When a novel becomes notably successful, Hollywood generally comes calling to secure the film rights. Many an author naïvely assumes that the acquisition of film rights means an actual film will get made, and in fairly short order at that. And thus is many an author sorely disappointed. Almost every popular novelist who’s been around for a while has stories to tell about Hollywood’s unique form of development purgatory. The sad fact is that the cost of acquiring the rights to even the biggest bestseller is a drop in the bucket in comparison to the cost of making a film out of them. Indeed, the cost is so trivial in terms of Hollywood budgets that many studios are willing to splash out for rights to books they never seriously envision doing anything productive with at all, simply to keep them out of the hands of rivals and protect their own properties in similar genres.

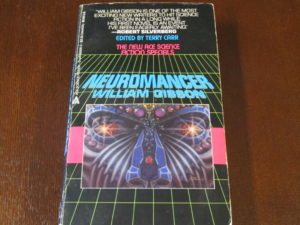

One could well imagine the much-discussed but never-made movie of William Gibson’s landmark cyberpunk novel Neuromancer falling into this standard pattern. Instead, though, its story is far, far more bizarre than the norm — and in its weird way far more entertaining.

Our story begins not with the power brokers of Hollywood, but rather with two young men at the very bottom of the Tinseltown social hierarchy. Ashley Tyler and Jeffrey Kinart were a pair of surfer dudes and cabana boys who worked the swimming pool of the exclusive Beverly Hills Hotel. Serving moguls and stars every day, they noticed that the things they observed their charges doing really didn’t seem all that difficult at all. With a little luck and a little drive, even a couple of service workers like them could probably become players. Despite having no money, no education in filmmaking, and no real inroads with the people who tipped them to deliver poolside drinks, they hatched a plan in early 1985 to make a sequel to their favorite film of all time, the previous year’s strange postmodern action comedy The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension.

The idea was highly problematic, not only for all of the reasons I’ve just listed but also because Buckaroo Banzai, while regarded as something of a cult classic today, had been a notorious flop in its own day, recouping barely a third of its production budget — hardly, in other words, likely sequel fodder. Nevertheless, Tyler and Kinart were able to recruit Earl Mac Rauch, the creator of the Buckaroo Banzai character and writer of the film’s screenplay, to join their little company-in-name-only, which they appropriately titled Cabana Boy Productions. As they made the rounds of the studios, the all-too-plainly clueless Tyler and Kinart didn’t manage to drum up much interest for their Buckaroo Banzai sequel, but the Hollywood establishment found their delusions of grandeur and surfer-boy personalities so intriguing that there was reportedly some talk of signing them to a deal — not to make a Buckaroo Banzai movie, but as the fodder for a television comedy, a sort of Beverly Hillbillies for the 1980s.

After some months, the cabana boys finally recognized that Buckaroo Banzai had little chance of getting resurrected, and moved on to wanting to make a movie out of the hottest novel in science fiction: William Gibson’s Neuromancer. Rauch’s own career wasn’t exactly going gangbusters; in addition to Buckaroo Banzai, he also had on his résumé New York, New York, mob-movie maestro Martin Scorsese’s misbegotten attempt to make a classic Hollywood musical. Thus he agreed to stick with the pair, promising to write the screenplay if they could secure the rights to Neuromancer. In the meantime, they continued to schmooze the guests at the Beverly Hills Hotel, making their revised pitch to any of them who would listen. Against the odds, they stumbled upon one guest who took them very seriously indeed.

As was all too easy to tell from her rictus smile, Deborah Rosenberg was the wife of a plastic surgeon. Her husband, Victor Rosenberg, had been in private practice in New York City since 1970, serving the rich, the famous, and the would-be rich and famous. He also enjoyed a profitable sideline as a writer and commentator on his field for the supermarket tabloids, the glossy beauty magazines, and the bored-housewife talk-show circuit, where he was a regular on programs like Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, The Oprah Winfrey Show, and Donahue. When business took him and his wife to Beverly Hills in late 1985, Deborah was left to loiter by the pool while her husband attended a medical convention. It was there that she made the acquaintance of Tyler and Kinart.

Smelling money, the cabana boys talked up their plans to her with their usual gusto despite her having nothing to do with the film industry. Unaccountably, Deborah Rosenberg thought the idea of making Neuromancer with them a smashing one, and convinced her husband to put up seed capital for the endeavor. Ashley Tyler actually followed the Rosenbergs back to New York and moved into their mansion as a permanent house guest while he and Deborah continued to work on their plans. There would be much speculation around both Hollywood and New York in the months to come about exactly what sort of relationship Deborah and Ashley had, and whether her husband a) was aware of Deborah’s possible extramarital shenanigans and b) cared if he was.

While the irony of Gibson’s book full of cosmetic surgeries and body modifications of all descriptions being adapted by a plastic surgeon would have been particularly rich, Victor took little active role in the project, seeming to regard it (and possibly Ashley?) primarily as a way to keep his high-maintenance wife occupied. He did, however, help her to incorporate Cabana Boy Productions properly in January of 1986, and a few weeks later, having confirmed that Neuromancer rather surprisingly remained un-optioned, offered William Gibson $100,000 for all non-print-media rights to the novel. Gibson was almost as naïve as Deborah and her cabana boys; he had never earned more than the most menial of wages before finishing the science-fiction novel of the decade eighteen months before. He jumped at the offer with no further negotiation whatsoever, mumbling something about using the unexpected windfall to remodel his kitchen. The film rights to the hottest science-fiction novel in recent memory were now in the hands of two California surfer dudes and a plastic surgeon’s trophy wife. And then, just to make the situation that much more surreal, Timothy Leary showed up.

I should briefly introduce Leary for those of you who may not be that familiar with the psychologist whom President Nixon once called “the most dangerous man in America.” At the age of 42 in 1963, the heretofore respectable Leary was fired from his professorship at Harvard, allegedly for skipping lectures but really for administering psychedelic drugs to students without proper authorization. Ousted by the establishment, he joined the nascent counterculture as an elder statesman and cool hippie uncle. Whilst battling unsuccessfully to keep LSD and similar drugs legal — by 1968, they would be outlawed nationwide despite his best efforts — Leary traveled the country delivering “lectures” that came complete with a live backing band, light shows, and more pseudo-mystical mumbo jumbo than could be found anywhere this side of a Scientology convention. In his encounters with the straight mainstream press, he strained to be as outrageous and confrontational as possible. His favorite saying became one of the most enduring of the entire Age of Aquarius: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” Persecuted relentlessly by the establishment as the Judas who had betrayed their trust, Leary was repeatedly arrested for drug possession. This, of course, only endeared him that much more to the counterculture, who regarded each successive bust as another instance of his personal martyrdom for their cause. The Moody Blues wrote an oh-so-sixties anthem about him called “Legend of a Mind” and made it the centerpiece of their 1968 album In Search of the Lost Chord; the Beatles song “Come Together” was begun as a campaign anthem for Leary’s farcical candidacy for governor of California.

In January of 1970, Leary, the last person in the world on whom any judge was inclined to be lenient, was sentenced to ten years imprisonment by the state of California for the possession of two marijuana cigarettes. With the aid of the terrorist group the Weather Underground, he escaped from prison that September and fled overseas, first to Algeria, then to Switzerland, where, now totally out of his depth in the criminal underworld, he wound up being kept under house arrest as a sort of prize pet by a high-living international arms dealer. When he was recaptured by Swiss authorities and extradited back to the United States in 1972, it thus came as something of a relief for him. He continued to write books in prison, but otherwise kept a lower profile as the last embers of the counterculture burned themselves out. His sentence was commuted by California Governor Jerry Brown in 1976, and he was released.

Free at last, he was slightly at loose ends, being widely regarded as a creaky anachronism of a decade that already felt very long ago and far away; in the age of disco, cocaine was the wonderdrug rather than LSD. But in 1983, when he played Infocom’s Suspended, he discovered a new passion that would come to dominate the last thirteen years of his life. He wrote to Mike Berlyn, the author of the game, to tell him that Suspended had “changed his life,” that he had been “completely overwhelmed by the way the characters split reality into six pieces.” He had, he said, “not thought much of computers before then,” but Suspended “had made computers a reality” for him. Later that year, he visited Infocom with an idea for, as one employee of the company remembers it, “a personality that would sit on top of the operating system, observe what you did, and modify what the computer would do and how it would present information based on your personal history, what you’d done on the computer.” If such an idea seems insanely ambitious in the context of early 1980s technology, it perhaps points to some of the issues that would tend to keep Leary, who wasn’t a programmer and had no real technical understanding of how computers worked, at the margins of the industry. His flamboyance and tendency to talk in superlatives made him an uneasy fit with the more low-key personality of Infocom. Another employee remembers Leary as being “too self-centered to make a good partner. He wanted his name and his ideas on something, but he didn’t want us to tell him how to do it.”

His overtures to Infocom having come to naught, Leary moved on, but he didn’t forget about computers. Far from it. As the waves of hype about home computers rolled across the nation, Leary saw in them much the same revolutionary potential he had once seen in peace, love, and LSD — and he also saw in them, one suspects, a new vehicle to bring himself, an inveterate lover of the spotlight, back to a certain cultural relevance. Computers, he declared, were better than drugs: “the language of computers [gives] me the metaphor I was searching for twenty years ago.” He helpfully provided the media with a new go-to slogan to apply to his latest ideas, albeit one that would never quite catch on like the earlier had: “Turn on, boot up, jack in.” “Who controls the pictures on the screen controls the future,” he said, “and computers let people control their own screen.”

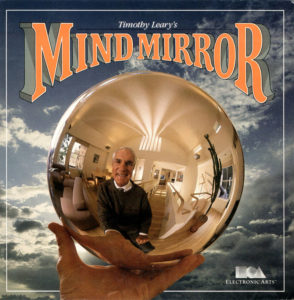

In that spirit, he formed a small software developer of his own, which he dubbed Futique. Futique’s one tangible product was Mind Mirror, published by Electronic Arts in 1986. It stands to this day as the single strangest piece of software Electronic Arts has ever released. Billed as “part tool, part game, and part philosopher on a disk,” Mind Mirror was mostly incomprehensible — a vastly less intuitive Alter Ego with all the campy fun of that game’s terrible writing and dubious psychological insights leached out in favor of charts, graphs, and rambling manifestos. Electronic Arts found that Leary’s cultural cachet with the average computer user wasn’t as great as they might have hoped; despite their plastering his name and picture all over the box, Mind Mirror resoundingly flopped.

It was in the midst of all this activity that Leary encountered William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the oft-cited link between Gibson’s vision of an ecstatic virtual reality called the Matrix and his earlier drug experiences, Leary became an instant cyberpunk convert, embracing the new sub-genre with all of his characteristic enthusiasm. Gibson, he said, had written “the New Testament of the 21st century.” Having evidently decided that the surest route to profundity lay in placing the prefix “cyber-” in front of every possible word, he went on to describe Neuromancer as “an encyclopedic epic for the cyber-screen culture of the immediate future, and an inspiring cyber-theology for the Information Age.” He reached out to the man he had anointed as the cyber-prophet behind this new cyber-theology, sparking up an acquaintance if never quite a real friendship. It was probably through Gibson — the chain of events isn’t entirely clear — that Leary became acquainted with the management of Cabana Boy Productions and their plans for a Neuromancer film. He promptly jumped in with them.

Through happenstance and sheer determination, the cabana boys now had a real corporation with at least a modicum of real funding, the rights to a real bestselling novel, and a real professional screenwriter — and the real Timothy Leary, for whatever that was worth. They were almost starting to look like a credible operation — until, that is, they started to talk.

Cabana Boy’s attempts to sell their proposed $20 million film to Hollywood were, according to one journalist, “a comedy of errors and naïveté — but what they lack in experience they are making up for in showmanship.” Although they were still not taken all that seriously by anyone, their back story and their personalities were enough to secure brief write-ups in People and Us, and David Letterman, always on the lookout for endearing eccentrics to interview and/or make fun of on his late-night talk show, seriously considered having them on. “My bet,” concluded the journalist, “is that they’ll make a movie about Cabana Boy before Neuromancer ever gets off the ground.”

Around the middle of 1986, Cabana Boy made a sizzle reel to shop around the Hollywood studios. William Gibson and his agent and his publicist with Berkley Books were even convinced to show up and offer a few pleasantries. Almost everyone comes across as hopelessly vacuous in this, the only actual film footage Cabana Boy would ever manage to produce.

Shortly after the sizzle reel was made, Earl Mac Rauch split when he was offered the chance to work on a biopic about comedian John Belushi. No problem, said Deborah Rosenberg and Ashley Tyler, we’ll just write the Neuromancer script ourselves — this despite neither of them having ever written anything before, much less the screenplay to a proverbial “major motion picture.” At about the same time, Jeffrey Kinart had a falling-out with his old poolside partner — his absence from the promo video may be a sign of the troubles to come — and left as well. Tyler himself left at the end of 1987, marking the exit of the last actual cabana boy from Cabana Boy, even as Deborah Rosenberg remained no closer to signing the necessary contracts to make the film than she had been at the beginning of the endeavor. On the other hand, she had acquired two entertainment lawyers, a producer, a production designer, a bevy of “financial consultants,” offices in three cities for indeterminate purposes, and millions of dollars in debt. Still undaunted, on August 4, 1988, she registered her completed script, a document it would be fascinating but probably kind of horrifying to read, with the United States Copyright Office.

While all this was going on, Timothy Leary was obsessing over what may very well have been his real motivation for associating himself with Cabana Boy in the first place: turning Neuromancer into a computer game, or, as he preferred to call it, a “mind play” or “performance book.” Cabana Boy had, you’ll remember, picked up all electronic-media rights to the novel in addition to the film rights. Envisioning a Neuromancer game developed for the revolutionary new Commodore Amiga by his own company Futique, the fabulously well-connected Leary assembled a typically star-studded cast of characters to help him make it. It included David Byrne, lead singer of the rock band Talking Heads; Keith Haring, a trendy up-and-coming visual artist; Helmut Newton, a world-famous fashion photographer; Devo, the New Wave rock group; and none other than William Gibson’s personal literary hero William S. Burroughs to adapt the work to the computer.

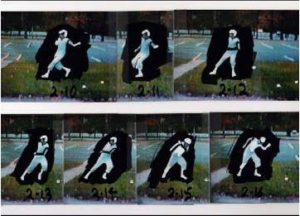

This image created for Timothy Leary’s “mind play” of Neuromancer features David Byrne of the band Talking Heads.

Leary sub-contracted the rights for a Neuromancer game from Cabana Boy, and was able to secure a tentative deal with Electronic Arts. But that fell through when Mind Mirror hit the market and bombed. Another tentative agreement, this time with Jim Levy’s artistically ambitious Activision, collapsed when the much more practical-minded Bruce Davis took over control of that publisher in January of 1987. Neuromancer was a property that should have had huge draw with the computer-game demographic, but everyone, it seemed, was more than a little leery of Leary and his avant-garde aspirations. For some time, the game project didn’t make much more headway than the movie.

Neuromancer the game was saved by a very unusual friendship. While Leary was still associated with Electronic Arts, an unnamed someone at the publisher had introduced him to the head of one of their best development studios, Brian Fargo of Interplay, saying that he thought the two of them “will get along well.” “Timothy and his wife Barbara came down to my office, and sure enough we all hit it off great,” remembers Fargo. “Tim was fascinated by technology; he thought about it and talked about it all the time. So I was his go-to guy for questions about it.”

Being friends with the erstwhile most dangerous man in America was quite an eye-opening experience for the clean-cut former track star. Leary relished his stardom, somewhat faded though its luster may have been by the 1980s, and gloried in the access it gave him to the trendy jet-setting elite. Fargo remembers that Leary “would take me to all the hottest clubs in L.A. I got to go to the Playboy Mansion when I was 24 years old; I met O.J. and Nicole Simpson at his house, and Devo, and David Byrne from Talking Heads. It was a good time.”

His deals with Electronic Arts and Activision having fallen through, it was only natural for Leary to turn at last to his friend Brian Fargo to get his Neuromancer game made. Accepting the project, hot property though Neuromancer was among science-fiction fans, wasn’t without risk for Fargo. Interplay was a commercially-focused developer whose reputation rested largely on their Bard’s Tale series of traditional dungeon-crawling CRPGs; “mind plays” hadn’t exactly been in their bailiwick. Nor did they have a great deal of financial breathing room for artistic experimentation. Interplay, despite the huge success of the first Bard’s Tale game in particular, remained a small, fragile company that could ill-afford an expensive flop. In fact, they were about to embark on a major transition that would only amplify these concerns. Fargo, convinced that the main reason his company wasn’t making more money from The Bard’s Tale and their other games was the lousy 15 percent royalty they were getting from Electronic Arts — a deal which the latter company flatly refused to renegotiate — was moving inexorably toward severing those ties and trying to go it alone as a publisher as well as a developer. Doing so would mean giving up the possibility of making more Bard’s Tale games; that trademark would remain with Electronic Arts. Without that crutch to lean on, an independent Interplay would need to make all-new hits right out of the gate. And, judging from the performance of Mind Mirror, a Timothy Leary mind play didn’t seem all that likely to become one.

Fargo must therefore have breathed a sigh of relief when Leary, perhaps growing tired of this project he’d been flogging for quite some time, perhaps made more willing to trust Fargo’s instincts by the fact that he considered him a friend, said he would be happy to step back into a mere “consulting” role. He did, however, arrange for William Gibson to join Fargo at his house one day to throw out ideas. Gibson was amiable enough, but ultimately just not all that interested, as he tacitly admitted: “I was offered a lot more opportunity for input than I felt capable of acting on. One thing that quickly became apparent to me was that I hadn’t the foggiest notion of the way an interactive computer game had to be constructed, the various levels of architecture involved. It was fascinating, but I felt I’d best keep my nose out of it and let talented professionals go about the actual business of making the game.” So, Fargo and his team, which would come to include programmer Troy A. Miles, artist Charles H.H. Weidman III, and writers and designers Bruce Balfour and Mike Stackpole, were left alone to make their game. While none of them was a William Gibson, much less a William S. Burroughs, they did have a much better idea of what made for a fun, commercially viable computer game than did anyone on the dream team Leary had assembled.

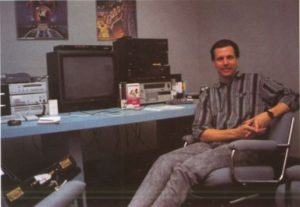

Three fifths of the team that wound up making Interplay’s Neuromancer: Troy Miles, Charles H.H. Weidman III, and Bruce Balfour.

One member of Leary’s old team did agree to stay with the project. Brian Fargo:

My phone rang one night at close to one o’clock in the morning. It was Timothy, and he was all excited that he had gotten Devo to do the soundtrack. I said, “That’s great.” But however I said it, he didn’t think I sounded enthused enough, so he started yelling at me that he had worked so hard on this, and he should get more excitement out of me. Of course, I literally had just woken up.

So, next time I saw him, I said, “Tim, you can’t do that. It’s not fair. You can’t wake me up out of a dead sleep and tell me I’m not excited enough.” He said, “Brian, this is why we’re friends. I really appreciate the fact that you can tell me that. And you’re right.”

But in the end, Devo didn’t provide a full soundtrack, only a chiptunes version of “Some Things Never Change,” a track taken from their latest album Total Devo which plays over Neuromancer‘s splash screen.

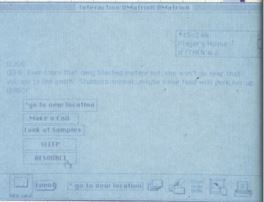

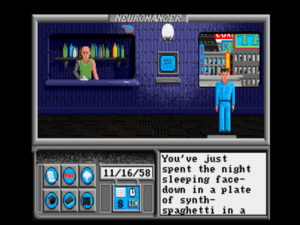

The opening of the game. Case, now recast as a hapless loser, not much better than a space janitor, wakes up face-down in a plate of “synth-spaghetti.”

As an adaptation of the novel, Neuromancer the game can only be considered a dismal failure. Like that of the book, the game’s story begins in a sprawling Japanese metropolis of the future called Chiba City, stars a down-on-his-luck console cowboy named Case, and comes to revolve around a rogue artificial intelligence named Neuromancer. Otherwise, though, the plot of the game has very little resemblance to that of the novel. Considered in any other light than the commercial, the license is completely pointless; this could easily have been a generic cyberpunk adventure.

The game’s tone departs if anything even further from its source material than does its plot. Out of a sense of obligation, it occasionally shoehorns in a few lines of Gibson’s prose, but, rather than even trying to capture the noirish moodiness of the novel, the game aims for considerably lower-hanging fruit. In what was becoming a sort of default setting for adventure-game protagonists by the late 1980s, Case is now a semi-incompetent loser whom the game can feel free to make fun of, inhabiting a science-fiction-comedy universe which has much more to do with Douglas Adams — or, to move the fruit just that much lower, Planetfall or Space Quest — than William Gibson. This approach tended to show up so much in adventure games for very practical reasons: it removed most of the burden from the designers of trying to craft really coherent, believable narratives out of the very limited suite of puzzle and gameplay mechanics at their disposal. Being able to play everything for laughs just made design so much easier. Cop-out though it kind of was, it must be admitted that some of the most beloved classics of the adventure-game genre use exactly this approach. Still, it does have the effect of making Neuromancer the game read almost like a satire of Neuromancer the novel, which can hardly be ideal, at least from the standpoint of the licenser.

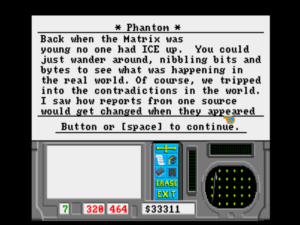

And yet, when divorced of its source material and considered strictly as a computer game Neuromancer succeeds rather brilliantly. It plays on three levels, only the first of which is open to you in the beginning. Those earliest stages confine you to “meat space,” where you walk around, talk with other characters, and solve simple puzzles. Once you find a way to get your console back from the man to whom you pawned it, you’ll be able to enter the second level. Essentially a simulation of the online bulletin-board scene of the game’s own time, it has you logging onto various “databases,” where you can download new programs to run on your console, piece together clues and passwords, read forums and email, and hack banks and other entities. Only around the midway point of the game will you reach the Matrix proper, a true virtual-reality environment. Here you’ll have to engage in graphical combat with ever more potent forms of ICE (“Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics”) to penetrate ever more important databases.

Particularly at this stage, the game has a strong CRPG component; not only do you need to earn money to buy ever better consoles, software, and “skill chips” that conveniently slot right into Case’s brain, but as Case fights ICE on the Matrix his core skills improve with experience. It’s a heady brew, wonderfully varied and entertaining. Despite the limitations of the Commodore 64, the platform on which it made its debut, Neuromancer is one of the most content-rich games of its era, with none of the endless random combats and assorted busywork that stretches the contemporaneous CRPGs of Interplay and others to such interminable lengths. Neuromancer ends just about when you feel it ought to end, having provided the addictive rush of building up a character from a weakling to a powerhouse without ever having bored you in the process.

One of the more eyebrow-raising aspects of Neuromancer is the obvious influence that the real underground world of the Scene had on its. The lingo, the attitudes… all of it is drawn from pirate BBS culture, circa 1988. Ironically, the game evokes the spirit of the Scene far better than it does anything from Gibson’s novel, serving in this respect as a time capsule par excellence. At least some people at Interplay, it seems, were far more familiar with that illegal world than any upstanding citizen ought to have been. Neuromancer is merely one more chapter in the long shared history of legitimate software developers and pirates, who were always more interconnected and even mutually dependent than the strident rhetoric of the Software Publishers Association might lead one to suspect. Richard Garriott’s Akalabeth was first discovered by his eventual publisher California Pacific via a pirated version someone brought into the office; Sid Meier ran one of the most prolific piracy rings in Baltimore before he became one of the most famous game designers in history… the anecdotes are endless. Just to blur the lines that much more, soon after Neuromancer some cracking groups would begin to go legitimate, becoming game makers in their own rights.

Like other Interplay games from this period, Neuromancer is also notable for how far it’s willing to push the barriers of acceptability in what was still the games industry’s equivalent of pre-Hayes Code Hollywood. There’s an online sex board you can visit, a happy-ending massage parlor, a whore wandering the streets. Still, and for all that it’s not exactly a comedic revelation, I find the writing in Neuromancer makes it a more likable game than, say, Wasteland with its somewhat juvenile transgression for transgression’s sake. Neuromancer walks right up to that line on one or two occasions, but never quite crosses it in this critic’s opinion.

Of course, it’s not without some niggles. The interface, especially in the meat-space portions, is a little clunky; it looks like a typical point-and-click adventure game, but its control scheme is less intuitive than it appears, which can lead to some cognitive dissonance when you first start to play. But that sorts itself out once you get into the swing of things. Neuromancer is by far my favorite Interplay game of the 1980s, boldly original but also thoroughly playable — and, it should be noted, rigorously fair. Take careful notes and do your due diligence, and you can feel confident of being able to solve this one.

About to do battle with an artificial intelligence, the most fearsome of the foes you’ll encounter in the Matrix.

Neuromancer was released on the Commodore 64 and the Apple II in late 1988 as one of Interplay’s first two self-published games. The other, fortunately for Interplay but perhaps unfortunately for Neuromancer‘s commercial prospects, was an Amiga game called Battle Chess. Far less conceptually ambitious than Neuromancer, Battle Chess was an everyday chess engine, no better or worse than dozens of other ones that could be found in the public domain, onto which Interplay had grafted “4 MB of animation” and “400 K of digitized sound” (yes, those figures were considered very impressive at the time). When you moved a piece on the board, you got to watch it walk over to its new position, possibly killing other pieces in the process. And that was it, the entire gimmick. But, in those days when games were so frequently purchased as showpieces for one’s graphics and sound hardware, it was more than enough. Battle Chess became just the major hit Interplay needed to establish themselves as a publisher, but in the process it sucked all of Neuromancer‘s oxygen right out of the room. Despite the strength of the license, the latter game went comparatively neglected by Interplay, still a very small company with very limited resources, in the rush to capitalize on the Battle Chess sensation. Neuromancer was ported to MS-DOS and the Apple IIGS in 1989 and to the Amiga in 1990 — in my opinion this last is the definitive version — but was never a big promotional priority and never sold in more than middling numbers. Early talk of a sequel, to have been based on William Gibson’s second novel Count Zero, remained only that. Neuromancer is all but forgotten today, one of the lost gems of its era.

I always make it a special point to highlight games I consider to be genuine classics, the ones that still hold up very well today, and that goes double if they aren’t generally well-remembered. Neuromancer fits into both categories. So, please, feel free to download the Amiga version from right here, pick up an Amiga emulator if you don’t have one already, and have at it. This one really is worth it, folks.

I’ll of course have much more to say about the newly self-sufficient Interplay in future articles. But as for the other players in today’s little drama:

Timothy Leary remained committed to using computers to “express the panoramas of your own brain” right up until he died in 1996, although without ever managing to bring any of his various projects, which increasingly hewed to Matrix-like three-dimensional virtual realities drawn from William Gibson, into anything more than the most experimental of forms.

William Gibson himself… well, I covered him in my last article, didn’t I?

Deborah Rosenberg soldiered on for quite some time alone with the cabana-boy-less Cabana Boy; per contractual stipulation, the Neuromancer game box said that it was “soon to be a major motion picture from Cabana Boy Productions.” And, indeed, she at last managed to sign an actual contract with Tri-Star Pictures on June 2, 1989, to further develop her screenplay, at which point Tri-Star would, “at its discretion,” “produce the movie.” But apparently Tri-Star took discretion to be the better part of valor in the end; nothing else was ever heard of the deal. Cabana Boy was officially dissolved on March 24, 1993. There followed years of litigation between the Rosenbergs and the Internal Revenue Service; it seems the former had illegally deducted all of the money they’d poured into the venture from their tax returns. (It’s largely thanks to the paper trail left behind by the tax-court case, which wasn’t finally settled until 2000, that we know as much about the details of Cabana Boy as we do.) Deborah Rosenberg has presumably gone back to being simply the wife of a plastic surgeon to the stars, whatever that entails, her producing and screenwriting aspirations nipped in the bud and tucked back away wherever it was they came from.

Earl Mac Rauch wrote the screenplay for Wired, the biopic about John Belushi, only to see it greeted with jeers and walk-outs at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival. It went on to become a critical and financial disaster. Having collected three strikes in the form of New York, New York, Buckaroo Banzai, and now Wired, Rauch was out. He vanished into obscurity, although I understand he has resurfaced in recent years to write some Buckaroo Banzai graphic novels.

And as for our two cabana boys, Ashley Tyler and Jeffrey Kinart… who knows? Perhaps they’re patrolling some pool somewhere to this day, regaling the guests with glories that were or glories that may, with the right financial contribution, yet be.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of September 1988; The Games Machine of October 1988; Aboriginal Science Fiction of October 1986; AmigaWorld of May 1988; Compute! of October 1991; The One of February 1989; Starlog of July 1984; Spin of April 1987. Online sources include the sordid details of the Cabana Boy tax case, from the United States Tax Court archive and an Alison Rhonemus’s blog post on some of the contents of Timothy Leary’s papers, which are now held at the New York Public Library. I also made use of the Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Finally, my huge thanks to Brian Fargo for taking time from his busy schedule to discuss his memories of Interplay’s early days with me.)