In the 64 Commodore had their potentially world-beating home computer. Now they needed to sell it. Fortunately, Jack Tramiel still had to hand Kit Spencer, the British mastermind behind the PET’s success in his home country and the VIC-20’s in the United States. The pitchman for the latter campaign, William Shatner, was no longer an option to help sell the 64. His contract had run out just as the new machine was released, and his asking price for another go-round had increased beyond what Tramiel was willing to pay in the wake of his hit television series T.J. Hooker and the movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Spencer decided to forgo a pitchman entirely in favor of a more direct approach that would hammer on the competition while endlessly repeating those two all-important numbers: 64 K and less than $600. He queued up a major advertising blitz in both print and television for the 1982 Christmas season, the second and final time in their history that Commodore would mount such a concentrated, smart promotional effort.

Effective as it was, the campaign had none of the creativity or easy grace of the best advertising from Apple or IBM. The ads simply regurgitated those two critical numbers over and over in a somewhat numbing fashion, while comparing them with the memory size and price of one or more unfortunate competitors. Surprisingly, there was little mention of the unique graphics and sound capabilities that in the long run would define the Commodore 64 as a platform. It almost seems as if Commodore themselves did not entirely understand the capabilities of the chips that Al Charpentier and Bob Yannes had created for them. Still, Spencer showed no fear of punching above his weight. In addition to the 64’s obvious competitors in the low-end market, he happily went after much more expensive, more business-oriented machines like the Apple II and the IBM PC. Indeed, here those two critical numbers, at least when taken without any further context, favored the 64 even more markedly. The computer industry had never before seen advertising this nakedly aggressive, this determined to name names and call out the competition on their (alleged) failings. It would win Commodore few friends inside the industry. But Tramiel didn’t care; the ads were effective, and that was the important thing.

Commodore took their shots at the likes of Apple and IBM, but the real goal had become ownership of the rapidly emerging low-end — read, “home computer” — market. Tramiel’s competition there were the game consoles and the two other computer makers making a serious mass-market play for the same consumers, Atari and Texas Instruments. For the lower end of the low end, Commodore had the VIC-20; for the higher end, the 64.

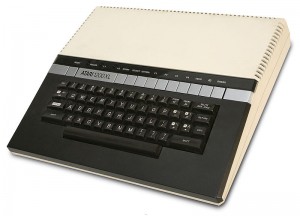

Atari’s big new product for Christmas 1982 was the 5200, a new console based on the same chipset as their computer designs. (Those chips had originally been designed for a successor to the VCS, but rerouted into full-fledged computers when sales of the current VCS just kept increasing. Thus the process finally came full circle, albeit three years later than expected.) The 5200 was something of a stopgap, a rather panicked product from a company whose management had long since lost interest in engineering innovations. It actually marked Atari’s first major new hardware release in three years. Research and development, you see, had shrunk to virtually nil under the stewardship of CEO Ray Kassar, a former titan of the textile industry who held videogames and his customers in something perilously close to contempt. Despite being based on the same hardware, the 5200 was inexplicably incompatible with cartridges for the existing Atari home computers. Those games that were available at launch were underwhelming, and the 5200 was a major disappointment. Only the VCS — now retroactively renamed the 2600 to account for the new 5200 — continued to sell in good quantities, and those were shrinking steadily. Aside from the 2600 and 5200, Atari had only its two three-year-old computers, the chintzy, little-loved 400 and the impressive but also more expensive 800 with only 48 K of memory. With the latter selling for upwards of $600 and both machines halfheartedly (at best) promoted, the big battles of the conflict that the press would soon dub the “Home Computer Wars” would be fought between TI and Commodore. It would be a disappointing Christmas for Atari, and one which foretold bigger problems soon to come.

Put more personally — and very personal it would quickly become — the Home Computer Wars would be fought between Jack Tramiel and the youthful head of TI’s consumer-products division, William J. Turner. The opening salvo was unleashed shortly before the 64’s introduction by, surprisingly, TI rather than Commodore. At that time the TI-99/4A was selling for about $300, the VIC-20 for $240 to $250. In a move they would eventually come to regret, TI suddenly announced a $100 rebate on the TI-99/4A, bringing the final price of the machine to considerably less than that of the inferior VIC-20. With TI having provided him his Pearl Harbor, Jack Tramiel went to war. On the very same day that Turner had opened hostilities, Tramiel slashed the wholesale price of the VIC-20, bringing the typical retail price down into the neighborhood of $175. Despite this move, consumers chose the TI-99/4A by about a three to one margin that Christmas, obviously judging its superior hardware worth an extra $25 and the delayed gratification of waiting for a rebate check. Some fun advertising featuring Bill Cosby didn’t hurt a bit either, while Commodore’s own contract with William Shatner was now history, leaving little advertising presence for the VIC-20 to complement the big push Spencer was making with the 64. TI sold more than half a million computers in just a few months. Round One: TI.

Of course, the 64 did very well as well, although at almost $600 it sold in nowhere near the quantities it eventually would. In those days, computers were sold through two channels. One was the network of dedicated dealers who had helped to build the industry from the beginning, a group that included chains like Computerland and MicroAge as well as plenty of independent shops. A more recent outlet were the so-called mass merchandisers — discounters like K-Mart and Toys ‘R’ Us that lived by stacking ’em deep and selling ’em cheap, with none of the knowledge and support to be found at the dealers. Commodore and TI had been the first to begin selling their computers through mass merchandisers. Here Tramiel and Turner shared the same vision, seeing these low-end computers as consumer electronics rather than tools for hobbyists or businessmen — a marked departure from the attitude of, say, Apple. It really wasn’t possible for a computer to be successful in both distribution models. As soon as it was released to the merchandisers, the game was up for the dealers, as customers would happily come to them to get all of their questions answered, then go make the actual purchase at the big, splashy store around the corner. Commodore’s dealers had had a hard time of it for years, suffering through the limited success of the PET line in the American market only to see Commodore pass its first major sales success there, the VIC-20, to the mass merchandisers. They were understandably desperate to have the 64. Cheap as it was for its capabilities, it still represented much more of an investment than the VIC-20. Surely buyers would want to take advantage of the expertise of a real dealer. Tramiel agreed, or at least claimed to. But then, just as the Christmas season was closing, he suddenly started shipping the 64 to the mass merchandisers as well. Dealers wondering what had happened were left with only the parable of the scorpion and the frog for solace. What could Jack say? It was just his nature. By the following spring the street price of a Commodore 64 had dropped below $400, and it could be found on the shelves of every K-Mart and Toys ‘R’ Us in the country.

With the Commodore 64 joining the VIC-20 in the trenches, Christmas 1982 was looking like only the opening skirmish. 1983 was the year when the Home Computer Wars would peak. This was also the year of the Great Videogame Crash, when the market for Atari 2600 hardware and software went into free fall. In one year’s time Atari went from being the darling of Wall Street to a potentially deadly anchor — hemorrhaging millions of dollars and complete with a disgraced CEO under investigation for insider trading — for a Warner Communications that was suddenly desperate to get rid of it before it pulled the whole corporation down. Just as some had been predicting the previous year, home computers moved in to displace some of the vacuum left by the 2600’s sudden collapse.

In a desperate attempt to field a counterargument to the 64, Atari rushed into production early in 1983 their first new computer since introducing the 400 and 800 more than three years before. Thanks to a bank-switching scheme similar to that of the 64, the Atari 1200XL matched that machine’s 64 K of memory. Unfortunately, it was in almost every other respect a disaster. Atari made the 1200XL a “closed box” design, with none of the expansion possibilities that had made the 800 a favorite of hackers. They used new video hardware that was supposed to be better than the old, but instead yielded a fuzzier display on most monitors and televisions. Worst of all, the changes made to accommodate the extra memory made the new machine incompatible with a whole swathe of software written for the older machines, including many of the games that drove home-computer sales. An apocryphal story has sales of the Atari 800 dramatically increasing in the wake of the 1200XL’s release, as potential buyers who had been sitting on the fence rushed to buy the older machine out of fear it would soon be cancelled and leave them no option but the white elephant that was the 1200XL.

Whatever the truth of such stories, sales for the Atari computer line as a whole continued to lag far behind those of Commodore and TI, and far behind what would be needed to keep Atari a viable concern in this new world order. Huge as Atari (briefly) was, they had no chip-making facilities of their own. Instead, their products were full of MOS chips amongst others. Not only were both their console and computer lines built around the 6502, but MOS manufactured many of the game cartridges for the 2600 and 5200. Thus even when Commodore lost by seeing a potential customer choose an Atari over one of their own machines they still won in the sense that the Atari machine was built using some of their chips — chips for which Atari had to pay them.

Atari would largely be collateral damage in the Home Computer Wars. As I remarked before, however, it was personal between Tramiel and TI. You may remember that almost ten years before these events Commodore had been a thriving maker of calculators and digital watches. TI had entered those markets along with Japanese companies with devices built entirely from their own chips, which allowed them to dramatically undercut Commodore’s prices and very nearly force them out of business. Only the acquisition of MOS Technologies and the PET had saved Commodore. Now Tramiel, who never forgot a slight much less a full-on assault, could smell payback. Thanks to MOS, Commodore were now also able to make for themselves virtually all of the chips found in the VIC-20 and the 64, with the exception only of the memory chips. TI’s recent actions would seem to indicate that they thought they could drive Commodore out of the computer market just as they had driven them out of the watch and calculator markets. But this time, with both companies almost fully vertically integrated, things would be different. Bill Turner’s colossal mistake was to build his promotional campaign for the TI-99/4A entirely around price, failing to note that it was not just much cheaper than the 64 but also much more capable than the VIC-20. As it was, no matter how low Turner went, Tramiel could always go lower, because the VIC-20 was a much simpler, cheaper design to manufacture. If the Home Computer Wars were going to be all about the price tag, Turner was destined to lose.

The TI-99/4A also had another huge weakness, one ironically connected with what TI touted as its biggest strength outside of its price: its reliance on “Solid State Software,” or cartridges. Producing cartridges for sale required vastly more resources than did distributing software on cassettes or floppy disks, and at any rate TI was determined to strangle any nascent independent software market for their machine in favor of cornering this lucrative revenue stream for their own line of cartridges. They closely guarded the secrets of the machine’s design, and threatened any third-party developers who managed to write something for the platform with law suits if they failed to go through TI’s own licensing program. Those who entered said program would be rewarded with a handsome 10 percent of their software’s profits. Thus the TI-99/4A lacked the variety of software — by which I mainly mean games, the guilty pleasure that really drove the home-computer market — that existed for the VIC-20 and, soon, the 64. Although this wasn’t such an obvious concern for ordinary consumers, the TI-99/4A was thus also largely bereft of the do-it-yourself hacker spirit that marked most of the early computing platforms. (Radio Shack was already paying similarly dearly for policies on their TRS-80 line that were nowhere near as draconian as those of TI.) This meant far less innovation, far less interesting stuff to do with the TI-99/4A.

Early in 1983, Commodore slashed the wholesale price of the VIC-20 yet again; soon it was available for $139 at K-Mart. TI’s cuts in response brought the street price of the TI-99/4A down to about $150. But now they found to their horror that the tables were turned. TI now sat at the break-even point, yet Commodore was able to cut the price of the VIC-20 yet further, while also pummeling them from above with the powerful 64, whose price was plunging even more quickly than that of the VIC-20. TI was reduced to using the TI-99/4A as a loss leader. They would just break even on the computer, but would hopefully make their profits on the cartridges they also sold for it. That can be a good strategy in the right situation; for instance, in our own time it’s helped Amazon remake the face of publishing in a matter of a few years with their Kindle e-readers. But it’s dependent on having stuff that people want to buy from you after you sell them the loss leader. TI did not; the software they had to sell was mostly unimpressive in both quality and variety compared to that available for the developer-friendly Commodore machines. And the price of those Commodore machines just kept dropping, putting TI deeper and deeper into a hole as they kept struggling to match. Soon just breaking even on each TI-99/4A was only a beautiful memory.

By September the price of a 64 at a big-box discount store was less than $200, the VIC-20 about $80. Bill Turner had already been let go in disgrace. Now a desperate TI was selling the TI-99/4A at far below their own cost to make them, even as Commodore was continuing to make a modest profit on every unit sold thanks to continuous efforts to reduce production costs. At last, on October 28, 1983, TI announced that it was pulling out of the PC market altogether, having lost a stunning half a billion dollars on the venture to that point in 1983 and gutted their share prices. The TI-99/4A had gone from world beater to fiasco in barely nine months; Turner from visionary to scapegoat in less. As a parting shot, TI dumped the rest of their huge unsold inventory of TI-99/4As onto the market, where at a street price of $50 or less they managed to cause a final bit of chaos for everyone left competing in the space.

But this Kamikaze measure was the worst they could do. Jack Tramiel had his revenge. He had beaten Bill Turner, paid him back with interest for 1982. More importantly, he had beaten his old nemesis TI, delivering an embarrassment and a financial ache from which it would take them a long time to recover. With the battlefield all but cleared, 1983 turned into the Christmas of the Commodore 64. By year’s end sales were ticking merrily past the 2-million-unit mark. Even with all the discounting, North American sales revenue on Commodore’s hardware for 1983 more than doubled from that of 1982. A few non-contenders like the Coleco Adam and second-stringers like Atari’s persistent computer line aside, the Home Computer Wars were over. When their MOS chip-making division and their worldwide sales were taken into account, Commodore was now bigger than Apple, bigger than anyone left standing in the PC market with the exception only of IBM and Radio Shack, both of whose PC divisions accounted for only a small part of their total revenue. The 64 had also surpassed the Apple II as simply the computer to own if you really liked games, while also filling the gap left by the imploded Atari VCS market and, increasingly as the price dropped, the low-end home-computer market previously owned by the VIC-20 and TI-99/4A. Thanks to the Commodore 64, computer games were going big time. Love the platform and its parent company or hate them (and plenty did the latter, not least due to Tramiel’s instinct for the double cross that showed itself in more anecdotes than I can possibly relate on this blog), everybody in entertainment software had to reckon with them. Thanks largely to Commodore and TI’s price war, computer use exploded in the United States between 1982 and 1984. In late 1982, Compute!, a magazine pitched to the ordinary consumer with a low-cost home computer, had a monthly circulation of 100,000. Eighteen months later it was over 500,000. The idea of 500,000 people who not only owned PCs but were serious enough about them to buy a magazine dedicated to the subject would have sounded absurd at the time that the Commodore 64 was launched. And Compute! was just one piece of an exploding ecosystem.

Yet even at this, the supreme pinnacle of Tramiel’s long career in business, there was a whiff of the Pyrrhic in the air as the battlefield cleared. The 64 had barely made it out the door before five of its six principal engineers, the men who had put together such a brilliant little machine on such a shoestring, left Commodore. Among them were both Al Charpentier, designer of its VIC-II graphics chip, and Bob Yannes, designer of its SID sound chip. The problems had begun when Tramiel refused to pay the team the bonuses they had expected upon completing the 64; his justification was that putting the machine together had taken them six months rather than the requested three. They got worse when Tramiel refused to let them start working on a higher-end follow-up to the 64 that would offer 80-column text, a better disk system and a better BASIC, and could directly challenge the likes of the Apple II and IBM PC. And they reached a breaking point when Tramiel decided not to give them pay raises when review time came, even though some of the junior engineers, like Yannes, were barely making a subsistence living.

The five engineers left to start a company of their own. For a first project, they contracted with Atari to produce My First Computer, a product which would, via a membrane keyboard and a BASIC implementation on cartridge, turn the aged VCS into a real, if extremely limited, computer for children to learn with. Tramiel, who wielded lawyers like cudgels and seemed to regard his employees as indentured servants at best, buried the fledgling start-up in lawsuits. By the time they managed to dig themselves out, the VCS was a distant memory. Perhaps for the best in the long run: three of the engineers, including Charpentier and Yannes, formed Ensoniq to pursue Yannes’s love of electronic music. They established a stellar reputation for their synthesizers and samplers and eventually for a line of sound cards for computers which were for years the choice of the discriminating audiophile. Commodore, meanwhile, was left wondering just who was going to craft the follow-up to the 64, just as they had wondered how they would replace Chuck Peddle after Tramiel drove him away in a similar hail of legal action.

Tramiel also inexplicably soured on Kit Spencer, mastermind of the both the VIC-20 and the 64’s public roll-out, although he only sidelined him into all but meaningless bureaucratic roles rather than fire and/or sue him. Commodore’s advertising would never again be remotely as effective as it had been during the Spencer era. And in a move that attracted little notice at the time, Tramiel cut ties with Commodore’s few remaining dealers in late 1983. From now on the company would live or die with the mass merchandisers. For better or worse, Commodore was, at least in North America, now every bit a mass-market consumer-electronics company. The name “Commodore Business Machines” was truly a misnomer now, as the remnants of the business-oriented line that had begun with the original PET were left to languish and die. In later years, when they tried to build a proper support network for a more expensive machine called the Amiga, their actions of 1982 and 1983 would come back to haunt them. Few dealers would have any desire to get in bed with them again.

In January of 1984 things would get even stranger for this company that never could seem to win for long before a sort of institutionalized entropy pulled them sideways again. But we’ll save that story for later. Next time we’ll look at what Apple was doing in the midst of all this chaos.

(I highly recommend Joseph Nocera’s article in the April 1984 Texas Monthly for a look at the Home Computer Wars from the losers’ perspective.)