As Infocom settled into their middle and latter period, their game releases also settled into a fairly predictable pattern that tried to balance innovation with traditionalism. Steve Meretzky:

The hardcore gamers, the people who liked Zork and just wanted more like Zork from Infocom, they were always made unhappy by [games like] A Mind Forever Voyaging or Plundered Hearts or Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It. Anything that we did that was moving in a different direction or in any way experimental, they would always squawk. So the company’s plan was basically to try to do some of each, to always do a game or two every year that would be the “red meat” for those original hardcore players, and then to try to innovate with some of the other games each year.

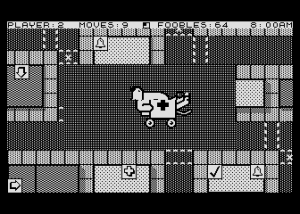

Our subject for today, Spellbreaker, was the long-awaited third game in the Enchanter trilogy as well as Infocom’s most blatant of all bits of pandering to these traditionalists, who made up a much larger percentage of the company’s fan base than Infocom’s modern reputation for relentless innovation and dedication to the literary aspects of the humble text adventure might seem to imply. An “Expert” level game, it was explicitly created by Dave Lebling as a response to the carping of the hardcore of the hardcore that Infocom’s games had been getting much too easy since the days of Zork. “You want a diamond-hard, traditional puzzlefest?” Infocom asked. “Fine, we’ll give you a diamond-hard, traditional puzzlefest!” Coming out just weeks after the radical departure that was A Mind Forever Voyaging, Spellbreaker could almost be read as an apology to the hardcore for that namby-pamby, touchy-feely effort.

That said, it should also be noted that the concerns about creeping easiness, engendered by an ever more thorough testing process and the thoroughgoing sense of fair play that was always one of Infocom’s noblest traits, were not confined to fans outside the company. Meretzky himself, the perpetrator of A Mind Forever Voyaging, has noted that he also felt concerned as time wore on that at least certain types of Infocom games were losing some of their core appeal, that the struggle and sweat of the Zork games, the compulsion to jump out of bed in the middle of the night to test out some crazy action that just might solve a heretofore intractable puzzle, was the very thing that drew many people to them. Spellbreaker would be Infocom’s attempt to rekindle the masochistic joy of Zork.

There’s always a tendency in all forms of criticism to fetishize innovation over virtually everything else; music critics, for instance, will always favor the Clash, who morphed and relentlessly experimented and soon collapsed under the sheer weight of their artistic ambitions, over their punk-era counterparts Stiff Little Fingers, who have just continued to do what they’re good at for decades. It’s an understandable and even defensible impulse, but I also have to confess that, just as I’m more likely to pull out Stiff Little Fingers’s Go For It! than any Clash album, if you asked me which game among A Mind Forever Voyaging and Spellbreaker I most enjoy just playing every five to ten years, I’d have to name Spellbreaker. Spellbreaker is as constrained a design as A Mind Forever Voyaging is boundary-shattering: constrained by its need to please the puzzle-hungry hardcore, by its need to fit in with the two previous games of the Enchanter trilogy and continue with their spell-based puzzle mechanics and Zorkian fantasy premises. But it’s also an absolutely brilliant specimen of traditionalist adventure gaming, one of the best, tightest examples of pure game design Infocom ever crafted.

As old school as its sensibilities may appear in comparison to its immediate predecessor, Spellbreaker is not devoid of theoretical or historical interest. Far from it. In its quiet way, it asserts a profoundly important idea for the craft of adventure-game design: that fairness and difficulty are two independent scales. If virtually any of Infocom’s contemporaries decided to make a self-consciously difficult game like Spellbreaker, they would have simply filled it with punishing mazes and riddles and guess-the-verb problems and inscrutable puzzles dependent on unmotivated actions. We know this because that’s exactly what they did, over and over again. (For instance, have a look at Scott Adams’s two-part alleged brain-burner Savage Island for everything not to do in an adventure game in one convenient place). Certain designers never could seem to separate fairness from difficulty in their minds. (I can’t help but think of Anita Sinclair, who pronounced on the eve of Magnetic Scrolls’s second release Guild of Thieves that this would be an “easier” game. Actually, no, it turned out to be a very hard game — just one that wasn’t blatantly, repeatedly unfair like its predecessor The Pawn.) Many fans still have trouble with the concept today; I get occasional emails in response to my coverage of notable offenders like Roberta Williams’s The Wizard and the Princess and Time Zone asking why I’m so hard on “difficult” games, forcing me to respond that, no, I’m actually only hard on unfair games. One could advance a fairly compelling argument that the failure of the adventure-game industry at large to grasp this distinction played a big part in the commercial death of the text adventure — how many veteran gamers still remember the form largely for mazes, guess-the-verb, and illogical puzzles? — as well as the longstanding commercial doldrums of graphical adventures, what with their pixel hunts and click-everywhere-and-use-everything-on-everything-else-until-something-happens model of game design.

Spellbreaker is very tough, but it’s also downright noble in its commitment to fairness. There is, if you’ll pardon me, no bullshit here, none of the cheap tricks, designed and implemented in less time than it takes to drink a cup of coffee, that designers have so often used to artificially lengthen games and make players pull their hair out. You don’t even need to draw a map to play Spellbreaker — but never fear, you will likely want pen and paper to sketch and plan and diagram a long series of tantalizing puzzles that have been lovingly crafted over days and weeks. In my book, that’s the way a game like this ought to be. Spellbreaker is a veritable capsule history of adventure-game puzzles (the good ones, that is): intricate pure spatial and mathematical puzzles like those so common in the Phoenix games; clever object-application puzzles; logistical puzzles requiring long-term planning; the best and most satisfying application yet of the spell system invented for Enchanter; the latest and greatest and most intricate in an ongoing series of Infocom time-travel puzzles; even a social-interaction puzzle to keep you on your toes. And there are lots and lots of them. While it runs under the standard 128 K Z-Machine, Spellbreaker stuffs it right to its limit, and will take quite some hours to complete. There are one or two puzzles that I might wish had been a bit less difficult — most notably a certain puzzle that takes place in a lava field and hinges on a property of a certain little box that you’re unlikely to discover until you really have exhausted every possibility for experimentation — but none that I can label truly unfair if we’re willing to give the game a free pass on Graham Nelson’s prohibitions against the occasional need for knowledge of future events and knowledge gained from dying. The key thing is that you can trust Spellbreaker as you try to beat it, can trust that the solution to the puzzle on which you’re currently working can be arrived at through observation and deduction rather than being some random phrase to be typed or senseless action to perform. I can’t emphasize enough what a difference this trust — or, perhaps better said, its absence in so many other games — makes for the player’s experience.

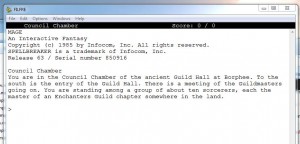

The plot is obviously not the first priority for either player or writer of a game like this, but Spellbreaker‘s is in some ways more interesting than it ought to be. Having averted two previous disasters in Enchanter and Sorcerer, you’ve been elevated to head of the Circle of Enchanters. But now suddenly magic itself has begun to fail throughout the realm. The game opens at a conclave of Guildmasters that has been called to address the problem. Lebling was, along with Brian Moriarty and perhaps Jeff O’Neill, the best crafter of prose amongst all the Imps, and his writing is particularly good here, sparkling with subtle wit.

Sneffle of the Guild of Bakers is addressing the gathering. "Do you know what this is doing to our business? Do you know how difficult it is to make those yummy butter pastries by hand? When a simple 'gloth' spell would fold the dough 83 times it was possible to make a profit, but now 'gloth' hardly works, and when it does, it usually folds the dough too often and the butter melts, or it doesn't come out the right size, or..." He stops, apparently overwhelmed by the prospect of a world where the pastries have to be hand-made. "Can't you do anything about this? You're supposed to know all about magic!"

Hoobly of the Guild of Brewers stands, gesturing at the floury baker. "You don't know what trouble is! Lately, what comes out of the vats, like as not, is cherry flavored or worse. The last vat, I swear it, tasted as if grues had been bathing in it. It takes magic to turn weird vegetables and water into good Borphee beer. Well, without magic, there isn't going to be any beer!" This statement has a profound effect on portions of the crowd. You can hear rumblings from the back concerning Enchanters. The word "traitors" rises out of nowhere. Your fellow Enchanters are looking at one another nervously.

Then everyone except for you is abruptly turned into some variety of small amphibian, and your adventure truly begins. Ah, well, what did a committee hearing ever accomplish anyway?

You find yourself pursuing a mysterious antagonist — obviously the source of the magical disruptions — through a whole series of interlinked scenic vignettes, most no more than a few rooms in size (thus the lack of the need for mapping), which you reach by casting the Blorple spell (“explore an object’s mystic connections”) on a series of magical cubes you find. The acquisition of more of these cubes, representing as each does the next waypoint in a grand chase across time and space, turns out to be the main goal of most of the scenes you visit.

While certain aspects of Spellbreaker, like a group of wandering boulders on which you have to hitch a ride at one point, suggest that Lebling may have been reading Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels (as it happens, a subject we’ll get to very soon in another article), the most marked literary influence is Ursula Le Guin’s classic fantasy A Wizard of Earthsea, a great favorite of Lebling’s. Like the young wizard Ged, the protagonist of Spellbreaker realizes at the story’s climax that the shadowy being against whom he has been struggling is in fact a shadow of himself. The discovery is followed by Spellbreaker‘s ambiguously profound coda.

The shadow, now as solid as a real person, performs a back flip into the tesseract. "No!" It screams. "Stop! Fool, you've destroyed me! You've destroyed magic itself! All my lovely plans!" Now glowing as brightly as the construction it made, the figure approaches the center. It grows smaller and smaller, and just before it disappears, the hypercube vanishes with a pop, and the "magic" cube melts in your hand like an ice cube.

You find yourself back in Belwit Square, all the Guildmasters and even Belboz crowding around you. "A new age begins today," says Belboz after hearing your story. "The age of magic is ended, as it must, for as magic can confer absolute power, so it can also produce absolute evil. We may defeat this evil when it appears, but if wizardry builds it anew, we can never ultimately win. The new world will be strange, but in time it will serve us better."

Your score is 600 of a possible 600, in 835 moves. This puts you in the class of Scientist.

As with so much of Brian Moriarty’s best work, Spellbreaker‘s ending makes more mythic than literal sense. It seems our efforts have only led to the end of the Age of Magic and the beginning of the Age of Science. You can read this in many ways — personal and public, negative and positive. You can cast it as the proverbial setting aside of childish things (while hopefully still leaving space for the occasional computer game), marching into a future of adulthood and responsibility with clear eyes. You can cast it in a melancholy light, as the loss of, well, magic in a modern world where everything is already explored and mapped and monitored. Or you can, as I prefer, cast it as the dawning of a better age free of the prejudices and superstitious dependencies of the past. Any way you cast it, to my mind this textual Rorschach test is one of the strongest endings in the Infocom canon; the contrast of “Scientist” with your penultimate title of “Archimage” is bracing and surprising in all the right ways.

That, then, is Spellbreaker, and a thoroughly admirable effort it is. But I couldn’t conclude this article without also describing the great Spellbreaker vs. Mage feud of 1985, an internal struggle so pitched that it still prompts sheepish half-grins and slight discomfort amongst the principal antagonists, Mike Dornbrook and Dave Lebling, today.

Almost from the point he first accepted the assignment to finish out the Enchanter trilogy, Lebling had planned to call his game Mage. It not only gave the names in the trilogy a nice consonance, what with all being synonyms for a wizard or magic user, but also implied a progression of increasing magical potency. When Dornbrook’s marketing people did some impromptu person-on-the-street questioning, however, they discovered a dismaying fact: most people had never heard the word “mage” and had no idea how to pronounce it. Most opted for either something that rhymed with “badge” or a vaguely French pronunciation, like the second syllable in “garage.” The package designers were also concerned that the name was just too short and bland-looking, that it wouldn’t “pop” like it needed to on a store shelf. So Dornbrook went back to Lebling to tell him that the name just wasn’t going to work; they’d have to come up with another.

This in itself wasn’t all that unusual; games like Wishbringer, which had the perfect name almost from the beginning and kept it until release, were more the exception than the rule at Infocom. Most of the time the Imp responsible realized that his title was less than ideal and was willing to accept alternatives. That, however, was not the case this time. Lebling got his back up, determined that his game would be Mage and only Mage. Dornbrook got his up in response, and a lengthy struggle ensued. The other Imps and the other marketers fell in behind their respective standard bearers, leaving poor Jon Palace caught in the middle trying to broker some sort of compromise for a situation which didn’t really seem to allow for one; after all, in the end the game would either be called Mage or it wouldn’t.

From the perspective of today, the most interesting thing about this whole situation is the fact that so many people didn’t know the word “mage” in the first place. It really serves to highlight how much fantasy (nerd?) culture has penetrated the mainstream in this post-Peter Jackson, post-Harry Potter, post-World of Warcraft world in which we live. In 1985 Lebling’s strongest argument against marketing’s findings, one which strikes me as entirely reasonable, was that Dornbrook and company had simply been polling the wrong people. While the average person on the street may not have known the word “mage,” those likely to be interested in the third game of a fantasy trilogy explicitly pitched toward Infocom’s most hardcore fans almost certainly did. As for the aforementioned person on the street, she wasn’t likely to buy the game no matter what it was called.

As usual with such spats inside any relationship, there was actually a lot going on here beyond the ostensible bone of contention. Dornbrook had been frustrated for years already by what he saw as the Imps’ refusal to properly leverage the most valuable marketing tool at their disposal, the name Zork itself. Back in the company’s earliest days, when he had founded the Zork Users Group, he had simply assumed that Infocom would stamp the Zork brand on everything that would hold still for long enough.

It [the game that became Deadline] would have been Zork: The Mystery, etc. I thought that made sense at the time. We had this incredibly strong brand name. To me they were just going to be Zorks. We were going to own a word like “aspirin.” The name for a text adventure was going to be a Zork, and we were going to own that. But a decision was made while I was in business school and not contributing to the decision-making that we didn’t want to go down that path.

Dornbrook’s frustrations were made worse by 1983’s Enchanter, which everyone had assumed would be Zork IV until very shortly before its release, when Lebling and his coauthor Marc Blank suddenly announced that they didn’t want to be “typecast” by forever doing Zorks. Dornbrook tried fruitlessly to explain that, while it might not make sense that people would buy a game if it was called Zork but not if it was called Enchanter, that was just the way that branding worked. Observing how each game in the new trilogy sold fewer copies than the Zork games had and, even more dismayingly, fewer copies than its immediate predecessor, Dornbrook was soon convinced that the company had sacrificed tens or even hundreds of thousands of sales to the Imps’ effete artistic sensibilities.

I felt that marketing needed to be a little more respected, and if we had a strong feeling about something they [the Imps] shouldn’t just… I mean, the game developers, I got along very well and respected them, but there was a bit of, um… they were a little too full of themselves. A little too self-important. A little too, at times, megalomaniacal. Okay, that’s too strong a word… but it was frustrating sometimes from just a business standpoint. They kind of positioned themselves as, “We’re above all that! We’re artists!” Sometimes it seemed a little too precious.

As the 1980s wore on, Dornbrook couldn’t help but compare Infocom to competitors like Origin Systems and Sierra, who unabashedly milked their flagship brands — Ultima and King’s Quest respectively — for all they were worth via an open-ended series of numbered sequels, and, not coincidentally he believed, by mid-decade and beyond were selling far more games than Infocom. Dornbrook now saw a convenient opportunity to force through a mid-course correction of sorts. He thought about how Enchanter still had the internal inventory code of “Z4” at Infocom, Sorcerer and Lebling’s new game “Z5” and “Z6” respectively.

There was a time later on when I came back and seriously suggested, when there was the big fight over Mage vs. Spellbreaker, why don’t we just call it Zork VI? “You can’t do that! What about Zork IV and V?” I said, “Won’t that create a whole bunch of great questions? Maybe it will help sell Enchanter and Sorcerer if they finally realize, oh, those were Zork IV and V.” I never won that argument.

So Dornbrook still didn’t get his Zork; Lebling, who admits he was “terribly exercised” over the whole situation, wasn’t going to allow him that satisfaction, although he does concede it to have been an interesting idea worth considering today. But Lebling didn’t get his Mage either. The game shipped as another suggestion of Dornbrook’s people, Spellbreaker — not a half-bad name in my book, for what it’s worth. Lebling, however, wasn’t pleased at all, and indulged in an uncharacteristic final bit of sour-grapesmanship by sneaking a new routine into the final version that caused it to call itself Mage in the title line about one time out of every hundred.

The worrisome downward sales trend that Dornbrook had spotted wasn’t halted by Spellbreaker. Like its predecessor A Mind Forever Voyaging, it sold only about 30,000 copies, making these latest games the two least successful Infocom had so far released. There were obvious reasons for the low sales of each attributable to it specifically rather than Infocom’s position in the market as a whole — A Mind Forever Voyaging was highly experimental and required a fairly powerful computer to run, while Spellbreaker was unlikely to appeal to anyone who wasn’t already a hardcore Infocom fan who had already played Enchanter and Sorcerer — but, well, let’s just say that Dornbrook and everyone else had good reason to be worried.

But such external concerns needn’t distract us from playing and enjoying Spellbreaker today. It’s certainly not the place to start with Infocom, but when you’re ready for it it will be there waiting for you. It really is a masterful piece of game design, and even offers some lovely writing as well. It just might be Dave Lebling’s finest hour — and considering that Lebling also co-wrote Enchanter (and considering how much this critic loves that game as well) that’s really saying something.

(Most of the information here is, again, drawn from Jason Scott’s Get Lamp interview archives. The insight about A Wizard of Earthsea‘s influence on Spellbreaker I owe to an eight-year-old email exchange with Graham Nelson — to whom I also owe thanks just for getting me to read that book.)