Earlier this year, I reached out to Graham Nelson, the most important single technical architect of interactive fiction’s last three decades, to open a dialog about his early life and work. I was rewarded with a rich and enjoyable correspondence. But when the time came to write this article based on it, I found myself on the horns of a dilemma. The problem was not, as it too often is, that I lacked for material to flesh out his personal story. It was rather that Graham had told his own story so well that I didn’t know what I could possibly add to it. I saw little point in paraphrasing what Graham wrote in my own words, trampling all over his spry English irony with my clumsy Americanisms. In the end, I decided not to try.

So, today I present to you Graham Nelson’s story, told as only he can tell it. It’s a rare treat given that Graham is, like so many people of real accomplishment, usually reluctant to speak at any length about himself. I’ll just offer a couple of contextual notes before he begins. The “Inform” to which Graham eventually refers is a specialized text-adventure programming language by that name targeting the Z-Machine (and much later a newer virtual machine known as Glulx which has finally come to supersede Infocom’s venerable creation); Inform has been the most popular tool of its type through the last quarter-century. And Curses is the first full-fledged game ever written with Inform, a puzzly yet eminently literary time-traveling epic which took the huddled, beleaguered text-adventure diehards by storm upon its release in 1993, giving them new hope for their beloved form’s future and inspiring many of them to think of making their own games — using Inform more often than not. In the third and final article of this series on the roots of the Interactive Fiction Renaissance, I’ll examine both of these seminal artifacts in depth with the detachment of a third party, trying to place them in their proper historical context for you. For today, though, I give you Graham Nelson unfiltered to tell you his story of how they — and he — came to be…

I was born in 1968, so I’m coeval with The White Album and Apollo 8. I was born in Chelmsford, in Essex, and grew up mainly in Great Baddow, a quiet suburban village. There were arable farms on one side, where in those days the stubble of the wheat would still be burned off once a year. (In fact, I see that the Wikipedia page for “stubble burning” features a photo from the flat countryside of Essex, taken in 1986. The practice is banned now.) My street, Hollywood Close, had been built in the early 1960s on what used to be Rothman’s Farm. The last trees were still being cut down when I was young, though that was mainly because of Dutch Elm Disease. The houses having been sold all at once, to young families of a similar age, my street was full of seven-year olds when I was seven, and full of fifteen-year olds when I was fifteen. I went to local schools, never more than walking distance away. My primary school, Rothman’s Junior, was built on another field of the same farm, in fact.

My father Peter was an electronics engineer at English Electric Valve. My mother Christine — always “Chris” — was a clerical civil servant before she had me, at the National Assistance Board, which we would call social security today. In those days, women left work when they had a child, which is exactly what she did when she had me and my brother. But later on she trained as a personal assistant, learning Pitman shorthand, which I never picked up, and also typing, which I sort of did: I am a two-fingered typist to this day, but unusually fast at it. I did try the proper technique, but on our home typewriter, my little finger just wasn’t strong enough to strike an “A”. Or perhaps I saw no reason to learn how other people did things.

My parents had met in school in Gosport, a naval village opposite Portsmouth, on the south coast of England. As a result, both sides of my family were in the same town; indeed, we were the eccentric ones, having moved away to Essex. My many aunts, uncles, second cousins, and so on were almost all still in Portsmouth, and we would stay there for every holiday or school break. In effect, it was a second home. Though I didn’t know him for long, a formative influence was my mother’s father Albert, a navy regular who became a postman in civilian life. He was ship’s cook on HMS Belfast during the Second World War; my one successful poem (in the sense of being reprinted, which is the acid test for poems) is in his memory.

None of these people had any higher education at all. I would be the first to go to a university, though my father did the correspondence-course Open University degree in the 1970s, and my mother went to any number of evening classes. (She ended up with a ridiculous number of O-levels, rather the way that some Scouts go on collecting badges until their arms are completely covered.) They both came from genuinely poor backgrounds, where you grew a lot of your own food, and had to make and mend. You didn’t buy books, you borrowed them from the library — though my grandmother did have the Pears Cyclopaedia for 1938 and a dictionary for crosswords. But I didn’t grow up in any way that could be called deprived. My father made a solid middle-class income at a time when that could keep a family of four in a house of their own and run a car. He wasn’t a top-bracket professional, able to sign passport applications as a character reference, like a doctor or a lawyer, but he was definitely white-collar staff, not blue-collar. Yes, he worked in a factory, but in the R&D lab at one end. This is not a Bruce Springsteen song. He would not have known what to do with a six pack of beer.

My brother Toby, who later became a professional computer programmer working at Electronic Arts and other places, was two years younger than me, which meant he passed through school with teachers expecting him to be like me, which he both is and isn’t. He’s my only sibling, though I now also have a brother-in-law and sister-in-law. “Graham” and “Toby” are both definitely unusual names in England in our generation, which is the sort of thing that annoys you as a child, but is then usefully distinctive in later life. At least “Graham” is unabbreviable, for which I have always been grateful.

The local education authority would have expected me to pass the eleven-plus exam, and move up the social ladder to King Edward VI Grammar School, the best in the area by far. But my parents, who believed in universal education, chose not to enter me. So at eleven and a half, I began at Great Baddow Comprehensive School. I didn’t regret this then, and don’t now. I had some fine teachers, and though I was an oddity there, I would have been an oddity anywhere. Besides, I had plenty of friends; it wasn’t the social snake-pit which American high schools always seem to be on television.

Until around 1980, there were no commercial home computers in the UK, which was consistently a couple of years behind the United States in that respect. But my father Peter was also an electronics hobbyist. Practical Electronics magazine tended to be around the house, and even American magazines like Byte, on occasion; I had a copy of the legendary Smalltalk number of Byte, with its famous hot-air-balloon cover. But the gap between these magazines — and the book in my school library about Unix — and reality was enormous. All we had in the house was a breadboard and some TTL chips. Remarkably, my father nevertheless built a computer the size of a typewriter. It had no persistent storage; you had to key in opcodes in hex with a numeric keypad. But it worked. It was a mechanism with no moving parts. It’s hard to explain now how almost alchemical that seemed. He would give a little my-team-has-won-again cheer from his armchair whenever the BBC show Tomorrow’s World used the words “integrated circuits”. (I think this was a little before the term “microchips” came into common usage, or possibly the BBC simply thought it a vulgar colloquialism. They were more old-school back then.)

Until I was twelve years old, then, computing was something done on mainframes – or at any rate “minis” like the DEC VAX, running payroll for medium-sized companies. Schools never had these, or anything else for that matter. In the ordinary way of things, I would never have seen or touched a real computer. But I did, on just a few tantalising occasions.

Great Baddow was not really a tech town, but it was where Marconi had set up, and so there were avionics businesses, such as the one my father worked for, English Electric Valve. Because of that, a rising industry figure named Ian Young lived in our street. His two boys were just about the same age as me and my brother, and he and his wife Gill were good friends of my parents — I caught up with them at my parents’ sixtieth wedding anniversary only a few weeks ago. Ian soon relocated to Reading as an executive climbing the ranks of Digital Equipment Corporation, then the world’s number two computer company after IBM, but our families kept in touch. A couple of times each year my brother and I would go off to spend a week with the Youngs during the school holidays. This is beginning to sound like a Narnia book, and in a way it was a little like that. Ian would sportingly take us four boys to DEC’s headquarters — in particular, to the darkened rooms where the programmers worked, in an industrial space shared with a biscuit factory. (Another fun thing about the Youngs was that they always had plenty of chocolate-coated Club biscuits from factory surplus.) We would sit at a VT-220 terminal with a fluorescent green screen and play the DECUS user group’s collection of games for the VAX. These were entirely textual, though a few, like chess or Star Trek, rendered a board using ASCII art. Most of these games were flimsy nothings: a boxing simulator, I remember, a Towers of Hanoi demo, and so on. But the exception was Crowther and Woods’s Adventure, which I played less than a year after Don Woods’s canonical first version was circulated by DECUS. Adventure was like nothing else, and had a depth and an ability to entrance which is hard to overstate. There was no such thing as saving the game — or if there was, we didn’t know about it. We simply remembered that you had to unlock the grating, and that the rusty iron rod would… and so on. Our sessions almost invariably ended in one of the two unforgiving mazes. But that was somehow not an unsatisfying thing. It seemed like something you were exploring, not something you were trying to win.

It was, of course, maddening to be hooked on a game you could play perhaps once every six months. I got my first actual computer in 1980, for my twelfth birthday: an Acorn Atom. I had the circuit diagram on my wall; it was the first and last computer I’ve ever owned which I understood the physical workings of. My father assembled it from the kit form. This was £50 cheaper — not a trivial sum in those days — and was also rather satisfying for him, both because it was a lovely bit of craftsmanship to put together (involving two weekends of non-stop soldering), and also because he was never such a hero to his son as when we finally plugged it in and it worked flawlessly. Curious how much of this story appears to be about fathers and sons…

At any rate, I began thinking about implementing “adventures” very early on. This was close to impossible on a computer with 12 K of RAM (and even that only after I slowly expanded it, buying 0.5 K memory chips one at a time from a local hardware store). And yet… I can still remember the epiphany when I realised that you could model the location of an object by storing this in a byte which was either a room number or a special value to mean “being carried”. I think the most feasible creation I came up with was a procedurally-generated game on a squared grid, ten rooms wide by infinity rooms long, where certain rooms were overridden with names and puzzles. It had no title, but was known in my family as “the adventure of Igneous the Dwarf”, after its only real character. My first published game was an imitation of the arcade game Frogger for the Acorn Atom. I made something like £70 in royalties from it, but it really had no interactive-fiction content of any kind.

My first experience of commercial interactive fiction came for the BBC Micro, the big brother of the Acorn Atom; my father being my big brother in this instance, since he bought one in 1981. The Scott Adams line made it onto the BBC Micro, and so did ports of the Cambridge mainframe games, marketed first by Acornsoft and then by Topologika. I thus played some of the canonical Cambridge games quite a while before going to Cambridge. (Cambridge was then the lodestone of the UK computing industry; things like the BBC Micro and the ARM chip are easily overlooked in Cambridge’s history, given the university’s work with gravity, evolution, the electron, etc., but this was not a small deal at the time.) In particular, the most ambitious of the Cambridge games, Acheton, came out from Acornsoft on a disk release, and I played it. This was an extraordinary thing; in the United Kingdom, few computer owners had disk drives, and no more than a handful of BBC Micro games were ever released in that format.

I made something fractionally like a graphical adventure, called Crystal Castle, for the BBC Micro. (In 2000, Toby helpfully, if that’s the word, found the last existing cassette tape of this, digitised it to a WAV file, signal-processed the result, and ended up with about 22 K of program and data. To our astonishment, it ran.) It was written in binary machine code, which thus had no source code. Crystal Castle was nearly published, but the deal ultimately fell through. Superior Software, then the best marque for BBC Micro stuff, exchanged friendly letters with me, and for a while it really did look like it would happen. But I really needed an artist, and a bit more design skill. So, they passed. I imagine they had quite a large slush pile of games on cassette sent in by aspiring coders back then. You should not think of me as a teenage entrepreneur; I was mostly unsuccessful.

I did get two BBC Micro games published in 1984 by a cottage-industry sort of software house somewhere in Essex, run by a local teacher. Anybody who could arrange to duplicate cassette tapes and print inlay cards could be a “software house” in those days, and quite a lot of firms with improvised names (“Aardvark Software”, etc.) were actually people running a mail-order business out of their front rooms. They sold my two games as one, in that they were side A and side B of the same cassette. The games had the somewhat Asimovian names Galaxy’s Edge and Escape from Solaris. I honestly remember little about them, except that Escape from Solaris was a two-handed game. To play, you had to connect two BBC Micros back-to-back with an RS-423 cable, and then you had to type alternate commands. One program would stall while the other was active, but the thing worked. I cannot imagine that these games were any good, but the milieu was that of alien science being indistinguishable from magic. The role-playing game Traveller may have been an influence, I suppose, but my local library had also stocked a great deal of golden-age science fiction, and I had read every last dreg of it. (I hadn’t, at that time, played Starcross, though I’d probably seen Level 9’s Snowball.) I do not still have copies, and I am therefore spared the moral dilemma of whether I should make them publicly available. I did get a piece of fan mail, I remember, by someone who asked if I was a chemist. From this memory, I infer that there were some science-based puzzles.

The Quill-written games weren’t any influence on me, nor really the Magnetic Scrolls ones. The Quill was a ZX Spectrum phenomenon — and the Spectrum came from Acorn’s arch-enemy Sinclair. I think my father regarded it as unsound. It certainly did not have a keyboard designed to the requirement that it survive having a cup of coffee poured through it, as the BBC Micro did. But it did have an enormous amount of RAM — or rather, it didn’t consume all of that precious RAM on screen memory. The way that it avoided this was a distasteful hack, but also a stroke of genius, making the Spectrum a perfect games machine. As a result, those of my friends whose fathers knew anything about computers had BBC Micros, and the rest had Spectrums. It is somehow very English of us to have invented a new class distinction in the 1980s, but I rather think we did. Magnetic Scrolls were a different case, since they were adopting an Infocom-like strategy of releasing for multiple platforms, but they came along later, and always seemed to me to be more style than substance. The Pawn was heavily promoted, but I didn’t care for it.

I really must mention Level 9, though. They wrote 200-room cave adventures – albeit sometimes the cave was a starship – and by dint of some ingenious compression were able to get them out on tape. In particular, I played through to completion all three of the original Level 9 fantasy trilogy: the first being an extended version of the Crowther and Woods Adventure, the second and third being new but in the same style. I still think these good, in some relative sense. Level 9’s version of the Crowther and Woods Adventure, Colossal Adventure, was the first version which I fully explored, so that it still half seems to me like the definitive version. Ironically, none of Level 9’s games had levels in the normal gaming sense.

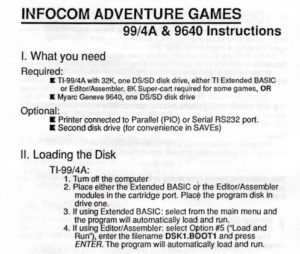

I didn’t play any of Infocom’s games until, I think, 1987. I bought a handful, one at a time, from Harrod’s in Knightsbridge — a department store for the rich and, it would like to imagine, the socially elite. I was neither of those things, but I knew what I wanted. Infocom’s wares were luxury goods, and luxury goods tend to stay on the shelves until they sell. Harrod’s had a modest stock, which almost nobody else in the UK did, though you could find a handful of early Infocom titles such as Suspended for the Commodore 64 if you trawled the more plebeian electronics shops of Tottenham Court Road. The ones I bought were CP/M editions of some of the classic titles of 1983 to 1985: Enchanter, I remember, being the first. These we were able to run on my brother’s computer, which was an Amstrad, a British machine built for word processing, but which — thanks to the cheapness of Alan Sugar, Amstrad’s proprietor, a sort of British version of Commodore’s Jack Tramiel — ran CP/M rather than MS-DOS.

That was just after I had begun as an undergraduate at Cambridge and joined the mainframe there, Phoenix, as a user. Each user had an allocation of “shares”, which governed how much computing time you could have. As the newest kid to arrive, I had ten shares. There were legends of a man in computational chemistry, modelling the Schrödinger equation for polythene, who had something like 10,000. At any rate, ten shares was only just enough to read your email in daytime. To run anything like Dungeon, the IBM port of Zork, you had to sit up at night — which we did, a little. I think Dungeon was the only externally-written game playable on Phoenix; the others were all homegrown, using TSAL, the game assembler written by David Seal and Jonathan Thackray. As I wrote long ago, to me and others who played them those games “are as redolent of late nights in the User Area as the soapy taste of Nestlé’s vending-machine chocolate or floppy, rapidly-yellowing line printer paper.” As I noted earlier, most of them ultimately migrated to Acornsoft and Topologika releases.

But there were other social aspects to Phoenix as well. There was a rudimentary bulletin board called GROGGS (the “General Reverse-Ordered Gossip-Gathering System”) and it was tacitly encouraged by the Phoenix administrators because it stopped people abusing the Suggest program as a noticeboard. (We did not then have access to Usenet.) GROGGS was unusually egalitarian — students and faculty somewhat mingled, which was not typical of Cambridge then. Its undoubted king was Jonathan Partington (JRP1), a young professor who had a generous, playful wit. The Phoenix administrators dreaded his parodies of their official announcements. In his presence, GROGGS was a little like the salon in which the hangers-on of Oscar Wilde would attempt to keep up. Numerous people had a schtick; mine was to mutate my user-name to some version of the Prufrockian “I am not Prince Hamlet”. Commenting on the new Dire Straits album, I would post as “I am not Mark Knopfler”. That sort of thing. Jonathan wrote some of the Cambridge mainframe games. He taught me for a few second-year options.

There was also a form of direct messaging, the “notify” command, and you had the ability to link your filespace to somebody else’s, in effect giving them shared access. At some point Mark Owen and Matthew Richards, inseparable friends at Trinity College, observed that these links turned the users of Phoenix into a directed graph — what we would now call a social network. Mark and Matthew converted the whole mainframe into a sort of adventure game on this basis, in which user filespaces were the rooms, and links were map connections between them. You could store a little text file in your filespace as your own room description. Mark and Matthew’s system was called MEGA, a name chosen as an anagram of GAME. Mark went on to take a PhD in neural networks, back in the days when they didn’t work and were considered a dead end; he eventually wrote a book on signal processing. Matthew, a gifted algebraist and one of the nicest people I have ever known, died of Hodgkin’s disease only a couple of years into his own PhD — the first shock of death close up that most of us had known. The doctors tried everything to keep him alive. There’s no length they won’t go to with a young, strong patient, however cruel.

At any rate, back in the days of MEGA, it occurred to me that more could be done. Rather than storing just a single room description, each user could store a larger blob of content, and we would then have a form of MUD. This system, jointly coded by myself and a CS student called John Croft, was called TERA (I forget why we didn’t go up from MEGA to GIGA — perhaps there already was one?) and its compiler was “teraform”. This is the origin of the “-form” suffix in Inform’s name.

Cambridge mathematics degrees were in four parts: IA, IB, II, and III. Part III was an optional fourth year, which now earns you a master’s, but which for arcane funding reasons didn’t in my day. The Part III people were the aspiring professionals, hoping for a PhD grant at the end of it. Only seven or eight were available, which lent a competitive edge to a social group which was all too competitive already. I was thoroughly settled in Cambridge, living in an old Victorian house off Trumpington Street with four close friends, down by the river meadows. It was a very happy time in my life, and I had absolutely no intention of giving it up. As a geometer, I was hoping to be a research student of Frank Adams, a legendary topologist but a man with an awkward, stand-offish character. I’m now rather glad that this didn’t happen, though I’m sorry about the reason, which was that he died in a car crash. The only possible alternative, the affable Ray Lickorish, was just going on sabbatical. And so I found myself obliged to apply to Oxford instead. I was very fortunate to become the student of Simon Donaldson, only the fifth British mathematician to win the Fields Medal. (He is warmly remembered at St Anne’s College, where I now am, not for the Fields, or the Crafoord Prize, or for being knighted, or winning a $3 million award — not for any of that, but for having been a good Nursery Fellow, looking after the college crèche.) Having opened up a new and, almost at once, a rapidly-moving field of study, Simon was over-extended with collaborators, and I wasn’t often a good use of his time. Picture me as one of those plodding Viennese students Beethoven was obliged to give piano lessons to. But it was a privilege even to be present at an important moment in the history of modern geometry, and in his quietly kind way, Simon was an inspirational leader.

So, although I did find myself a doctoral perch, I had time on my hands — not work time, as I had plenty to do on that front, but social time, since everyone I knew was back in Cambridge. I read a great many books, buying up remaindered Faber literary paperbacks from the Henry Pordes bookshop in Charing Cross Road, London, whenever I was passing through. The plays of Tom Stoppard, Alan Bennett, David Hare; the poems of Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney, Auden, Eliot, and so forth. I wrote a novel, which had to do with two people who worked in a research lab doing unethical things attempting to control chimpanzees. He took the work at face value, she didn’t, or perhaps it was the other way around. By the time I finished, I knew enough to know that it wasn’t any good, but in so far as you become a writer simply by writing, I had become a writer. I then wrote four short stories, and a one-act play called A Church by Daylight (a title which is a tag borrowed from Much Ado About Nothing). This play was thin on plot but had to do with loss. I wasn’t much good at dialogue, and in some way I boiled the play down to its essence, which was eventually published as a twelve-line poem called “Requiem”.

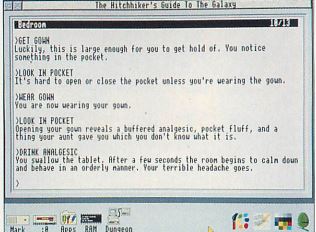

It was during my second year as a DPhil student that The Lost Treasures of Infocom came out. At this time my computer was an Acorn Archimedes with a 20 MB hard drive. I bought the MS-DOS box because I could read the story files from the MS-DOS disks, even if I couldn’t run the MS-DOS interpreter. I had no modem or network access from my house, and could only get files on or off by taking a floppy disk to the computing-service building right across town. I used the InfoTaskforce interpreter to actually play the games on my Archimedes.

So, I would say that the existence of a community-written interpreter was an essential precondition for Inform. In the period from 1990 to 1992, there were two significant Infocom-archaeology projects going on independently, though they were certainly aware of each other: the InfoTaskforce interpreter, and a disassembler called “txd” by Mark Howell. The InfoTaskforce people were based in Australia, and I had no contact with them, but I saw their code. Mark, however, I did exchange emails with. I remember emailing him to ask if anyone had written an assembler to make new games for the Z-Machine, and he replied with some wording close to: “Many people have had many dreams”. I set myself the task of faking a story file just well enough to allow it to execute on the InfoTaskforce interpreter.

I recall that my first self-made story file computed a prime factorisation and then printed the result. Except that it didn’t. I would double-click on the story file, and nothing would happen. I would assume that this was because there was some further table in the story file which I needed to fake: that the interpreter was refusing my file because it lacked this table, let’s say. As a result, I got into a cycle of making more and more elaborate fakes, always with negative results. Eventually I found that these faux story files had been correct all along; it was just that the user interface for the Acorn Archimedes port of the InfoTaskforce interpreter displayed nothing onscreen until the first moment when a game’s output hit the bottom of its virtual display and caused a scroll event. My story files, uniquely in the history of the Z-Machine, simply printed a few lines and then quit. They didn’t produce enough output to scroll, so nothing ever showed up onscreen. (This is why, for several years, the first thing that an Inform-written game did was to print a run of newlines.) So, when I finally managed to make a story file which factorised the numbers 2 to 100, and found that it worked correctly, I had a fairly elaborate assembler. This was called “zass”, and eventually became Inform 1.

The project might have gone no further except for the arrival of Usenet and the rec.arts.int-fiction newsgroup. Suddenly my email address was one which people could contact, and my posts were replied to. I was no longer on GROGGS, talking to a handful of people I knew in real life; I was on Usenet, talking to those I would likely never meet. People didn’t really use Inform much until around Inform 3, but still, there was feedback. An appetite seemed to exist.

A curious echo of the fascination the Z-machine held is that a couple of tiny story files produced by me in the course of these experiments — I remember one with two rooms in it and a few sample objects, one of them a football — themselves started to be collected by people. Of course there were soon to be lots of story files, an unending supply of them. But for just a brief period, even the output of Inform had a sort of second-hand glory reflected onto it.

Inform 1 was the result of my experiments to synthesise a story file, so it preceded Curses; it’s not that I set out to create both. Still, I did once write that Inform and Curses were Siamese twins, though the expression makes me flinch now. It’s not a comedic thing to be born conjoined. That aside, was it true, or did it simply sound clever? It’s true in part. I steadily improved Inform as I was building up Curses in size, and Curses undeniably played a role as a proof of concept. Numerous half-finished interactive-fiction systems had been abandoned with no notable games to their credit, but TADS, especially, shone by having been used for full-scale works. Yet this linkage is only part of the story.

In retrospect, the decision to write Curses fits with the pattern of imitation which you tend to find in the juvenilia of writers. I had read some novels, I wrote a novel; I had read some plays, I wrote a play; and so on. Lost Treasures may have played the same role for me, in computer-game terms, that those 1980s Faber & Faber paperbacks played in literary terms. But I also wrote Curses as an entertainment for my friends back in Cambridge, who attacked it without mercy. A very early version caused hilarity not so much for its intrinsic qualities as because the command “unlock fish” crashed it right out.

The title alludes to the recurring ancestral curses of the Meldrew family, each generation doomed never quite to achieve anything. (Read into that what you will, but it caused my father to raise an amused eyebrow.) The name was actually a hindrance for a while. In the days of Archie and Veronica and other pre-Web systems for searching FTP sites, “curses” was a name already taken by the software library for text windows on Unix.

What is Curses about? A few years ago Emily Short and I were interviewed, one after another, at the Seattle Museum of Pop Culture. Emily described Curses as being about the richness of culture and the excitement of discovering it. This may be an overly generous verdict, but I see what she means. Curses has a kind of exuberance to it. The ferment of what I was reading infuses the game, and although most people saw it as a faithful homage to Infocom, it was also a work of Modernism, assembled from the juxtaposed fragments of other texts. At Meldrew Hall, I could connect everything with everything.

There were four main strands here. Most apparent is the many-volume Oxford History of England, an old-school reference work, which lined up on my shelf in pale blue dust jackets. I had collected them by scouring second-hand book shops with the same assiduity as a kid completing an album of football stickers. Something of each went into Curses, from Roman England (Vol. I) through to society paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and so on. The second strand was Eliot and The Waste Land, not solely for its content but also for its permissive style, as if it had authorised me to throw everything together. The third strand was classics: I was reading a lot of those “Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Philosophy” type of books, and I liked to grab the picturesque parts. Lastly, of course, the fourth strand is Infocom. Some of the puzzle design is lovingly imitative of Lebling, especially. The hieroglyphics from Infidel make a direct appearance. I also took affectionate swipes at the conventions, as with the infamous “You have missed the point entirely” death incurred simply by going down from the opening room, or the part where the narrator awards some points and then, a few turns later, takes them back again. Or the devil, who gives hints, all of which are lies. People actually filed bug reports over that. But really, I don’t think I did anything so transgressive that Infocom might not have done the same itself.

Those four strands are the main ingredients, but I should also acknowledge the indirect influence of the 1980s turn towards magical realism in fantasy novels, where it became possible to marry the fantastical with the merely historical. I had certainly read John Crowley’s Little, Big, for example. You could, at a stretch, say that Curses lies in the same genre.

The art of the Modernist collage is to somehow provide some cement which will hold the whole thing together. In the case of Curses, that cement is provided by the continuity of the Meldrew family and of the house – to which, and this is crucial, the player is always returning, and which ramifies with endless secret rooms. Moreover, you always experience the house through its behind-the-scenes places, joined in a skeletal way around the public areas which you never get to visit. The game is at its best when this cement is strongest, with the puzzles directly related to family members or to the house’s nooks and crannies. It loses coherence when it goes further afield, and this is why a final proposed addition, to do with the subway systems of various world cities all being joined up, was dropped. It didn’t feel like Curses any more. The weakest parts of Curses are the last parts added, and I suspect that the penultimate release is probably a better experience than the final one.

I am sometimes asked if Curses was autobiographical. As the above makes clear, in one sense yes, in that it’s a logbook of my reading. And in another obvious sense, no: I never actually teleported to ancient Alexandria. Nor have I ever lived in a grand house. My family home was built around 1960. It had seven rooms, none of them secret, and its map was an acyclic graph. There were early players who imagined that I might really be from some cadet branch of the landed gentry, with spacious grounds out of my window. This was not the case. Our estate consisted of one apple tree and two gooseberry bushes. All the same, England is not like America in this respect. Because of the Second World War, and because of inheritance tax, the great stately homes of England had essentially all become public places by the time I was a child. A routine way to entertain visiting grandparents was to take them around, say, the Jacobean manor house at Hatfield, where the Cecils had lived since the reign of James I. You didn’t have to be at all rich to do this.

The Attic area of Curses, where the game begins, does also contain just a little of my real family. The most intriguing place in my childhood home was, for sure, the attic, because it was so seldom accessible to me: a windowless but large space, properly floored, but never converted into a living area. My father would develop photographs up there, pouring chemicals into a tray, under a red lamp with a pull-cord switch. He would allow me to pull this cord. The house also had an airing cupboard — that is, a space around the hot-water boiler where towels could be dried. In this cupboard, my mother at one time made home-brew wine, in a sort of slow chemistry experiment with evil-looking demijohns. My brother doesn’t really make an appearance in Curses, which I’m sad about now, but it’s essential that the protagonist has ancestors rather than contemporaries. Though the protagonist has a spouse and children, mentioned right up front, they never appear, which I think is worth noting in a game where almost everything else that is foreshadowed eventually comes to pass.

Curses is by any reasonable standard too hard. In its first releases, I would update it with new material each time I made bug fixes, so that the game evolved and grew. Some players would play each version as it came out, and this enabled them to get further in, because they had prior experience from earlier builds. A dedicated fan base sent in bug reports, my favourite being that the brass key could not be picked up by the robot mouse, because brass is non-magnetic. The reward for any bug reported was that the reporter could nominate a new song to be added to the radio’s playlist, provided that it was both catchy and objectively dreadful. It would be interesting to extract that playlist now and put it on Spotify.

Feedback from players gave Curses a certain polish, but it wasn’t the only thing. I think it’s noteworthy that, just as Infocom had an editor as well as play-testers, so too I had an editor for at least part of the process: Gareth Rees, a Cambridge friend, author of the very wonderful Christminster. Richard Tucker also weighed in. I have the impression that before 1992 works of interactive fiction didn’t have much quality control, not so much because people didn’t want it, but because networking conditions didn’t allow for it.

To my great regret, the source code for Curses is now lost. It was for a while on a disk promisingly labelled “Curses source code”, but that disk is unreadable, and not for want of trying. Somewhere in my many changes of address and computer, I lost the necessary tech, or damaged it. (And Jigsaw too, alas.) It wouldn’t be hard to resurrect something, by working from a disassembly of the story file: there’s actually a tool to turn story files into Inform 6 out there somewhere. I occasionally think of asking if anyone would like to do that, and perhaps produce a faithful Inform 7 implementation.

Today, people play Curses with a walkthrough by their sides. But the game never quite goes away. Mike Spivey told me recently that he introduced himself to modern interactive fiction – “modern” interactive fiction – by playing Curses in 2017. A few people, at least, still tread Meldrew Hall. I remain fond of the place, as you can probably gather from the length of this reminiscence. Once in a blue moon I am tempted to write a sequel, Curses Foiled. But no. Sometimes you really can’t go back.