Apple Computer has remained quite consistent about a number of things throughout all the years of their existence. One of the most striking of these is their complete disinterest in competing on the basis of price. The implicit claim has always been that Apple products are special, made for special people, even as the number of “special people” who buy them have paradoxically in recent years rivaled the numbers of the more plebeian sorts who favor the likes of Microsoft. As such, it’s only just and right that you have to pay a bit of a premium for them. That’s of course a policy every company would have if they could get away with it. The remarkable thing about Apple is that they’ve been able to do just that for several decades now. Partly that success comes down to the sheer dumb luck of coming along at the right moment to be anointed the face of the PC revolution, with an all-American story of entrepreneurship and a charismatic and photogenic young founder that the mainstream media couldn’t help but love. Partly it comes down to a series of products that reflected a real vision for the potentialities of computing as opposed to just offering more MB and MHz than what had come out the previous year. But, perhaps most of all, the world believed Apple was special because Apple believed Apple was special, with a sincere certainty that no PR firm could have faked. At its worst, this quality makes the company and the cult of fanatically loyal users that surrounds it insufferable in their smug insularity. At its best, it lets them change the world in ways that even their perpetual rival Microsoft never quite managed. Bill Gates had a practical instinct for knowing where the computer industry was going and how he could best position Microsoft to ride the wave, but Steve Jobs had a vision for how computer technology could transform life as ordinary people knew it. The conflict between this utopian vision, rooted in Apple’s DNA just as it was in that of Jobs the unrepentant California dreamer himself, and the reality of Apple’s prices that have historically limited its realization to a relatively affluent elite is just one of a number of contradictions and internal conflicts that make Apple such a fascinating study. Some observers perceive Apple as going through something of an identity crisis in this new post-Jobs era, with advertising that isn’t as sharp and products that don’t quite stand out like they used to. Maybe Apple, for thirty years the plucky indie band that belonged to the cool kids and the tastemakers, isn’t sure how to behave now that they’re on a major label and being bought by everyone. Their products are now increasingly regarded as just products, without the aura of specialness that insulated them from direct comparison on the strict basis of price and features for so long.

But that’s now. When the Home Computer Wars got started in earnest in 1982, Apple adopted a policy of, as a contemporaneous Compute! editorial put it, “completely ignoring the low-end market,” positioning themselves as blissfully above such petty concerns as price/feature comparison charts. Even for a company without Apple’s uniquely Teflon reputation that wasn’t necessarily a bad policy to follow. As Texas Instruments and Atari would soon learn, no one had a prayer of beating Jack Tramiel’s vertically-integrated Commodore in a price war. At the same time, though, the new Commodore 64 represented in its 64 K of memory a significant raising of the bar for any everyday, general-purpose PC. In that sense Apple did have to respond, loath as they would have been to publicly admit that the likes of Commodore could have any impact on their strategy. The result, the Apple IIe, was the product not only of the changes wrought to the industry by the Commodore 64 but also of the last several chaotic years inside Apple’s Cupertino, California, headquarters.

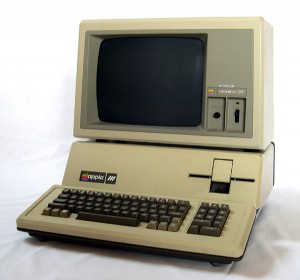

Apple’s superb public image could somewhat belie the fact that through 1982 they had managed to release exactly one really successful computer, the Apple II Plus of 1979. Of the machines prior to the II Plus, the Apple I (1976) had been a mere hobbyist endeavor assembled by hand in Jobs’s garage, and had sold in about the quantities you might expect for such a project; the original Apple II (1977) an impressive proof of concept that was overshadowed by Radio Shack’s cheaper, better distributed TRS-80. It was the 48 K II Plus — mated to Steve Wozniak’s last great feat of minimalist engineering, the Disk II system, and with the PC industry’s first killer app, VisiCalc, in tow — that made Apple. After it… well, there’s quite a tale.

It’s often forgotten that Apple’s early history isn’t just the story of the two kids who started the company in a garage. Right after the two Steves came the two Mikes. Apple’s third and fourth employees, Mike Markkula and Michael Scott, were both older Silicon Valley insiders with money and resumes listing companies like Intel and Fairchild — about as Establishment as you could get. With his role of visionary-in-chief and public spokesman not yet clearly defined, Jobs was the odd man out among the original four, bereft of both Woz’s technical genius and the connections, deep pockets, and business acumen of Markkula and Scott. Tellingly, when Scott issued identification badges for the first time he made Woz, the architect of all of the company’s projects so far and presumed key to their future success, Employee #1, until Jobs’s endless whining convinced him to make him Employee #0 as a compromise. Markkula and Scott managed in remarkably short order to institute a very Establishment bureaucratic structure inside the offices of the supposedly freewheeling Apple. Jobs bounced about the org chart, in Frank Rose’s words “like a feral child” (like the young Bill Gates, the young Steve Jobs was not always big on personal hygiene), leaving chaos in his wake.

Within Apple the II Plus was regarded as the logical end of the road for the Apple II, the ultimate maturation of Woz’s original template. By the time it was released all three of the others were souring on Woz himself. Markkula and Scott found Woz’s lone-wolf style of high-wire engineering to be incompatible with their growing business and its associated bureaucracy, while Jobs resented Woz’s status as the father of the Apple II and desperately wanted to prove himself by creating something of his own, without Woz’s involvement. And so the three came to a tacit agreement to ease Woz aside. Woz himself, whose native guilelessness and naivete are so extreme they can seem almost disingenuous to more cynical souls, simply let it happen without seeming to even realize what was going on. It was decided to divide Apple’s research and development into two projects. One, codenamed Sara, would be a practical attempt to create a logical successor to the Apple II that would be more expensive but also more appealing to businesses and high-end users. The other, codenamed Lisa, would be built around a powerful new processor just released by Motorola, the 68000. As a long-term, blue-sky project, Lisa’s design and ultimate goals would remain quite amorphous for quite some time while most of Apple’s day-to-day effort went into Sara.

The Sara would be designed around the same MOS 6502 CPU as the Apple II, but clocked to 1.8 MHz rather than 1 MHz. A bank-switching scheme would let the machine ship with a full 128 K of memory, with more expansion possible. The graphics would be a dramatic improvement on the Apple II, with higher resolutions and none of the weird color restrictions that could be such a challenge for programmers. The standard text display would now show the 80 columns so critical to word processing and many other business tasks. And replacing the simple ROM-housed BASIC environment of the Apple II would be a more sophisticated operating system booted off of disk. To make sure everyone got the message about this latter, they would even call it the “Sophisticated Operating System,” or, rather unfortunately in light of later developments, SOS. (In one of the more infuriating examples of the endemic cutesiness that has often afflicted Apple, they insisted that “SOS” be pronounced as “Applesauce,” but at least on this occasion most people ended up having none of it.)

It all sounded like a great plan on paper. However, the new group of engineers hired to replace Woz soon had their hands full dealing with Jobs, whose vision for Sara seemed to change by the day. Determined to make Sara “his” machine, he demanded things that were often incompatible with the realities of computer technology circa 1979. The new machine must have a certain external size and shape, leaving the engineers to cram chips into spaces with inadequate ventilation. When they requested an internal fan, Jobs vetoed the idea; he wanted a sleek, elegant, quiet device, not something that sounded like a piece of industrial equipment. In addition to dealing with Jobs, the engineers were also put under enormous pressure to finish Sara, now to be called the Apple III, before Apple’s IPO in December of 1980. Cutting corners all the way, they managed to start shipping the machine just a few weeks before. In retrospect it was a lucky break that they cut it so close, because it meant that reports of what a mess the Apple III was hadn’t filtered up in enough strength or quantity by the time of the IPO to affect it.

Just as the engineers had feared, Apple IIIs started overheating over long use. As they got too hot, chips would expand and come out of their sockets. Apple’s customer-support people were soon reduced to asking angry callers to please pick up their new $6000 wonder-computers and drop them back onto the desk in the hope that this would re-seat the chips. In addition to the overheating, a whole host of other problems cropped up, from shoddy cables to corroding circuit boards. Apple struggled to deal with the problems for months, repairing or replacing tens of thousands of machines. Unfortunately, the replacements were often as unreliable as the originals. Disgusted by the fiasco and by the company culture he felt had led to it (by which he meant largely Markkula and Jobs), Michael Scott quit Apple in July of 1981. With Woz having recognized there was little role left for him at Apple and having started on the first of a series of extended leaves of absence, two of the four original partners were effectively now gone. Far from claiming the Apple III as his equivalent to Woz’s baby the Apple II, Jobs quickly distanced himself from those left struggling to turn this particular sow’s ear into a silk purse. Randy Wigginton, Employee #6, put the situation colorfully: “The Apple III was kind of like a baby conceived during a group orgy, and [later] everybody had this bad headache and there’s this bastard child, and everyone says, ‘It’s not mine.'” Jobs moved on to the Lisa project, which was now really ramping up and becoming Apple’s big priority, not to mention his own great hope for making his mark. When he wore out his welcome there, he moved on yet again, to a new project called Macintosh.

In the end the Apple III remained in production until 1984 despite selling barely 100,000 units in total over that period. Within Apple it came to be regarded as a colossal missed opportunity which could have sewn up the business market for them before IBM entered with their own PC. That strikes me as doubtful. While the Apple III was unquestionably one of the most powerful 6502-based computers ever made on paper and gradually grew to be quite a nice little machine in real life as the remaining dogged engineers gradually solved its various problems, the 8088-based IBM PC was superior in processing power if nothing else, as well as having the IBM logo on its case. The Apple III was certainly damaging to Apple financially, but it could have been worse. Apple’s position as press favorites and the continuing success of the II Plus insulated them surprisingly well; relatively few lost faith in that special Apple magic.

Indeed, as Apple poured money into the Apple III and now into the ever more grandiose Lisa project, the II Plus just kept on selling, long after Apple’s own projections had it fading away. The fact is that the only thing that sustained Apple through this period of flailing about was the II Plus. If Apple’s own projections about its sales had been correct, there wouldn’t be an Apple still around today. Luckily, users simply refused to let it go, and their evangelization of the machine and the many third-party hardware and software makers who supported it kept it selling incredibly strongly even when Apple themselves seemed that they could hardly care less about it. Thanks to Woz’s open design, they didn’t have to; the machine seemed almost infinitely malleable and expandable, an open canvas for others to paint upon. Far from appreciating their loyalty or even simply Apple’s good fortune, Jobs grew more and more frustrated at the Apple II’s refusal to die. He called those parts of the company still dedicated to the line the “dull and boring” divisions, the people who worked in them “Clydesdales” because they were so slow and plodding. He delighted in wandering over to the remnants of the Apple II engineering department (now stuck away in an ugly corner of Apple’s growing campus) to tell everyone how shit all of their products were, seemingly oblivious to the fact that those same products were the only things funding his grander vision of computing.

Dull and boring or not, by 1982 it was becoming obvious that Apple was tempting fate by continuing to leave their only commercially viable computer unimproved. Despite the flexibility of its basic design, some core aspects of the machine were now almost absurdly primitive. For instance, it still had no native support for lower-case letters. And now the much cheaper Commodore 64 was about to be released with a number of features that put the old II Plus to shame. At virtually any moment sales could collapse as users flocked at last to the 64 or something else, taking Apple as a company down with them. Apple may not have been interested in price wars, but it was past time that they reward Apple II users with some sort of sop for their loyalty. An engineer named Walt Brodener turned down a spot on Jobs’s growing Macintosh team to make a next-generation Apple II, out of love of the platform and a desire to sustain the legacy of Woz.

Back in 1980, Brodener and Woz had worked on a project to dramatically reduce the production cost of the II Plus by squeezing the whole design into vastly fewer chips. But then management, caught in the grip of Apple III fever, had cancelled it. The Apple II line, they had reasoned, wouldn’t sell for long enough that the savings would justify the cost of tooling up for a whole new design. Brodener now started again from the old plan he’d put together with Woz, but two more years of ever improving chip-making technology let him take it much further. In the end he and his team reduced the chip count from 120 to an incredible 31, while significantly increasing the computer’s capabilities. Using a bank-switching scheme even more intricate than that of the Commodore 64, they boosted standard memory to 64 K, while also making it possible to further expand the machine to 128 K or (eventually) more. An 80-column text display was now standard, with lower-case letters also making an appearance at long last. Just as the machine entered production, Brodener and his team realized that the changes they had made to implement 80-column text would also allow a new, higher resolution graphics mode with only a few minor changes to the motherboard. Accordingly, all but the first batch of machines shipped with a “double-hi-res” mode. It came with even more caveats and color restrictions than the standard hi-res mode, but it ran at a remarkable 560 X 192. Finally, the new design was also cooler and more reliable. Brodener and team managed all of this while still keeping the new machine 99.9% compatible with software written for the old.

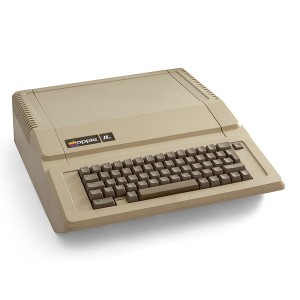

Known as the “Super II” during its development phase, Apple eventually settled on calling the new machine the IIe, as in “Enhanced.” Jobs predictably hated it, finding its big, chunky case with its removable top and row of hacker-friendly expansion slots anathema to his own ideas of computers as elegantly closed designs that were complete in themselves. He sniped at the IIe from its genesis right through its commercial debut and for years afterward. He had plenty of time to do so, because the IIe proved to be a spectacular success right from its release in January of 1983. At last Apple had a true successor to the II Plus, albeit in the form they had least expected and, truth be told, least desired. The Lisa, meanwhile, which shipped at last some six months after the IIe, turned into yet another major disappointment, not recouping a fraction of its huge development cost. Much to Jobs’s chagrin, it seemed that Apple simply couldn’t field a successful product unless it had a “II” on the case.

But what a success the IIe turned out to be, a veritable dream product for any company. Despite its much reduced manufacturing cost, Apple didn’t reduce the new machine’s selling price at all. Why should they, if people were still happy to buy at the old prices? They sold the IIe to distributors at three times their cost to make them, an all but unheard of margin of profit. The machine itself may have reflected little of Jobs’s sensibility, but the price at which Apple sold it was right in line with one of his core business philosophies, as Woz relayed in an anecdote from the earliest days of their friendship:

“Steve had worked in surplus electronics and said if you can buy a part for 30 cents and sell it to this guy at the surplus store for $6, you don’t have to tell him what you paid for it. It’s worth $6 to the guy. And that was his philosophy of running a business.”

There are a couple of ways to look at the outsize disparity between the IIe’s production cost and its selling price. One might see it as borderline unethical, a cynical fleecing of consumers who didn’t know any better and a marked contrast to Commodore’s drive to open up computing for everyone by selling machines that were in some ways inferior but in some ways better for less and less money. On the other hand, all of that seemingly unearned windfall didn’t disappear into thin air. Most of it was rather plowed back into Apple’s ambitious research-and-development projects that finally did change the world. (Not alone, and not to the degree Apple’s own rhetoric tried to advertise, but credit where it’s due.) Jack Tramiel, a man who saw computers as essentially elaborate calculators to be sold on the basis of price and bullet lists of technical specifications, would have been as incapable of articulating such a vision as he would have been of conceiving it in the first place. If nothing else, the IIe shows how good it is to have a cozy relationship with the press and an excellent public image, things Apple mostly enjoyed even in its worst years and Commodore rarely did even in its best. They make many people willing to pay a premium for your stuff and not ask too many questions in the process.

The Apple IIe sold like crazy, a cash cow of staggering proportions. By Christmas of 1983 IIe sales were already approaching the half-million mark. Sales then doubled for 1984, its best year; in that year alone they approached one million units. It would remain in production (with various minor variations) until November of 1993, the most long-lived single product in Apple’s corporate history. During much of that period it continued to largely sustain Apple as they struggled to get Lisa and later, after abandoning that as a lost cause, Macintosh off the ground.

In more immediate terms, the arrival of the Apple IIe also allowed the fruition of a trend in games begun by the Commodore 64. By the end of 1983, with not only the 64 and the IIe but also new Atari models introduced with 64 K of memory, that figure was already becoming a baseline expectation. A jump from 48 K to 64 K may seem a relatively modest one, but it allowed for that much more richness, that much more complexity, and went a long way toward enabling more ambitious concepts that began to emerge as the early 1980s turned into the mid-1980s.

(Unlike the relatively under-served Commodore, there is a wealth of published material on the history of Apple and its internal confusion during this period. Two of the best are West of Eden by Frank Rose and Apple Confidential by Owen Linzmayer. Among other merits, both give an unvarnished picture of what an absolute pain in the ass the young Steve Jobs could be.)