We approached games as immersive simulations. We wanted to build game environments that reacted to player’s decisions, that behaved in natural ways, and where players had more verbs than simply “shoot.” DOOM was not an influence on System Shock. We were trying something more difficult and nuanced, [although] we still had a lot of respect for the simplicity and focus of [the id] games. There was, to my recollection, a vague sense of fatalism about the parallel tracks the two companies were taking, since it was clear early on that id’s approach, which needed much less player education and which ran on adrenaline rather than planning and immersion, was more likely to be commercially successful. But we all believed very strongly in Looking Glass’s direction, and were proud that we were taking games to a more cerebral and story-rich place.

— Dorian Hart

We hope that our toiling now to make things work when it is still very hard to do effectively will mean that when it is easier to do, we can concentrate on the parts of the game that are less ephemeral than polygons per second, and distinguish ourselves by designing detailed and immersive environments which are about more than just the technology.

— Doug Church

In late 1992, two separate studios began working on two separate games whose descriptions sound weirdly identical to one another. Each was to make you the last human survivor on a besieged space station. You would roam its corridors in real time in an embodied first-person view; both studios prided themselves on their cutting-edge 3D graphics technology. As you explored, you would have to kill or be killed by the monsters swarming the complex. Yet wresting back control of the station would demand more than raw firepower: in the end, you would have to outwit the malevolent intelligence behind it all. Both games were envisioned as unprecedentedly rich interactive experiences, as a visceral new way of living through an interactive story.

But in the months that followed, these two projects that had started out so conceptually similar diverged dramatically. The team that was working on DOOM at id Software down in Dallas, Texas, decided that all of the elaborate plotting and puzzles were just getting in the way of the simpler, purer joys of blowing away demons with a shotgun. Lead programmer John Carmack summed up id’s attitude: “Story in a game is like story in a porn movie. It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” id discovered that they weren’t really interested in making an immersive virtual world; they were interested in making an exciting game, one whose “gameyness” they felt no shame in foregrounding.

Meanwhile the folks at the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based studio Looking Glass Technologies stuck obstinately to their original vision. They made exactly the uncompromising experience they had first discussed, refusing to trade psychological horror in for cheaper thrills. System Shock would demand far more of its players than DOOM, but would prove in its way an even more rewarding game for those willing to follow it down the moody, disturbing path it unfolded.

It was in this moment, then, that the differences between id and Looking Glass, the yin and the yang of 1990s 3D-graphics pioneers, became abundantly clear.

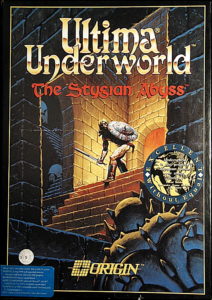

Looking Glass arrived at their crossroads moment just as they were completing their second game, Ultima Underworld II. Both it and its predecessor were first-person fantasy dungeon crawls set in and around Britannia, the venerable world of the Ultima CRPG series to which their games served as spinoffs. And both were very successful, so much so that they almost overshadowed Ultima VII, the latest entry in the mainline series. Looking Glass’s publisher Origin Systems would have been happy to let them continue making games in this vein for as long as their customers kept buying them.

But Looking Glass, evincing the creative restlessness that would define them throughout their existence, was ready to move on to other challenges. In the months immediately after Ultima Underworld II was completed, the studio’s head Paul Neurath allowed his charges to start three wildly diverse projects on the back of the proceeds from the Underworld games, projects which were unified only by their heavy reliance on 3D graphics. One was a game of squad-level tactical combat called Terra Nova, another a civilian flight simulator called Flight Unlimited. And the third — actually, the first of the trio to be officially initiated — was System Shock.

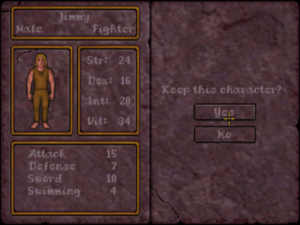

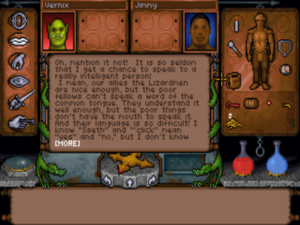

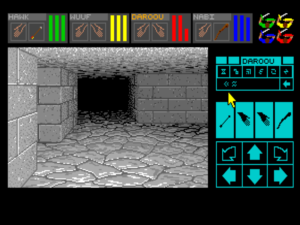

Doug Church, the driving creative force behind Ultima Underworld, longed to create seamless interactive experiences, where you didn’t so much play a game as enter into its world. The Underworld games had been a big step in that direction within the constraints of the CRPG form, thanks to their first-person, free-scrolling perspective, their real-time gameplay, and, not least, the way they cast you in the role of a single embodied dungeon delver rather than that of the disembodied manager of a whole party of them. But Church believed that there was still too much that pulled you out of their worlds. Although the games were played entirely from a single screen, which itself put them far ahead of most CRPGs in terms of immediacy, you were still switching constantly from mode to mode within that screen. “I felt that Underworld was sort of [four] different games that you played in parallel,” says Church. “There was the stats-based game with the experience points, the inventory-collecting-and-managing game, the 3D-moving-around game, and there was the talking game — the conversation-branch game.” What had seemed so fresh and innovative a couple of years earlier now struck Church as clunky.

Ironically, much of what he was objecting to is inherent to the CRPG form itself. Aficionados of the genre find it endlessly enjoyable to pore over their characters’ statistics at level-up time, to min-max their equipment and skills. And this is fine: the genre is as legitimate as any other. Yet Church himself found its cool intellectual appeal, derived from its antecedents on the tabletop which had no choice but to reveal all of their numbers to their players, to be antithetical to the sort of game that he wanted to make next:

In Underworld, there was all this dice rolling going on off-screen basically, and I’ve always felt it was kind of silly. Dice were invented as a way to simulate swinging your sword to see if you hit or miss. So everyone builds computer games where you move around in 3D and swing your sword and hit or miss, and then if you hit you roll some dice to simulate swinging a sword to decide if you hit or miss. How is anyone supposed to understand unless you print the numbers? Which is why, I think, most of the games that really try to be hardcore RPGs actually print out, “You rolled a 17!” In [the tabletop game of] Warhammer when you get a five-percent increase and the next time you roll your attack you make it by three percent, you’re all excited because you know that five-percent increase is why you hit. In a computer game you have absolutely no idea. And so we really wanted to get rid of all that super opaque, “I have no idea what’s going on” stuff. We wanted to make it so you can watch and play and it’s all happening.

So, there would be no numbers in his next game — no character levels, no character statistics, not even quantifiable hit points. There would just be you, right there in the world, without any intervening layers of abstraction.

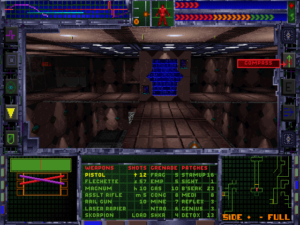

Over the course of extensive discussions involving Doug Church himself, Paul Neurath, Looking Glass designer and writer Austin Grossman, and their Origin Systems producer Warren Spector, it was decided to make a first-person science-fiction game with distinct cyberpunk overtones, pitting you against an insane computer known as SHODAN. Cyberpunk was anything but a novelty in the games of the 1990s, a time when authors like William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Neal Stephenson all occupied prominent places on the genre-fiction bestseller charts and the game developers who read their novels rushed to bring their visions to life on monitor screens. Still, cyberpunk would suit Looking Glass’s purposes unusually perfectly by presenting a credible explanation for the diegetic interface Church was envisioning. You would play a character with a neural implant that let you “see” a heads-up display sporting a life bar for yourself, an energy bar for your weapons and other hardware, etc. — all of it a part of the virtual world rather than external to it. When you switched between “modes,” such as when bringing up the auto-map or your inventory display, it would be the embodied you who did so in the virtual world, not that other you who sat in front of the computer telling a puppet what to do next.

System Shock‘s commitment to its diegetic presentation is complete. As you discover new software and gadgets, they’re added to the heads-up display provided by your in-world neural implant. This serves the same purpose that leveling up did in Ultima Underworld, but in a more natural, realistic way.

Dissatisfied with what he saw as the immersion-killing conversation trees of Ultima Underworld, Church decided to get rid of two-way conversation altogether. When the game began, there would be enticing signs that other humans were still alive somewhere on the space station, but you would be consistently too late to reach them; you would encounter them only as the zombies SHODAN turned them into after death. Of course, all of this too was highly derivative, and on multiple levels at that. Science-fiction fans had been watching their heroes take down out-of-control computers since the original Star Trek television series if not before; “I don’t think if you wrote the novel [of System Shock] it would fly off the shelves,” admits Church. Likewise, computer games had been contriving ways to place you in deserted worlds, or in worlds inhabited only by simple-minded creatures out for your blood, for as long as said games had existed, always in order to avoid the complications of character interaction; the stately isolation of the mega-hit adventure game Myst was only the most recent notable example of the longstanding tradition at the time System Shock was in development.

But often it’s not what you do in any form of media, it’s how well you do it. And System Shock does what it sets out to do very, very well indeed. It tells a story of considerable complexity and nuance through the artifacts you find lying about as you explore the station and the emails you receive from time to time, allowing you to piece it all together for yourself in nonlinear fashion. “We wanted to make the plot and story development of System Shock be an exploration as well,” says Church, “and that’s why it’s all in the logs and data, so then it’s very tied into movement through the spaces.”

Reading a log entry. The story is conveyed entirely through epistolary means like these, along with occasional direct addresses from SHODAN herself that come booming through the station’s public-address system.

Moving through said spaces, picking up bits and pieces of the horrible events which have unfolded there, quickly becomes highly unnerving. The sense of embodied realism that clings to every aspect of the game is key to the sense of genuine, oppressive fear it creates in its player. Tellingly, Looking Glass liked to call System Shock a “simulation,” even though it simulates nothing that has ever existed in the real world. The word is rather shorthand for its absolute commitment to the truth — fictional truth, yes, but truth nevertheless — of the world it drops you into.

Story is very important to System Shock — and yet, in marked contrast to works in the more traditionally narrative-oriented genre of the adventure game, its engine also offers heaps and heaps of emergent possibility as you move through the station discovering what has gone wrong here and, finally, how you might be able to fix it. “It wasn’t just, ‘Go do this sequence of four things,'” says Church. “It was, ‘Well, there are going to be twelve cameras here and you gotta take out eight of them. Figure it out.’ We [also] gave you the option [of saying], ‘I don’t want to fight that guy. Okay, maybe I can find another way…'”

Thus System Shock manages the neat trick of combining a compelling narrative with a completely coherent environment that never reduces you to choosing from a menu of options, one where just about any solution for any given problem that seems like it ought to work really does work. Just how did Looking Glass achieve this when so many others before and since have failed, or been so daunted by the challenges involved that they never even bothered to try? They did so by combining technical excellence with an aesthetic sophistication to which few of their peers could even imagine aspiring.

Just as the 3D engine that powers Ultima Underworld is more advanced than the pseudo-3D of id’s contemporaneous Wolfenstein 3D, the System Shock engine outdoes DOOM in a number of important respects. The enormous environments of System Shock curve over and under and around one another, complete with sloping floors everywhere; lighting is realistically simulated; you can jump and crouch and look up and down and lean around corners; you can take advantage of its surprisingly advanced level of physics simulation in countless ingenious ways. System Shock even boasts perspective-correct texture mapping, a huge advance over Ultima Underworld, and no easy thing to combine with the aforementioned slopes.

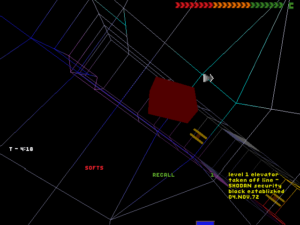

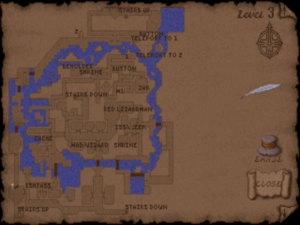

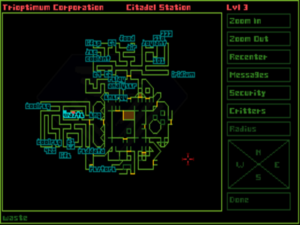

Each of the ten “levels” of System Shock is really multiple levels in the physical sense, as the corridors often curve over and under one another. Just as in Ultima Underworld, you can annotate the auto-map for yourself. But even with this aid, just finding your way around in these huge, confusing spaces can be a challenge in itself.

That said, it’s also abundantly true that a more advanced engine doesn’t automatically make for a better game. Any such comparison must always carry an implied addendum: better for whom? Certainly DOOM succeeded beautifully in realizing its makers’ ambitions, even as its more streamlined engine could run well on many more of the typical computers of the mid-1990s than System Shock‘s could. By no means do the engines’ respective advantages all run one way: in addition to being much faster than the System Shock engine, the DOOM engine allows rooms of arbitrary sizes and non-orthogonal walls, neither of which is true of its counterpart from Looking Glass.

In the end, System Shock wants to be a very different experience than DOOM, catering to a different style of play, and its own engine is designed to allow it to realize its own ambitions. It demands a more careful approach from its player, where you must constantly use light and shadow, walls and obstacles, to aid you in your desperate struggle. For you are not a superhuman outer-space marine in System Shock; you’re just, well, you, scared and alone in a space station filled with rampaging monsters.

A fine example of the lengths to which Looking Glass’s technologists were willing to go in the service of immersion is provided by the mini-games you can play. Inspired by, of all things, the similarly plot-irrelevant mini-games found in the LucasArts graphic adventure Sam and Max Hit the Road, they contribute much more to the fiction in this case than in that other one. As with everything in System Shock, the mini-games are not external to the world of the main game. It’s rather you playing them through your neural implant right there in the world; it’s you who cowers in a safe corner somewhere, trying to soothe your soul with a quick session of Breakout or Missile Command. You get the chance to collect more and better games as you infiltrate the station’s computer network using the cyberspace jacks you find scattered about — a reward of sorts for a forlorn hacker trying to survive against an all-powerful entity and her horrifying minions.

Sean Barret, a programmer who came to Looking Glass and to the System Shock project well into the game’s development, implemented the most elaborate by far of the mini-games, a gentle satire of Origin Systems’s Wing Commander that goes under the name of Wing 0. The story of its creation is a classic tale of Looking Glass, a demonstration both of the employees’ technical brilliance and their insane levels of commitment to the premises of their games. Newly arrived on the team and wishing to make a good impression, Barrett saw a list of mini-game ideas on a whiteboard; a “Wing Commander clone” was among them. So, he set to work, and some days later presented his creation to his colleagues. They were as shocked as they were delighted; it turned out that the Wing Commander clone had been a joke rather than a serious proposal. In the end, however, System Shock got its very own Wing Commander after all.

Still, there were many other technically excellent and crazily dedicated games studios in the 1990s, just as there are today. What truly set Looking Glass apart was their interest in combining the one sort of intelligence with another kind that has not always been in quite so great a supply in the games industry.

As Looking Glass grew, Paul Neurath brought some very atypical characters into the fold. Already in late 1991, he placed an advertisement in the Boston Globe for a writer with an English degree. He eventually hired Austin Grossman, who would do a masterful job of scattering the puzzle pieces of Doug Church’s story outline around the System Shock space station. There soon followed another writer with an English degree, this one by the name of Dorian Hart, who would construct some of the station’s more devious internal spaces using the flair for drama which he had picked up from all of the books he had read. He was, as he puts it, “a liberal-arts nobody with no coding skills or direct industry experience, thrown onto arguably the most accomplished and leading-edge videogame production team ever assembled. It’s hard to explain how unlikely that was, and how fish-out-of-water I felt.” Nevertheless, there he was — and System Shock was all the better for his presence.

Another, even more unlikely set of game developers arrived in the persons of Greg LoPiccolo and Eric and Terri Brosius, all members of a popular Boston rock band known as Tribe, who had been signed to a major label amidst the Nirvana-fueled indie-rock boom of the early 1990s, only to see the two albums they recorded fail to duplicate their local success on a national scale. They were facing a decidedly uncertain future when Doug Church and Dan Schmidt — the latter being another Looking Glass programmer, designer, and writer — showed up in the audience at a Tribe show. They loved the band’s angular, foreboding songs and arrangements, they explained afterward, and wanted to know if they’d be interested in doing the music for a science-fiction computer game that would have much the same atmosphere. Three members of the band quickly agreed, despite knowing next to nothing about computers or the games they played. “Being young, not knowing what would happen next, that was part of the magic,” remembers Eric Brosius. “We were willing to learn because it was just an exciting time.”

Terri Brosius became the voice of SHODAN, a role that fell to her by default: artificial intelligences in science fiction typically spoke in a female voice, and she was the only woman to be found among the Looking Glass creative staff. But however she got the part, she most definitely made it her own. She laughs that “people tend to get freaked out” when they hear her speak today in real life. And small wonder: her glitchy voice ringing through the empty corridors of the station, dripping with sarcastic malice, is one of the indelible memories that every player of System Shock takes away with her. Simply put, SHODAN creeps you the hell out. “You had a recurring, consistent, palpable enemy who mattered to you,” notes Doug Church — all thanks to Austin Grossman’s SHODAN script and Terri Brosius’s unforgettable portrayal of her.

As I think about the combination of technical excellence and aesthetic sophistication that was Looking Glass, I find one metaphor all but unavoidable: that of Looking Glass as the Infocom of the 1990s. Certainly Infocom, their predecessors of the previous decade on the Boston-area game-development scene, evinced much the same combination — the same thoroughgoing commitment to excellence and innovation in all of their forms — during their own heyday. If the 3D-graphics engines of Looking Glass seem a long way from the text and parsers of Infocom, let that merely be a sign of just how much gaming itself had changed in a short span of time. Even when we turn to more plebeian matters, there are connections to be found beyond a shared zip code. Both studios were intimately bound up with MIT, sharing in the ideas, personnel, and, perhaps most of all, the culture of the university; both had their offices on the same block of CambridgePark Drive; two of Looking Glass’s programmers, Dan Schmidt and Sean Barrett, later wrote well-received textual interactive fictions of their own. The metaphor isn’t ironclad by any means; Legend Entertainment, founded as it was by former Infocom author Bob Bates and employing the talents of Steve Meretzky, is another, more traditionalist answer to the question of the Infocom of the 1990s. Still, the metaphor does do much to highlight the nature of Looking Glass’s achievements, and their importance to the emerging art form of interactive narrative. Few if any studios were as determined to advance that art form as these two were.

But Looking Glass’s ambitions could occasionally outrun even their impressive abilities to implement them, just as could Infocom’s at times. In System Shock, this overreach comes in the form of the sequences that begin when you utilize one of those aforementioned cyberspace jacks that you find scattered about the station. System Shock‘s cyberspace is an unattractive, unwelcoming place — and not in a good way. It’s plagued by clunky controls and graphics that manage to be both too minimalist and too garish, that are in fact almost impossible to make head or tail of. The whole thing is more frustrating than fun, not a patch on the cyberspace sequences to be found in Interplay’s much earlier computer-game adaption of William Gibson’s breakthrough novel Neuromancer. So, it turns out that even the collection of brilliant talent that was assembled at Looking Glass could have one idea too many. Doug Church:

We thought [that] it fit from a conceptual standpoint. You’re a hacker; shouldn’t you hack something? We thought it would be fun to throw in a different movement mode that was more free-form, more action. In retrospect, we probably should have either cut it or spent more time on it. There is some fun stuff in it, but it’s not as polished as it should be. But even so, it was nice because it at least reinforced the idea that you were the hacker, in a totally random, arcadey, broken kind of way. But at least it suggested that you’re something other than a guy with a gun. We were looking at ourselves and saying, “Oh, of course we should have cyberspace! We’re a cyberpunk game, we gotta have cyberspace! Well, what can we do without too much time? What if we do this crazy thing?” Off we went…

By way of compounding the problem, the final confrontation with SHODAN takes place… in cyberspace. This tortuously difficult and thoroughly unfun finale has proven to be too much for many a player, leaving her to walk away on the verge of victory with a terrible last taste of the game lingering in her mouth.

Luckily, it’s possible to work around even this weakness to a large extent, thanks to another of the generous affordances which Looking Glass built into the game. You can decide for yourself how complex and thus how difficult you wish the game to be along four different axes: Combat (the part of the game that is most like DOOM); Mission (the non-combat tasks you have to accomplish to free the station from SHODAN’s grip); Puzzle (the occasional spatial puzzles that crop up when you try to jigger a lock or the like); and Cyber (the cyberspace implementation). All of these can be set to a value between zero and three, allowing you to play System Shock as anything from a straight-up shooter where all you have to do is run and gun to an unusually immersive and emergent pure adventure game populated only by “feeble” enemies who “never attack first.” The default experience sees all of these values set at two, and this is indeed the optimal choice in my opinion for those who don’t have a complete aversion to any one of the game’s aspects — with one exception: I would recommend setting Cyber to one or even zero in order to save yourself at lot of pain, especially at the very end. (The ultimate challenge for System Shock veterans, on the other hand, comes by setting the Mission value to three; this imposes a time limit on the whole game of about seven hours.)

System Shock was released in late 1994, almost two full years after Ultima Underworld II, Looking Glass’s last game. It sold acceptably but not spectacularly well for a studio that was already becoming well-acquainted with the financial worries that would continue to dog them for the rest of their existence. Reviews were quite positive, yet many of the authors of same seemed barely to have noticed the game’s subtler qualities, choosing to lump it in instead with the so-called “DOOM clones” that were beginning to flood the market by this point, almost a year after the original DOOM‘s release. (One advantage of id Software’s more limited ambitions for their game was the fact that it was finished much, much quicker than System Shock; in fact, a DOOM II was already on store shelves by the time System Shock made it there.)

Although everyone at Looking Glass took the high road when asked about the DOOM connection, the press and public’s tendency to diminish their own accomplishment in 3D virtual-world-building had to rankle at some level; former employees insist to this day that DOOM had no influence whatsoever on their own creation, that System Shock would have turned out the same even had DOOM never existed. The fact is, Looking Glass’s own claim to the title of 3D-graphics pioneers is every bit as valid as that of id, and their System Shock engine actually was, as we’ve seen, more advanced than that of DOOM in a number of ways. No games studio in history has ever deserved less to be treated as imitators rather than innovators.

Alas, mainstream appreciation would be tough to come by throughout the remaining years of Looking Glass’s existence, just as it had sometimes been for Infocom before them. A market that favored the direct, visceral pleasures of id’s DOOM and, soon, Quake didn’t seem to know quite what to do with Looking Glass’s more nuanced 3D worlds. And so, yet again as with Infocom, it would not be until after Looking Glass was no more that the world of gaming would come to fully appreciate everything they had achieved. When asked pointedly about the sales charts which his games so consistently failed to top, Doug Church showed wisdom beyond his years in insisting that the important thing was just to earn enough back to make the next game.

id did a great job with [DOOM]. And more power to them. I think you want to do things that connect with the market and you want to do things that people like and you want to do things that get seen. But you also want to do things you actually believe in and you personally want to do. Hey, if you’re going to work twenty hours a day and not get paid much money, you might as well do something you like. We were building the games we were interested in; we had that luxury. We didn’t have spectacular success and a huge win, but we had enough success that we got to do some more. And at some level, at least for me, sure, I’d love to have huge, huge success. But if I get to do another game, that’s pretty hard to complain about.

Today, free of the vicissitudes of an inhospitable marketplace, System Shock more than speaks for itself. Few games, past or present, combine so many diverse ideas into such a worthy whole, and few demonstrate such uncompromising commitment to their premise and their fiction. In a catalog filled with remarkable achievements, System Shock still stands out as one of Looking Glass’s most remarkable games of all, an example of what magical things can happen when technical wizardry is placed in the service of real aesthetic sophistication. By all means, go play it now if you haven’t already. Or, perhaps better said, go live it now.

(Sources: the books Game Design Theory and Practice, second edition, by Richard Rouse III and System Shock: Strategies and Secrets by Bernie Yee; Origin’s official System Shock hint book; Origin’s internal newsletter Point of Origin from June 3 1994, November 23 1994, January 13 1995, February 10 1995, March 14 1995, and May 5 1995; Electronic Entertainment of December 1994; Computer Gaming World of December 1994; Next Generation of February 1995; Game Developer of April/May 1995. Online sources include “Ahead of Its Time: The History of Looking Glass” and “From Looking Glass to Harmonix: The Tribe,” both by Mike Mahardy of Polygon. Most of all, huge thanks to Dorian Hart, Sean Barrett, and Dan Schmidt for talking with me about their time at Looking Glass.

System Shock is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)