Just what do you do next after you’ve created an epic, career-defining masterpiece? That was the question facing Sid Meier after the release of Civilization in the waning days of 1991, after the gushing reviews and the impressive sales figures had begun pouring in to his employer MicroProse. How could he go back to making games that were merely about something when he had already made the game of everything? “Civilization was such a big game that it’s hard to find a topic that doesn’t feel as if you were going backwards,” he admitted in an interview in the summer of 1992. Anything he did next seemed destined to be an anticlimax.

Meier’s first decision about his future was an eminently sensible one: he would take a break. Asked what he was currently working on during that same interview, his reply was blunt: “Absolutely nothing! I’m going to take it easy for a while.” And truly, if anyone in the games industry deserved a timeout, it was him. Meier had maintained an insane pace for the last decade, acting as both lead designer and lead programmer on no less than 21 commercially released games, three of them — Pirates!, Railroad Tycoon, and of course Civilization — universally lauded icons whose influence has remained pervasive to this day. Indeed, those three games alone, released within five years of one another, constitute as extraordinary a creative outpouring as the field of gaming has ever known. But now, Meier was finally feeling burnt out, even as his marriage was ending — at least partially the result, no doubt, of all those years spent burning the candle at both ends. He desperately needed to catch his breath.

The Sid Meier who returned to the job months later had a new attitude toward his work. He wouldn’t try to somehow top Civilization in terms of scale and scope, but would rather use the fame and money it had brought him to work on whatever most interested him personally at any given time, whilst maintaining a much more sustainable work-life balance. Sometimes these projects would strike others — not least among them MicroProse’s management team — as almost perversely esoteric.

Never was this more the case than with his very first post-Civilization endeavor, as dramatic a departure from the expected as any game designer has ever dared to make. In fact, C.P.U. Bach wasn’t actually a game at all.

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach had long been enormously important to Meier, as he wrote in his recent memoir:

The sense I get when I listen to his work is that he’s not telling me his story, but humanity’s story. He’s sharing the joys and sorrows of his life in a more universal sense, a language that doesn’t require me to understand the specifics of his situation. I can read a book from eighteenth-century Germany, and find some amount of empathy with the historical figures inside, but there will always be a forced translation of culture, society, and a thousand other details that I can never truly understand. Bach isn’t bogged down in those things — he’s cutting straight to the heart of what we already have in common. He can reach across those three hundred years and make me, a man who manipulates electromagnetic circuits with my fingertips on a keyboard, feel just as profoundly as he made an impoverished farmer feel during a traditional rural celebration. He includes me in his story, just as I wanted to include my players in my games; we make the story together. Bach’s music is a perfect illustration of the idea that it’s not the artist that matters, but the connection between us.

Often described as the greatest single musical genius in the history of the world, Bach is as close to a universally beloved composer as one can find, as respected by jazz and rock musicians as he is in the classical concert halls. And mathematicians tend to find him almost equally alluring: the intricate patterns of his fugues illustrate the mathematical concepts that underlie all music, even as they take on a fragile beauty in their own right, outside the sound that they produce. The interior of Bach’s music is a virtual reality as compelling as any videogame, coming complete with an odd interactive quality. Meier:

He routinely used something called invertible counterpoint, in which the notes are designed to be reversible for an entirely new, but still enjoyable, sound. He also had a fondness for puzzle canons, in which he would write alternating lines of music and leave the others blank for his students — often his own children — to figure out what most logically belonged in between.

Bach even went so far as to hide codes in many of his works. Substituting place values for letters creates a numeric total of 14 for his last name, and this number is repeatedly embedded in the patterns of his pieces, as is its reverse 41, which happens to be the value of his last name plus his first two initials. His magnum opus, The Art of the Fugue, plays the letters of his name in the notes themselves (in German notation, the letter B refers to the note we call B-flat, and H is used for B-natural). At the top of one famous piece, The Well-Tempered Clavier, he drew a strange, looping flourish that scholars now believe is a coded set of instructions for how to tune the piano to play in every possible key, opening up new possibilities for variation and modulation.

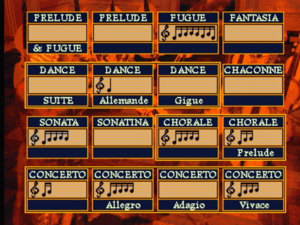

With C.P.U. Bach, Meier attempted to make a computer write and play “new” Bach compositions, working off of the known techniques of the master, taking advantage of the way that his musical patterns were, as Meier puts it, “both predictable and stunning.” Meier insists that he created the program with no intent to diminish his favorite composer, only to celebrate him. “Creating a computer [program] that creates art counts as a form of artistic expression itself,” he says.

To aid him in the endeavor, he enlisted one Jeff Briggs, a soundtrack composer at MicroProse. Together the two labored away for more than a year on the most defiantly artsy, uncommercial product of MicroProse or Sid Meier’s history. They decided to publish it exclusively on the new 3DO multimedia console, another first for the company and the designer, because they couldn’t bear to hear their creation through the often low-fidelity computer sound cards of the time; by targeting the 3DO, they guaranteed that their program’s compositions would be heard by everyone in CD-quality fidelity.

Still, the end result is a bit underwhelming, managing only to provide an ironic proof of the uniquely human genius of Johann Sebastian Bach. C.P.U. Bach generates music that is pleasantly Bach-like, but it cannot recreate the ineffable transcendence of the master’s great works.

An esoteric product for a console that would itself prove a failure, C.P.U. Bach sold horribly upon its release in 1994. But Meier doesn’t apologize for having made this least likely of all possible follow-ups to Civilization: “My only regret is that [it] is essentially unplayable today, now that the physical console has become a lost relic.” Sometimes you just have to follow your muse, in game design as in music — or, in this case, in a bit of both.

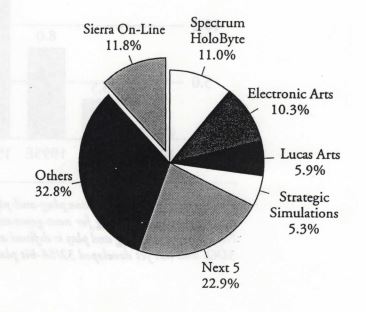

While Sid Meier was first taking a breather and then pursuing his passion project, the public image of MicroProse was being transformed by Civilization. Having made their name in the 1980s as a publisher of vehicular military simulations, they suddenly became the premiere publisher of strategy games in the eyes of many, taking over that crown from SSI, who had largely abandoned those roots to plunge deep into licensed Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs. MicroProse was soon inundated with submissions from outsiders who had played Civilization and wanted their strategy game to go out with the same label on the box as that one, thank you very much. By no means were all of the strategy games MicroProse came to publish as a result equally worthy, but the cream of the crop — titles like Master of Orion, Master of Magic, X-COM, and Transport Tycoon — were as creatively and commercially successful as the genre got during the first half of the 1990s.

The great irony about the MicroProse of this period is that these kinds of games, the ones with which the company was now most identified in the minds of gamers, were almost all sourced from outsiders while the company’s internal developers marched in a multitude of other directions. Much effort was still poured into making yet more hardcore flight simulators like the ones of old, a case of diminishing returns as the tension of the Cold War and the euphoria of the First Gulf War faded into the past. Other internal teams plunged into standup-arcade machines, casual “office games,” complicated CRPGs, and a line of multimedia-heavy adventure games that were meant to go toe-to-toe with the likes of Sierra and LucasArts.

These ventures ranged from modest successes to utter disasters in the marketplace, trending more toward the latter as time went on. The income from the outside-developed strategy games wasn’t enough to offset the losses; by 1993, the company was facing serious financial problems. In June of that year, Spectrum Holobyte, a company with a smaller product catalog but a large amount of venture capital, acquired MicroProse.

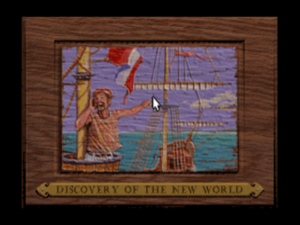

Many projects were cancelled in the wake of the acquisition, leaving many employees in limbo, waiting to find out whether their future held a new work assignment or a pink slip. One of this group was Brian Reynolds, a programmer and dedicated tabletop wargamer who had come to MicroProse to escape from his Berkeley graduate program in philosophy and been assigned to the now-cancelled adventure line. With nothing else to do, he started to tinker with a strategy game dealing with what he found to be one of the most fascinating subjects in all of human history: the colonization of the New World. Having never designed a grand-strategy game before, he used Civilization, his favorite example of the genre, as something of a crutch: he adapted most of its core systems to function within his more focused, time-limited scenario. (Although said scenario brings to mind immediately Dani Bunten Berry’s Seven Cities of Gold — a game which was ironically a huge influence on Meier’s Pirates!, Railroad Tycoon, and Civilization — Reynolds claims not to have had it much in mind when he started working on his own game. “I didn’t personally like it as a game,” he says. “It all felt like empty forests.”) Reynolds had little expectation that his efforts would amount to much of anything in the end. “I was just doing this until they laid me off,” he says. Although he was working in the same building as Meier, it never even occurred to him to ask for the Civilization source code. Instead he reverse-engineered it in the same way that any other hacker would have been forced to do.

Nevertheless, word of the prototype slowly spread around the office, finally reaching Meier. “Can you come talk to Sid about this?” Reynold’s manager asked him one day. From that day forward, Colonization was an official MicroProse project.

The powers that were at the company would undoubtedly have preferred to give the reins of the project to Meier, placing Reynolds in some sort of junior design and/or programming role. But Meier was, as we’ve already seen, up to his eyebrows in Johann Sebastian Bach at the time, and was notoriously hard to corral under any circumstances. Further, his sense of fair play was finely developed. “This is your idea,” he said to Reynolds. “You deserve to have ownership of it.” He negotiated an arrangement with MicroProse’s management whereby he would serve as a design advisor, but the project as a whole would very much remain Brian Reynold’s.

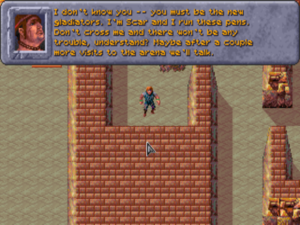

The early game of exploration and settlement is in some ways the most satisfying, being free from the micromanagement that crops up later.

Like so much in the game, the city-management screen draws heavily from Civilization, but the row of trade goods along the bottom of the screen reflects the more complex economic model.

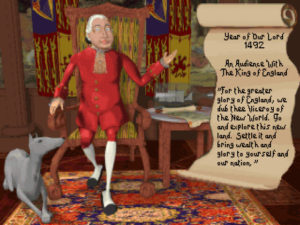

The finished Colonization lets you play as the British, the Spanish, the Dutch, or the French. You begin the game in that pivotal year of 1492, ready to explore and found your first colony in the Americas. In keeping with the historical theme, trade is extremely important — much more so than in the highly abstracted economic model employed by Civilization. Sugar, cotton, and tobacco — grown, processed, and shipped back to the Old World — are the key to your colonies’ prosperity. (Brian Reynolds has said only semi-facetiously that his intention with Colonization was to “combine together all the best things from Civilization and Railroad Tycoon — because that would make the game even better!”) Naturally, you have to deal with the Native Americans who already inhabit the lands into which you want to expand, as you do the other European powers who are jockeying for dominance. Your ultimate goal is to build a federation of colonies self-sufficient enough to declare independence from its mother country, an event which is always followed by a war. If you win said war, you’ve won the game. If, on the other hand, you lose the war, or fail to force an outcome to it by 1850, or fail to trigger it at all by 1800, you lose the game.

Even if we set aside for the moment some of the uncomfortable questions raised by its historical theme and the aspects thereof which it chooses to include and exclude, Colonization reveals itself to be a competent game but far from a great one. Sid Meier himself has confessed to some serious misgivings about the rigid path — independence by an arbitrary date or bust — down which Brian Reynolds elected to force its player:

It was a grandiose, win-or-lose proposition with the potential to invalidate hours of successful gameplay. Generally speaking, I would never risk alienating the player to that degree. It was historically accurate, however, and Brian saw it as a satisfying boss battle rather than a last-minute bait and switch, so I deferred to him. Good games don’t get made by committee.

Not only is the choice problematic from a purely gameplay perspective, but it carries unfortunate overtones of all-too-typically-American historical chauvinism in forcing the Spanish, Dutch, and French colonies to clone the experience of the British colonies that turned into the United States in order to win the game — the implication being that those colonies’ very different real histories mark them as having somehow done things wrong in contrast to the can-do Yankees.

But Colonization has plenty of other, more practical flaws. Micromanagement, that ever-present bane of so many grand-strategy games, is a serious issue here, thanks not least to the nitty-gritty complexities of the economic model; by the time you’re getting close to the point of considering independence, you’ll be so bogged down with the busywork of handing out granular work assignments to your colonists and overseeing every freight shipment back home that you’ll be in danger of losing all sense of any bigger picture. In contrast to the seamless wholeness of Civilization, Colonization remains always a game of disparate parts that don’t quite mesh. For example, the military units you can raise always seem bizarrely expensive in proportion to their potency. It takes an eternity of micro-managing tedium to build even a halfway decent military, and even when you finally get to send it out into the field you still have to spend the vast majority of your time worrying about more, shall we say, down-to-earth matters than fighting battles — like, say, whether you’ve trained enough carpenters in your cities and whether their tools are in good repair. The funnest parts of Colonization are the parts you spend the least amount of time doing.

In the end, then, Colonization never manages to answer the question of just why you ought to be playing this game instead of the more generous, open-ended, historically expansive Civilization. Computer Gaming World magazine, the industry’s journal of record at the time of the game’s release in late 1994, published a sharply negative review, saying that there was “more tedium and less care” in Colonization than in Civilization.

One might expect such a review from such an influential publication to be a game’s death knell. Surprisingly, though, Colonization did quite well for itself in the marketplace. Brian Reynolds estimates today that it sold around 300,000 copies. Although that figure strikes me as perhaps a little on the high side, there’s no question that the game was a solid success. For proof, one need only look to what Reynolds got to do next: he was given the coveted role of lead designer on Civilization II after Sid Meier, ever the iconoclast, refused it.

But here’s the odd thing: Meier’s name would appear in bold letters on the box of Civilization II, as it had on the box of Colonization before it, while that of Brian Reynolds was nowhere to be found on either. MicroProse’s marketing department had first hit upon the idea of using Meier’s name prominently back in 1987, when they’d pondered how to sell Pirates!, a game that was not only radically different from anything MicroProse had released before but was impossible to comfortably classify into any existing gaming genre. It seemed to work; Sid Meier’s Pirates! became a big hit. Since then, the official titles of most of Meier’s games had come with the same prefix. Sid Meier’s Colonization, however, was something new, marking the first time that MicroProse’s marketers assigned Meier ownership of a game he hadn’t truly designed at all. “Yes, I made suggestions along the way,” he says today, “but it had been up to Brian whether to accept them. Colonization was not Sid Meier’s game.”

And yet the name emblazoned at the top of the box stated just the opposite. Meier rationalizes this fact by claiming that “‘Sid Meier’s’ now meant ‘Sid Meier mentored and approved’ instead of ‘Sid Meier personally coded.'” But even this statement is hard to reconcile with the text on the back of the box, which speaks of “Colonization, the newest strategy game from Sid Meier [that] continues the great tradition of Civilization.” Clearly MicroProse’s marketing department, if not Meier himself, was completely eager to make the public believe that Sid Meier had designed Colonization, full stop — and, indeed, the game was received on exactly these terms by the press and public. Brian Reynolds, for his part, was happy to give his mentor all of the public credit for his work, as long as it helped the game to sell better and gave him a chance to design more games in the future. The soft-spoken, thoughtful Sid Meier, already the most unlikely of celebrities, had now achieved the ultimate in celebrity status: he had become a brand unto himself. I trust that I don’t need to dwell on the irony of this in light of his statement that “it’s not the artist that matters.”

But MicroProse’s decision to publicly credit Colonization to someone other than the person who had actually designed it is hardly the most fraught of the ethical dilemmas raised by the game. As I’ve already noted, the narrative about the colonization of the New World which it forces its player to enact is in fact the semi-mythical origin story of the United States. It’s a story that’s deeply rooted in the minds of white Americans like myself, having been planted there by the grade-school history lessons we all remember: Pilgrims eating their Thanksgiving dinner with the Indians, Bostonians dumping British tea into the ocean to protest taxation without representation, Paul Revere making his midnight ride, George Washington leading the new country to victory in war and then showing it how it ought to conduct itself in peace.

In presenting all this grade-school history as, if not quite inevitable, at least the one satisfactory course of events — it is, after all, a matter of recreating the American founding myth or losing the game — Colonization happily jettisons any and all moral complexity. One obvious example is its handling of the Native American peoples who were already living in the New World when Europeans decided to claim those lands for themselves. In the game, the Native Americans you encounter early on are an amiable if primitive and slightly dim bunch who are happy enough to acknowledge your hegemony and work for you as long as you give them cigars to smoke and stylish winter coats to wear. Later on, when they start to get uppity, they’re easy enough to put back in line using the stick instead of the carrot.

And then there’s the game’s handling of slavery — or rather its lack of same. It’s no exaggeration to say that all of the modern-day countries of North and South America were built by the sweat of slaves’ brows. Certainly the extent to which the United States in particular was shaped by what John C. Calhoun dubbed The Peculiar Institution can hardly be overstated; the country’s original sin still remains with us today in the form of an Electoral College and Senate that embody the peculiarly undemocratic practice of valuing the votes of some citizens more than those of others, not to mention the fault lines of racial animus that still fracture American politics and society. Yet the game of Colonization neatly sidesteps all of this; in its world, slavery simply doesn’t exist. Is this okay, or is it dangerous to so blithely dismiss the sins and suffering of our ancestors in a game that otherwise purports to faithfully recreate history?

Johnny L. Wilson, the editor-in-chief of Computer Gaming World, stood virtually alone among his peers in expressing concern about the thin slice of life’s rich pageant that games of the 1990s were willing and able to encompass. He alone spoke of “the preponderance of violent solutions as opposed to creative exploration and experimentation, the increasingly narrow scope of subject matter perceived as marketable, the limited nature of non-player characters and our assumptions about game players.” Unsurprisingly, then, he was the first and as it turned out the only gaming journalist of his era to address Colonization not just as a good, bad, or indifferent game in the abstract, but as a rhetorical statement about the era which it attempted to recreate, whether it wished to be such a thing or not. (As the school of Deconstructionism constantly reminds us, it’s often the works that aren’t actually trying to say anything at all about a subject which end up having the most to tell us about their makers’ attitudes toward it…) Wilson raised his concerns before Colonization was even released, when it existed only in a beta version sent to magazines like his.

Two upcoming games on the colonial era will excise slavery from the reality they are simulating: Sid Meier’s Colonization from MicroProse and Impressions’ High Seas Trader. Both design teams find the idea of slavery, much less the institution of slavery, to be repugnant, and both teams resist the idea of “rewarding” the gamer for behavior which is and was abominable.

This reminds me of the film at Mount Vernon where the narration explains that Washington abhorred slavery, so he left wording in his will so that, upon his and Martha’s deaths, his slaves would be freed. To me, that’s tantamount to saying, “I’ll correct this immoral practice as soon as it doesn’t cost me anything anymore!”

It is obvious that George didn’t find it economically viable to be moral in that circumstance. So, if slavery was such an important facet of the colonial economy that even the “father of our country” couldn’t figure out how to build a successful business without it, how do we expect to understand the period in which he lived without having the same simulated tools at our disposal? Maybe we would have some belated appreciation for those early slaves if we didn’t try to ignore the fact of their existence.

Of course, we know what the answer is going to be. The game designers will say that they “only put in the cool parts” of history. We hear that. Yet, while there is nothing wrong with emphasizing the most entertaining parts of a historical situation, there is a danger in misrepresenting that historical situation. Maybe it doesn’t add credibility to the revisionist argument that Auschwitz never happened when we remove the Waffen SS from a computer game, but what happens when someone removes Auschwitz from the map? What happens when it is removed from the history books?

Removing the horrors of history from computer games may not be a grand conspiracy to whitewash history, but it may well be a dangerous first step.

Wilson’s editorial prompted an exchange in the reader-letters section of a subsequent issue. I’d like to reprint it in an only slightly edited form here because the points raised still pop up regularly today in similar discussions. We begin with a letter from one Ken Fishkin, who takes exception with Wilson’s position.

Johnny Wilson seems to have forgotten that the primary purpose of a game is to entertain. Computer games routinely engage in drastic alterations, simplifications, and omissions of history. Railroad Tycoon omitted Chinese labor and union strife. In SimCity, the mayor is an absolute dictator who can blithely bulldoze residential neighborhoods and churches with a mere click of the mouse, and build the Golden Gate Bridge in weeks instead of decades. In Sid Meier’s Civilization, Abraham Lincoln is immortal, phalanxes can sink battleships, and religious strife, arguably the single most important factor in the history of international relations, is totally omitted. And yet Computer Gaming World gave these games its highest praise, placing all of them in its Hall of Fame!

It is hypocritical of Computer Gaming World to criticize Sid Meier’s Colonization in the same issue in which it effusively praises Sid Meier’s Civilization. Computer Gaming World used to know that computer games shouldn’t be held to the same standards of historical accuracy as a textbook.

The magazine’s editorial staff — or really, one has to suspect, Wilson himself — replied thusly:

Is it hypocritical? The same Johnny Wilson that wrote the column had an entire chapter in The SimCity Planning Commission Handbook which talked about the realities that were not simulated (along with some elaborate workarounds that would enable gamers to see how much had been abstracted) and he also questioned certain historical abstractions in [his Civilization strategy guide] Rome on 640K a Day. Do these citations seem hypocritical? Different games have different levels of perspective and different levels of abstraction. Their success or failure will always depend on the merit of their gameplay, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t consider their historical/factual underpinning as well.

Even if certain historical/real aspects have to be abstracted for the sake of gameplay, the designers have a responsibility to acknowledge, tip their hat to, or clarify those conditions which they have abstracted. When it comes to orders of battle and dominant practices, they should be addressed in some way and not ignored because they are inconvenient. We agree that a game should be balanced enough to play well, but the lessons of history should not be totally glossed over. We fear that there is a tendency of late to do just that.

Finally, we have a letter from Gilbert L. Brahms, writing in support of Wilson’s position.

Your theses are very well-taken. Computer games become nothing [more] than schlock entertainment if they strip realism from historical recreations. There is no point in presenting any [game] referring to World War II Germany without presenting Nazism in all its symbology, nay, without including the imagery which ensorcelled those desperate and gullible Germans of the time into surrendering themselves “mit ganzen Willen” to Hitler’s blandishments.

The sins of the past are not eradicated by repression; in fact, they become all the more fascinating for having become forbidden fruit. Only critical confrontation can clarify such atrocities as occurred in the 1940s and can tutor us to resist such temptations again, in ourselves as well as in others.

If, therefore, a computer game should truly aspire to become a work of art, it must fulfill both the recreative and the didactive functions inherent in all serious aesthetic productions: it must present horrible conflicts with all of their nasty details.

I’ll return to the arguments presented above in due course. Before I do that, though, I’d like to take a brief leap forward in time.

In 2008, Firaxis Games — a company founded by Sid Meier, Brian Reynolds, and Jeff Briggs — announced a new version of Colonization, which once again chose to present Native Americans as dim-witted primitives and to completely ignore the historical reality of slavery. Even before its release, Ben Fritz, a gaming blogger for Variety, loudly attacked it for having committed the vaguely defined, all-purpose crime of being “offensive.” Fritz’s blog post is neither well-argued nor well-written — “I literally exclaimed ‘holy sh*t’ out loud when I was reading an email this morning,” goes its unpromising beginning — so I won’t bother to quote more from it here. But it was a harbinger of the controversy to come, which came to dominate the critical discussion around the new Colonization to the point that its qualities as a mere game were all but ignored. Firaxis published the following terse missive in a fruitless attempt to defuse the situation:

For seventeen years the Civilization series has given people the opportunity to create their own history of the world. Colonization deals with a specific time in global history, and treats the events of that time with respect and care. As with all previous versions of Civilization, the game does not endorse any particular position or strategy – players can and should make their own moral judgments. Firaxis keeps the player at the center of the game by providing them with interesting choices and decisions to make, which has proven to be a fun experience for millions of people around the world.

Whatever its merits or lack thereof, this argument was largely ignored. The cat was now well and truly out of the bag, and many academics in particular rushed to criticize the “gamefication of imperialism” that was supposedly at the core of even the original game of Civilization. In his recent memoir, Sid Meier describes their critiques with bemusement and more than a touch of condescension.

This philosophical analysis quickly spread to my older titles — or as one paper described them, my “Althusserian unconscious manifestations of cultural claims” with “hidden pedagogical aspirations.” Pirates! wasn’t about swashbuckling, it turned out, but rather “asymmetrical and illegal activities [that] seem to undermine the hierarchical status quo while ultimately underlining it.” Even C.P.U. Bach was accused of revealing “a darker side to the ideological sources at work behind ludic techniques.”

All I can say is that our motives were sincere, and maybe these guys have a little too much time on their hands.

For all that I’m usually happy to make fun of the impenetrable writing which too many academics use to disguise banal ideas, I won’t waste space shooting those fish in a barrel here. It’s more interesting to consider the differing cultural moments exemplified by the wildly divergent receptions of the two versions of Colonization — from a nearly complete silence on the subject of the potentially problematic aspects of its theme and implementation thereof to red-faced shouting matches all over the Internet on the same subjects. Through this lens, we can see how much more seriously people came to take games over a span of fourteen years, as well as how much more diverse the people playing and writing about them became. And we can also see, of course, how the broader dialog around history changed.

Those changes have only continued and, if anything, accelerated in the time since 2008; I write these words at the close of a year in which the debates surrounding our various historical legacies have become more charged than ever. One side accuses the other of ignoring all of the positive aspects of the past and trying to “cancel” any historical figure who doesn’t live up to its fashionable modern ideals of “wokeness.” Meanwhile the opposing side accuses its antagonists of being far too eager to all too literally whitewash the past and make excuses for the reprehensible conduct of its would-be heroes. Mostly, though, the two sides prefer just to call one another nasty names.

So, rather than wading further into that morass, let’s return to the arguments I reprinted without much commentary above, applying them now not only to Colonization but also to Panzer General, the subject of my first article in this two-part series. It strikes me that the best way to unpack a subtle and difficult subject might be to consider in turn each line of argument supporting the claim that Colonization — and by implication Panzer General — are fine just as they are. We’ll begin with the last of them: Firaxis’s corporate response to the controversy surrounding the second Colonization.

Said response can be summed up as the “it’s not the game, it’s the player!” argument. It’s long been trotted out in defense of a huge swath of games with objectionable or potentially objectionable content; Peter Molyneux was using it to defend the ultra-violence in Syndicate already in 1993, and there are doubtless examples that predate even that one. The core assertion here is that the game doesn’t force the player’s hand at all — that in a game like, say, Grand Theft Auto it’s the player who chooses to indulge in vehicular mayhem instead of driving politely from place to place like a law-abiding citizen.

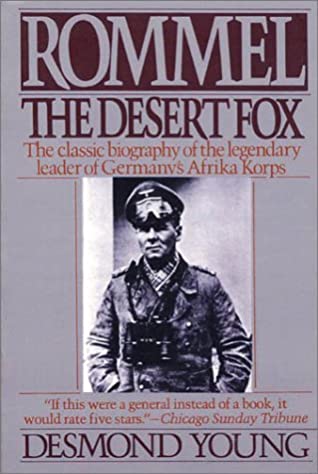

Of course, this argument can’t be used as an equally efficacious escape hatch for all games. While Panzer General will allow you to command the Allied forces if you play a single scenario, the grand campaign which is the heart of that game’s appeal only allows you to play a Nazi general, and certainly gives you no option to turn against the Nazi cause at some point, as Erwin Rommel may or may not have done, beyond the obvious remedy of shutting off the computer. But Colonization does appear to do a little better on this front, at least at first glance. As many defenders of the game are at pains to point out, you can choose to treat the Native Americans you encounter relatively gently in comparison to the European colonizers of recorded history (admittedly, not really a high bar to clear). Still, the fact does remain that you will be forced to subjugate them to one degree or another in order to win the game, simply because you need the land and resources which they control if you hope to win the final war for independence.

Here, then, we come to the fatal flaw that undermines almost all applications of this argument. Its proponents would seemingly have you believe that the games of which they speak are rhetorically neutral sandboxes, exact mirror images of some tangible objective reality. But this they are not. Even if they purport to “simulate” real events to one degree or another, they can hope to capture only a tiny sliver of their lived experience, shot through with the conscious and subconscious interests and biases of the people who make them. These last are often most clearly revealed through a game’s victory conditions, as they are in the case of Colonization. To play Colonization the “right” way — to play it as the designers intended it to be played — requires you to exploit and subjugate the people who were already in the New World millennia before your country arrived to claim it. Again, then, we’re forced to confront the fact that every example of a creative expression is a statement about its creators’ worldview, whether those creators consciously wish it to be such a thing or not. Labeling it a simulation does nothing to change this.

The handling — or rather non-handling — of slavery by Colonization is an even more telling case in point. By excising slavery entirely, Colonization loses all claim to being a simulation of real history to any recognizable degree whatsoever, given how deeply intertwined the Peculiar Institution was with everything the game does deign to depict. Just as importantly, the absence of slavery invalidates at a stroke the claim that the game is merely a neutral sandbox of a bygone historical reality for the player’s id, ego, and superego to prance through. For this yawning absence is something over which the player has no control. She isn’t given the chance to take the moral high road by refusing to participate in the slave trade; the designers have made that choice for her, as they have so many others.

I require less space to dispense with Ken Fishkin’s equating of Railroad Tycoon‘s decision not to include exploited Chinese laborers and SimCity‘s casting you in the role of an autocratic mayor with the ethical perils represented by Colonization‘s decision not to include slavery and Panzer General‘s casting you in the role of a Nazi invader. Although Fishkin expresses the position about as well as can reasonably be expected, these sorts of pedantic, context-less gotcha arguments are seldom very convincing to anyone other than the overly rigid thinkers who trot them out. I freely acknowledge that all games which purport to depict the real world do indeed simplify it enormously and choose a very specific domain to focus upon. So, yes, Railroad Tycoon as well does whitewash the history it presents to some extent. Yet the exploitation of Chinese labor in the Old West, appalling though it was, cannot compare to the pervasive legacy of American slavery and the European Holocaust in today’s world. Debaters who claim otherwise quickly start to sound disingenuous. In any discussion of this nature, space has to be allowed for degree as well as kind.

And so we arrive at Fishkin’s other argument from principle, the very place where these sorts of discussions always tend to wind up sooner or later. “The primary purpose of a game is to entertain,” he tells us. Compare that statement with these assertions of Gilbert L. Brahms: “Computer games become nothing [more] than schlock entertainment if they strip realism from historical recreations. If a computer game should truly aspire to become a work of art, it must fulfill both the recreative and the didactive functions inherent in all serious aesthetic productions: it must present horrible conflicts with all of their nasty details.” Oh, my. It seems that we’ve landed smack dab in the middle of the “are games art?” debate. What on earth do we do with this?

Many of us have been conditioned since childhood to believe that games are supposed to be fun — no more, no less. Therefore when a game crosses our path that aspires to be more than just fun — or, even more strangely, doesn’t aspire to be “fun” in the typical sense of the word at all — we can find it deeply confusing. And, people being people, our first reaction is often outrage. Three years before the second version of Colonization was released, one Danny Ledonne made Super Columbine Massacre RPG!, an earnest if rather gawkily adolescent attempt to explore the backgrounds and motivations of the perpetrators of the high-school massacre in question. A book on the same theme would have been accepted and reviewed on its merits, but the game received widespread condemnation simply for existing. Since games by definition can aspire only to being fun, Ledonne must consider it fun to reenact the Columbine massacre, right? The “games as art” and “serious games” crews tried to explain that this edifice of reasoning was built upon a faulty set of assumptions, but the two sides mostly just talked past one another.

Although the “just a game” defense may seem a tempting get-out-of-jail-free card in the context of a Panzer General or a Colonization, one should think long and hard before one plays it. For to do so is to infantilize the entire medium — to place it into some other, fundamentally different category from books and movies and other forms of media that are allowed a place at the table where serious cultural dialog takes place.

The second version of Colonization found itself impaled on the horns of these two very different sets of assumptions about games. Its excision of slavery drew howls of protest calling it out for its shameful whitewashing of history. But just imagine the alternative! As Rebecca Mir and Trevor Owens pointed out in a journal article after the hubbub had died down, the controversy we got was nothing compared to the one we would have had if Colonization had given the naysayers what many of them claimed to want: had better captured historical reality by actually letting you own and trade slaves. The arguments against the one approach are predicated on the supposition that at least some types of games are more than idle entertainments, that a game which bills itself as a reasonably accurate reenactment of colonial history and yet excises slavery from its narrative deserves to be condemned in the same terms as a book or movie which does the same; the arguments against the other are rooted in the supposition that games are just fun, and how dare you propose that it’s fun to join the slave trade. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Perhaps the only practical solution to the dilemma is that of simply not making any more versions of Colonization. No, it’s not a terribly satisfying solution, placing limits as it does on what games are allowed to do and be. Nevertheless, it’s the one that Firaxis will almost certainly choose to employ in the future.

I do want to emphasize one more time here at the end of this pair of articles that neither Panzer General nor Colonization was created with any conscious bad intent. They stem from a time when computer gaming was much more culturally homogeneous than it has become, when computer gamers were to an almost overwhelming degree affluent, stereotypically “nerdy” white males between the ages of 10 and 35. People of privilege that they were, usually immersed in the hard sciences rather than the irritatingly amorphous but more empathetic humanities, they struggled to identify with those crosscurrents of society and history outside their own. Although the wargaming subculture that spawned Panzer General and Colonization still exists, and would still receive those exact games today in the same unquestioning way, it’s vastly smaller than it used to be in proportion to the overall mass of gamers. And, again, its blind spots then and now remain venal sins at worst in the grand scale of things.

That said, I for one am happy that the trajectory of gaming since 1994 has been ever outward, both in terms of the types of people who play games and the kinds of themes and experiences those games present. Indeed, it sometimes seems to me that their very scope of possibility is half the reason we can so easily confuse one another when we try to talk about games. Certainly one person’s idea of a satisfying game can be markedly different from another’s, such that even as brilliant a mind as that of Sid Meier can have trouble containing it all. His famous categorical claim that a good game is a “series of interesting decisions” is true enough in the case of the games he prefers to play and make, but fails to reckon with the more experiential aspects of interactivity which many players find at least equally appealing. It’s thus no surprise that he offhandedly dismisses adventures games and other interactive experiences that are more tightly plotted and less zero-sum.

I’ve often wondered whether this label of “game” is really all that useful at all, whether there’s really any more taxonomical kinship between a Colonization and a Super Columbine RPG! than there is between, say, books and movies. Digital games are the ultimate form of bastard media, appropriating elements from all of the others and then slathering on top of it all the special sauce of interactivity. Perhaps someday we’ll figure out how to talk about this amorphous stew of possibility that just keeps bubbling up out of the pot we want to use to contain it; perhaps someday we’ll divide it up into a collection of separate categories of media, using those things we call “gaming genres” now as their basis. In the meantime, we’ll just have to hang on for the ride, and try not to rush to judgment too quickly when our expectations of the medium don’t align with those of others.

(Sources: the books Sid Meier’s Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games by Sid Meier with Jennifer Lee Noonan and the article “Modeling Indigenous Peoples: Unpacking Ideology in Sid Meier’s Colonization” by Rebecca Mir and Trevor Owens, from the book Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History; PC Review of August 1992; Computer Gaming World of April 1994, September 1994, November 1994, and December 1994; online sources include “How Historical Games Integrate or Ignore Slavery” by Amanda Kerry on Rock Paper Shotgun; “Colonialism is Fun? Sid Meier’s Civilization and the Gamefication of Imperialism” by CIGH Exeter on the Imperial and Global Forum; Soren Johnson’s interview with Brian Reynolds; IGN‘s interview with Brian Reynolds; Ben Fritz’s blog on Variety.

Colonization is available for digital purchase on GOG.com. C.P.U. Bach, having been made only for a long-since-orphaned console, is sadly not.)