Personally, I’ve never been one to imagine small things.

— Jane Jensen

When Jane Jensen first said that she would like to make a dark-tinged, adult-oriented mystery of a Sierra adventure game, revolving around an antihero of a paranormal detective named Gabriel Knight, her boss Ken Williams wasn’t overly excited about the idea. “Okay, I’ll let you do it,” he grumbled. “But I wish you’d come up with something happier!”

What a difference a year and a half can make. At the end of that period of time, Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers was a hit, garnering vive la différence! reviews and solid sales from gamers who appreciated its more sophisticated approach to interactive storytelling. Rather than remaining an outlier in the company’s catalog, it bent Sierra’s whole trajectory in its direction, as Ken Williams retooled and refocused on games that could appeal to a different — and larger — demographic of players.

There was no question whatsoever about a sequel. In January of 1994, just six weeks after the first Gabriel Knight game had shipped, Jane Jensen was told to get busy writing the second one.

She was more than ready to do so. In fact, she already knew exactly what she wanted the second story to be: a tale of werewolves, Richard Wagner, and Ludwig II, the (in)famously eccentric last king of an independent Bavaria. She’d developed a fascination for all of these subjects when she’d spent nine months living in Germany just before coming to Sierra. “It was initially the plot for the first game,” she says, “but when I started looking at it, I felt I needed to go back further in the characters’ history.” Now, having told how a New Orleans pulp-novel writer, bookstore owner, lady’s man, and general layabout named Gabriel Knight became a “Schattenjäger” — a “shadow hunter” of things that go bump in the night — she was ready to send him to Germany to face The Beast Within.

Very early on during the design phase if not right away, The Beast Within was earmarked to become the second of a new generation of Sierra adventures, which were to be built around filmed snippets of live actors. It was an enormous change from the hand-painted pixel graphics of the first game, but Jensen was, as she says, “all for it.” Although shooting on location in Germany would have been her dream scenario, there was no way the budget would stretch that far. Instead her actors would have to perform in front of a blue screen that would be filled in with computer-generated backgrounds after the shoot, as was the norm for these kinds of productions.

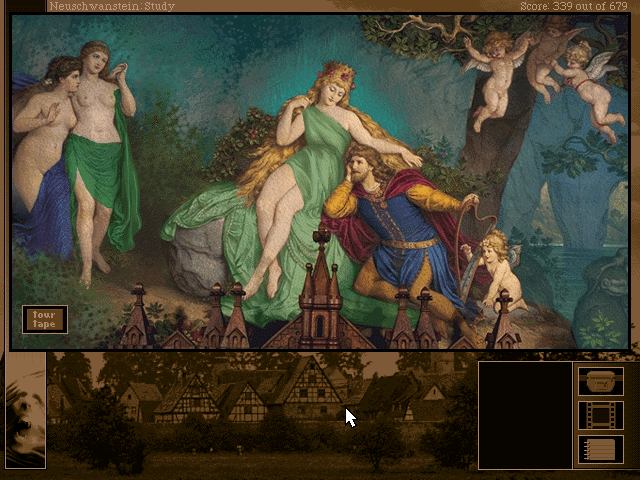

In lieu of taking the whole project to Germany, she did convince management to allow her to bring a piece of that country to Sierra’s offices in Oakhurst, California. During the second half of 1994, she and other Sierra staffers made three separate trips to Germany, spending more than a month there in all, painstakingly photographing among other places Munich’s city center, the Wagner Museum in Bayreuth, and Neuschwanstein, “mad king” Ludwig’s fairy-tale castle. These photos were then touched up as necessary to serve as the scenery behind the actors. This in itself represented a marked change in approach from the 3D-modeled backgrounds employed by Phantasmagoria, Sierra’s first game of this type. It was a wise choice for this project; while the mixing of media is by no means always seamless, the photographic look gives The Beast Within an unusually strong atmosphere of place. The hazy, slightly washed-out look of the backgrounds — an unavoidable byproduct of the state of digital imaging at the time — contributes to rather than detracts from the mood. “We were lucky in all three of the trips over there in that it was fairly overcast, so we didn’t have any harsh, direct lighting on most of the things,” says Nathan Gams, the project’s creative director and chief photographer. “We wanted a soft, gloomy kind of European spring feel. It kind of reflects the alien place where Gabriel is at this time.”

With the background images duly captured, it was time to think about the foreground actors. The budget only allowed for the Screen Actors Guild minimum wage, which precluded “name” stars such as Tim Curry and Mark Hamill, both of whom had provided voice acting in the first game.

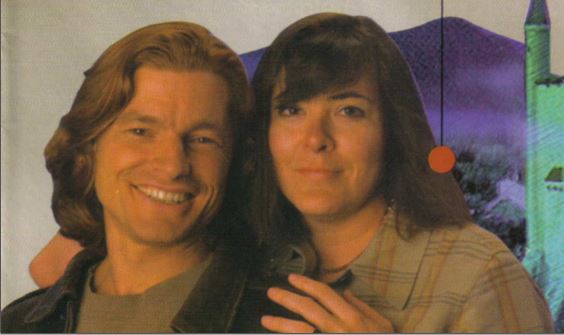

Sierra wound up casting in the role of Gabriel one Dean Erickson, a 36-year-old with an interesting story behind him. He had been working in finance on Wall Street at age 30, when he suddenly decided that he wanted to be an actor instead, despite having never performed in so much as a high-school play prior to that point. Six years on from that decision, his chief claim to fame was a bit part in three episodes of the sitcom Frasier. Jane Jensen was initially uncertain that he had the chops to play the role of Gabriel, even though in appearance he was “spookily like what I would have thought the character would be”: “It was more a matter of being sure that he could play all the different faces of Gabriel Knight.” But she allowed herself to be convinced in the end.

“I would like to be the lead guy in major features,” Erickson himself said at the time, “and hopefully my performance in this will lead someone to believe that I can help carry a movie.” Hope does tend to spring particularly eternal in Hollywood. In the world of reality rather than Hollywood fantasy, a much older and perhaps wiser Dean Erickson would come to look back on The Beast Within as the best that things ever got for him as an actor, what with “making SAG scale for three and a half months in an idyllic setting under controlled conditions with nice people.”

It was intense in that we shot fairly quickly, only one or two takes per shot. But we were mostly shooting on an air-conditioned sound stage in a beautiful part of the country during the summer near a lake. We worked mostly nine to five, Monday through Friday, so it was about the best situation one could have as an actor. It truly couldn’t have worked out better, other than maybe getting work afterwards.

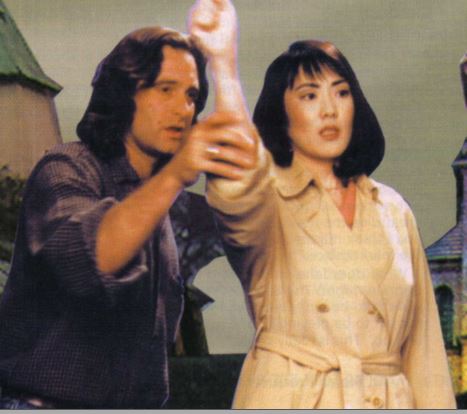

The role of Grace Nakimura, Gabriel’s strait-laced research assistant and potential love interest, went to Joanne Takahashi, a stage actress and print-advertising model who was also trying to break through in Hollywood. Meanwhile a Polish actor named Peter Lucas would all but steal the show in the role of the darkly enigmatic Baron Friedrich Von Glower, who slowly emerges as the principal antagonist of the story. The cast was rounded out with more than 40 other speaking parts, all recruited like the leads from the ranks of Hollywood hopefuls flashing their SAG membership cards.

Sierra’s original choice as director was an in-demand music-video maker named Mark Miremont, whose grainy, hyperkinetic productions can be credited with inculcating much of the look of MTV during the grunge era. It would have been intriguing indeed to see what he might have done with The Beast Within. But those plans fell through at the last minute, and Sierra instead hired a less distinctive aesthetic personality named Will Binder, a graduate of UCLA film school who had recently been serving as a director’s assistant in such films as The Scent of a Woman.[1]This résumé would later lead to my favorite ever interview opening, from the adorably fannish website Adventure Classic Gaming: “You have worked with some of the best actors in the business — Al Pacino, Michael J. Fox, Bruce Boxleitner, Mira Furlan, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and of course, Dean Erickson and Joanne Takahashi.” Two of these names are not like the others…

Before talking about how any of these folks performed, it’s only fair that we take a moment to appreciate just how awkward this style of “film-making” really was. The difficulties and constraints extended even to the clothing worn by the cast; the chroma-keying process which allowed the programmers to superimpose the live actors over the digitized photographic backgrounds came complete with many restrictions, as noted by costumer Marcelle Gravel:

There are a lot of limitations in terms of colors. [We can’t use] anything that is close to blue or anything white that can reflect the blue, or any green that has a little blue in it. Sometimes black doesn’t work because when it gets wrinkled, it reflects.

So the wardrobe has to be very safe. Gabriel was supposed to be wearing a black jacket, a white tee-shirt, and blue jeans — an American uniform. It is James Dean, Marlon Brando, all those people. And when I started Gabriel, I can’t use black, I can’t use white, I can’t use blue. So what am I going to do to create that effect?

He ended up wearing green. Since he’s got the red hair, I think the green has a good effect on him.

The blue screen also meant that much or most of the evolved language of film had to be tossed. The camera wasn’t allowed to swoop or soar; it had to remain stock still if the computer-generated backgrounds were to look coherent after they were inserted. Thus the scenes had to be staged and blocked like live-theater productions which happened to perform for a camera rather than a live audience.

Making an interactive story, in which scenes could occur in many different orders, played havoc with the actors’ ability to inhabit their roles. Will Binder:

[The player] can jump around during the game at any point, so the actor has to have a neutral emotion at the start of each scene. [The scene currently being filmed] could [be] before a big scene happened or could [be] after a big scene.

In a regular movie, you would like to tell [the actor], “Okay, this just happened: you just broke up with your girlfriend.” Or, “An hour ago you found out some information about a person you have been dealing with.”

In the game, [the player] can go anywhere [they] want. So there is no linear progression.

Joanne Takahashi:

With this shoot, you are taking so many different paths you are not sure where the character is going. It is a challenge.

I am just feeling it through and letting things come to me as I go along. It was something to adjust to because a lot of what actresses do is inspired by what they are feeling. That was a difficult challenge, but that was a requirement on this kind of project.

Most of the actors were not technically oriented, and had little concept of how the scenes they were shooting would be cobbled together into a coherent final product. Certainly there was nothing like the daily rushes of conventional filmmaking, which help actors understand how a production is coming together while the shoot is still progress. The actors working on The Beast Within were swimming blind in unknown waters.

Keeping all that in mind, then, how did the actors do?

Dean Erickson is a rather counterintuitive case in some ways. On the one hand, he badly misses the mark of the Gabriel Knight that Jane Jensen likes to describe. Far from a cool lady-killer, he radiates discomfort in his own skin virtually every moment he spends onscreen; he’s forever sighing and twitching and glancing nervously away as if looking for direction (which he quite possibly is, come to think of it), coming across as a guy for whom propositioning a girl comes as naturally as foreign languages. (American to the core, Gabriel has managed to avoid picking up a word of German during the months he’s already spent in the country.) Needless to say, nothing about this performance will convince you that Erickson is Hollywood leading-man material.

And yet Erickson’s take on Gabriel kind of works despite itself. His discomfort before Will Binder’s cameras mirrors that which any born-and-bred New Orleanian would feel after being transplanted to such an utterly foreign clime as southern Germany. For all of Erickson’s manifest limitations as an actor, I have to say that I like his Gabriel more than I do the one Tim Curry voice-acted in Sins of the Fathers. He’s relatable in his way, and, if he doesn’t exactly radiate masculine virility, nor does he come across like a member of the #metoo Most Wanted brigade, as Curry’s Gabriel too often did. He’s not bad company on the whole, once you get used to his incessant fidgeting. In achieving this much, he fulfills the first and most important criterion of any good adventure-game protagonist.

But Joanne Takahashi’s Grace is, alas, less likeable. This is a problem in that Grace steps up to almost equal time with Gabriel in this second game; the player controls her rather than Gabriel through two and a half of the game’s six chapters. Her apparently unrequited affection for Gabriel and jealousy of his beautiful German secretary Gerde are doubtless intended to be endearing, but are written and acted with all the subtlety of a wrecking ball to the head. Whether because she’s got them old lovesick blues or because she’s just made that way, Grace is bitchy toward everyone and everything she encounters for much of the game. Only toward the end, when she’s finally accepted that Gerde isn’t after her man and that Gabriel really needs her help, does she start to lighten up a bit. But even then, the actress who plays her remains stiff as a board.

Peter Lucas by contrast gives by far the most natural performance, as Baron Von Glower, the libertine leader of a mysterious big-game hunting club which Gabriel stumbles upon in the course of his investigations. Every time he appears, he lights up the screen with his romance-novel looks and his enticing aura of danger; his scenes with Gabriel flare with far more sexual tension than Gabriel ever strikes up with Grace. Lucas’s onscreen performance stands out as one of the best of the entire full-motion-video era of gaming — granted, not an overly high bar to clear, but we should give him his props nevertheless.

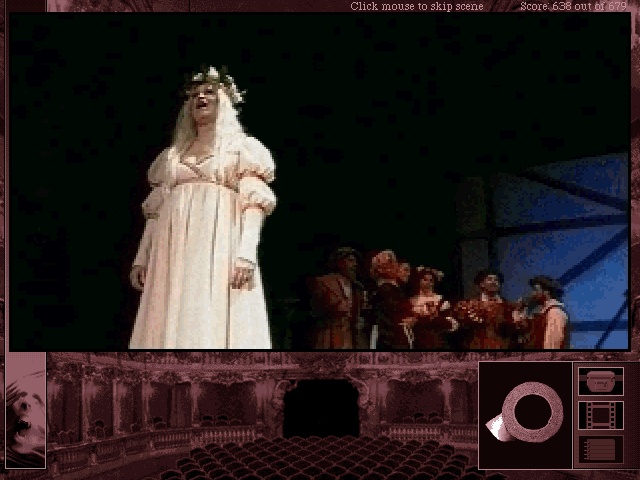

The Beast Within took over Sierra’s new Oakhurst sound stage in May of 1995. Filming there lasted almost four months in all. At its conclusion, the crew moved to Seattle for a few days to shoot the game’s climactic scenes on location in the city’s opera house, complete with many of the local opera company’s own players. Here the constraints imposed by the game’s peculiar technological stew fell away, and Will Binder got to shoot something resembling scenes from a proper movie. He was a lucky guy; very few other full-motion-video productions from the 1990s ponied up for a full-fledged location shoot.

Coming to this article, I had fonder memories of The Beast Within than Sins of the Fathers, and I was curious to find out whether that impression would hold up. I was gratified that it generally did. The game is as shaggy as its namesake even if one looks beyond the uneven acting, being full of unnecessary stumbling blocks in its interactivity that prevent me from giving it a full-throated recommendation here or making a place for it in my personal Hall of Fame, where fairness to the player is a prerequisite. But it’s a fascinating piece of work all the same, created as it was just at the apogee of that window of time when interactive narratives starring “real” actors were considered the necessary future of gaming by big companies like Sierra — so much so that they were building million-dollar sound stages for themselves to churn them out with the alacrity of any Hollywood studio. Jane Jensen would never get a chance to work on a scale like this again. And it must be said that she made the most of it: the overweening ambition of The Beast Within — the sheer grandiosity of it all — makes it a sight to behold. This is a computer game for which an opera was composed, for God’s sake. Everyone involved with it was unabashedly shooting for the moon.

The game opens several months after the conclusion of Sins of the Fathers, when a very reluctant Gabriel has moved into his ancestral castle in Germany to take up the family business of shadow-hunting. Meanwhile Grace has been left behind in New Orleans to run his old bookstore.

One dark night, a group of German villagers straight out of Hammer Horror central casting knocks on the front door of Gabriel’s castle. “We have come for the Schattenjäger,” says their leader. It seems that a little girl living in another small town near Munich has been killed — by, the visitors believe, a werewolf. (“At least she died quickly,” says the village patriarch to her grieving father, a line so hilariously tone deaf that one has to assume it was intended to be funny.) Gabriel has his doubts, but he agrees to take the case. His investigations will eventually lead him to the hunting club led by Baron Von Glower.

When Grace learns of the case, she hightails it to Germany, but doesn’t join up directly with Gabriel. Instead she occupies herself with research on the real or mythical history of lycanthropy. She learns that Ludwig II, king of Bavaria from 1864, seems to have become a werewolf himself while still a young man, and that this may account for much of his legendarily strange behavior. Further, she discovers that he told his friend Richard Wagner of his plight, prompting the latter to compose a magical opera which he hoped would be able to drive out the curse. But he was unable to complete it before Ludwig died under mysterious circumstances in 1886 — he had become a persistent irritant to the new, Prussia-dominated united Germany, making his death fodder for all sorts of conspiracy theories — and the opera was never performed. What there was of it was lost, seemingly forever — until the dogged Grace digs it up again. She soon has urgent need of it, as Gabriel has by now gotten himself infected with the curse.

All of this is mind-bogglingly ridiculous, of course, but the game leans into it with a commitment that would make Dan Brown proud, and darned if it doesn’t do a pretty good job of selling it. The Beast Within is nothing if not a slow burn. Gabriel doesn’t meet his first indubitable werewolf in the flesh until over two-thirds of the way in, while Grace’s chapters involve little more than poring over musty books and museum exhibits, giving them at times more of the flavor of an educational CD-ROM than an adventure game.

Much of Grace’s time is spent touring Neuschwanstein Castle, complete with the obligatory tourist audio guide.

Clearly Jane Jensen was touched by the wistful, sorrowful life of Ludwig, enough so as to make it the thematic bedrock of her game. She saw parallels with a certain modern eccentric whose days would also end in tragedy and controversy:

He was a real misfit, never in sync with the world. He lived in a fantasy world, and because he had a lot of money, he could surround himself with fantasy, not unlike Michael Jackson now.

As time went on, he got more and more beaten down by the world. His relationships never worked out, and he was always disillusioned. He was a very sensitive soul who was just hurt by everything, who kept retreating and withdrawing.

When he was young, he was very much a Prince Charming type. And of course his end was very tragic. So I just think it is a very beautiful, sad story of a life.

Grace’s historical research and Gabriel’s more active investigations meet only in the sixth and final chapter of the game, when the former arranges a public premiere of the lost opera in order to cure the latter of the affliction he’s picked up. The audacity of this bit is almost unbelievable. Not only did the game’s soundtrack composer Robert Holmes — also Jane Jensen’s husband — dare to write an opera, he had the colossal cheek to make it a lost Wagner opera. It took him “about a week,” as he remembers it. (One has to assume that the real Wagner devoted somewhat more time to his masterworks). I’m in no way qualified to judge the worthiness of Holmes’s opera, but I must assume it to be dire enough to send aficionados running from the room with their hands over their ears. Nevertheless, here’s to ambition. One certainly can’t accuse this game of pulling any of its punches.

All of its interest in place and history can rather overshadow its bona fides as a work of horror. Much of the time, it’s more eerie than terrifying, more melancholy than thrilling; suffice to say that it lives in a place far removed from the schlocky sensationalism of Roberta Williams’s Phantasmagoria. When the time finally does come to confront werewolves nose to snout, however, The Beast Within doesn’t disappoint. There’s one scene in the penultimate chapter — anyone who’s played the game will know which one I’m talking about — that’s unsettling enough to give you nightmares. While it’s easy enough to laugh off Phantasmagoria‘s cartoonish execution scenes, you won’t be laughing at this one. If the climax in the opera house is ironically less horrifying than what comes immediately before it, fair enough; one scene like that should be enough for any game.

All of which is to say that The Beast Within is a richly textured, admirably complex work of fiction in many ways. At its best and judged in the context of its time, it was one of the most impressive interactive narratives yet attempted on a computer by 1995. But alas, it isn’t always this best version of itself. What with so much love having been so clearly poured into the game from so many different quarters, I can’t help but wonder why Jane Jensen couldn’t manage to make it just a little bit better. Mixed in with all of its rarefied intellectual and thematic aspirations is plenty of B-movie amateurishness. The language barrier gets erected and torn down willy-nilly, depending on whether Jensen wants to make a plot element out of it or not at any given instant; particularly amusing is the Schattenjäger library in Gabriel’s family castle, consisting of a bunch of Medieval texts helpfully written in modern English. There’s no reason that plausible ways around the language problems couldn’t have been built into the game’s puzzle structure, doing much for its sense of mimesis and potentially even for its character-building in the process. (Perhaps Grace needs to enlist the help of the hated Gerde to translate?) Similarly, the game’s timeline makes no sense whatsoever. Gabriel and Grace’s separate investigations overlap with one another in ways that would only be possible if one or both had a time machine to hand.

These may strike some as the pettiest of niggles, but the fact is that continuity matters in the crafting of believable fictions of any stripe. No credible book-publishing house or film studio would allow a story to go out in such a state as this one. Plot may stand at a lower rung on the artistic totem pole than character or theme in the minds of many, but even most of these will acknowledge that a coherent plot is a necessary prerequisite to those other things.

The Beast Within has some really good puzzles that stretch the interface beyond the typical “use item X on hotspot Y.” One, for example, requires you to construct a fake telephone message by splicing together snippets of recorded speech.

And then there is the interactive design. Jane Jensen resisted any pressure that may have come her way to dumb down The Beast Within in the manner of Phantasmagoria: her game is full of real puzzles worthy of the name, in some cases pretty good ones. In fact, it fares considerably better on this metric than Sins of the Fathers. Nevertheless, there remains a smattering of bad design choices that serve to pull you out of the game every time you feel yourself on the verge of becoming truly immersed in its world. A few of the puzzles hinge on the sort of moon logic for which adventure games have been so often justifiably criticized. (Using a cuckoo clock on a potted plant? Really, Jane?) Even one example of this sort of thing can be ruinous to the player’s experience, in that it destroys her trust in the game’s interactive design at the same time that it demolishes the integrity of its fiction.

In Grace’s chapters, Jensen lays claim to the dubious status of being the inventor of the hidden-object genre: you have to pixel-hunt your way through several big areas, looking for that one tiny thing you overlooked the last dozen times through. You see, this game really, really wants you to know everything possible about Richard Wagner and King Ludwig II: it won’t let the plot proceed until you’ve clicked on every last hotspot on every last detail in every last musty little corner of their respective museum and castle — in a few cases twice. Finding it all can be a challenge even if you’re playing directly from a walkthrough.

And when we get to the big finale, Jensen falls into the common trap of assuming that the ending of an adventure game ought to be much harder than what has come before. (In reality, the opposite is true; the player has already done lots of thinking during the mushy middle, and now just wants an exciting climax followed by victory, with a minimum of fuss.) One key puzzle here hinges on manipulating an object in a way that the interface has never allowed before and never even hinted was a possibility. And the literal last action you need to do in the game is a tricky exercise in perfect timing and precise clicking that’s also out of keeping with everything that’s come before, so much so that you could easily assume you’ve missed something and waste hours looking for it.

But regular readers have heard similar litanies of design sins from me many times before, so I won’t belabor these issues further here. The Beast Within is yet another checkered product of Sierra’s creative culture, which, in marked contrast to such other adventure specialists as Infocom, LucasArts, and Legend Entertainment, never emphasized outside play-testing or even serious discussion of the craft of design in the abstract. Interesting and engaging as it is in its present state, it could have been so much better, if only a process had been put in place to make it better. Whatever the merits of his year-to-year choices as a businessman, Ken Williams’s failure to do so — a byproduct of his personal disinterest in actually playing his company’s games — will always stand as his biggest single lapse in my book.

Wagner’s Lost Opera, the grand finale to The Beast Within. Most games, then and since, have tended to front-load their most impressive scenes so that everyone — not least potential buyers — can see them. This one’s willingness to hold off until the very end says something, I think, about the spirit of grandiose (operatic?) idealism that marked the whole project.

The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery shipped on six CDs less than a week before the Christmas of 1995, half a year after Phantasmagoria had been greeted with huge sales and much mainstream-press attention. Everything about this latest release reflected the current ebullient mood at Sierra, where everyone was convinced they were about to truly hit the big time, with a vastly expanded customer base. For example, the box was careful not to say that this was “Gabriel Knight 2,” for fear of scaring away that new generation of buyers, who might not be keen on starting a series in the middle and might be even less keen on playing an “old-fashioned” game like Sins of the Fathers.

Indeed, even Sierra’s new fictional genre of choice reflected the new focus on the mainstream. Horror was a less stereotypically nerdy ghetto than fantasy or science fiction, yet one that was still fairly well-suited to adventure-game modes of interaction. So, after never touching the genre for the first decade and change of their existence, Sierra was now all over it. Three of the five domestically-developed adventures they released in 1995 were horror games. (The third companion to Phantasmagoria and The Beast Within in this respect was the lower-profile Shivers, a solitary Myst-style first-person puzzler created by a breakaway team at Bright Star, Sierra’s educational-software subsidiary.)

In comparison to the adventure-lite Phantasmagoria, The Beast Within was perhaps a wolf in sheep’s clothing: it was, as we’ve seen, a game that evinced a full measure of respect for its audience’s collective intelligence, with challenging puzzles and complex present-day and historical mysteries to tease out. Still, there’s little reason to believe it was because of this that it failed to sell anywhere near as well as its predecessor. The mainstream magazines and newspapers that had covered the older game as a curiosity showed little interest in the newer one; ditto the many people who had bought Phantasmagoria strictly to show off their new multimedia computer systems. That left only the traditional adventure market, the same people who had bought Sins of the Fathers. It seemed that Sierra was suddenly back to square one.

This state of affairs was, to say the least, deeply disconcerting to everyone there, as they all found themselves having to adjust their paradigm of gaming’s necessary future at lightning speed. Sierra programmer Greg Tomko-Pavia expressed the collective confusion in a contemporary online interview whose frankness presumably wouldn’t have endeared it to his managers:

I must say that I’m surprised Phantasmagoria has done so well. Presently, we’ve sold over 700,000 copies — more than any other Sierra game. I can’t account for it. In my opinion, Phantasmagoria suffered from weak writing, acting, and direction. I don’t understand why Gabriel Knight 2, to my mind superior in every detail, isn’t doing nearly so well. What do I know? I just write code!

At the time of The Beast Within‘s release, Sierra was already filming their third big interactive horror film on their Oakhurst sound stage, a sequel-in-name-only to Phantasmagoria subtitled A Puzzle of Flesh. Its garish grindhouse aesthetic made its two boundary-pushing predecessors look downright prudish — which was, one supposes, further progress of a sort. But it would prove the last production of its type. Once it too had disappointed in the marketplace, its feverish courting of controversy having largely come up dry, the facility Sierra had built with such pride and at such expense would be used only occasionally, for 3D motion captures and the like. It was now clear that gaming writ large was going in a different direction entirely, leaving the sound stage a fork in a world of soup.

As for Gabriel and Grace: against all the odds, they would return for one final game, but that would be a more constrained production than this one, using one of the 3D engines that were taking over the industry. There’s a world-weariness about that game — a sense of existential despair on the part of its creators that’s almost palpable when playing it — that you won’t find in this one, which was created by a team who saw only limitless potential everywhere they looked. The Beast Within is the product of a rare moment when the creative and the commercial impulse seemed united as one. For all its frustrating infelicities, it positively soars with its makers’ enthusiasm, with their bracing willingness to just try. Neither Jane Jensen nor any of the rest of them realized how lucky they were to be given the time and money to do so.

Six months after the release of The Beast Within, Roberta Williams, who was always the bellwether of the current creative direction of Sierra, gave a new verdict on the current state of adventure games that contradicted everything Sierra had been saying and doing for the past couple of years:

I believe adventure games have now gotten too plot-heavy. Not just ours, but also a lot of our competitors’ games. I think game designers need to get back to the game and forget all this wanna-be-writer-and-director stuff. They don’t realize people just want to play a game. They want to have control over what happens. Video clips are fine — if they’re very short, to the point, concise, and then… get out of there.

The times, they were still a-changing.

(Sources: the books Influential Game Designers: Jane Jensen by Anastasia Salter and The Beast Within: Official Player’s Guide by Corey Sandler with Jane Jensen; Computer Gaming World of November 1995 and February 1996; Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of Fall 1994, Spring 1995, Fall 1995, Holiday 1995, Spring 1996, and Summer 1996. Online sources include Anthony Larme’s interview with Greg Tomko-Pavia, “The Making of… the Gabriel Knight Trilogy” at Edge Online, Andrea Santorio’s interview with Jane Jensen, Martin Bourassa’s interview with Dean Erickson, Jane Jensen and Robert Holmes’s appearance on a Reddit “Ask Me Anything,” and Ingrid Heyn’s interview with Will Binder.

Now re-titled with the numeral Sierra once eschewed, Gabriel Knight 2: The Beast Within is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | This résumé would later lead to my favorite ever interview opening, from the adorably fannish website Adventure Classic Gaming: “You have worked with some of the best actors in the business — Al Pacino, Michael J. Fox, Bruce Boxleitner, Mira Furlan, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and of course, Dean Erickson and Joanne Takahashi.” Two of these names are not like the others… |

|---|

Sol_HSA

August 20, 2021 at 10:16 am

The use of filmed actors instead of drawn (or 3d) characters in the beast within undelined, for me, how much of an a-hole a generic adventure game character is.

Take the scene where you go to someone’s office (whom you know nothing about, or suspect of any wrongdoing), ask them to fetch you some water to get them out of the office, and then go through their stuff.

For a virtual character that’s understandable, in an adventure game logic kind of way, but to see an actual actor do it? Ummm..

Niccolò

August 20, 2021 at 10:45 am

Great article as always! I played this game a few months ago and while I agree that the writing is *way* better than most adventure games, I was decidedly underwhelmed by the actual puzzles and gameplay. The world just isn’t very interactive, navigating it is excruciatingly slow, a lot of locations are mostly empty, and puzzles that feel interesting but not completely arbitrary are few and far between. Personally, I liked the sequel (Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned) a LOT better in that regard: conversations, locations, puzzles and general interactivity felt much richer and deeper. It felt much more like a “real” game, to me at least.

Petter Sjölund

August 20, 2021 at 1:08 pm

I wouldn’t call the writing in The Beast Within better than the average LucasArts game. In fact I can’t think of any LucasArts game, The Dig included, that doesn’t have better written dialogue. The fact that The Beast Within takes place in the real world, however, and is so ambitious and well researched, makes it in many ways more interesting than those games.

JackyT

August 26, 2021 at 2:09 pm

I loved this game. In fact I had an hour-long discussion in Bad Ischl with an American author of a book on Ludwig at his book launch. All my information was based on ‘The Beast Within’!

Peter Olausson

August 20, 2021 at 12:20 pm

“Frasier” was easily spotted. :-)

As for the opera, how much of it do we see/hear? Perhaps Wagner could have created a work of similar length in “about a week”? Creating a Wagner replica sounds very daring, to the point that you would do it only if you knew exactly what you were doing.

You mention GK(2) shipped just in time for the Christmas buying season. Jensen has mentioned (on Gamespot Designer Diaries) that it arrived in stores on Christmas Eve, which ought to be among the worst days of the year for such a release.

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 5:58 pm

Thanks!

We see about ten minutes of the opera in the game, but what’s there is surprisingly complete: music, libretto, stage set, costumes, singers and orchestra.

I don’t have an exact release date for the game; it’s unfortunately not found in the American copyright registry, whose “publication date” field has been the gift that’s kept on giving for years when it comes to questions like this. Jane Jensen may very well be right, but I wouldn’t just take her word on such a specific data point without corroboration. Not that she would be dishonest — it’s just that memory is a malleable thing, and developers’ awareness of the logistics of distribution is often vague under any circumstances.

Brian Mathews

August 21, 2021 at 2:20 pm

It is too bad we don’t have super accurate writing and release information as we do for the origin of the Ultima series!

I would guess the release and sales records for many books, games, movies, etc., are now irretrievably lost or slowly moldering away in boxes in attics and warehouses…

California Tax Payer

August 22, 2021 at 8:12 pm

Looking at CD timestamps, it looks like December 12, 1995 was the finish date. That would be just enough time to rush duplication and shipping for around Christmas Eve. Most importantly for Sierra Inc, the revenue would hit in the right quarter.

Jimmy Maher

August 23, 2021 at 8:54 am

That’s some solid evidence. Edit made. Thanks!

Don

August 20, 2021 at 12:37 pm

Love your series! In the image captions “ Will Binder directs Joanne Takahasi” should read TakahasHi.

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 5:59 pm

Thanks!

Peter Olausson

August 20, 2021 at 2:32 pm

Regarding “films from the pre-Citizen Kane era” … I don’t know which you have seen, but films like Wings (1927) and All quiet on the western front (1930) have plenty of scenes spectacular in every way — a long, long way from live-theater productions indeed!

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 6:01 pm

Yeah, I put that in just before publishing this piece. Bad decision. Thanks!

Peter Orvetti

August 21, 2021 at 10:06 pm

A fair point, but “Citizen Kane” certainly defined a new paradigm in filmmaking (that most other films still did not reach until at least the mid-1950s).

Martin

August 20, 2021 at 6:45 pm

A couple of questions.

You mentioned SAG a few times at the top. Was it just a choice to use SAG actors or something of a requirement.

Secondly you said the plot was ‘mind-bogglingly ridiculous’. Can you expand on that. Was it Ludwig being a werewolf, the Wagner angle, Grace discovering the opera, all above or someing else?

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 6:59 pm

1. It was, I think, a combination of practicality and aspiration. On the former front: the membership roll of SAG is by far the best tool for finding reasonably competent professional actors quickly and efficiently. On the latter front: Sierra was very invested in the notion of interactive movies, and wanted them to be taken seriously by Hollywood. And Hollywood was and is a SAG town. Without a SAG membership card, you don’t work there. Conversely, hiring SAG actors demonstrated a certain professionalism and seriousness of intent.

2. Reread your list of possible reasons. I think you’ll find you’ve answered your own question. ;)

Lisa H.

August 20, 2021 at 6:52 pm

Wow, this is almost a Sesame Street name for this kind of character. (As far as I can tell, “Von Glower” is not a real name; all the search hits I get are either directly related to this game or are people using the name e.g. as a Twitter handle.)

What is the original text here without all your emendations in brackets? I guess “[The scene currently being filmed]” was “It” and “[the actor]” was “him”, but I’m having trouble figuring out what words you thought were unclear that you changed them to “the player” and “they”, and what was said instead of “be”.

(in the caption of the first video clip) Mass-marketed?

Am I wrong in thinking the old guy calling Gabriel “Herr Knight” the second clip looks familiar from somewhere, or is it just that these central casting guys always look alike?

I haven’t played this game and have no particular intention of doing so. Would someone care to spoil this for me?

Fares.

Peter Olausson

August 20, 2021 at 7:15 pm

I find a few von Glowers in old newspapers, American and Austrian. Never a common name, it has at least existed.

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 7:20 pm

Thanks for the corrections!

The interview quote comes from page 73 of the Official Player’s Guide, which you can find here: https://www.pixsoriginadventures.co.uk/downloads/. It’s quite garbled in the original, and sports some emendations even there that attempt to clean it up, but don’t do a great job of it. To answer your specific questions: 1) “the player” and “they” were “you” in the original, but this can easily be confused with “you” the actor from the previous paragraph. 2) In the case of the “be,” the tense suddenly shifts to the present perfect (“have been”) in the original.

The shocking scene happens when Gabriel comes upon a werewolf that has reverted to human form and is, well, *feeding* on his human prey. You can doubtless find it in many place on YouTube. It happens in Chapter 5 out of 6 — so, toward the end of the game, but not *right* at the end.

ShadowAngel

September 3, 2021 at 8:45 pm

Von Glower is at least a believable name for Germany (i am German) unlike Gerde. That’s simply not a name in use here, instead the correct form would be Gerda. It’s one of the three things that make me laugh, the other being how Gabriel pronounces Königlich-Bayrische Hofjagdlodge (it sounds like he just swallows his tongue half-way through) and in general, all the attempts at speaking german, it even tops the horribly broken german in Die Hard, namely the cop in the police station who is so unfriendly to Gabriel, just because he wants “Liebe” (i think that joke flew over the heads of a lot of non-german speaking people, that Leber, pronounced by Gabriel sounds like “Liebe” (Love) :D )

Kay E. Kuter, probably the only “big” name in this (at least he was in a massive boatload of TV Shows and The Last Starfighter, he’s a “Oh, it’s THAT guy!” kind of actor), does a pretty good job at playing a bavarian though.

I love the game, it’s a lot of fun to play, the story is interesting and of course there’s a lot of nostalgia for somebody who group up around and in Munich.

xxx

August 20, 2021 at 7:05 pm

“A fork in a world of soup” is an amazing turn of phrase. Well played!

Typo: “three episodes of the sitcom Fraser” — it’s “Frasier”.

Jimmy Maher

August 20, 2021 at 7:27 pm

I’m afraid I cheerfully stole that from Noel Gallagher of Oasis fame, who applied it to his brother Liam. (Or was it the other way around? I can never keep them straight. But I *think* Noel is the cleverer of the pair, who would be more likely to say something like that.)

Niall

September 5, 2021 at 8:35 am

There’s an old Irish expression: “If it was raining soup, I’d have a fork.” It would be well-known to folk in the North of England, Noel Gallagher included ;)

Richard

August 20, 2021 at 7:25 pm

I love this game so much. The acting is awful and the plot is weird. I love the atmosphere, and the history you learn, and all the digital photography. I love games where you learn, and I felt good learning about real places and real people. This is a snapshot of what I wish interactive movies had brought to games. Also, this reminded me a lot of the first graphic adventure game I ever played, the CD-ROM version of Sierra’s Lost in Time. That was another game that used a lot of digitized photographs as background images, but only had a few very short video clips. I loved the atmosphere of wandering around the digitized images of the French manor in the first half of that game. I definitely preferred the real world feel of using digital photography as backgrounds in adventure games rather then the pre-rendered background of Myst. I recognize the digital photos are usually uglier and make for a clunkier experience playing the game, but even so, I always felt they drew me in better.

Marco

August 20, 2021 at 7:37 pm

A fair review, which picks up both the good and the bad of this game. I do like adventure games that blend fact and fiction to a point that’s almost unsettling, which The Beast Within definitely scores on. It gets bonus points from me for bringing attention to an often-neglected side of German history (i.e. not the Nazis), and was clearly written as a labour of love in that respect.

The homoerotic subtext also mirrors much literature of the period, especially Dorian Gray.

As you note though, the puzzling is a bit all over the place. I equally remember getting stuck for ages at one point because I hadn’t clicked on one hotspot twice.

The third game takes many of the same ingredients, e.g. lots of pixel hunting for clues, baddies who don’t appear until most of the way through the game, but lacks whatever it was that kept The Beast Within reasonably together and coherent, so collapses into (imo) complete garbage.

Zack

August 20, 2021 at 8:32 pm

Gabriel Knight 2 is infamous in french for one of the worst dubbing in the entire business. During some lines you can hear the recording crew talking in the background, actors looking for their text and repeating lines to get in character, or try to. It has completely eclipsed the actual merits or demerits of the game. In France, if you speak about Gabriel Knight 2, those who know it will know it based on its horrible dub, basically.

William Hern

August 20, 2021 at 9:18 pm

Great article Jimmy!

You wrote: “I’m not aware of any other full-motion-video productions from the 1990s that ponied up for a full-fledged location shoot.”

The X-Files game, released in 1998, was a full-motion-video point-and-click adventure game and had a number of location shoots, including at a former US naval base. Maybe you’ll take a look at it when you get to 1998?

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2021 at 7:36 am

I expected a comment like yours. ;) Thanks, duly noted.

Jan Rydzak

August 21, 2021 at 11:45 am

Seconded, fantastic article!

I would love to read your take on the X-Files game, which I think is criminally underrated for what it aspires to be (and in my opinion achieves). AFAIK the vast majority of the scenes in the game were location shoots with minimal use of rendering. Alas, despite its merits, it ended up getting sucked into the same time warp that was consuming other adventure games by 1998, and the use of FMV was nothing if not anachronistic by that point.

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2021 at 12:18 pm

I haven’t played it yet myself, but I do look forward to it.

Josh Martin

August 24, 2021 at 5:12 pm

Digital Pictures (who we’ve encountered before) did location shoots for some of their games. Ground Zero: Texas was filmed in an actual desert (in California, not Texas) and for Corpse Killer they went all the way to Puerto Rico. American Laser Games did location shoots for some of their popular arcade shooting gallery games like Mad Dog McCree and Crime Patrol. And who could forget the CD-i adaptation of the Florida-set syndicated TV series Thunder in Paradise…

Jimmy Maher

August 24, 2021 at 7:30 pm

Ah, how could I forget Digital Pictures? Thanks!

Harry Kaplan

August 21, 2021 at 3:36 am

A few, small, might-have-been notes. At one point, long ago in an oh-no-it-can’t-be-over-yet galaxy far away, I had a little email correspondence with Dean Ericson. He was making a living as a personal trainer in LA then (look him up, he’s gone on to explore many other things since) but was having very serious back problems. As was I, which is the subject about which we were comparing notes. He mentioned that Jane Jensen had tried to pitch to Sierra (guess that means Ken) a fourth Gabriel Knight game as another FMV that would be written with him in mind, but Ken didn’t bite. I think the supernatural element was to be ghosts, but a very new idea of ghosts that Jane was working through. I know that much later Jane wrote an intro short story for a new GK game, sent out to her fans, based on yet a different supernatural idea, and there’s also a three-part comic book (not hard to find on the Internet) more or less pitching to the world another GK story idea. Activision at that time (and maybe still?) had the legal rights to the character, and Jane’s never-say-die fans put a GK4 petition out there directed at that company. I cheerfully signed it.

Adam M

August 21, 2021 at 4:54 am

Where does Urban Runner fit into the story of FMV Sierra games? It was published under the Coktel Vision label in 1996, according to Moby Games. It looks like it was set in Paris, so I wondered how and why this game was developed and released, in the context of what was happening with Sierra’s FMV productions produced back in Oakhurst.

Jay Friday

August 21, 2021 at 6:52 am

Coktel Vision wasn’t a publishing label, but an old and storied French development house that was acquired by Sierra. Their games were generally very, very French – meaning ambitious and unique, but often failing in a lot of the categories that, say, gaming magazines would use to determine whether a game would be good or not. Their most well known games (and probably most palatable for American audiences) were the Gobliiins series of surreal room escape puzzle games.

As far as I know they remained fairly independent from main branch Sierra, and kept making the games that they were making. I wonder if Urban Runner came from a Sierra directive or not. It definitely fits into the Sierra portfolio of that time more than their games have ever done.

Aula

August 21, 2021 at 7:54 am

“Fraser” should be “Frasier” (and since earlier comments make me think you may have difficulty grasping the error here, the correct spelling is F-R-A-S-I-E-R)

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2021 at 9:35 am

Thanks!

James Henderson

November 27, 2023 at 4:53 am

I know this is two years late, but, Aula, you are a complete asshole. Almost every post from you is rude as hell. It’s not necessary; it’s just a typo. Go take a cold shower.

Brian Mathews

August 21, 2021 at 2:24 pm

“You have worked with some of the best actors in the business — Al Pacino, Michael J. Fox, Bruce Boxleitner, Mira Furlan, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and of course, Dean Erickson and Joanne Takahashi.”

Ooh… totally jumping off thread… but Babylon 5 is due for a rewatch soon!

Ian C

August 21, 2021 at 11:44 pm

That was one of our lockdown shows (we have the DVDs). The special effects of season one are a bit iffy, but the rest of the show holds up quite well. I keep hoping someone will run an image-sharpening machine-learning filter over the old lo-res footage and boost the show’s resolution into the modern era.

Brian M

August 24, 2021 at 10:42 am

That would be cool… although I have a feeling it is unlikely.

Captain Kal

September 2, 2021 at 5:06 pm

There is a Babylon 5 HD version, on Amazon

Buck

August 21, 2021 at 2:56 pm

“I’m in no way qualified to judge the worthiness of Holmes’s opera, but I must assume it to be dire enough to send aficionados running from the room with their hands over their ears.”

So, pretty much like a Wagner opera then.

GeoX

August 23, 2021 at 3:43 am

It’s fair to criticize Wagner for being an anti-Semitic asshole, but as one of the said aficionados…you’re not right. And I realize it’s more or less a joke, but the “lol isn’t Wagner boring jokes” are just lazy and dumb.

(Though okay, granted, fair enough: Parsifal IS kind of boring.)

Buck

August 24, 2021 at 7:51 pm

I was half joking. If Holmes sends people running from the room with his (partial) opera – well, that’s pretty much my reaction to Wagner, so maybe he’s not too far off.

(I really don’t believe in the worthiness of a piece of music. But as far as the game goes, Holmes opera is intended to sound like a lost Wagner piece to players who are probably not that familiar with Wagner, and I assume it does that reasonably well. I tried to listen to it, but I couldn’t stand it for long. It did sound rather modern to my ears, but I think so does Wagner at times).

BTW if something sends you running from the room, it’s probably not boring ;)

Sniffnoy

August 21, 2021 at 4:34 pm

Hi, just a comment on a website issue… it seems like recently something has happened where the text starts closer to the left edge of the “notebook page” than it used to? It doesn’t look right.

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2021 at 8:25 pm

Do you mean in the comments area? I did adjust the margins and indentations recently to make room to nest comments eight instead of five levels deep. The text of the articles should not have been affected, however.

Lisa H.

August 21, 2021 at 9:00 pm

Now that Sniffnoy has pointed it out, I see it too. I think the post text is also affected. The left margin is narrower than the right.

Jimmy Maher

August 22, 2021 at 7:05 am

Okay, I think it should be sorted now. (On most browers, you need to reload the page with the shift key held down to clear the old stylesheet from the cache.) Thanks for your good eyes!

Sniffnoy

August 22, 2021 at 4:38 pm

Ah, thanks!

Emily VanDerWerff

August 21, 2021 at 11:45 pm

Storytelling-wise, the Gabriel Knight games do leave certain things to be desired, but I always admire their crackpot ambition. I wish there were 16 more.

I do think the weird, lugubrious quality of what the games are doing has a surprising amount in common with the eight-episode Netflix streaming season. You can easily imagine The Beast Within, in particular, fitting into that storytelling format, largely as is.

Mike Whalen

August 22, 2021 at 10:35 pm

Great article as always

Take from a New Orleans native:

It’s New Orleanian, not New Orleansian.

Jimmy Maher

August 23, 2021 at 5:05 am

I wondered about that. Thanks!

Dev F

August 23, 2021 at 6:55 am

For all its ambition, one thing that always struck me about Beast Within was how much it was straining against the limits of how much FMV Sierra could comfortably fit into a game, even one that shipped on six CDs. Jensen has talked about how she had to cut two full chapters of material (including one in which the player apparently played as King Ludwig!) early in the development process, but it’s clear that they were still nipping and tucking things right up to the end.

The last-minute cut that stood out to me is late in the game, when Grace gets hold of the letter from Von Glower to Gabriel in which the baron makes his big “join me in werewolfry” pitch. There was so clearly supposed to be a major dramatic scene in which Grace gives the letter to Gabriel and he has to choose, in essence, between Grace and Von Glower. But whenever you try to have Grace give him the letter, she gives a “I’ll do that later” type reply — until the now-or-never moment comes, and when you try to offer him the letter at that point, you get a weird TEXT pop-up that nopes out on the whole idea. Apparently this was something that was still in the game until it was too late to even loop in a single line of new dialogue.

I always thought it was a shame that the team couldn’t have cut some final-disc footage of people walking up and down stairs or trying to hang grates back on the wall to make room for the emotional climax of the story!

Jonathan Badger

August 23, 2021 at 5:57 pm

“‘You have worked with some of the best actors in the business — Al Pacino, Michael J. Fox, Bruce Boxleitner, Mira Furlan, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and of course, Dean Erickson and Joanne Takahashi.’ Two of these names are not like the others…”

Yes, Furlan and Hoffman are sadly no longer with us. That’s what you meant, right? Not something about the talent of the last two, heaven forbid.

Michael

August 23, 2021 at 10:40 pm

It’s interesting to me that no one has commented on how much the acting (at least in the sample clips here) resembles that seen on the soap opera “Dark Shadows.” I suspect that its fanbase (small though it is and was) would find this an enjoyable game as well. Soaps probably face some of the same challenges of having to get actors up to speed from a “neutral” position quickly, although their narrative hinges on the exact opposite expectation that the audience knows all of the history behind each scene in obsessive detail.

Fuck David Cage

August 24, 2021 at 6:57 pm

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Father is my favorite adventure game, but this game fucked it up and the series never recovered. Sins of the Father was set in a mysterious, dark corner of New Orleans filled with mysteries, threats and atmospheric; The Beast within was set in a quaint German village in the daylight with virtually no threats and no tension. Gabriel, Mosley and Grace were memorable characters who mixed cynicism and humor and changed their attitude over time in Sins of the Father; in The Beast within, they were boring, featureless cyphers who were only there to serve the plot. Sins of the Father had plenty of great, challenging puzzles and clever jokes; The Beast within had only a few puzzles and was entirely humorless. Sins of the Father had memorable villains; The Beast within had a generic German stereotype who was not even trying to hide his evil plans.

Harry Kaplan

August 26, 2021 at 8:57 pm

Did we play the same game?

Harry Kaplan

August 26, 2021 at 9:12 pm

Aw, c’mon, Jimmy! I can’t believe you’re snubbing both of the first two Gabriel Knight games in your Hall of Fame. You’re certainly right in your intro when you make it clear that your Hall of Fame is a very personal selection, because I just finished a game that lives there (it shall go unnamed) that must have pulled in a marker with you to be awarded that degree of praise.

Still friends, right?

Ross

September 4, 2021 at 6:35 pm

Tim Curry obviously has the far superior voice, but Gabe in this game has an awkwardness to him that makes the character SO much better. In the first game, he comes off like a genre character written by someone who only has a superficial pop-culture understanding of the genre: that Jensen had this surface-level idea of what traits a Cool Supernatural Detective Story hero possesses but didn’t appreciate the way that professionals at writing the genre balance those traits out to prevent a character from becoming unlikeable. So the Sins of the Fathers Gabe comes off as a cad rather than sexy; stupid rather than aloof; arrogant rather than unflappable. (If you’ve seen Star Trek Lower Decks, it reminds me of a scene where an insecure Boimer tries to make himself look cool by synthesizing all the traits of “cool” clothing into an outfit that is part motorcycle jacket, part letterman’s jacket, covered in gold chains, with a football, one of Gaga’s pink boots and a green Chuck Taylor).

In The Beast Within, the fact that Dean Erickson’s awkwardness constantly undermines Gabe’s try-hard coolness makes the character work better.

Niall

September 5, 2021 at 8:27 am

I was a big adventure gamer in my youth, but lost interest in my mid-teens, around about the same time as the death of the Amiga. It wasn’t until I went to college and had to purchase my first laptop that I fell back in love with them. And the game that brought me back in, as it happens, was Sins of the Father, which I discovered many years after its release.

Despite its flaws, I’d never played a game with such a sense of place, and such a meticulously researched story.

On finishing it, l hunted out and eventually found a copy of the sequel. Expecting more of the same, as you would, I was horrified to discover the new approach they had taken. I was unaware of this brief, nauseating trend in FMV games (I’m only really finding out about it now thanks to your blog) — I simply couldn’t fathom why someone would think this a better or more practical way to make an adventure game.

So it’s largely to the game’s credit that I persevered and, in the end, really enjoyed it. It’s true that, after being a dislikable bastard in the first game, Gabriel comes across as a more sympathetic character here, and this more sensitive approach works well with the not-so-subtle homoerotic undertones.

Nonetheless, during my play-through, I couldn’t help but think how much better each section would have played as a traditional point-and-click adventure. And now that I realise how much had to be cut, it seems that, had they taken a more conventional approach, this could have been by far the best game in the series.

It’s a real shame Sierra was more keen on chasing a non-existent mainstream adventure game audience than trying to understand the audience it had already built.

Anyway, thanks for the education: the blog is great.

Erik Moeller

November 21, 2021 at 7:40 pm

Small typo: Grace Nakamura -> Grace Nakimura

Just went back and fixed that in my own review ( https://lib.reviews/the-beast-within-a-gabriel-knight-mystery ).

Jimmy Maher

November 21, 2021 at 7:51 pm

Thanks!

BabylonAS

November 13, 2024 at 10:24 am

TL;DR: I’d love to see an article on Babylon 5: Into the Fire, a cancelled game developed at Sierra (based on my favorite TV series Babylon 5) which had the aforementioned Will Binder produce some FMV scenes for.

Long version:

Aside from the second Gabriel Knight game, Will Binder was involved in shooting scenes for the ill-fated Sierra game, Babylon 5: Into the Fire. It was a space combat simulator based on the renowned science fiction TV series Babylon 5 (starring Bruce Boxleitner and Mira Furlan) that I am a big fan of, if that’s somehow not evident from my nickname. The game was cancelled in September 1999 while it was well into development (“months away from release”, as often claimed); out of it, only a playable alpha demo and the soundtrack remain floating around on the Internet.

Not too much information about the project appears to be out there, with some of it likely being completely lost to the 25 years of time that has passed since the cancellation. But with an animated Babylon 5 film having been released last year and a reboot of the TV series in the works, the game and the story of its development, demise, and failed attempt at resurrection is certainly worthy of attention. An article on your site seems to be an excellent way to bring it all together and ensure it won’t be lost into oblivion, on top of being a great addition to your series of articles about Sierra On-Line and its games.

An especially interesting aspect of ItF’s history, which seems to be particularly unexplored, is how Sierra even arrived at making a Babylon 5 space simulator in the first place. I’d love to see it being recovered, if that’s even possible by this point.

As you’ve written in your earlier articles, Ken Williams once decided to stay away from having Sierra make games based on licenses, though that was many years ago. Besides, ItF was being made when Sierra was already owned by CUC, so his opinion might have mattered less anyway.

The space combat simulator genre, heretofore best represented by the work of Origin (Wing Commander) and Totally Games (Star Wars: X-Wing), seems to be a rather new one for Sierra to approach at the time, especially for the original Oakhurst studio, famous for its adventure games. At a first glance, it seems that Dynamix, which was already successful in the aircraft combat simulator genre, is a more relevant match to develop ItF. That said, ItF was to have a rather developed story line which is more related to what Sierra typically did themselves; but on the other hand, Dynamix had made adventure games of its own.

I wonder what influence Christy Marx had on the choice of Sierra as the game’s developer. She had created two adventure games at Sierra before (notably Conquests of Camelot: The Search of the Grail), then wrote a first season episode for Babylon 5 (called… Grail, and featuring a person seeking it), and finally set out to write the B5 themed game at Sierra.

Could it also be that the more experienced Origin and Totally Games studios didn’t want internal competition with their own space simulator franchises?

The later history of ItF, especially its unfortunate end, is better known, thanks in part to an Internet community called FirstOnes which was active back then (and to some extent still exists today, though it suffered greatly; the most interesting content about the game – such as an archive of the game’s original website – is only available through the Wayback Machine). After an accounting scandal at CUC and the sell out to Havas, Sierra had a rough time. ItF’s development was moved to Bellevue when the Oakhurst studio was closed early in 1999, but half a year later, the game was cancelled altogether alongside a couple others. Some of the laid-off employees formed a separate studio and attempted finishing the game, which required them to buy the remaining game assets from Sierra, but by the summer of 2001 they ultimately failed. By that time Babylon 5 itself was waning in popularity as a franchise, with its spin-offs and attempts at extending the story not being successful.

Over the next years, some vestiges of the game and its development surfaced on the Internet, notably the soundtrack by Christopher Franke (which, by the way, had some of its cues reused in a failed Babylon 5 spin-off, The Legend of the Rangers), a bit of script by Christy Marx, and a disk ISO of the alpha demo shown at E3 back in 1999. It is not known if the FMV scenes shot by Will Binder (or, for that matter, the other game files aside from that demo) still exist, perhaps in the archives of Microsoft, the current legal successor to Sierra.

In addition to FirstOnes, another source on Babylon 5: Into the Fire I can suggest is B5Scrolls, which has interviews of many people involved in working on Babylon 5. The specific people are Jack Nichols (3D artist) and Randy Littlejohn (game designer). Also, MetalJesusRocks has preserved an audio interview with Sierra employees that were laid off in 1999, but maybe you’re already familiar with it.

Jimmy Maher

November 13, 2024 at 1:48 pm

You’ve probably written this up as thoroughly as I could if not more. ;) I do want to write something next year on the late stages of the space-sim genre, and it will be worth mentioning there. But I’m afraid it’s a little too niche to be the subject of a whole feature article. I generally shy away from the “games that weren’t” genre on this site. I have too many worthy games that were too write about! Sorry to disappoint…