And so at last, twelve years after a group of MIT hackers had started working on a game to best Crowther and Woods’s original Adventure, it all came down to Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur, Infocom’s 35th and final work of interactive fiction. Somewhat ironically, this era-ending game wasn’t written by one of Infocom’s own long-serving Imps, but rather by the relatively fresh and inexperienced Bob Bates and his company Challenge, Incorporated, for whom Arthur represented only their second game. On the other hand, though, Bates and Challenge did already have some experience with era-ending games. Their previous effort, Sherlock: The Riddle of the Crown Jewels, had been the last text-only Infocom game to be published. As Bates’s buddy Steve Meretzky delights in saying, it’s lucky that Challenge would never get the chance to make a third game. What with them having already “single-handedly killed” the all-text Infocom game with Sherlock and then Infocom as a whole with Arthur, a third Challenge game “probably would have killed the entire computer-game industry.” We kid, Bob, we kid.

The story of Arthur‘s birth is the story of one of the few things to go according to plan through the chaos of Infocom’s final couple of years. When he’d first pitched the idea of Challenge becoming Infocom’s first outside developer back in 1986, Bates had sealed the deal with his plan for his first three games: a Sherlock Holmes game, a King Arthur game, and a Robin Hood game, in that order. Each was a universally recognizable character from fiction or myth who also had the advantage of being out of copyright. The games would amount to licensed works — always music to corporate parent Mediagenic’s [1]Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. ears — which didn’t require that anyone actually, you know, negotiate or pay for a license. It seemed truly the best of both worlds. And indeed, after Bates finished the Sherlock Holmes game, to very good creative if somewhat more mixed commercial results, his original plan still seemed strong enough that he was allowed to proceed to phase two and do his King Arthur game.

He chose to make his game the superhero origin story, if you will, of the once and future king: his boyhood trials leading up to his pulling the sword Excalibur from the stone in which it’s been embedded, thereby proving himself the rightful king of England. That last act would, naturally, constitute the climax of the game. In confining himself to the very beginning of the story of King Arthur, Bates left open the possibility for sequels should the game be successful — another move calculated to warm hearts inside Mediagenic’s offices, whose emerging business model in the wake of the Bruce Davis takeover revolved largely around sequels and licenses.

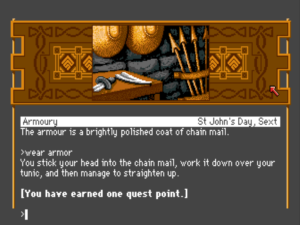

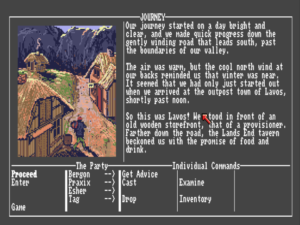

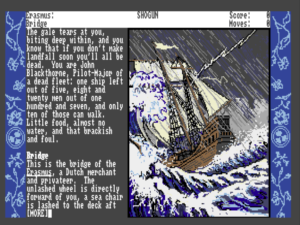

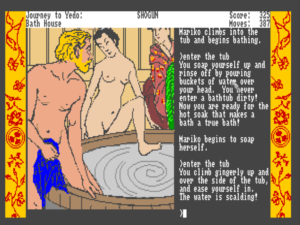

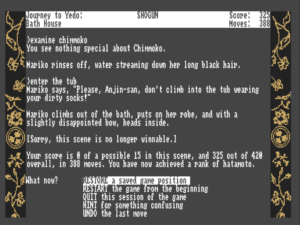

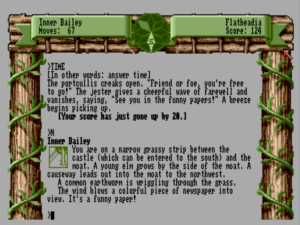

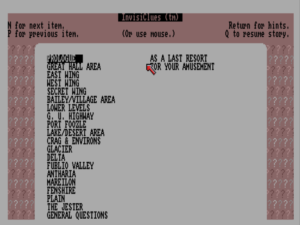

From the perspective of Challenge, Arthur was created the same way as had been Sherlock, from their offices in suburban Virginia as an all-text game, using a cloned version of Infocom’s DEC-hosted development environment that ran on their own local DEC minicomputer. But after Challenge had delivered their game to Infocom this time around, it went through a lengthy post-production period in the latter’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, offices, during which it was moved to Infocom’s new Macintosh-hosted development environment, then married to graphics created by a team of artists. Due at least to some extent to the nature of its development process, Arthur can be seen as a less ambitious game than any of the three works of graphical interactive fiction that preceded it. Its pictures were used only as ultimately superfluous eye candy, static illustrations of each location without even the innovative scrolling page design of Shogun. A few niceties like an onscreen map and an in-game hint menu aside, this was graphical interactive fiction as companies like Level 9 and Magnetic Scrolls had been doing it for years, the graphics plainly secondary to the very traditional text adventure at the game’s core.

Created by a team of several outside contractors, Arthur‘s pictures are perhaps best described as “workmanlike” in comparison to the lusher graphics of Shogun and especially Journey.

Far from faulting Arthur for its lack of ambition, many fans then as well as now saw the game’s traditionalism as something of a relief after the overambitious and/or commercially compromised games that had preceded it. Infocom knew very well how to make this sort of game, the very sort on which they’d built their reputation. Doubtless for that reason, Arthur acquits itself quite well in comparison to its immediate predecessors. It’s certainly far more playable than any of Infocom’s other muddled final efforts, lacking any of their various ruinous failings or, for that matter, any truly ruinous failings of its own.

That said, the critical verdict becomes less positive as soon as we widen the field of competition to include Infocom’s catalog as a whole. In comparison to many of the games Infocom had been making just a couple of years prior to Arthur, the latter has an awful lot of niggling failings, enough so that in the final judgment it qualifies at best only as one of their more middling efforts.

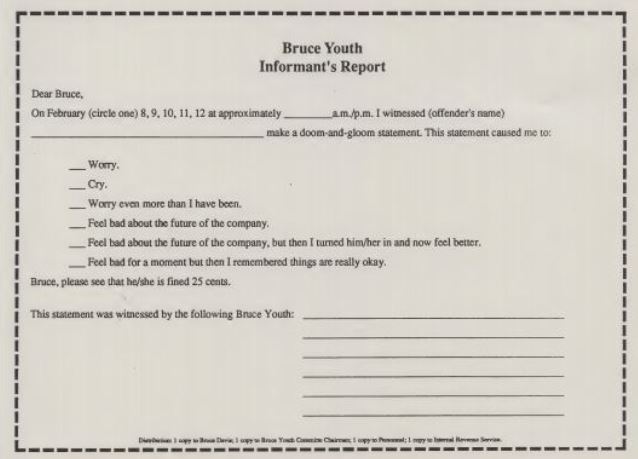

A certain cognitive dissonance is woven through every aspect of Arthur. In his detailed and thoughtful designer’s notes for the game, which are sadly hidden inside the hint menu where many conscientious players likely never realized they existed, Bates notes that “there is an inherent conflict built into writing a game about King Arthur. It is the conflict between history and legend — the way things were versus the way we wish they were.” Bates took the unusual course of “cleaving to the true Arthur,” the king of post-Roman Britain who may have reigned between 454 and 470, when the island was already sliding into the long Dark Ages. He modeled the town in which the game is set on the ancient Roman British settlement of Portchester, just northwest of Portsmouth, which by the time of the historical Arthur would likely have been a jumble of new dwellings made out of timber and thatch built in the shadow of the decaying stonework left behind by the Romans. A shabby environment fitting just this description, then, becomes the scene of the game. Bates invested considerable research into making the lovely Book of Hours included with the game as reflective of the real monastical divine office of the period as possible. And he even wrote some snippets of poetry in the Old English style, based on alliteration rather than rhyme. I must say that this approach strikes me as somewhat problematic on its face. It seems to me that very few people pick up an Arthurian adventure game dreaming of reenacting the life and times of a grubby Dark Ages warlord; they want crenelated castles and pomp and pageantry, jousts and chivalry and courtly love.

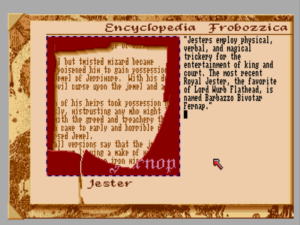

But far more problematically, having made his decision, Bates then failed to stick to it. For instance, he decided that jousting, first anachronistically imposed upon the real Arthur many centuries after his death, had to be in his own more historically conscientious version of the story “to make the game more enjoyable.” The central mechanic to much of the gameplay, that of being able to turn yourself into various animals, is lifted from a twentieth-century work, T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone, as is the game’s characterization of Arthur as a put-upon boy. Other anachronisms have more to do with Monty Python than written literature, like the village idiot who sings about his “schizophrenia” and the kraken who says he “floats like a butterfly, stings like a bee.” I should say that I don’t object to such a pastiche on principle. Writers who play in the world of King Arthur have always, as Bates himself puts it, “projected then-current styles, fashions, and culture backwards across the centuries and fastened them to Arthur.” Far from being objectionable, this is the sign of a myth that truly lives, that has relevance down through the ages; it’s exactly what great writers from Geoffrey of Monmouth to Thomas Malory, T.H. White to Mary Stewart have always done. The myth of King Arthur will always be far more compelling than the historical reality, whatever it may be. What I object to is the way that Bates gums up the works by blending his pseudo-historical approach with the grander traditions of myth and fiction. The contrast between the Arthur of history and the Arthur of imagination makes the game feel like a community-theater production that spent all its money on a few good props — for instance, for the jousts — and can’t afford a proper stage. Far from feeling faithful to history, the shabby timber-and-thatch environs of his would-be Portchester just feel low-rent.

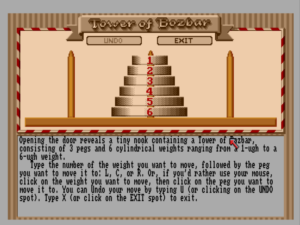

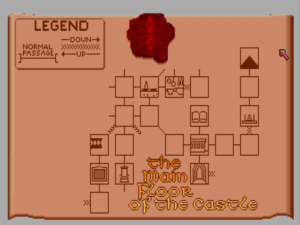

A similar cognitive dissonance afflicts the game and puzzle design. In some ways, Arthur is very progressive, as feels appropriate for the very last Infocom text adventure, presumably the culmination of everything they’d learned. For the first time here, the hint menu is context-sensitive, opening up new categories of questions only after you encounter those puzzles for the first time. (It’s also integrated into the structure of the story in a very clever way, taking the form of Merlin’s future-scrying crystal ball.) The auto-map is useful if not quite as useful as Infocom’s marketing might have liked it to be, and for the first time here the new parser, rewritten from the ground up for this final run of graphical games, does sometimes evince a practical qualitative difference from the old. In these respects and others, Arthur represents the state of the art in text adventures as of 1989.

In other ways, however, Arthur is profoundly old-school, not to say regressive. There is, for instance, an unadulteratedly traditional maze in here, the first such seen in an Infocom game since Zork I‘s “maze of twisty little passages, all alike.” There is a trick to figure out at the beginning of the one in Arthur — the old drop ‘n’ plot isn’t possible, necessitating the finding of another method for distinguishing one room from another — but after that moment of inspiration you can look forward to the tedious perspiration of plotting out ten rooms and the hundred separate connections that bind them. How odd to think that the only Infocom games to include traditional mazes were their very first and their very last. And while we’re on the subject of Zork I, I should mention that there’s a thief character of sorts in Arthur who’s every bit as annoying as his shifty progenitor. When you first wander innocently into his domain, he steals all your stuff with no warning. (Thankfully, undo is among the game’s modern conveniences.) But perhaps the best illustration of Arthur‘s weird mixing of new- and old-school is the magic bag you find in Merlin’s cave. It can hold an infinite amount of stuff, thus relieving you of the object-juggling so endemic to so many early text adventures from Infocom and others. Unfortunately, though, the bag is stuck behind the domain of the aforementioned thief, who steals it as soon as you try to walk out with it. Thus this huge convenience is kept out of your hands for what may for many players — Arthur is quite nonlinear — amount to the bulk of the game. Progression and regression, all in one would-be handy bag of holding.

In marrying its puzzles to its plot, Arthur is once again best described as confused. Instead of a single score, Arthur has four separate tallies, measuring how “wise and chivalrous,” “strong and courageous” you’ve so far become. In common with a number of late Infocom games, there’s a slight CRPG element at play here: your scores actually affect your ability to perform certain actions. The goal, naturally, is to “gain the experience you need to claim the sword,” in the course of which you “must demonstrate them [your knightly virtues] for all to see.” So, when it comes down to the final climactic duel with King Lot, the villain of the game, what do you do? You distract him and sucker-punch him, that’s what. How’s that for chivalry?

Before wrapping up my litany of complaints, I do have to also mention a low-level bugginess that’s not awful by the standards of the industry at large but is quite surprising to find in an Infocom game. The bugs seem to largely fall into the category of glitches rather than showstoppers: if you immediately wear some armor you’ve just discovered instead of picking it up first and then wearing it, you don’t get the points you’re supposed to; another character who normally won’t follow you into a certain location will suddenly do so if you lead him in animal form, which allows you to bypass a puzzle; etc. Relatively minor as such glitches may appear on their face, Arthur‘s CRPG-like qualities make them potentially deadly nevertheless. Because your success at certain necessary actions is dependent on your score, the points you fail to earn thanks to the bugs could make victory impossible.

Scorpia, Computer Gaming World‘s influential adventure-game columnist, called Arthur nothing less than “Infocom’s most poorly produced game ever,” labeling the disk-swapping required by the Apple II version “simply outrageous”: “When you have to change disks because part of a paragraph is on one, and the rest on another, you know something is wrong with the design. This is also sometimes necessary within a single sentence.” These problems made the much-vaunted auto-map feature essentially unusable on the Apple II, requiring as that version did a disk swap almost every time you wanted to take a peek at the map. Granted, the Apple II was by this point the weak sister among the machines Infocom continued to support, the only remaining 8-bit in the stable — but still, it’s hard to imagine the Infocom of two or three years before allowing an experience as unpolished as this into the wild on any platform.

During Arthur‘s lengthy post-production period, Bates already turned his mind to his next project. It was here that that surprisingly durable original plan of his finally fell victim to the chaos and uncertainty surrounding Infocom in these final months. Still searching desperately for that magic bullet that would yield a hit, Infocom and Mediagenic decided they didn’t feel all that confident after all that the Robin Hood game would provide it. Bates delivered a number of alternative proposals, including a sequel to Leather Goddesses of Phobos and a game based on The Wizard of Oz — yet another licensed game that wouldn’t actually require a license thanks to an expired copyright. Most intriguingly, or at least amusingly, he proposed a mash-up of the two ideas, a Wizard of Oz with “more suggestive language, racier insinuations, and a sub-stratum of sex running throughout. We could substitute a whip for the striped socks and dress Dorothy in leather.” History doesn’t record what Mediagenic’s executives said to that transgressive idea.

In the end, Bates had his next project chosen for him. In a development they trumpeted in inter-office memoranda as a major coup, Mediagenic had secured the rights to The Abyss, the upcoming summer blockbuster from James Cameron of Terminator and Aliens fame. This time Bates drew the short straw for this latest Mediagenic-imposed project that no one at Infocom particularly wanted to do. He was provided with a top-secret signed and numbered copy of the shooting script, and dispatched to Gaffney, South Carolina, where filming for the underwater action-epic was taking place inside the reactor-containment vessel of a nuclear power plant which had been abandoned midway through its construction. After meeting briefly there with Cameron himself, he returned to Virginia to purchase an expensive set of Macintosh IIs through which to clone Infocom’s latest development system. (With Infocom’s DEC system being decommissioned and sent to the scrapyard at the end of 1988, he now didn’t have any other choice but to adapt Challenge’s own technology to the changing times.) The beginning of the Abyss game he started on his new machines, a bare stub of a thing with no graphics and little gameplay, would later escape into the wild; it’s been passed around among fans for many years.

But events which I’ll document in my next article would ensure that the interactive Abyss would never become more than a stub and that the money spent on all that new equipment would be wasted. Bob Bates’s Infocom legacy would be limited to just two games, the first a very satisfying play, the second a little less so. Lest we be tempted to judge him too harshly for Arthur‘s various infelicities, we should note again that the three most prolific Imps of all — Steve Meretzky, Dave Lebling, and Marc Blank — had all delivered designs that failed far more comprehensively in the months immediately preceding the release of Bates’s effort, Infocom as a whole’s last gasp, in June of 1989. By the time of its release, Arthur was already a lame duck; the Infocom we’ve come to know through the past four and a half years worth of articles on this blog was in the final stages of official dissolution. With its anticlimactic release having been more a product of institutional inertia than any real enthusiasm for the game on Mediagenic’s part, Arthur‘s sales barely registered.

So, it remains for us only to tell how the final curtain (shroud?) came to be drawn over the short, happy, inspiring, infuriating life of Infocom. And, perhaps more importantly, we should also take one final glance back, to ask ourselves what we know, what we’ve recently learned, and what will always remain in the realm of speculation when it comes to this most beloved, influential, and unique of 1980s game-makers. We’ll endeavor to do all that next time, when we’ll visit Infocom for the last time.

(Sources: As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Some of it is also drawn from Jason’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents. Plus the September 1989 issue of Computer Gaming World, and the very last issue of Infocom’s The Status Line newsletter, from Spring 1989. And my huge thanks go out to Bob Bates, who granted me an extended interview about his work with Infocom.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. |

|---|