Ultima IX

Years ago, [Origin Systems] released Strike Commander, a high-concept flight sim that, while very entertaining from a purely theoretical point of view, was so resource-demanding that no one in the country actually owned a machine that could play it. Later, in Ultima VIII, the company decided to try to increase their sales numbers by adding action sequences straight out of a platform game to their ultra-deep RPG. The results managed to piss just about everyone off. With Ultima IX: Ascension, the company has made both mistakes again, but this time on a scale that is likely to make everyone finally forget about the company’s past mistakes and concentrate their efforts on making fun of this one.

— Trent C. Ward, writing for IGN

Appalling voice-acting. Clunky dialog-tree system. Over-simplistic, poorly implemented combat system. Disjointed story line… A huge slap in the face for all longtime Ultima fans… Insulting and contemptuous.

— Julian Schoffel, writing from the Department of “Other Than That, It Was Great” at Growling Dog Gaming

The late 1990s introduced a new phenomenon to the culture of gaming: the truly epic failure, the game that failed to live up to expectations so comprehensively that it became a sort of anti-heroic legend, destined to be better remembered than almost all of its vastly more playable competition. It’s not as if the bad game was a new species; people had been making bad games — far more of them than really good ones, if we’re being honest — for as long as they had been making games at all. But it took the industry’s meteoric expansion over the course of the 1990s, from a niche hobby for kids and nerds (and usually both) to a media ecosystem with realistic mainstream aspirations, to give rise to the combination of hype, hubris, excess, and ineptitude which could yield a Battlecruiser 3000AD or a Daikatana. Such games became cringe humor on a worldwide scale, whether they involved Derek Smart telling us his game was better than sex or John Romero saying he wanted to make us his bitch.

Another dubiously proud member of the 1990s rogue’s gallery of suckitude — just to use some period-correct diction, you understand — was Ultima IX: Ascension, the broken, slapdash, bed-shitting end to one of the most iconic franchises in all of gaming history. I’ve loved a handful of the older Ultimas and viewed some of the others with more of a jaundiced eye in the course of writing these histories, but there can be no denying that these games were seminal building blocks of the CRPG genre as we know it today. Surely the series deserved a better send-off than this.

As it is, though, Ultima IX has long since become a meme, a shorthand for ludic disaster. More people than have ever actually played it have watched Noah Antwiler’s rage-drenched two-hour takedown of the game from 2012, in a video which has itself become oddly iconic as one of the founding texts (videos?) of long-form YouTube game commentary. Meanwhile Richard Garriott, the motivating force behind Ultima from first to last, has done his level best to write the aforementioned last out of history entirely. Ultima IX is literally never mentioned at all in his autobiography.

But, much though I may be tempted to, I can’t similarly sweep under the rug the eminently unsatisfactory denouement to the Ultima series. I have to tell you how this unfortunate last gasp fits into the broader picture of the series’s life and times, and do what I can to explain to you how it turned out so darn awful.

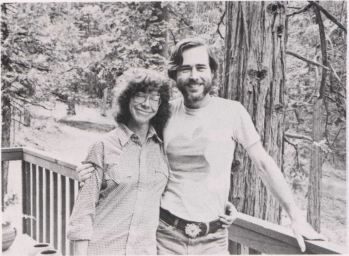

Al Remmers, the man who unleashed Lord British and Ultima upon the world, is pictured here with his wife.

The great unsung hero of Ultima is a hard-disk salesman, software entrepreneur, and alleged drug addict named Al Remmers, who in 1980 agreed to distribute under the auspices of his company California Pacific a simple Apple II game called Akalabeth, written by a first-year student at the University of Texas named Richard Garriott. It was Remmers who suggested crediting the game to “Lord British,” a backhanded nickname Garriott had picked up from his Dungeons & Dragons buddies to commemorate his having been born in Britain (albeit to American parents), his lack of a Texas drawl, and, one suspects, a certain lordly manner he had begun to display even as an otherwise ordinary suburban teenager. Thus this name that had been coined in a spirit of mildly deprecating irony became the official nom de plume of Garriott, a young man whose personality evinced little appetite for self-deprecation or irony. A year after Akalabeth, when Garriott delivered to Remmers a second, more fully realized implementation of “Dungeons & Dragons on a computer” — also the first game into which he inserted himself/Lord British as the king of the realm of Britannia — Remmers came up with the name of Ultima as a catchier alternative to Garriott’s proposed Ultimatum. Having performed these enormous semiotic services for our young hero, Al Remmers then disappeared from the stage forever. By the time he did so, he had, according to Garriott, snorted all of his own and all of the young game developer’s money straight up his nose.

The Ultima series, however, was off to the races. After a brief, similarly unhappy dalliance with Sierra On-Line, Garriott started the company Origin Systems in 1983 to publish Ultima III. For the balance of the decade, Origin was every inch The House That Ultima Built. It did release other games — quite a number of them, in fact — and sometimes these games even did fairly well, but the anchor of the company’s identity and its balance sheets were the new Ultima iterations that appeared in 1985, 1988, and 1990, each one more technically and narratively ambitious than the last. Origin was Lord British; Origin was Ultima; Lord British was Ultima. Any and all were inconceivable without the others.

But that changed just a few months after Ultima VI, when Origin released a game called Wing Commander, designed by an enthusiastic kid named Chris Roberts who also had a British connection: he had come to Austin, Texas, by way of Manchester, England. Wing Commander wasn’t revolutionary in terms of its core gameplay; it was a “space sim” that sought to replicate the dogfighting seen in Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, part of a sub-genre that dated back to 1984’s Elite. What made it revolutionary was the stuff around the sim, a story that gave each mission you flew meaning and resonance. Gamers fell head over heels for Wing Commander, enough so to let it do the unthinkable: it outsold the latest Ultima. Just like that, Origin became the house of Wing Commander and Ultima — and in that order in the minds of many. Now Chris Roberts’s pudgy chipmunk smile was as much the face of the company as the familiar bearded mien of Lord British.

The next few years were the best in Origin’s history, in a business sense and arguably in a creative one as well, but the impressive growth in revenues was almost entirely down to the new Wing Commander franchise, which spawned a bewildering array of sequels, spin-offs, and add-ons that together constituted the most successful product line in computer gaming during the last few years before DOOM came along to upend everything. Ultima produced more mixed results. A rather delightful spinoff line called The Worlds of Ultima, moving the formula away from high fantasy and into pulp adventure of the Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells stripe, sold poorly and fizzled out after just two installments. The next mainline Ultima, 1992’s Ultima VII: The Black Gate, is widely regarded today as the series’s absolute peak, but it was accorded a surprisingly muted reception at the time; Charles Ardai wrote in Computer Gaming World how “weary gamers [are] sure that they have played enough Ultima to last them a lifetime,” how “computer gaming needs another visit to good old Britannia like the movies need another visit from Freddy Krueger.” That year the first-person-perspective, more action-oriented spinoff Ultima Underworld, the first project of the legendary Boston-based studio Looking Glass, actually sold better than the latest mainline entry in the series, another event that had seemed unthinkable until it came to pass.

Men with small egos don’t tend to dress themselves up as kings and unironically bless their fans during trade shows and conventions, as Richard Garriott had long made a habit of doing. It had to rankle him that the franchise invented by Chris Roberts, no shrinking violet himself, was by now generating the lion’s share of Origin’s profits. And yet there could be no denying that when Electronic Arts bought the company Garriott had founded on September 25, 1992, it was primarily Wing Commander that it wanted to get its hands on.

So, taking a hint from the success of not only Wing Commander but also Ultima Underworld, Garriott decided that the mainline games in his signature series as well had to become more streamlined and action-oriented. He decided to embrace, of all possible gameplay archetypes, the Prince of Persia-style platformer. The result was 1994’s Ultima VIII: Pagan, a game that seems like something less than a complete and total disaster today only by comparison with Ultima IX. Its action elements were executed far too ineptly to attract new players. And as for the Ultima old guard, they would have heaped scorn upon it even if it had been a good example of what it was trying to be; their favorite nickname for it was Super Ultima Bros. It stank up the joint so badly that Origin chose toward the end of the year not to even bother putting out an expansion pack that its development team had ready to go, right down to the box art.

The story of Ultima IX proper begins already at this fraught juncture, more than five years before that game’s eventual release. The team that had made Ultima VIII was split in two, with the majority going to work on Crusader: No Remorse, a rare 1990s Origin game that bore the name of neither Ultima nor Wing Commander. (It was a science-fiction exercise that wound up using the Ultima VIII engine to better effect, most critics and gamers would judge, than Ultima VIII itself had.) Just a few people were assigned to Ultima IX. An issue of Origin’s internal newsletter dating from February of 1995 describes them as “finishing [the] script stage, evaluating technology, and assembling a crack development team.” Origin programmer Mike McShaffry:

Right after the release [of Ultima VIII], Origin’s customer-service department compiled a list of customer complaints. It weighed about ten pounds! The Ultima IX core team went over this with a fine-toothed comb, and we decided along with Richard that we should get back to the original Ultima design formula. Ultima IX was going to be a game inspired by Ultimas IV and VII and nothing else. When I think of that game design I get chills; it was going to be awesome.

As McShaffry says, it was hoped that Ultima IX could rejuvenate the franchise by righting the wrongs of Ultima VIII. It would be evolutionary rather than revolutionary, placing a modernized gloss on what fans had loved about the games that came before: a deep world simulation, a whole party of adventurers to command, lots and lots of dialog in a richly realized setting. The isometric engine of Ultima VII was re-imagined as a 3D space, with a camera that the player could pan and zoom around the world. “For the first time ever, you could see what was on the south and east side of walls,” laughs McShaffry. “When you walked in a house, the roof would pop off and you could see inside.” Ultima IX was also to be the first entry in the series to be fully voice-acted. Origin hired one Bob White, an old friend with whom Richard Garriott had played Dungeons & Dragons as a teenager, to turn Garriott’s vague story ideas into a proper script for the voice actors to perform.

Garriott himself had been slowly sidling back from day-to-day involvement with Ultima development since roughly 1986, when he was cajoled into accepting that the demands of designing, writing, coding, and even drawing each game all by himself had become unsustainable. By the time that Ultima VII and VIII rolled around, he was content to provide a set of design goals and some high-level direction for the story only, while he busied himself with goings-on in the executive suite and playing Lord British for the fans. This trend would do little to reverse itself over the next five years, notwithstanding the occasional pledge from Garriott to “discard the mantle of authority within even my own group so I can stay at the designer level.” (Yes, he really talked like that.) This chronic reluctance on the part of Ultima IX’s most prominent booster to get his hands dirty would be a persistent issue for the project as the corporate politics surrounding it waxed and waned.

For now, the team did what they could with the high-level guidance he provided. Garriott had come to see Ultima IX as the culmination of a “trilogy of trilogies.” Long before it became clear to him that the game would probably mark the end of the series for purely business reasons, he intended it to mark the end of an Ultima era at the very least. He told Bob White that he wanted him to blow up Britannia at the conclusion of the game in much the same way that Douglas Adams had blown up every possible version of the Earth in his novel Mostly Harmless, and for the same reason: in order to ensure that he would have his work cut out for him if he decided to go back on his promise to himself and try to make yet another sequel set in Britannia. By September of 1996, White’s script was far enough along to record an initial round of voice-acting sessions, in the same Hollywood studio used by The Simpsons.

But just as momentum seemed to be coalescing around Ultima IX, two other events at Origin Systems conspired to derail it. The first was the release of Wing Commander IV: The Price of Freedom in April of 1996. Widely trumpeted as the most expensive computer game yet made, the first with a budget that ran to eight digits, it marked the apex of Chris Roberts’s fixation on making “interactive movies,” starring Mark Hamill of Star Wars fame and a supporting cast of Hollywood regulars acting on a real Hollywood sound stage. But it resoundingly failed to live up to Origin’s sky-high commercial expectations for it; at three times the cost of Wing Commander III (which had also featured Hamill), it generated one-third as many sales. This failure threw all of Origin Systems into an existential tizzy. Roberts and few of his colleagues left after being informed that the current direction of the Wing Commander series was financially untenable, and everyone who remained behind wondered how they were going to keep the lights on now that both of Origin’s flagship franchises had fallen on hard times. The studio went through several rounds of layoffs, which deeply scarred the communal psyche of the survivors; Origin would never fully recover from the rupture, never regain its old confident swagger.

Partially in response to this crisis, another project that bore the name of Ultima saw its profile elevated. Ultima Online was to be the fruition of a dream of a persistent multiplayer fantasy world that Richard Garriott had been nursing since the 1980s. In 1995, when rapidly spreading Internet connectivity combined with the latest computer hardware were beginning to make the dream realistically conceivable, he had hired Raph and Kristen Koster, a pair of Alabama graduate students who were stars of the textual-MUD scene, to come to Austin and build a multiplayer Britannia. Ultima Online had at first been regarded more as a blue-sky research project than a serious effort to create a money-making game; it had seemed the longest of long shots, and was barely tolerated on that basis by the rest of Origin and EA’s management.

But the collapse of the industry’s “Siliwood” interactive-movie movement, as evinced by the failure of Wing Commander IV, had come in the midst of a major commercial downturn for single-player CRPGs like the traditional Ultimas as well. Both of Origin’s core competencies looked like they might not be applicable to the direction that gaming writ large was going. In this terrifying situation, Ultima Online began to look much more appealing. Online gaming was growing apace alongside the young World Wide Web, even as the appeal of Ultima Online’s new revenue model, whereby customers could be expected to pay once to buy the game in a box and then keep paying every single month to maintain access to the online multiplayer Britannia, hardly requires further clarification. Ultima Online, it seemed, might be the necessary future for Origin Systems, if it was to have a future at all. These incipient ideas were given a new impetus over the last four months of 1996, when two other massively-multiplayer-online-role-playing games — a term coined by Richard Garriott — were launched to a cautiously positive reception. This relative success came even though neither 3DO’s Meridian 59 nor Sierra’s The Realm was anywhere near as technically and socially sophisticated as the Kosters intended Ultima Online to be.

By the beginning of 1997, the Ultima Online developers were closing in on a wide-scale beta test, the last step before their game went live for paying customers. Rather cheekily, they asked the fans who had been following their progress closely on the Internet to pony up $5 each months in advance for the privilege of becoming their guinea pigs; cheeky or not, tens of thousands of fans did so. This evidence of pent-up demand convinced the still-tiny team’s managers to go all-in on their game. In March of 1997, the nine Ultima Online people were moved into the office space currently occupied by the 23 people who were making Ultima IX. The latter were ordered to set aside what they were working on and help their new colleagues get their MMORPG into shape for the beta test. In the space of a year, Ultima Online had gone from an afterthought to a major priority, while Ultima IX had done precisely the opposite. Although both games were risky projects, it looked like Ultima Online might be the better match for where gaming was going.

The conjoined team got Ultima Online to beta that summer and into boxes in stores that September, albeit not without a certain degree of backbiting and infighting. (The Ultima Online people regarded the Ultima IX people as last-minute jumpers on their bandwagon; the Ultima IX people were equally resentful, suspecting — and not without some justification — that their own project would never be restarted, especially if the MMORPG took off as Origin hoped it would.) Although dogged throughout its early years by technical issues and teething problems of design, the inevitable niggles of a pioneer, Ultima Online was soon able to attract a fairly stable base of some 90,000 players, each of whom paid Origin $10 per month to roam the highways and byways of Britannia with others.

It became a vital revenue stream for a studio that otherwise didn’t have much of anything going for it. The same year as Ultima Online’s launch, Wing Commander: Prophecy, an attempt to reboot the series for this post-Chris Roberts, post-interactive-movie era, was released to sales even worse than those of Wing Commander IV, marking the anticlimactic end of the franchise that had been the biggest in computer gaming just a few years earlier. Any petty triumph Richard Garriott might have been tempted to feel at having seen his Ultima outlive Wing Commander was undermined by the harsh reality of Origin’s plight. The only single-player games now left in development at the incredible shrinking studio were the Jane’s Longbow hardcore helicopter simulations, entries in yet another genre that was falling on hard commercial times.

Electronic Arts was taking a more and more hands-on role as Origin’s fortunes declined. A pair of executives named Neil Young and Chris Yates had been parachuted in from the Silicon Valley mother ship to become Origin’s new General Manager and Chief Technical Officer respectively. Much to the old team’s surprise, they opted to restart Ultima IX in late 1997. They read the massive success of the CRPG-lite Diablo as a sign that the genre might not be as dead to gamers as everyone had thought, especially if it was given an audiovisual facelift and, following the example of Diablo, had its gameplay greatly simplified. A producer named Edward Alexander Del Castillo was hired away from Westwood Studios, where he had been in charge of the mega-selling Command & Conquer series of real-time-strategy games. If anyone could figure out how to make the latest single-player Ultima seem relevant to fans of more recent gameplay paradigms, it ought to be him.

What with the ongoing layoffs and other forms of attrition, fewer than half of the 23 people who had been working on Ultima IX prior to the Ultima Online interregnum returned to the project. Those who did sifted through the leavings of their earlier efforts, trying to salvage whatever they could to suit Del Castillo’s new plans for the project. He re-imagined the game into something that looked more like the misbegotten Ultima VIII than the hallowed Ultima VII. The additional party members were done away with, as was the roving camera, and the visuals and interface came to mimic third-person action games like the hugely popular Tomb Raider. Del Castillo convinced Richard Garriott to come up with a new story outline in which Britannia didn’t get destroyed, an event which might now read as confusing, given that people would presumably still be logging into Ultima Online to adventure there after this single-player game’s release. In the new script, as fleshed out once again by Bob White, the player’s goal would be to become one with the villainous Guardian, who would turn out to be the other half of himself, and rise as one being with him to a higher plane of existence; thus the “ascension” of the eventual subtitle. It felt like the older games in the way it flirted with spirituality, for all that it did so a bit clumsily. (Garriott stated in a contemporaneous interview that “I’m enamored with Buddhism right now,” as if it was a catchy tune he’d heard on the radio; this isn’t the way spirituality is supposed to work.)

In May of 1998, Origin brought the work in progress to the E3 trade show. It did not go well. The old-school fans were appalled by the teaser video the team brought with them, featuring lots of blood-splattered carnage choreographed to a thrash-metal soundtrack, more DOOM than Ultima. Del Castillo got defensive and derisive when confronted with their criticisms, making a bad situation worse: “Ultimas are not about stick men and baking bread. Ultimas are about using the computer as a tool to enhance the fantasy experience. To take away the clumsy dice, slow charts and paper and give you wonderful gameplay instead. They were never meant to mimic paper RPGs; they were meant to exceed them.” In addition to being a straw-man argument, this was also an ahistorical one: like all of the first CRPGs, Richard Garriott’s first Ultima games had been literal, explicit attempts to put the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons game he loved on a computer. Internet forums and Usenet message boards burned with indignation in the weeks and months after the show.

Those who could abandoned the increasingly dysfunctional ship. Bob White bailed for John Romero’s new company Ion Storm, where he became a designer on Deus Ex. Then Del Castillo was fired, thanks to “philosophical differences” with Richard Garriott. Lead programmer Bill Randolph recalls the last words Del Castillo said to him on the day he left: “They don’t care about the game. They’re just going to shove it out the door unfinished.”

Garriott announced, not for the first time, that he intended to step in and take a more hands-on role at this juncture, but that never amounted to much beyond an unearned “Director” credit. “You know, he had a lot of other obligations, and he had a lot going on, and a lot of other interests that he was pursuing too,” says Randolph by way of apologizing for his boss. Be that as it may, Garriott’s presence on the org chart but non-presence in the office resulted in a classic power vacuum; everyone could see that the game was shaping up to be hot garbage, but no one felt empowered to take the steps that were needed to fix it. Turnover continued to be a problem as Origin continued to take on water. Few of the people left on the team had any experience with or emotional connection to the previous single-player Ultima games.

Del Castillo’s ominous prophecy came true on November 26, 1999, after a frantic race to the bottom, during which the exhausted, demoralized team tried to hammer together a bunch of ill-fitting fragments into some semblance of a playable game in time for EA’s final deadline. They met the deadline — what other choice did they have? — but the playable game eluded them.

I don’t want to spend a lot of time here excoriating Ultima IX in detail, the way I did Omikron: The Nomad Soul in my very last article. I nominated Omikron for Worst Game of 1999, but Ultima IX has run away with that prize. Although I found Omikron to be deliriously lousy, it was at least lousy in a somewhat interesting way, the product of a distinctive if badly misguided vision. Ultima IX, alas, doesn’t have even that much going for it. Whatever original creative vision it might once have evinced has been so thoroughly ground away by outside pressures and corporate interference that it’s not even fun to make fun of. As far as kind words go, all I can come up with is that the box looks pretty good — a right proper Ultima box, that is — and some of the landscape vistas are impressive, as long as you don’t spoil the experience by trying to do anything as you’re looking at them. Everything else is pants.

Imagine the worst possible implementation of every single thing Ultima IX tries to do and be, and you’ll have a reasonably good picture of what this game is like. Even 26 years later, it remains a technical disaster: crashing constantly, full of memory leaks that gradually degrade performance as you play. Characters and monsters have an unnerving habit of floating in the air, their feet at the height of your eyes; corpses — and not undead ones — sometimes inexplicably keep on fighting instead of staying put on the ground (or in mid-air, as the case may be). These things ought to be funny in a “so bad it’s good” kind of way, but somehow they aren’t. Absolutely nothing about this game is entertaining — not the cutscenes that were earmarked for an earlier incarnation of the script only to be shoehorned into this one, not the countless other parts of the story that just don’t make any sense. Nothing feels right; the physics of the world are subtly off even when everything is ostensibly working correctly. The fixed camera always seems to be pointing precisely where you don’t want it to, and combat is just bashing away on the mouse button, an action which feels peculiarly disconnected from what you see your character doing onscreen.

Of course, one can make the argument that Ultima wasn’t really about combat even in its best years; Ultima VII’s combat system is almost as bad as this one, and that hasn’t prevented that game from becoming the consensus choice for the peak of the entire series. What well and truly pissed off the series’s hardcore fan base back in the day was how badly this game fails as an Ultima. A game that was once supposed to correct the ill-advised misstep that had been Ultima VIII and mark a return to the franchise’s core values managed in the end to feel like even more of a betrayal than its predecessor. This final installment of a series famous for the freedom it affords its player is a rigidly linear slog through underwhelming plot point after underwhelming plot point. Go to the next city; perform the same set of rote tasks as in the last one; rinse and repeat. If you try too hard to do something other than that which has been foreordained for you, you just end up breaking the game and having to start over.

And yet it’s not as if Ultima IX doesn’t try to exploit its heritage. In fact, no Ultima that came before was as relentlessly self-referential as this one. You create your character by answering questions from a gypsy fortuneteller, like in the iconic opening of Ultima IV. The plot hinges on yet another corruption of the Virtues, like in the fourth, fifth, and sixth games. You visit Lord British in his castle, like in every Ultima ever. There you find a newly constructed museum celebrating your exploits, from your defeat of the evil wizard Mondain in Ultima I to your recent difficulties with the Guardian, the overarching villain of this third trilogy of trilogies. The foregrounded self-referentiality quickly becomes much, much too much; it gives the game a past-its-time, sclerotic feel that must have thoroughly nonplussed any of the new generation CRPG players, weaned on Baldur’s Gate and Might and Magic VI and VII, who might have been unwise enough to pick this game up instead of Planescape: Torment, its primary competition that Christmas season of 1999. Ultima IX is like that boring old man who can’t seem to shut up about all the cool stuff he used to get up to.

But at the same time, and almost paradoxically, Ultima IX is utterly clueless about its heritage, all too obviously the product — and I use that word advisedly — of people who knew Ultima only as a collection of tropes. I don’t really mean all the little details that it gets wrong, which the fans have, predictably enough, cataloged at exhaustive length. When it comes to questions of continuity, I’m actually prepared to extend quite a lot of slack to a series that went from games written by a teenager all by himself in his bedroom to multi-million-dollar productions like this one over the course of almost twenty years of tempestuous technical and cultural evolution in the field of gaming. Rather than the nitpicky details, it’s the huge, fundamental things that this game and its protagonist seem not to know that flummox me. (Remember, the official line is that the Avatar is the same guy through all nine mainline Ultima games and all of the spinoffs to boot.) At one point in this game, the Avatar encounters the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, the object around which revolved the plot of Ultima IV, probably the best-remembered and most critically lauded entry in the series except for Ultima VII. “The Codex of Ultimate Wisdom?” he repeats in a confused tone of voice, as if he’s sounding out the words as he goes. As Noah Antwiler said in my favorite quip from his video series, this is like the pope asking someone if she happens to know what this Bible thing is that the priests around him keep banging on about.

The most famous meme that came out of Antwiler’s videos is another example of the Avatar’s slack-jawed cluelessness. “What’s a paladin?” he asks the first person he meets in Trinsic, the town of Honor which he has visited many times in the course of his questing. You have to hear him say it, in the voice of a bored television announcer, to fully appreciate it. (Like everything else in this game, the voice-acting, which had to be redone at the last minute to fit the new script, is uniformly atrocious, the output of people who all too clearly have no idea what they’re saying or why they’re saying it. Lord British sounds like a doddering old fool, inadvertently mirroring the state of the series by this point.)

You can make excuses for the existence of some of this stuff, if not the piss-poor execution. Origin obviously felt a need to make Ultima IX comprehensible and accessible to new players, coming as it did fully five and a half years after its predecessor. Lots of people had joined the gaming hobby over those years, and some of the old-timers had left it. But such excuses didn’t keep the people who were most invested in the series from seeing it as a slap to the face. “What’s a paladin?” indeed. They felt as if a treasured artifact of their childhood had been stolen and desecrated by a bunch of philistines who didn’t know an ankh from a hole in the ground. Origin ended up with the worst of all worlds: a game that felt too wrapped up in its lore to live and breathe for newcomers, even as it felt insultingly dumbed-down to the faithful who had been awaiting it with bated breath since 1994.

Any lessons we might hope to draw from this fiasco are, much like the game itself, almost too banal to be worth discussing. But, for the record:

- No game can be all things to all people.

- Development teams need a clear leader with a clear vision.

- Checking off a list of bullet points sent down from marketing does not a good game make.

- When the design goals do change radically, it’s often better to throw everything out and start over from scratch than to keep retro-fitting bits and pieces onto the Frankenstein’s monster.

- It’s better to release a good game late than a bad game on time.

Beginning with Ultima VIII, the series had begun to chase trends rather than to blaze its own trails. This game, despite all the good intentions with which it was begun, doubled down on that trend in the end. Even if the execution had been better, it would still have felt like a pale shadow of the earlier Ultima games, the ones that had the courage of their convictions. It’s not just a bad game; it’s a dull, soulless one too. If the Ultima series had to go out on a sour note, it would have been infinitely nicer to see it blow itself up in some sort of spectacular failure rather than ending in this flaccid fashion. Origin’s Neil Young could have learned a lesson from his musical namesake: “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.”

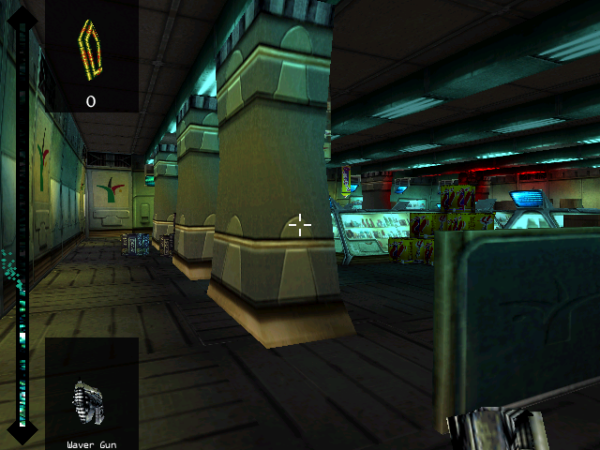

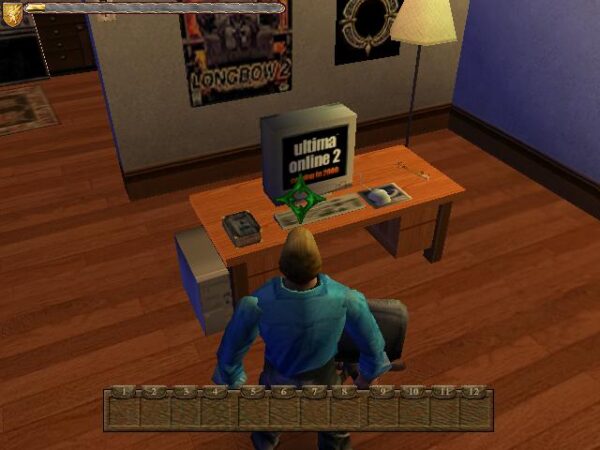

You start out in your house on Earth, even though this directly contradicts the ending of Ultima VIII.

The gypsy fortuneteller makes a return to help you choose a class and send you on your way to Britannia.

As you have probably surmised, Ultima IX did not do well in the marketplace. There was never any serious discussion of continuing the single-player series after it was greeted with bad reviews and worse sales. In fact, it managed not only to kill the series to which it belonged but for all intents and purposes the studio that had always been so closely identified with it as well. It was the last single-player game ever to be completed at Origin Systems.

Officially speaking, Origin continued to exist for another four years after it, but only as an MMORPG house. Right about the same time that Ultima IX was reaching stores, Ultima Online was actually ceding its crown as the biggest MMORPG of all to EverQuest. Nevertheless, in a bull market for shared worlds like these in general amidst the first wave of widespread broadband-Internet adoption, Ultima Online’s raw numbers still increased, reaching as many as 250,000 subscribers in early 2003. But the numbers started to go the other way thereafter as the MMORPG field became ever more crowded with younger, slicker entrants. Inevitably, there came a day in February of 2004 when it no longer made sense to EA to keep an office open in Austin just to support a single aged and declining online game. And so the story of Origin Systems came to its belated, scarcely noticed end, a decade after its best years were over.

By then, Richard Garriott was long gone; he had left Origin in March of 2000. His subsequent career did little to prove that his dilettantish approach to the later Ultima games had been a fluke. He dabbled in gaming only in fits and starts, most notably by lending his name to several more MMORPGs. As also happened with his old Origin sparring partner Chris Roberts, an unfortunate whiff of grift came to attach itself to him; I tend to think that it’s born more of carelessness in his choice of projects and associates than guile in his case, but that doesn’t make it any more pleasant to witness. Shroud of the Avatar, his Kickstarter-funded would-be second coming of Ultima Online, produced more than its fair share of broken promises and ethical questions about its pay-to-win focus during the 2010s. More recently, he has talked up an MMORPG based on blockchain technology (Lord help us!) that now appears unlikely to turn into anything at all. It seems abundantly plain that his heart hasn’t really been in making games for many years now. One hopes he will finally be content just to retire from an industry that has long since passed him by.

There’s something a little sad about watching Richard Garriott play the hits in his Lord British get-up as he closes in on retirement age.

However cheerless of a conclusion it might be, this very last article about Richard Garriott and Ultima marks a milestone for these histories. I’ve genuinely loved some of the Ultima games I’ve played these past fifteen years: Ultima I for its irrepressible teenage-Dungeonmaster enthusiasm, Ultima VII for its literary and thematic audacity, Ultima Underworld for its bold spirit of innovation. Most of all, I found myself loving the rollicking Worlds of Ultima games, two of the least played, least remembered entries in the series. (By all means, go check them out if you haven’t tried them!) As for the rest — at least the ones that came before Ultima VIII — I can see their place in history and see why others love or once loved them, even if I do also see them more as artifacts of their time than timeless.

But such carping is almost irrelevant to the cultural significance of Ultima. Richard Garriott had a huge impact on thousands upon thousands of people through Ultima IV in particular, a game which caused many of its young players to think seriously about the nature of morality and their place in the world for the very first time. Coming from a fellow not much older than they were, raised on the same sci-fi flicks and fantasy fiction that they were consuming, moral philosophy felt more real and relevant than it did when it was taught to them in school. Small wonder that so many of them still adore him for what his work meant to them all those years ago, still rush to defend him whenever a curmudgeon like myself points out his feet of clay. And that’s fine; we need to be clear-eyed about things sometimes, but at other times we just need our heroes.

So, let us bid a fond farewell to Richard Garriott — or, if you insist, Lord British, the virtuous king of Britannia. His legacy as one of gaming’s greatest visionaries is secure.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Explore/Create: My Life in Pursuit of New Frontiers, Hidden Worlds, and the Creative Spark by Richard Garriott with David Fisher; Through the Moongate: The Story of Richard Garriott, Origin Systems Inc. and Ultima, in two parts by Andrea Contato; Ultima IX: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide; Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay. Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of December 6 1991, February 10 1995, and September 20 1996; Next Generation of March 1998; Computer Gaming World of September 1992 and February 2000.

Online sources include “Ultima IX Nitpicks on the Tapestry of the Ages” on Hacki’s Ultima Page; Noah Anwiler’s video lacerations of Ultima IX; the Ultima Codex’s “Development History of Ultima IX“; Ultima Codex interviews with Mike McShaffry and Bill Randolph; an old GameSpot interview with McShaffry; Julian Schoffel’s Ultima IX retrospective for Growling Dog Games; a December 1999 group chat with some of the Ultima IX team; Desslock’s October 1998 interview with Richard Garriott for GameSpot; Trent C. Ward’s review of Ultima IX for IGN; KiraTV’s documentary about Shroud of the Avatar (but do be aware that the first part of this video uncritically regurgitates the legend rather than the reality of Richard Garriott’s pre-millennial career).

Where to Get It: Ultima IX: Ascension is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.

Omikron: The Nomad Soul

The idea of being in the body of a guy and making love to his wife — when she believes you’re her husband, even though you’re not — was a very strange position to be in. That’s exactly the kind of thing I try to explore in all my games today.

— David Cage, speaking from the Department of WTF

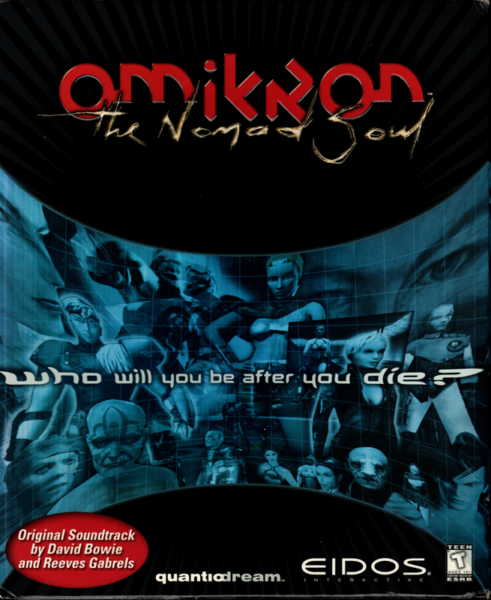

The French videogame auteur David Cage has been polarizing critics and gamers for more than a quarter-century with his oddly retro-futurist vision of the medium. He believes that games need to cease prioritizing “action” at the expense of “emotion,” a task which they can best accomplish, according to him, by embracing the aesthetics, techniques, and thematic concerns of cinema. You could lift a sentence or a paragraph from many a post-millennial David Cage interview, drop it into an article from the “interactive movie” boom of the mid-1990s, and no one would notice the difference. The interactive movie is as debatable a proposition today as it was back then; still more debatable in many cases has been Cage’s execution of it. Still, he must be doing something right: he’s been able to keep his studio Quantic Dream alive all these years, making big-budget story-focused single-player games in an industry which hasn’t always been terribly friendly toward such things.

Cage’s very first and least-played game was known as simply The Nomad Soul in Europe, as Omikron: The Nomad Soul in North America; I’ll go with the latter name here, because that’s the one under which you can still find it on digital storefronts today. Released in 1999, it’s both typical and atypical of his later oeuvre. We see the same emphasis on story, the same cinematic sensibility, the same determination to eliminate conventional failure states, even the same granular obsessions with noirish law enforcement, the transmigration of souls, and, well, Blade Runner. But it’s uniquely ambitious in its gameplay, despite having been made for far less money than any other David Cage production. It’s a combination of Beneath a Steel Sky with Tomb Raider with Mortal Kombat with Quake, with a soundtrack provided by David Bowie. If you’re a rambunctious thirteen-year-old, like our old friends Ian and Nigel, you might be thinking that that sounds awesome. If you’re older and wiser, the alarm bells are probably already ringing in your head. Such cynicism is sadly warranted; no jack of all trades has ever mastered fewer of them than Omikron.

David Cage was born in 1969 as David de Gruttola, in the Alsatian border town of Mulhouse, a hop and a skip away from both Germany and Switzerland. He discovered that he had a talent for music at an early age. By the time he was fifteen, he could play piano, guitar, bass, and drums, and had started doing session gigs for studios as far away as Paris. He moved to the City of Light as soon as he finished school. By saving his earnings as a session musician, he was eventually able to buy an existing music studio there that went under the name of Totem. A competent composer as well as instrumentalist, he provided jingles for television commercials and the like. These kinds of ultra-commoditized music productions were rapidly computerizing by the end of the 1980s; it was much cheaper and faster to knock out a simple tune with a bank of keyboards and a MIDI controller than it was to hire a whole band to come in or to overdub the parts one by one on “real” instruments. Thus Totem became David de Gruttola’s entrée into the world of digital technology.

Totem also brought Gruttola into the orbit of the French games industry for the first time. He provided music and/or sound for five games between 1994 and 1996: Super Dany, Timecop, Cheese Cat-astrophe, Versailles 1685, and Hardline. Roll call of mediocrity though this list may be, it awakened a passion in him. By now in the second half of his twenties, he was still very young by most standards, but old enough to realize that he would never be more than a competent musician or composer. Games, though… games might be another story. Never one to shrink unduly from the grandiose view of himself and his art, he would describe his feelings in this way a decade later:

I remember how many possibilities suddenly opened up because of this new technology. I saw it as a new means of expression, where the world could be pushed to its limits. It was my way of exploring new horizons. I felt like a pioneer filmmaker at the start of the twentieth century: grappling with basic technology, but also being aware that there is everything left to invent — in particular, a new language that is both narrative and visual.

Thus inspired, Gruttola wrote a script of 200 to 250 pages, about a gamer who gets sucked through the monitor into an alternative universe, winding up in a futuristic dystopian city known as Omikron. The script was “naïve but sincere,” he says. “I was dreaming of a game with an open-world city where I could go wherever I wanted, meet anybody, use vehicles, fight, and transfer my soul into another body.” (Ian and Nigel would surely have approved…)

Being neither a programmer nor a visual artist himself, he convinced a handful of friends to help him out. They first tried to implement Omikron on a Sony PlayStation, only to think better of it and turn it into a Windows game instead. Late in 1996, more excited than ever, Gruttola offered his friends a contract: he would pay them to work on the game exclusively for the next six months, using the money he had made from his music business. At the end of that time, they ought to have a decent demo to shop around to publishers. If they could land one, they would be off to the races. If they couldn’t, they would put their ludic dreams away and go back to their old lives. Five of the friends agreed.

So, they made a 3D engine from scratch, then made a first pass at their Blade Runner-like city. “The demo presented an open world,” recalls Oliver Demangel, who left a position at Ubisoft to take a chance with Gruttola. “You could basically walk around in a city and have some limited interaction with the environment around you.” With the demo in hand and his six-month deadline about to expire, Gruttola started calling every publisher in Europe. Or rather “David Cage” did: realizing that his surname didn’t exactly roll off the tongue, he created the nom-de-plume by appropriating the last name of Johnny Cage, his favorite fighter from Mortal Kombat.

The British publisher Eidos, soaring at the time on the wings of Tomb Raider, invited the freshly rechristened game designer to come out to London. Cage flew back to Paris two days later with a signed development contract in hand. On May 2, 1997, Totem morphed into Quantic Dream, a games rather than a music studio. Over the following month, Cage hired another 35 people to join the five friends he had started out with and help them make Omikron: The Nomad Soul.

Games were entering a new era of mass-market cultural relevance during this period. On the other side of the English Channel, Lara Croft, the heroine of Tomb Raider, had become as much an icon of Cool Britannia as the Spice Girls, giving interviews with journalists and lending her bodacious body to glossy magazine covers, undaunted by her ultimate lack of a corporeal form. Thus when David Cage suggested looking for an established pop act to perhaps lend some music to his game, Eidos was immediately receptive to the idea. The list of possibilities that Cage and his mates provided included such contemporary hipster favorites as Björk, Massive Attack, and Archive. And it also included one name from an earlier generation: David Bowie. Bowie proved the only one to return Eidos’s call. He agreed to come to a meeting in London to hear the pitch.

More than a decade removed from the peak of his commercial success, and still further removed from the unimpeachable, genre-bending run of 1970s albums that will always be the beating heart of his musical legacy, the 1990s version of David Bowie had settled, seemingly comfortably enough, into the role of Britpop’s cool uncle. He went on tour with the likes of Nine Inch Nails and Morrissey and released new albums every other year or so that cautiously incorporated the latest sounds. If the catchy hooks and spark of spontaneity — not to mention the radio play and record sales — weren’t quite there anymore, he did deserve credit for refusing to become a nostalgia act in the way of so many of his peers.

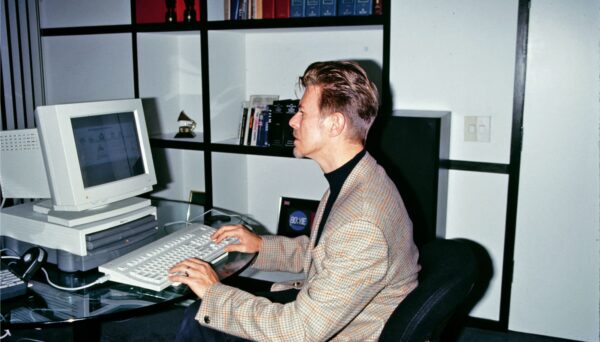

But almost more relevant than Bowie’s current music when it came to Omikron was his deep-seated fascination with the new digital society he saw springing into being around him. He had started to use a computer himself only a few years before: in 1993, when his 22-year-old son Duncan gave him an Apple Macintosh. At first, he used it mostly for playing around with graphics, but he soon found his way onto the Internet for the first time. This digital frontier struck him as a revelation. He became so addicted to surfing the Web that he had to join a support group. He seemed to understand what was coming in a way that few other technologists — never mind rock stars — could match. He became the first prominent musician to make his own website and to use it to engage directly with his fans, the first to debut a new song and its accompanying video on the Internet, the first to co-write a song with a lucky online follower. Displaying a head for business that had always been one of his more underrated qualities, he started charging fans a subscription fee for content at a time when few people other than porn purveyors were bothering to even try to make money online. By the time he took the meeting with Eidos and Quantic Dream, he was in the process of setting up BowieNet, his own Internet service provider. (Yes, really!) He had also just floated his “Bowie Bonds,” by which means his fans could help him to raise the $55 million he needed to buy his back catalog, remaster it, and re-release it as a set of deluxe CDs. From social networking to crowd-sourcing, Bowie was clearly well ahead of the curve. “I don’t even think we’ve seen the tip of the iceberg,” he would say in 2000 in a much-quoted television interview. “I think the potential of what the Internet is going to do, both good and bad, is unimaginable. I think we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.” Subsequent history has resoundingly vindicated him, although perhaps not always in the ways that his inner digital utopianist might have preferred.

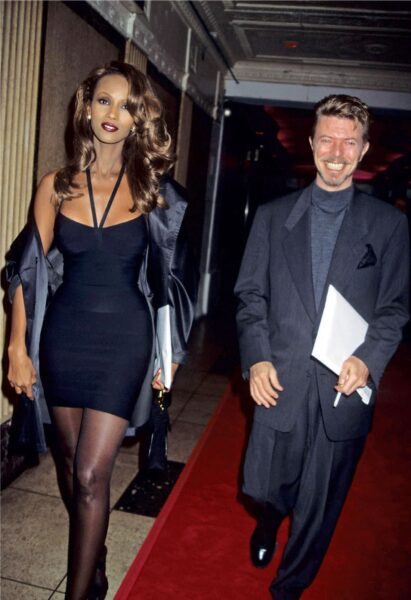

One thing David Bowie was not, however, was a gamer. He took the meeting about Omikron largely at the behest of his son Duncan, who was. He arrived at Eidos’s headquarters accompanied by said son; by his wife, a former supermodel who went by the name of simply Iman; and by his principal musical collaborator of the past decade, the guitarist Reeves Gabrels. They all sat politely but noncommittally while a very nervous group of game developers told them all about Omikron. “Okay, then, what do you need from me?” asked Bowie when the presentation was over. An unusually abashed David Cage said that, at a minimum, they were hoping to license a song or two for the game — maybe the Cold War-era anthem “‘Heroes'” or, failing that, the more recent “Strangers When We Meet.” But in the end, Bowie could be as involved as he wanted to be.

It turned out that he wanted to be quite involved indeed. Over the next couple of hours, Quantic Dream got all they could have dreamed of and then some. Carried away on a wave of enthusiasm, Bowie and Gabrels promised to write and record a whole new album to serve as the soundtrack to the game. And Bowie said he was willing to appear in it personally in motion-captured form. Maybe he and Gabrels could even perform a virtual concert inside the virtual world. Heads were spinning when Bowie and his entourage finally left the building that day.

As promised, Bowie, Iman, and Gabrels came to Paris for a couple of weeks, where they participated in motion-capture and voice-acting sessions and saw and heard more about the world and story of Omikron. Then they went away again; Quantic Dream heard nothing whatsoever from them for months, which made everyone there extremely nervous. But then they popped up again to deliver the finished music — no fewer than ten original songs — right on time, one year almost to the day after they had agreed to the project.

The same tracks were released on September 21, 1999, as hours…, David Bowie’s 23rd studio album. Critics greeted it with some warmth, calling it a welcome return to more conventional songcraft after several albums that had been more electronica than rock. The connection of the music to the not-yet-released game was curiously elided; few reviewers of the album even seemed to realize that it was supposed to be a soundtrack, the first of its type. That same autumn, the veteran progressive-rock group Yes would debut a single original song written for the North American game Homeworld, but Bowie’s contribution to Omikron was on another order of magnitude entirely.

The 1999 David Bowie album hours… was, technically speaking, the soundtrack to Omikron: The Nomad Soul, but you’d have a hard time divining that from looking at it.

Omikron itself appeared about six weeks later. Absolutely no game critic missed the David Bowie connection, which became the lede of every review, thus indicating that the cultural dynamic between games and pop music had perhaps not reached a state of equilibrium just yet. But despite the presence of Bowie, reviews of the game were mixed in Europe, downright harsh in North America. Computer Gaming World got off the best zinger against the game it dubbed Omikrud: “We could be coasters, just for one day.” The magazine went on to explain that “the concept of wrapping an adventure game around a David Bowie album is a cool one. The problem here is with the execution. And your own execution will look more and more desirable, the longer you attempt to play this game.” Rude these words may be, but in my experience they’re the truth.

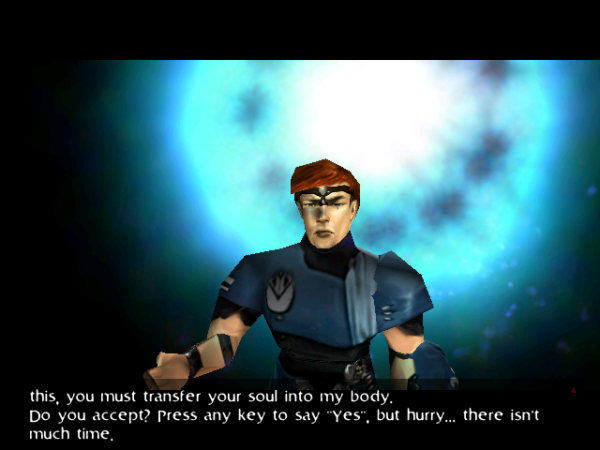

Omikron boasts a striking and memorable opening. When you click the “New Game” button, a fellow dressed in a uniform that looks like a cross between Star Trek and T.J. Hooker pops onto the screen and starts talking directly to you, shattering the fourth wall like so much wet plaster. “My name is Kay’l,” he tells you. (His full name will prove to be Kay’l 669, because of course it is.) “I come from a universe parallel to yours. My world needs your help! You’re the only one who can save us!”

Kay’l wants you to transfer your soul into his body and journey with him back to his home dimension. “You must concentrate!” he hisses. To demonstrate how it’s done, Kay’l holds up his hands and doubles over like a constipated man on a toilet. “You’ve done it!” he then declares with some relief. “Now your soul occupies my body.” (If my soul occupies his body, why am I still sitting in front of my monitor watching him talk at me?) “This is the last time we’ll be able to speak together. Once you’ve crossed the breach, you’ll be on your own. I will take over my body when you leave the game and hold your place until you return.” Thus we learn that Omikron intends to go all-in all the time on diegesis. Lord help us.

You-as-Kay’l emerge in an urban alleyway, only to be set upon by a giant demon that seems as out of place here as you do. This infernal creature is about to make short work of you, thereby revealing a flaw in Kay’l’s master plan. Luckily, a police robot shows up at this juncture and scares away the demon, who apparently isn’t all that after all. “You have been the victim of a violent attack,” RoboCop helpfully informs you, seemingly not noticing that you’re dressed in the uniform of a police officer yourself. “Go home and re-hydrate yourself.”

Trying to take his advice, you fumble about for a while with the idiosyncratic and kind of idiotic controls and interface, and finally manage to locate Kay’l’s apartment. There you discover that he’s married, to a fetching woman whose closet is filled only with hot pants and halter tops. (In time, you will learn that this is true of almost all of the women who live in Omikron.) Seeming unconcerned by the fact that her husband has evidently suffered some sort of psychotic break, disappearing for three days and returning with his memory wiped clean, she lies down on the bed to await your ministrations. You lie down beside her; coitus ensues. Oh, my. Less than half an hour into the game, and you’ve already bonked your poor host’s wife. One wonders whether the fellow is inside his body with you watching the action, so to speak, and, if so, whether he’s beginning to regret fetching you out of the inter-dimensional ether.

Kay’l’s wife will later turn out to be a demon in disguise. I guess that makes it okay to have sex with her under false pretenses. And anyway, these people can do the nasty without having to take their clothes off, just like the characters in a Chris Roberts movie.

I do try to be fair, so let me say now that some things about this game are genuinely impressive. The urban environs qualify at first, especially when you consider that they run in a custom-coded 3D engine. It takes some time for the realization to set in that the city of Omikron is more a carefully curated collection of façades — like a Hollywood soundstage — than a believable community. But once it does, it becomes all too obvious that the people and cars you see aren’t actually going anywhere, even as the overuse of the same models and textures becomes difficult to ignore. There’s exactly one type of car to be seen, for example — and, paying tribute to Henry Ford, it seems to be available in exactly one color. Such infelicities notwithstanding, however, it’s still no mean feat that Quantic Dream pulled off here, a couple of years before Grand Theft Auto III. That you can suspend your disbelief even for a while is an achievement in itself in the context of the times.

Yet this is not a space teeming with interesting interactions and hidden nooks and crannies. With one notable exception, which I’ll get to later, very little that isn’t necessary to the linear main plot is implemented beyond a cursory level. The overarching design is that of a traditional adventure game, not a virtual open world at your beck and call. You learn from Kay’l’s wife — assuming you didn’t figure it out from his uniform — that he is a policeman in this world, on the hunt for a serial killer. (Someone is always a policeman on the hunt for a serial killer in David Cage games.) You have to run down a breadcrumb trail of clues, interviewing suspects and witnesses, collecting evidence, and solving puzzles. The sheer scale of the world is more of a hindrance than a benefit to this type of design, because of the sheer quantity of irrelevancies it throws in your face. By the time you get into the middle stages of the game, it’s becoming really, really hard to figure out where it wants you to go next amidst this generic urban sprawl. And by the same point, your little law-enforcement exercise has become a hunt for demons who are on the verge of destroying the entire multiverse, as you crash headlong into a bout of plot inflation that would shock a denizen of the Weimar Republic. The insane twists and turns the plot leads you through do nothing to help you figure out what the hell the game wants from you.

But I was trying to be kind, wasn’t I? In that spirit, let me note that there are forward-thinking aspects to the design. One of David Cage’s overriding concerns throughout his career has been the elimination of game-over failure states. If you get yourself killed here, the game will always find some excuse to bring you back to life. Unfortunately, the plot engine is littered with soft locks, whereby you can make forward progress impossible by doing or not doing something at the right or wrong moment. I assume that these were inadvertent, but that doesn’t make them any more excusable. This is one of several places where the game breaks an implicit contract it has made with its player. It strongly implies at the outset that you can wing it, that you’re expected to truly inhabit the role of a random Joe Earthling whose (nomad) soul has been sucked into this alternative dimension. But in actuality you have to meta-game like crazy to have a chance.

The save system is a horror, a demonstration of all the ways that the diegetic approach can go wrong. You have to find save points in the world, then use one of a limited supply of “magic rings” you find lying around to access them. In addition to being an affront to busy adults who might not be able to play for an extra half-hour looking for the next save point — precisely the folks whom David Cage says games need to become better at attracting — this system is another great way to soft-lock yourself; use up your supply of magic rings and you’re screwed if you can’t find some more. There is a hint system of sorts built into the game, but it’s accessible only at the save points, and requires you to spend more magic rings to use it. In other words, the player who most needs a hint will be the least likely to have the resources to hand by which to get one. This is another running theme of Omikron: ideas that are progressive and player-friendly in an abstract sense, only to be implemented in a bizarrely regressive, player-hostile way. It bears all the telltale signs of a game that no one ever really tried to play before it was foisted on an unsuspecting public.

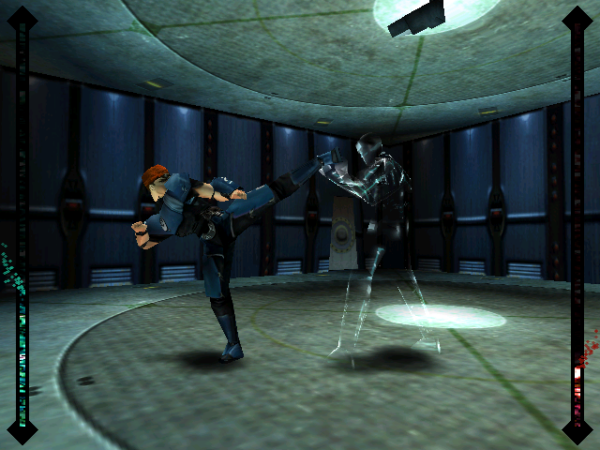

And then there are the places where Omikron suddenly decides to cease being an adventure game and become a beat-em-up, a first-person shooter, or a platformer. I hardly know how to describe just how jarring these transitions are, coming out of the blue with no warning whatsoever. You’ll be in a bar, chatting up the patrons for clues — and bam, you’re in shooter mode. You’ll be searching a locker room — and suddenly you’re playing Mortal Kombat against a dude in tighty-whities. These action modes play as if someone once told the people who made this game about Mortal Kombat and Quake and Tomb Raider, but said people have never actually experienced any of those genres for themselves.

I struggled mightily with the beat-em-up mode at first because I kept trying to play it like a real game of this type — watching my opponent, varying my attacks, trying to establish some sort of rhythm. Then a friend explained to me that you can win every fight just by picking one attack and pounding on that key like a hyperactive monkey, finesse and variety and rhythm be damned.

Alas, the FPS mode is a tougher nut to crack. The default controls are terrible, having nothing in common with any other shooter ever, but you can at least remap them. Sadly, the other problems have no similarly quick fix. Enemies can shoot you when they’re too far away for you to even see them; enemies can spawn out of nowhere right on top of you; your own movements are weirdly jerky, such that it’s hard to aim properly even in the best of circumstances. Just how ineptly is the FPS mode of Omikron implemented, you ask? So ineptly that you can’t even access your health packs during a fight. Again, it’s hard to believe that oversights like this one would have persisted if the developers had ever bothered to ask anyone at all to play their game before they stuck it in a box and shipped it.

The jumping sequences at least take place in the same interface paradigm as the adventure game, but the controls here are just as sloppy, enough to make Omikron the most infuriating platformer since Ultima VIII tarnished a proud legacy. And don’t even get me started on the swimming — your character is inexplicably buoyant, meaning you’re constantly battling to keep his head underwater rather than the opposite — or the excruciating number of times you’ll see the words “I don’t know what to do with that” flash across the screen because you aren’t standing just right in front of the elevator controls or the refrigerator or the vending machine. Even David Cage, a man not overly known for his modesty, confesses that “I wanted to mix different genres, but I wouldn’t say that we were 100-percent successful.” (What percentage successful would you say that you were, David?)

Then we have the writing, the one area where we might have expected Omikron to excel, based on the rhetoric surrounding it. It does not. The core premise, an invasion by demons of a city lifted straight out of Blade Runner, smacks more of adolescent fan fiction than the adult concerns David Cage yearns for games to learn to address. As I already noted, the plot grows steadily more incoherent as it unspools. Interesting, even disturbing elements do churn to the surface with reasonable frequency, but the script is bizarrely oblivious to them. As the game goes on, for instance, you acquire the ability to jump into other bodies than that of poor cuckolded Kay’l. Sometimes you have to sacrifice these bodies — murdering them from the point of view of the souls that call them home — in order to continue the story. The game never acknowledges that this is morally problematic, never so much as feints toward the notion of a greater good or ends justifying the means. This refusal of the game to address the deeper ramifications of its own fiction contributes as much as the half-realized city to giving the whole experience a shallow, plastic feel. Omikron brings up a lot of ideas, but seemingly only because David Cage thinks they sound cool; it has nothing to really say about anything.

Mind you, not having much of anything to say is by no means the kiss of death for a game; I’ve played and loved plenty of games with nothing in particular on their minds. But those games were, you know, fun in other ways. There’s very little fun to be had in Omikron. Everything is dismayingly literal; there isn’t a trace of humor or whimsy or poetry anywhere in the script. I found it to be one of the most oppressive virtual spaces I’ve ever had the misfortune to inhabit.

Among the many insufferable quotes attached to Omikron is the claim by Phil Campbell, a senior designer at Eidos who went on to become creative director at Quantic Dream, that the soul-transfer mechanic makes it “the world’s first Buddhist game.” A true believer who has drunk all the Kool Aid, Campbell thinks Cage is an auteur on par with François Truffaut.

Even the most-discussed aspect of Omikron, at the time of its release and ever since, winds up more confusing than effective. David Cage admits to being surprised by the songs that David Bowie turned up with a year after their first meeting. On the whole, they were sturdy songs if not great ones, unusually revealing and unaffected creations from a man who had made a career of trying on different personas. “I wanted to capture a kind of universal angst felt by many people of my age,” said the 52-year-old singer. The lyrics were full of thoughtful and sometimes disarmingly wise ruminations about growing older and learning to accept one’s place in the world, set in front of the most organic, least computerized backing tracks that Bowie had employed in quite some years. But the songs had little or nothing to do with Cage’s game, in either their lyrics or their sound. Cage claims that Bowie taught him a valuable lesson with his soundtrack: “It’s important that the music doesn’t say the same thing that the imagery does.” A more cynical but possibly more accurate explanation for the discrepancy is that Bowie pretty much forgot about the game and simply made the album he felt like making.

The one place where Omikron’s allegedly open world does reward exploration is the underground concerts you can discover and attend, by a band called the Dreamers who have as their lead singer a de-aged David Bowie. The virtual rock star’s name is a callback to the real star’s distant past: David Jones, the name Bowie was born with. He flounces around the stage like Ziggy Stardust in his prime, dressed in an outfit whose most prominent accessory is a giant furry codpiece. But the actual songs he sings are melancholy meditations on age and time, clearly not the output of a twenty-something glam-rocker. It’s just one more place where Omikron jarringly fails to come together to make a coherent whole, one more way in which it manages to be less than the sum of its parts.

That giant codpiece on young Mr. Jones brings me to one last complaint: this game is positively drenched in cheap, exploitive sex that’s more tacky than titillating. It’s this that turned my dislike for it to downright distaste. Strip clubs and peep shows and advertisements for “biochemical penis implants” abound. Of course, all those absurdly proportioned bodies and pixelated boobies threatening to take your eyes out look ridiculous rather than sexy, as they always do in 3D games from this era. At one point, you have to take over a woman’s body — a body modeled on that of David Bowie’s wife Iman, just to make it extra squicky — and promise sexual favors to a shopkeeper in order to advance the plot. At least you aren’t forced to follow through; thank God for small blessings.

The abject horniness makes Omikron feel more akin to that other kind of entertainment that’s labeled as “adult” — you know, the kind that’s most voraciously consumed by people who aren’t quite adults yet — than it does to the highbrow films to which David Cage has so frequently paid lip service. I won’t accuse Cage of being a skeezy creep; after all, it’s not as if I know the guy. I will only say that, if a skeezy creep was to make a game, I could easily imagine it turning out something like this.

Omikron’s world is the definition of wide rather than deep, but the developers were careful to ensure that you can pee into every single toilet you come across. Make of that what you will.

Once ported to the Sega Dreamcast console in addition to Windows computers, Omikron sold about 400,000 copies in all in Europe, but no more than 50,000 in North America. “It was too arty, too French, too ‘something’ for the American market,” claims David Cage. (I can certainly think of some adjectives to insert there…) Even its European numbers were not good enough to get the direct sequel that Cage initially proposed funded, but were enough, once combined with his undeniable talent for self-marketing, to allow him to continue his career as a would-be gaming auteur. So, we’ll be meeting him again, but not for a few years. We’ll just have to hope that he’s improved his craft by that point.

When I think back on Omikron, I find myself thinking about another French — or rather Francophone Belgian — game as a point of comparison. On the surface, Outcast, which was released the very same year as Omikron, possesses many of the same traits, being another genre-mixing open-world narrative-driven game with a diegetic emphasis that extends as far as the save system; even the name is vaguely similar. I tried it out some months ago at the request of a reader, going into it full of hard-earned skepticism toward what used to be called the “French Touch,” that combination of arty themes and aesthetics with, shall we say, less focus on the details of gameplay. Much to my own shock, I ended up kind of loving it. For the developers of Outcast did sweat those details, did everything they could to make sure their players had a good time instead of just indulging their own masturbatory fantasies about what a game could be. It turns out that some French games are generous, just like some of them from other cultures; others are full of themselves like Omikron.

To be sure, there are people who love this game too, even some who call it their favorite game ever, a cherished piece of semi-outsider interactive art. Far be it from me to tell these people not to feel as they do. Personally, though, I’ve learned to hate this pile of pretentious twaddle with a visceral passion. It’s been years since I’ve seen a game that fails so thoroughly at every single thing it tries to do. For that, Omikron deserves to be nominated as the Worst Game of 1999.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books The Complete David Bowie by Nicholas Pegg, Starman: David Bowie, The Definitive Biography by Paul Trynka, and Bowie: The Illustrated Story by Pat Gilbert. The manual for David Cage’s later game Fahrenheit; PC Zone of November 1999; Computer Gaming World of March 2000; Retro Gamer 153.

Online sources include “David Cage: From the Brink” at MCV, “The Making of Omikron: The Nomad Soul“ at Edge Online, “Omikron Team Interviewed” at GameSpot, “How David Bowie’s Love for the Internet Led Him to Star in a Terrible Dreamcast Game” by Brian Feldman for New York Magazine, “Quantic Dream at 25: David Cage on David Bowie, Controversies, and the Elevation of Story” by Simon Parkin for Games Radar, “The Amazing Stories of a Man You’ve Never Heard of” by Robert Purchese for EuroGamer, “David Cage : « L’attitude de David Bowie m’a profondément marqué »” by William Audureau for Le Monde, “David Bowie’s 1999 Gaming Adventure and Virtual Album” by Richard MacManus for Cybercultural, “Fahrenheit : Interview David Cage / part 1 : L’homme orchestre” by Francois Bliss de la Boissiere for OverGame.com, “Quantic Dream’s David Cage Talks about His Games, His Career, and the PS4: It Allows to ‘Go Even Further'” by Giuseppe Nelva for DualShockers, Quantic Dream’s own version of its history on the studio’s website, and a 2000 David Bowie interview with the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman.

Where to Get It: Omikron: The Nomad Soul is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.

Homeworld

The first-person shooter and the real-time-strategy game, those two genres that had come to absolutely dominate mainstream computer gaming by the end of the 1990s, were surprisingly different in their core technologies. The FPS was all about 3D graphics, as aided and abetted by the new breed of hardware-accelerated 3D cards that seemed to be getting more powerful — and also more expensive — almost by the month. A generation of young men whose fathers might have spent their time tinkering with hot rods in the garage could be found in their studies and bedrooms, trying to outdo their peers by squeezing a little bit more speed and fidelity out of their “rigs”; in this latest era of hot-rodding, frame rate and resolution were the metrics rather than quarter-mile times and dynamometer results.

The technology behind the RTS was fairly traditional by comparison; these games relied on sprites and pixel graphics that weren’t that dissimilar in the broad strokes from the graphics of the 1980s. Running them was less a continuum — less of a question of running a game better or worse — and more a simple binary divide between a computer that could run a given game at an acceptable speed and one that could not. If you happened to be a fan of both dominant genres, as plenty of people were, your snazzy new 3D card had to sit idle when you took a break from Quake or Half-Life to fire up Command & Conquer or Starcraft.

Still, one didn’t have to be much of a tech visionary to see that the unique affordances of 3D graphics could be applied to many other gameplay formulas beyond running around and shooting things from an embodied first-person perspective. The 3D revolution offered a whole slate of temptations to RTS makers and players. Instead of staring down on a battlefield from a fixed isometric view, you could pan around to view it from whatever angle made most sense in the current situation. You could zoom in to micro-manage a skirmish in detail, then zoom out to take in the whole strategic panorama. Embracing the third dimension in graphics promised to bring a whole new dimension of play and spectacle to the RTS. Already in 1997, RTS games like Total Annihilation and Myth: The Fallen Lords were making some use of 3D technology to bring some of those features to the table.

But it wasn’t until Homeworld, a game developed by Relic Entertainment and published by Sierra in late 1999, that an RTS went all-in on 3D, moving the battlefield from the surface of a planet to the infinite depths of space, where up could just as easily be down, or left, or right. Such an experiment was surely inevitable; if these folks hadn’t done it when they did, someone else would have soon enough. What feels far less predestined is how fully-formed this first maximally 3D RTS was, so much so that it would never be comprehensively surpassed in the opinion of some fans of the genre. This is highly unusual in game development, where innovations more typically make their debut complete with plenty of rough edges, which need a few iterations to be sanded down to friction-less perfection. Homeworld, however, was a seemingly immaculate conception, the full package of technology and design right out of the gate. It frustrated the competition by leaving them with so little to improve upon. And it did something else as well, something guaranteed to endear it to me: in an era and a genre in which narrative was widely debased and dismissed, it showed how much a well-presented, intelligent story could do to elevate a game.

The folks from Relic Entertainment who made Homeworld. Alex Garden is at center right, wearing blue jeans and a black pullover.

Most games begin with a gameplay genre: I want to make an FPS, or an RTS, or a CRPG. (Gamers do love to make an alphabet soup out of their hobby, don’t they?) But some games — including many of the most special ones — begin instead with an experience their makers wish to offer their players, then let that dictate the mechanics. It feels appropriate that Homeworld, notwithstanding its status as the canonical first 3D RTS, started the latter way, in the head of a 21-year-old Canadian named Alex Garden in the spring of 1997.

Despite his tender age, Garden thought of himself as a grizzled industry survivor, having been involved with games for five years. He had first been hired as a games tester at Distinctive Software, based right there in his hometown of Vancouver, after he met Distinctive’s founder Don Mattrick in the frozen-yogurt shop where he was working at the time. Half a decade later, he had become a software engineer at Electronic Arts Canada, the new incarnation of Distinctive, working primarily on the Triple Play series of baseball games. But Garden was a young man with big ideas, equipped with a personality big enough to sell them. He was already itching to strike out on his own and try to bring some of them to fruition.