Sometimes success smacks you right in the face. More often, it sneaks up on you from behind.

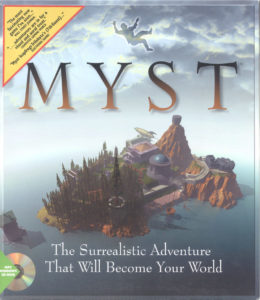

In September of 1993, the brothers Rand and Robyn Miller and the few other employees of Cyan, Inc., were prototypical starving artists, living on “rice and beans and government cheese.” That month they saw Brøderbund publish their esoteric Apple Macintosh puzzle game Myst, which they and everyone else regarded as a niche product for a niche platform. There would go another year before it became abundantly clear that Myst, now available in a version for Microsoft Windows as well as for the Mac, was a genuine mass-market hit. It would turn into the gift that kept on giving, a game with more legs than your average millipede. It wouldn’t enjoy its best single month until December of 1996, when it would set a record for the most copies one game had ever sold in one month.

All of this — not just the sales figures themselves but the dozens of awards, the write-ups in glossy magazines like Rolling Stone and Newsweek, the fawningly overwritten profiles in Wired, the comparisons with Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park and Michael Jackson’s Thriller — happened just gradually enough that it seemed almost natural. Almost natural. “It took a while for it to hit me that millions of people were buying this game,” says Robyn Miller. “The most I could really wrap my head around would be to go to a huge concert and see all of the people there and think, ‘Okay, this is not even a portion of the people who are playing Myst.'”

The Miller brothers could have retired and lived very comfortably for the rest of their lives on the fortune they earned from Myst. They didn’t choose this path. “We took salaries that were fairly modest and just put the company’s money back into [a] new project,” says Rand.

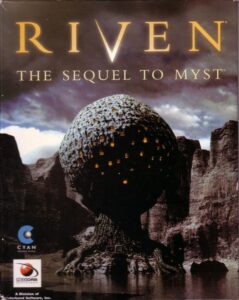

Brøderbund was more than eager for a sequel to Myst, something that many far smaller hits than it got as a matter of course within a year. But the Miller brothers refused to be hurried, and did not need to be, a rare luxury indeed in their industry. Although they enjoyed a very good relationship with Brøderbund, whose marketing acumen had been essential to getting the Myst ball rolling, they did not wish to be beholden to their publisher in any way. Rather than accepting the traditional publisher advance, they decided that they would fund the sequel entirely on their own out of the royalties of the first game. This meant that, as Myst blew up bigger and bigger, their ambitions for the game they intended to call Riven were inflated in tandem. They refused to give Brøderbund a firm release date; it will be done when it’s done, they said. They took to talking about Myst as their Hobbit, Riven as their Lord of the Rings. It had taken J.R.R. Tolkien seventeen years to bridge the gap between his children’s adventure story and the most important fantasy epic in modern literary history. Surely Brøderbund could accept having to wait just a few years for Riven, especially with the sales figures Myst was still putting up.

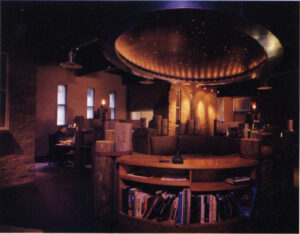

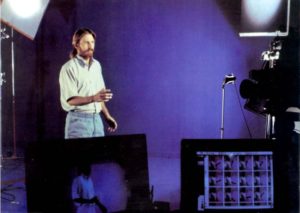

Cyan’s digs reflected their rising status. They hadn’t even had a proper office when they were making Myst; everybody worked out of their separate homes in and around Spokane, Washington, sharing their output with one another using the “car net”: put it on a disk, get into your car, and drive it over to the other person. In the immediate aftermath of Myst’s release and promising early sales, they all piled into a drafty, unheated garage owned by their sound specialist Chris Brandkamp. Then, as the sales numbers continued to tick upward, they moved into an anonymous-looking former Comfort World Mattress storefront. Finally, in January of 1995, they broke ground on a grandiosely named “Cyan World Headquarters,” whose real-world architecture was to be modeled on the virtual architecture of Myst and Riven. While they were waiting for that building to be completed — the construction would take eighteen months — they junked the consumer-grade Macs which had slowly and laboriously done all of the 3D modeling necessary to create Myst’s environments in favor of Silicon Graphics workstations that cost $40,000 a pop.

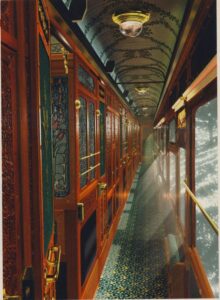

The machines that made Riven. Its imagery was rendered using $1 million worth of Silicon Graphics hardware: a dozen or so workstations connected to these four high-end servers that did the grunt work of the ray-tracing. It was a far cry from Myst, which had been made with ordinary consumer-grade Macs running off-the-shelf software.

There were attempts to drum up controversies in the press, especially after Riven missed a tentative Christmas 1996 target date which Brøderbund had (prematurely) announced, a delay that caused the publisher’s stock price to drop by 25 percent. The journalists who always seemed to be hovering around the perimeter of Cyan’s offices claimed to sniff trouble in the air, an aroma of overstretched budgets and creative tensions. But, although there were certainly arguments — what project of this magnitude doesn’t cause arguments? — there was in truth no juicy decadence or discord going on at Cyan. The Miller brothers, sons of a preacher and still devout Christians, never lost their Heartland groundedness. They never let their fluke success go to their heads in the way of, say, the minds behind Trilobyte of The 7th Guest fame, were never even seriously tempted to move their operation to some more glamorous city than Spokane. For them, it was all about the work. And luckily for them, plenty of people were more than willing to move to Spokane for a chance to work at The House That Myst Built, which by the end of 1995 had replaced Trilobyte as the most feted single games studio in the mainstream American press, the necessary contrast to all those other unscrupulous operators who were filling their games and the minds of the nation’s youth with indiscriminate sex and violence.

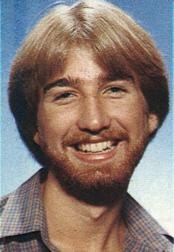

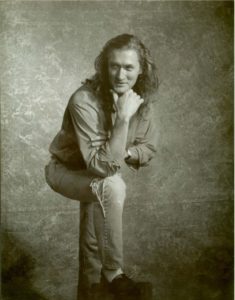

The most important of all the people who were suddenly willing to come to Spokane would prove to be Richard Vander Wende, a former Disney production designer — his fingerprints were all over the recent film Aladdin — who first bumped into the Miller brothers at a Digital World Expo in Los Angeles. Wende’s conceptual contribution to Riven would be as massive as that of either of the Miller brothers, such that he would be given a richly deserved co-equal billing with them at the very top of the credits listing.

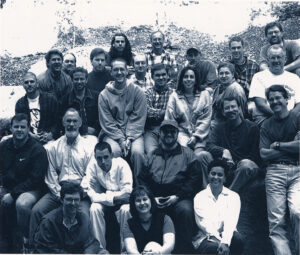

Needless to say, though, there were many others who contributed as well. By the time Cyan moved into their new world headquarters in the summer of 1996, more than twenty people were actively working on Riven every day. The sequel would wind up costing ten times to fifteen times as much to make as its predecessor, filling five CDs to Myst’s lone silver platter.

Given the Millers’ artistic temperament and given the rare privilege they enjoyed of being able to make exactly the game they wished to make, one might be tempted to assume that Riven was to be some radical departure from what had come before. In reality, though, this was not the case at all. Riven was to be Myst, only more so; call it Myst perfected. Once again you would be left to wander around inside a beautiful pre-rendered 3D environment, which you would view from a first-person perspective. And once again you would be expected to solve intricate puzzles there — or not, as you chose.

Cyan had long since realized that players of Myst broke down into two broad categories. There were those they called the gamers, who engaged seriously with it as a series of logical challenges to be overcome through research, experimentation, and deduction. And then there was the other group of players — a far, far larger one, if we’re being honest — whom Cyan called the tourists, who just wanted to poke around a little inside the virtual world and take in some of the sights and sounds. These were folks like the residents of a retirement home who wrote to Cyan to say that they had been playing and enjoying Myst for two years and two months, and wanted to hear if the rumors that there were locations to explore beyond the first island — an island which constitutes about 20 percent of the full game — were in fact true.

Riven was meant to cater to both groups, by giving the gamers a much deeper, richer, more complex tapestry of puzzles to unravel, whilst simultaneously being kept as deliberately “open” as possible in terms of its geography, so that you could see most of its locations without ever having to solve a single conundrum. “The two complaints about Myst,” said Rand Miller, “were that it was too hard and too easy. We’re trying to make Riven better for both kinds of players.” Whereas Myst allowed you to visit four separate “ages” — basically, alternative dimensions — after solving those early puzzles which had so stymied the retirees, Riven was to take place all in the same dimension, on a single archipelago of five islands. You would be able to travel between the islands right from the start, using vehicles whose operation should be quite straightforward even for the most puzzle-averse players. If all you wanted to do was wander around the world of Riven, it would give you a lot more spaces in which to do so than Myst.

Of course, while the world of Riven was slowly coming together, the real world wasn’t sitting still. Myst had been followed by an inevitable flood of “Myst clones” from other publishers and studios, which, in lieu of a proper sequel from Cyan, did their best to pick up the slack by offering up their own deserted, 3D-rendered environments to explore. None of them was more than modestly successful; Activision’s Zork Nemesis, which may have done the best of them all, sold perhaps 150,000 copies, barely one-fiftieth of the final numbers that Myst put up when all was said and done. Meanwhile the genre of adventure games in general had peaked in the immediate aftermath of Myst and would be well into an increasingly precipitous decline by the time Riven shipped in October of 1997. The Last Express, the only other adventure that Brøderbund published that year, stiffed badly in the spring, despite sporting prominently on its box the name of Jordan Mechner, one of the few videogame auteurs with a reputation to rival that of the Miller brothers.

Yet Cyan’s own games still seemed weirdly proof against the marketplace pressures that were driving so many other game makers in the direction of real-time strategy and first-person shooters. In June of 1997, the nearly four-year-old Myst was propelled back to the top of the sales charts by the excitement over the approaching debut of Riven. And when it did appear, Riven didn’t disappoint the bean counters. It and Myst tag-teamed one another in the top two chart positions right through the Christmas buying season. Myst would return to number one a few more times in the course of 1998, while an entire industry continued to scratch its collective head, wondering why this particular game — a game that was now approaching its fifth birthday, making it roughly as aged as the plays of Shakespeare as the industry reckoned time — should continue to sell in such numbers. Even today, it’s hard to say precisely why Myst just kept selling and selling, defying all the usual gravities of its market. It seems that non-violent, non-hardcore gaming simply needed a standard bearer, and so it found one for itself.

Riven wasn’t quite as successful as Myst, but this doesn’t mean it didn’t do very well indeed by all of the standard metrics. Its biggest failing in comparison to its older sibling was ironically its very cutting-edge nature; whereas just about any computer that was capable of running other everyday software could run Myst by 1997, you needed a fairly recent, powerful machine to run Riven. Despite this, and despite the usual skepticism from the hardcore-gaming press — “With its familiar, lever-yanking gameplay, Riven emerges as the ultimate Myst clone,” scoffed Computer Gaming World magazine — Riven’s sales surpassed 1 million units in its first year, numbers of which any other adventure game could scarcely have dreamed.[1]An article in the May 17 2001 edition of the Los Angeles Times claimed that Riven had sold 4.5 million copies by that point, three and a half years after its release. This number has since been repeated in numerous places, including Wikipedia. I’ll eat my hat if it’s correct; this game would have left a much wider vapor trail behind it if it was. Read in context in the original article, the figure actually comes across as a typo.

Riven was a huge hit by any conventional standard, but it didn’t have the legs of Myst. Already for long stretches during 1998, it was once again being comfortably outsold by Myst. Lifetime retail sales of around 1.5 million strike me as the most likely figure — still more than enough to place Riven in the upper echelon of late 1990s computer games.

Fans and boosters of the genre naturally wanted to see a broader trend in Riven’s sales, a proof that adventures in general could still bring home the bacon with the best of them. The hard truth that the games of Cyan were always uniquely uncoupled from what was going on around them was never harder to accept than in this case. In the end, though, Riven would have no impact whatsoever on the overall trajectory of the adventure genre.

Because Riven is a sequel in such a pure sense — a game that aims to do exactly what its predecessor did, only bigger and better — your reaction to it is doomed to be dictated to a large extent by your reaction to said predecessor. It’s almost impossible for me to imagine anyone liking or loving Riven who didn’t at least like Myst.

The defining quality of both games is their thoroughgoing sense of restraint. When Myst first started to attract sales and attention, naysayers saw its minimalism through the lens of technical affordance, or rather the Miller brothers’ lack thereof: having only off-the-shelf middleware like HyperCard to work with, lacking the skill set that might have let them create better tools of their own, they just had to do the best they could with what they had. In this reading, Myst‘s static world, its almost nonexistent user interface, its lack of even such niceties as a player inventory, stemmed not so much from aesthetic intent as from the fact that it had been created with a hypertext editor that had never been meant for making games. The alternative reading is that the Miller brothers were among the few game developers who knew the value of restraint from the start, that they were by nature and inclination minimalists in an industry inclined to maximalism in all things, and this quality was their greatest strength rather than a weakness. The truth probably lies somewhere between the two extremes, as it usually does. Regardless, there’s no denying that the brothers leaned hard into the same spirit of minimalism that had defined Myst when the time came to make Riven, even though they were now no longer technologically constrained into doing so. One camp reads this as a colossal failure of vision; the other reads it as merely staying true to the unique vision that had gotten them this far.

While I don’t want to plant myself too firmly in either corner, I must say that I am surprised by some of the things that Cyan didn’t do with twice the time and ten or fifteen times the budget. The fact that Riven still relies on static, pre-rendered scenery and node-based movement isn’t the source of my surprise; that compromise was necessary in order to achieve the visual fidelity that Cyan demanded. I’m rather surprised by how little Cyan innovated even within that basic framework. Well before Riven appeared, the makers of other Myst successors had begun to experiment with ways of creating a slightly more fluid, natural-feeling experience. Zork Nemesis, for example, stores each of its nodes as a 360-degree panorama instead of a set of fixed views, letting you smoothly turn in place through a complete circle. Riven, by contrast, confines its innovations in this area to displaying a little transition animation as you rotate between its rigidly fixed views. As a result, switching from view to view does become a little less jarring than it is in Myst, but the approach is far from even the Myst-clone state of the art.

Cyan was likewise disinterested in pursuing other solutions that would have been even easier to implement than panning rotation, but that could have made their game less awkward to play. The extent of your rotation when you click on the left or right side of the screen remains inconsistent, just as it was in Myst; sometimes it’s 90 degrees, sometimes it’s less or more. This can make simple navigation much more confusing than it needs to be, introducing a layer of fake difficulty — i.e., difficulties that you would not have if you were really in this world — which seems at odd with Cyan’s stated determination to create as immersive an experience as possible. Even a compass with which to tell which way you’re facing at any given time would have helped enormously, but no such concessions to player convenience are to hand.

Again, these are solutions that the other makers of Myst clones — not a group overly celebrated for its spirit of innovation — had long since deployed. Cyan was always a strangely self-contained entity, showing little awareness of what others were doing around them, making a virtue of their complete ignorance of the competition. In cases like these, it was perhaps not so much a virtue as a failure of simple due diligence. Building upon the work of others is the way that gaming as a whole progresses.

When it comes to storytelling as well, Riven’s differences from Myst are more a matter of execution than kind. As in Myst, there is very little story at all here, if by that we mean a foreground plot driving things along. A brief bit of exposition at the beginning picks up right where Myst ended, providing an excuse for dumping you into another open-ended environment. Whereas Myst took place entirely in deserted ages, here you’re ostensibly surrounded by the Rivenese, the vaguely Native-American-like inhabitants of the archipelago. Rather conveniently for Cyan, however, the Rivenese are terrified of strangers, and scurry away into hiding whenever you enter a scene. The few named characters you meet, including the principal villain, are likewise forever just leaving when you come upon them, or showing up, giving speeches, and then going away again before you can interact with them. By 1997, this sort of thing was feeling more tired than clever.

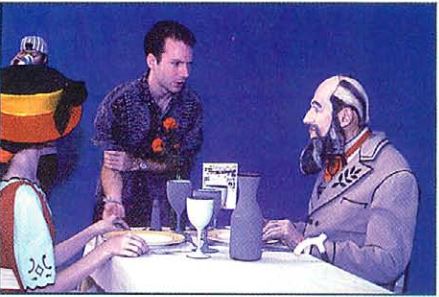

Rand Miller, returning in the role of the patriarch Atrus from Myst, gives you your marching orders and sends you on your way in the introductory movie. Riven makes more extensive use of such scenes involving real actors than Myst, but it’s done well, and never overdone. The end result is about as un-cheesy as these techniques can possibly look to modern eyes.

The real story, in both Myst and Riven, is the backstory that caused these spaces to become the places they are, a backstory which you uncover as you explore them. And in this area, I’m happy to say, Riven actually does outdo its predecessor. Almost everything there is to find out about how the ages of Myst became as they are is conveyed in one astonishingly clumsy infodump, a set of books which you find in a library on that first island after solving the first couple of puzzles. These stop your progress dead for an hour or so as you read through them, after which you’re back to exploring, never to be troubled by much of any exposition again.

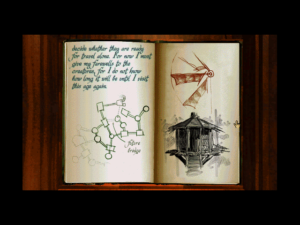

By the time of Riven, however, the Miller brothers had learned about the existence of something called dramatic pacing. Here, too, most of the real story comes in the form of books and journals, but these are scattered around the islands, providing an enticement to solve puzzles in order to acquire and read them. The Myst “universe” grew considerably in depth and coherency between Myst and Riven, thanks to a trilogy of novels written by the British science-fiction author David Wingrove in close collaboration with the Miller brothers during that interim. In Riven, then, you get some of the same sense that you get in The Lord of the Rings, that you are only scraping the surface of a world that goes much deeper than its foreground sights and sounds. “The Lord of the Rings is so satisfying because of the details,” said Rand Miller at the time. “You get the feeling that the world you’re reading about is real. Different but real. That’s how we go about designing.” Like Tolkien, the Miller brothers went so far as to make up the beginnings at least of a coherent language for their land’s inhabitants. This sense of established lore, combined with the improved pacing and better writing, makes Riven’s backstory more compelling than that of Myst, makes uncovering more of it feel like a worthwhile goal in itself. Instead of providing a mere excuse for the gameplay, as in Myst, Riven’s backstory comes to fuel its gameplay to a large extent.

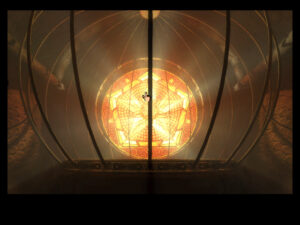

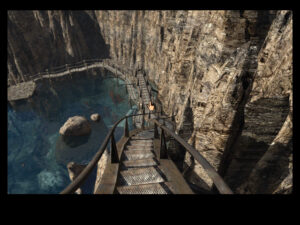

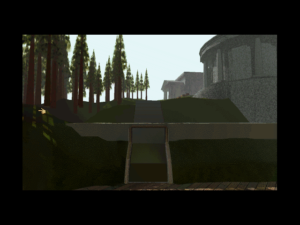

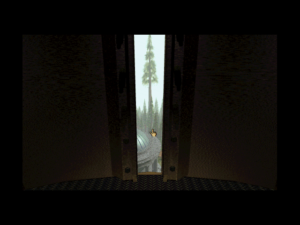

And this starts to take us into the territory of the first of the two things that Riven does really, really well, does so well in fact that you might just be willing to discount all of the failings I’ve been belaboring up to this point. The archipelago is a truly intriguing, even awe-inspiring place to explore, thanks not just to the cutting-edge 3D-rendering technology that was used to bring it to life, but — and even more so — the thought that went into the place.

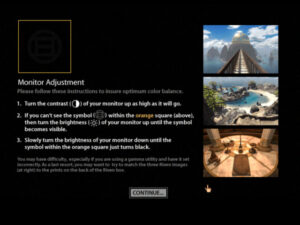

Riven makes its priorities clear from the beginning, when it asks you to set up your screen and your speakers to provide the immersive audiovisual experience it intends for you to have.

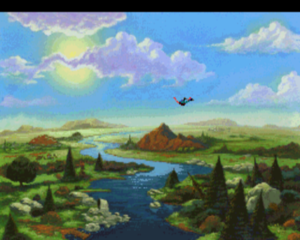

The adjective “surreal” seems unavoidable when discussing Myst, so much so that Brøderbund built it right into their advertising tagline. (“The Surrealistic Adventure That Will Become Your World.”) Looking back on it now, though, I realize that the surrealism of Myst was as much a product of process as intention. The 3D-modeling software that was used to create the scenery of Myst couldn’t render genuinely realistic scenes; everything it churned out was too geometrical, too stiff, too uniform in color to look in any sense real. The result was surrealism, that forlorn, otherworldly, even vaguely disturbing stripe of beauty that became the hallmark of Myst and its many imitators.

But I would not call Riven surreal. The improved technology that enabled it, on both the rendering side — meaning all those Silicon Graphics servers and workstations, with their complex ray-tracing algorithms — and the consumer-facing side — meaning the latest home computers, with their capability of displaying millions of nuanced shades of color onscreen at once — led to a more believable world. The key to it all is in the textures, the patterns that are overlaid onto the frame of a 3D model in lieu of blocks of solid color to make it look like a real object made out of wood, metal, or dirt. Cyan traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to capture thousands of textures. The same visual qualities that led to that state being dubbed the “Land of Enchantment” and drew artists like Georgia O’Keeffe to its high deserts suffuses the game, from the pueblo walls of the Rivenese homes to the pebbly cliff-side paths, from an old iron tower rusting in the sun to the ragged vegetation huddling around it. You can almost feel the sun on your back and the sweat on your skin.

My wife and I are inveterate hikers these days, planning most of our holidays around where we can get out and walk. Riven made me want to climb through the screen and roam its landscapes for myself. Myst has its charms, but they are nothing like this. When I compare the two games, I think about what a revelation the battered, weathered world of Tatooine was when Star Wars hit cinemas in 1977, how at odds it was with the antiseptic sleekness of the science-fiction films that preceded it. Riven is almost as much of a revelation when set beside Myst and its many clones.

The visuals both feed and are fed by the backstory and the world-building. The islands are replete with little details that have nothing to do with solving the game, that exist simply as natural, necessary parts of this place you’re exploring. In a perceptive video essay, YouTube creator VZedshows notes how “the lived-in world of Riven lets us look at a house and say, ‘Okay, that’s a house.’ And that’s it. A totally different thought than seeing a log cabin on Myst Island and saying, ‘Okay, that’s a house. But what is it for?’ The puzzles in Riven melt into the world around them.”

Which brings us neatly to the other thing that Riven does remarkably well, the one aimed at the gamers rather than the tourists. Quite simply, Riven is one of the most elegantly sophisticated puzzle games ever created. This facet of it is not for everyone. (I’m not even sure it’s for me, about which more in a moment.) But it does what it sets out to do uncompromisingly well. Riven is a puzzle game that doesn’t feel like a puzzle game. It rather feels like you really have been dropped onto this archipelago, with its foreign civilization and all of its foreign artifacts, and then left to your own devices to make sense of it all.

Many of Riven’s puzzles are as much anthropological as mechanical. For example, you have to learn to translate the different symbols of a foreign number system.

This is undoubtedly more realistic than the ages of Myst, whose puzzles stand out from their environs so plainly that they might as well be circled with a bright red Sharpie. But does it lead to a better game? As usual, the answer is in the eye of the beholder. Ironically, almost everything that can be said about Riven’s puzzles can be cast as either a positive or a negative. If you’re looking for an adventure game that’s nails-hard and yet scrupulously fair — a combination that’s rarer than it ought to be — Riven will not disappoint you. If not, however, it will put you right off just as soon as you grow bored with idle wandering and begin to ask yourself what the game expects you to actually be doing. Myst was widely perceived in the 1990s as being more difficult than it really was; Riven, by contrast, well and truly earns its reputation.

Each of Myst’s ages is a little game unto itself when it comes to its puzzles; you never need to use tools or information from one age to overcome a problem in another one. For better or for worse, Riven is not like that — not at all. Puzzles and clues are scattered willy-nilly all over the five islands; you might be expected to connect a symbol you’re looking at now to a gadget you last poked at hours and hours ago. Careful, copious note-taking is the only practical way to proceed. I daresay you might end up spending more time poring over your real-world journal, looking for ways to combine and thereby to make sense of the data therein, than you do looking at the monitor screen. Because most of the geography is open to you from the very beginning — this is arguably Riven’s one real concession to the needs of the marketplace, being the one that allows it to cater to the tourists as well as the gamers — there isn’t the gated progress you get in so many other puzzly adventure games, with new areas and new problems being introduced gradually as you solve the earlier ones. No, Riven throws it all at you from the start, in one big lump. You just have to keep plugging away at it when even your apparently successful deductions don’t seem to be yielding much in the way of concrete rewards, trusting that it will all come together in one big whoosh at the end.

All of which is to say that Riven is a slow game, the polar opposite of the instant gratification that defines the videogame medium in the eyes of so many. There are few shortcuts for moving through its sprawling, fragmented geography — something you’ll need to do a lot of, thanks to its refusal to contain its puzzles within smaller areas as Myst does. Just double-checking some observation you think you made earlier or confirming that some effect took place as expected represents a significant investment in time. Back in the day, when everyone was playing directly from CD, Riven was even slower than it is today, requiring you to swap discs every time you traveled to a different island.[2]Some months after its original release, Riven became one of the first games ever to be made available on DVD-ROM. No game benefited more from the switch in storage technology; not only were DVD drives faster than CD drives, but a single DVD disc was capacious enough to contain the whole of Riven. In his vintage 1997 review, Andrew Plotkin — a fellow who is without a doubt much, much smarter than I am, at least when it comes to stuff like this — said that he was able to solve Riven in about twenty hours, using just one hint. It will probably take more mortal intelligences some multiple of one or both of those figures.

Your reaction to Riven when approached in “gamer” mode will depend on whether you think this kind of intensive intellectual challenge is fun or not, as well as whether you have the excess intellectual and temporal bandwidth in your current life to go all-in on such a major undertaking. I must sheepishly confess that my answer to the first question is more prevaricating than definitive, while my answer to the second one is a pretty solid no. In the abstract, I do understand the appeal of what Riven is offering, understand how awesome it must feel to put all of these disparate pieces together without help. Nevertheless, when I approached the game for this article, I couldn’t quite find the motivation to persevere down that road. Riven wants you to work a little harder for your fun than the current version of myself is willing to do. I don’t futz around with my notebook too long before I start looking out the window and thinking about how nice it would be to take a walk in real nature. I take enough notes doing research for the articles I write; I’m not sure I want to do so much research inside a game.

Prompted partially by my experience with Riven, I’ve been musing a fair amount lately about the way we receive games, and especially how the commentary you read on this site and others similar to it can be out of step with the way the games in question existed for their players in their heyday. I’m subject to the tyranny of my editorial calendar, to the need to just finish things, one way or another, and move on. Riven is not well-suited to such a mindset. In my travels around the Internet, I’ve noticed that those who remember the game most fondly often took months or years to finish it, or never finished it at all. It existed for them as a tempting curiosity, to be picked up from time to time and poked at, just to see if a little more progress was possible here or there, or whether the brainstorm that came to them unbidden while driving home from work that day might bear some sort of fruit. It’s an open question whether even folks who don’t have an editorial schedule to keep can recapture that mindset here and now, in the third decade (!) of the 21st century, when more entertainment of every conceivable type than any of us could possibly consume in a lifetime is constantly luring us away from any such hard nut as Riven. As of this writing, Cyan is preparing a remake of Riven. It will be interesting to see what concessions, if any, they chose to make to our new reality.

Even in the late 1990s, there was the palpable sense that Riven represented the end of an era, that even Cyan would not be able to catch lightning in a bottle a third time with yet another cerebral, contemplative, zeitgeist-stamping single-player puzzle game. Both Richard Vander Wende and Robyn Miller quit the company as soon as the obligatory rounds of promotional interviews had been completed, leaving the Myst franchise’s future solely in the hands of Rand Miller. Robyn’s stated reason for departing brings to the fore some of the frustrations I have with Cyan’s work. He said that he was most interested in telling stories, and had concluded that computer games just weren’t any good at that: “I felt like, you know what? It’s not working. This whole story thing is not happening, and one of the reasons it’s not happening is because of the medium. It’s not what this medium is good at.” So, he said, he wanted to work in film instead.

The obvious response is that Cyan had never actually tried to tell an engaging foreground story, had rather been content to leave you always picking up the breadcrumbs of backstory. Cyan’s stubborn conservatism in terms of form and their slightly snooty insistence on living in their own hermetically sealed bubble, blissfully unaware of the innovations going on around them in their industry in both storytelling and other aspects of game making, strike me as this unquestionably talented group’s least attractive qualities by far. When asked once what his favorite games were, Richard Vander Wende said he didn’t have any: “Robyn and I are not really interested in games of any kind. We’re more interested in building worlds. To us, Myst and Riven are not ‘games’ at all.” Such scare-quoted condescension does no one any favors.

Then again, that’s only one way of looking at it. Another way is to recognize that Riven is exactly the game — okay, if you like, the world — that its creators wanted to make. It’s worth acknowledging, even celebrating, as the brave artistic statement it is. Love it or hate it, Riven knows what it wants to be, and succeeds in being exactly that — no more, no less. Rather than The Lord of the Rings, call it the Ulysses of gaming: a daunting creation by any standard, but one that can be very rewarding to those willing and able to meet it where it lives. That a game like this outsold dozens of its more visceral, immediate rivals on the store shelves of the late 1990s is surely one of the wonders of the age.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books The Secret History of Mac Gaming (Expanded Edition) by Richard Moss, From Myst to Riven: The Creations & Inspirations by Richard Kadrey, and Riven: The Sequel to Myst: The Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba; Computer Gaming World of January 1998; Retro Gamer 208; Wired of September 1997; Game Developer of March 1998. Plus the “making of” documentary that was included with the DVD version of Riven.

Online sources include GameSpot’s old preview of Riven, Salon’s profile of the Miller brothers on the occasion of Robyn’s departure from Cyan, VZedshows’s video essay on Myst and Riven, and Andrew Plotkin’s old review of Riven.

The original version of Riven is currently available as a digital purchase on GOG.com. As noted in the article above, a remake is in the works at Cyan.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | An article in the May 17 2001 edition of the Los Angeles Times claimed that Riven had sold 4.5 million copies by that point, three and a half years after its release. This number has since been repeated in numerous places, including Wikipedia. I’ll eat my hat if it’s correct; this game would have left a much wider vapor trail behind it if it was. Read in context in the original article, the figure actually comes across as a typo.

Riven was a huge hit by any conventional standard, but it didn’t have the legs of Myst. Already for long stretches during 1998, it was once again being comfortably outsold by Myst. Lifetime retail sales of around 1.5 million strike me as the most likely figure — still more than enough to place Riven in the upper echelon of late 1990s computer games. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Some months after its original release, Riven became one of the first games ever to be made available on DVD-ROM. No game benefited more from the switch in storage technology; not only were DVD drives faster than CD drives, but a single DVD disc was capacious enough to contain the whole of Riven. |