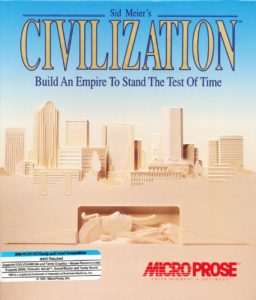

If my gravestone says, “Sid Meier, developed Civilization,” I’m happy with that. It’s a game I’m happy to be known for.

— Sid Meier

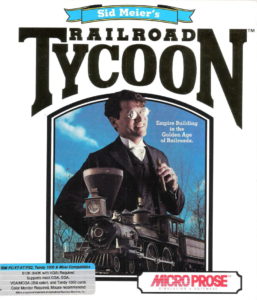

During Sid Meier’s astonishingly productive first ten years as a designer and programmer, games poured out of him in such a jumble that even his colleagues at MicroProse Software could have trouble keeping straight what all he was working on at any given time. At the beginning of 1990, for instance, he had no fewer than three ambitious projects on the boil. He and his protege Bruce Shelley were finishing up Railroad Tycoon with justifiable enthusiasm. The same pair was, with considerably less enthusiasm, returning to Covert Action, one of the rare Meier designs that he could just never quite get to work to his satisfaction. And then — because what else should a recently married game designer spend his evenings doing? — Meier had embarked on a third project on his own time, a game he was already calling Civilization.

Like Railroad Tycoon before it, Civilization was born out of Meier’s abiding fascination with SimCity. The programmer and simulation designer inside him recognized Will Wright’s so-called “software toy” to be a stunning achievement, yet the purer game designer within him was always a bit frustrated by the aimlessness of the experience. Thus Railroad Tycoon had attempted to take some of the appeal of SimCity and “gamify” it by adding computerized opponents and a concrete ending date. It had succeeded magnificently on those terms, but Meier wasn’t done building on what Wright had wrought. In fact, his first conception of Civilization cast it as a much more obvious heir to SimCity than even Railroad Tycoon had been. Whereas SimCity had let the player build her own functioning city, Civilization would let her build a whole network of them, forming a country — or, as the game’s name would imply, a civilization.

This, then, was the first of three conceptual layers which would eventually make up the game of Civilization that the world would come to know. Meier abstracted away most of the details of the individual cities, letting the player decide only on which key buildings were built, whilst boiling each city down to a handful of numbers detailing its population, its economy, and its quality of life. This being a country rather than a city simulator, the spaces between the cities were just as important as the urban centers themselves. Meier thus made it possible to irrigate the countryside, to build roads to facilitate commerce, to build mines for digging up the raw materials needed by the centers of industry. At this early stage, Civilization, later to be hailed as the most iconic exemplar of turn-based grand-strategy games, ran in real time, like SimCity and Railroad Tycoon before it.

Around March of 1990, after working on Civilization for some months completely alone, Meier began to include Bruce Shelley in the role of sounding board. Shelley worked a standard eight-to-five day at MicroProse most of the time, while Meier hewed to a typical hacker’s schedule, showing up at noon or shortly before and working late into the evening. Each night, before he went home, he’d leave a disk on Shelley’s chair with the latest version of Civilization. The next morning, when Shelley arrived at work, he’d play it for an hour or so in order to give Meier his feedback. For perhaps as long as a year, Shelley was literally the only person allowed to play the nascent Civilization, under strict instructions to ignore the pleas of his colleagues peering over his shoulder. It was, to say the least, an unorthodox model of game development, but it somehow worked for these two unique personalities. Far from remaining just a glorified play-tester for very long, Shelley got deeper and deeper into the design. As he did so, Civilization started to become something else entirely.

The switch from a real-time to a turn-based approach was made quite early on, possibly even before those disks started appearing on Bruce Shelley’s chair. It would be wonderful to know the details behind the decision, but neither Meier nor Shelley can recall much of the specifics. It’s likely, however, that the change was made when Meier and Shelley — or Meier alone — started mulling over how to prevent Civilization from falling into the SimCity trap of becoming more of a software toy than a game in the traditional sense. The obvious way to gameify the experience was to include competing civilizations, just as Railroad Tycoon had included competing robber barons. But conflicts between civilizations, unlike conflicts between business interests, always have looming over them the prospect of that ultimate diplomatic arbiter: war. So, including competing civilizations seemed to demand that a whole new layer of wargame strategy be mated to the existing game of city and country development.

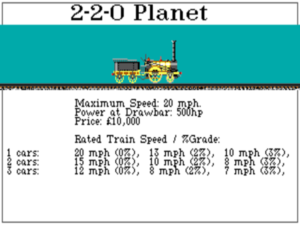

Meier, who somehow found time to remain an avid player of strategy games when he wasn’t developing them, had for years been playing one called Empire, a design so old that it had been born on a big DEC PDP-10 rather than a microcomputer. Empire has a complicated pre-commercial history, which is complicated further by the fact that at least three mostly or entirely separate games were given the name over the course of the 1970s. But the most relevant version for our purposes was created by Walter Bright, a 20-year-old student at the California Institute of Technology, in 1977. Bright himself later ported it to microcomputers, efforts which culminated in him selling the game to a small publisher called Interstel, who made something of a specialty out of pulling hoary old classics out of the dustbin of 1970s institutional computing, giving them a coat of spit and polish, and introducing them to the home-computer-owning public. (Their first game, 1984’s Star Fleet I: The War Begins!, had done the same thing for the old mainframe Star Trek game.) It was Interstel’s version of Empire, published in 1987 with the subtitle Wargame of the Century, that Sid Meier knew best.

At a time when companies like SSI were publishing bafflingly complicated wargames in the name of faithfulness to history, Empire stood out for its elegant simplicity; it was more Risk than Squad Leader. A world on which to play is chosen or, more commonly, generated randomly for each game. You begin in possession of a single city surrounded by just eight visible squares of the 5684 of them that make up the map; the rest of the world remains a mystery. Each city can be assigned to build one of a handful of armies, aircraft, and ships, each of which demands a set number of turns to bring to completion. Your first objective must be to build a unit in your first city and set out to explore the map as quickly as possible, taking possession of any neutral cities you discover. But eventually you run into the units and cities of your competitors, whereupon you all duke it out, leaving the last person left standing as the winner. Simplicity really is the watchword throughout. The military units, for instance, have their capabilities abstracted into just a handful of numbers: a movement speed, an attack rating, a defense rating, a damage rating describing the number of hits required to destroy it. Combat occurs when one player drives a unit into a square occupied by an enemy unit, whereupon the computer throws a virtual die, runs the result through an equation, and announces the outcome of the battle. A certain kind of player lauds Empire as a pure strategy game, a balanced challenge which rewards purely strategic thinking instead of muddying the issue with the superiority of Nazi optics versus the better armor of Allied tanks and all the rest. (Of course, another kind of player, of a more experiential bent, finds it utterly uninteresting for the same reason.)

There’s really no delicate way to put this: confirming the old adage that good artists borrow while great ones steal, Sid Meier pretty much ripped off Empire wholesale and transported it into his burgeoning Civilization. The unknown map just begging to be revealed, the combat system, even many of the specific commands a player could issue to her units… all arrived virtually unchanged in Civilization, to such an extent that anyone who had played Empire — and Bruce Shelley, for one, certainly had — would immediately know what to do. Where Meier did make changes, it was generally to simplify Empire‘s already hugely abstracted approach to wargaming yet further. For example, he removed the damage rating from his units altogether in favor of a one-hit-and-you’re-done model. (This would lead to one of the more indelible images of Civilization in the cultural memory: that of a Greek phalanx destroying, thanks to a lucky roll of the virtual die, a platoon of modern tanks.)

By this point, Meier and Shelley had a fairly credible game already, a version of Empire grafted to a city-building game of economic development which determined how many and what sorts of military units the player could produce and support. Said units were confined to the ancient era: legions, phalanxes, chariots, cavalry. Shelley remembers the two of them discussing the fact that, should worse come to worst, they could probably just polish up what they had and release it as a beer-and-pretzels strategy game of the Punic Wars or something. Yet neither one was at all inclined to do so; to turn Civilization into a just another conquer-the-world game would be to lose some palpable if unarticulated sense of otherness that had been lurking within the project from the very beginning.

Civilization‘s Advances Chart is one of the most awe-inspiring documents I’ve ever encountered in my life. Colloquially referred to as the “tech tree,” it actually encompasses much more than that name would imply. It’s rather an endlessly fascinating chronicle of human progress, of what begot what, not just in the realm of technology but in those of art, culture, thought… in everything. I love it so much that I very nearly started another blog just to explore its interconnections. Yes, really.

The moment when they discovered their game’s true reason for existing came when they conjured up the “Advances Chart,” a timeline of scientific, technological, and cultural advancements up which the player could guide her civilization. With this idea, the third and most defining layer of the game fell into place. Not only did it change the game, it also changed the nature of the design process. The pair’s afternoons were soon filled by discussions — and occasional arguments — ranging back and forth across the timeline of progress. Others inside MicroProse’s cramped offices found these discussions so fascinating that they couldn’t help listening in, to the detriment of their own productivity. Shelley remembers making one proposal that wouldn’t ultimately make it into the game, for introducing a technology no less plebeian than the stirrup to the Advances Chart. “Why the stirrup?” asked a baffled Meier. Well, explained Shelley, horse-borne warfare didn’t instantly begin when people began riding horses; if you hit someone with a lance while riding without stirrups you’d wind up pushing yourself right off the horse. Knights in shining armor, massed cavalry charges, cowboys and Indians… the humble stirrup, just as much as the domestication of horses, had been the key to all of it. These were the sorts of insights Civilization was now giving its designers, as it soon would its players as well.

Beyond the starting slate of seven possibilities for research, the Advances Chart was based on prerequisites: to research Mysticism required one to already have discovered Ceremonial Burial, to research Chivalry required one to have Horseback Riding and Feudalism. The prerequisites were partially based on gameplay considerations, but at least as often teased out real, sometimes subtle linkages between the great achievements of humanity. Why, for instance, should Democracy require Literacy? Because a functioning democracy requires a literate population able to read for themselves and make responsible decisions from a position of knowledge, that’s why. Why should Labor Unions require Mass Production? Because the awful working conditions in factories provided the impetus for organizing and collectively demanding better conditions from the moneyed interests who owned the factories, that’s why.

In order to form such connections, Meier and Shelley spent hours poring over history books, trying to understand what begot what and why. They were undoubtedly punching above their weight in trying to wrestle into place so all-encompassing a document as the Civilization Advances Chart — who wouldn’t be? — but they were helped by the fact that both had been dedicated readers of history for years, amassing substantial personal libraries. [1]Soren Johnson, who many years later worked as co-designer of Civilization III and lead designer of Civilization IV, remembers Meier loaning him some reference books near the beginning of his involvement with the franchise, telling him that they might be good resources to use in refining or expanding the Advances Charts of the earlier games. Flipping through the books, he noticed underlined phrases like “ceremonial burial.” With a start, he realized that he had in his hands a history book that had itself become a piece of history: one of Sid Meier’s original sources for the original Civilization. And when said personal libraries failed them, they could take advantage of the location of MicroProse’s offices in suburban Baltimore by making the short drive to one of the Smithsonian museums or the Library of Congress.

Meier and Shelley didn’t, as would have been all too easy for two old grognards like them, limit their research to the realm of the military, nor for that matter to the military-industrial complex. As some of the examples I’ve already named illustrate, they really did try to encompass everything on their Advances Chart, including philosophy, the arts, even the slow march of human rights toward true equality. They resisted the natural urge to dismiss or belittle those things which fell outside the compass of their usual interests. Here, another Shelley anecdote is telling. Very late in the game’s development, he asked one of MicroProse’s artists, who given the company’s usual product portfolio was accustomed to drawing pictures of soldiers, tanks and airplanes, to draw a picture of Michelangelo’s David statue for the Civilization manual. Why on earth do you want a picture of that, asked the artist. Shelley admitted that he was no great art historian or even art enthusiast. But, he said, people who are those things have told me via their books that this statue is very, very important — even, some of them might say, one of the great achievements of human civilization — and I respect their point of view. That noble broad-mindedness became an essential part of Civilization‘s personality, keeping it from becoming just another min-max-ing exercise in conflict management. I recently praised the Dr. Brain series of educational games from Sierra for their unwillingness to be confined to a single topic, for the implicit argument they make that all fields of human endeavor are equally worthy. Vastly different though it is as a game, Civilization manifests the same spirit.

By the time the Advances Chart extended to roughly the present day, the simple mechanisms Meier and Shelley had built the game around were finally beginning to break down. Meier remembers the introduction of aircraft units, which demanded that some ugly special rules be grafted onto the heretofore beautifully simple Empire-derived military layer, as a particular inflection point, a sign to the two designers that it was about time to wrap things up. He recalls introducing pollution to the game at least partly as a way of sending the same signal to the player.

Still, the spirit of the Advances Chart would clash horribly with a game which could be won only by conquering the world. What could become an alternative endgame for the player who preferred building to conquering? It was Shelley who suggested the perfect builder’s path to victory: advancing all the way to the end of the Advances Chart would allow you to build and launch a spaceship for Alpha Centauri, thus inaugurating the next great phase of humanity’s existence. Granted, it didn’t quite make sense in the context of the rest of the advances chart, which otherwise confined itself to things that had already been discovered or that hopefully would be in the fairly near future. Civilization would offer no explanation of how humanity would go from Robotics, (Apollo-style) Space Flight, and Plastics to bridging the 4.37 light years that separate our solar system from its closest neighbor — a leap that could require a whole other Advances Chart at least as big as the one Meier and Shelley already had to actually bring to fruition in any sort of grounded way. One could argue that a voyage to Mars might have made a better final goal, but Meier and Shelley clearly wanted something audacious, and audacious a trip to Alpha Centauri certainly is.

Now it only remained for the two designers to glue their three layers of gameplay into a coherent whole. On the surface, this seemed far from a simple task. The issues of scaling they faced would have defeated many a designer: military operations took place on a scale of days and weeks, construction projects played out on a scale of months and years, while cultures moved up the Advances Chart only over a time frame of decades and centuries.

My regular readers may recall that this same pair of designers had faced an only slightly less extreme version of this clash of time and scale with Railroad Tycoon. There the question had been how to integrate the operational aspect of the game — also known as the “model-railroading” aspect — with the business of running a real railroad over a period of years and decades. They solved the problem, you may recall, by effectively ignoring it, by running the entire game on the macro time scale of the business layer and just letting the operational layer deal with it. This meant that individual trains could take months between leaving one station and arriving at another, and that major transportation corridors like Boston to New York might be served by just two or three train departures per year. You could rationalize all of this as an abstraction of the hundreds of trains that were really running over these tracks, or you could just not think about it at all. The point was that it led to a fun game that captured the spirit of its subject matter.

Faced with the same problem in Civilization, Meier and Shelley took the exact same approach. The game would run on a time frame appropriate to the theme of human progress on the grand scale. Each turn would represent fully twenty years from 4000 BC to AD 1000, followed by ten years until 1500, five years until 1750, two years until 1850, and one year thereafter; the shortening spans of time would depict the steadily accelerating pace of progress as the world lurched toward modernity. This had some extremely weird implications for the Empire-derived military game in particular: it meant that battles could conceivably span centuries — the Trojans and the Greeks had nothing on this lot! — and wars could potentially span millennia. For that matter, it meant that just marching a phalanx from one side of one’s country to the other could require a couple of centuries in itself. You can, once again, choose to rationalize this as an abstraction of reality, or you can just not think about it. Yet again, the point is that it’s fun and that it works for the game.

With the three layers of the design thus welded together, the rest of the game we’ve come to know as Civilization fell into place. Meier and Shelley turned to the history books again to select fifteen current or historical cultures for inclusion, from the Americans to the Zulus, one of which the player could choose to play, the others of which would serve as potential rival civilizations. Fairly rudimentary artificial intelligence came in for this last group, with the behavior of each rival civilization’s leader defined on an axis of three values, from “militaristic” to “civilized,” from “aggressive” to “friendly,” from “expansionist” to “perfectionist.” An extremely rudimentary diplomatic model came in, with geopolitical relations boiled down to make war or make peace, demand tribute or pay tribute.

The final indelible piece of the Civilization experience arrived in the form of “Wonders of the World,” special structures which only one civilization would be allowed to build in one city in the course of an entire game. Each would confer some tangible benefit, but just as important would be the bragging rights of having constructed the Pyramids of Giza or the Great Wall of China. While the idea and the name were obviously inspired by the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, Meier and Shelley wound up using only four of the Seven. The balance of the list was filled out with seventeen other landmark achievements, many of them not actually physical structures at all: Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world, Darwin’s theory of evolution, the United Nations, the Apollo moon landings, even — reaching now into the realm of wishful thinking — a cure for cancer. Just as had happened with the Advances Chart, the list of Wonders became far more wide-ranging than one would have any right to expect. How many other grognards would have taken the time to single out women’s suffrage as one of the Wonders of the World?

Other designers — some of them great ones — had occasionally dreamed about a game of this scale and scope, but none had ever come close to bringing the dream to fruition. At the very same time that Meier and Shelley were working on Civilization, two other hugely admired designers were coincidentally each working on a similarly themed project of their own, only to be forced to scale it back dramatically. Dan Bunten [2]Dan Bunten began living as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry shortly after the publication of Global Conquest. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. wound up with Global Conquest, a competent but less than earth-shaking conquer-the-world strategy game, while Chris Crawford wound up with a game every bit as unfun as its title would imply: The Global Dilemma: Guns or Butter.

Why, we might ask, did Civilization turn out differently? A big piece of the reason must be Sid Meier’s unwavering commitment to fun as the final arbiter in game design, as summed up in his longstanding maxim of “Fun trumps history.” Meier, Bunten, and Crawford actually met on at least one occasion to discuss the games of everything they each had in progress. Crawford’s recollections of that meeting are telling, even if they’re uttered more in a tone of condemnation than approbation: “Sid had a very clear notion: he was going to make it fun. He didn’t give a damn about anything else; it was going to be fun. He said, ‘I have absolutely no reservation about fiddling with realism or anything, so long as I can make it more fun.'”

But another, less obvious piece of the puzzle is inherent to the way that Civilization was developed. Imagine yourself in the shoes of a designer who’s just decided to make a game about everything. How do you even begin? What rules, what mechanics, what interface can you possibly employ? It is, needless to say, a daunting prospect. Game design being an art of the possible, you inevitably begin to pare away at your grand vision, trying to arrive at some core which you can actually hope to implement. In the process, though, you also begin cutting into the soul of the idea, until you arrive at a dispiriting shadow of it like Global Conquest or The Global Dilemma. Sid Meier, by contrast, never really decided to make a game about everything at all; his design just kind of went there on its own. Thus while Bunten and Crawford were cutting back on their ambitions, Meier was expanding on his. Rather than arriving as an immaculate conception, Civilization was allowed to grow into itself, employing rules, mechanics, and interfaces which had already been proven on smaller scales.

A persistent question surrounding Civilization the computer game — and one that has come to have urgent legal relevance — has been the influence of an earlier game with the same name, a board game designed by Francis Tresham and self-published by him in 1980, then re-published under the Avalon Hill imprint the following year. The theme of the board game matches that of the computer game — the advancement of human civilization from its formative stages — and the two share other eyebrow-raising similarities. An Advances Chart not at all far removed from the one in the computer game is implemented in the board game as well via a deck of cards, and even some of the individual advances in the board game lend their names to those in the computer game. On the other hand, the board game ends in approximately 250 BC, while, as already noted, the computer game stretches into the near future.

Seasoned grognards that they were, Meier and Shelley could hardly not have been acquainted with the Avalon Hill game, which enjoyed considerable popularity in its day among the hardcore wargame crowd who were willing to devote the five or six hours that a complete playthrough of it usually required. Yet Meier — who, it should be noted, has always been very transparent about the inspirations for his games — has claimed to have played the board game only once in his life, and not to have had it in mind at all when he started making the computer game. Shelley, who worked at Avalon Hill prior to coming to MicroProse, admits to considerably more familiarity, but likewise dismisses the notion of having borrowed anything more than certain themes and a name, the latter apparently with no regard to what had come before. Sid Meier could be, much to MicroProse head “Wild” Bill Stealey’s chagrin, extremely naive about matters of business and intellectual property, and simply stuck the obvious name on his own game without ever thinking about what conflicts it might create.

Stealey was no grognard, and thus had no idea about the name’s history until MicroProse had already begun advance promotion of their take on Civilization. It was at this point that a very unhappy Eric Dott, the president of Avalon Hill, called him up and said, “Wild Bill, Civilization is my game. You’re stealing it.” Further complicating the situation was the fact that the same two men had had very nearly the same conversation barely a year before, when MicroProse had published Railroad Tycoon. Dott had been convinced then that the game in question bore suspicious similarities to the Avalon Hill board game 1830: Railways & Robber Barons, ironically also a Francis Tresham design, and one on which Bruce Shelley had done some work during his time at the company. Stealey had been able to smooth things over then, but now here they were again, and with what seemed a much more clear-cut case of trademark infringement at that. To make matters that much worse, Avalon Hill was about to unveil a set of expanded rules for the original Civilization board game under the name of Advanced Civilization, and was thus particularly unenthused about having a computer game with the same name confusing the issue at this of all junctures.

Wild Bill can best explain what happened next in his own inimitable style:

So, I had lunch with Eric. I bought him lunch because I was buttering him up. I said, “Eric, I apologize. I didn’t know Sid was doing this, but I think it’s going to be a good game. I think we won’t sell near as many as you sell as boxed games.” You know, one of those games you buy in a box and play on a table — tabletop games. “What if I put a card in every one of the games that says, ‘Get $5 off Civilization from Avalon Hill,’ and you do the same for me?'” After two or three glasses of wine, he agreed — one of his bigger mistakes. He would have made a lot more money if he had said, “Okay, give me 10 percent of it.” All he got was a card in the game box. If he had 10 percent of Civilization, Avalon Hill would still be around today, right?

Of course, the presence of those cards in the boxes did nothing to ease the confusion surrounding these two very different games with the same name. To this day, there are many who believe Sid Meier’s Civilization to be merely a computerized version of the board game.

Stealey and Dott’s gentleman’s agreement wouldn’t keep the lawyers at bay forever; the issue would be revisited again, with major consequences for all involved. But that would be only years in the future, and thus must be fodder for a much later article of mine.

By the time Stealey and Dott had their tête-à-tête, the duo of Meier and Shelley had long since begun including their colleagues in the Civilization development and play-testing process. The game had a split reputation inside MicroProse. The technical and creative staff, almost to a person, loved it, was convinced that this was not just another game, not even just another very good Sid Meier game, but a true landmark in the offing for their company and for their industry. And yet the more businesslike side of the company, taking their cue from the man at the top of the food chain, was rather less enthused.

The fact of the matter was that Wild Bill Stealey wasn’t capable of getting truly, personally enthused over any game that wasn’t a military flight simulator. Just as had happened with Pirates! and Railroad Tycoon, Sid Meier’s two earlier masterpieces, he never quite seemed to grasp what his star designer was on about with Civilization, couldn’t seem to understand why he preferred to spend his time on a high-falutin’ project like this one instead of, say, F-15 Strike Eagle III. Yet Meier, whose confidence in himself had grown with every game of his that MicroProse published, was no longer a designer to whom Stealey could dictate directions; the last gasp of that had been his reluctantly finishing up Covert Action at Stealey’s insistence. Faced with that reality, Stealey duly provided Civilization with the artists and other resources Meier and Shelley needed to finish it, announced the game to the press (thus leading to that fateful lunchtime truce with Eric Dott), and even ran some modest pre-release advertisements. But he wasn’t overly generous with the Civilization development team; certainly the finished game is no graphical feast, with a look that verges at times on amateurish. Shelley in particular has described his frustration with feeling perpetually under-appreciated by MicroProse’s management. The final insult came when, after shipping their staggeringly ambitious game in December of 1991, he and Meier saw their bonuses cut because they had done so six weeks late, missing the bulk of the Christmas buying season.

Whatever Stealey personally thought of Civilization, his ambivalence is by no means the only explanation for the relative lack of resources at his star designer’s disposal. Meier, who had co-founded MicroProse with Stealey back in 1982, had seven years later made a conscious decision to step back from the roller-coaster ride that running a company alongside Wild Bill was always doomed to be. In 1989, he had convinced Stealey to buy him out so he could focus strictly on designing games, becoming a “super contractor” for what had once been his own company. Still, nothing could entirely insulate him and Shelley and their latest game from an unstable situation around them. The fact was that MicroProse was in a rather precarious position as Meier and Shelley were finishing their latest masterpiece. The problems reached back to 1988, when Stealey, having seen his company clear $1 million in profit the previous year, embarked on two major new initiatives that pushed them well outside their comfort zone of military simulations for American home computers. Neither of them would have a happy ending.

One of the new initiatives was an aggressive expansion into the European market, including a new branch office in Britain and the purchase of the Firebird and Rainbird labels from British Telecom. In principle, opening a MicroProse subsidiary in Britain was a smart, even visionary move to get in on the second biggest computer-game market in the world, but the move was horribly mismanaged from the start, collapsing into chaos in the summer of 1989, when Stealey flew to Britain to personally accuse a managing director of embezzling £200,000 from the company coffers. The purchase of Firebird and Rainbird, on the other hand, didn’t make much sense even at the time as anything other than expansion for expansion’s sake — their collection of action games and old-school text adventures didn’t sit terribly well beside the MicroProse catalog — and quickly turned out to be a bust, with both labels, which had enjoyed considerable respect at the time of the purchase, disappearing entirely by 1991 under a cloud of yet more transatlantic miscommunication.

But it was the other big initiative of 1988 that was closest to Wild Bill Stealey’s flyboy heart. Frustrated by the limitations of the personal computers which ran his beloved flight simulators, he concocted a scheme to build his own hardware in order to do them justice. Gene Lipkin, a former executive with the original Atari, took charge of a project to build coin-op versions of MicroProse’s games for arcades, beginning with F-15 Strike Eagle, their most successful game of all. The arcade version of that game, which was unveiled in 1990, could draw 60,000 polygons per second to its huge 27-inch screen at a time when the average PC-based MicroProse simulator was pushing about 1500. But, impressive though the hardware may have been, the whole project was profoundly ill-conceived from a business perspective. Like its microcomputer equivalent, the arcade version of F-15 Strike Eagle was a deep, fairly realistic game that would require some time even to fully understand, much less master. That was fine for home-computer software, but totally at odds with the quick thrills typically offered by arcade quarter-munchers. The extended play time, the complex missions which the player had to earn the right to play… none of it made any sense whatsoever as an arcade game. Even the First Gulf War, which was being televised live every night on CNN and creating a voracious appetite for flight simulators on home computers, couldn’t save it. It flopped.

As all of these misbegotten ventures ran their course, the losses piled up at MicroProse: $1.4 million in 1988, $300,000 in 1989, $600,000 in 1990. In 1991, Stealey decided that the best way to clear all of his failed ventures off the books and start moving forward again was to launch an IPO. On October 3, 1991, just as Meier and Shelley and their helpers were in the midst of the final mad scramble to finish Civilization, MicroProse issued 2 million shares at an initial price of $9 each. It was, to say the least, an unconventional move; companies normally launch IPOs when things are going well, not when they’re going poorly. [3]MicroProse had become a distributor of “affiliated labels,” smaller publishers who paid for access to their distribution network, in the late 1980s. In the run-up to the IPO, trying to make their bottom line look better, they abruptly stopped paying such labels for the games they sold. Among the publishers that were nearly undone by this move was Legend Entertainment. In light of episodes like this, it’s perhaps not a big surprise that, while Sid Meier was universally liked and respected, Bill Stealey’s reputation within his industry was, at best, mixed. For MicroProse, it would prove only the most short-lived of bandages on a series of financial wounds Stealey would only continue to inflict on his company.

Nevertheless, Civilization did come out that December, in a nice-looking box, with a fat manual (largely written by Shelley) and a pull-out insert for that magnificent Advances Chart. No one, of course — not even the game’s designers or its most zealous devotees among MicroProse’s creative staff — had any idea of what it would ultimately come to mean for its industry or its art form. Certainly no one could have dreamed that Civilization would still be going strong as I write these words more than a quarter of a century later, that it would become the sort of game quite likely to go on for as long as our own civilization exists to sustain it. “We knew it was a fun game,” remembers Meier, “but there had been no historical example of a [computer] game that had that kind of longevity at that point. We didn’t have a sense that this was going to be so different from the other games we had made. We thought it was good and creative and had new ideas in it, but had it flopped we would not have been shocked.”

Following the lead of its designers, gamers at large for the most part regarded Civilization as merely the latest release from the highly respected Sid Meier, albeit perhaps one with an unusually intriguing premise. Most of the initial reviews showed no inkling of the game’s ultimate importance, although they were universally positive. The one reviewer who did seem to grasp the game’s timeless quality was Alan Emrich. Writing in his usual affected style for Computer Gaming World, the journal of record for hardcore strategy gamers, he concluded his review by saying that “a new Olympian in the genre of god games has truly emerged, and Civilization is likely to prove itself the greatest discovery in computer entertainment since the wheel.”

But most importantly, Civilization sold quite well following its release, spending several months among the top ten sellers in the industry, rising once or twice as high as the number-three spot. Whatever he personally thought of Sid Meier’s recent esoteric project choices, Wild Bill Stealey couldn’t complain about the commercial performance of this, his latest effort, which earned back all of the money it had cost to make it in fairly short order.

And then, something else started to happen. After those first several months were over, when sales of any other computer game could normally be expected to fall off a cliff, they did no such thing in the case of Civilization. Month after month, Civilization kept right on selling. It became that rarest of beasts in what was becoming an ever more ephemeral, hits-driven industry: a perennial. Over the course of its first four and a half years on the market, it sold 850,000 copies, while becoming a huge influence on a whole new generation of ambitious turn-based grand-strategy games. Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley had never made a sequel in their careers, and never had any inkling that this latest game of theirs would spawn a franchise, much less a genre — much less, for some players, a veritable lifestyle. But when MicroProse bowed to their customers’ demands and belatedly returned to the well in 1996 with Civilization II, the die was well and truly cast. Publishers, designers, and technology might come and go, but Civilization was forever.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K A Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, Game Design: Theory & Practice by Richard Rouse III, and Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Game People Play by Morgan Ramsay; PC Review of August 1992; A.C.E. of May 1990; Computer Gaming World of January 1988, June 1989, September 1990, December 1990, November 1991, December 1991, and April 1992; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin from October 25 1991, March 27 1992, June 5 1992, and August 14 1992; Soren Johnson’s interviews with Bruce Shelley and Sid Meier. My huge thanks go to Soren for providing me with the raw audio of his Sid Meier interview months before it went up on his site, thus giving me a big leg up on my research.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Soren Johnson, who many years later worked as co-designer of Civilization III and lead designer of Civilization IV, remembers Meier loaning him some reference books near the beginning of his involvement with the franchise, telling him that they might be good resources to use in refining or expanding the Advances Charts of the earlier games. Flipping through the books, he noticed underlined phrases like “ceremonial burial.” With a start, he realized that he had in his hands a history book that had itself become a piece of history: one of Sid Meier’s original sources for the original Civilization. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Dan Bunten began living as the woman Danielle Bunten Berry shortly after the publication of Global Conquest. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

| ↑3 | MicroProse had become a distributor of “affiliated labels,” smaller publishers who paid for access to their distribution network, in the late 1980s. In the run-up to the IPO, trying to make their bottom line look better, they abruptly stopped paying such labels for the games they sold. Among the publishers that were nearly undone by this move was Legend Entertainment. In light of episodes like this, it’s perhaps not a big surprise that, while Sid Meier was universally liked and respected, Bill Stealey’s reputation within his industry was, at best, mixed. |