I think it touches on two of the most fundamental aspects of human nature. We all like doing something constructive, where we can see that we are creating something from virtually nothing, and we all have a desire to nurture or look after things. This is what the game is all about. You spend hours painstakingly building your park and roller coasters up piece by piece, and then it becomes your own baby, which you want to look after and keep running smoothly, watching it grow in popularity and delighted by all the little guests who are enjoying all your hard work. Of course, the subject matter, roller coasters and theme parks, helps a lot as well. What could be more fun in a game than to build and run a park which is full of little people also having fun?

— Chris Sawyer

When Jeff Briggs, Brian Reynolds, and Sid Meier resigned from MicroProse Software in 1996 in order to found their own studio Firaxis, they left behind one heck of a parting gift. Civilization II, the last project Briggs and Reynolds worked on at MicroProse, became one of the rare computer games that sell in big numbers for months and months on end. Combined with a brutal down-sizing that involved laying off half the company and finally retiring the redundant Spectrum Holobyte brand, Civilization II managed to put MicroProse in the black in 1997 for the first time in more than half a decade. The $7.9 million profit the company posted that year, on revenues that were up by more than 40 percent, may have paled in comparison to the $120.2 million it had bled out since being acquired by the Spectrum Holobyte brain trust in December of 1993, but it was better than the alternative.

Unfortunately, Civilization II was a one-time gift. The departures of Briggs, Reynolds, and Meier, combined with the layoffs, completely destroyed any ability MicroProse might have had to come up with a similar game in the future. Meanwhile the action-oriented military simulators on which management had staked the company’s future in lieu of grand-strategy titles were proving a dud; with the Cold War and the Gulf War having receded into history, there just wasn’t the same excitement out there around such things that there once had been. Recognizing that the brief return to profitability was an anomaly rather than a trend, MicroProse’s CEO Stephen M. Race let it be known on the street that the company was up for sale, hoping against hope that a buyer with more money than sense would emerge before the rotten fundamentals of his business boomeranged back around to crush it. His hopes were gratified from a very unlikely quarter. Hasbro, which alongside its arch-rival Mattel ruled the American market for toys and family-oriented board games, took the bait.

Hasbro had been founded in 1923 in Rhode Island, by an industrious Polish immigrant named Henry Hassenfeld. It existed as essentially an odd-job factory until 1951, when the founder’s son Merrill Hassenfeld, who had inherited the enterprise after the death of his father, partnered with an inventor named George Lerner to create Mr. Potato Head. A bizarre idea on the face of it, it was a kit that children could use to dress up a potato or other vegetable of their choice with noses, ears, eyes, mustaches, glasses, hats, etc. (Later on, a plastic potato would be included as well to keep the tykes out of the pantry.) Thanks largely to savvy advertising (“The most novel gift in years, the ideal item for gift, party favor, or the young invalid!”), much of it on the brand-new medium of television, Mr. Potato Head became a sensation, selling millions upon millions and transforming its parent company forever. Indeed, Hasbro can be credited with inventing the modern industry of branded, mass-produced toys in tandem with Mattel, whose Magic 8 Ball made its debut at almost the same instant as Mr. Potato Head.

Many more toy-store successes were created or bought up by Hasbro over the ensuing decades: G.I. Joe, Transformers, Nerf guns, Play-Doh, Raggedy Ann and Andy, My Little Pony, Tonka trucks. Hasbro also collected an impressive stable of family board games, including such iconic perennials as Monopoly, Scrabble, Candy Land, Battleship, and Yahtzee. In 1996, the conglomerate’s revenues exceeded $3 billion for the first time. Remarkably, it was still in the hands of the Hassenfeld family; the current CEO was Alan Hassenfeld, a grandson of old Henry.

Yet despite the $3 billion milestone, Alan Hassenfeld was an insecure CEO. He had grown up as the free spirit — not to say black sheep — of the family, overshadowed by his more focused and studious older brother Stephen, who had been groomed almost since birth to be the heir apparent. But when Stephen died way too young in 1989, after just ten years in the top spot, the throne passed down to Alan. Stephen’s brief tenure had been by many reckonings the most successful period in Hasbro’s history to date; Alan felt he had a lot to live up to.

In particular, he was obsessed by the long-standing rivalry with Mattel, which, soaring on the indefatigable wings of Barbie, was growing even more quickly than Hasbro; Mattel’s revenues for 1996 were $3.8 billion. To add insult to injury, Hasbro had only narrowly managed to fend off a hostile takeover bid by Mattel the previous year. Alan Hassenfeld was looking for a secret weapon, some new market that he could open up to unleash new revenue streams, prove his mettle as CEO, and vanquish his enemy. He decided that his secret weapon might just be computer and console games and educational software.

Alas, Hasbro and Mattel always seemed joined at the hip, such that the one could never escape the orbit of the other. Alan Hassenfeld decided to set up a new division called Hasbro Interactive at the same instant that Mattel was also launching a push into software. Mattel Media scored a home run right out of the gate with Barbie Fashion Designer, the sixth best-selling computer game of 1996, despite being available for purchase only in the last two months of that year.

Like Mattel Media, Hasbro Interactive made games and edutainment products based on its panoply of well-known brands, selling them mostly through the same department stores that sold its toys and board games rather than through traditional software channels. Sometimes it bought licenses for other brands that had little appeal with the hardcore gamers being chased by most of the other big publishers, meaning that the digital rights could be picked up cheap; the television game shows Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune were among this group. The end results weren’t masterpieces of ludic design by any stretch, but they did what was required of them competently enough. Some were made for Hasbro by perfectly reputable studios, such as the Canadian Artech, whose history stretched back to Commodore 64 classics like Ace of Aces and Killed Until Dead. Hasbro Interactive’s biggest two titles of 1997 reflect the boundaries of its target demographic: a revival of the old quarter-eater Frogger for nostalgic children of the early 1980s and Tonka Search & Rescue for these people’s own kids.

So far, so uninteresting for the sorts of folks who read magazines like Computer Gaming World and self-identified as “gamers.” But then, in 1998, Hasbro Interactive made its presence known to them as well. In August of that year, it bought two companies: the moribund Avalon Hill, which had ruled the roost of paper-and-cardboard wargames during the 1960s and 1970s and had been trying without much success to adapt to the digital age ever since, and the equally moribund MicroProse Software. It paid $6 million for the former, $70 million for the latter, a deal which left most of the rest of the industry scratching their heads. And for good reason: its brief-lived window of profitability having well and truly slammed shut again by now, MicroProse was on track to lose $33.1 million in 1998 alone. Alan Hassenfeld, sitting in an office whose walls were covered with mid-century Mr. Potato Head memorabilia, seemed the very personification of the dilettantish, trend-hopping games-industry tourist, more and more examples of which species seemed to be entering the field as the industry continued to grow.

And yet the MicroProse deal would turn into a resounding success for Hasbro in the short term at least — not because Alan Hassenfeld was playing five-dimensional chess, but simply because he got very, very lucky, thanks to a reclusive Scottish programmer he had never heard of and would never meet.

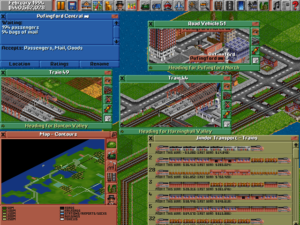

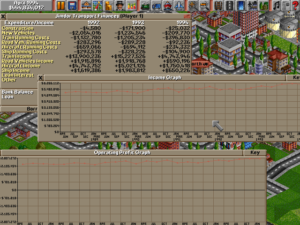

Transport Tycoon. Anyone who has played Chris Sawyer’s later and even more popular Rollercoaster Tycoon will recognize the family resemblance. The interfaces are virtually identical.

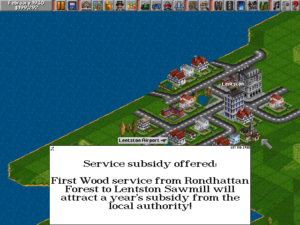

Back in 1994, MicroProse had published a game called Transport Tycoon, by a lone-wolf programmer named Chris Sawyer, who worked out of his home near Glasgow, Scotland. Building upon the premise of Sid Meier’s earlier Railroad Tycoon, it tasked you with building a profitable people- and cargo-moving network involving not just trains but also trucks, buses, ships, ferries, and even airplanes. Written by Sawyer in pure, ultra-efficient Intel assembly language — an anomaly by that time, when games were typically written in more manageable higher-level languages like C — Transport Tycoon was as technically impressive as it was engrossing. When it sold fairly well, Sawyer provided a modestly upgraded version called Transport Tycoon Deluxe in 1995, and that also did well.

But then Chris Sawyer found himself in the throes of a sort of writer’s block. He had planned to get started right away on a Transport Tycoon 2, but he found that he didn’t really know what to do to make the game better. In the meantime, he took advantage of the royalty checks that were coming in from MicroProse to indulge a long-running fascination with roller coasters. He visited amusement parks all over Britain and the rest of Europe, started to buy books about their history, even joined the Roller Coaster Club of Great Britain and the European Coaster Club.

One day it clicked for him: instead of creating Transport Tycoon 2, he could leverage a lot of his existing code into a Rollercoaster Tycoon, making the player an amusement-park magnate rather than a titan of transport. Granted, it had been done before; Bullfrog’s Theme Park had been a big international hit the same year that the original Transport Tycoon had come out. But that game didn’t let you design your own roller coasters from scratch, like Sawyer wanted to do, and it dripped with the laddish cynicism that had always been one of Bullfrog’s calling cards, regarding the visitors to your park more as rubes to be fleeced than customers to be pleased. Chris Sawyer wanted to make a more wholesome kind of game, aimed more at the tinkerer than the businessperson. “There’s a Lego-like philosophy to my games,” he says. “They’re games where you build things block-by-block in a rather simplistic and restrictive environment, and then interact with those models to keep things working well, improving and rebuilding things when needed and being rewarded for constructive skills and good management.”

So, working with exactly one part-time visual artist (Simon Foster) and one sound person (Allister Brimble), Chris Sawyer programmed Rollercoaster Tycoon from his home over two years of sixteen-hour days. He was the last of his kind: the last of the bare-metal assembly-language coders, and the last survivor from the generation of bedroom programmers who had once been able to get rich — or at least enriched — by making commercial computer games pretty much all by themselves and entirely on their own terms. When the game was just about finished, he gave it to his agent Jacqui Lyons, another survivor of the old days who had done much to create the legend of the British bedroom boffin back in 1984, when she had represented a pair of wunderkinds named David Braben and Ian Bell, organizing a widely covered publishers’ auction for their landmark creation Elite. She placed a bookend on the era now by taking Rollercoaster Tycoon to MicroProse, with whom her client had a prior relationship. This was just after the Hasbro acquisition, which may have made MicroProse ironically more receptive to such a light-hearted game than the previous, military-sim-obsessed management of the company might have been. At any rate, Jacqui Lyons didn’t have to stage another auction; the deal was done in short order. She ensured that the contract was written in such a way as to keep the Rollercoaster Tycoon trademark in the hands of Chris Sawyer; MicroProse merely got to license it. Neither she nor her client could possibly have realized what a fortune that stipulation would prove to be worth.

“I personally felt I’d achieved something worthwhile,” says the terminally modest Sawyer, “and I knew from the few testers who got to see the game early on that they were really enjoying playing it. However, the wider feeling was that it was always going to be a niche product, much more so than Transport Tycoon, and might not take off sales-wise at all.” MicroProse’s willingness to give it a shot was to a large extent driven by the fact that Sawyer was about to hand them what was essentially a finished game; this was a markedly different proposition from what had become the norm in the industry by now, that of a publisher agreeing to fund a project for some number of months or years, hoping that it didn’t get mired in development hell and finally came out the other end of the pipeline as good as the game that had been promised. Little did MicroProse know how extraordinarily well its bet would pay off, even without perpetual ownership of the trademark, another break with the industry norm.

Rollercoaster Tycoon was released on March 12, 1999, with almost no advance publicity and only limited advertising. The deal had come together so quickly that there had been no time to dangle previews before the magazines or engage in any of the other standard practices that accompanied a big new game, even had MicroProse wanted to. Nevertheless, one choice the publisher made would prove key to the game’s prospects. At that time, there were two typical price points for new first-run games. Big releases aimed at the hardcore set generally ran between $40 and $55, while budget titles — often derided as “Wal Mart games” by the hardcore, because so many of them sold best from that temple of the great unwashed Middle American consumer — ran about $15. Unsure where Rollercoaster Tycoon fit in, MicroProse elected to split the difference, giving it a typical street price of about $25. This move would prove to be genius — even if it was largely accidental genius. For in staking a claim right between the two opposing camps, it allowed Rollercoaster Tycoon to trickle up and down to reach both of them; the hardcore couldn’t dismiss it out of hand as lowest-common-denominator junk like the much-ridiculed Wal Mart staple Deer Hunter, even as casual players still saw a price they were just about willing to pay.

Of course, the price would have meant nothing if the experience itself hadn’t been compelling to an astonishingly broad range of people. When you stopped to think about it, you realized that your everyday Quake-loving teenager was actually pretty crazy about roller coasters as well, the more extreme the better. Meanwhile folks who were less enamored with hands-free loop-de-loops could focus on the other aspects of an amusement park. Tim Jordan, the owner of a software store in Eugene, Oregon, observed of Rollercoaster Tycoon that “there is something timeless and familiar about it. Everybody loves an amusement park, and the idea of being able to create your own had such a broad appeal. Mothers could get it for their kids, since it’s non-violent; kids might grab it because they like the idea of making their own rides; and adult strategists might get it for the challenge of making a viable economy in the park. A game like this doesn’t have to have the latest 3D-graphics engine to still keep the public’s attention.” On a similar note, Chris Sawyer himself remembers that “what became apparent to us early on was that the game was appealing to such a wide demographic — girls as well as boys, women as well as men, and people of all ages. And people were playing the game in different ways; some were just enjoying designing the flowerbeds and footpaths and making sure the guests were enjoying their stroll around the park, while at the opposite end some were pushing the limits of roller-coaster construction and creating the most technically amazing rides.”

A fellow named Greg Fulton, who had served as lead designer of New World Computing’s Heroes of Might and Magic III, was firmly within the hardcore-gamer demographic. His recollections of playing Rollercoaster Tycoon with his buddy Dustin Browder — a noted game designer in his own right — demonstrate its ability to win over just about everyone, whether they were after sweetness and light or death and mayhem. (I always hear Beavis and Butthead laughing in the background when I read this story…)

Scanning the terrain, Dustin clicked on a tall, narrow tower ride named “WhoaBelly.” It was a “drop tower” ride. After eight patrons filled the car at the bottom, the ride would shoot them to the top of the tower, then drop them back to the ground.

Dustin: “How about this one? We can change the height of the tower.”

Me: “Yeah. Add a bunch of levels.”

Dustin, adding several tiers: “I think that’s enough. Just the thought of this height is making me sick.”

Dustin found and surveyed additional options.

Dustin: “Okay. We can change the min and max wait time, wait for a full load, up or down launch mode, and the launch speed.”

Me: “Change the launch speed. Let’s see if we can make them vomit.”

Dustin, shaking his head, turned up the ride speed to its maximum: “90 miles per hour is as fast as it goes.”

Me: “That should do it. Let it rip.”

Dustin: “Shouldn’t we test it first?”

Me: “Nah. Just run it.”

Shrugging his shoulders, Dustin opened the ride to the park patrons. After ten or fifteen seconds, enough patrons had filled the ride car. It took off like a shot out of a gun and rocketed off the top of the tower, off the top of the screen.

Both Dustin and I sat there in stunned silence. A moment later, the car returned, crashed onto the top of the WhoaBelly tower… and exploded.

Across the bottom of the screen, a message flashed: “8 people have died in an accident on Tower 1.”

Dustin stifled a laugh. I wasn’t so mannerly and laughed out loud.

Dustin, looking back at me: “Did you know that would happen?”

Me, still giggling: “No. Not a clue. I had no idea it was even possible.”

Dustin: “I can’t believe they allowed us to do it.”

Me: “Well, I guess they didn’t have a choice. I mean, how would the game know when you were done building a roller coaster?”

Dustin, thinking about it for a second: “I wonder what else you could do.”

Me, excitedly struck with a burst of energy and inspiration: “Wait, wait, wait. I know. Give all the food away for free. Okay. Then charge $20 to use the bathrooms.”

Dustin, his mouth agape, squinted and glared at me, absolutely disgusted with what I had just proposed.

Me, still excited by my proposed idea, despite Dustin’s obvious revulsion: “Go ahead. Try it. It might work.”

Dustin, shaking his head with an exasperated snort: “All right, all right. Give me a second.”

Navigating to the first bathroom he could find, Dustin opened up the properties tab. Ironically, $20 was the maximum you could charge. He then dropped the price of various nearby food stalls to free. We waited, and within a minute or two, it was clear the patrons weren’t going for my “pump and dump” scheme.

Dustin: “It’s not working.”

Me, still hoping to make the idea work: “Maybe we’re charging too much. Cut the price in half.”

Dustin, shaking his head: “No. Nope. I think we’re done. I don’t wanna treat the park patrons like lab rats. I wanna play Diablo.“

Me, half laughing: “Okay. Okay.“

As the above attests, you can play Rollercoaster Tycoon cynically if you want to. Unlike the earlier Theme Park, however, it never pushes you to play that way. On the contrary, the core spirit of the game is pleasant and winsome. The graphics are full of cute little touches that capture the ambiance of those magical annual visits to Coney Island, Six Flags, Disney World, or Cedar Point that have become cherished childhood memories for so many of us. (Insert your own favorite amusement parks here if you grew up in Europe or somewhere else rather than the United States.) And the sound design is if anything even more evocative than the visuals; some of the sound effects were actually recorded by Chris Sawyer on location at real amusement parks. In its bright, juicy guilelessness, Rollercoaster Tycoon was a harbinger of the casual games still to come, coming before that aesthetic grew as stale from overexposure as the “gamer dark” audiovisuals of games like Diablo.

That said, there is one somewhat strange design choice in Rollercoaster Tycoon that I have to call out. Transport Tycoon had no campaign mode whatsoever, offering only a century-long free-play mode to test your logistical talents. Rollercoaster Tycoon, by contrast, responded to changing fashions in strategy-game design by offering nothing but a single-player campaign: no sandbox mode, no multiplayer, no standalone scenarios. Yet the campaign we do get is about the most minimalist one that could possibly have been implemented to still wind up with something to which that name could be applied. There’s no connecting tissue of story here, just an extended series of empty plots of land to build successive parks on, with goals that never go beyond abstractions like “have X number of guests by Y date” or “have park rating X and an annual income of Y.” The geography you must build upon gets more rugged and inhospitable as you progress, and more rides become available to research and construct, but that doesn’t keep the experience from becoming a little bit too samey for this player. I enjoyed tinkering with my first couple of parks; by the third one, I was starting to wonder if this was all there was to the game; by the fourth, I was more than ready to play something else. I had the same feeling that sometimes dogged me when playing Transport Tycoon: that this was a great game engine and a great setting for a game, just waiting for an actual game designer to come along and turn it into a real game.

Now, I hesitate to insist too stridently on the steps that should have been taken to “fix” Rollercoaster Tycoon, given that the game was one of the most breathtaking commercial successes of its era just as it was. Still, I can’t help but think about how much better the campaign might have been had Chris Sawyer partnered with a more conventional game designer. You could have come in as a fresh-faced junior amusement-park mogul, and faced a series of more interesting challenges that were given more resonance through a touch of narrative. Maybe a forest fire threatens your park in the Everglades; maybe your rival park one county over declares a roller-coaster arms race, and you have to pull out every plunge and curve and tunnel and loop you have in your toolbox in order to win the battle for hearts, minds, and butterfly-filled stomachs. These sorts of challenges could be woven through your construction of a mere handful of parks, instead of making you go through the same construction process from scratch over and over and over again. Of course, some people don’t want to play this way; they just want to set up the park of their dreams, fill it with the coasters of their dreams, and watch them all run. But for these people, why not just include a free-build mode, economy optional? The lack of such a thing in this of all games is fairly baffling to me.

Again, though, Chris Sawyer obviously did a lot of things very, very right to appeal to such a diverse cross-section of people, so take my carping with a grain of salt. All evidence would seem to indicate that, campaign or no, most people did approach Rollercoaster Tycoon more as a software toy than a ladder of challenges to be climbed. Just as a huge percentage of Myst players never got beyond the first island, quite a lot of Rollercoaster Tycoon players likely never got much farther than the first scenario in the campaign, and yet were left perfectly satisfied. Perhaps that was for the best. I’m loath to even guess how many hours it would take to actually complete the original game’s 21-scenario campaign, not to mention the two 30-scenario campaigns that followed in two expansion packs.

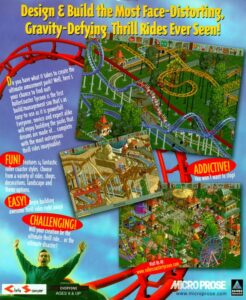

The picture of Chris Sawyer on the back of the Rollercoaster Tycoon box was taken on the real roller coaster Megafobia, at Oakwood Leisure Park in Wales. The amusement park agreed to run the coaster for several hours in the dead of winter so that Sawyer and his people could get just the photograph they wanted. Sawyer remembers that “it was so cold that we had to wait for the ice to melt on the track before the engineer would let the train run.” (There’s another amusing parallel with Elite here: fifteen years earlier, that game was introduced to the press at Thorpe Park, an amusement park near London, which was closed to the general public on that day so that the journalists could get their fill of the rides. When you’re looking for positive publicity, it never hurts to bribe the messengers…)

As you’ve no doubt gleaned by now, Rollercoaster Tycoon became a hit. A big hit. An insanely big hit. This didn’t happen right away, mind you. In the weeks after its release, it was greeted with surprisingly milquetoast reviews in the gaming press. But a demo which MicroProse was wise enough to make available spread far and wide on the Internet, and, lo and behold, the numbers the game put up increased month by month instead of falling off. By the Christmas buying season of 1999, Rollercoaster Tycoon had become a juggernaut, a living demonstration of the pent-up demand that existed out there for games that didn’t involve dragons, aliens, or muscle-bound men in combat fatigues, yet were not intelligence-insulting schlock like Deer Hunter either. Belatedly waking up to the fact that it had a sensation on its hands, Hasbro finally began advertising the game widely, on the same Saturday-morning television and in the same glossy family magazines where it plugged its toys. The game sold more than 4 million copies in three years in the United States alone, single-handedly justifying all of the money Hasbro had paid for an ailing MicroProse. And that’s without even considering the two best-selling expansion packs, or 2002’s Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 — another lone-wolf production from Chris Sawyer — and its own two expansion packs. For a good half a decade, Rollercoaster Tycoon was simply inescapable.

The biggest hit by far that MicroProse had ever published, Rollercoaster Tycoon was ironically also very nearly the last. Beyond Chris Sawyer’s fortuitous bolt out of the blue, MicroProse’s output as a subsidiary of Hasbro was marked by attempts to computerize old Avalon Hill board games like Diplomacy and Squad Leader, along with military sims like Gunship! and B-17 Flying Fortress, tired would-be successors to the games that had built the company under Sid Meier and “Wild” Bill Stealey. They would have felt anachronistic at the turn of the millennium even had they been good, which they generally were not. The one other slight bright spot was the moderately successful Majesty: The Fantasy Kingdom Sim, a real-time-strategy game which did manage to feel contemporary. Like Rollercoaster Tycoon, it was developed by an outside studio and only published by MicroProse. A couple of lucky breaks aside, the broader question of just why Hasbro had acquired MicroProse remained unanswered.

Nevertheless, the incredible sales of Rollercoaster Tycoon encouraged Alan Hassenfeld to dream bigger dreams than ever for Hasbro Interactive, as did the actions of Mattel, who in the midst of the current dot.com frenzy had acquired The Learning Company, the biggest name in educational software, in a blockbuster deal worth more than $3.5 billion. (The deal included Broderbund Software, itself bought by The Learning Company the previous year; its nearly two-decade-long legacy included such bestselling standard bearers of the industry as Choplifter!, Lode Runner, Carmen Sandiego, SimCity, Prince of Persia, Myst, and Riven, alongside cult classics like Mindwheel, The Last Express, and The Journeyman Project 3. It was retired as a publishing label after the Mattel acquisition.) Hasbro too went shopping, collecting a wide array of digital licenses, from Pac-Man to Formula 1 auto racing. It spent $100 million to open a state-of-the-art hub for its software developers in Silicon Valley, and even made a serious bid to buy Electronic Arts, the biggest American games publisher of them all.

Positively reeking of tourism as it did — Alan Hassenfeld entrusted the day-to-day supervision of his software division to his COO Herb Baum, most recently of that well-known purveyor of digital technology and entertainment Quaker State Oil — Hasbro struggled mightily to convince credible developers to come to its shiny new complex. Those that did tended to deliver sub-par products late and over-budget. Thanks to Hasbro Interactive’s ocean of red ink, and notwithstanding the ongoing Rollercoaster Tycoon phenomenon, the company as a whole lost money in 2000 for the first time in twenty years. The stock price plunged from $37 to $11 in just twelve months. The dot.com bubble was bursting, and investors suddenly wanted no part of Hasbro’s digital dreams and schemes; they wanted the company to turn its focus back to physical toys and board games, the things it knew how to do. At the end of 2000, a pressured Alan Hassenfeld sold all of his software divisions, MicroProse among them, to the French games publisher Infogrames for $100 million. One has to presume that a good part of the reason Infogrames was willing to pay such a price was Rollercoaster Tycoon, whose sales were not just holding steady but actually accelerating at the time as it spread into more and more international markets. Then, too, Chris Sawyer was already under contract to provide Rollercoaster Tycoon 2.

For Alan Hassenfeld, there was just one silver lining to his bold, would-be reputation-making initiative that had turned into a fiasco. And that was the fact that Mattel’s acquisition of The Learning Company had proven to be a disaster of a whole other order of magnitude, reflecting a failure of due diligence on a potentially criminal scale. The Learning Company began reporting huge losses almost before the ink was dry on the acquisition paperwork. Hemorrhaging cash from its ailing subsidiary and facing legal threats from its shareholders, Mattel agreed to pay — yes, pay — a “corporate turnaround firm” known as Gores Technology Group $500 million to take the albatross from around its neck only eighteen months after the purchase had been made. It would cost another $122 million to settle the shareholder lawsuits that resulted from what Funding Universe describes as “one of the biggest corporate blunders ever.” Mattel’s stock ended the year 2000 at less than $10, down from a recent peak of $45; it posted a net loss for the year of more than $400 million. Alan Hassenfeld must have felt like he had gotten off comparatively lightly. Badly shaken but far from destroyed, both Hasbro and Mattel vowed to their shareholders to put their digital fever dreams behind them and get back to doing what they did best. Now as ever, the two giants of American toys seemed doomed to walk in lockstep.

Alas, MicroProse was not so lucky. Seeing little remaining value in the brand, Infogrames decided to phase it out. Thus when Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 appeared in 2002, it bore only the name of Infogrames on the box. (The sequel sold almost as well as the original, despite complaints from reviewers that it improved on its predecessor only in fairly minimal ways.) MicroProse’s old office in Hunt Valley, Maryland, whence had once come a stream of iconic military simulations and strategy games for a generation of Tom Clancy-loving boys and young men, was kept open for a couple of years more to make the little-remembered Xbox game Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes. But it was officially shuttered in 2003, as soon as that project was complete, to bring the final curtain down on the story that had begun with Sid Meier’s Hellcat Ace back in 1982. Ah, well… just about everybody could agree that the best parts of that story were already quite some years in the past. I’ve said it before in the course of writing these histories, but it does bear repeating: whimpers are more common than bangs when it comes to endings, in business as in life.

As for Chris Sawyer, that modest man who came up with a hit game big enough to gratify an ego a hundred times the size of his own: he followed up Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 in 2004 with Locomotion, which was his long-delayed Transport Tycoon 2 in all but name. Unfortunately, his Midas touch finally deserted him at this juncture. Locomotion was savaged for looking and playing like a game from ten years ago, and flopped in the marketplace. Deciding that his preferred working methods were no longer compatible with the modern games industry, he licensed the Rollercoaster Tycoon trademark which Jacqui Lyons had so wisely secured for him to the studio Frontier Developments — helmed by David Braben of Elite fame, no less! — and ambled off the stage into a happy early retirement. “It was time to change priorities, take a break, reduce the workload, and put a bit more time and effort into my personal life and other interests rather than spending sixteen hours a day in front of the computer,” he says.

Traveling the world to ride roller coasters remains among his current interests — interests which his wealth from Rollercoaster Tycoon allows him to indulge to his heart’s content. He still surfaces from time to time on the Internet, whether to promote mobile versions of his old games or just to chat with a lucky member of his loyal fandom, but these occasions seem to be ever fewer and farther between. “I’m really not into self-promotion and not sure I can actually live up to the mythical character the online community sometimes perceive me as,” he said a little ruefully on one of them. It seems pretty clear that the game-development chapter of his life is behind him. The last of the British bedroom boffins has moved on.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Games That Sell! by Mark H. Walker and Toy Wars: The Epic Struggle Between G.I. Joe, Barbie, and the Companies That Made Them by G. Wayne Miller. Computer Gaming World of August 1996, July 1999, July 2002, and January 2003; PC Zone of April 1999; Retro Gamer 138 and 198. Also the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth case study on Hasbro Interactive, written by Professor Chris Trimble, and the Her Interactive archive held at the Strong Museum of Play, which is full of interesting information about those parts of the millennial games industry that didn’t cater exclusively to the hardcore demographic.

Online sources include Wesley Yin-Poole’s interview with Chris Sawyer for EuroGamer, Chris Sawyer’s personal website, and the Funding Universe history of Mattel. The dialog between Greg Fulton and Dustin Browder is taken from a newsletter the former sent out in association with a now-abandoned attempt to create a successor to Heroes of Might and Magic III. And thanks to Alex Smith for setting me straight on a few things in the comments after this article was published, as he so often does.

Where to Get Them: Rollercoaster Tycoon Deluxe, Rollercoaster Tycoon 2: Triple Thrill Pack, and Locomotion are all available as digital purchases on GOG.com.