By 1993, textual interactive fiction was reaching the end of the unsettled, uncertain half-decade-and-change between the shuttering of Infocom and the rise of a new Internet-centered community of amateur enthusiasts. Efforts by such collectives as Adventions and High Energy Software to sell text adventures via the shareware model had largely proved unfruitful, while, with the World Wide Web still in its infancy, advertisement and distribution were major problems even for someone willing to release her games for free. The ethos of text and parsers seemed about as divorced as anything could possibly be from the predominant ethos in game development more generally, with its focus on multimedia, full-motion video, and ultra-accessible mouse-driven interfaces. Would text adventures soon be no more than obscure relics of a more primitive past? To an increasing number even of the form’s most stalwart fans, an answer in the affirmative was starting to feel like a foregone conclusion. Few text-adventure authors had serious ambitions of matching the technical or literary quality of Infocom during this period, much less of exceeding it; the issue for the medium right now was one of simple survival. In this atmosphere, the arrival of any new text adventure felt like a victory against the implacable forces of technological change, which had conspired to all but strangle this new literary form before it had even had time to get going properly.

Thankfully, history would later mark 1993 as the year when the seeds of an interactive-fiction rebirth were planted, thanks to an Englishman who repurposed not only the Infocom aesthetic but also Infocom’s own technology in unexpected ways. Those seeds would flower richly in 1995, Year Zero of the Interactive Fiction Renaissance. I’ll begin that story soon.

Today, though, I’d like to tell you about some of the more interesting games to emerge from the final days of the interstitial period — games which actually overlap, although no one could realize it at the time, with the dawning of the modern interactive-fiction community. Indeed, the games I describe below manage to presage some of the themes of that community despite being the products of a text-adventuring culture that still spent more time looking backward than looking forward. I’m fond of all of them in one way or another, and I’m willing to describe at least one of them as a sadly overlooked classic.

The hiking trip across Europe has been a wonderful experience for two recent college graduates like yourself and your friend Carolyn. From the mansions of England to the beaches of Greece, you’ve walked in the footsteps of the Crusaders and seen sights that few Americans have ever seen.

Carolyn had wanted to skip the Central European nation of Rylvania. “Why bother?” she’d said. “There’s nothing but farmers there, and creepy old castles - nothing we haven’t seen already. The Rylvanians are still living in the last century.”

That, you’d insisted, was exactly why Rylvania was a must-see. The country was an intact piece of living history, a real treasure in this modern age.

If only you hadn’t insisted! As night fell, as you approached a small farming village in search of a quaint inn to spend the night, the howling began. A scant hundred yards from the village, and it happened...the wolves appeared from the black forest around you and attacked. Big, black wolves that leaped for Carolyn’s throat before you could shout a warning, led by a great gray-black animal that easily stood four feet at the shoulder. Carolyn fell to the rocky path, blood gushing from her neck as the wolves faded back into the trees, unwilling, for some unknown reason, to press their attack.

If she dies, it will be your fault. You curse the darkening sky as you cradle Carolyn’s head, knowing that you have little time to find help. Perhaps in the village up the road to the north.

The Horror of Rylvania marks the last shareware release from Adventions, a partnership between the MIT graduate students Dave Baggett and D.A. Leary which was the most sustained of all efforts to make a real business out of selling interactive fiction during the interstitial period. Doubtless for this reason, the Adventions games are among the most polished of all the text adventures made during this time. They were programmed using the sophisticated TADS development system rather than the more ramshackle AGT, with all the benefits that accrued to such a choice. And, just as importantly, they were thoroughly gone over for bugs as well as spelling and grammar problems, and are free of the gawky authorial asides and fourth-wall-breakings that were once par for the course in amateur interactive fiction.

For all that, though, the Adventions games haven’t aged all that well in my eyes. The bulk of them take place in a fantasy land known as Unnkulia, which is trying so hard to ape Zork‘s Great Underground Empire that it’s almost painful to watch. In addition to being derivative, the Unnkulia games think they’re far more clever and hilarious than they actually are — the very name of the series/world is a fine case in point — while the overly fiddly gameplay can sometimes grate almost as much as the writing.

It thus made for a welcome change when Adventions, after making three and a half Unnkulia games, finally decided to try something else. Written by D.A. Leary, The Horror of Rylvania is more plot-driven than Adventions’s earlier games, a Gothic vampire tale in which you actually become a vampire not many turns in. It’s gone down in certain circles as a minor classic, for reasons that aren’t totally unfounded. Although the game has a few more potential walking-dead scenarios than is perhaps ideal, the puzzles are otherwise well-constructed, the implementation is fairly robust, and, best of all, most of the sophomoric attempts at humor that so marked Adventions’s previous games are blessedly absent.

That said, the end result still strikes me more as a work of craftsmanship than genius. The writing has been gone over for spelling and grammar without addressing some of its more deep-rooted problems, as shown even by the brief introduction above; really, now, have “few Americans ever seen” sights advertised in every bog-standard package tour of Europe? (Something tells me Leary hadn’t traveled much at the time he wrote this game.) The writing here has some of the same problems with tone as another Gothic horror game from 1993 set in an ersatz Romania: Quest for Glory IV. It wants to play the horror straight most of the time, and is sometimes quite effective at it — the scene of your transformation from man to vampire is particularly well-done — but just as often fails to resist the centrifugal pull which comedy has on the adventure-game genre.

Still, Horror of Rylvania is the Adventions game which plays best today, and it isn’t a bad choice for anyone looking for a medium-sized old-school romp with reasonably fair puzzles. Its theme adds to its interest; horror in interactive fiction tends to hew more to either H.P. Lovecraft or zombie movies than the Gothic archetypes which Horror of Rylvania intermittently manages to nail. Another extra dimension of interest is added by the ending, which comes down to a binary choice between curing your friend Carolyn from the curse of vampirism, which entails sacrificing yourself in the process, or curing yourself and letting Carolyn sod off. As we’ll shortly see, the next and last Adventions game perhaps clarifies some of the reasons for such a moral choice’s inclusion at the end of a game whose literary ambitions otherwise don’t seem to extend much beyond being a bit of creepy fun.

You let out a sigh of relief as you finish the last paper. “That’s the lot.”

“Good work, ma’am,” says Regalo, your squire. “I was almost afraid we’d be here until midnight.”

“Don’t worry, Regalo, I wouldn’t do a thing like that, especially on my first healthy day after the flu. In any case, Dora wants me home by eight. The papers look dry, so you can take them to Clara’s office.”

As Regalo carries the papers to the adjoining office, you stand up and stretch your aching muscles. You then look through the window and see a flash of lightning outside. It looks like quite a storm is brewing.

“I’m beginning to think my calendar is set wrong,” you say as Regalo returns. “Dibre’s supposed to be cool, dry, and full of good cheer; so far, we’ve had summer heat, constant rain, and far too many death certificates. Perhaps this storm will blow out the heat.”

“I hope it blows out the plague with it, ma’am. I’ve lost three friends already, and my wife just picked it up yesterday. No one likes it when the coroner’s staff is overworked.”

“It doesn’t help that Clara and Resa are both still sick. If we’re lucky, we’ll have Resa back tomorrow, which I’m sure your feet would appreciate. I presume Ernando and Miranda have already left for the day?”

“Yes ma’am.”

“Now I’m really worried. The only thing worse than being the victim of one of Miranda’s pranks is going a day without one of her pranks -– it usually means you missed something. Perhaps she decided to be discrete [sic] for a change.”

“I didn’t get the impression her sense of humor was taking the day off, but I don’t know what she did. It can wait until tomorrow. Is there anything else you need me to do before I leave?”

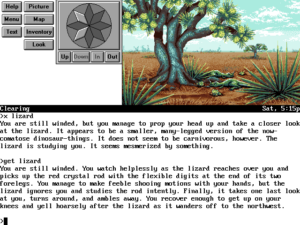

Written by David S. Raley, The Jeweled Arena was the co-winner of what would turn out to be the last of the annual competitions organized by AGT’s steward, David M. Malmberg, before he released the programming language as freeware and stepped away from further involvement with the interactive-fiction community. Set in a fantasy world, but a thankfully non-Zorkian and non-Tolkienesque one, it’s both an impressive piece of world-building and a game of unusual narrative ambition for its time.

In fact, the world of Valdalan seems like it must have existed in the author’s head for a long time before this game was written. The environment around you has the feeling of being rooted in far more lore and history than is explicitly foregrounded in the text, always the mark of first-class world-building. As far as I can tell from the text, Valdalan is roughly 17th-century in terms of its science and technology, but is considerably more enlightened philosophically. Interestingly, magic seems to have no place here, making it almost more of an alternative reality than a conventional fantasy milieu.

The story takes place in the city of Kumeran as it’s in the throes of a plague — a threat which is, like so much else in this game, handled with more subtlety than you might expect. The plot plays out in four chapters, during each of which you play the role of a different character. The first chapter is worthy of becoming a footnote in interactive-fiction history at the very least, in that it casts you as one half of a lesbian couple. In later years, certain strands of interactive fiction — albeit more of the hypertext than the parser-driven type — would become a hotbed of advocacy for non- hetero-normative lifestyles. The Jeweled Arena has perhaps aged better in this respect than many of those works have (or will); it presents its lesbian protagonist in a refreshingly matter-of-fact way, neither turning her into an easy villain or victim, as an earlier game might have done, nor celebrating her as a rainbow-flag-waving heroine, as a later game might have done. She’s just a person; the game takes it as a given that she’s worthy of exactly the same level of respect as any of the rest of us. In 1993, this matter-of-fact attitude toward homosexuality was still fairly unusual. Raley deserves praise for it.

Unfortunately, The Jeweled Arena succeeds better as a place and a story than it does as a game, enough so that one is tempted to ask why Raley elected to present it in the form of a text adventure at all. He struggles to come up with things for you to really do as you wander the city. This tends to be a problem with a lot of interactive fiction where the puzzles aren’t the author’s primary focus; A Mind Forever Voyaging struggles to some extent with the same issue when it sends you wandering through its own virtual city. But The Jeweled Arena, which doesn’t have a mechanic like A Mind Forever Voyaging‘s commandment to observe and record to ease its way, comes off by far the worse of the two. Most of the tasks it sets before you are made difficult not out of authorial intention but due to poor authorial prompting and the inherent limitations of AGT. In other words, first you have to figure out what non-obvious trigger the game is looking for to advance the plot a beat, and then you have to figure out the exact way the parser wants you to say it. This constant necessity to read the author’s mind winds up spoiling what could have been an enjoyable experience, and makes The Jeweled Arena a game that can truly be recommended only to those with an abiding interest in text-adventure history or the portrayal of homosexuality in interactive media. A pity — with more testing and better technology, it could have been a remarkable achievement.

You are standing at the top of an ocean bluff. Wind is whipping through your hair and blowing your voluminous black cape out behind you. You can hear the hiss of the surf crashing far below you. Out towards the horizon, a distant storm sends flickers of lightning across the darkening sky. The last rays of the setting sun reflect red off the windows of the grey stone mansion to the East. As you turn towards the house, you catch a glimpse of a haunting face in one of the windows. That face, you will never forget that face......

> wait

The surf and cliffs fade from sight............

You awake to find yourself in your living room,lying on the couch. Your cat, Klaus, is chewing and pulling on your hair. Static is hissing from the TV, as the screen flickers on a station long off the air. You look at your watch and realize that it is 3 AM.

You must have fallen asleep on the couch right after you got home from work, and settled down to read the newspaper.

I noted earlier that the Adventions games are “free of the gawky authorial asides and fourth-wall-breakings” that mark most early amateur interactive fiction. That statement applies equally to The Jeweled Arena, but not at all to Carol Hovick’s Klaustrophobia. The other winner of the final AGT competition, its personality could hardly be more different from its partner on the podium. This is a big, rambling, jokey game that’s anything but polished. And yet it’s got an unpretentious charm about it, along with puzzles that turn out to be better than they first seem like they’re going to be.

What Klaustrophobia lacks in polish or literary sophistication, it attempts to make up for in sheer sprawl. It’s actually three games in one — so big that, even using the most advanced and least size-constrained version of AGT, Hovick was forced to split it into three parts, gluing them together with some ingenious hacks that are doubtless horrifying in that indelible AGT way to any experienced programmer. The three parts together boast a staggering 560 rooms and 571 objects, making Klaustrophobia easily one of the largest text adventures ever created.

Like the Unnkulia series and so much else from the interstitial period, Klaustrophobia is hugely derivative of the games of the 1980s. The story and puzzles here draw heavily from Infocom’s Bureaucracy, which is at least a more interesting choice than yet another Zork homage. You’ve just won an all-expenses-paid trip to appear on a quiz show, but first you have to get there; this exercise comes to absorb the first third of the game. Then, after you’ve made the rounds of not one but several quiz shows in the second part, part three sends you off to “enjoy” the Mexican vacation you’ve won. As a member of that category of text adventure which the Interactive Fiction Database dubs the “slice of life,” the game has that time-capsule quality I’ve mentioned before as being such a fascinating aspect of amateur interactive fiction. Klaustrophobia is a grab bag of pop-culture ephemera from the United States of 1993: Willard Scott, Dolly Parton, The Price is Right. If you lived through this time and place, you might just find it all unbearably nostalgic. (Why do earlier eras of history almost invariably seem so much happier and simpler?) And if you didn’t… well, there are worse ways to learn about everyday American life in 1993, should you have the desire to do so, than playing through this unforced, agenda-less primary source.

The puzzles are difficult in all the typical old-school ways: full of time limits, requiring ample learning by death. Almost inevitably given the game’s premise, they sometimes fail to fall on the right side of the line between being comically aggravating and just being aggravating. And the game is rough around the edges in all the typical AGT ways: under-tested (a game this large almost has to be) and haphazardly written, and subject to all the usual frustrations of the AGT parser and world model. Yet, despite it all, the author’s design instincts are pretty good; most of the puzzles are clued if you’re paying attention. Many of them involve coming to understand and manipulate some surprisingly complex dynamic sequences taking place around you. The whole experience is helped immensely by the episodic structure which exists even within each of the three parts: you go from your home to the bank to the airport, etc., with each vignette effectively serving as its own little self-contained adventure game. This structure lets Klaustrophobia avoid the combinatorial explosion that can make such earlier text-adventure epics as Acheton and Zork Zero all but insoluble. Here, you can work out a single episode, then move on to the next at your leisure with a nice sense of achievement in your back pocket — as long, of course, as you haven’t left anything vital behind.

Klaustrophobia is a game that I regard with perhaps more affection than I ought to, given its many and manifest flaws. While much of my affection may be down to the fact that it was one of the first games I played when I rediscovered interactive fiction around the turn of the millennium, I like to believe this game has more going for it than nostalgia. It undoubtedly requires a certain kind of player, but, whether taken simply as a text adventure or as an odd sort of sociological study — a frozen-in-amber relic of its time and place — it’s not without its intrinsic appeal. Further, it strikes me as perfect for its historical role as the final major statement made with AGT; something more atypically polished and literary, such as Shades of Gray or even Cosmoserve, just wouldn’t work as well in that context. Klaustrophobia‘s more messy sort of charm, on the other hand, feels like the perfect capstone to this forgotten culture of text adventuring, whose games were more casual but perhaps in some ways more honest because of it.

The Legend Lives!

A pattern of bits shifts inside your computer. New information scrolls up the screen.

It is not good.

As the impact of the discovery settles on your psyche, you recall the preceding events: your recent enrollment at Akmi Yooniversity; your serendipitous discovery of the joys of Classical Literature – a nice change of pace from computer hacking; your compuarchaeological discovery of the long-forgotten treasures that will make your thesis one of the most important this decade. But now that’s all a bit moot, isn’t it?

How ironic: You were stunned at how *real* the primitive Unnkulian stories seemed. Now you know why.

David Baggett’s The Legend Lives! is the only game on this curated list that dates from 1994, the particularly fallow year just before the great flowering of 1995. The very last production of the Adventions partnership, it was originally planned as another shareware title, but was ultimately released for free, a response to the relatively tepid registration rate of Advention’s previous games. Having conceived it as nothing less than a Major Statement meant to prod the artistic growth of a nascent literary medium, Baggett stated that he wished absolutely everyone to have a chance to play his latest game.

Ironically, the slightly uncomfortable amalgamation that is The Legend Lives! feels every bit as of-its-time today as any of the less artistically ambitious text adventures I’ve already discussed in this article. Set in the far future of Adventions’s Unnkulia universe, it reads like a checklist of what “literary” interactive fiction circa 1994 might be imagined to require.

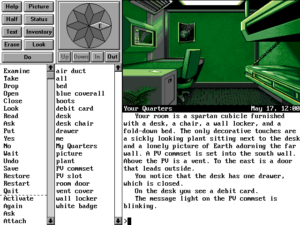

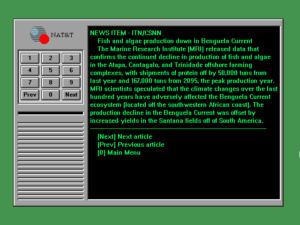

There must, first and foremost, be lots and lots of words for something to be literary, right? Baggett has this covered… oh, boy, does he ever. The first room description, for the humble dorm room of the university student you play, consists of six substantial paragraphs — two or three screenfuls of text on the typical 80-column monitor displays of the day. As you continue to play, every object mentioned anywhere, no matter how trivial, continues to be described to within an inch of its life. While Baggett’s dedication is admirable, these endless heaps of verbiage do more to confuse than edify, especially in light of the fact that this game is, despite its literary aspirations, far from puzzleless. There’s a deft art to directing the player’s attention to the things that really matter in a text adventure — an art which this game comprehensively fails to exhibit. And then there are the massive non-interactive text dumps, sometimes numbering in the thousands of words, which are constantly interrupting proceedings. Sean Molley, reviewing the game in the first gush of enthusiasm which accompanied its release, wrote that “I certainly don’t mind reading 10 screens of text if it helps to advance the story and give me something to think about.” I suspect that most modern players wouldn’t entirely agree. The Legend Lives! is exhausting enough in its sheer verbosity to make you long for the odd minimalist poetry of Scott Adams. “Ok, too dry. Fish die” starts looking pretty good after spending some time with this game.

And yet, clumsy and overwrought though the execution often is, there is a real message here — one I would even go so far as to describe as thought-provoking. The Legend Lives! proves to be an old-school cyberpunk tale — another thing dating it indelibly to 1994 — about a computer virus that has infected Unnkulia’s version of the Internet and threatens to take over the entirety of civilization. The hero that emerges and finally sacrifices himself to eliminate the scourge is known mostly by his initials: “JC.” He’s allegedly an artificial intelligence, but he’s really, it would seem, an immaculate creation, a divinity living in the net. An ordinary artificial intelligence, says one character, “is smart with no motivation, no goals; no creativity, ya see. JC, he’s like us.” What we have here, folks, is an allegory. I trust that I need not belabor the specific parallels with another famous figure who shares the same initials.

But I don’t wish to trivialize the message here too much. It’s notable that this argument for a non-reductionist view of human intelligence — for a divine spark to the human mind that can’t be simulated in silicon — was made by a graduate student in MIT’s artificial-intelligence lab, working in the very house built by Marvin Minsky and his society of mind. Whatever one’s feelings about the Christian overtones to Baggett’s message, his impassioned plea that we continue to allow a place for the ineffable has only become more relevant in our current age of algorithmization and quantization.

Like all of the Adventions games, this one has been virtually forgotten today, despite being widely heralded upon its release as the most significant work of literary interactive fiction to come along since A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity. That’s a shame. Yes, writers of later text adventures would learn to combine interactivity with literary texture in more subtle and effective ways, but The Legend Lives! is nevertheless a significant way station in the slow evolution of post-Infocom interactive fiction, away from merely reflecting the glory of a storied commercial past and toward becoming a living, evolving artistic movement in its own right.

Perdition’s Flames

*** You have died. ***

All is dark and quiet. There is no sensation, no time. Your mind floats peacefully in a void. You perceive nothing, you feel nothing, you think nothing. Sleep without dreams.

All is hazy and gray. Sensation is vague and indistinct. Your mind is sluggish, sleepy. You see gray shapes in a gray fog; you hear distant, muffled sounds. You think, but your thoughts are fleeting, disconnected, momentary flashes of light in a dark night. Time is still frames separated by eons of nothing, brief awakenings in a long sleep.

All is clear and sharp. Sensation crystalizes from a fog. You see, you hear, you feel. Your mind awakens; you become aware of a place, and a time.

You are on a boat.

Last but far from least, we come to the real jewel of this collection, a game which I can heartily recommend to everyone who enjoys text adventures. Perdition’s Flames was the third game written by Mike Roberts, the creator of the TADS programming language. While not enormous in the way of Klaustrophobia, it’s more than substantial enough in its own right, offering quite a few hours of puzzling satisfaction.

The novel premise casts you as a soul newly arrived in Hell. (Yes, just as you might expect, there are exactly 666 points to score.) Luckily for you, however, this is a corporate, postmodern version of the Bad Place. “Ever since the deregulation of the afterlife industry,” says your greeter when you climb off the boat, “we’ve had to compete with Heaven for eternal souls — because you’re free to switch to Heaven at any time. So, we’ve been modernizing! There really isn’t much eternal torment these days, for example. And, thanks to the Environmental Clean-up Superfund, we have the brimstone problem mostly under control at this point.”

As the game continues, there’s a lot more light satire along those lines, consistently amusing if not side-splittingly funny. Finishing the whole thing will require solving lots and lots of puzzles, which are varied, fair, and uniformly enjoyable. In fact, I number at least one of them among the best puzzles I’ve ever seen. (For those who have already played the game: that would be the one where you’re a ghost being pursued by a group of paranormal researchers.)

Although Perdition’s Flames is an old-school puzzlefest in terms of categorization, it’s well-nigh breathtakingly progressive in terms of its design sensibility. For this happens to be a text adventure — the first text adventure ever, to my knowledge — which makes it literally impossible for you to kill yourself (after all, you are already dead) or lock yourself out of victory. It is, in other words, the Secret of Monkey Island of interactive fiction, an extended proof that adventure games without deaths or dead ends can nevertheless be intriguing, challenging, and immensely enjoyable. Roberts says it right there in black and white:

Note that in Perdition’s Flames, in contrast to many other adventure games, your character never gets killed, and equally importantly, you’ll never find yourself in a position where it’s impossible to finish the game. You have already seen the only “*** You have died ***” message in Perdition’s Flames. As a result, you don’t have to worry as much about saving game positions as you may be accustomed to.

I can’t emphasize enough what an astonishing statement that is to find in a text adventure from 1993. Perdition’s Flames and its author deserve to be celebrated for making it every bit as much as we celebrate Monkey Island and Ron Gilbert.

Yet even in its day Perdition’s Flames was oddly overlooked in proportion to its size, polish, and puzzly invention alone, much less the major leap it represents toward an era of fairer, saner text adventures. And this even as the merciful spirit behind the humble statement above, found buried near the end of the in-game instructions, was destined to have much more impact on the quality of the average player’s life than all of the literary pretensions which The Legend Lives! so gleefully trumpets.

Roberts’s game was overshadowed most of all by what would go down in history as the text adventure of 1993: Graham Nelson’s Curses!. Said game is erudite, intricate, witty, and sometimes beautifully written — and runs on Infocom’s old Z-Machine, which constituted no small part of its appeal in 1993. But it’s also positively riddled with the types of sudden deaths and dead ends which Perdition’s Flames explicitly eschews. You can probably guess which of the pair holds up better for most players today.

So, as we prepare to dive into the story of how Curses! came to be, and of how it turned into the seismic event which revitalized the near-moribund medium of interactive fiction and set it on the path it still travels today, do spare a thought for Perdition’s Flames as well. While Curses! was the first mover that kicked the modern interactive-fiction community into gear, Perdition’s Flames, one might argue, is simply the first work of modern interactive fiction, full stop. All of its contemporaries, Curses! included, seem regressive next to its great stroke of genius. Go forth and play it, and rejoice. An Interactive Fiction Renaissance is in the offing.

(All of the games reviewed in this article are freely available via the individual links provided above and playable on Windows, Macintosh, and Linux using the Gargoyle interpreter among other options.)