the Blade Runner contract was soon given to Virgin and Westwood. It also established, for better or for worse, the project’s modus operandi going forward: a slavish devotion not just to the film’s overall aesthetic but to the granular details of its shots and sets.

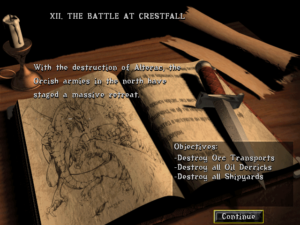

Thanks to the complicated tangle of legal rights surrounding the film, Westwood wasn’t given access to any of its tangible audiovisual assets. Undaunted, they endeavored to recreate almost all of them on the monitor screen for themselves by using pre-rendered 3D backgrounds combined with innovative real-time lighting effects; these were key to depicting the flashing neon and drifting rain and smoke that mark the film. The foreground actors were built from motion-captured human models, then depicted onscreen using voxels, collections of tiny cubes in a 3D space, essentially pixels with an added Z-dimension of depth.

At least half of what you see in the Blade Runner game is lifted straight from the movie, which Westwood pored over literally frame by frame in order to include even the tiniest details, the sorts of things that no ordinary moviegoer would ever notice. The Westwood crew took a trip from their Las Vegas offices to Los Angeles to measure and photograph the locations where the film had been shot, the better to get it all exactly correct. Even the icy, synth-driven soundtrack for the movie was deconstructed, analyzed, and then mimicked in the game, note by ominous note.

The two biggest names associated with the film, Ridley Scott and Harrison Ford, were way too big to bother with a project like this one, but a surprising number of the other actors agreed to voice their parts and to allow themselves to be digitized and motion-captured. Among them were Sean Young, who had played Deckard’s replicant love interest Rachael; Edward James Olmos, who had played his enigmatic pseudo-partner Gaff; and Joe Turkel, who had played Eldon Tyrell, the twisted genius who invented the replicants. Set designers and other behind-the-scenes personnel were consulted as well.

It wasn’t judged practical to clone the movie’s plot in the same way as its sights and sounds, if for no other reason than the absence of Harrison Ford; casting someone new in the role of Deckard would have been, one senses, more variance than Westwood’s dedication to re-creation would have allowed. Instead they came up with a new story that could play out in the seams of the old one, happening concurrently with the events of the film, in many of the same locations and involving many of the same characters. Needless to say, its thematic concerns too would be the same as those of the film — and, yes, its protagonist cop as well would eventually be given reason to doubt his own humanity. His name was McCoy, another jaded gumshoe transplanted from a Raymond Chandler novel into an equally noirish future. But was he a “real” McCoy?

Westwood promised great things in the press while Blade Runner was in development: a truly open-world game taking place in a living, breathing city, full of characters that went about their own lives and pursued their own agendas, whose response to you in the here and now would depend to a large degree on how you had treated them and their acquaintances and enemies in the past. There would be no fiddly puzzles for the sake of them; this game would expect you to think and act like a real detective, not as the typical adventure-game hero with an inventory full of bizarre objects waiting to be put to use in equally bizarre ways. To keep you on your toes and add replay value — the lack of which was always the adventure genre’s Achilles heel as a commercial proposition — the guilty parties in the case would be randomly determined, so that no two playthroughs would ever be the same. And there would be action elements too; you would have to be ready to draw your gun at almost any moment. “There’s actually very little action in the film,” said Castle years later, “but when it happens, it’s violent, explosive, and deadly. I wanted to make a game where the uncertainty of what’s going to happen makes you quiver with anticipation every time you click the mouse.”

As we’ll soon see, most of those promises would be fulfilled only partially, but that didn’t keep Blade Runner from becoming a time-consuming, expensive project by the standards of its era, taking two years to make and costing about $2 million. It was one of the last times that a major, mainstream American studio swung for the fences with an adventure game, a genre that was soon to be relegated to niche status, with budgets and sales expectations to match.

In fact, Blade Runner’s commercial performance was among the reasons that down-scaling took place. Despite a big advertising push on Virgin Interactive’s part, it got lost in the shuffle among The Curse of Monkey Island, Riven, and Zork: Grand Inquisitor, three other swansongs of the AAA adventure game that all competed for a dwindling market share during the same holiday season of 1997. Reviews were mixed, often expressing a feeling I can’t help but share: what was ultimately the point of so slavishly re-creating another work of art if you’re weren’t going to add much of anything of your own to it? “The perennial Blade Runner images are here, including the winking woman in the Coca-Cola billboard and vehicles flying over the flaming smokestacks of the industrial outskirts,” wrote GameSpot. “Unfortunately, most of what’s interesting about the game is exactly what was interesting about the film, and not much was done to extend the concepts or explore them any further.” Computer and Video Games magazine aptly called it “more of a companion to the movie than a game.” Most gamers shrugged and moved on the next title on the shelf; Blade Runner sold just 15,000 copies in the month of its release.[1]Louis Castle has often claimed in later decades that Blade Runner did well commercially, stating at least once that it sold 1 million copies(!). I can’t see how this could possibly have been the case; I’ve learned pretty well over my years of researching these histories what a million-selling game looked like in the 1990s, and can say very confidently that it did not look like this one. Having said that, though, let me also say that I don’t blame him for inflating the figures. It’s not easy to pour your heart and soul into something and not have it do well. So, as the press of real data and events fades into the past, the numbers start to go up. This doesn’t make Castle dishonest so much as it just makes him human.

As the years went by, however, a funny thing happened. Blade Runner never faded completely from the collective gamer consciousness like so many other middling efforts did. It continued to be brought up in various corners of the Internet, became a fixture of an “abandonware” scene whose rise preceded that of back-catalog storefronts like GOG.com, became the subject of retrospectives and think pieces on major gaming sites. Finally, in spite of the complications of its licensing deal, it went up for sale on GOG.com in 2019. Then, in 2022, Night Dive Studios released an “enhanced” edition. It seems safe to say today that many more people have played Westwood’s Blade Runner since the millennium than did so before it. The critical consensus surrounding it has shifted as well. As of this writing, Blade Runner is rated by the users of MobyGames as the 51st best adventure game of all time — a ranking that doesn’t sound so impressive at first, until you realize that it’s slightly ahead of such beloved icons of the genre as LucasArts’s Monkey Island 2 and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis.[2]This chart in general is distorted greatly by the factor of novelty; many or most of the highest-ranking games are very recent ones, rated in the first blush of excitement following their release. I trust that I need not belabor the parallels with the reception history of Ridley Scott’s movie. In this respect as well as so many others, the film and the game seem joined at the hip. And the latter wouldn’t have it any other way.

In all my years of writing these histories, I’m not sure I’ve ever come across a game that combines extremes of derivation and innovation in quite the way of Westwood’s Blade Runner. While there is nary an original idea to be found in the fiction, the gameplay has if anything too many of them.

I’ve complained frequently in the past that most alleged mystery games aren’t what they claim to be at all, that they actually solve the mystery for you while you occupy your time with irrelevant lock-and-key puzzles and the like. Louis Castle and his colleagues at Westwood clearly had the same complaints; there are none of those irrelevancies here. Blade Runner really does let you piece together its clues for yourself. You feel like a real cop — or at least a television one — when you, say, pick out the license plate of a car on security-camera footage, then check the number in the database of the near-future’s equivalent to the Department of Motor Vehicles to get a lead. Even as it’s rewarding, the game is also surprisingly forgiving in its investigative aspects, not an adjective that’s frequently applied to adventures of this period. There are a lot of leads to follow, and you don’t need to notice and run down all of them all to make progress in your investigation. At its best, then, this game makes you feel smart — one of the main reasons a lot of us play games, if we’re being honest.

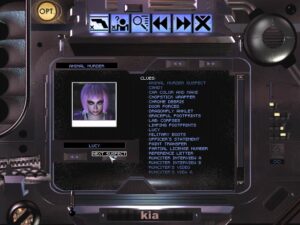

Those problems that do exist here arise not from the developers failing to do enough, but rather from trying to do too much. There’s an impossibly baroque “clues database” that purports to aid you in tying everything together. This experiment in associative, cross-referenced information theory would leave even Ted Nelson scratching his head in befuddlement. Thankfully, it isn’t really necessary to engage with it at all. You can keep the relevant details in your head, or at worst in your trusty real-world notepad, easily enough.

Features like this one seem to be artifacts of that earlier, even more conceptually ambitious incarnation of Blade Runner that was promoted in the press while the game was still being made.[3]Louis Castle’s own testimony contradicts this notion as well. He has stated in various interview that “Blade Runner is as close as I have ever come to realizing a design document verbatim.” I don’t wish to discount his words out of hand, but boy, does this game ever strike me, based on pretty long experience in studying these things, as being full of phantom limbs that never got fully wired into the greater whole. I decided in the end that I had to call it like I see it in this article. As I noted earlier, this was to have been a game that you could play again and again, with the innocent and guilty parties behind the crime you investigated being different each time. It appears that, under the pressure of time, money, and logistics, that concept got boiled down to randomizing which of the other characters are replicants and which are “real” humans, but not changing their roles in the story in response to their status in any but some fairly cosmetic ways. Then, too, the other characters were supposed to have had a great deal of autonomy, but, again, the finished product doesn’t live up to this billing. In practice, what’s left of this aspiration is more of an annoyance than anything else. While the other characters do indeed move around, they do so more like subway trains on a rigid schedule than independent human actors. When the person you need to speak to isn’t where you go to speak to him, all you can do is go away and return later. This leads to tedious rounds of visiting the same locations again and again, hoping someone new will turn up to jog the plot forward. While this may not be all that far removed from the nature of much real police work, it’s more realism than I for one need.

This was also to have been an adventure game that you could reasonably play without relying on saving and restoring, taking your lumps and rolling with the flow. Early on, the game just about lives up to this ideal. At one point, you chase a suspect into a dark alleyway where a homeless guy happens to be rooting through a dumpster. It’s damnably easy in the heat of the moment to shoot the wrong person. If you do so — thus committing a crime that counts as murder, unlike the “retiring” of a replicant — you have the chance to hide the body and continue on your way; life on the mean streets of Los Angeles is a dirty business, regardless of the time period. Even more impressively, you might stumble upon your victim’s body again much later in the game, popping up out of the murk like an apparition from your haunted conscience. If you didn’t kill the hobo, on the other hand, you might meet him again alive.

But sadly, a lot of this sort of thing as well falls away as the game goes on. The second half is rife with learning-by-death moments that would have done the Sierra of the 1980s proud, all people and creatures jumping out of the shadows and killing you without warning. Hope you have a save file handy, says the game. The joke’s on you!

By halfway through, the game has just about exhausted the movie’s iconic set-pieces and is forced to lean more on its own invention, much though this runs against its core conviction that imitation trumps originality. Perhaps that conviction was justified after all: the results aren’t especially inspiring. What we see are mostly generic sewers, combined with characters who wouldn’t play well in the dodgiest sitcom. The pair of bickering conjoined twins — one smart and urbane, the other crude and rude — is particularly cringe-worthy.

Writers and other artists often talk about the need to “kill your darlings”: to cut out those scenes and phrases and bits and bobs that don’t serve the art, that only serve to gratify the vanity of the artist. This game is full of little darlings that should have died well before it saw release. Some of them are flat-out strange. For example, if you like, you can pre-pick a personality for McCoy: Polite, Normal, (don’t call me) Surly, or Erratic. Doing so removes the conversation menu from the interface; walk up to someone and click on her, and McCoy just goes off on his own tangent. I don’t know why anyone would ever choose to do this, unless it be to enjoy the coprolalia of Erratic McCoy, who jumps from Sheriff Andy Taylor to Dirty Harry and back again at a whipsaw pace, leaving everyone on the scene flummoxed.

Even when he’s ostensibly under your complete control, Detective McCoy isn’t the nimblest cowboy at the intellectual rodeo. Much of the back half of the game degenerates into trying to figure out how and when to intervene to keep him from doing something colossally stupid. When a mobster you’ve almost nailed hands him a drink, you’re reduced to begging him silently: Please, please, do not drink it, McCoy! And of course he does so, and of course it’s yet another Game Over. (After watching the poor trusting schmuck screw up this way several times, you might finally figure out that you have about a two-second window of control to make him draw his gun on the other guy — no other action will do — before he scarfs down the spiked cocktail.)

All my other complaints aside, though, for me this game’s worst failing remains its complete disinterest in standing on its own as either a piece of fiction or as an aesthetic statement of any stripe. There’s an embarrassingly mawkish, subservient quality that dogs it even as it’s constantly trying to be all cool and foreboding and all, with all its darkness and its smoke. Its brand of devotion is an aspect of fan culture that I just don’t get.

So, I’m left sitting here contemplating an argument that I don’t think I’ve ever had to make before in the context of game development: that you can actually love something too much to be able to make a good game out of it, that your fandom can blind you as surely as the trees of any forest. This game is doomed, seemingly by design, to play a distant second fiddle to its parent. You can almost hear the chants of “We’re not worthy!” in the background. When you visit Tyrell in his office, you know it can have no real consequences for your story because the resolution of that tycoon’s fate has been reserved for the cinematic story that stars Deckard; ditto your interactions with Rachael and Gaff and others. They exist here at all, one can’t help but sense, only because the developers were so excited at the prospect of having real live Blade Runner actors visit them in their studio that they just couldn’t help themselves. (“We’re not worthy!”) For the player who doesn’t live and breathe the lore of Blade Runner like the developers do, they’re living non sequiturs who have nothing to do with anything else that’s going on.

Even the endings here — there are about half a dozen major branches, not counting the ones where McCoy gets shot or stabbed or roofied midway through the proceedings — are sometimes in-jokes for the fans. One of them is a callback to the much-loathed original ending of the film — a callback that finds a way to be in much worse taste than its inspiration: McCoy can run away with one of his suspects, who happens to be a fourteen-year-old girl who’s already been the victim of adult molestation. Eww!

Even the options menu of this game has an in-joke that only fans will get. If you like, you can activate a “designer cut” here that eliminates all of McCoy’s explanatory voice-overs, a callback to the way that Ridley Scott’s director’s cut did away with the ones in the film. The only problem is that in this medium those voice-overs are essential for you to have any clue whatsoever what’s going on. Oh, well… the Blade Runner fans have been served, which is apparently the important thing.

I want to state clearly here that my objections to this game aren’t abstract objections to writing for licensed worlds or otherwise building upon the creativity of others. It’s possible to do great work in such conditions; the article I published just before this one praised The Curse of Monkey Island to the skies for its wit and whimsy, despite that game making absolutely no effort to bust out of the framework set up by The Secret of Monkey Island. In fact, The Curse of Monkey Island too is bursting at the seams with in-jokes and fan service. But it shows how to do those things right: by weaving them into a broader whole such that they’re a bonus for the people who get them but never distract from the experience of the people who don’t. That game illustrates wonderfully how one can simultaneously delight hardcore fans of a property and welcome newcomers into the fold, how a game can be both a sequel and fully-realized in an Aristotelian sense. I’m afraid that this game is an equally definitive illustration of how to do fan service badly, such that it comes across as simultaneously elitist and creatively bankrupt.

Westwood always prided themselves on their technical excellence, and this is indeed a technically impressive game in many respects. But impressive technology is worth little on its own. If you’re a rabid fan of the movie in the way that I am not, I suppose you might be excited to live inside it here and see all those iconic sets from slightly different angles. If you aren’t, though, it’s hard to know what this game is good for. In its case, I think that the first critical consensus had it just about right.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner by Paul M. Sammon; Computer and Video Games of January 1998; PC Zone of May 1999; Next Generation of July 1997; Computer Gaming World of March 1998; Wall Street Journal of January 21 1998; New Yorker of July 1982; Retro Gamer 142.

Online sources include Ars Technica’s interview with Louis Castle, Game Developer‘s interview with Castle, Edge‘s feature on the making of the game, the original Siskel and Ebert review of the movie, an unsourced but apparently authentic interview with Philip K. Dick, and GameSpot’s vintage Blade Runner review.

Blade Runner is available for digital purchase at GOG.com, in both its original edition that I played for this article and the poorly received enhanced edition. Note that the latter actually includes the original game as well as of this writing, and is often cheaper than buying the original alone…

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Louis Castle has often claimed in later decades that Blade Runner did well commercially, stating at least once that it sold 1 million copies(!). I can’t see how this could possibly have been the case; I’ve learned pretty well over my years of researching these histories what a million-selling game looked like in the 1990s, and can say very confidently that it did not look like this one. Having said that, though, let me also say that I don’t blame him for inflating the figures. It’s not easy to pour your heart and soul into something and not have it do well. So, as the press of real data and events fades into the past, the numbers start to go up. This doesn’t make Castle dishonest so much as it just makes him human. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This chart in general is distorted greatly by the factor of novelty; many or most of the highest-ranking games are very recent ones, rated in the first blush of excitement following their release. |

| ↑3 | Louis Castle’s own testimony contradicts this notion as well. He has stated in various interview that “Blade Runner is as close as I have ever come to realizing a design document verbatim.” I don’t wish to discount his words out of hand, but boy, does this game ever strike me, based on pretty long experience in studying these things, as being full of phantom limbs that never got fully wired into the greater whole. I decided in the end that I had to call it like I see it in this article. |