The last people known to have seen William Colby alive are a cottage caretaker and his sister. They bumped into the former head of the CIA early on the evening of April 27, 1996, watering the willow trees around his vacation home on Neale Sound in Maryland, about 60 miles south of Washington, D.C. The trio chatted together for a few minutes about the fine weather and about the repairs Colby had spent the day doing to his sailboat, which was moored in the marina on Cobb Island, just across the sound. Then the caretaker and his sister went on their way. Everything seemed perfectly normal to them.

The next morning, a local handyman, his wife, and their two children out on the water in their motorboat spotted a bright green canoe washed up against a spit of land that extended from the Maryland shore. The canoe appeared to be abandoned. Moving in to investigate, they found that it was full of sand. This was odd, thought the handyman; he had sailed past this same place the day before without seeing the canoe, and yet so much sand could hardly have collected in it naturally over the course of a single night. It was almost as if someone had deliberately tried to sink the canoe. Oh, well; finders keepers. It really was a nice little boat. He and his family spent several hours shoveling out the sand, then towed the canoe away with them.

In the meantime, Colby’s next-door neighbor was surprised not to see him out and about. The farthest thing from a layabout, the wiry 76-year-old was usually up early, puttering about with something or other around his cottage or out on the sound. Yet now he was nowhere to be seen outside and didn’t answer his door, even though his car was still in the driveway and the neighbor thought she could hear a radio playing inside the little house. Peeking around back, she saw that Colby’s green canoe was gone. At first, she thought the mystery was solved. But as the day wore on and he failed to return, she grew more and more concerned. At 7:00 that evening, she called the police.

When they arrived, the police found that both doors to the cottage were unlocked. The radio was indeed turned on, as was Colby’s computer. Even weirder, a half-eaten meal lay in the sink, surrounded by unwashed dishes and half a glass of white wine. It wasn’t at all like the man not to clean up after himself. And his wallet and keys were also lying there on the table. Why on earth would he go out paddling without them?

Inquiries among the locals soon turned up Colby’s canoe and the story of its discovery. Clearly something was very wrong here. The police ordered a search. Two helicopters, twelve divers, and 100 volunteers in boats pulling drag-lines behind them scoured the area, while CIA agents also arrived to assist the investigation into the disappearance of one of their own; their presence was nothing to be alarmed at, they assured everyone, just standard procedure. Despite the extent of the search effort, it wasn’t until the morning of May 6, nine days after he was last seen, that William Colby’s body was found washed up on the shore, just 130 feet from where the handyman had found his canoe, but on the other side of the same spit of land. It seemed that Colby must have gone canoeing on the lake, then fallen overboard and drowned. He was 76 years old, after all.

But the handyman who had found the canoe, who knew these waters and their currents as well as anyone, didn’t buy this. He was sure that the body could not have gotten so separated from the canoe as to wind up on the opposite side of the spit. And why had it taken it so long to wash up on shore? Someone must have gone out and planted it there later on, he thought. Knowing Colby’s background, and having seen enough spy movies to know what happened to inconvenient witnesses in cases like this one, he and his family left town and went into hiding.

The coroner noticed other oddities. Normally a body that has been in the water a week or more is an ugly, bloated sight. But Colby’s was bizarrely well-preserved, almost as if it had barely spent any time in the water at all. And how could the divers and boaters have missed it for so long, so close to shore as it was?

Nonetheless, the coroner concluded that Colby had probably suffered a “cardiovascular incident” while out in his canoe, fallen into the water, and drowned. This despite the fact that he had had no known heart problems, and was in general in a physical shape that would have made him the envy of many a man 30 years younger than he was. Nor could the coroner explain why he had chosen to go canoeing long after dark, something he was most definitely not wont to do. (It had been dusk already when the caretaker and his sister said goodbye to him, and he had presumably sat down to his dinner after that.) Why had he gone out in such a rush, leaving his dinner half-eaten and his wine half-drunk, leaving his radio and computer still turned on, leaving his keys and wallet lying there on the table? It just didn’t add up in the eyes of the locals and those who had known Colby best.

But that was that. Case closed. The people who lived around the sound couldn’t help but think about the CIA agents lurking around the police station and the morgue, and wonder at everyone’s sudden eagerness to put a bow on the case and be done with it…

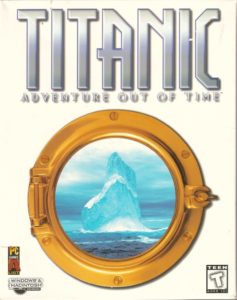

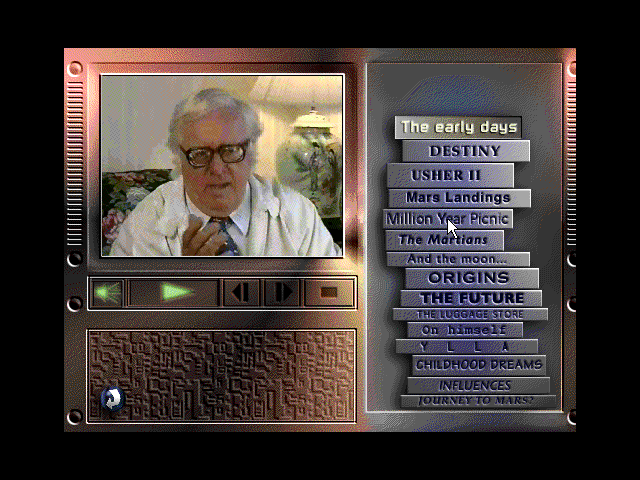

Unusually for a septuagenarian retired agent of the security state, William Colby had also been a game developer, after a fashion at least. In fact, at the time of his death a major game from a major publisher that bore his name very prominently right on the front of the box had just reached store shelves. This article and the next will partly be the story of the making of that game. But they will also be the story of William Colby himself, and of another character who was surprisingly similar to him in many ways despite being his sworn enemy for 55 years — an enemy turned friend who consulted along with him on the game and appeared onscreen in it alongside him. Then, too, they will be an inquiry into some of the important questions the game raises but cannot possibly begin to answer.

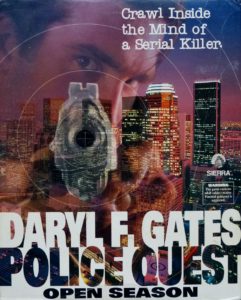

Sierra’s Police Quest: Open Season, created with the help of controversial former Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates, was one of the few finished products to emerge from a brief-lived vision of games as up-to-the-minute, ripped-from-the-headlines affairs. Spycraft: The Great Game was another.

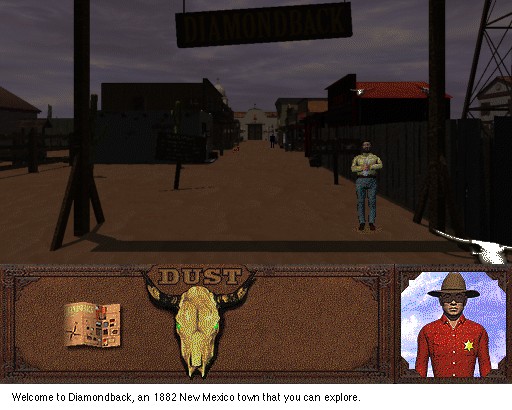

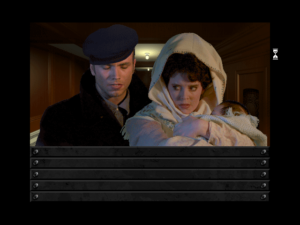

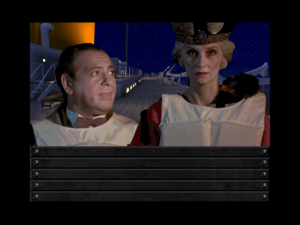

Activision’s Spycraft: The Great Game is the product of a very specific era of computer gaming, when “multimedia” and “interactive movies” were among the buzzwords of the zeitgeist. Most of us who are interested in gaming history today are well aware of the set of technical and aesthetic approaches these terms imply: namely, games built from snippets of captured digitized footage of real actors, with interactivity woven as best the creators can manage between these dauntingly large chunks of static content.

There was a certain ideology that sometimes sprang up in connection with this inclusion of real people in games, a belief that it would allow games to become relevant to the broader culture in a way they never had before, tackling stories, ideas, and controversies that ordinary folks were talking about around their kitchen tables. At the margins, gaming could almost become another form of journalism. Ken Williams, the founder and president of Sierra On-Line, was the most prominent public advocate for this point of view, as exemplified by his decision to make a game with Daryl F. Gates, the chief of police for Los Angeles during the riots that convulsed that city in the spring of 1992. Williams, writing during the summer of 1993, just as the Gates game was being released:

I want to find the top cop, lawyer, airline pilot, fireman, race-car driver, politician, military hero, schoolteacher, white-water rafter, mountain climber, etc., and have them work with us on a simulation of their world. Chief Gates gives us the cop game. We are working with Emerson Fittipaldi to simulate racing, and expect to announce soon that Vincent Bugliosi, the lawyer who locked up Charles Manson, will be working with us to do a courtroom simulation. My goal is that products in the Reality Role-Playing series will be viewed as serious simulations of real-world events, not games. If we do our jobs right, this will be the closest most of us will ever get to seeing the world through these people’s eyes.

It sounded good in theory, but would never get all that far in practice, for a whole host of reasons: a lack of intellectual bandwidth and sufficient diversity of background in the games industry to examine complex social questions in an appropriately multi-faceted way (the jingoistic Gates game is a prime case in point here); a lack of good ideas for turning such abstract themes into rewarding forms of interactivity, especially when forced to work with the canned video snippets that publishers like Sierra deemed an essential part of the overall vision; the expense of the games themselves, the expense of the computers needed to run them, and the technical challenges involved in getting them running, which in combination created a huge barrier to entry for newcomers from outside the traditional gamer demographics; and, last but not least, the fact that those existing gamers who did meet all the prerequisites were generally perfectly happy with more blatantly escapist entertainments, thank you very much. Tellingly, none of the game ideas Ken Williams mentions above ever got made. And I must admit that this failure does not strike me as any great loss for world culture.

That said, Williams, being the head of one of the two biggest American game publishers, had a lot of influence on the smaller ones when he prognosticated on the future of the industry. Among the latter group was Activision, a toppled giant which had been rescued from the dustbin of bankruptcy in 1991 by a young wheeler-dealer named Bobby Kotick. His version of the company got fully back onto its feet the same year that Williams wrote the words above, thanks largely to Return to Zork, a cutting-edge multimedia evocation of the Infocom text adventures of yore, released at the perfect time to capitalize on a generation of gamers’ nostalgia for those bygone days of text and parsers (whilst not actually asking them to read much or to type out their commands, of course).

With that success under their belts, Kotick and his cronies thought about what to do next. Adventure games were hot — Myst, the bestselling adventure of all time, was released at the end of 1993 — and Ken Williams’s ideas about famous-expert-driven “Reality Role-Playing” were in the air. What might they do with that? And whom could they get to help them do it?

They hit upon espionage, a theme that, in contrast to many of those outlined by Williams, seemed to promise a nice balance of ripped-from-the-headlines relevance with interesting gameplay potential. Then, when they went looking for the requisite famous experts, they hit the mother lode with William Colby, the head of the CIA from September of 1973 to January of 1976, and Oleg Kalugin, who had become the youngest general in the history of the First Central Directorate of the Soviet Committee for State Security, better known as the KGB, in 1974.

I’ll return to Spycraft itself in due course. But right now, I’d like to examine the lives of these two men, which parallel one another in some perhaps enlightening ways. Rest assured that in doing so I’m only following the lead of Activision’s marketers; they certainly wanted the public to focus first and foremost on the involvement of Colby and Kalugin in their game.

William Colby (center), looking every inch the dashing war hero in Norway just after the end of World War II.

William Colby was born in St. Paul, Minnesota on January 4, 1920. He was the only child of Elbridge Colby, a former soldier and current university professor who would soon rejoin the army as an officer and spend the next 40 years in the service. His family was deeply Catholic — his father thanks to a spiritual awakening and conversion while a student at university, his mother thanks to long family tradition. The son too absorbed the ethos of a stern but loving God and the necessity of serving Him in ways both heavenly and worldly.

The little family bounced around from place to place, as military families generally do. They wound up in China for three years starting in 1929, where young Bill learned a smattering of Chinese and was exposed for the first time to the often compromised ethics of real-world politics, in this case in the form of the United States’s support for the brutal dictatorship of Chiang Kei-shek. Colby’s biographer Randall Bennett Woods pronounces his time in China “one of the formative influences of his life.” It was, one might say, a sort of preparation for the many ugly but necessary alliances — necessary as Colby would see them, anyway — of the Cold War.

At the age of seventeen, Colby applied to West Point, but was rejected because of poor eyesight. He settled instead for Princeton, a university whose faculty included Albert Einstein among many other prominent thinkers. Colby spent the summer of 1939 holidaying in France, returning home just after the fateful declarations of war in early September, never imagining that the idyllic environs in which he had bicycled and picnicked and practiced his French on the local girls would be occupied by the Nazis well before another year had passed. Back at Princeton, he made the subject of his senior thesis the ways in which France’s weakness had allowed the Nazi threat on its doorstep to grow unchecked. This too was a lesson that would dominate his worldview throughout the decades to come. After graduating, Colby received his officer’s commission in the United States Army, under the looming shadow of a world war that seemed bound to engulf his own country sooner or later.

When war did come on December 7, 1941, he was working as an artillery instructor at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. To his immense frustration, the Army thought he was doing such a good job in that role that it was inclined to leave him there. “I was afraid the war would be over before I got a chance to fight,” he writes in his memoir. He therefore leaped at the opportunity when he saw an advertisement on a bulletin board for volunteers to become parachutists with the 82nd Airborne. He tried to pass the entrance physical by memorizing the eye chart. The doctor wasn’t fooled, but let him in anyway: “I guess your eyesight is good enough for you to see the ground.”

Unfortunately, he broke his ankle in a training jump, and was forced to watch, crestfallen, as his unit shipped out to Europe without him. Then opportunity came calling again, in a chance to join the new Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA. Just as the CIA would later on, the OSS had two primary missions: foreign intelligence gathering and active but covert interference. Colby was to be dropped behind enemy lines, whence he would radio back reports of enemy troop movements and organize resistance among the local population. It would be, needless to say, an astonishingly dangerous undertaking. But that was the way Colby wanted it.

William Colby finally left for Britain in December of 1943, aboard the British luxury liner Queen Elizabeth, now refitted to serve as a troop transport. It was in a London bookstore that he first encountered another formative influence, the book Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence — the legendary Lawrence of Arabia, who had convinced the peoples of the Middle East to rise up against their Turkish overlords during the last world war. Lawrence’s book was, Colby would later say, an invaluable example of “an outsider operat[ing] within the political framework of a foreign people.” It promptly joined the Catholic Bible as one of the two texts Colby carried with him everywhere he went.

As it happened, he had plenty of time for reading: the weeks and then months passed in Britain, and still there came no orders to go into action. There was some talk of using Colby and his fellow American commandos to sow chaos during the run-up to D-Day, but this role was given to British units in the end. Instead Colby watched from the sideline, seething, as the liberation of France began. Then, out of the blue, action orders came at last. On the night of August 14, 1944, Colby and two exiled French soldiers jumped out of a B-24 bomber flying over central France.

The drop was botched; the men landed fifteen miles away from the intended target, finding themselves smack dab in the middle of a French village instead of out in the woods. Luckily, there were no Germans about, and the villagers had no desire to betray them. There followed a hectic, doubtless nerve-wracking month, during which Colby and his friends made contact with the local resistance forces and sent back to the advancing Allied armies valuable information about German troop movements and dispositions. Once friendly armies reached their position, the commandos made their way back to the recently liberated Paris, thence to London. It had been a highly successful mission, with more than enough danger and derring-do to suffice for one lifetime in the eyes of most people. But for Colby it all felt a bit anticlimactic; he had never even discharged his weapon at the enemy. Knowing that his spoken German wasn’t good enough to carry out another such mission behind the rapidly advancing Western European front, Colby requested a transfer to China.

He got another offer instead. Being an accomplished skier, he was asked to lead 35 commandos into the subarctic region of occupied Norway, to interdict the German supply lines there. Naturally, he agreed.

The parachute drop that took place on the night of March 24, 1945, turned into another botched job. Only fifteen of the 35 commandos actually arrived; the other planes strayed far off course in the dark and foggy night, accidentally dropping their passengers over neutral Sweden, or giving up and not dropping them at all. But Colby was among the lucky (?) fifteen who made it to their intended destination. Living off the frigid land, he and his men set about dynamiting railroad tracks and tunnels. This time, he got to do plenty of shooting, as his actions frequently brought him face to face with the Wehrmacht.

On the morning of May 7, word came through on the radio that Adolf Hitler was dead and his government had capitulated; the war in Europe was over. Colby now set about accepting the surrender of the same German occupiers he had recently been harassing. While the operation he had led was perhaps of doubtful necessity in the big picture of a war that Germany had already been well along the path of losing, no one could deny that he had demonstrated enormous bravery and capability. He was awarded the Silver Star.

Gung ho as ever, Colby proposed to his superiors upon returning to London that he lead a similar operation into Francisco Franco’s Spain, to precipitate the downfall of that last bastion of fascism in Europe. Having been refused this request, he returned to the United States, still seeming a bit disappointed that it had all ended so quickly. Here he asked for and was granted a discharge from the Army, asked for and was granted the hand in marriage of his university sweetheart Barbara Heinzen, and asked for and was granted a scholarship to law school. He wrote on his application that he hoped to become a lawyer in the cause of organized labor. (Far from the fire-breathing right-wing extremist some of his later critics would characterize him to be, Colby would vote Democrat throughout his life, maintaining a center-left orientation when it came to domestic politics at least.)

While the war hero William Colby was seemingly settling into a more staid time of life, another boy was growing up in the heart of the nation that Colby and most other Americans would soon come to regard as their latest great enemy. Born on September 6, 1934, in Leningrad (the once and future Saint Petersburg), Oleg Kalugin was, like Colby, an only child of a couple with an ethic of service, the son of a secret-police agent and a former factory worker, both of whose loyalty to communism was unimpeachable; the boy’s grandmother caused much shouting and hand-wringing in the family when she spirited him away to have him baptized in a furtive Orthodox ceremony in a dark basement. That piece of deviancy notwithstanding, Little Oleg was raised to see Joseph Stalin as his god on earth, the one and only savior of his people.

On June 22, 1941, he was “hunting maybugs with a pretty girl,” as he writes, when he saw a formation of airplanes roar overhead and drop a load of bombs not far away. The war had come to his country, six months before it would reach that of William Colby. With the German armies nearing Leningrad, he and his mother fled to the Siberian city of Omsk while his father stayed behind to fight. They returned to a devastated hometown in the spring of 1944. Oleg’s father had survived the terrible siege, but the boy had lost all of his grandparents — including that gentle soul who had caused him to be baptized — along with four uncles to either starvation or enemy bullets.

Kalugin remained a true believer after the Great Patriotic War was over, joining the Young Communist League as soon as he was eligible at the age of fourteen. At seventeen, he decided to join the KGB; it “seemed like the logical place for a person with my academic abilities, language skills, and fervent desire to fight class enemies, capitalist parasites, and social injustice.” Surprisingly, his father, who had seen rather too much of what Soviet-style class struggle really meant over the last couple of decades, tried to dissuade him. But the boy’s mind was made up. He entered Leningrad’s Institute of Foreign Languages, a shallow front for the training of future foreign agents, in 1952.

When Stalin died in March of the following year, the young zealot wrote in his diary that “Stalin isn’t dead. He cannot die. His physical death is just a formality, one that needn’t deprive people of their faith in the future. The fact that Stalin is still alive will be proven by our country’s every new success, both domestically and internationally.” He was therefore shocked when Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, delivered a speech that roundly condemned the country’s erstwhile savior as a megalomaniac and a mass-murderer who had cynically corrupted the ideology of Marx and Lenin to serve his own selfish ends. It was Kalugin’s initiation into the reality that the state he so earnestly served was less than incorruptible and infallible.

Nevertheless, he kept the faith, moving to Moscow for advanced training in 1956. In 1958, he was selected on the basis of his aptitude for English to go to the United States as a graduate student. “Just lay the foundation for future work,” his superiors told him. “Buy yourself good maps. Improve your English. Find out about their way of life. Communicate with people and make as many friends as possible.” Kalugin’s joyous reaction to this assignment reflects the ambivalence with which young Soviets like him viewed the United States. It was, they fervently believed, the epicenter of the imperialism, capitalism, racism, and classism they hated, and must ultimately be destroyed for that reason. Yet it was also the land of jazz and rock and roll, of fast cars and beautiful women, with a standard of living so different from anything they had ever known that it might as well have been Shangri-La. “I daydreamed constantly about America,” Kalugin admits. “The skyscrapers of New York and Chicago, the cowboys of the West…” He couldn’t believe he was being sent there, and on a sort of paid vacation at that, with few concrete instructions other than to experience as much of the American way of life as he could. Even his sadness about leaving behind the nice Russian girl he had recently married couldn’t overwhelm his giddy excitement.

As Oleg Kalugin prepared to leave for the United States, William Colby was about to return to that same country, where he hadn’t been living for seven years. He had become a lawyer as planned and joined the National Labor Relations Board to forward the cause of organized labor, but his tenure there had proved brief. In 1950, he was convinced to join the new CIA, the counterweight to the KGB on the world stage. He loved his new “band of brothers,” filled as he found it to be with “adventuresome spirits who believed fervently that the communist threat had to be met aggressively, innovatively, and courageously.”

In April of 1951, he took his family with him on his first foreign assignment, under the cover identity of a mid-level diplomatic liaison in Stockholm, Sweden. His real purpose was to build and run an intelligence operation there. (All embassies were nests of espionage in those days, as they still are today.) “The perfect operator in such operations is the traditional gray man, so inconspicuous that he can never catch the waiter’s eye in a restaurant,” Colby wrote. He was — or could become — just such a man, belying his dashing commando past. Small wonder that he proved very adept at his job. The type of spying that William Colby did was, like all real-world espionage, more John Le Carré than Ian Fleming, an incrementalist milieu inhabited by just such quiet gray men as him. Dead-letter drops, secret codes, envelopes stuffed with cash, and the subtle art of recruitment without actually using that word — the vast majority of his intelligence contacts would have blanched at the label of “spy,” having all manner of other ways of defining what they did to themselves and others — were now his daily stock in trade.

In the summer of 1953, Colby and his family left Stockholm for Rome. Still riven by discontent and poverty that the Marshall Plan had never quite been able to quell, with a large and popular communist party that promised the people that it alone could make things better, Italy was considered by both the United States and the Soviet Union to be the European country most in danger of changing sides in the Cold War through the ballot box, making this assignment an unusually crucial one. Once again, Colby performed magnificently. Through means fair and occasionally slightly foul, he propped up Italy’s Christian Democratic Party, the one most friendly to American interests. His wife and five young children would remember these years as their happiest time together, with the Colosseum visible outside their snug little apartment’s windows, with the trapping of their Catholic faith all around them. The sons became altar boys, learning to say Mass in flawless Latin, and Barbara amazed guests with her voluble Italian, which was even better than her husband’s.

She and her children would gladly have stayed in Rome forever, but after five years there her husband was growing restless. The communist threat in Italy had largely dissipated by now, thanks to an improving economy that made free markets seem more of a promise than a threat, and Colby was itching to continue the shadowy struggle elsewhere. In 1958, he was recalled to the States to begin preparing for a new, more exotic assignment: to the tortured Southeast Asian country of Vietnam, which had recently won its independence from France, only to become a battleground between the Western-friendly government of Ngo Dinh Diem and a communist insurgency led by Ho Chi Minh.

While Colby was hitting the books at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, in preparation for his latest assignment, Kalugin was doing the same as a philology student on a Fulbright scholarship to New York City’s Columbia University. (Fully half of the eighteen exchange students who traveled with him were also spies-in-training.) A natural charmer, he had no trouble ingratiating himself with the native residents of the Big Apple as he had been ordered to do.

He went home when his one-year scholarship expired, but returned to New York City one year after that, to work as a journalist for Radio Moscow. Now, however, his superiors expected a bit more from him. Despite the wife and young daughter he had left behind, he seduced a string of women who he believed could become valuable informants — so much so that American counter-espionage agents, who were highly suspicious of him, labeled him a “womanizer” and chalked it up as his most obvious weakness, should they ever be in need of one to exploit. (For his part, Kalugin writes that “I always told my officers, male and female, ‘Don’t be afraid of sex.’ If they found themselves in a situation where making love with a foreigner could help our work, I advised them to hop into bed.”)

Kalugin’s unlikely career as Radio Moscow’s foreign correspondent in New York City lasted almost four years in all. He covered — with a pro-Soviet spin, naturally — the election of President John F. Kennedy, the trauma of the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the assassination of Kennedy by a man with Soviet ties. He was finally called home in early 1964, his superiors having decided he was now attracting too much scrutiny from the Americans. He found returning to the dingy streets of Moscow from the Technicolor excitement of New York City to be rather dispiriting. “Worshiping communism from afar was one thing. Living in it was another thing altogether,” he writes wryly, echoing sentiments shared by many an idealistic Western defector for the cause. Shortly after his return, the reform-minded Nikita Khrushchev was ousted in favor of Leonid Brezhnev, a man who looked as tired as the rest of the Soviet Union was beginning to feel. It was hard to remain committed to the communist cause in such an environment as this, but Kalugin continued to do his best.

William Colby, looking rather incongruous in his typical shoe salesman’s outfit in a Vietnamese jungle.

William Colby might have been feeling similar sentiments somewhere behind that chiseled granite façade of his. For he was up to his eyebrows in the quagmire that was Vietnam, the place where all of the world’s idealism seemed to go to die.

When he had arrived in the capital of Saigon in 1959, with his family in tow as usual, he had wanted to treat this job just as he had his previous foreign postings, to work quietly behind the scenes to support another basically friendly foreign government with a communist problem. But Southeast Asia was not Europe, as he learned to his regret — even if the Diem family were Catholic and talked among themselves in French. There were systems of hierarchy and patronage inside the leader’s palace that baffled Colby at every turn. Diem himself was aloof, isolated from the people he ruled, while Ho Chi Minh, who already controlled the northern half of the country completely and had designs on the rest of it, had enormous populist appeal. The type of espionage Colby had practiced in Sweden and Italy — all mimeographed documents and furtive meetings in the backs of anonymous cafés — would have been useless against such a guerilla insurgency even if it had been possible. Which it was not: the peasants fighting for and against the communists were mostly illiterate.

Colby’s thinking gradually evolved, to encompass the creation of a counter-insurgency force that could play the same game as the communists. His mission in the country became less an exercise in pure espionage and overt and covert influencing than one in paramilitary operations. He and his family left Vietnam for Langley in the summer of 1962, but the country was still to fill a huge portion of Colby’s time; he was leaving to become the head of all of the CIA’s Far Eastern operations, and there was no hotter spot in that hot spot of the world than Vietnam. Before departing, the entire Colby family had dinner with President Diem in his palace, whose continental cuisine, delicate furnishings, and manicured gardens almost could lead one to believe one was on the French Riviera rather than in a jungle in Southeast Asia. “We sat there with the president,” remembers Barbara. “There was really not much political talk. Yet there was a feeling that things were not going well in that country.”

Sixteen months later — in fact, just twenty days before President Kennedy was assassinated — Diem was murdered by the perpetrators of a military coup that had gone off with the tacit support of the Americans, who had grown tired of his ineffectual government and felt a change was needed. Colby was not involved in that decision, which came down directly from the Kennedy White House to its ambassador in the country. But, good soldier that he was, he accepted it after it had become a fait accompli. He even agreed to travel to Vietnam in the immediate aftermath, to meet with the Vietnamese generals who had perpetrated the coup and assure them that they had powerful friends in Washington. Did he realize in his Catholic heart of hearts that his nation had forever lost the moral high ground in Vietnam on the day of Diem’s murder? We cannot say.

The situation escalated quickly under the new President Lyndon Johnson, as more and more American troops were sent to fight a civil war on behalf of the South Vietnamese, a war which the latter didn’t seem overly inclined to fight for themselves. Colby hardly saw his family now, spending months at a stretch in the country. Lawrence of Arabia’s prescription for winning over a native population through ethical persuasion and cultural sensitivity was proving unexpectedly difficult to carry out in Vietnam, most of whose people seemed just to want the Americans to go away. It appeared that a stronger prescription was needed.

Determined to put down the Viet Cong — communist partisans in the south of the country who swarmed over the countryside, killing American soldiers and poisoning their relations with the locals — Colby introduced a “Phoenix Program” to eliminate them. It became without a doubt the biggest of all the moral stains on his career. The program’s rules of engagement were not pretty to begin with, allowing for the extra-judicial execution of anyone believed to be in the Viet Cong leadership in any case where arresting him was too “hard.” But it got entirely out of control in practice, as described by James S. Olsen and Randy W. Roberts in their history of the war: “The South Vietnamese implemented the program aggressively, but it was soon laced with corruption and political infighting. Some South Vietnamese politicians identified political enemies as Viet Cong and sent Phoenix hit men after them. The pressure to identify Viet Cong led to a quota system that incorrectly labeled many innocent people the enemy.” Despite these self-evident problems, the Americans kept the program going for years, saying that its benefits were worth the collateral damage. Olsen and Roberts estimate that at least 20,000 people lost their lives as a direct result of Colby’s Phoenix Program. A large proportion of them — possibly even a majority — were not really communist sympathizers at all.

In July of 1971, Colby was hauled before the House Committee on Government Operations by two prominent Phoenix critics, Ogden Reid and Pete McCloskey (both Republicans.) It is difficult to absolve him of guilt for the program’s worst abuses on the basis of his circuitous, lawyerly answers to their straightforward questions.

Reid: Can you state categorically that Phoenix has never perpetrated the premeditated killing of a civilian in a noncombat situation?

Colby: No, I could not say that, but I do not think it happens often. Individual members of it, subordinate people in it, may have done it. But as a program, it is not designed to do that.

McCloskey: Did Phoenix personnel resort to torture?

Colby: There were incidents, and they were treated as an unjustifiable offense. If you want to get bad intelligence, you use bad interrogation methods. If you want to get good intelligence, you had better use good interrogation methods.

Oleg Kalugin (right) receives from Bulgarian security minister Dimitri Stoyanov the Order of the Red Star, thanks largely to his handling of John Walker. The bespectacled man standing between and behind the two is Yuri Andropov, then the head of the KGB, who would later become the fifth supreme leader of the Soviet Union.

During the second half of the 1960s, Oleg Kalugin spent far more time in the United States than did William Colby. He returned to the nation that had begun to feel like more of a home than his own in July of 1965. This time, however, he went to Washington, D.C., instead of New York City. His new cover was that of a press officer for the Soviet Foreign Ministry; his real job was that of a deputy director in the KGB’s Washington operation. He was to be a spy in the enemy’s city of secrets. “By all means, don’t treat it as a desk job,” he was told.

Kalugin took the advice to heart. He had long since developed a nose for those who could be persuaded to share their country’s deepest secrets with him, long since recognized that the willingness to do so usually stemmed from weakness rather than strength. Like a lion on the hunt, he had learned to spot the weakest prey — the nursers of grudges and harborers of regrets; the sexually, socially, or professionally frustrated — and isolate them from the pack of their peers for one-on-one persuasion. At one point, he came upon a secret CIA document that purported to explain the psychology of those who chose to spy for that yin to his own service’s yang. He found it to be so “uncannily accurate” a description of the people he himself recruited that he squirreled it away in his private files, and quoted from it in his memoir decades later.

Acts of betrayal, whether in the form of espionage or defection, are almost in every case committed by morally or psychologically unsteady people. Normal, psychologically stable people — connected with their country by close ethnic, national, cultural, social, and family ties — cannot take such a step. This simple principle is confirmed by our experience of Soviet defectors. All of them were single. In every case, they had a serious vice or weakness: alcoholism, deep depression, psychopathy of various types. These factors were in most cases decisive in making traitors out of them. It would only be a slight exaggeration to say that no [CIA] operative can consider himself an expert in Soviet affairs if he hasn’t had the horrible experience of holding a Soviet friend’s head over the sink as he poured out the contents of his stomach after a five-day drinking bout.

What follows from that is that our efforts must mostly be directed against weak, unsteady members of Soviet communities. Among normal people, we should pay special attention to the middle-aged. People that age are starting their descent from their psychological peak. They are no longer children, and they suddenly feel the acute realization that their life is passing, that their ambitions and youthful dreams have not come true in full or even in part. At this age comes the breaking point of a man’s career, when he faces the gloomy prospect of pending retirement and old age. The “stormy forties” are of great interest to an [intelligence] operative.

It’s great to be good, but it’s even better to be lucky. John Walker, the spy who made Kalugin’s career, shows the truth in this dictum. He was that rarest of all agents in the espionage trade: a walk-in. A Navy officer based in Norfolk, Virginia, he drove into Washington one day in late 1967 with a folder full of top-secret code ciphers on the seat of his car next to him, looked up the address of the Soviet embassy in the directory attached to a pay phone, strode through the front door, plunked his folder down on the front desk, and said matter-of-factly, “I want to see the security officer, or someone connected with intelligence. I’m a naval officer. I’d like to make some money, and I’ll give you some genuine stuff in return.” Walker was hastily handed a down payment, ushered out of the embassy, and told never under any circumstances to darken its doors again. He would be contacted in other ways if his information checked out.

Kalugin was fortunate enough to be ordered to vet the man. The picture he filled in was sordid, but it passed muster. Thirty years old when his career as a spy began, Walker had originally joined the Navy to escape being jailed for four burglaries he committed as a teenager. A born reprobate, he had once tried to convince his wife to become a prostitute in order to pay off the gambling debts he had racked up. Yet he could also be garrulous and charming, and had managed to thoroughly conceal his real self from his Navy superiors. A fitness report written in 1972, after he had already been selling his country’s secrets for almost five years, calls him “intensely loyal, taking great pride in himself and the naval service, fiercely supporting its principles and traditions. He possesses a fine sense of personal honor and integrity, coupled with a great sense of humor.” Although he was only a warrant officer in rank, he sat on the communications desk at Norfolk, handling radio traffic with submarines deployed all over the world. It was hard to imagine a more perfect posting for a spy. And this spy required no counseling, needed no one to pretend to be his friend, to talk him down from crises of conscience, or to justify himself to himself. Suffering from no delusions as to who and what he was, all he required was cold, hard cash. A loathsome human being, he was a spy handler’s dream.

Kalugin was Walker’s primary handler for two years, during which he raked in a wealth of almost unbelievably valuable information without ever meeting the man face to face. Walker was the sort of asset who turns up “once in a lifetime,” in the words of Kalugin himself. He became the most important of all the spies on the Kremlin’s payroll, even recruiting several of his family members and colleagues to join his ring. “K Mart has better security than the Navy,” he laughed. He would continue his work long after Kalugin’s time in Washington was through. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Navy personnel wondered at how the Soviets always seemed to know where their ships and submarines were and where their latest exercises were planned to take place. Not until 1985 was Walker finally arrested. In a bit of poetic justice, the person who turned him in to the FBI was his wife, whom he had been physically and sexually abusing for almost 30 years.

The luster which this monster shed on Kalugin led to the awarding of the prestigious Order of the Red Star, and then, in 1974, his promotion to the rank of KGB general while still just shy of his 40th birthday, making him the youngest such in the post-World War II history of the service. By that time, he was back in Moscow again, having been recalled in January of 1970, once again because it was becoming common knowledge among the Americans that his primary work in their country was that of a spy. He was too hot now to be given any more long-term foreign postings. Instead he worked out of KGB headquarters in Moscow, dealing with strategic questions and occasionally jetting off to far-flung trouble spots to be the service’s eyes and ears on the ground. “I can honestly say that I loved my work,” he writes in his memoir. “My job was always challenging, placing me at the heart of the Cold War competition between the Soviet Union and the United States.” As ideology faded, the struggle against imperialism had become more of an intellectual fascination — an intriguing game of chess — than a grand moral crusade.

William Colby too was now back in his home country on a more permanent basis, having been promoted to executive director of the CIA — the third highest position on the agency’s totem pole — in July of 1971. Yet he was suffering through what must surely have been the most personally stressful period of his life since he had dodged Nazis as a young man behind enemy lines.

In April of 1973, his 23-year-old daughter Catherine died of anorexia. Her mental illness was complicated, as they always are, but many in the family believed it to have been aggravated by being the daughter of the architect of the Phoenix Program, a man who was in the eyes of much of her hippie generation Evil Incarnate. His marriage was now, in the opinion of his biographer Randall Bennett Woods, no more than a “shell.” Barbara blamed him not only for what he had done in Vietnam but for failing to be there with his family when his daughter needed him most, for forever skipping out on them with convenient excuses about duty and service on his lips.

Barely a month after Catherine’s death, Colby got a call from Alexander Haig, chief of staff in Richard Nixon’s White House: “The president wants you to take over as director of the CIA.” It ought to have been the apex of his professional life, but somehow it didn’t seem that way under current conditions. At the time, the slow-burning Watergate scandal was roiling the CIA almost more than the White House. Because all five of the men who had been arrested attempting to break into the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters the previous year had connections to the CIA, much of the press was convinced it had all been an agency plot. Meanwhile accusations about the Phoenix Program and other CIA activities, in Vietnam and elsewhere, were also flying thick and fast. The CIA seemed to many in Congress to be an agency out of control, ripe only for dismantling. And of course Colby was still processing the loss of his daughter amidst it all. It was a thankless promotion if ever there was one. Nevertheless, he accepted it.

Colby would later claim that he knew nothing of the CIA’s many truly dirty secrets before stepping into the top job. These were the ones that other insiders referred to as the “family jewels”: its many bungled attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro, before and after he became the leader of Cuba, as well as various other sovereign foreign leaders; the coups it had instigated against lawfully elected foreign governments; its experiments with mind control and psychedelic drugs on unwilling and unwitting human subjects; its unlawful wiretapping and surveillance of scores of Americans; its longstanding practice of opening mail passing between the United States and less-than-friendly nations. That Colby could have risen so high in the agency without knowing these secrets and many more seems dubious on the face of it, but it is just possible; the CIA was very compartmentalized, and Colby had the reputation of being a bit of a legal stickler, just the type who might raise awkward objections to such delicate necessities. “Colby never became a member of the CIA’s inner club of mandarins,” claims the agency’s historian Harold Ford. But whether he knew about the family jewels or not beforehand, he was stuck with them now.

Perhaps in the hope that he could make the agency’s persecutors go away if he threw them just a little red meat, Colby came clean about some of the dodgy surveillance programs. But that only whet the public’s appetite for more revelations. For as the Watergate scandal gradually engulfed the White House and finally brought down the president, as it became clear that the United States had invested more than $120 billion and almost 60,000 young American lives into South Vietnam only to see it go communist anyway, the public’s attitude toward institutions like the CIA was not positive; a 1975 poll placed the CIA’s approval rating at 14 percent. President Gerald Ford, the disgraced Nixon’s un-elected replacement, was weak and unable to protect the agency. Indeed, a commission chaired by none other than Vice President Nelson Rockefeller laid bare many of the family jewels, holding back only the most egregious incidents of meddling in foreign governments. But even those began to come out in time. Both major political parties had their sights set on future elections, and thus had a strong motivation to blame a rogue CIA for any and all abuses by previous administrations. (Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, for example, had personally ordered and supervised some of the attempts on Fidel Castro’s life during the early 1960s.)

It was a no-win situation for William Colby. He was called up to testify in Congress again and again, to answer questions in the mold of “When did you stop beating your wife?”, as he put it to colleagues afterward. Everybody seemed to hate him: right-wing hardliners because they thought he was giving away the store (“It is an act of insanity and national humiliation,” said Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, “to have a law prohibiting the president from ordering assassinations”), left-wingers and centrists because they were sure he was hiding everything he could get away with and confessing only to that which was doomed to come out anyway — which was probably true. Colby was preternaturally cool and unflappable at every single hearing, which somehow only made everyone dislike him that much more. Some of his few remaining friends wanted to say that his relative transparency was a product of Catholic guilt — over the Phoenix Program, over the death of his daughter, perchance over all of the CIA’s many sins — but it was hard to square that notion with the rigidly composed, lawyerly presence that spoke in clipped, minimalist phrases before the television cameras. He seemed more like a cold fish than a repentant soul.

On November 1, 1975 — exactly six months after Saigon had fallen, marking the humiliating final defeat of South Vietnam at the hands of the communists — William Colby was called into the White House by President Ford and fired. “There goes 25 years just like that,” he told Barbara when he came home in a rare display of bitterness. His replacement was George Herbert Walker Bush, an up-and-coming Republican politician who knew nothing about intelligence work. President Ford said such an outsider was the only viable choice, given the high crimes and misdemeanors with which all of the rank and file of the CIA were tarred. And who knows? Maybe he was right. Colby stayed on for three more months while his green replacement got up to speed, then left public service forever.

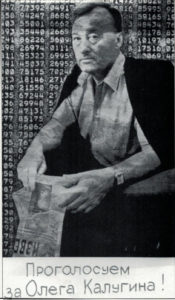

An Oleg Kalugin campaign poster from 1990, after he reinvented himself as a politician. “Let’s vote for Oleg Kalugin!” reads the caption.

Oleg Kalugin was about to suffer his own fall from grace. According to his account, his rising star flamed out when he ventured out on a limb to support a defector from the United States, one of his own first contacts as a spy handler, who was now accused of stealing secrets for the West. The alleged double agent was sent to a Siberian prison despite Kalugin’s advocacy. Suspected now of being a CIA mole himself, Kalugin was reassigned in January of 1980 to a dead-end job as deputy director of the KGB’s Leningrad branch, where he would be sure not to see too much valuable intelligence. You live by the sword, you die by the sword; duplicity begets suspicions of duplicity, such that spies always end up eating their own if they stay in the business long enough.

Again according to Kalugin himself, it was in Leningrad that his nagging doubts about the ethics and efficacy of the Soviet system — the same ones that had been whispering at the back of his mind since the early 1960s — rose to a roar which he could no longer ignore. “It was all an elaborately choreographed farce, and in my seven years in Leningrad I came to see that we had created not only the most extensive totalitarian state apparatus in history but also the most arcane,” he writes. “Indeed, the mind boggled that in the course of seven decades our communist leaders had managed to construct this absurd, stupendous, arcane ziggurat, this terrifyingly centralized machine, this religion that sought to control all aspects of life in our vast country.” We might justifiably wonder that it took him so long to realize this, and note with some cynicism that his decision to reject the system he had served all his life came only after that system had already rejected him. He even confesses that, when Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982 and was replaced by Yuri Andropov, a former head of the KGB who had always thought highly of Kalugin, he wasn’t above dreaming of a return to the heart of the action in the intelligence service. But it wasn’t to be. Andropov soon died, to be replaced by another tired old man named Konstantin Chernenko who died even more quickly, and then Mikhail Gorbachev came along to accidentally dismantle the Soviet Union in the name of saving it.

In January of 1987, Kalugin was given an even more dead-end job, as a security officer in the Academy of Sciences in Moscow. From here, he watched the extraordinary events of 1989, as country after country in the Soviet sphere rejected its communist government, until finally the Berlin Wall fell, taking the Iron Curtain down with it. Just like that, the Cold War was over, with the Soviet Union the undeniable loser. Kalugin must surely have regarded this development with mixed feelings, given what a loyal partisan he had once been for the losing side. Nevertheless, on February 26, 1990, he retired from the KGB. After picking up his severance check, he walked a few blocks to the Institute of History and Archives, where a group of democracy activists had set up shop. “I want to help the democratic movement,” he told them, in a matter-of-fact tone uncannily similar to that of John Walker in a Soviet embassy 22 years earlier. “I am sure that my knowledge and experience will be useful. You can use me in any capacity.”

And so Oleg Kalugin reinvented himself as an advocate for Russian democracy. A staunch supporter of Boris Yeltsin and his post-Soviet vision for Russia, he became an outspoken opponent of the KGB, which still harbored in its ranks many who wished to return the country to its old ways. He was elected to the Supreme Soviet in September of 1990, in the first wave of free and fair elections ever held in Russia. When some of his old KGB colleagues attempted a coup in August of 1991, he was out there manning the barricades for democracy. The coup was put down — just.

William Colby in his later years, enjoying his sailboat, one of his few sources of uncalculated joy.

William Colby too had to reinvent himself after the agency he served declared that it no longer needed him. He wrote a circumspect, slightly anodyne memoir about his career; its title of Honorable Men alone was enough to tell the world that it wasn’t the tell-all book from an angry spy spurned that it might have been hoping for. He consulted for the government on various issues for larger sums than he had ever earned as a regular federal employee, appeared from time to time as an expert commentator on television, and wrote occasional opinion pieces for the national press, most commonly about the ongoing dangers posed by nuclear weapons and the need for arms-control agreements with the Soviet Union.

In 1982, at the age of 62, this stiff-backed avatar of moral rectitude fell in love with a pretty, vivacious 37-year-old, a former American ambassador to Grenada named Sally Shelton. It struck those who knew him as almost a cliché of a mid-life crisis, of the sort that the intelligence services had been exploiting for decades — but then, clichés are clichés for a reason, aren’t they? “I thought Bill Colby had all the charisma of a shoe clerk,” said one family friend. “Sally is a very outgoing woman, even flamboyant. She found him a sex object, and with her he was.” The following year, Colby asked his wife Barbara for a divorce. She was taken aback, even if their marriage hadn’t been a particularly warm one in many years. “People like us don’t get a divorce!” she exclaimed — meaning, of course, upstanding Catholic couples of the Greatest Generation who were fast approaching their 40th wedding anniversary. But there it was. Whatever else was going on behind that granite façade, it seemed that Colby felt he still had some living to do.

None of Colby’s family attended the marriage ceremony, or had much to do with him thereafter. He lost not only his family but his faith: Sally Shelton had no truck with Catholicism, and he only went to church after he married her for weddings and funerals. Was the gain worth the loss? Only Colby knew the answer.

Old frenemies: Oleg Kalugin and William Colby flank Ken Berris, who directed the Spycraft video sequences.

Oleg Kalugin met William Colby for the first time in May of 1991, when both were attending the same seminar in Berlin — appropriately enough, on the subject of international terrorism, the threat destined to steal the attention of the CIA and the Russian FSB (the successor to the KGB) as the Cold War faded into history. The two men had dinner together, then agreed to be jointly interviewed on German television, a living symbol of bygones becoming bygones. “What do you think of Mr. Colby as a leading former figure in U.S. intelligence?” Kalugin was asked.

“Had I had a choice in my earlier life, I would have gladly worked under Mr. Colby,” he answered. The two became friends, meeting up whenever their paths happened to cross in the world.

And why shouldn’t they be friends? They had led similar lives in so many ways. Both were ambitious men who had justified their ambition as a call to service, then devoted their lives to it, swallowing any moral pangs they might have felt in the process, until the people they served had rejected them. In many ways, they had more in common with one another than with the wives and children they had barely seen for long stretches of their lives.

And how are we to judge these two odd, distant men, both so adept at the art of concealment as to seem hopelessly impenetrable? “I am not emotional,” Colby said to a reporter during his turbulent, controversy-plagued tenure as director of the CIA. “I admit it. Oh, don’t watch me like that. You’re looking for something underneath which isn’t there. It’s all here on the surface, believe me.”

Our first instinct might be to scoff at such a claim; surely everyone has an inner life, a tender core they dare reveal only to those they love best. But maybe we should take Colby at his word; maybe doing so helps to explain some things. As Colby and Kalugin spouted their high-minded ideals about duty and country, they forgot those closest to them, the ones who needed them most of all, apparently believing that they possessed some undefined special qualities of character or a special calling that exempted them from all that. Journalist Neil Sheehan once said of Colby that “he would have been perfect as a soldier of Christ in the Jesuit order.” There is something noble but also something horrible about such devotion to an abstract cause. One has to wonder whether it is a crutch, a compensation for some piece of a personality that is missing.

Certainly there was an ultimate venality, an amorality to these two men’s line of work, as captured in the subtitle of the computer game they came together to make: “The Great Game.” Was it all really just a game to them? It would seem so, at least at the end. How else could Kalugin blithely state that he would have “gladly” worked with Colby, forgetting the vast gulf of ideology that lay between them? Tragically, the ante in their great game was all too often human lives. Looking back on all they did, giving all due credit to their courage and capability, it seems clear to me that the world would have been better off without their meddling. The institutions they served were full of people like them, people who thought they knew best, who thought they were that much cleverer than the rest of the world and had a right to steer its course from the shadows. Alas, they weren’t clever enough to see how foolish and destructive their arrogance was.

“My father lived in a world of secrets,” says William’s eldest son Carl Colby. “Always watching, listening, his eye on the door. He was tougher, smarter, smoother, and could be crueler than anybody I ever knew. I’m not sure he ever loved anyone, and I never heard him say anything heartfelt.” Was William Colby made that way by the organization he served, or did he join the organization because he already was that way? It’s impossible to say. Yet we must be sure to keep these things in mind when we turn in earnest to the game on which Colby and Kalugin allowed their names to be stamped, and find out what it has to say about the ethical wages of being a spy.

(Sources: the books Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, Lost Crusader: The Secret Wars of CIA Director William Colby by John Prados, Spymaster: My Thirty-Two Years in Intelligence and Espionage against the West by Oleg Kalugin, Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam, 1945-2010, sixth edition by James S. Olson and Randy Roberts, Shadow Warrior: William Egan Colby and the CIA by Randall B. Woods, Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA by William Colby and Peter Forbath, and Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America’s Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam by William Colby and James McCargar; the documentary film The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby; Sierra On-Line’s newsletter InterAction of Summer 1993; Questbusters of February 1994. Online sources include “Who Murdered the CIA Chief?” by Zalin Grant at Pythia Press.)