At the conclusion of my previous article on Sierra Online’s corporate history, we saw how Ken and Roberta Williams moved their company’s headquarters from the tiny Northern California town of Oakhurst to the Seattle suburb of Bellevue, home to Microsoft among others, in September of 1993. They did so for a mixture of personal and professional reasons, as Ken has since acknowledged. Their children were getting older, for one thing, and the schools in Oakhurst were far from world-class. Additionally, life in general as the biggest fish of all in the fishbowl of a company town that Oakhurst had become wasn’t always pleasant; for example, Ken has claimed that his kids were at times bullied by “the children of former Sierra employees who had a grudge against Sierra.” Some other former employees suspect still another reason for the move to Bellevue, one that Ken neglects to mention: the fact that Washington State had no personal income tax, while California’s was the highest in the nation.

Still, there are no grounds to doubt that the public reason Ken gave for the move back in the day was indeed a major part of the calculation: the need to recruit the sort of seasoned business talent that could take Sierra to the next level. The company’s annual revenues had grown every single year since 1987, more often than not substantially, and this was of course wonderful. But less wonderful was the fact that profits had never been as high as that progression would imply; Sierra had a knack for spending almost every dime they earned. Of late in fact, the bottom line had dipped sharply into loss territory even as revenues continued their steady climb. Under pressure from his shareholders, Ken Williams realized that he had to find a way to make his company start to pay off. He believed that doing so must entail assembling the kind of top-flight management team which could only be found in a big city. He’d been seeking a rock star of a chief financial officer for a long time from Oakhurst to no avail. Ken Williams:

I had hired a San Francisco-based company, Heidrick & Struggles, to lead the search, and after months of getting nowhere I called my contact at Heidrick in frustration. “Why do you keep sending me B and C level candidates?” I asked. I was tired of having my time wasted interviewing candidates who were not at the level I was seeking. The answer came back without hesitation: “Ken, you’re aren’t getting it. No A player wants to move to Oakhurst.”

Nine months after the move to Bellevue, Ken finally found his rock star in the form of one Mike Brochu, a financial whizz who had spent the last nineteen years working for Burlington Resources. The man whom Ken still describes as “probably the best hire I ever made” was a garrulous Texan who “inspired confidence in everyone around him.” Not coincidentally, Sierra began to display a newly hard-nosed, bottom-line-focused attitude toward their business from virtually the moment of his arrival. As one of his first projects, Brochu led the negotiations that resulted in the sale of The ImagiNation Network, Sierra’s visionary but perpetually money-losing online-gaming service, to AT&T for $40 million in cash in November of 1994.

Meanwhile Sierra implemented a significant shift in their product-development strategy. For many years now, the heart of the company’s identity had been a set of long-running adventure-game series, most of which worked the word “quest” somewhere into their title. Dodgy from the standpoints of both writing and design though they sometimes were, they’d all displayed enough lovable qualities to worm their way into fans’ hearts. I’ve described in earlier articles how Sierra fandom could feel like belonging to a big extended family. These games, then, were the cousins whom you could always expect to see at the family reunion every couple of years, dressed perhaps a bit differently than last time around but always the same person at bottom. They were comfortingly predictable, and that was exactly how the fans liked them.

But for all that these ramshackle, puzzle-heavy adventure games were good at cementing the loyalty of the already converted, they were less equipped to unleash the sort of explosive growth Sierra was now after. It was a pivotal moment in the history of the personal computer, as Ken Williams and Mike Brochu well recognized. In 1994, more home computers would be sold than televisions, as consumers, tempted by the ease of use of Microsoft Windows, the magic of multimedia, and rumors of a thing called the World Wide Web, jumped onboard the computing bandwagon in staggering numbers. These people didn’t know a King’s Quest from an Ultima. Reaching them would require a different sort of game: fresher, hotter in the Marshall McLuhan sense, more in tune with what they were seeing on television and at the movies. It seemed like it was now or never for Sierra to capture their interest, even if it meant that some of the old fans were left feeling a bit abandoned.

So, Sierra’s new Bellevue management team took a hard look at their existing series in order to decide which were expendable and which were not. King’s Quest, the company’s longstanding flagship series, which already enjoyed a measure of name recognition outside the traditional computer-gaming ghetto, would have been an obvious keeper even if it hadn’t been the baby of Roberta Williams. Leisure Suit Larry also had proven appeal with non-traditional demographics, and was thus also a no-brainer to keep around. Space Quest was an edge case, but the managers decided to green-light one more game, if only to throw a bone to the old-school fans. But Police Quest would get revamped from a line of adventure games into a line of tactical 3D action games, while Quest for Glory would get the axe entirely. Going forward, the main focus would be on bigger-budget adventures employing filmed human actors, for which Sierra was now building their own sound stage down in Oakhurst at considerable cost. They would make fewer of this new type of adventure, but each of them would be a flashy, high-fidelity production, able to appeal to a mass market weaned on big-screen televisions and CD players. The idea was to make the release of each Sierra adventure from now on a real event.

Unfortunately, the transition from one product strategy to another came with a pitfall: it would take some time to bring it off, meaning that 1994 would be an unusually quiet year in terms of new games. And that reality, combined with the new management team’s more hard-nosed attitude, meant that some of the folks in Oakhurst must lose their jobs. Among them were Corey and Lori Cole, the husband-and-wife team behind Quest for Glory, who saw their roles cancelled along with the fifth game in their series, the most impressive of all the series in the Sierra lineup in terms of design ambition and innovation. Corey recalls a scene which made it all too clear to everyone present that Sierra was now being run as a business, not a family: “All employees in the meeting were handed envelopes; about half of them contained ‘pink slips’ notifying them that they no longer worked for Sierra. Those employees were escorted back into the building and watched as they retrieved personal belongings from their desks.” Layoffs are never easy. Corey especially remembers the sight of Gano Haine, who had worked on Sierra’s two EcoQuest games and Pepper’s Adventures in Time, standing in the parking lot crying: “Sierra had been her dream, and she was so thrilled to have gotten the job there.”

During this year of wrenching transition, Sierra released just one new Oakhurst-built adventure game, making it their least prolific year in that respect in almost a decade. Thankfully for the bean counters, the game in question was the latest installment in Sierra’s most bankable adventure series of them all. King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride was a typical entry in a series that had been Sierra’s ever-evolving technological showpiece since 1984. But then, that description in itself implies innovation on at least a technical front, and this the new entry certainly delivered.

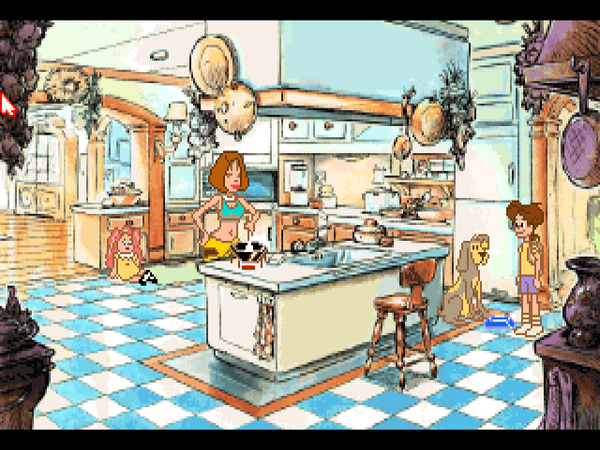

The King’s Quest VII opening movie. Ken Williams has often said that Walt Disney was one of his biggest role models. With King’s Quest VII, this influence became almost distressingly literal.

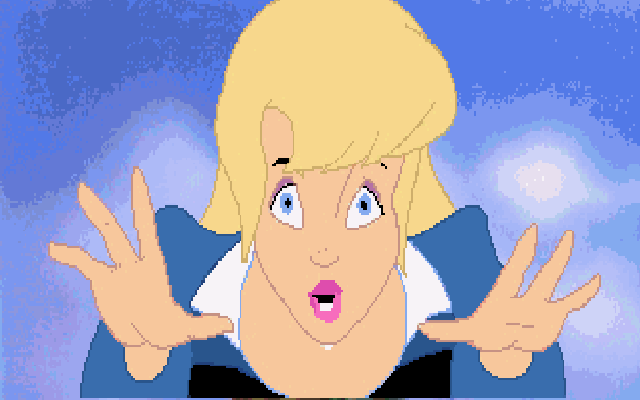

Although it did not employ filmed actors, King’s Quest VII was indicative in another way of Sierra’s new direction: rather than an interactive movie, it aimed to be an interactive cartoon worthy of comparison to the likes of Disney, an ambition which required it to look beyond Sierra’s own stable of talented in-house artists for some of its visuals. Ken Williams first reached out to an up-and-coming animation studio known as Pixar. He even spoke personally with Steve Jobs, Pixar’s chairman and majority owner, but in the end the studio proved to be simply too busy working on Toy Story, their first full-length feature film, to take on this task as well. So, Sierra ended up contracting sequences out to no fewer than four other outside animation studios, in addition to employing their own artists to create what truly was an audiovisual extravaganza by the standards of its time. King’s Quest VII went full Disney, as Charles Ardai described in his review for Computer Gaming World magazine.

I tried this game on my mother (a big fairy-tale fan), who asked, “Is that a game from Disney?” When I replied in the negative, she said, “But they’re trying to do Disney, right?”

They are indeed. From the opening frames, where drops of dew in an enchanted forest drop on the tummy of an enchanted ladybug, to the scene a few seconds later in which lovely Princess Rosella sings her royal heart out in a tuneful paean to her about-to-be-lost adolescence, King’s Quest VII exudes Disney-like quality from each of its cel-animated poses.

Every frame is beautiful, every line is neat and pert, the camera soars and glides, and the notes of the musical score tinkle out in bounding effervescence like the fizz out of a bottle of soda pop. This is the Disney of The Little Mermaid or Beauty and the Beast, or Aladdin, if you deduct that film’s adult-targeted sense of irony. It’s the Disney of The Sword in the Stone and of Alice in Wonderland, light and fluffy as a soufflé. It’s not the Disney of Bambi or Snow White; here even the menaces are adorable bits of whimsy. If the villains ever frighten, it’s only for a brief time, and then everyone gets together again for one more song.

It matters not at all that the game is from Sierra rather than Disney. It is true to the Disney spirit.

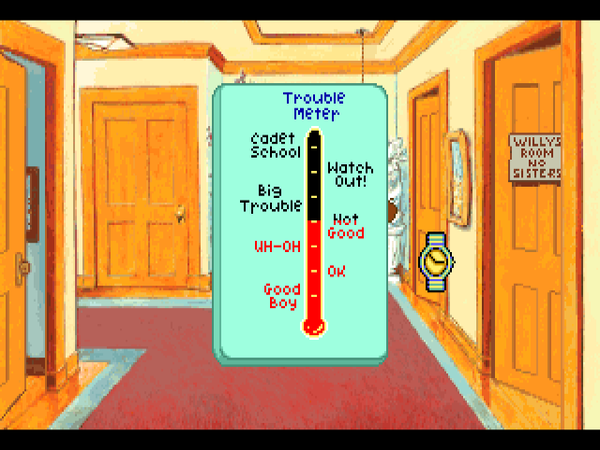

Along with the mouth-watering new look, the game showed some welcome design evolution over Roberta Williams’s earlier work. Four years after LucasArts’s The Secret of Monkey Island had pointed the way, King’s Quest VII finally managed to free itself from the countless hidden dead ends that had always made playing a Roberta Williams game feel like playing make-believe with a sadist. Player deaths, on the other hand, were still copious, and still so unclued as to be essentially random, but were now at least relatively painless. Rather than expecting you to save every five minutes, the game was now kind enough to return you to the point you were at before you were so foolish as to look at the wrong thing or dilly-dally in the wrong room a second too long. In fact, save files as such disappeared altogether; exiting the game now automatically bookmarked your progress.

These changes all existed in the name of making the game more welcoming to brand new players, out of the hope that they could be convinced to give it a try despite the ominous Roman numeral after its name. To further emphasize that this was a kinder, gentler King’s Quest, it used a radically simplified interface built around a one-click-does-it-all mouse cursor. More oddly, Sierra made it possible to play any of its chapters at any time, meaning you could start with the climax and work backward to the prologue if you were so inclined. (The real point of this feature, of course, was to let you watch each chapter’s opening movie without having to get your hands dirty with the actual game, if you happened to be one of the many people who typically bought each new King’s Quest as a tech demo for their latest computer.)

But alas, in other ways this latest entry really was just another King’s Quest. The writing from Roberta Williams and Lorelei Shannon, her latest apprentice co-designer, was the usual scattershot blend of fairy-tale and pop-culture ephemera, lacking sufficient wit or imagination to be all that compelling even as pastiche, while the puzzle design was made less infuriating than usual only by the lack of dead-player-walking situations. Both the writing and the puzzles got noticeably worse as the game wore on, evidence perhaps of a lead designer who was feeling increasingly bored with her big series, and was in fact already working on her next, very different game. All of this was doubly disappointing coming on the heels of King’s Quest VI, a game which had seemed to herald a series that was at last beginning to take its craft a bit more seriously. Even the much-vaunted look of King’s Quest VII, although impressive in its individual parts, made for a rather discordant jumble when taken in the aggregate, being the work of so many different teams of animators.

Nevertheless, King’s Quest VII sold very well upon its release in November of 1994, as games in the series always did. Meanwhile Dynamix, the most consistent of Sierra’s subsidiary studios, delivered solid performers in the non-adventure games Aces of the Deep, Front Page Sports: Football ‘Pro 95, and Metaltech: EarthSiege. Most of all, though, it was the ImagiNation windfall that turned what would otherwise have been an ugly year into one that actually looked pretty good on the bottom line: $83.4 million in revenues, up from $59.5 million in 1993, with an accompanying $12 million profit, in contrast to an $8.6 million loss the previous year. Now it was up to the new product strategy to keep the party going in 1995.

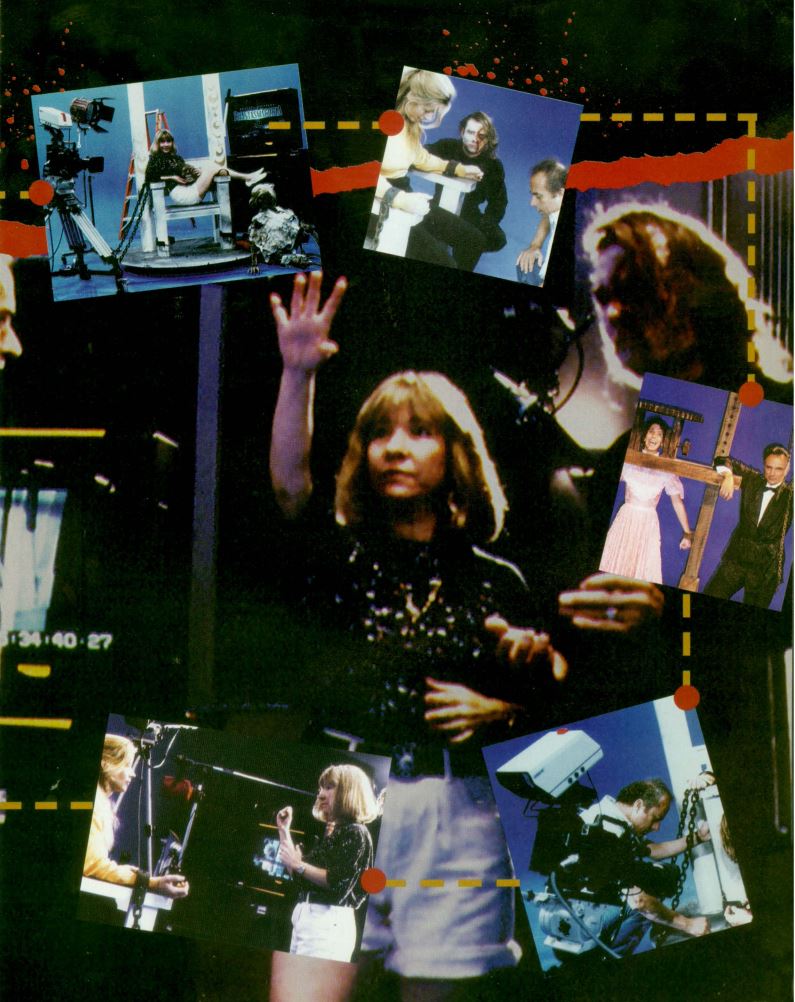

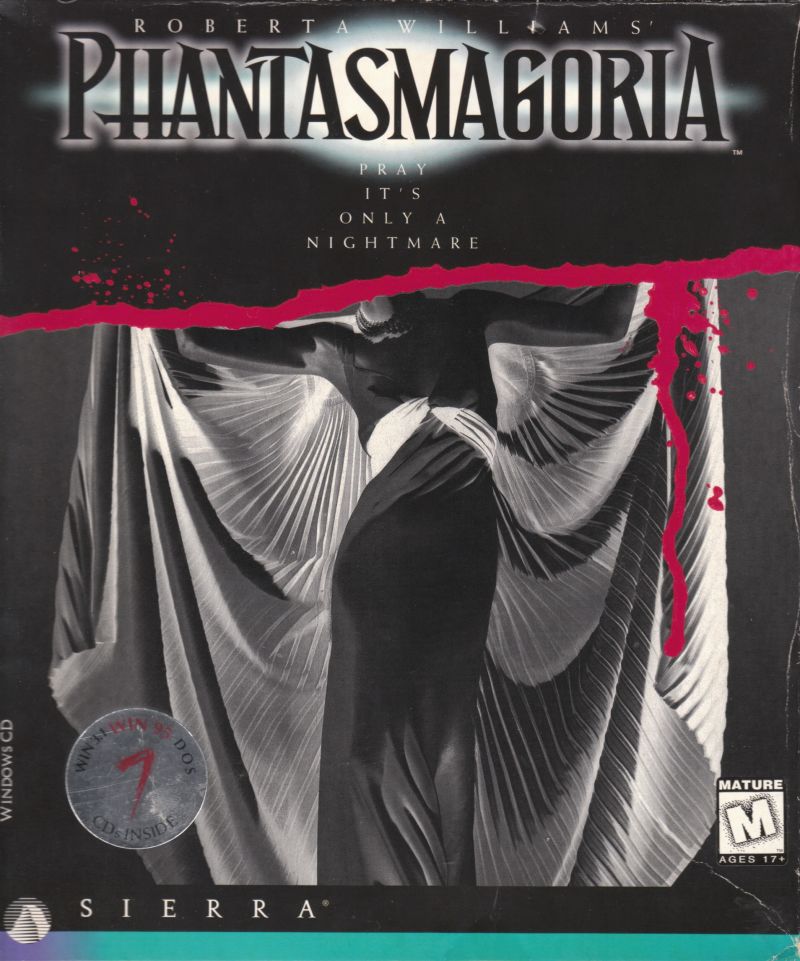

The first big test of that strategy was to be the game that Roberta Williams had been working on concurrently with King’s Quest VII. Phantasmagoria would take full advantage of the Oakhurst sound stage Sierra had just built. It was to be a play against type worthy of any pop diva: Roberta, the family-friendly “queen of adventure gaming,” was going dark and sexy. “With Phantasmagoria,” wrote Sierra’s marketers, “Roberta Williams has created a superbly written interactive story, fraught with horror and suspense, and totally in the player’s control at all times.” Bill Crow, the mastermind of Sierra’s new sound stage, believed that “Phantasmagoria is going to open the market to a much broader audience of game players. We’re now starting to deliver an audiovisual experience that’s much closer to what the average consumer can relate to.” With Phantasmagoria, in other words, computer games were about to burst out of their nerdy ghetto to become sophisticated entertainments for discerning adults.

How times do change. Today Phantasmagoria is more or less a laughingstock, a tidy microcosm of everything that was wrong with the full-motion-video era of adventure games. In truth, some of its bad rap is a bit exaggerated; it’s not really any worse than dozens of other similarly dated productions of the mid-1990s. Certainly plenty of other games had equally cheesy acting, equally clueless writing, and equally trivial gameplay. Phantasmagoria‘s modern reputation for hilarious ineptitude stems to a large extent from its mainstream prominence in its heyday. The wave of hype that Sierra unleashed, much of it issuing from the mouth of Roberta herself, is catnip for snarky reviewers like yours truly, who can’t help but throw it all back in her face. “I want to explore games with a lot of substance and deep emotions,” Roberta said. But Phantasmagoria is so very, very much not that kind of game. If you squint just right, you can see what she was trying to create: a game of claustrophobic psychological horror, an interactive version of The Shining. But alas, nobody involved had the chops to pull it off.

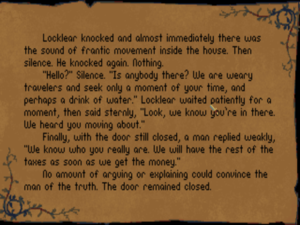

Phantasmagoria revolves around a couple of artsy newlyweds named Adrienne and Don, a novelist and a photographer respectively. As the story begins, they’ve just moved into a rambling old mansion on a sparsely inhabited island off the coast of New England. They’re the first people to attempt to live in the house, we soon learn, in almost a century. The last person to do so before them was a strange stage magician named Carno the Magnificent, who went through pretty young wives at a prodigious rate — all of them abruptly disappearing from the island, never to be seen again. In the end, Carno himself disappeared, and that was that for the house until our heroes turn up. It comes as a surprise to absolutely no one except them when the place turns out to be haunted by a malevolent spirit. It quickly begins to take over the mind of Don, leaving Adrienne, the character the player controls, to try to sort out the mystery before her husband murders her like Carno killed all of his wives.

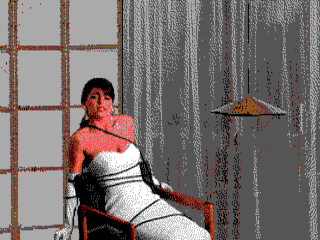

Somewhat surprisingly in light of Sierra’s mass-market aspirations, they never attempted to hire “name” actors for Phantasmagoria in the way that Origin Systems was doing at the time for the Wing Commander franchise. The role of Adrienne went to Victoria Morsell, whom Sierra rather ambitiously described as a “film, TV, and theater star,” having apparently confused bit parts with starring ones. Still, she does a decent job within the awkward constraints of her task. David Homb in the role of Don, on the other hand, is just awful; his wooden performance comes off as more creepy before the horror starts, when he’s trying to play a loving husband and failing at it abjectly, than it does after his head starts metaphorically spinning around. The rest of the cast is a similarly mixed bag.

Sierra hired a director named Peter Maris, with a long run of schlocky ultra-low-budget films behind him, for a shoot that wound up taking fully four months. Even given that his oeuvre wasn’t exactly of Oscar caliber, his complete disregard for pacing is bizarre. Phantasmagoria‘s seven CDs — yes, seven — are filled with interminable sequences where Adrienne disassembles a brick chimney piece by piece, or breaks through a wooden door board by board, or applies her morning makeup layer by agonizing layer. Indeed, Adrienne insists on stopping and preening herself at each of the many mirrors in the house throughout the game, and we’re forced to watch and wait while she does so, hoping against hope that something interesting might happen this time around. (For all of Roberta Williams’s status as a female pioneer in a male-dominated industry, her games’ view of gender isn’t always the most progressive.) All of this, combined with the clumsy, overly wordy script, makes the game seem much longer than the few hours it actually takes to play. There’s a (bad) 90-minute horror flick worth of plot-advancing footage here at the best; Sierra could easily have ditched three of the seven CDs without losing much at all.

The much-vaunted “adult” content is rather less than it’s cracked up to be. The opening movie includes the least sexy sex scene in the history of media. Ken Williams says that it was originally to have shown Adrienne topless, but Sierra lost their nerve in the end: “When it came time to release the game, we edited it to only show some side boob.” Given how weird and awkward it already is, we can only be thankful for their last-minute fit of prudishness.

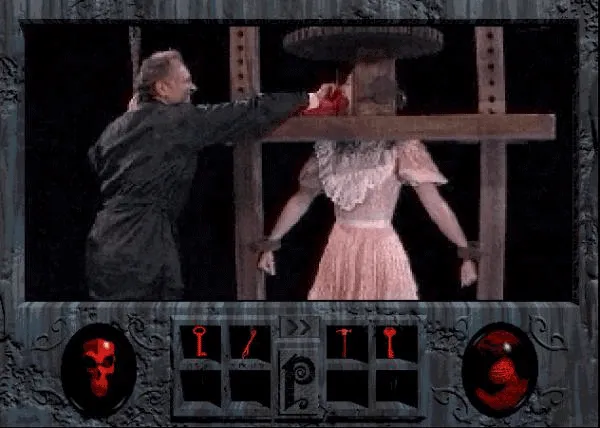

Nor is the game remotely scary, although it does get gruesome — a very different quality — from time to time. These sequences come when Adrienne is visited by visions of the murders that took place long ago in the different rooms of the house, or, in the latter stages of the game, when she herself meets an unfortunate end thanks to a failure on the player’s part. For better or for worse, the methods of murder might just be the most creatively inspired parts of the game: Carno kills one wife by sticking a funnel into her mouth and stuffing disgusting offal down her throat, another by shackling her into a machine that twists her head around until her neck snaps, while Adrienne can get her head sliced in two by an axe blade or her face literally ripped off by a demon. These scenes are certainly gross and shocking in their way, but it’s all strictly B-movie-slasher fare — Friday the 13th Part V rather than the Shining vibe Roberta was going for.

The scene which prompts by far the most discussion today takes place out of the blue one morning, when Don creeps up behind Adrienne at her bedroom mirror and proceeds to… well, to rape her. Needless to say, this is a disturbing place for even an adults-only game to go. Roberta Williams is hopelessly out of her writerly depth here; in contemporary interviews, she seems utterly oblivious to the real trauma of rape, describing the scene as nothing more than a plot device to show Don’s descent into evil. Its one saving grace is the fact that no one involved is up to the task of making the rape seem remotely realistic; Don humps and thrusts a bit without ever actually taking his boxer shorts off, and that’s that. (One can only hope that Sierra didn’t shoot a more explicit version of this scene…) Afterward Adrienne, rather in contrast to Roberta’s stated desire to explore “deep emotions,” just cleans herself up and gets on with her day, apparently none the worse for wear. Even amidst the more lackadaisical sexual politics of 1995, the scene prompted considerable discussion and a measure of public outrage here and there. Australia’s Office of Film and Literature Classification refused to accept the game because of it, with the result that it was effectively banned from sale in that country.

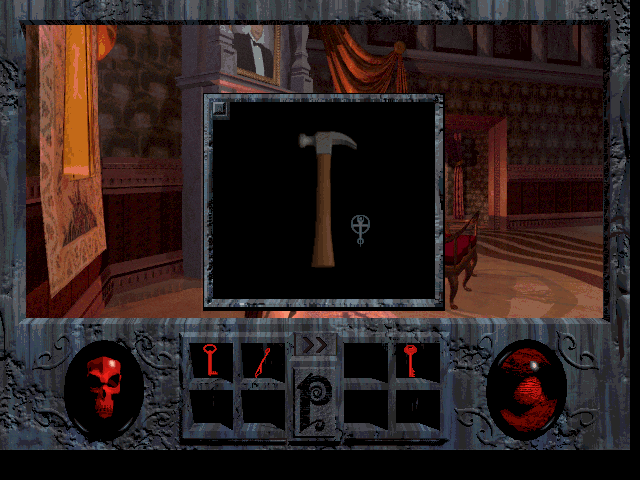

So much for Phantasmagoria the movie. In terms of gameplay, it isn’t up to all that much at all. Its reliance on canned snippets of static video dramatically limits the scope of its interactivity, while its determination to be as accessible as possible means that all of its puzzles are broadly obvious; a version of that tired old adventure saw, the locked door with a key in the keyhole on the other side and a handy nail and newspaper, is about as complicated as things ever get. The simplified interface from King’s Quest VII makes a return, it’s once again possible to play the chapters in any order you choose, and bookmarks once more replace save files in the game’s terminology, although it is at least possible to make your own bookmarks whenever you like now.

In a way, all of this is a blessing: it lets you power right on through Phantasmagoria, laughing at it all the while, without getting hung up on the design flaws that dog most of Roberta Williams’s games. I’m not generally a fan of high camp, but even I could probably enjoy Phantasmagoria with the right group of friends. If ever a game was ripe for the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment, it’s this one.

Note the ESRB rating at the bottom right of the Phantasmagoria box. In the face of the internecine split over rating systems among computer-game publishers, Sierra generally backed the ESRB over its rival the RSAC. (The much more extreme sequel-in-name-only Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh would go with the RSAC in order to avoid the ESRB’s dreaded “Adults Only” rating, which most retailers refused to touch.)

Objects in your inventory can be viewed as rotatable 3D models, a capability that debuted in King’s Quest VII. Indeed, Phantasmagoria‘s environments were all built using 3D-modeling software rather than being hand-drawn pixel art. This is the only way Sierra could possibly have included more than 1000 different views in the game, as their marketers proudly told anyone who would listen; the typical old-style Sierra adventure had less than 100. But the new approach didn’t lead to increased environmental interactivity — rather the opposite, I’m afraid.

Adrienne with psycho-hubby Don. Both wear the same clothes for all seven days of the game, a fact that has prompted much joking over the years. This was judged necessary so that the developers could mix and match video sequences as needed. The outfit that Adrienne wears is actually the one that Victoria Morsell, the actress who portrayed her, just happened to turn up in on the first day of filming. “By the time the filming for Phantasmagoria was complete,” wrote Sierra in their customer newsletter, “duct tape, patches, and prayers were all that held Tori’s pants together. She had worn them to the set every single day of the fifteen weeks of filming.”

One of Carno’s ingenious execution devices. Sierra had these props built by local Oakhurst craftsmen, prompting much discussion in the town about just what it was they were up to inside the building that housed their sound stage.

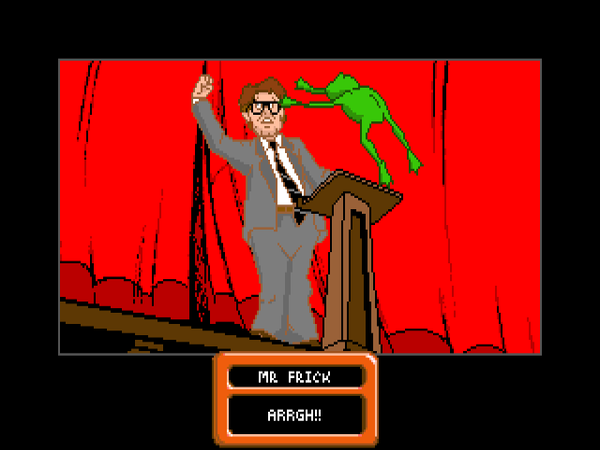

The real horrors of Phantasmagoria are Harriet and her son Cyrus, a pair of bumpkin ingrates who are meant to serve as comic relief. They’re exactly as unfunny as this screenshot looks.

But that, of course, is now. When it was released in the summer of 1995, accompanied by the most lavish marketing campaign Sierra had ever sprung for, Phantasmagoria was hailed as the necessary future of gaming — and not just by Sierra’s own marketers. All of the drawbacks of its technical approach, which would have still been present even with better writing, designing, acting, and directing, were overlooked by industry scribes eager to see the fusion of Silicon Valley and Hollywood. “For horror fans,” wrote Computer Gaming World, “Phantasmagoria is a signal event, one of the most powerful titles ever released in the genre, and easily the most single-mindedly horrific.” In a fit of exuberance, Roberta Williams let slip her dream of becoming “the Steven Spielberg of interactivity.” Thus she must have reveled most of all in the mainstream-press coverage. USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, and Billboard all gave the game positive reviews; “Hotly awaited and, well, just hot, Phantasmagoria lives up to the advance billing,” wrote the last. Notices like these easily made up for the refusal of some squeamish retailers, among them the national chain Comp USA, to stock the game at all.

Every article was sure to mention the game’s budget of fully $4 million, an absolutely astronomical sum by the standards of the time, and one which Sierra too trumpeted for all it was worth in their advertising. In truth, much of that money had gone into the building of the Oakhurst sound stage that Sierra planned to use for many more games, but no one was going to let such details get in the way of a headline about a $4 million computer game. Phantasmagoria became a massive hit; its sales soared past the magic mark of 1 million units and just kept right on going. It was a perfect game to take home with a shiny new computer, the perfect way to show your friends and neighbors what your new wundermachine could do. The window of time in which a game like this could have success on a scale like this was to prove sharply limited, but Phantasmagoria managed to slip through behind Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, The 7th Guest, and Myst just before said window slammed shut. It would prove the last such sparkling success among its peculiar species of game.

But what a success it was while it lasted. Phantasmagoria still stands as the best-selling game ever released by an independent Sierra. Small wonder that Ken and Roberta Williams both remember it so fondly today. Rather than a laughingstock, they remember Phantasmagoria as a mainstream-press darling and chart-topping hit, and love it for that. Thus Ken continues to describe it as “awesome,” while Roberta still names it as her favorite of all the games she made. It was all too easy in 1995 to believe that Phantasmagoria really was the future of gaming writ large.

The Oakhurst folks finished three other adventure games that year, with more mixed commercial results. Space Quest 6, which was made with a lot of the traditional Sierra style but without a lot of enthusiasm from upper management, validated the latter’s skepticism when it failed to sell all that well, signifying the end of that series. Torin’s Passage, a workmanlike fantasy adventure in the King’s Quest mold by Al Lowe of Leisure Suit Larry fame, was another mediocre performer, one whose reason for existing at all at this juncture was a little hard to determine. Finally, the second of the new generation of Sierra adventures, built like Phantasmagoria around filmed actors, was The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery. I’ll return to it in my next article.

Yet Oakhurst was no longer the be all, end all of Sierra. In the new corporate order envisioned by Ken Williams and Mike Brochu, the adventure games that came out of Oakhurst were to be only a single piece of the overall Sierra puzzle. They planned to build an empire from Bellevue that would cover all of the bases in consumer-oriented software. Already over the course of the previous half-decade, Sierra had acquired the Oregon-based jack-of-all-trades games studio Dynamix, the Delaware-based educational-software specialist Bright Star, and the artsy French games studio Coktel Vision. Now, in the first year after Brochu’s hiring, they made no fewer than six more significant acquisitions: the Texas-based Arion Software, maker of the recipe-tracking package MasterCook; the Washington-based Green Thumb Software, maker of Land Designer and other tools for gardeners; the British Impressions Software, maker of a diverse lineup of strategy games; the Massachusetts-based Papyrus Design Group, a specialist in auto-racing simulations; the Washington-based Pixellite Group, the maker of Print Artist, a software package for creating signs and banners; and the Utah-based Headgate Studios, a specialist in golf simulations.

Of all the other products Sierra released in 1995, the one that came closest to matching Phantasmagoria‘s success came from good old reliable Dynamix. “I was in a high-level meeting,” remembers Dynamix’s founder Jeff Tunnell, “and the sales manager for all of Sierra said, ‘These fishing games are selling in Japan on the Nintendo.’ Everybody started laughing. But I said, ‘I’ll do one.'” Like Phantasmagoria, Trophy Bass was consciously designed for a different demographic than the typical computer game; it looked more at home on the shelves of Walmart than Electronics Boutique or Software Etc. It shocked everybody by outselling all other Sierra games in 1995, with the exception only of Roberta Williams’s big adventure, becoming in the process the best-selling game that Dynamix ever had or ever would make. Thanks to it, the later 1990s would see a flood of other fishing and hunting games, most of them executed with less love than Trophy Bass. Hardcore computer gamers scoffed at these simplistic knockoff titles and the supposed simple-minded rednecks who played them, but they sold and sold and sold.

Along with Phantasmagoria and other Sierra products like The Incredible Machine, Trophy Bass provided proof positive that there were any number of new customer bases out there just waiting to be tapped, made up of people who were looking for something a bit less demanding of their time and energy than the typical computer game for the hardcore, with themes other than the nerdy staples of science fiction, fantasy, and military simulations. Whatever his faults and mistakes — you know, those ones which I haven’t hesitated to describe at copious length in these articles — Ken Williams realized earlier than most that these people were out there, and never stopped trying to reach them, even as he also navigated the computer-game market as it was currently constituted. For this, he deserves enormous credit.

As Sierra came out of 1995, he had good reason to feel pleased with himself. Revenues had nearly doubled over those of the previous year, to $158.1 million, and even all of the acquisitions couldn’t prevent the company from clearing over $16 million in profits. With Electronic Arts, the only publisher of consumer software with equal size and clout, now investing more and more heavily in console games, Sierra seemed to stand on the verge of complete dominance of the exploding marketplace for home-computer software. Ken’s longstanding dream of selling software to everyone was so close to fruition that he could taste it. And as for Roberta: her own dream of becoming the Steven Spielberg of interactivity seemed less and less far-fetched each day.

If you had told the pair that Roberta would never get the chance to make another point-and-click adventure game, or that the Oakhurst sound stage would be written off as a colossal blind alley and decommissioned within the next few years, or that neither of them would still be working for Sierra by that point, or that Sierra’s Oakhurst branch as a whole would be shuttered well before the millennium… well, they would presumably have been surprised, to say the least.

(Sources: the books Phantasmagoria: The Official Player’s Guide by Lorelei Shannon and Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line by Ken Williams, Computer Gaming World of February 1995 and November 1995, Los Angeles Times of November 14 1995, Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of Fall 1994, Holiday 1994, Spring 1995, and Holiday 1995; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Video sources include a vintage making-of-Phantasmagoria video and Matt Chat 201. Other online sources include “How Sierra was Captured, Then Killed, by a Massive Accounting Fraud” by Duncan Fyfe at Vice, Sierra’s SEC filing for 1996, Anthony Larme’s Phantasmagoria fan site, the Adventure Classic Gaming interview with Roberta Williams, Ken Williams’s comments in a Sierra Gamers discussion of King’s Quest opening movies, and the current MasterCook website. And my thanks go to Corey Cole, who took the time to answer some questions about this period of Sierra’s history from his perspective as a developer there.)