We humans always seek to understand the new in terms of the old. This applies as much to new forms of media as it does to anything else.

Thus at the dawn of the 1980s, when the extant world of media began to cotton onto the existence of computer software that was more than strictly utilitarian but not action-oriented videogames like the ones being played in coin-op arcades and on home consoles such as the Atari VCS, it looked for a familiar taxonomic framework by which to understand it. One of the most popular of the early metaphors was that of the electronic book. For the graphics of the first personal computers were extremely crude, little more than thick lines and blotches of primary colors. Text, on the other hand, was text, whether it appeared on a monitor screen or on a page. Some of the most successful computer games of the first half of the 1980s were those of Infocom, who drove home the literary associations by building their products out of nothing but text, for which they were lauded in glowing features in respected mainstream magazines and newspapers. In the context of the times, it seemed perfectly natural to sell Infocom’s games and others like them in bookstores. (I first discovered these games that would become such an influence on my future on the shelves of my local shopping mall’s B. Dalton bookstore…)

Small wonder, then, that several of the major New York print-publishing houses decided to move into software. As is usually the case in such situations, they were driven by a mixture of hope and fear: hope that they could expand the parameters of what a book could do and be in exciting ways, and fear that, if they failed to do it, someone else would. The result was the brief-lived era of bookware.

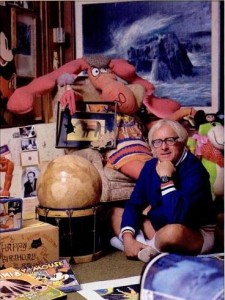

Byron Preiss was perhaps the most important of all the individual book people who now displayed an interest in software. Although still very young by the standards of his tweedy industry — he turned 30 in 1983 — he was already a hugely influential figure in genre publishing, with a rare knack for mobilizing others to get lots and lots of truly innovative things done. In fact, long before he did anything with computers, he was already all about “interactivity,” the defining attribute of electronic books during the mid-1980s, as well as “multimedia,” the other buzzword that would be joined to the first in the early 1990s.

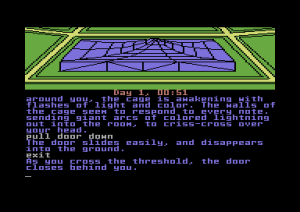

Preiss’s Fiction Illustrated line produced some of the world’s first identifiable graphic novels. These were comics that didn’t involve superheroes or cartoon characters, that were bound and sold as first-run paperbacks rather than flimsy periodicals. Preiss would remain a loyal supporter of comic-book storytelling in all its forms throughout his life.

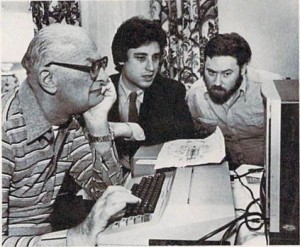

Preiss rarely published a book that didn’t have pictures; in fact, he deserves a share of the credit for inventing what we’ve come to call the graphic novel, through a series known as Fiction Illustrated which he began all the way back in 1975 as a bright-eyed 22-year-old. His entire career was predicated on the belief that books should be beautiful aesthetic objects in their own right, works of visual as well as literary art that could and should take the reader’s breath away, that reading books should be an intensely immersive experience. He innovated relentlessly in pursuit of that goal. In 1981, for example, he published a collection of stories by Samuel R. Delany that featured “the first computer-enhanced illustrations developed for a science-fiction book.” His non-fiction books on astronomy and paleontology remain a feast for the eyes, as does his Science Fiction Masterworks series of illustrated novels and stories from the likes of Arthur C. Clarke, Fritz Leiber, Philip Jose Farmer, Frank Herbert, and Isaac Asimov.

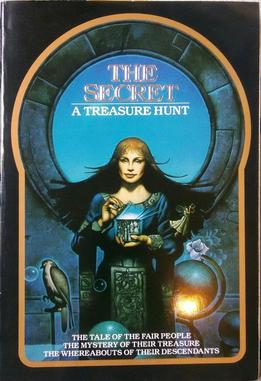

As part and parcel of his dedication to immersive literature, Preiss also looked for ways to make books interactive, even without the benefit of computers. In 1982, he wrote and published The Secret: A Treasure Hunt, a puzzle book and real-world scavenger hunt in the spirit of Kit Williams’s Masquerade. As beautifully illustrated as one would expect any book with which Preiss was involved to be, it told of “The Fair People,” gnomes and fairies who fled from the Old to the New World when Europeans began to cut down their forests and dam the rivers along which they lived: “They came over and they stayed, and they were happy. But then they saw that man was following the same path [in the Americas] and that what had happened in the Old World would probably happen in the New. So the ones who had already come over and the ones who followed them all decided they would have to go into hiding.” They took twelve treasures with them. “I have been entrusted by the Fair People to reveal the whereabouts of the [treasures] through paintings in the book,” Preiss claimed. “There are twelve treasures hidden throughout North America and twelve color paintings that contain clues to the whereabouts of the treasure. Then, there is a poem for each treasure. So, if you can correctly figure out the poem and the painting, you will find one of the treasures.” Each treasure carried a bounty for the discoverer of $1000. Preiss’s self-professed ultimate goal was to use the interactivity of the scavenger hunt as another tool for immersing the reader, “like in the kids’ books where you choose your own ending.”

The Secret failed to become the sales success or the pop-culture craze that Masquerade had become in Britain three years earlier. Only one of the treasures was found in the immediate wake of its publication, in Chicago in 1983. Yet it had a long shelf life: a second treasure was found in Cleveland more than twenty years later. A 2018 documentary film about the book sparked a renewal of interest, and the following year a third treasure was recovered in Boston. A small but devoted cult continues to search for the remaining ones today, sharing information and theories via websites and podcasts.

In a less enduring but more commercially successful vein, Preiss also published three different lines of gamebooks to feed the hunger ignited by the original Choose Your Own Adventure books of Edward Packard and R.A. Montgomery. Unsurprisingly, his books were much more visual than the typical example of the breed, with illustrations that often doubled as puzzles for the reader to solve. A dedicated nurturer of young writing and illustrating talent, he passed the contracts to make books in these lines and others to up-and-comers who badly needed the cash and the measure of industry credibility they brought with them.

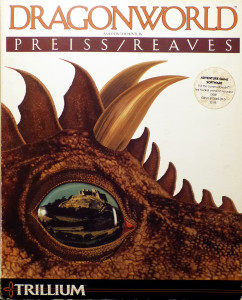

Being a man with a solid claim to the woefully overused title of “visionary,” Preiss was aware of what computers could mean for our relationship with storytelling and information from a very early date. He actually visited Xerox PARC during its 1970s heyday and marveled at the potential he saw there, told all of his friends that this was the real future of information spaces. Later he became the driving force behind the most concentrated and in many ways the most interesting of all the bookware software projects of the 1980s: the Telarium line of literary adaptations, which turned popular science-fiction, fantasy, and mystery novels into illustrated text adventures. I won’t belabor this subject here because I already wrote histories and reviews of all of the Telarium games years ago for this site. I will say, however, that the line as a whole bears all the hallmarks of a Byron Preiss project, from the decision to include colorful pictures in the games — something Infocom most definitely did not provide — to the absolutely gorgeous packaging, which arguably outdid Infocom’s own high standard for same. (The packaging managed to provide a sensory overload which transcended even the visual; one of my most indelible memories of gaming in my childhood is of the rich smell those games exuded, thanks to some irreplicable combination of cardboard, paper, ink, and paste. Call it my version of Proust’s madeleine.) The games found on the actual disks were a bit hit-or-miss, but nobody could say that Telarium didn’t put its best foot forward.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough; the Telarium games weren’t big sellers, and the line lasted only from 1984 to 1986. Afterward, Preiss went back to his many and varied endeavors in book publishing, while computer games switched their metaphor of choice from interactive novels to interactive movies in response to the arrival of new, more audiovisually capable gaming computers like the Commodore Amiga. Even now, though, Preiss continued to keep one eye on what was going on with computers. For example, he published novelizations of some of Infocom’s games, thus showing that he bore no ill will toward the company that had both inspired his own Telarium line and outlived it. More importantly in the long run, he saw Apple’s HyperCard, with its new way of navigating texts non-linearly through association — multimedia texts which could include pictures, sound, music, and even movie clips alongside their words. By the turn of the 1990s, Bob Stein’s Voyager Software was starting to make waves with “electronic books” on CD-ROM that took full advantage of all of these affordances. The nature of electronic books had changed since the heyday of the text adventure, but the idea lived on in the abstract.

In fact, the advances in computer technology as the 1990s wore on were so transformative as to give everyone a bad case of mixed metaphors. The traditional computer-games industry, entranced by the new ability to embed video clips of real actors in their creations, was more fixated on interactive movies than ever. At the same time, though, the combination of hypertext with multimedia continued to give life to the notion of electronic books. Huge print publishers like Simon & Schuster and Random House, who had jumped onto the last bookware bandwagon only to bail out when the sales didn’t come, now made new investments in CD-ROM-based software that were an order of magnitude bigger than their last ones, even as huge names in moving pictures, from Disney to The Discovery Channel, were doing the same. The poster child for all of the taxonomical confusion was undoubtedly the pioneering Voyager, a spinoff from the Criterion Collection of classic movies on laserdisc and VHS whose many and varied releases all seemed to live on a liminal continuum between book and movie.

One has to assume that Byron Preiss felt at least a pang of jealousy when he saw the innovative work Voyager was doing. Exactly one decade after launching Telarium, he took a second stab at bookware, with the same high hopes as last time but on a much, much more lavish scale, one that was in keeping with the burgeoning 1990s tech boom. In the spring of 1994, Electronic Entertainment magazine brought the news that the freshly incorporated Byron Preiss Multimedia Company “is planning to flood the CD-ROM market with interactive titles this year.”

They weren’t kidding. Over the course of the next couple of years, Preiss published a torrent of CD-ROMs, enough to make Voyager’s prolific release schedule look downright conservative. There was stuff for the ages in high culture, such as volumes dedicated to Frank Lloyd Wright and Albert Einstein. There was stuff for the moment in pop culture, such as discs about Seinfeld, Beverly Hills 90210, and Melrose Place, not to forget The Sci-Fi Channel Trivia Game. There was stuff reflecting Preiss’s enduring love for comics (discs dedicated to R. Crumb and Jean Giraud) and animation (The Multimedia Cartoon Studio). There were electronic editions of classic novels, from John Steinbeck to Raymond Chandler to Kurt Vonnegut. There was educational software suitable for older children (The Planets, The Universe, The History of the United States), and interactive storybooks suitable for younger ones. There were even discs for toddlers, which line Preiss dubbed “BABY-ROMS.” A lot of these weren’t bad at all; Preiss’s CD-ROM library is almost as impressive as that of Voyager, another testament to the potential of a short-lived form of media that arguably deserved a longer day in the sun before it was undone by the maturation of networked hypertexts on the World Wide Web.

But then there are the games, a field Bob Stein was wise enough to recognize as outside of Voyager’s core competency and largely stay away from. Alas, Preiss was not, and did not.

The first full-fledged game from Byron Preiss Multimedia was an outgrowth of some of Preiss’s recent print endeavors. In the late 1980s, he had the idea of enlisting some of his stable of young writers to author new novels in the universes of aging icons of science fiction whose latest output had become a case of diminishing returns — names like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke. Among other things, this broad concept led to a series of six books by five different authors that was called Robot City, playing with the tropes, characters, and settings of Asimov’s “Robot” stories and novels. In 1994, two years after Asimov’s death, Preiss also published a Robot City computer game. Allow me to quote the opening paragraph of Martin E. Cirulis’s review of same for Computer Gaming World magazine, since it does such a fine job of pinpointing the reasons that so many games of this sort tended to be so underwhelming.

With all the new interest in computer entertainment, it seems that a day doesn’t go by without another company throwing their hat, as well as wads of startup money, into the ring. More often than not, the first thing offered by these companies is an adventure-game title, because of the handy way the genre brings out all the bells and whistles of multimedia. I’m always a big fan of new blood, but a lot of the first offerings get points for enthusiasm, then lose ground and reinvent the wheel. Design and management teams new to the field seem so eager to show us how dumb our old games are that they fail to learn any lessons from the fifteen-odd years of successful and failed games that have gone before. Unfortunately, Robot City, Byron Preiss Multimedia’s initial game release, while impressive in some aspects, suffers from just these kinds of birthing pains.

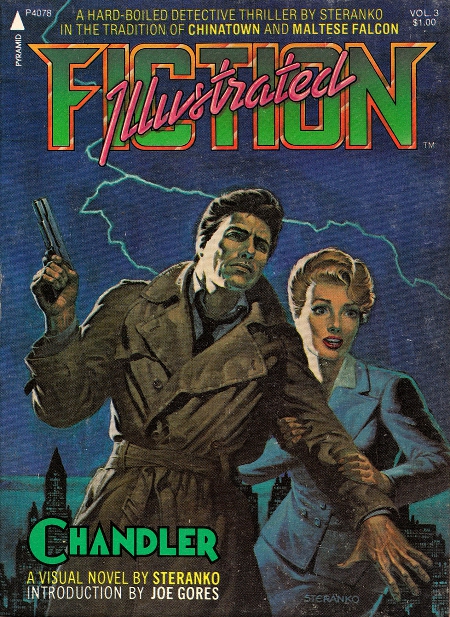

If anything, Cirulis is being far too kind here. Robot City is a game where simply moving from place to place is infuriating, thanks to a staggeringly awful interface, city streets that are constantly changing into random new configurations, and the developers’ decision to put exterior scenes on one of its two CDs and interior scenes on the other, meaning you can look forward to swapping CDs roughly every five minutes.

Robot City. If you don’t like the look of this city street, rest assured that it will have changed completely next time you walk outside. Why? It’s not really clear… something to do with The Future.

Yet the next game from Byron Preiss Multimedia makes Robot City seem like a classic. I’d like to dwell on The Martian Chronicles just a bit today — not because it’s good, but because it’s so very, very bad, so bad in fact that I find it oddly fascinating.

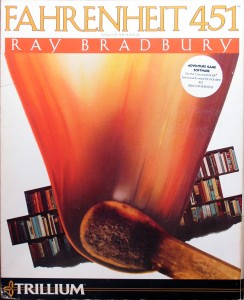

Another reason for it to pique my interest is that it’s such an obvious continuation of what Preiss had begun with Telarium. One of Telarium’s very first games was an adaptation of the 1953 Ray Bradbury novel Fahrenheit 451. This later game, of course, adapts his breakthrough book The Martian Chronicles, a 1950 “fix-up novel” of loosely linked stories about the colonization — or, perhaps better said, invasion — of Mars by humans. And the two games are of a piece in many other ways once we make allowances for the technological changes in computing between 1984 and 1994.

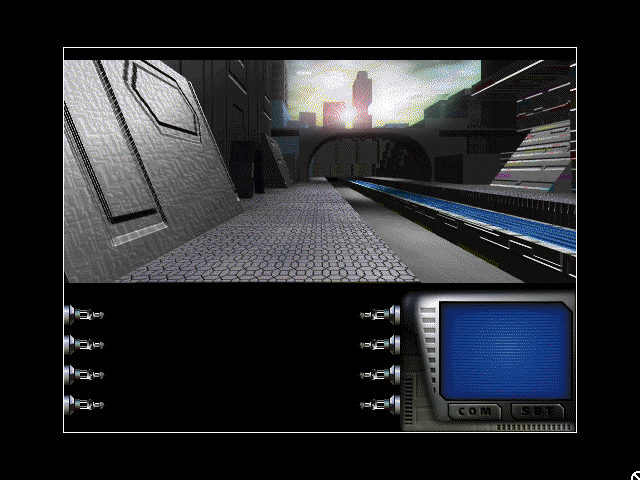

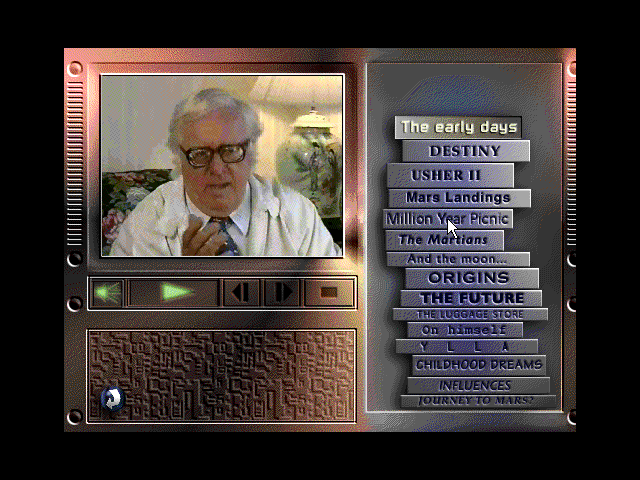

For example, Bradbury himself gave at least a modicum of time and energy to both game projects, which was by no means always true of the authors Preiss chose to honor with an adaptation of some sort. In the Telarium game, you can call Bradbury up on a telephone and shoot the breeze; in the multimedia one, you can view interview clips of him. In the Telarium game, a special “REMEMBER” verb displays snippets of prose from the novel; in the multimedia one, a portentous narrator recites choice extracts from Bradbury’s Mars stories from time to time as you explore the Red Planet. Then, too, neither game is formally innovative in the least: the Telarium one is a parser-driven interactive fiction, the dominant style of adventure game during its time, while the multimedia game takes all of its cues from Myst, the hottest phenomenon in adventures at the time of its release. (The box even sported a hype sticker which named it the answer to the question of “Where do you go after Myst?”) About the only thing missing from The Martian Chronicles that its predecessor can boast about is Fahrenheit 451‘s gorgeous bespoke packaging. (That ship had largely sailed for computer games by 1994; as the scenes actually shown on the monitor got prettier, the packaging got more uniform and unambitious.)

By way of compensation, The Martian Chronicles emphasizes its bookware bona fides by bearing on its box the name of the book publisher Simon & Schuster, back for a second go-round after failing to make a worthwhile income stream out of publishing games in the 1980s. But sadly, once you get past all the meta-textual elements, what you are left with in The Martian Chronicles is a Myst clone notable only for its unusually extreme level of unoriginality and its utter ineptness of execution.

I must confess that I’ve enjoyed very few of the games spawned by Myst during my life, and that’s still the case today, after I’ve made a real effort to give several of them a fair shake for these histories. It strikes me that the sub-genre is, more than just about any other breed of game I know of, defined by its limitations rather than its allowances. The first-person node-based movement, with its plethora of pre-rendered 3D views, was both the defining attribute of the lineage during the 1990s and an unsatisfying compromise in itself: what you really want to be doing is navigating through a seamless 3D space, but technical limitations have made that impossible, so here you are, lurching around, discrete step by discrete step. In many of these games, movement is not just unsatisfying but actively confusing, because clicking the rotation arrows doesn’t always turn you 90 degrees as you expect it to. I often find just getting around a room in a Myst clone to be a challenge, what with the difficulty of constructing a coherent mental map of my surroundings using the inconsistent movement controls. There inevitably seems to be that one view that I miss — the one that contains something I really, really need. This is what people in the game-making trade sometimes call “fake difficulty”: problems the game throws up in front of you where no problem would exist if you were really in this environment. In other schools of software development, it’s known by the alternative name of terrible interface design.

Yet I have to suspect that the challenges of basic navigation are partially intentional, given that there’s so little else the designer can really do with these engines. Most were built in either HyperCard or the multimedia presentation manager Macromedia Director; the latter was the choice for The Martian Chronicles. These “middleware” tools were easy to work with but slow and limiting. Their focus was the media they put on the screen; their scripting languages were never intended to be used for the complex programming that is required to present a simulated world with any dynamism to it. Indeed, Myst clones are the opposite of dynamic, being deserted, static spaces marked only by the buttons, switches, and set-piece spatial puzzles which are the only forms of gameplay that can be practically implemented using their tool chains. While all types of games have constraints, I can’t think of any other strand of them that make their constraints the veritable core of their identity. In addition to the hope of selling millions and millions of copies like Myst did, I can’t help but feel that their prevalence during the mid-1990s was to a large extent a reflection of how easy they were to make in terms of programming. In this sense, they were a natural choice for a company like the one Byron Preiss set up, which was more replete with artists and writers from the book trade than with ace programmers from the software trade.

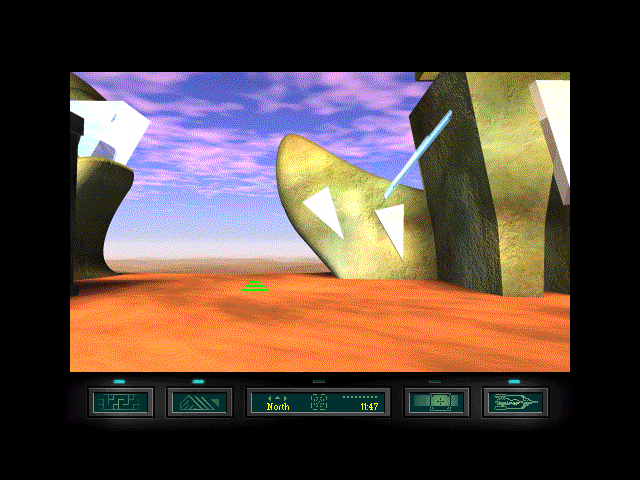

The Martian Chronicles is marked not just by all of the usual Myst constraints but by a shocking degree of laziness that makes it play almost like a parody of the sub-genre. The plot is most kindly described as generic, casting you as the faceless explorer of the ruins of an ancient — and, needless to say, deserted — Martian city, searching for a legendary all-powerful McGuffin. You would never connect this game with Bradbury’s book at all if it weren’t for the readings from it that inexplicably pop up from time to time. What you get instead of the earnest adaptation advertised on the box is the most soul-crushingly dull Myst clone ever: a deserted static environment around which are scattered a dozen or so puzzles which you’ve seen a dozen or more times before. Everything is harder than it ought to be, thanks to a wonky cursor whose hot spot seems to float about its surface randomly, a cursor which disappears entirely whenever an animation loop is playing. This is the sort of game that, when you go to save, requires you to delete the placeholder name of “Save1” character by character before you can enter your own. This game is death by a thousand niggling little aggravations like that one, which taken in the aggregate tell you that no actual human being ever tried to play it before it was shoved into a box and shipped. Even the visuals, the one saving grace of some Myst clones and the defining element of Byron Preiss’s entire career, are weirdly slapdash, making The Martian Chronicles useless even as a tech demo. Telarium’s Fahrenheit 451 had its problems, but it’s Infocom’s Trinity compared to this thing.

It’s telling that many reviewers labelled the fifteen minutes of anodyne interview clips with Ray Bradbury the best part of the game.

Some Myst clones have the virtue of being lovely to look at. Not this one, with views that look like they were vandalized by a two-year-old Salvador Dali wannabee with only two colors of crayon to hand.

Computer Gaming World justifiably savaged The Martian Chronicles. It “is as devoid of affection and skill as any game I have ever seen,” noted Charlies Ardai, by far the magazine’s deftest writer, in his one-star review. Two years after its release, Computer Gaming World named it the sixteenth worst game of all time, outdone only by such higher-profile crimes against their players as Sierra’s half-finished Outpost and Cosmi’s DefCon 5, an “authentic SDI simulation” whose level of accuracy was reflected in its name. (DefCon 5 is the lowest level of nuclear threat, not the highest.) As for The Martian Chronicles, the magazine called it “tired, pointless, and insulting to Bradbury’s poetic genius.” Most of the other magazines had little better to say — those, that is, which didn’t simply ignore it. For it was becoming abundantly clear that games like these really weren’t made for the hardcore set who read the gaming magazines. The problem was, it wasn’t clear who they were made for.

Still, Byron Preiss Multimedia continued to publish games betwixt and between their other CD-ROMs for another couple of years. The best of a pretty sorry bunch was probably the one called Private Eye, which built upon the noir novels of Raymond Chandler, one of Preiss’s favorite touchstones. Tellingly, it succeeded — to whatever extent it did — by mostly eschewing puzzles and other traditional forms of game design, being driven instead by conversations and lengthy non-interactive cartoon cut scenes; a later generation might have labeled it a visual novel. Charlies Ardai rewarded it with a solidly mediocre review, acknowledging that “it don’t stink up da joint.” Faint praise perhaps, but beggars can’t be choosers.

The Spider-Man game, by contrast, attracted more well-earned vitriol from Ardai: “The graphics are jagged, the story weak, the puzzles laughable (cryptograms, anyone?), and the action sequences so dismal, so minor, so clumsy, so basic, so dull, so Atari 2600 as to defy comment.” Tired of what Ardai called Preiss’s “gold-into-straw act,” even Computer Gaming World stopped bothering with his games after this. That’s a pity in a way; I would have loved to see Ardai fillet Forbes Corporate Warrior, a simplistic DOOM clone that replaced monsters with rival corporations, to be defeated with weapons like Price Bombs, Marketing Missiles, Ad Blasters, Takeover Torpedoes, and Alliance Harpoons, with all of it somehow based on “fifteen years of empirical data from an internationally recognized business-simulation firm.” “Business is war, cash is ammo!” we were told. Again, one question springs to mind. Who on earth was this game for?

Corporate Warrior came out in 1997, near the end of the road for Byron Preiss Multimedia, which, like almost all similar multimedia startups, had succeeded only in losing buckets and buckets of money. Preiss finally cut his losses and devoted all of his attention to paper-based publishing again, a realm where his footing was much surer.

I hasten to add that, for all that he proved an abject failure at making games, his legacy in print publishing remains unimpeachable. You don’t have to talk to many who were involved with genre and children’s books in the 1980s and 1990s before you meet someone whose career was touched by him in a positive way. The expressions of grief were painfully genuine after he was killed in a car accident in 2005. He was called a “nice guy and honest person,” “an original,” “a business visionary,” “one of the good guys,” “a positive force in the industry,” “one of the most likable people in publishing,” “an honest, dear, and very smart man,” “warm and personable,” “charming, sophisticated, and the best dresser in the room.” “You knew one of his books would be something you couldn’t get anywhere else, and [that] it would be amazing,” said one of the relatively few readers who bothered to dig deep enough into the small print of the books he bought to recognize Preiss’s name on an inordinate number of them. Most readers, however, “never think about the guy who put it together. He’s invisible, although it wouldn’t happen without him.”

But regrettably, Preiss was a textbook dilettante when it came to digital games, more intrigued by the idea of them than he was prepared to engage with the practical reality of what goes into a playable game. It must be said that he was far from alone in this. As I already noted, many other veterans of other forms of media tried to set up similar multimedia-focused alternatives to conventional gaming, and failed just as abjectly. And yet, dodgy though these games almost invariably were in execution, there was something noble about them in concept: they really were trying to move the proverbial goalposts, trying to appeal to new demographics. What the multimedia mavens behind them failed to understand was that fresh themes and surface aesthetics do not great games make all by themselves; you have to devote attention to design as well. Their failure to do so doomed their games to becoming a footnote in history.

For in the end, games are neither books nor movies; they are their own things, which may occasionally borrow approaches from one or the other but should never delude themselves into believing that they can just stick the adjective “interactive” in front of their preferred inspiration and call it a day. Long before The Martian Chronicles stank up the joint, the very best game designers had come to understand that.

Postscript: On a more positive note…

Because I don’t like to be a complete sourpuss, let me note that the efforts of the multimedia dilettantes of the 1990s weren’t always misbegotten. I know of at least one production in this style that’s well worth your time: The Dark Eye, an exploration of the nightmare consciousness of Edgar Allan Poe that was developed by Inscape and released in 1995. On the surface, it’s alarmingly similar to The Martian Chronicles: a Myst-like presentation created in Macromedia Director, featuring occasional readings from the master’s works. But it hangs together much, much better, thanks to a sharp aesthetic sense and a willingness to eschew conventional puzzles completely in favor of atmosphere — all the atmosphere, I daresay, that you’ll be able to take, given the creepy subject matter. I encourage you to read my earlier review of it and perhaps to check it out for yourself. If nothing else, it can serve as proof that no approach to game-making is entirely irredeemable.

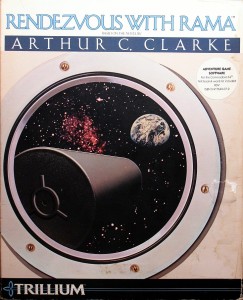

Another game that attempts to do much the same thing as The Martian Chronicles but does it much, much better is Rama, which was developed by Dynamix and released by Sierra in 1996. Here as well, the link to the first bookware era is catnip for your humble author; not only was Arthur C. Clarke adapted by a Telarium game before this one, but the novel chosen for that adaptation was Rendezvous with Rama, the same one that is being celebrated here. As in The Martian Chronicles, the lines between game and homage are blurred in Rama, what with the selection of interview clips in which Clarke himself talks about his storied career and one of the most lauded books it produced. And once again the actual game, when you get around to playing it, is very much in the spirit of Myst.

But Dynamix came from the old school of game development, and were in fact hugely respected in the industry for their programming chops; they wouldn’t have been caught dead using lazy middleware like Macromedia Director. Rama rather runs in a much more sophisticated engine, and was designed by people who had made games before and knew what led to playable ones. It’s built around bone-hard puzzles that often require a mathematical mind comfortable with solving complex equations and translating between different base systems. I must admit that I find it all a bit dry — but then, as I’ve said, games in this style are not usually to my taste; I’ve just about decided that the games in the “real” Myst series are all the Myst I need. Nevertheless, Rama is a vastly better answer to the question of “Where do you go after Myst?” than most of the alternatives. If you like its sort of thing, by all means, check it out. Call it another incarnation of Telarium 2.0, done right this time.

(Sources: Starlog of November 1981, December 1981, November 1982, January 1984, June 1984, April 1986, March 1987, November 1992, December 1992, January 1997, April 1997, February 1999, June 2003, May 2005, and October 2005; Compute!’s Gazette of December 1984; STart of November 1990; InCider of May 1993; Electronic Entertainment of June 1994, December 1994, January 1995, May 1995, and December 1995; MacUser of October 1995; Computer Games Strategy Plus of November 1995; Computer Gaming World of December 1995, January 1996, October 1996, November 1996, and February 1997; Next Generation of October 1996; Chicago Tribune of November 16 1982. Online sources include the announcement of Byron Preiss’s death and the outpouring of memories and sentiment that followed on COMICON.com.

A search on archive.org will reveal a version of The Martian Chronicles that has been modified to run on Windows 10. The Collection Chamber has a version of Rama that’s ready to install and run on Windows 10. Mac and Linux users can import the data files there into their computer’s version of ScummVM.)