Pool of Radiance is one of the most important CRPGs of all time in terms of both design and the genre’s commercial history. Coming as it did near the end of the line for an 8-bit CRPG tradition that began in earnest with the original Ultima and Wizardry games back in 1981, it’s easy to see it as the culmination of that tradition, blending the ideas and approaches of its predecessors with its own brand new commercial trump card, the Dungeons & Dragons license. The latter was more than enough to move Pool of Radiance and the Gold Box line it spawned into place as the 1B to the Ultima series’s perennial 1A, replacing the Bard’s Tale games, whose own shooting star was now in the descendant. As Wizardry had been replaced by The Bard’s Tale not so long ago, so was The Bard’s Tale now replaced by the Gold Box.

My wife Dorte and I recently played through Pool of Radiance as the first stage in a grander project of trying to take the same party of characters through the entire four-game series that it begins. This article describes what we found therein.

Being the first game in a series that would spawn three direct sequels, Pool of Radiance limits your characters to somewhere between level 6 and 9, depending on class; this is strictly a low- to mid-level adventure, reserving the real power-gaming for its sequels. Still, there’s a big difference between level 1 and level 6, and the thrill of seeing your characters advance and grow in power, so much at the heart of an RPG’s appeal, is the greatest at the lower levels.

The story is appropriate to the characters’ somewhat limited powers. It’s surprisingly modest in scale and scope, at least within the over-the-top context of ludic fantasy in general. Instead of saving the world, you’re “only” out to save a little town called Phlan that’s been largely overrun with monsters in recent years. Like so much about Pool of Radiance, the scenario harks back to the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons experience, to iconic low-level adventures like Gary Gygax’s own The Keep on the Borderlands and the classic British module The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh. In these, as in Pool of Radiance, the stakes for the campaign world are relatively low but the stakes for the players’ party couldn’t be higher. There are, thank God, no “Chosen Ones” or existential universal threats in Pool of Radiance, a welcome distinction that largely holds true throughout the Gold Box line.

In addition to the decidedly modest heights to which characters are allowed to rise in Pool of Radiance specifically, the need to fit the Gold Box games in general into TSR’s existing milieus tended to rein in such excesses. You can’t have every party saving the world when said world needs to be shared by hundreds of adventure modules, source books, computer games, and novels. Those who are invested in the Forgotten Realms as a setting will be able to situate Phlan on a map of the Realms and enjoy the lengthy explication of the region’s history and geography included with the game. Those like me who couldn’t really care less how Phlan fits into the greater Realms don’t have to worry about it.

More interesting to me is the game’s method of telling the more immediate story of your own party of adventurers. As in the contemporaneous Wasteland, much of that story is moved into an accompanying booklet of paragraphs. To my mind, though, Pool of Radiance‘s paragraph book is richer and more interesting than that of Wasteland. In addition to flavor text, you’ll also find maps, diagrams, and illustrations inside the paragraph book to further enrich the experience. And, while I wouldn’t accuse the writing of being precisely good, it is knowing and entertaining in its pulpy cheesiness — and really, how much more can one expect out of such an artificial narrative experience as a traditional monster-bashing CRPG? Dorte and I laughed at the writing a lot, but, hey, it was good-natured laughter; we didn’t go in expecting Shakespeare.

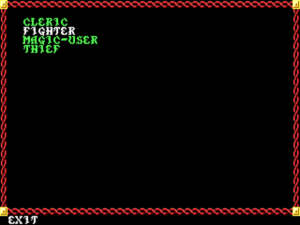

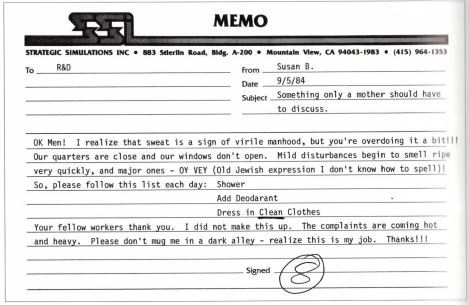

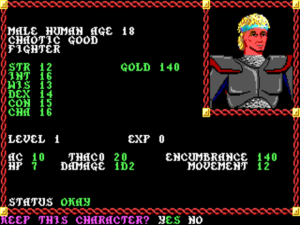

When starting Pool of Radiance, the first order of business — after getting past the irritating code-wheel-based copy protection, that is — must be to create your six-character adventuring party. As was remarked often by disappointed purists back in the day, Pool of Radiance offers nothing close to a full implementation of the byzantine collection of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons hardcovers. You can, for instance, choose among only the four core, archetypal character classes of fighter, cleric, magic user, and thief, combining them with the six races of human, dwarf, elf, gnome, half-elf, and halfling. Personally, I don’t consider such simplifications a negative at all really. Trust me, what’s here is more than (over)complicated enough. More on that later.

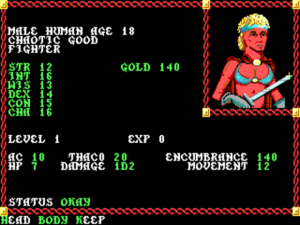

Don’t you love the 1980s permed hair and headband? Makes me want to listen to a little Olivia Newton John.

As usual for games of this tradition, Pool of Radiance lets you re-roll a character’s statistics as many times as you like to get someone you consider viable. Or, if you like, the game lets you bypass all of the virtual dice-rolling and just input starting ability scores of your choice for your characters. Implemented in the service of some ill-defined scheme to let you move your favorite tabletop characters into the computer game, the feature was promptly used by legions of cheaters to make parties full of super characters with the maximum score of 18 in every attribute. But the final joke was on them: Pool of Radiance punishes such players by scaling some of the fights to the overall power of the party, leading to some long, drawn-out combats for the cheaters that those who play fair will breeze through. As we’re beginning to see already, this game does have a way of proving itself more cleverly designed than one initially wants to give it credit for.

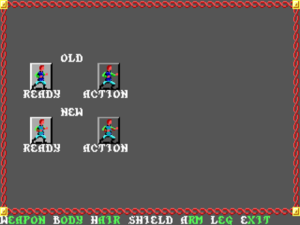

You can combine male heads with female bodies and vice versa when creating a portrait for your character, a feature apparently left in because it amused SSI’s programmers. Combined with the questionable fashion choices, the results can be kind of horrifying.

You can also choose what each character’s “tabletop miniature” will look like, a feature reaching all the way back to Dungeons & Dragons‘s earliest roots in hardcore miniatures wargaming. Unfortunately, it’s hard to see much difference in the icons with these pixelated graphics.

Once you’ve put your party together, you can finally begin the game proper. It opens with your arrival by boat at the last remaining human enclave in the once-thriving village, and a brief guided tour thereof by a representative of the town. The screen layout will be immediately familiar to anyone who’s played a Wizardry or Bard’s Tale game. I would say, however, that just the guide’s introduction alone already contains more text and story content than either of those games.

After the guide is finished, you can start to explore. The opening area is devoid of monsters and completely safe (well, almost; stay out of taverns for a while). It contains all the expected accoutrements of a CRPG home base: shops of various sorts, temples for healing, a training hall for leveling up.

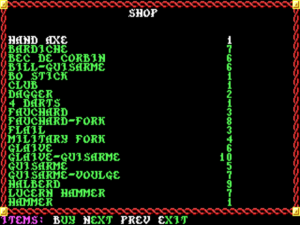

It wouldn’t be Advanced Dungeons & Dragons if the shops didn’t offer a healthy selection of Gary Gygax’s beloved but incomprehensible-to-the-rest-of-us Medieval arms. (“How many kinds of pole arms do you need, Gary?” asked Dave Arneson. “It’s a stick with a pointy thing on the end of it!”) Players of course always ignore all the Gallic gibberish and just pick out a trusty long sword, axe, or mace. None of the weird stuff is used by any of the creatures you fight, nor is it found in any of their treasure hoards, triggering a sneaking suspicion that the designers of Pool of Radiance had no more idea what any of this is than the rest of us do.

Another nod to the classic tabletop experience is the table of “tavern tales” found in the paragraph book, just like the ones found in Keep on the Borderlands and all those other early Dungeons & Dragons adventure modules. (How many modules start with the party meeting in a tavern and overhearing rumors about that nearby castle/dungeon/graveyard/monastery?)

Your goals in Pool of Radiance are delivered in the form of commissions found at the city clerk’s office. Several are usually available at any one time, giving the game a welcome non-linearity. As you carry out commissions, you return to the clerk to check them off your to-do list and to receive rewards in the form of experience and money. The whole process is immensely satisfying. As you build up your party, you venture further and further afield, claiming back more and more of Phlan from the monsters. This modest exercise in urban renewal feels far more rewarding than the elaborate save-the-world plots found in most CRPGs.

Another thing that happens as you complete commissions is that you gain a better and better overview of Phlan and its environs as a whole, learning how it all fits together. As usual in such old-school CRPGs as this one, each area is a fixed size, of 16 by 16 squares in this case. Yet SSI made the effort to make them fit together in logical, even intriguing ways to build a larger environment. If you can manage to get yourself in the right frame of mind, mapping really does become one of Pool of Radiance‘s pleasures. Dorte, a spatial-puzzle-loving fan of Carcassonne and Blokus in all the ways I am not, is the cartographer when we play Gold Box games. (I’m the driver; she wants nothing to do with that quirky interface.) I caught her from time to time when we weren’t playing redrawing and repositioning and even taping together her level maps to create a grand plan of Phlan: “This is fun!”

Making mapping far more fun in Pool of Radiance is the game’s complete disinterest in all of the nonsense that’s usually associated with it. There are no spinners or teleports or other artificial time-extenders and frustration-inducers. Unlike The Bard’s Tale, Pool of Radiance has enough real content that it doesn’t need that stuff. Indeed, the designers bent over backward to make mapping as painless as possible. Your grid location on the current map is usually shown right there onscreen, as is the direction you’re currently facing; note the “5, 5” and the “E” respectively on the screenshot above. There’s even an overhead auto-map of sorts. It’s not quite ideal — doors don’t show up on it, nor for that matter anything else other than walls and corridors — but, hey, it shows that they were trying. It’s all part of a thoroughgoing theme of Pool of Radiance, that of duplicating most of the gameplay of its predecessors in the broadest strokes, but doing it all just a little bit better, a little bit smarter, and most of all with a little bit more mercy on you, the long-suffering player.

For instance, consider the case of the wandering monster. In Wizardry or The Bard’s Tale, entering a new area always brings a little thrill of excitement as you get to see what types of new critters now come after you. That excitement dissipates, however, as the same handful of monsters just keep coming at you. Pretty soon you just wish you could move around and finish drawing your map without being attacked by endless hordes of the same old same old.

Pool of Radiance fixes this problem, simply and ingeniously and without requiring much technical innovation at all. When you enter a new area, you do indeed find it populated with the expected horde of wandering monsters. Once you’ve fought and won a certain number of combats, though, they simply stop coming. Your overarching goal being to clear the monsters out of Phlan, this makes a great deal of thematic sense for this particular game. But more importantly, it makes a lot of sense as good game design in general. Combined with lots of interesting fixed encounters, far more than the one or two typical of a Wizardry or Bard’s Tale dungeon level, it keeps the game from ever descending into a dull grindfest. Just when you’re starting to get tired of a stream of samey encounters, they stop. I can’t overemphasize what a difference this one simple act of mercy makes for my own enjoyment of Pool of Radiance. Suddenly an entire genre of gaming that used to bore me becomes a pleasure. The older I get and the more loath I become to waste my time on anything if I can help it, the more my first rule of game design becomes a match for my first rule of writing: don’t be boring.

Pool of Radiance‘s adherence to that maxim extends to the times when you do have to fight; combat in this game is a magnificent experience. I think most fans of Pool of Radiance and the other Gold Box games would agree with me that their beating heart is the best combat engine yet devised for a CRPG at the time of their release. Indeed, some would argue that these games still haven’t been bettered in this respect if your definition of good CRPG combat is a cerebral, tactical, turn-based affair. (Granted, such a thing is not particularly in step with mainstream tastes these days.) There’s a welcome logic at play here that’s painfully absent from virtually all of the Gold Box series’s rivals. Because combat is what you spend the vast majority of your time doing in these old CRPGs, the designers of this one decided to take the time to make it really, really great.

And, like so much about the Gold Box games, the focus on intricate combat is also a perfect fit for the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons license. Many have accused that game of not being a role-playing game at all, rather a 1:1-scale wargame focusing on combat almost to the exclusion of all else. Whether you consider that description to be a criticism or not — one suspects that that’s exactly what many if not most players really wanted from the game anyway — Pool of Radiance does its inspiration proud. Just as combat is the essence of Dungeons & Dragons, combat is the essence of the Gold Box games.

Take, for instance, the inevitable mass-damage Fireball spell, a staple of just about every fantasy CRPG ever made. When your magic user gains access to Fireball in the latter stages of Pool of Radiance, it’s a big moment. Yet it’s still not something you can use quite as mindlessly as you can in other games. This Fireball spell has a set area of effect, and doesn’t discriminate between friend and foe. Therefore you need to place it very, very carefully to avoid nuking your own party. You also have to reckon with range, line of sight, and even the spell’s casting time when doing so; if your magic user gets hit while she’s busy casting a spell, she loses it. None of which is to say that a spell like Fireball isn’t wonderful. Quite the opposite: it’s all the more satisfying when a well-placed explosion takes out an entire rank of orcs. And then there’s Lightning Bolt, another spell you’ll acquire at about the same time as Fireball that’s even more tricky to set up just perfectly, and even more satisfying when it works. There are many layers to the onion of Gold Box combat, and they only multiply as you climb the ranks and build more powerful characters — and of course find yourself fighting more powerful monsters as you do so, often with special attacks of their own to go with unique immunities and vulnerabilities that demand you adjust your tactics constantly.

In fact, one might argue that when it comes to combat Pool of Radiance actually betters the typical tabletop experience as most real players knew it. Gary Gygax’s elaborate rules for combat presumed a lot of knowledge about where all of the various combatants were standing in relation to one another and the environment, but it was never entirely clear how to plot and keep track of all that without infinite time to draw up floor plans or construct scale models of the environment. But the computerized Dungeons & Dragons has no problem coming up with such plans on the fly, presenting each battle using wargamey “miniatures” that would have warmed Gygax’s heart and keeping track of all of the other complications that usually led to fudging, simplifying, and house-ruling the tabletop game. One might say that all those fiddly rules were just waiting all along for SSI to come along and make them actually playable. Gold Box combat rules. I can’t emphasize that enough. It’s so wonderful that I’m willing to forgive a lot about the rest of the game that surrounds it.

And that’s good because, almost paradoxically given how progressive Pool of Radiance is in many ways, there really is quite a lot to forgive here. The game’s biggest strength is also its biggest weakness: almost every one of its numerous frustrating, infuriating qualities stems from an overzealous faithfulness to the fiddly rules of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.

To begin with, there’s the racial level limits, which arbitrarily cap the maximum advancement in all classes except thief for all races except humans. The level limits are something of a hidden poison pill whose effect won’t hit you until you import your old party with all of their hard-won experience into Pool of Radiance‘s sequel. It comes as a hard blow indeed when you realize that some of your stalwarts are going to be untenable because they can’t keep pace with the escalating power of the opponents they will be facing in that game and the ones that follow. All you can do is cast your old non-human characters aside and roll up new, human characters to replace them. This is terrible game design, all courtesy of our old friend Gary Gygax. Here’s his justification:

The character races in the AD&D system were selected with care. They give variety of approach, but any player selecting a non-human (part- or demi-human) character does not have any real advantage. True, some of those racial types give short-term advantages to the players who choose them, but in the long run, these same characters are at an equal disadvantage when compared to human characters with the same number of experience points. This was, in fact, designed into the game. The variety of approach makes role selection more interesting. Players must weigh advantages and disadvantages carefully before opting for character race, human or otherwise. It is in vogue in some campaigns to remove restrictions on demi-humans — or at least relax them somewhat. While this might make the DM popular for a time with those participants with dwarven fighters of high level, or elven wizards of vast power, it will eventually consign the campaign as a whole to one in which the only races will be non-human. Dwarves, elves, et al will have all the advantages and no real disadvantages, so the majority of players will select those races, and humankind will disappear from the realm of player character types. This bears upon the various hybrid racial types, as well.

Like so many of Gygax’s justifications, this one is patent nonsense. (I do, however, treasure the smirking reference to what’s “in vogue” — classic Gygax through and through.) The way to ensure that humans stay viable and desirable, if that’s a design goal, isn’t to cripple all of the other races so badly that they become pointless, but to offer some similar off-setting advantage to humans. Humans in TSR’s own Star Frontiers tabletop RPG, for instance, get to add some bonus points to the ability scores of their players’ choice, justified with a paean to humanity’s sheer jack-of-all-trades adaptability in contrast to the more specialized powers of the other races.

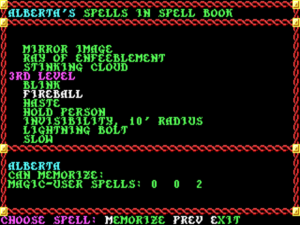

We also have Gygax to thank for Pool of Radiance‘s convoluted method of handling spells. Unlike virtually every other CRPG but like tabletop Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, a cleric or magic user’s list of spells in this game isn’t treated as a handy universal repository from which she can fire off the spell of her choice at will (as long, of course, as she still has the mana to do so). No, in the Gold Box games you have to memorize ahead of time the precise spells you think you will actually want to use on your next expedition. Because you usually don’t know precisely what kind of monsters you’ll be fighting in the course of said expedition, you’re continually being caught out with the wrong selection of spells. Run into a pack of disease-causing undead without having memorized Cure Disease? Too bad; reload back at camp and try a different spell arsenal. Run into the rare locked door that your fighters can’t bash in, and you don’t have Knock memorized? Take the long walk back to a safe area to rest and memorize it. There’s no strategy to any of this, just rote trial and error. The system is actively damaging to the pleasure induced by that magnificent combat engine. Because so many of the more specialized spells are useful only in specific situations, you end up treating every encounter as a nail and always having lots of Fireball hammers memorized to bash it with. How much better would it be to feel the thrill of satisfaction that comes with a well-timed Animate Dead, Blink, or Invisibility 10′ Radius?

One can only be thankful that SSI didn’t see fit to implement the tabletop rules’ requirement that characters collect a bunch of “material components” to cast most spells. (Interestingly, a similar system did show up in Ultima, with its system of “reagents.”) Presumably it was just too much to fit into a program that needed to run on a Commodore 64 — and thank God for that.

The most initially baffling of all the design choices in Pool of Radiance — baffling, that is, if you aren’t familiar with the tabletop game — is its handling of money. First of all, the game insists on dividing your funds into different types of coins — platinum, gold, electrum, ad nauseam — and keeping rigorous track of exactly how many of each coin your characters carry. It would be like a game with a contemporary setting telling you that you have 2 five-dollar bills, 2 one-dollar bills, 3 quarters, 1 dime, 1 nickel, and 7 pennies instead of just telling you you have $12.97. All because, once again, that’s how Gygax says you should do it. The Gold Box games are quite possibly the only CRPGs in history where your quest can hinge on whether you have the correct change for something. How’s that for heroic fantasy?

And then there’s just so much money. Phlan and its environs are drowning in wealth. Because the weight of all of those individualized coins is meticulously tracked, you can’t carry it all; never have Dorte and I wished more for a bank than during our time in Phlan. Within a few hours, you’ll be leaving mountains of coins behind after encounters as a matter of course, dropping coins in the street, leaving shopkeepers 1000-platinum-piece tips after spending 10 gold pieces on a few arrows. Forget trying to reclaim the village from the monsters; there’s enough money in Phlan to buy each and every citizen a mansion in whatever is the Forgotten Realms’s equivalent of Beverly Hills. What on earth is going on here? Why would anyone design a game this way?

Well, what’s going on here is a vicious conflict between the needs of Pool of Radiance the computer game and the tabletop Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules. Those rules are as persnickety about experience points as they are about most things, allowing Dungeon Masters to award them for exactly two things: killing monsters and finding treasure. A tabletop Dungeons & Dragons campaign is — or was meant to be — a slow-paced affair, with characters spending many months at each level. In the Dungeon Master’s Guide and elsewhere, Dungeon Masters are continually cautioned not to let their campaigns devolve into “Monty Haul” affairs where magic items and experience points are passed out like candy. Yet a CRPG like Pool of Radiance is in fact by necessity a Monty Haul affair. People don’t want to spend months waiting for their computer characters to level up. People want to see them move through the ranks in relatively short order, want a more concentrated dose of the RPG experience. So, SSI needed to increase the pace. The obvious way to do that was to hand out more experience more quickly. Yet they were bound to the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules that coupled experience awards strictly to monsters killed and hoards looted. And now we begin to understand the broken economy: all that money is flying around strictly as a way of passing experience to characters without violating the letter of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules; the spirit of the rules is, of course, another matter entirely.

The natural next question is to ask why SSI felt themselves bound so strictly to the tabletop rules, even when it proved so damaging to the finished product. The obvious supposition is that TSR, fiercely protective of Dungeons & Dragons as they always were both before and after the era of Gary Gygax, told them they were so bound. The contemporary adventure-game reviewer and columnist Shay Addams, who may or may not have been reporting information gleaned from contacts at SSI, claimed that “TSR insisted that SSI stick by the original rules, and they had final say on the finished product.” While the latter assertion is certainly true, the idea of an overly pedantic, nitpicky TSR is somewhat cast into doubt by the fact that people who were associated with the Gold Box project at SSI don’t tend to describe the relationship in those terms today. Instead we hear always of a genuinely collaborative relationship filled with lots of give and take, a relationship so warm that it spawned cross-company friendships that persisted in some cases long after both companies ceased to exist. Further, one has to presume that the folks SSI was working with at TSR were all too aware themselves of what a confusing muddle Advanced Dungeons & Dragons could be, for they were hard at work on a second edition of the rules that was meant to untangle some of their Gygaxian knots at the very time that SSI was developing Pool of Radiance.

But, whether the compulsion to so literally translate so many rules from tabletop to desktop arose from within TSR or SSI, Addams is right about its effect: “That restriction must have been creatively inhibiting, for it means ignoring much of what game designers have learned about writing RPGs designed to be played on a computer — which are decidedly different from face-to-face games.” Advanced Dungeons & Dragons proved a double-edged sword for Pool of Radiance, the source of much of what is good in it and most of what is bad. I’m not sure that I’ve ever reviewed another game that so freely mixes really good ideas with really bad ones. Too often Pool of Radiance feels like playing tabletop Dungeons & Dragons with the most humorlessly pedantic Dungeon Master ever.

On balance, though, the good outweighs the bad — which I must say kind of surprises me, given that there’s so very much I love to complain about in this game. One big difference-maker is certainly that the thing that Pool of Radiance does best, tactical combat, it does so insanely well. And then when we get out of the weeds of the irritating minutiae of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and look at Pool of Radiance in a more holistic sense, those shocking progressive tendencies do overshadow the pedanticism in the final reckoning. Unlike so many of its contemporary CRPGs, there’s a sense about this one that its designers actually tried to walk a mile in their players’ shoes. Pool of Radiance is very solvable in comparison to an Ultima with its fragile string-of-pearls approach to plotting, and doesn’t wear out its welcome like a Bard’s Tale with its boring empty mazes and boring endless combats. If you told me that you only planned to play one 1980s-vintage CRPG in your life, I’d tell you to make it this one.

Thankfully, it’s recently become much easier to do just that. Pool of Radiance and its three sequels are now available on GOG.com along with all the other Gold Box games, ready to run on modern computers. These versions emulate the MS-DOS versions, which are faster, prettier (relatively speaking), and easier to play than the Commodore 64 originals. (Trust me, you don’t want to play 8-bit CRPGs in their 8-bit incarnations, unless you really, really enjoy swapping mounds of disks and waiting, waiting, waiting at every turn.)

I won’t lie to you: the learning curve can be a little steep with these games. To try to alleviate that just a bit, I’ll close today by offering some hard-won tips Dorte and I assembled after our own recent play-through. Crude and ugly and opaque though it may appear in the beginning, stick with it for an hour or two and you may be surprised at just how compelling Pool of Radiance can become. Sure, you might find yourself complaining the whole time you play; it’s just that kind of game. But give it a fair chance and soon you might not want to quit playing either. And that’s the real test, isn’t it?

A Few Tips On How to Best Enjoy Your Time in Phlan (and Beyond)

- Take the time (and paper and ink) to print out the paragraph book rather than relying on a digital copy. There’s something to be said for the old-school physicality of flipping through actual pages to find notes and clues. And of course if you have a physical copy it’s easy to put a tick next to the entries you’ve read. Don’t peek at entries you haven’t been asked to read, and certainly don’t just read the paragraph book straight through. This game deserves to be played fair, on its own terms.

- Plenty of modern players will want to bail as soon as they get a look at Pool of Radiance‘s bizarre-by-modern-standards keyboard-only interface. But have faith: yes, the interface is bizarre, but it’s consistent in its bizarreness. In general, you move up and down through vertical menus of nouns by using the 7 and 1 key on the numeric keypad, and select from horizontal menus of verbs by pressing the first letter of your choice. Every option available to you at any given time is always displayed onscreen, showing that SSI was by no means totally ignorant of the principles of good interface design. You can move your party about the world and move the cursor about the scene of combat using the numeric keypad as well. Within a few hours the interface will start to feel like a comfortable old shoe. No, really. Trust me.

- Especially if you’re planning to take the grand tour through all three of Pool of Radiance‘s sequels, you’ll want to think carefully about the party you put together. All of the non-human races are pretty much right out, despite their ability to multi-class and other special abilities, because they come with crippling level limits that you will likely hit well before the end of the second game. As for classes, Dorte and I did quite well with a party made up of three fighters, two clerics, and one magic user. (I’m not a big fan of thieves, although their back-stabbing ability can be fun.) Having an extra cleric on-hand to heal and fight alongside your fighters can really come in handy at the lower levels, and having two clerics to turn undead in the graveyard, one of the toughest parts of Pool of Radiance, can be a lifesaver in many combats. In the second game you get the chance to turn one of your clerics and perhaps one of your fighters into magic users by doing something called dual-classing — which, yes, is different from multi-classing. Use it to build an offensive-magic-heavy party for the later games, where spells count for more and more and swords for less and less.

- You’ll want to take your time making each individual character, re-rolling as many times as necessary to get one that will be viable in the long term; attribute scores, if not quite set in stone, can be increased only very rarely throughout the series. I recommend that each character should have a score of at least 17 in her class’s core attribute (Strength for fighters, Intelligence for magic users, Wisdom for clerics, Dexterity for thieves). Every character should have at least a 15 in Dexterity and Constitution, respectively to be able to move quickly in combat and to get bonus hit points with every level gain. And even the less critical ability scores shouldn’t be too awful; I would set 12 as an absolute floor. In order to dual-class in a later game, a character has to have at least a 15 in the core attribute of her old class and at least a 17 in that of her new; keep that in mind when planning your party and rolling your characters.

- Buy a hand mirror for each character in one of the general stores in Phlan right away. No, it’s not vanity (although some of the hairstyles in Pool of Radiance might make you think otherwise). Trust me, you’ll thank me when the time comes.

- Buy a bow and arrows for each of your fighters to go with their melee weapons. Thanks to the turn-based combat, you can switch back and forth at will on the fly, and it’s great to be able to cut down enemies at a distance.

- Stay out of taverns early in the game to avoid the classic first-time Pool of Radiance experience of getting your new party embroiled in a massive, baffling free-for-all of a bar fight that leaves them all dead and you wondering what the hell just happened. I suspect that more players have bailed permanently on the game right there than at any other point.

- Maps of all of Pool of Radiance are available in many places, including the official clue book that comes with the game if you buy it from GOG.com. Use them if you must. Before you do, though, at least take a stab at mapping the old-fashioned way. Again, the physicality of mapping on graph paper adds an ineffable something to the experience.

- When pursuing commissions, remember that you don’t need to do them in the order they’re presented to you. If one is proving too difficult, save it for later and try another.

- Dead trolls come back to life after a certain number of combat rounds. To prevent this, either kill them with fire — tricky to do at the lower levels — or keep a character standing on the exact spot where the troll died.

- Early in your travels, you’ll encounter a notoriously difficult room full of trolls. Don’t feel like you have to defeat them right there and then. Go on and build up your strength a bit more, then come back for them.

- To tackle the graveyard, your entire party needs to be equipped with silver or (preferably) magical weapons. Remember to use your cleric(s) to turn undead at the beginning of every fight involving undead monsters!

- Dead, in the sense of 0 hit points, is not usually dead in Pool of Radiance. Unless the character was hit very hard, you can usually keep her alive but unconscious for the rest of the fight by bandaging her or casting Cure Light Wounds on her. You’ll definitely want to do so, given that…

- Another one of Pool of Radiance‘s hidden poison pills is that if you pay to have a character resurrected in a temple (not like you don’t have enough money for it!) she loses 1 point of Constitution, a stiff price to pay indeed given how precious ability scores are. Think long and hard about whether that’s a price you’re willing to pay, or whether you should just try that last fight again.

- You can convert your lower-denomination coins to platinum by “Pooling” your money inside a shop, then picking it up — or some portion of it — before you leave. This gives you more buying power for less weight carried. Even better, you can store your wealth yet more efficiently as gems and jewelry that you can sell whenever you have need of a little walking-around money.

- If you have a set of the old first-edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons hardcovers lying around, or are willing to spring for digital copies, it’s a good idea to consult them when you aren’t sure what something does or is. Some of the more obscure magic items and spells in Pool of Radiance aren’t properly explained anywhere else. Dorte thought these musty old books with the cheesy covers were hilarious when I dug them out — she persisted in calling them “the nerd books” — but she did keep asking me to look stuff up in them. Which brings me to…

- Play with a partner, one of you mapping and one of you driving. Like all good things in life, a good game becomes even better when it’s shared. And wouldn’t you like to have someone to high-five when you use all your (combined) wits to win a tough fight?

(Sources: Shay Addams’s review of Pool of Radiance is found in the October 1988 Questbusters, and the Gary Gygax quote in the September 1979 Dragon.)