Although I seem to find myself talking to more and more people in researching this history I’m in the middle of, I don’t often publish the results as straight-up interviews. In fact, I’ve published just one interview in the entire history of this blog, and a very short one at that, done during the early days when I was still finding my way to some extent. I have a number of reasons for avoiding interviews, starting with the fallibility of all human memory and ending with the fact that I consider myself a writer, not a transcriber.

Still, almost any policy ought to have its reasoned exceptions, and this anti-interview policy of mine is itself no exception to that rule. Having just introduced you to AGT and the era of more personal text adventures it ushered in in my last article, it seems appropriate today to let one AGT author tell his own very personal story. So, I’d like to introduce you to Lane Barrow, author of A Dudley Dilemma, the winner of the first of David Malmberg’s eventual six annual AGT competitions. Unique (and uniquely interesting) though it is in so many ways, I trust that some of the more generalized overtones of Lane’s story apply to many of the others who found through AGT a way to make the switch from being text-adventure consumers to text-adventure creators.

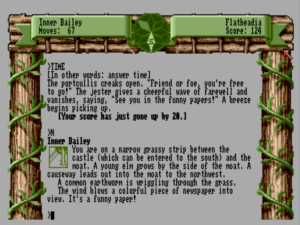

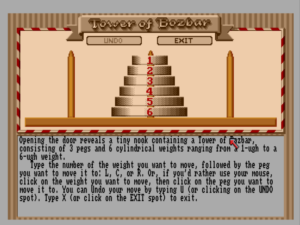

If what follows should tempt you to give A Dudley Dilemma a play — something I highly recommend! — do be sure to go with the “remastered” version Lane has provided, which cleans up the design here and there and works properly with modern interpreters like AGiliTy and Gargoyle. You can download this definitive version from this very site or from the Interactive Fiction Archive.

Thank you so much for talking with me today! Maybe we could start with a bit of your personal background. I believe I read somewhere that you spent some time in the Air Force?

Yes, I was in the Air Force from 1966 to 1970 – two tours in Vietnam. When I rejoined civilian life, I lived in California for all of the 70’s, which was a perfect time to be there (a decade of great music and horrible clothing). I even had a brief encounter with members of the Manson family. Interesting story, but probably not relevant to what you’re looking for.

Sorry, but I can’t just let that one fly by. Please, tell!

It’s not as sinister as it sounds. When I first moved to LA after the Air Force, I hung out with a nascent rock band. We liked to party a lot, and one of the places we frequented belonged to a guy named T.J. and his on-again, off-again girlfriend Jo. I got along really well with T.J. For one thing, he was also a Vietnam vet turned hippy, plus he was creative and outgoing. Turns out he was also an ex-Manson family member. In fact, he was with Manson when Charlie shot some North Hollywood drug dealer. This didn’t sit well with T.J. so he basically left the family soon after.

Anyway, we went over to T.J.’s one night (this was sometime in the summer of 1970) and there were these four girls sitting around the living room with shaved heads and “X”s cut into their foreheads. Apparently these girls were still faithful to Manson and kept a vigil outside the county courthouse while his trial was in session . They had come to see if T.J. could put them up for the night. After a few minutes, T.J. whisked us into the kitchen and suggested that it wasn’t a good idea to party that night, so we left. I still remember the cold stares those girls gave us the whole time we were there. And they never said a single word. So that was my Manson family experience. As I said, living in LA in those days was never boring.

Okay, thanks! So, how did you go from being a Southern California hippie to a Harvard PhD candidate?

I knocked around LA for several years, and then settled in Santa Barbara, where I worked as a baker at Sunrise Bakery (a small co-op enterprise). At the same time, I attended Santa Barbara City College and then UCSB on the GI Bill. I majored in English Lit, and did well enough to get accepted to graduate school at Harvard, also in English.

I was 33 years old when I entered Harvard, so I was a little older than most of my classmates, although there were several other Vietnam vets in the English Dept at the time. I was single then, but I met my future wife there (we’re still together by the way), and her long luxurious hair was the reason I included the sentient hairball in the first part of A Dudley Dilemma.

Bear in mind that my life as a grad student was pretty uneventful compared to Vietnam and California, but that was OK with me. Of course, uneventful isn’t the same thing as stress-free. Grad school can be pretty intense. I actually had more anxiety dreams about the classroom than I ever did about combat. Go figure. Working on the Dudley game was a real stress-reliever for me. It introduced me to programming, which I still enjoy, mostly in Excel these days.

Long before you started to write A Dudley Dilemma, I understand that you discovered text adventures at Harvard?

Yes. In the early ’80s I discovered a couple of fun games on the mainframe while I was learning how to work with computers. These were, of course, Colossal Cave and Zork. If I remember correctly, Zork had just been released commercially, but I didn’t get my first PC until Leading Edge came on the scene in 1985, so the mainframe was my only access. At first, I played both games pretty much equally but Zork slowly took over as my favorite, largely because of its sense of humor.

Why did you come to buy that first PC? Were you intending to use it to play more games like Zork from the beginning?

I’m afraid I had a fairly utilitarian motive for buying my first PC. I was beginning my dissertation at the time, and using the mainframe was a nightmare. If you’ve ever worked with printer “dot commands”, you understand. So I bought a Leading Edge Model D for purely academic work. The computer games were just icing on the cake.

Since I never finished Zork on the mainframe, that was the first game I purchased. I still have the receipt for Zork I tucked into the box ($29.95 purchased on March 31, 1986). Zork II and Zork III were next.

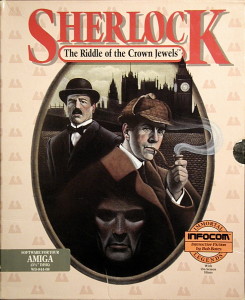

After that, I went on an Infocom binge. I think I bought every title they had at the time, and would wait expectantly for their new releases. I still have many of those boxed sets, complete with tchotchkes. Needless to say, this slowed down my progress on my dissertation…

Did you have any particular favorites among the Infocom catalog?

I liked them all. I gravitated toward the sci-fi / fantasy titles, but I got a big kick out of Bureaucracy also.

Did you play any games from other publishers — whether text adventures or games in other genres — or were you strictly an Infocom guy?

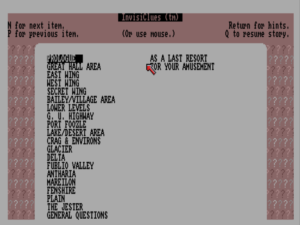

Infocom was pretty much my only focus at first, but eventually I tried other games. However, I don’t remember any specific titles, so obviously they didn’t have the same impact on me as the Infocom offerings. For me, the biggest attraction of the AGT toolkit was its ability to create an Infocom-type game. I had plans to write a second AGT game, but never got around to it. By that time, I was wrapping up grad school and engaged in job-hunting.

I continue to enjoy computer games, post-Infocom, and prefer adventure games, with an emphasis on puzzle-solving. I don’t care much for platform games, or timed puzzles. As you know, that somewhat limits my choices these days, although the Portal games are fun.

How exactly did you become an early AGT adopter? Do you recall how you first learned about the system?

I don’t remember how I learned about AGT, but I was pretty active in various bulletin board chat rooms in those days, so it was probably via one of those. At any rate, I decided to try my hand at creating an Infocom-type game for Dudley House, where I was a resident tutor. I wanted to cram in as many recognizable people, events, places as possible, since the game was going to be on the computer in Dudley House Library. So, I ordered the AGT toolkit, and got to it. I found the language pretty easy to pick up, since it’s very logical. Plus, whenever I had a problem or question, I would email Dave Malmberg, and he would get back to me quickly. I believe I even spoke with him on the phone once or twice, but I might be mis-remembering that (growing old has its advantages, but memory isn’t one of them).

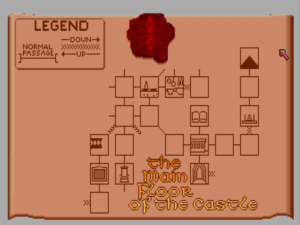

It took me several months to finish the original Dudley Dilemma, and when I put it on the library computer, it caused a bit of a conflict between students who wanted to play the game, and students who wanted to use the on-line card catalog. We even had a competition to see who could finish the game the fastest. I don’t recall the winner’s name, but she was a Junior English major.

I had a ball writing the game, and tried to capture the quirky feel that Infocom was so good at. I ripped off their ideas shamelessly. As you probably noticed, the WHISTLE-CLAP hedge maze sequence is straight out of Leather Goddesses of Phobos (Clap-Hop-Kweepa).

To what extent did you feel yourself to be a part of an AGT community?

If there was an AGT community in those days, I wasn’t aware of it. I did play a couple of other AGT games from time to time (I remember one that had a carnival setting) . If I recall, they were in the overall package that came with the toolkit, or maybe they came later, when Dave mailed out a compilation of AGT contest winners. I don’t remember the chronology all that distinctly.

So, we might even say that you felt yourself to be developing your game largely in a vacuum?

Yes. I really developed Dudley by the seat of my pants, through trial and error. There were times when I was trying to work out a tricky bit of coding that I found myself dreaming about flags and variables. As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to incorporate a lot of actual detail that Dudley students would recognize, so I would jot down notes on a particular incident or individual and then figure out how to code that into the game. Of course I added an exaggerated quality to everything to give it a more whimsical feel, but the vast majority of A Dudley Dilemma is based on reality.

Going back over those days has helped me remember how much fun I had creating the game in the first place. Or maybe nostalgia is a selective process that filters out the “bad.” I’m sure there were probably times when I wondered why I had gotten myself into this project, but obviously I stuck with it.

In general, Dudley is a quite fair game for its day, with few instances of guess-the-verb or read-the-author’s-mind puzzles. There are adventure games that seem designed to frustrate and defeat the player and those that prioritize fun, fair play, and solubility. A Dudley Dilemma is, within the limitations of its era and its technology, very much in the latter category for me. Do you have any comments to make on your general design approach or methodology?

I’m not sure I had a coherent design methodology beyond what I’ve already mentioned: making it accessible to the students of Dudley House. Pretty much all the people and places in the game have their counterparts in the Harvard of the day, and these would have been evident to my core audience. Of course, this dates the game in that respect, but I also tried to make the situations broad enough to have some shelf life, and to be enjoyable even if you didn’t get the “in jokes.” Beyond that, there was a certain random quality to my choices. One thing seemed to flow out of another, maybe just by association of ideas.

You refer to adventure games that frustrate or defeat the player. In the years since I wrote Dudley, I’ve encountered a few of those, and I felt like a bit of the enjoyment was leached out. For example, some of the puzzles in Schizm or The Witness (the recent Jonathan Blow game, not the Infocom title) would challenge Einstein. Infocom games never took that road, which is one of the reasons I like them to this day. They are infused with a focus on fun and entertainment, and that’s what I tried to do in Dudley. However, there IS one overall design element that I’d change if I were re-writing the game today: I would make it impossible to render the game un-winnable.

A few puzzles that might raise some eyebrows today are those relying on outside knowledge. I’m thinking particularly here of the Arabian Nights, Waste Land, and Kingston Trio puzzles. These sorts of “outside research” puzzles were not commonly found in Infocom games (other than puzzles that required information included in the feelies, of course). Any comments on these?

I think I must have been a little ambivalent about those even when I included them. In one of the Dudley re-writes, I added a couple of books in the opening room that, if read, gave the solutions to the Arabian Nights puzzle and to the Waste Land puzzle. I also gave a more detailed hint about the Kingston Trio puzzle, but I don’t recall where that is in the game. Maybe when you first encounter the Kingston Trio album in the giant cockroach maze.

Just a side note: Obviously, the MBTA references have a Boston connection, and since Dudley House was the administrative center for commuting students, a lot of them rode the “T” on a daily basis, so that’s why I added that component. As for the Waste Land bit, this is more obscure. The game opens in Apley Court, which is where T.S. Eliot lived when he was a graduate student at Harvard. Some scholars believe that he began early drafts of The Waste Land at that time, so I couldn’t resist slipping that in.

What audience did you envision playing the game? You said that it was often played on a computer in a library at Harvard. Were you therefore writing primarily for fellow Harvard students? In short, what did you envision doing with the game, as far as distribution, after it was completed, given that you didn’t really feel yourself to be a member of any broader AGT community?

My main audience for the game was always the students of Dudley House, which helped me keep a certain focus to the action. I wanted them to undergo the “shock of recognition” while playing. I didn’t really envision a wider audience, and entering the AGT contest was an afterthought. I was thrilled to win it, which inspired me to “improve” the game over several versions, with pictures, sounds, etc. In retrospect, the original plain vanilla version is still my favorite.

I believe I even thought about applying for a job at Infocom, which was just down the road in Cambridge. That fantasy lasted for about 5 minutes. My only excursions into game design since Dudley are creating some Community Test Chambers in Portal 2. Also fun, but a whole different experience than AGT.

I thought it might be fun — for me and hopefully for you as well as for our readers (especially those who have begun to play the game) — if we could really dig into some of those aspects of daily life at Harvard that inspired so much of Dudley. This is the sort of thing that can make interactive fiction so uniquely personal in contrast to other sorts of games, and that can make amateur efforts like many of the AGT games more interesting in some ways than the slicker, more impersonal games of Infocom. So, I thought we could perhaps play a little game of free association. I’m going to try to jog your memory with various elements of Dudley, and maybe you could respond with their real-life antecedents (if any). Perhaps together we can create a sort of Annotated Dudley Dilemma to go with the Annotated Lurking Horror — the latter was an unusually personal game by Infocom standards — that Janice Eisen and I created earlier. Indeed, it feels particularly appropriate given that The Lurking Horror took place at (a thinly fictionalized) MIT, while A Dudley Dilemma plays out at MIT’s cross-town counterpart Harvard. So…

The scruffy pigeon?

Every adventurer needs a sidekick, right? Of course if I were entirely faithful to that idea, I would have kept the bird nearby for the entire game. Actually, in a later rewrite, I had the pigeon come to the rescue when you face the punk in the mean streets of Cambridge.

The genesis of this character involves an incident in the English Department around Christmas of 1987. One of the senior professors, Barbara Lewalski, was in her office with an advisee, when a soot-covered bird fell into the (unlit) fireplace and started fluttering around the room. Professor Lewalski opened a window and tried to shoo it out to no avail. After a few minutes, the bird fluttered back up the chimney. To make sure the bird was gone, the professor (who was an ample woman) got down on hands and knees to look up the chimney. Right then another senior professor, William Alfred, walked by the office door and did a double-take. According to the advisee, he leaned into the office and said “I don’t believe Santa is due for another week”, and strolled off chuckling. Trust me, Mr. Alfred was one of the only people I ever met who actually chuckled. Obviously this story made the rounds pretty quickly. The original bird wasn’t a pigeon, but since pigeons flock all over Harvard Square and Yard, I had to go with what works. All the rooms in Apley court have fireplaces, which I had already planned to use for roof access. I wanted the player to see early on that the fireplace was also an exit point, so I hoped that the pigeon would help establish that. Once the bird was in the room, I couldn’t resist expanding its role a bit.

The silverfish?

In order to get from the opening site (Apley Court) to the next location (Lehman Hall), you enter the silverfish maze. The maze is actually based on a system of steam tunnels that connect a number of Harvard buildings. Historical note: back in 1968, Harvard security used the steam tunnels to whisk Alabama Governor George Wallace out of Sanders Theater past a large crowd of protesters. That incident was still pretty infamous when I wrote Dudley, so I had to use the steam tunnels somehow. The silverfish guardian evolved out of the large number of those disgusting insects that swarmed around the basement storage area of Apley Court. I just converted the thousands of little ones into one huge one.

The nude tutors on the roof?

Apley Court was originally a residence hall for students (remember T.S. Eliot), but by the time I was there, it only housed the resident tutors for Dudley House. It had a flat roof that was perfect for sunbathing, so we would occasionally sneak up there for that purpose. I say sneak, because technically the roof was off-limits for safety’s sake. To my knowledge, no nude sunbathing ever took place up there, since the building across the street was much taller and afforded an unobstructed view, but I took some poetic license just for comic effect.

The statue in the dining hall?

Ah, Delmar Leighton. He was the first Master of Dudley House and around the time I was writing the game, a large wooden statue of the man was placed in one corner of the dining hall, where it gazed out on the students. I don’t know if the statue was moved from some other location or whether it was commissioned at that time, but it was quite a presence when you were trying to eat. Here’s a picture so you can see what I mean. I concocted the “touch and be touched by all” quote as a gameplay hint, since there’s no such thing on the original.

Mike the guard?

Mike was a real security guard, and I’m really pissed at myself for forgetting his last name. It was something like Moretti or Frascetti. Sigh. Anyway, the real Mike was, if anything, even more diligent and proprietary about his building than my depiction of him. He was the mother hen of Lehman Hall, and I don’t mean that in a negative way. He was chatty and helpful and ever-vigilant. When I was designing the Lehman Hall section, it would have been sacrilege to omit Mike. It took me a while to figure out how to code in Mike’s eventual acceptance of you as a legit student, but using two different ID cards did the trick.

The crazy woman in Harvard Yard?

We called her “The Flapper.” She was rail-thin, about 60 years old or so, and dressed all in black head-to-toe (even in the summer). She mostly wandered around Harvard Square and just inside the gate beside Lehman Hall. She usually had a bag full of scavenged cans and other cast-off stuff, and she was always armed with a little square of folded newspaper that she would “flap” at you if you came too close. I don’t recall if she actually cursed at anyone, so obviously I took some liberties with that. This sequence was my first attempt at creating a random response to player interaction, so I had fun coming up with various curses. As for getting rid of her, I was concerned that the solution might be a bit obscure, (spoilers: highlight to read) but then I reasoned that most of us ignore strange street people anyway, so that part of the game really wrote itself.

Brother Blue in Harvard Yard?

Another real person. He was actually Dr. Hugh Morgan Hill, but his street moniker was Brother Blue, and he was a Boston institution (you can look him up in Wikipedia if you want more detail on his amazing life). When I was there, he would cruise around Harvard Square on roller skates and gather a crowd together so he could tell stories. He referred to himself as a “griot,” a kind of African poet and storyteller. His stories always had an inspirational point to them, but I didn’t think I could do justice to that aspect of his persona, so I made up my own little snippets. I wanted to create the impression of a complete story just by giving the ending. This is another random interaction, so the stories vary depending on the probabilities. I think there are maybe three or four different endings.

The hordes of lawyers?

Not much to say about this. I was looking for a way to “trap” the player with no obvious way out, so I could have done that in any number of ways. Since personal-injury lawyers are always a convenient target, I went for the obvious over-the-top joke. Harvard Law School is just down the walkway from the Science Center, so the internal geography worked out as well.

The professor explaining Hellenic warrior culture to a “class of large young men with no necks?”

Every university, even Harvard (gasp!) has its Easy A or “gut” classes. The class I’m referring to here was officially called Literature & Arts C-14: “The Concept of the Hero in Greek Civilization,” but was universally referred to as “Heroes for Zeros” because of the above-average concentration of jocks. It was taught by Professor Gregory Nagy, who is actually a world-renowned classical scholar. I think it must have come as a shock to many of the students that the class wasn’t as easy as reputation had it. But again, I was going for humor, and I needed a way to introduce a “zero” for later use in the game.

The GreenHouse Grill?

In reality, the Greenhouse Cafe in the Science Center. The Science Center is a massive building with computer rooms (in the 80’s anyway), offices, and classrooms, so having an in-house cafe was a real luxury. It gets the name from a glassed-in atrium section, and it’s a real resting-place, hang-out, meeting spot for students. I don’t recall that it plays a significant role in the game, so I probably included it just for local color and because I used to frequent it myself.

The aging, irate alumnus in the food line?

Well, I think I was channeling my future self when I came up with this guy. Scary! Anyway, the cafe in Dudley House was a tiny little area that served a lot of people every day. It was open to the public, so the students were only a part of the customer base. On any given day, the line at the cash register was clogged at lunch time and tempers would occasionally get frayed. The aging alum was based on a Dudley student’s parents who were visiting him. Things weren’t moving efficiently enough for the father, and he kept muttering about how much better it was when he was a student there. I was behind him in line, so I had to listen to him for many long minutes. That memory stuck with me, so I used it in the game. Trust me, I made the fictional alum a lot more pleasant than the real thing. Helen the cashier is also a real person, and dealt very patiently with the daily chaos.

Paul and Cynthia Hanson?

They were the Co-Masters of Dudley House. Maybe a little explanation is needed here. After their freshman year, the vast majority of Harvard students move into a residential “House” that creates a smaller space within the larger university. These houses have distinct characters, and students tend to form long-lasting loyalties to them. At the time of the game, Dudley House was the center for non-residential or commuter students. Like the residential houses, Dudley had a tutorial staff, dining facilities, lounges, a game room, a library, etc. The houses are overseen by Harvard faculty, often a married couple, called Masters who act “in loco parentis” for the students. House Masters are kind of omnipresent, so I coded them in a way similar to Mike. In other words, they pop up all the time until you figure out how to get rid of them. Talking to them provides a major hint which should be evident after you discover the conundrum dispenser. This machine is obviously based on a different kind of dispenser commonly found in men’s bathrooms of the day. Couldn’t resist the pun!

The Center for High-Energy Metaphysics and their potluck dinner?

Okay, I know I said that Dudley was a non-residential house, but there were a couple of exceptions. About a half-mile or so off campus, near Porter Square, were two old Cambridge Victorians that housed about 15-20 Dudley students between them. These were begun back in the 60’s as commune-type alternatives for students who weren’t attracted to the typical Harvard House experience. One of these houses had a sign at the entrance proclaiming that you were about to enter “The Center for High-Energy Metaphysics,” an obvious pun on experimental physics labs. As a Dudley tutor, I would visit from time to time for potluck dinners, which were largely vegetarian. Seems that the character of those houses hadn’t changed much from the 60’s. Of course, I added the “militant vegetarian” quality just for laughs.

An interesting bit of film trivia here: the Joe Pesci character in the 1994 film With Honors was based on a homeless man who crashed off and on for years at the High-Energy Center. One of the students who lived there at the time wrote the basis of the screenplay. But of course by the time it made it to theaters, the true story was completely unrecognizable.

The party animal?

This character was based on one of my fellow tutors, a mathematician named Yang Wang. Actually, there’s almost no resemblance between them except for the nickname. We used to call Yang a party animal because he so clearly wasn’t. But the location is correct, Yang’s apartment in Peabody Terrace near the Charles River.

The History of Boston Harbor by George Bush?

In the 1988 presidential election between George Bush Sr. and Michael Dukakis, the Bush team hammered Dukakis on how Boston Harbor had turned into a toxic sewage dump under his watch. Since another part of the game involves how polluted the Charles River had become, I threw this in both as a contemporary reference and as an echo of another part of the game. Bostonians used to revel in the bad reputation of the Charles. Maybe you remember the Standell’s song “Love That Dirty Water.” It was a staple between innings at Fenway Park.

The two secretaries, Mrs. J and Mrs. Handy?

These were two of the sweetest people on earth – Louise Janowicz and Margaret Handy. They ran Dudley House on a day-to-day basis and were truly loved by generations of students. Various Masters came and went, but Mrs. J and Mrs Handy kept the place from falling apart. They were the institutional memory and the beating heart of Dudley. There’s no way I could have written the game without including them. The bit of business involving the key to the bathroom is fact-based. Since Dudley House (Lehman Hall) abutted Harvard Square, there were occasions when our men’s room attracted a less than savory element. So in order to gain access, you had to get the key from a hook beside Mrs. J’s desk. And woe is you if you forgot to return it! As I once did.

The queer old dean?

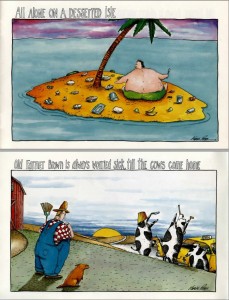

That’s a reference to William Archibald Spooner, Dean of New College, Oxford, and famous for his unintentionally humorous mangling of the English language. As you probably know, the term “spoonerism” refers to him, and “queer old dean” was apparently a reference he once made about “dear old Queen” Victoria. I’ve been a closet fan of puns and spoonerism my whole life, so I had to figure out a way to include him in Dudley. It seemed to me that having his little problem extend beyond the verbal and into the “real” world would be a great way to play around with morphing some of the objects in the game. I confess that I was influenced by Infocom again here (Nord and Bert is full of spoonerisms).

John Marquand?

John Marquand was Senior Tutor at Dudley House during my time there. He was an institution at Dudley and really was a kind of Father Confessor to the undergrads. He was also a bottomless reservoir of knowledge about food and wine, so if you needed advice on a great restaurant, he was your guy. In the game, I actually have him give you a tip about Bartley’s Burgers (another Harvard institution). He is NOT John P. Marquand, the creator of the Mr. Moto detective novels, but they were related. I originally planned to work the Mr. Moto connection in somehow, but that one slipped through the cracks.

Thanks for all that! It really deepens and enriches the game’s “time capsule” quality all these years later.

It was mentioned at the time that A Dudley Dilemma won the competition that you planned to make another game, this one to be based on Charles Dickens, the subject of your dissertation. Whatever became of that idea?

It never really made it out of the concept stage, but my hope was to mingle characters from various novels together in a sort of “through the looking glass” romp. It seemed to me that having, for example, David Copperfield knock some sense into Pip would be satisfying. Or having Scrooge hire Uriah Heep instead of Bob Cratchet would act as a form of karmic justice. I made some notes at the time, but I have no idea where they are today.

Interesting. I’ve often toyed with an idea similar to this one. There’s a long tradition of time-travel text adventures that have you visiting different time periods, using things collected in one time in another to solve puzzles, etc. I’ve often thought to do something similar, but to have you visiting worlds out of literature — an idea partly inspired by Jasper Fforde’s Thursday Next books. Like you, though, I’ve never gotten around to it. The blog sucks up too much time and energy, I’m afraid.

I haven’t read the Fforde books, but I’ll check them out. By the way, if you’re not already familiar with them, you might look for a couple of stories from the 40’s by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, called The Incomplete Enchanter. These have been in and out of print for years, so I expect they’re available somewhere. The protagonist, Harold Shea, is able to enter parallel worlds based on literary works: Norse Edda in one story and Spenser’s Faerie Queene in another. Side note here: when I was studying for my PhD orals, I had to read The Faerie Queene, and I kept looking around the corners of that text for Harold. Sadly, he was nowhere to be found.

Ah, The Faerie Queene… “A gentle knight was pricking on the plain…”

I have a beautiful old Victorian edition that I love to take out and look at. I must confess that I’ve never gotten through the whole thing, though. There’s only so much allegory one man can take I reckon.

I didn’t mind Spenser, but Pilgrim’s Progress did me in. What is it Mrs. Malaprop says – “As headstrong as an allegory on the banks of the Nile.”

Before we wrap up, maybe you could tell just briefly where life took you after the days of Harvard and A Dudley Dilemma.

After I completed Dudley, I dove back into teaching and working on my dissertation, which I never did complete (can’t blame Dudley for this, however). A year or so later, I moved to Connecticut and took a job in the UConn School of Business. My wife was in the English Department at UConn, so this actually allowed us to live under the same roof. In the world of academic marriages, having jobs at the same institution is pretty rare, so we jumped at the chance. I also reasoned that having one English professor in the family was enough, so the transition to business was fairly smooth. Besides, I used to sneak across the Charles to the cafe at the Harvard B-School (the food was really good there), so I must have had a premonition.

My work at the UConn B-School involved corporate consulting and teaching business writing to undergrads and MBA students. Just so we’re clear on this, I taught my students how to write clean English prose, without business jargon. Eventually, I served as MBA Director for 10 years. And yes, there was a certain Dickensian quality to the business school. I’ll leave the interpretation of that remark up to you! I retired from my full-time job in 2012, but I currently work part-time with a UConn program called the EBV (Entrepreneurial Bootcamp for Disabled Veterans). We hold workshops for vets who want to start their own businesses. My contribution is helping them create a business plan.

Thank you! And congratulations on making it to retirement after such an interesting and varied working life. I hope that this article and the “remastered” version of A Dudley Dilemma which we released last week will lead more people to play this very clever game and inadvertent time capsule of life at Harvard in the late 1980s.

Thanks, Jimmy. For my part, this entire exchange has been a real pleasure and has allowed me to relive an enjoyable past experience. Thanks again for putting the final version of the game out there. I thought about doing that myself over the years, but didn’t think there’d be an audience for it.

I continue to read and enjoy your blog, and I’ll probably go back and do it in chronological order to see how it develops over time. I’m sure you’ll be expanding it for many years to come. I hope we can keep in touch, and if I ever decide to follow up with the Dickens game (unlikely), I’ll let you know.

I hope so too! Take care!

Lane Barrow, 2016. He’s a man who likes to sleep with his hat on, which I suppose is better than dying with his boots on.