Michael Davis has created an original game based on my recent series of articles on Trinity. To say too much more about it would be to spoil it, so I’ll just tell you that it’s well worth a play — if perhaps not quite in the way you might expect. My thanks to Michael!

The 68000 Wars, Part 2: Jack Is Back!

In letting the March 31, 1984, deadline slip away without signing a licensing agreement with Atari, David Morse was taking a crazy risk. If he couldn’t find some way of scraping together $500,000 plus interest to repay Atari’s loan, Atari could walk away with the Amiga chipset for nothing, and Amiga would almost certainly go bust. All activity at Amiga therefore centered on getting the Lorraine ready for the Summer Consumer Electronic Show in Chicago, scheduled to begin on June 3. Summer CES was to be Amiga’s Hail Mary, their last chance to interest somebody — anybody — in what they had to offer enough to plunk down over half a million dollars just for openers, just to keep Atari from making the whole point moot.

By the time Summer CES arrived the Lorraine was a much more refined contraption than the one they had shown at Winter CES back in January, if still a long, long way from being a finished computer. Jay Miner’s custom chips had now been miniaturized and stamped into silicon, improving the machine’s reliability as much as it reduced its size. The Lorraine’s longstanding identity crisis was also now largely a thing of the past, the videogame crash and the example of the Macintosh having convinced everyone that what it ultimately needed to be was a computer, not a game console. Programmers like Carl Sassenrath, Dale Luck, and R.J. Mical had thus already started work on a proper operating system. Amiga’s computer was planned to be capable of doing everything the Mac could, but in spectacular color and with multitasking. That dream was, however, still a long way from fruition; the Lorraine could still be controlled only via a connected Sage IV workstation.

Led by software head Bob Pariseau as master of ceremonies, Amiga put on the best show they possibly could inside their invitation-only booth at Summer CES. The speech-synthesis library the software folks had put together was a big crowd-pleaser; spectators delighted in shouting out off-the-cuff phrases for the Lorraine to repeat, in either a male or female voice. But their hands-down favorite once again proved to be Boing, now dramatically enhanced: the ball now bounced side to side instead of just up and down, and a dramatic coup de grâce had been added in the form of sampled booms that moved from speaker to speaker to create a realistic soundscape. This impressive demonstration of Paula’s stereo-sound capabilities leaked beyond the confines of Amiga’s closed booth and out onto the crowded show floor, causing attendees to look around in alarm for the source of the noise.

Whatever the merits of their new-and-improved dog-and-pony show, Amiga also improved their credibility enormously by demonstrating that their chipset could work as actual computer chips and, indeed, simply by having survived and returned to CES once again. A bevy of industry heavyweights traipsed through Amiga’s booth that June: Sony, Hewlett Packard, Philips, Silicon Graphics, Apple. (Steve Jobs, ever the minimalist, allegedly scoffed at the Lorraine as over-engineered, containing too much fancy hardware for its own good.) The quantity and quality of Amiga’s write-ups in the trade press also increased significantly. Compute!, the biggest general-interest computing magazine in the country, raved that the Lorraine was “possibly the most advanced personal computer ever,” “the beginning of a completely new generation,” and “enough to make an IBM PC look like a four-function calculator.” Still, Amiga left the show without the thing they needed most: a viable alternative to Atari. With just a few weeks to go, their future looked grim. And then Commodore called.

To understand the reasons behind that phone call, we have to return to January 13, 1984, the day of that mysterious board meeting at Commodore that outraged their CEO Jack Tramiel so egregiously as to send him storming out of the building and burning rubber out of the parking lot, never to return. In his noncommittal statements to the press immediately after the divorce was made official, Tramiel said he planned to take some time to consider his next move. For now, he and his wife were going to spend a year traveling the world, to make up for all the vacations they had skipped over the course of his long career.

At the time that he said it, he seems to have meant it. He and wife Helen made it as far as Sri Lanka by April. But by that point he’d already had all he could take of the life of leisure. He and Helen returned to the United States so Jack could start a new venture to be called simply Tramel Technology. (The spelling of the name was changed to reflect the proper pronunciation of Tramiel’s last name; most Americans’ habit of mispronouncing the last syllable had always driven him crazy.) His plan was to scrape together funding and a team and build the mass-market successor to the Commodore 64. In the process, he hoped to stick it to Commodore and especially to its chairman, with whom he had always had a — to put it mildly — fraught relationship. Business had always been war to Tramiel, but now this war was personal.

To get Tramel Technology off the ground, he needed people, and almost all of the people he knew and had confidence in still worked at Commodore. Tramiel therefore started blatantly poaching his old favorites. That April and May at Commodore were marked by a mass exodus, as suddenly seemingly every other employee was quitting, all headed to the same place. Jack’s son Sam was the first; many felt it was likely Jack’s desire to turn Commodore into the Tramiel family business that had precipitated his departure in the first place. Then Tony Takai, the mastermind of Commodore’s Japanese branch; John Feagans, who was supposed to be finishing up the built-in software for Commodore’s new Plus/4 computer; Neil Harris, programmer of many of the most popular VIC-20 games; Ira Velinsky, a production designer; Lloyd “Red” Taylor, a president of technology; Bernie Witter, a vice president of finance; Sam Chin, a manager of finance; Joe Spiteri and David Carlone, manufacturing experts; Gregg Pratt, a vice president of operations. The most devastating defectors of all were Commodore’s head of engineering Shiraz Shivji and three of his key hardware engineers: Arthur Morgan, John Heonig, and Douglas Renn.

The mass exodus amounted to a humiliating vote of no-confidence in Irving Gould’s hand-picked successor to Tramiel, a former steel executive named Marshall Smith who was as bland as his name. The loss of engineering talent in particular left Commodore, who had already been in a difficult situation, even worse off. As Commodore’s big new machine for 1984, the Plus/4, amply demonstrated, there just wasn’t a whole lot left to be done with the 8-bit technology that had gotten Commodore this far. Trouble was, their engineers had experience with very little else. Tramiel had always kept Commodore’s engineering staff to the bare minimum, a fact which largely explains why they had nothing compelling in the pipeline now beyond the underwhelming Plus/4 and its even less impressive little brother the Commodore 16. And now, having lost four more key people… well, the situation didn’t look good.

And that was what made Amiga so attractive. At first Commodore, like Atari before them, envisioned simply licensing the Amiga chipset, in the process quite probably — again like Atari — using Amiga’s position of weakness to extort from them a ridiculously good deal. But within days of opening negotiations their thinking began to change. Here was not only a fantastic chipset but an equally fantastic group of software and hardware engineers, intimately familiar with exactly the sort of next-generation 16-bit technology with which Commodore’s own remaining engineers were so conspicuously unacquainted. Why not buy Amiga outright?

On June 29, David Morse walked unexpectedly into the lobby of Atari’s headquarters and requested to see his primary point of contact there, one John Farrand. Farrand already had an inkling that something was up; Morse had been dodging his calls and finding excuses to avoid face-to-face meetings for the last two weeks. Still, he wasn’t prepared for what happened next. Morse told him that he was here to pay back the $500,000, plus interest, and sever their business relationship. He then proceeded to practically shove a check into the hands of a very confused and, soon, very irate John Farrand. Two minutes later he was gone.

The check had of course come from Commodore, given as a gesture of good faith in their negotiations with Amiga and, more practically, to keep Atari from walking away with the technology they’d now decided they’d very much like to have for themselves. Six weeks later negotiations between Commodore and Amiga ended with the purchase by the former of the latter for $27 million. David Morse had his miracle. His investors and employees got a nice payday in return for their faith. And, most importantly, his brilliant young team would get the chance to turn Miner’s chipset into a real computer all their own, designed — for the most part — their way.

It’s worth dwelling for just a moment here on the sheer audacity of the feat Morse had just pulled off. Backed against the wall by an Atari that smelled blood in the water, he had taken their money, used it to finish the chipset and the Lorraine well enough to get him a deal with their arch-rival, then paid Atari back and walked away. It all added up to a long con worthy of The Sting. No wonder Atari, who had gotten as far as starting to design the motherboard for the game console destined to house the chipset, was pissed. And yet the Atari that would soon seek its revenge would not be the same Atari as the one he had negotiated with in March. Confused yet? To understand we must, once again, backtrack just slightly.

Atari may have been a relative Goliath in contrast to Amiga’s David in early 1984, but that’s not to say that they were financially healthy. Far from it. The previous year had been a disastrous one, marked by losses of over half a billion thanks to the Great Videogame Crash. CEO Ray Kassar had left under a cloud of accusations of insider trading, mismanagement, and general incompetence; no one turns faster on a wonder boy than Wall Street. Now his successor, a once and future cigarette mogul named James Morgan, was struggling to staunch the bleeding by laying off employees and closing offices almost by the week. Parent company Warner Communications, figuring that the videogame bubble was well and truly burst, just wanted to be rid of Atari as quickly and painlessly as possible.

Jack Tramiel, meanwhile, was becoming a regular presence in Silicon Valley, looking for facilities and technologies he could buy to get Tramel Technology off the ground. In fact, he was one of the many who visited Amiga during this period, although negotiations didn’t get very far. Then one day in June he got a call from a Warner executive, asking if he’d be interested in taking Atari off their hands.

A deal was reached in remarkably little time. Tramiel would buy not the company Atari itself but the assets of its home-computer and game-console divisions; he had no interest in its other branch, standup arcade games. Said assets included property, trademarks and copyrights, equipment, product inventories, and, not least, employees. He would pay, astonishingly, nothing upfront for it all, instead agreeing to $240 million in long-term notes and giving Warner a 32 percent stake in Tramel Technology. Warner literally sold the company — or, perhaps better said, gave away the company — out from under Morgan, who was talking new products and turnaround plans one day and arrived the next to be told to clear out his executive suite to make room for Tramiel. On July 1, just two days after Morse had given back that $500,000, the biggest chunk of Atari, a company which just a couple of years before had been the fastest growing in the history of American business, became the possession of tiny Tramel Technology, which was still being run at the time out of a vacant apartment in a dodgy neighborhood. Within days Tramiel renamed Tramel Technology to Atari Corporation. For years to come there would be two Ataris: Tramiel’s Atari Corporation, maker of home computers and game consoles, and Atari Games, maker of standup arcade games. It would take quite some time to disentangle the two; even the headquarters building would be shared for some time to come.

Legal trouble between Commodore and Jack Tramiel’s new Atari started immediately. Commodore fired the first salvo, suing Shiraz Shivji and his fellow engineers. When they had decamped to join Tramiel, Commodore claimed, they had taken with them a whole raft of technical documents under the guise of “personal goods.” A court injunction issued at Commodore’s request effectively barred them from doing any work at all for Tramiel, paralyzing his plans to start working on a new computer for several weeks. Shivji and company eventually returned a set of backup tapes taken from Commodore engineering’s in-house central server, full of schematics and other documents. Perhaps tellingly in light of the computer they would soon begin to build, many of the documents related to the Commodore 900, a prototyped but never manufactured Unix workstation to be built around the 16-bit Zilog Z8000 CPU.

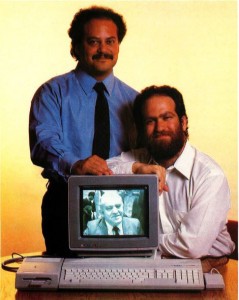

Sam and Leonard Tramiel, who would play a larger and larger role in the running of Atari as time went on.

If Tramiel was looking for a way to get revenge, he was soon to find what looked like a pretty good opportunity. Whilst going through files of documents in early August, Jack’s son Leonard discovered the Amiga agreement, complete with the $500,000 cashed check from Atari to Amiga, and brought it to his father’s attention. Jack Tramiel, who had long made a practice of treating the courts as merely another field of battle in keeping with his “business is war” philosophy, thought they just might have something. But it wasn’t immediately obvious to whom the cancelled contract should belong: to Atari Games (i.e., the coin-op people), to Warner, or to his own new Atari Corporation. Some hasty negotiating secured him clear title; Warner didn’t seem to know anything about the old agreement or what it might have meant for Atari’s future had it gone off according to plan. On August 13, as Commodore and Amiga were signing the contracts and putting the bow on the Amiga acquisition and as Shivji’s engineers were starting up work again on what was now to be the next-generation Atari computer, Atari filed suit against Amiga and against David Morse personally in Santa Clara Superior Court, alleging contract fraud. In their first motion they sought a legal injunction while the case was resolved that would have stopped the work of Commodore’s newly minted Amiga division in its tracks, and for a much longer period of time than Commodore’s more straightforward suit against Shivji and company.

Thankfully for Commodore, they didn’t get the injunction. However, the legal battle thus sparked would drag on for more than two-and-a-half years. In early 1985 Atari expanded their suit dramatically, adding Commodore, who had of course been footing the legal bill for Amiga and Morse’s defense anyway, as co-defendants — alleging them in effect to have been co-conspirators with Morse and Amiga in the fraud. They also added on a bunch of patent claims, one very important one in particular relating back to a patent Atari held on the old Atari 400 and 800 designs that Jay Miner had been responsible for in the late 1970s; those designs did indeed share a lot of attributes with the chipset he had developed at Amiga. For this sin Miner personally was added to the suit as yet another co-defendant. The whole thing was finally wrapped up only in March of 1987, in a sealed settlement whose full details have never come to light. Scuttlebutt of then and now, though, would have it that Commodore came out on the losing end, forced to pay Atari’s legal costs and some amount of additional restitution — although, again, exactly how much remains unknown.

What to make of this? A careful analysis of that March 1984 document shows that Morse and Amiga abode entirely by the letter of the agreement, that they were perfectly within their rights to return Atari’s loan to them and walk away from any further business arrangements. Atari’s argument rather lay in the spirit of the deal. At its heart is a single line in the agreement to which Morse signed his name that could easily be overlooked as boilerplate, a throwaway amidst all the carefully constructed legalese: “Amiga and Atari agree to negotiate in good faith regarding the license agreement.”

Atari’s contention, which is difficult to deny, was that Morse had at no time been acting in good faith from the moment he put pen to paper on the agreement. The agreement had rather been a desperate gambit to secure enough operating capital to keep Amiga in business for a few more months and find another suitor — nothing more, nothing less. Morse had stalled and obfuscated and dissembled for almost three months, whilst he sought that better suitor. Atari alleged that he had even verbally agreed to a “will not sell to” list of companies not allowed to acquire Amiga under any circumstances even as he was negotiating with one of the most prominent entries on that list, Commodore. And when he had forced a check into Farrand’s hands to terminate the relationship, they claimed, he had done so with the shabby excuse that the chips didn’t work properly, even though the whole world had seen them in action just a few weeks before at Summer CES. No, there wasn’t a whole lot of “good faith” going on there.

That said, the ethics of Morse’s actions, or lack thereof, strike me as far from cut and dried. It’s hard for me to get too morally outraged about Morse screwing over a company that was manifestly bent on screwing him in his position of weakness by saddling him with a terrible licensing proposal, an absurd deadline, and legal leverage that effectively destroyed any hope he might have had to get a reasonable, fair licensing agreement out of them. The letter of intent he felt compelled to sign reads more like an ultimatum than a starting point for negotiations. John Farrand as well as others from Atari claimed in court that they had had no intention of exercising their legal right to go into escrow to build the Amiga chipset without paying anything else at all for it had Morse not delivered that loan repayment in the nick of time. Still, these claims must be read skeptically, especially given Atari’s own desperate business position. Certainly Morse would have been an irresponsible executive indeed to base the fate of his company on their word. If Atari had really wished to acquire the chipset and make an equitable, money-making deal for both parties, they could best have achieved that by not opening negotiations with an absurd three-week deadline that put Morse over a barrel from day one.

That, anyway, is my view. Opinions of others who have studied the issue can and do vary. I would merely caution to consider the full picture anyone eager to read too much into the fact that Atari by relative consensus won this legal battle in the end. Even leaving aside the fact that legal right does not always correspond to moral right, we should remember that other issues eventually got bound up into the case. It strikes me particularly that Atari had quite a strong argument to make for Jay Miner having violated their patents, which covered display hardware uncomfortably similar to that in the Amiga chipset, even down to a graphics co-processor very similar in form and function to the so-called “copper” housed inside Agnus. Without knowing more about the contents of the final settlement, I really can’t say more than that.

As the court battle began, the effort to build the computer that would become known as the Atari ST was also heating up. Shivji had initially been enamored with an oddball series of CPUs from National Semiconductor called the NS32000s, the first fully 32-bit CPUs to hit the industry. When they proved less impressive in reality than they were on paper, however, he quickly shifted to the Motorola 68000 that was already found in the Apple Lisa and Macintosh and the Amiga Lorraine. Generally described as a 16-bit chip, the 68000 was in some ways a hybrid 16- and 32-bit design, a fact which gave the new computer its name: “ST” stands for “Sixteen/Thirty-two Bit.” Shivji had had a very good idea even before Tramiel’s acquisition of Atari of just what he wanted to build:

There was going to be a windowing system, it was going to have bitmapped graphics, we knew roughly speaking what the [screen] resolutions were going to be, and so on. All those parameters were decided before the takeover. The idea was an advanced computer, 16/32-bit, good graphics, good sound, MIDI, the whole thing. A fun computer — but with the latest software technology.

Jack Tramiel and his sons descended on Atari and began with brutal efficiency to separate the wheat from the chaff. Huge numbers of employees got the axe from this company that had already been wracked by layoff after layoff over the past year. The latest victims were often announced impersonally by reading from a list of names in a group meeting, sometimes on the basis of impressions culled from an interview lasting all of five minutes. The bottom line was simple: who could help in an all-out effort to build a sophisticated new computer from the ground up in a matter of months? Those judged wanting in the skills and dedication that would be required were gone. Tramiel sold the equipment, even the desks they had left behind to make quick cash to throw into the ST development effort. With Amiga’s computer and who knew what else in the offing from other companies, speed was his priority. He expected his engineers, starting in August with virtually nothing other than Shivji’s rough design parameters, to build him a prototype ready to be demonstrated at the next CES show in January.

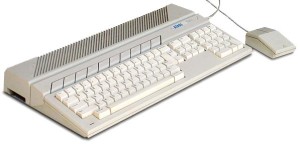

Decent graphics capabilities had to be a priority for the type of computer Shivji envisioned. Therefore the hardware engineers spent much of their time on a custom video chip that would support resolutions of up to 640 X 400, albeit only in black and white; the low-resolution mode of 320 X 200 that would be more typically used by games would allow up to 16 colors onscreen at one time from a palette of 512. That chip aside, to save time and money they would use off-the-shelf components as much as possible, such as a three-voice General Instrument sound chip that had already found a home in the popular Apple II Mockingboard sound card as well as various videogame consoles and standup arcade games. The ST’s most unusual feature would prove to be the built-in MIDI interface that let it control a MIDI-enabled synthesizer without the need for additional hardware, a strange luxury indeed for Tramiel to allow, given that he was famous for demanding that his machines contain only the hardware that absolutely had to be there in the name of keeping production costs down. (For a possible clue to why the MIDI interface was allowed, we can look to a typical ST product demonstration. Pitchmen made a habit of somewhat disingenuously playing MIDI music on the ST that was actually produced by a synthesizer under the table. It was easy — intentionally easy, many suspected — for an observer to miss the mention of the MIDI interface and think the ST was generating the music internally.) And of course in the wake of the Macintosh the ST simply had to ship with a mouse and an operating system to support it.

It was this latter that presented by far the biggest problem. While the fairly conservative hardware of the ST could be put together relatively quickly, writing a modern, GUI-based operating system for the new computer represented a herculean task. Apple, for instance, had spent years on the Macintosh’s operating system, and when the Mac was released it was still riddled with bugs and frustrations. This time around Tramiel wouldn’t be able to just slap an archaic-but-paid-for old PET BASIC ROM into the thing, as he had in the case of the Commodore 64. He needed a real operating system. Quickly. Where to get it?

He found his solution in a very surprising place: at Digital Research, whose CP/M was busily losing its last bits of business-computing market-share to Microsoft’s juggernaut MS-DOS. Digital had adopted an if-you-can’t-beat-em-join-em mentality in response. They were hard at work developing a complete Mac-like window manager that could run on top of MS-DOS or CP/M. It was called GEM, the “Graphical Environment Manager.” GEM was merely one of a whole range of similar shells that were appearing by 1985, struggling with varying degrees of failure to bring that Mac magic to the bland beige world of the IBM clones. Also among them was Microsoft’s original Windows 1.0 — another product that Tramiel briefly considered licensing for the ST. Digital got the nod because they were willing to license both GEM and a CP/M layer to run underneath it fairly cheap, always music to Jack Tramiel’s ears. The only problem was that it all currently ran only on Intel processors, not the 68000.

The small Atari team that temporarily immigrated to Digital Research’s Monterey headquarters to adapt GEM to the ST.

As Shivji and his engineers pieced the hardware together, some dozen of Atari’s top software stars migrated about 70 miles down the California coast from Silicon Valley to the surfer’s paradise of Monterey, home of Digital Research. Working with wire-wrapped prototype hardware that often flaked out for reasons having nothing to do with the software it ran, dealing with the condescension of many on the Digital staff who looked down on their backgrounds as mostly games programmers, wrestling with Digital’s Intel source code that was itself still under development and thus changing constantly, the Atari people managed in a scant few months to port enough of CP/M and GEM to the ST to give Atari something to show on the five prototype machines that Tramiel unveiled at CES in Las Vegas that January. Shivji:

The really exciting thing was that in five months we actually showed the product at CES with real chips, with real PCBs, with real monitors, with real plastic. Five months previous to that there was nothing that existed. You’re talking about tooling for plastic, you’re talking about getting an enormous software task done. And when we went to CES, 85 percent of the machine was done. We had windows, we had all kinds of stuff. People were looking for the VAX that was running all this stuff.

Tramiel was positively gloating at the show, reveling in the new ST and in Atari’s new motto: “Power Without the Price.” Atari erected a series of billboards along the freeway leading from the airport to the Vegas Strip, like the famous Burma-Shave signs of old.

PCjr, $599: IBM, Is This Price Right?

Macintosh, $2195: Does Apple Need This Big A Bite?

Atari Thinks They’re Out Of Sight

Welcome To Atari Country — Regards, Jack

The trade journalists, desperate for a machine to revive the slowing home-computer revolution and with it the various publications they wrote for, ate it up. The ST — or, as the press affectionately dubbed it, the “Jackintosh” — stole the show. “At a glance,” raved Compute! magazine, “it’s hard to tell a GEM screen from a Mac screen” — except for the ST’s color graphics, of course. And one other difference was very clear: an ST with 512 K of memory and monitor would retail for less than $1000 — less than one-third the cost of an equivalent Macintosh.

Rhapsodic press or no, Tramiel’s Atari very nearly went out of business in the months after that CES show. The Atari game consoles as well as the Atari 8-bit line of home computers were all but dead as commercial propositions, killed by the Great Videogame Crash and the Commodore 64 respectively. Thus virtually no money was coming in. You can only keep a multinational corporation in business so long by selling its old office furniture. The software team in Monterey, meanwhile, had to deal with a major crisis when they realized that CP/M just wasn’t going to work properly as the underpinning of GEM on the ST. They ended up porting and completing an abandoned Digital project to create GEMDOS, or, as it would become more popularly known, TOS: the “Tramiel Operating System.” With their software now the last hold-up to getting the ST into production and Tramiel breathing down their necks, the pressure on them was tremendous. Landon Dyer, one of the software team, delivers an anecdote that’s classic Jack Tramiel:

Jack Tramiel called a meeting. We didn’t often meet with him, and it was a big deal. He started by saying, “I hear you are unhappy.” Think of a deep, authoritarian voice, a lot like Darth Vader, and the same attitude, pretty much.

Sorry, Jack, things aren’t going all that hot. We tried to look humble, but we probably just came across as tired.

“I don’t understand why you are unhappy,” he rumbled. “You should be very happy; I am paying your salary. I am the one who is unhappy. The software is late. Why is it so late?”

Young and idealistic, I piped up: “You know, I don’t think we’re in this for the money. I think we just want to ship the best computer we can –”

Jack shut me down. “Then you won’t mind if I cut your salary in half?”

I got the message. He didn’t even have to use the Force.

Somehow they got it done. STs started rolling down production lines in June of 1985. The very first units went on sale not in the United States, where there were some hang-ups acquiring FCC certification, but rather West Germany. It was just as well, underscoring as it did Tramiel’s oft-repeated vision of the ST as an international computing platform. Indeed, the ST would go on to become a major success in West Germany and elsewhere in Europe, not only as a home computer and gaming platform but also as an affordable small-business computer, a market it would not manage to penetrate to any appreciable degree in its home country. Initial sales on both continents were gratifying, and the press largely continued to gush.

The praise was by no means undeserved. If the ST showed a few rough edges, inevitable products of its rushed development on a shoestring budget, it was more notable for everything it did well. A group of very smart, practical people put it together, ending up with a very sweet little computer for the money. Certainly GEM worked far, far better than a hasty port from a completely different architecture had any right to — arguably better, in fact, than Amiga’s soon-to-be-released homegrown equivalent, the Workbench. The ST really was exactly what Jack Tramiel had claimed it would be: a ridiculous amount of computing power for the price. That made it easier to forgive this “Jackintosh’s” failings in comparison to a real Macintosh, like its squat all-in-one-box case — no Tramiel computer was ever likely to win the sorts of design awards that Apple products routinely scooped up by the fistful even then — and materials and workmanship that weren’t quite on the same par with the Mac as were the ST’s raw specs. The historical legacy of the ST as we remember it today is kind of a tragic one in that it has little to do with the machine’s own considerable merits. The tragedy of the ST would be to be merely a very good machine, whereas its two 68000-based points of habitual comparison, the Apple Macintosh and the Commodore Amiga, together pioneered the very paradigm of computing and, one might even say, of living that we know today.

Speaking of which: just where was Commodore in the midst of all this? That’s a question many in the press were asking. Commodore had made an appearance at that January 1985 CES, but only to show off a new 8-bit computer, the last they would ever make: the Commodore 128. An odd, Frankenstein’s monster hybrid of a computer, it seemed a summary of the last ten years of 8-bit development crammed into one machine, sporting both of the microprocessors that made the PC revolution, the Zilog Z-80 and the MOS 6502 (the latter was slightly modified and re-badged the 8502). Between them they allowed for three independent operating modes: CP/M, a 99.9 percent compatible Commodore 64 mode, and the machine’s unique new 128 mode. This latter addressed most of the 64’s most notable failings, including its lack of an 80-column display, its atrocious BASIC that gave access to none of the machine’s graphics or sound capabilities (the 128’s BASIC 7.0 in contrast was amongst the best 8-bit BASICs ever released), and its absurdly slow disk drives (the 128 transferred data at six or seven times the speed of the 64). Despite being thoroughly overshadowed by the ST in CES show reports, the 128 would go on to considerable commercial success, to the tune of some 4 million units sold over the next four years.

Still, it was obvious to even contemporary observers that the Commodore 128 represented the past, the culmination of the line that had begun back in 1977 with the Commodore PET. What about the future? What about Amiga? While Tramiel and his sons trumpeted their plans for the ST line to anyone who would listen, Commodore was weirdly silent about goings-on inside its new division. The press largely had to make do with rumor and innuendo: Commodore had sent large numbers of prototypes to a number of major software developers, most notably Electronic Arts; the graphics had gotten even better since those CES shows; Commodore was planning a major announcement for tomorrow, next week, next month. The Amiga computer became the computer industry’s unicorn, oft-discussed but seldom glimpsed. This, of course, only increased its mystique. How would it compare to the Jackintosh and the Macintosh? What would it do? How much would it cost? What would it, ultimately, be? And just why the hell was it taking so long? A month after Atari started shipping STs — that machine had gone from a back-of-a-napkin proposal to production in far less time than it had taken Commodore to merely finish their own 68000-based computer — people would at long last start to get some answers.

(Sources: On the Edge by Brian Bagnall; New York Times of July 3 1984, August 21 1984, and August 29 1984; Montreal Gazette of July 12 1984 and July 14 1984; Compute! of August 1984, February 1985, March 1985, April 1985, July 1985, August 1985, and October 1985; STart of Summer 1988; InfoWorld of September 17 1984 and December 17 1984; Wall Street Journal of March 25 1984; Philadelphia Inquirer of April 19 1985. Landon Dyer’s terrific memories of working as part of Atari’s GEM team can be found on his blog as a part 1 and a part 2. Finally, Marty Goldberg’s once again shared a lot of insights and information on the legal battle between Atari and Commodore, including some extracts from actual court transcripts, although once again our conclusions about it are quite different. Regardless, my heartfelt thanks to him! Most of the pictures in this article come from STart magazine’s history of the ST, as referenced above.)

The 68000 Wars, Part 1: Lorraine

This is what a revolutionary technology looks like. In very early 1986 Tim Jenison, founder of NewTek, began distributing these full-color digitized photographs, the first of their kind ever to be seen on a PC screen, to Amiga public-domain software exchanges. The age of multimedia computing had arrived.

The Amiga was the damnedest computer. A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, then all crammed into a plastic case; that was the Amiga. I wrote a book about the thing, and I’m still not sure I can make sense of all of its complications and contradictions.

The Amiga was a great computer when it made its debut in 1985, better by far than anything else on the market. At its heart was the wonderchip of the era, the Motorola 68000, the same CPU found in the Apple Macintosh and the Atari ST. But what made the Amiga special was the stuff found around the 68000: three custom chips with the unforgettable names of Paula, Denise, and Agnus. Together they gave the Amiga the best graphics and sound in the industry by a veritable order of magnitude. And by relieving the 68000 of a huge chunk of the burden for generating graphics and sound as well as performing many other tasks, such as disk access, they let the Amiga dazzle while also running rings around the competition in real-world performance by virtually any test you cared to name. It all added up not just to incremental improvement but rather to that rarest thing in any field of endeavor: a generational leap.

The Amiga, especially in its original 1985 incarnation, was a terrible computer. The operating system that shipped with it was painfully buggy. If you could manage to use the machine for just an hour or two without it inexplicably running out of memory and crashing you were doing well. Other glitches were bizarrely entertaining if they didn’t happen to you personally, such as the mysterious “date virus” that could start to spread through all your disks, setting the timestamp on every file to sometime in the year 65,000 and slowing the system to a crawl. (No, this “virus” wasn’t actual malware, just a weird bug.) Of course, software could be and to a large extent eventually was fixed. Other problems were more intractable. There was, for instance, the machine’s use of interlaced video for its higher resolution modes, which caused those marvelous graphics to flicker horribly in most color combinations. Baffled users who felt like their swollen eyeballs were about to pop right out of their heads after a few hours of trying to work like this could expect to be greeted with a lot of technical explanations of why it was happening and suggestions for changing their onscreen color palettes to try to minimize it. Certainly anyone who picked up an Amiga expecting an experience similar to the famously easy-to-use Macintosh was in for a disappointment. Despite the Amiga’s sporting a superficially similar mouse-and-windows interface, users hoping to get serious work or play done on the Amiga would need to educate themselves on such technical minutiae as the difference between “chip” and “fast” memory and learn what a program’s “stack” was and how to set it manually. Even on a good day the Amiga always felt like a house of cards ready to be blown over by the first breath of wind. When the breeze came, the user was left staring at an inscrutable “Guru Meditation Error” and a bunch of intimidating numbers. Sometimes the Amiga could seem positively designed to confound.

The Amiga anticipated the future, marked the beginning of a new era. It pointed forward to the way we live and compute today. I titled my book on the machine The Future Was Here for a reason. That aforementioned generational leap in graphics and sound was the most significant in the history of the personal computer in that it made the Amiga not just a new computer but something qualitatively new under the sun: the world’s first multimedia PC. With an Amiga you could for the first time store and play back in an aesthetically pleasing way imagery and sound captured from the real world, and combine and manipulate and interact with it within the digital environment inside the computer. This changed everything about the way we compute, the way we play, and eventually the way we live, making possible everything from the World Wide Web to the iPod, iPad, and iPhone. Almost as significantly, the Amiga pioneered multitasking on a PC, another feature enabled largely by that magnificent hardware that was able to stretch the 68000 so much farther than other computers. There is considerable psychological research today that indicates that, for better or for worse, multitasking has literally changed the way we think, changed our brains — not a bad claim to fame for any commercial gadget. When you listen to music whilst Skyping on-and-off with a friend whilst trying to get that term paper finished whilst looking for a new pair of shoes on Amazon, you are what the Amiga wrought.

The Amiga was stuck in the past way of doing things, thus marking the end of an era as well as the beginning of one. It was the punctuation mark at the end of the wild-and-wooly first decade of the American PC, the last time an American company would dare to release a brand new machine that was completely incompatible with what had come before. Its hardware design reflected the past as much as the future. Those custom chips, coupled together and to the 68000 so tightly that not a cycle was wasted, were a beautiful piece of high-wire engineering created by a bare handful of brilliant individuals. If a computer can be a work of art, the Amiga certainly qualified. Yet its design was also an evolutionary dead end; the custom chips and all the rest were all but impossible to pull apart and improve without breaking all of the software that had come before. The future would lie with modular, expandable design frameworks like those employed by the IBM PC and its clones, open hardware (and software) standards that were nowhere near as sexy or as elegant but that could grow and improve with time.

The Amiga was a great success, the last such before the Wintel hegemony expanded to dominate home computing like it already did business by the mid-1980s. Its gaming legacy is amongst the richest of any platform ever, including some fifteen years worth of titles that, especially during the first half of that period, broke boundaries at every turn and expanded the very notion of what a computer game could be. I won’t even begin to list here the groundbreaking classics that were born on the Amiga; suffice to say that they’ll be featuring in this blog for years to come. The Amiga was so popular a gaming platform in Europe that it survived many years after the death of its corporate parent Commodore, a phenomenon unprecedented in consumer computing. The last of the many glossy newsstand magazines devoted to it, Britain’s Amiga Active, didn’t cease publication until November of 2001, well over seven years after the platform became an orphan. It would prove to be just as long-lived in its other major niche of video-production workstation. Thanks to their unique ability to blend their own visuals with analog video signals — enabled, ironically, by those very same interlaced video modes that drove so many users crazy — Amigas could be found in the back rooms of small cable stations and video producers into the 2000s. Only the great changeover to digital HD broadcasting finally and definitively put an end to the Amiga’s career in this realm.

The Amiga was a bitter failure, one of the great might-have-beens of computer history. In 1985 so many expected it to become so much more than just another game machine or even “just” the pioneer of the whole new field of desktop video, forerunner of the YouTube generation. The Amiga, believed its early adopters, was so much better — not just technically better but conceptually better — than what was already out there that it was surely destined to conquer the world. After all, business-software heavy hitters like WordPerfect, Borland, Ashton-Tate, and Lotus knew a good thing when they saw it, were already porting their applications to it. And yet in the end only WordPerfect came through, for a while, and, while the Amiga did change the world in the long term, its innovations were refined and made into everyday life by Apple and Microsoft rather than the Amiga itself. The vast majority of heirs to the Amiga’s legacy today — a number which includes virtually every citizen of the developed world — have no idea a computer called the Amiga ever existed.

That’s just a sample of the contradictions awaiting any writer who tries to seriously tackle the Amiga as a subject. And there’s also another, more ironic sort of difficulty to be confronted: the sheer love the Amiga generated on the part of so many who had one. The Amiga, I must confess, was my own first computing love. Since that day in 1994 when I gave in and bought my first Wintel machine, I’ve been platform-agnostic. Linux and Apple zealots and Microsoft apologists all leave me cold, leave me wondering how people can get so passionate about any platform not called Amiga. Of course I’m smart enough to realize that none of this is really all that important, that a gadget is just that, a means to an end. I even recognize that, had the Amiga not come along when it did to pioneer a new paradigm for computing, something else would have. That’s just how history works. But still, there was something special about the Amiga for those of us who were there, something going far beyond even a hacker’s typical love for his first computer.

To say Amiga users had — still have — a reputation for zealotry hardly begins to state the case. General-computing magazines from the late 1980s until well into the 1990s learned to expect a deluge of hate mail from Amiga users every time they published an article that dared say an unfavorable word about the platform — or, worse, and as inevitably happened more and more frequently as time went on and the Amiga faded further from prominence, that didn’t mention it at all. Prominent mainstream columnist John C. Dvorak liked to say that, whereas Mac users were just arrogant and self-righteous, Amiga users were actively delusional. There are still folks out there clinging to their 25-year-old Amigas, patched together with the proverbial duct tape and baling wire, as their primary computing platform. A disturbing number of them are still waiting for the day when the Amiga shall rise again and take over the world, even as it’s hard to understand what a modern Amiga should even be or why it should exist in a world that long since incorporated all of the platform’s best ideas into slicker, simpler gadgets.

Every good cult needs an origin myth, and the Cult of Amiga is no exception. Beginning already in the machine’s North American heyday of the late 1980s, High Priest R.J. Mical, developer of the Amiga’s Intuition library of GUI widgets as well as other critical pieces of its software infrastructure, began traveling to trade shows and conventions telling in an unabashedly sentimental way the story of those earliest days, when the Amiga was being developed by a tiny independent company, itself called simply Amiga, Incorporated.

We were trying to find people that had fire, that had spirit, that had a dream they were trying to accomplish. Carl Sassenrath, the guy that did the Exec for the machine, it was his lifelong dream to do a multitasking operating system that would be a work of art, that would be a thing of beauty. Dale Luck, the guy that did the graphics, this was his undying dream since he was in college to do this incredible graphics stuff.

We were looking for people with that kind of passion, that kind of spirit. More than anything else, the thing that we were looking for was people who were trying to make a mark on the world, not just in the industry but on the world in general. We were looking for people that really wanted to make a statement, that really wanted to do an incredibly great thing, not just someone who was looking for a job.

Yes. Well. While idealism certainly has its place in the Amiga story, the story is also a very down-to-earth tale of competition inside Silicon Valley. It begins in 1982 with an old friend of ours: Larry Kaplan, one of the Fantastic Four game programmers from Atari who founded Activision along with Jim Levy.

Activison was flying high in 1982, the Fantastic Four provided in Kaplan’s own words with “limousine service, company cars, and a private chef” on top of a base salary of $150,000. Yet Kaplan, who is often described by others as the very apotheosis of “the grass is always greener,” was restless. He had the idea to form another company, one all his own this time, to enter the booming Atari VCS market. One day in early 1982 he called up an old colleague of his from the Atari days: Jay Miner, who had designed the Atari VCS’s display chip, then gone on to design the chipset at the heart of the Atari 400 and 800 home computers. Kaplan, along with two others of the Fantastic Four, had written the operating system and BASIC language implementation for those machines. He thus knew Miner well. Knowing the vagaries of business and starting his own company somewhat less well than he knew Miner and programming, his initial query was a simple one: “I’d like to start a company. Do you know any lawyers?”

Miner, who had left Atari at around the same time as the Fantastic Four out of a similar disgust with new CEO Ray Kassar, had also left Silicon Valley to move to Freeport, Texas, where he worked for a small semiconductor company called Zymos, designing chips for pacemakers and other medical devices. Miner said that, no, he wasn’t particularly well-acquainted with any lawyers, good or otherwise, but that his boss, Zymos founder Bert Braddock, had a pretty good head for business. He made the introduction, and Kaplan and Braddock hit it off. The plan that Kaplan presented to him was to combine hardware and software in the booming home videogame space, offering hardware to improve on the Atari VCS’s decidedly limited capabilities along with game cartridges that took advantage of the additional gadgetry. Such a scheme was hardly original to him; confronted with the VCS’s enormous popularity and equally enormous limitations, others were already working the same space. For example, two other former Atari engineers, Bob Brown and Craig Nelson, had already formed Starpath to develop a “Supercharger” hardware expansion for the VCS as well as games to play with it. (Starpath would go on to merge with the newly renamed Epyx — née Automated Simulations — and write games like Summer Games.)

Nevertheless, Braddock sensed a potentially fruitful partnership in the offing for a maker of chips like his Zymos. He found Kaplan some investors in nearby oil-rich Houston to put up the first $1 million or so to get the company off the ground. He also found and recruited one Dave Morse, a vice president of marketing at Tonka Toys, to join Kaplan, believing him to be exactly the savvy business mind and shrewd negotiator the venture needed. An informal agreement was reached amongst the group: Morse would run the new company; Kaplan would write the games; Miner (working under contract, being still employed by Zymos) would design the ancillary hardware; and Zymos would manufacture the hardware and the game cartridges. Somewhere at the back of everyone’s mind was the idea that, if they were successful with their games and add-on gadgets, they might just be able to take the next step: to make a complete original game console of their own, the successor to the Atari VCS that Ray Kassar’s Atari didn’t seem all that interested in seriously pursuing.

In June of 1982, Kaplan announced to his shocked colleagues at Activision that he was moving on to do his own thing; the bridges he thus burnt have never been mended to this day. He and Morse opened a small office in Santa Clara, California, for their new company, which Kaplan named Hi-Toro. Morse and Braddock — truly a sugar daddy to die for for a fledgling corporation — beat the bushes over the months that followed for additional financing, with success to the tune of another $5 million or so. The majority were dentists and other members of the medical establishment, thanks to Braddock’s connections in that field. They knew little to nothing about computer technology, but knew very well that videogames were hot, and were eager to get in on the ground floor of another Atari.

And then the squirrely Larry Kaplan nearly undid the whole thing. He called Atari founder Nolan Bushnell that October to talk up his new company, hoping to convince him to join Hi-Toro as chairman of the board; a name like his would confer instant legitimacy. Instead the hunter became the hunted. Bushnell, who was legendary for the buckets of charm at his fingertips, convinced Kaplan to come to him, convinced him they could start a new videogame company to rival Atari together, without Zymos or Morse or Miner. Just like that, Kaplan tendered his second shocking resignation of 1982. In the end, as Kaplan later put it, “Nolan, of course, flaked out,” leaving him high and dry, if quite possibly deservedly so. He would end up completing the circle by going back to Atari before the year was up, but that gig ended when the Great Videogame Crash of 1983 hit. Widely regarded as too untrustworthy to be worth the trouble inside the industry by that point, Kaplan’s career never recovered. On the plus side, he was able to cash out his Activision stock following that company’s IPO, making him quite a wealthy man and making future work largely optional anyway — not the worst of petards for a modern-day Claudius.

Dave Morse, meanwhile, was also left high and dry, with a company and an office and lots of financing but nobody to design his products. He asked Jay Miner to leave Zymos and join him full-time at Hi-Toro, to help fill the vacuum left by Kaplan’s departure. Miner, who had been nursing for some time now a dream of doing a game console and/or a computer based around the new Motorola 68000 and who saw Hi-Toro as just possibly his one and only chance to do that, agreed — so long as he could bring his beloved cockapoo Mitchy with him to the office every day.

One of the first things to go after Kaplan left was the company name he had come up with. Everyone Morse and Miner spoke to agreed that “Hi-Toro” was a terrible name that made one think of nothing so much as lawn mowers. Morse therefore started flipping through a dictionary one day, looking for something that would come before Apple and Atari in corporate directories. He hit upon the Spanish word for “friend”: “amigo.” That had a nice ring to it, especially with “user-friendliness” being one of the buzzwords of the era. But the feminine version of the word — “amiga” — sounded even better, friendly and elegant maybe even a little bit sexy. Miner by his own later admission was ambivalent about the new name, but everyone Morse spoke to seemed very taken with it, so he let it go. Thus did Hi-Toro become Amiga.

Of course, Morse and Miner couldn’t do all the work by themselves. Over the months that followed they assembled a team whose names would go down in hacker lore. An old colleague from Atari who had worked with Miner on the VCS as well as the 400 and 800, Joe Decuir, came in under a temporary contract to help Miner start work on a new set of custom chips. A few other young hardware engineers were hired as full-time employees. Morse hired one Bob Pariseau to put together a software team; he became essentially the equivalent of Jay Miner on that side of the house. The software people would soon grow to outnumber the hardware people. Among their ranks were now-legendary Amiga names like R.J. Mical, Dale Luck, and Carl Sassenrath.

The folks who came to work at Amiga were almost universally young and largely inexperienced. While tarring them with the clichéd “dreamers and misfits” label may be going too far, it is true that their backgrounds were more diverse than the Silicon Valley norm; Mical, for instance, was a failed English major who had recently spent nine months backpacking his way around the world. While their youthful idealism would do much to give the eventual Amiga computer its character, there was also a very practical reason that Morse had to fill his office with all these bright young sparks: what with financing getting harder and harder to come by as the videogame industry began to go distinctly soft, he simply couldn’t afford to pay for more experienced hands. Amiga’s financial difficulties provided the opportunity of a lifetime to a bunch of folks that may have struggled to get in the door in even the most junior of positions at someplace like Apple, IBM, or Microsoft.

The glaring exception to the demographic rule at Amiga was Jay Miner himself. Creative, bleeding-edge engineering is normally a young person’s game. Miner, however, was fully 50 years old when he created his masterpiece, the Amiga chipset. He’d been designing circuits already twenty years before the microprocessor even existed and well before some of his colleagues around the office were even born. Thanks perhaps to intermittent but chronic kidney problems that would eventually kill him at age 62, he looked and in some ways acted even older than his years, favoring quiet, contemplative hobbies like cultivating bonsai trees and carving model airplanes out of balsa wood. Adjectives like “fatherly” rival “soft-spoken” and “wise” in popularity when people who knew him remember him today. While the higher-strung Dave Morse became the face Amiga showed to the outside world, Miner set the internal tone, tolerating and even encouraging the cheerful insanity that was life inside the Amiga offices. Miner:

The great things about working on the Amiga? Number one I was allowed to take my dog to work, and that set the tone for the whole atmosphere of the place. It was more than just companionship with Mitchy — the fact that she was there meant that the other people wouldn’t be too critical of some of those we hired, who were quite frankly weird. There were guys coming to work in purple tights and pink bunny slippers. Dale Luck looked like your average off-the-street homeless hippy with long hair and was pretty laid-back. In fact the whole group was pretty laid-back. I wasn’t about to say anything — I knew talent when I saw it and even Parasseau who spread the word was a bit weird in a lot of ways. The job gets done and that’s all that matters. I didn’t care how solutions came about even if people were working at home.

The question of just what this group was working on, and when, is a harder question to answer than you might expect. When we use the word “Amiga” to refer to this era, we could be talking about any of three possibilities. Firstly, there’s Amiga the company, which during its early months put well over half of its personnel and resources into games and add-ons for the old Atari VCS rather than revolutionary new technology. Then there’s the Amiga chipset being designed by Miner and his team. And finally there’s a completed game console and/or computer to incorporate the chipset. Making sense of this tangle is complicated by revisionist retellings, which tend to find grand plans and coherent narratives where none actually existed. So, let’s take a careful look at each of these Amigas, one at a time.

Kaplan’s original plan had envisioned Hi-Toro/Amiga as a maker first and foremost of cartridges and hardware add-ons for the VCS, with a whole new console possibly to follow if things went gangbusters. These plans got reprioritized somewhat when Kaplan left and Miner came aboard with his eagerness to do a console and/or computer, but they were by no means entirely discarded. Thus Amiga did indeed create a handful of original games over the course of 1983, along with joysticks and other hardware. By far the most innovative and best-remembered of these products was something called the Joyboard: a large, flat slab of plastic on which the player stood and leaned side to side and front to back to control a game in lieu of a joystick. Amiga packaged a skiing game, Mogul Maniac, with the Joyboard, and developed at least two more — a surfing game called Surf’s Up and a pattern-matching exercise called Off Your Rocker — that never saw release. The Joyboard and its companion products have been frequently characterized as little more than elaborate ruses designed to keep the real Amiga project under wraps. In reality, though, Morse had high commercial hopes for this side of his company; he was in fact depending on these products to fund the other side of the operation. He spent quite lavishly to give the Joyboard a splashy introduction at the New York Toy Fair in February of 1983, and briefly hired former Olympic skier Suzy Chaffee — better known to a generation of Americans as “Suzy Chapstick” thanks to her long-running endorsement of that brand — to serve as spokesperson. His plans were undone by the Great Videogame Crash. The peripherals and games all failed miserably, precipitating a financial crisis at Amiga to which I’ll return shortly.

The chips were always Jay Miner’s babies. Known in the early days as Portia, Daphne, and Agnus, later iterations would see Portia renamed to Paula and Daphne to Denise. Combined with a 68000, they offered unprecedented audiovisual capabilities, including a palette of 4096 colors and four-channel stereo sound. Their most innovative features were the so-called “copper” and “blitter” housed inside Agnus. The former, which could also be found in a less advanced version in Miner’s previous Atari 400 and 800, could run short programs independent of the CPU to change the display setup on the fly in response to the perpetually repainting electron gun behind the television or monitor reaching certain points in its cycle. This opened the door to a whole universe of visual trickery. The blitter, meanwhile, could be programmed to copy blocks of memory from place to place at lightning speeds, and in the process perform transformations and combinations on the data — once again, independent of the CPU. It was a miracle worker in the realm of fast animation. While not programmable in the same sense as the copper and the blitter, Denise autonomously handled the task of actually painting the display, while Paula could autonomously play back up to four sound samples or waveforms at a time, and also independently handle input and output to disk. (This is the briefest of technical summaries of the Amiga chipset. For a detailed description of the chipset’s internal workings as well as many important aspects of its host platform’s history that I’ll never get to in this game-focused blog, I point you again to my own book on the subject.)

Amiga’s ultimate vision for their chipset — whether in the form of a game console, a computer, a standup arcade game, or all three — is the most difficult part of all their tangled skein of intentionality to unravel, and the one most subject to revisionist history. Amiga fanatics of later years, desperate to have their platform accepted as a “serious” computer like the IBM PC or Apple Macintosh, became rather ashamed of its origins in the videogame industry. This has occasionally led them to say that the Amiga was always secretly intended to be a computer, that the videogame plans were just there to fool the investors and keep the money flowing. In truth, there’s good reason to question whether there was any real long-term plan at all. Miner noted in later interviews that the company was quite split on the subject, with — ironically in light of his later status of Amiga High Priest — R.J. Mical on the “investors’ side,” pushing for a low-cost game console, while others like Dale Luck and Carl Sassenrath wanted an Amiga computer. Miner himself claimed to have envisioned a console that could be expanded into a real computer with the addition of an optional keyboard and disk drive. (Amiga also had similar plans for the Atari VCS in the form of something to be called the Amiga Power Module, yet another project killed by the videogame collapse.) Dave Morse, who died in 2007, is not on record at all on the subject. One suspects that he was simply in wait-and-see mode through much of 1983.

What is clear is that the first Amiga machine to be shown to the public wasn’t so much a prototype of a real or potential computer or game console as the most minimalist possible frame to show off the capabilities of the Amiga chipset. Named after Morse’s wife, the Amiga Lorraine began to come together in the dying days of 1983, in a mad scramble leading up to the Winter Consumer Electronics Show that was scheduled to begin on January 4. Any mad scientist would have been proud to lay claim to the contraption. Miner and his team built their chipset, destined eventually to be miniaturized and etched into silicon, out of off-the-shelf electronics components, creating a pile of breadboards large enough to fill a kitchen table, linked together by a spaghetti-like tangle of wires, often precariously held in place with simple alligator clips. It had no keyboard or other input method; the software team wrote programs for it on a workstation-class 68000-based computer called the Sage IV, then uploaded them to the Lorraine and ran them via a cabled connection. The whole mess was a nightmare to maintain, with wires constantly falling off, pieces overheating, or circuits shorting out seemingly at random. But when it worked it provided the first tangible demonstration of Miner’s extraordinary design. Amiga accordingly packed it all up and transported it — very carefully! — to Las Vegas for its coming-out party at Winter CES.

R.J. Mical and Dale Luck, amongst others, had worked feverishly to create a handful of demos to show off in a private corner of Amiga’s CES booth, open only by invitation to hand-selected members of the press and industry. The hit of the bunch, written by Mical and Luck at the show itself in one feverish all-night hacking session fueled by “a six pack of warm beer,” was a huge, checked soccer ball that bounced up and down, prototype of one of the most famous computerized demos of all time. The bouncing soccer ball — the “boing” ball — would soon become the unofficial symbol of Amiga.

Boing and the other demos were impressive, but the hardware was obviously still in a very rough state, still a long, long way away from any sort of salable product. Many observers were frankly skeptical whether this mass of breadboards and wires even could be turned into the three chips Amiga promised, and if so whether those chips could, complicated as they must inevitably be, be cost-effectively manufactured. Two obvious applications of the chipset, to a new videogame console or to standup arcade games, were facing a gale-force headwind following the Great Videogame Crash of the previous year. Nobody wanted anything to do with that market anymore. And introducing yet another incompatible computer into the market, no matter how impressive its hardware, looked like a high-risk proposition as well. Thus most visitors were impressed but carefully noncommittal. Was there really a place for Amiga’s admittedly extraordinary technology? That was the question. Tellingly, of the glossy magazines, only Creative Computing bothered to write about Lorraine in any real detail, excitedly declaring it to have “the most amazing graphics and sound that will ever have been offered in the consumer market.” (Just to show that prescience isn’t always an either/or proposition, the same journalist, John J. Anderson, noted how important it would be to make sure any eventual Amiga computer was compatible with the IBM PCjr, which was sure to take over the industry.)

Thus Amiga’s coming-out party is best characterized as having mixed results on the whole, leading to lots of impressed observers but no new investors. And that was a big, big problem because Amiga was quickly running out of money. With the VCS products having not only failed to sell but also absorbed millions in their own right to develop, Amiga’s financial picture was getting more desperate by the week. One thing was becoming clear: there was no way they were going to be able to secure the investment needed to turn the Lorraine into a completed computer — or a completed anything else — and market it themselves. It seemed that they had three options: license the technology to someone else with deeper pockets, sell themselves outright to someone else, or go quietly out of business. As the founders mortgaged their houses to make payroll and Morse begged his creditors for loan extensions, the only company that seemed seriously interested in the Amiga chipset was the one Jay Miner would least prefer to get in bed with once again: Atari.

An Atari old-timer named Mike Albaugh had first visited Amiga well before the CES show, in November of 1983. He was given an overview of the as-yet-extant-on-paper-only chipset’s features and, knowing very well the capabilities of Jay Miner, expressed cautious interest. After their first tangible glimpse of the chipset’s capabilities at CES, Atari got serious about acquiring this incredible technology from a company that seemed all but at their mercy, desperate to make a deal that would let them stay alive a little longer. With no other realistic options on the table, Dave Morse negotiated with Atari as best he could from his position of weakness. Atari had no interest in buying a completed machine, whether of the game-console or computer variety. They just wanted that wonderful chipset. The preliminary letter of intent that Amiga and Atari signed on March 7, 1984, reflects this.

That same letter of intent, and the $500,000 that Atari transferred to Amiga as part of it, would lead to a legal imbroglio lasting years. The specifics that the letter contained, as well as — equally importantly — what it did not contain, remain persistently misunderstood to this day. Thankfully, the original agreement has been preserved and made available online by Atari historians Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel. I’ve taken the time to parse this document closely, and also enlisted the aid of a couple of acquaintances with better legal and financial minds than my own. Because it’s so critical to the story of Amiga, and because it’s been so widely misunderstood and misconstrued, I think it’s worth taking a moment here to look fairly closely at its specifics.

The document outlines a proposed arrangement granting Atari exclusive license to the chipset for use in home videogame consoles and standup arcade games, in perpetuity from the time that the finalized agreement is signed. The proposal also grants Atari a nonexclusive license to use the chips in a personal computer, subject to the restriction that Atari may first offer an add-on kit to turn a game console using the chips into a full-blown computer in June of 1985, and a standalone computer using the chips only in March of 1986. Before and continuing after Atari makes their computer using the chips, Amiga may make one of their own, but may only sell it through specialized computer dealers, not mass merchandisers like Sears or Toys ‘R’ Us. Atari, conversely, will be restricted to the mass merchandisers. The obvious intention here is to target Amiga’s products to the high-end, professional market, Atari’s to gamers and casual users. Atari will pay Amiga a royalty of $2 per computer or game console containing the chipset sold, $15 per standup arcade videogame. Note that the terms I’ve just described are only a proposal pending a finalized license agreement, without legal force — unless certain things happen to automatically trigger their going into effect, which I’ll get to momentarily.

Now let’s look at the parts of the document that do have immediate legal force. Amiga being starved for cash and still needing to do considerable work to complete the chipset, Atari will give Amiga an immediate “loan” of $500,000, albeit one which they never really expect to see paid back; again, I’ll explain why momentarily. Atari will then continue to give Amiga more loans on a milestone basis: $1 million when a finalized licensing agreement is signed; $500,000 when each of the three chips is completed and delivered to Atari ready for manufacturing. And here’s where things get tricky: once all of the chips are delivered and a licensing agreement is in place, Amiga’s outstanding loan obligations will be converted into a purchase by Atari of $3 million worth of Amiga stock. If, on the other hand, a finalized licensing agreement has not been signed by March 31 — just three weeks from the date of this preliminary agreement — Amiga will be expected to pay back the $500,000 to Atari by June 30, plus interest of 120 percent of the current Bank of America prime rate, assuming some other deal is not negotiated in the interim. If Amiga cannot or will not do so, the proposed licensing agreement outlined above will automatically go into effect as a legally binding contract, with the one very significant change that Atari will not need to pay any royalties at all — the license “shall be fully paid in exchange for cancellation of the loan.” The Amiga chipset thus serves as collateral for the loan, its blueprints and technical specifications being held in escrow by a neutral third party (the Bank of America).

There are plenty of other technicalities — for instance, Atari will be allowed to bill Amiga for their time and other resources if Amiga fails to complete the chipset, thus forcing Atari’s engineers to finish the job — but I believe I’ve covered the salient points here. (Those deeply interested or skeptical of my conclusions may want to look at a more detailed summary I prepared, or, best of all, just have a look at the original.) Looking at the contract, what jumps out first is that it wasn’t a particularly good deal for Amiga. To pay a mere $2 per console or computer sold when the chipset being paid for must be the component that literally makes that console or computer what it is seems shabby indeed. For Atari it would have represented the steal of the century. Why would Morse sign such an awful deal?

The obvious answer must of course be that he was desperate. While it’s perhaps dangerous to ascribe too much motivation to a dead man who never publicly commented on the subject, circumstantial evidence would seem to characterize this agreement as the wind-up to a final Hail Mary, a way to secure a quick $500,000 for the here and now, to keep the lights on a little longer and hope for a miracle. Morse did not sign a final licensing agreement by March 31, a very risky move indeed, as it gave Atari the right to automatically start using Amiga’s chipset, without having to pay Amiga another cent, if Morse couldn’t negotiate some other arrangement with them or find some way to pay back the $500,000 plus interest before June 30. Carl Sassenrath once described Morse as “my model for how to be cool in business.” Truly he must have had nerves of steel. And, incredibly, he would get his miracle.

(Sources: On the Edge by Brian Bagnall. Amiga User International of June 1988 and March 1993. Info of January/February 1987 and July/August 1988. Creative Computing of April 1984. Amazing Computing, premiere issue. InfoWorld of July 12 1982. Commander of August 1983. Scott Stilphen’s interview with Larry Kaplan on the 2600 Connection website. Thanks also to Marty Goldberg for patiently corresponding with me and giving me Atari’s perspective, although I believe his conclusions about the Amiga/Atari negotiations and particularly his reading of the March 7 1984 agreement to be in error. And yeah, there’s my own book too…)

MicroProse’s Simulation-Industrial Complex (or, The Ballad of Sid and Wild Bill)

Change was in the air as the 1980s began, the drawn-out 1960s hangover that had been the 1970s giving way to the Reagan Revolution. The closing of Studio 54 and the release of Can’t Stop the Music, the movie that inspired John J.B. Wilson to start the Razzies, marked the end of disco decadence. John Lennon, whilst pontificating in interviews on the joys of baking bread, released an album milquetoast enough to play alongside Christopher Cross and Neil Diamond on Adult Contemporary stations — prior to getting shot, that is, thus providing a more definite punctuation mark on the end of 1960s radicalism. Another counterculture icon, Jerry Rubin, was left to give voice to the transformation in worldview that so many of his less famous contemporaries were also undergoing. This man who had attempted to enter a pig into the 1968 Presidential election in the name of activist “guerrilla theater” became a stockbroker on the same Wall Street where he had once led protests. “Money and financial interest will capture the passion of the ’80s,” he declared. The 1982 sitcom Family Ties gave the world Steven and Elyse Keaton, a pair of aging hippies who are raising an arch-conservative disciple of Ronald Reagan; it was thus the mirror image of 1970s comedies like All in the Family. Michael J. Fox’s perpetually tie-sporting Alex P. Keaton became a teenage heartthrob because, as Huey Lewis would soon be singing, it was now “Hip to be Square.” Yes, that was true even in the world of rock and roll, where bland-looking fellows like Huey Lewis and Phil Collins, who might very well have inhabited the cubicle next to yours at an accounting firm, were improbably selling millions of records and seeing their mugs all over MTV.

No institution benefited more from this rolling back of the countercultural tide than the American military. Just prior to Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the military’s morale as well as its public reputation were at their lowest ebb of the century. All four services were widely perceived as a refuge for psychopaths, deadbeats, and, increasingly, druggies. A leaked internal survey conducted by the Pentagon in 1980 found that about 27 percent of all military personnel were willing to admit to using illegal drugs at least once per month; the real numbers were almost certainly higher. Another survey found that one in twelve of American soldiers stationed in West Germany, the very front line of the Cold War, had a daily hashish habit. In the minds of many, only a comprehensively baked military could explain a colossal cock-up like the failed attempt to rescue American hostages in Iran in April of 1980, which managed to lose eight soldiers, six helicopters, and a C-130 transport plane without ever even making contact with the enemy. Small wonder that this bunch had been booted out of Vietnam with their tails between their legs by a bunch of shoeless rebels in black pajamas.