Amidst so much else, the 1990s saw the rise and fall of the narrative-driven space sim. The sub-genre was effectively invented in 1990, when Wing Commander dared to add a set-piece story line to the sturdy foundation of the more open-ended British classic Elite. It reached a peak of commercial and critical acceptance in 1994 with Wing Commander III and TIE Fighter, only to fall off the big publishers’ radar completely by shortly after the turn of the millennium. As you regular readers know, I’ve been writing the final installments to a lot of stories recently, a symptom of the period of churn and consolidation in which these histories currently find themselves. Now I’m on the verge of writing my last words on not just a company but a whole category of games as a mainstream commercial force — almost, I’m tempted to say, a whole subculture of gaming, one of the oddest of them all when you stop to think about it.

Even the phrase “space sim” is kind of strange and misleading. What were these games supposed to be simulating? Definitely not any form of real spaceflight — not when they chose to implement atmospheric drag, meaning that your ship slows down if you let off the throttle in exactly the way that a real vehicle out in the vacuum of space doesn’t. Their developers started with the way space combat was presented in the Star Wars films, which had themselves happily ignored everything we know about the nature of real space travel in favor of dogfights borrowed from old Second World War movies. Then they just piled on whatever seemed fun and interesting to them, which often entailed delving deeper into the same wellspring as George Lucas. (It was no coincidence that Lawrence Holland, one of the foremost practitioners of the space sim, cut his teeth as a game developer on World War II flight simulators.) Space sims were known by that name because of their vibe alone — because they subjectively felt like simulators, no matter how divorced they were from the reality of space travel. (There are lessons to be drawn from this, if we choose to heed them. The fact is that almost every game which is labelled a simulator is less of one than it purports to be. This is worth remembering any time anyone encourages you to take any game too seriously as a reflection of the real world.)

Chris Roberts’s Wing Commander games made the space-sim formula still more uncanny, by interleaving the missions in space with potboiler relationship drama. It may have been weird on the face of it, seemingly more a product of some random butterfly somewhere flapping its wings than anything flown in on the wings of fate, but for the better part of a decade quite a lot of people loved it.

And then they didn’t so much anymore…

Being an inveterate hiker when I’m not sitting behind a computer, I can tell you that it’s sometimes harder than you think it ought to be to realize when you’ve reached peak elevation in a landscape. The same is true in the landscape of media. As I noted above, the space sim reached its peak already in 1994, even though it would take a few years for everyone to cotton onto that fact. For this was the year that both the Wing Commander series and LucasArts’s Star Wars space sims, the eternal yin and yang of the sub-genre, released their best-remembered installments.

Wing Commander III: Heart of the Tiger doubled down on creator Chris Roberts’s passion for the cinematic side of the experience by interleaving a fairly workmanlike space-combat game with a semi-interactive movie that featured digitized human actors, among them such established Hollywood talents as Jason Bernard, Malcolm McDowell, John Rhys-Davies, and Tom Wilson. In what was arguably the greatest feat of stunt casting in the history of games, the star of the show was none other than Mark Hamill. Over a decade after he had last portrayed Luke Skywalker on the big screen, he portrayed here another space-fighter jock, the player’s own avatar, Colonel Christopher Blair. The presence of so many recognizable actors garnered Wing Commander III considerable attention in the glossy mainstream press. The “Siliwood” dream of Northern and Southern California joining forces to forge a new form of entertainment was nearing its frenzied peak in tandem with the space sim in 1994. Wing Commander III was widely hailed, notwithstanding its computer-generated sets and general B-movie aesthetics, as a proof of concept for the better, richer interactive movies that were still to come. Hyped inside the industry as the most expensive game yet made, it garnered a rare five-stars-out-of-five review from Computer Gaming World, and sold at least half a million copies in the United States alone, at an average street price of about $70.

If Wing Commander III was trying to capitalize on gamers’ love for Star Wars in some less-than-subtle ways, LucasArts’s TIE Fighter had the advantage of literally being Star Wars, coming out of George Lucas’s very own games studio. It also had the advantage of being a much better, deeper game where it really counted, eschewing digitized actors and soapy relationship drama to focus firmly on the action in the cockpit. It too was given a perfect score by Computer Gaming World, and sold in similar numbers to Wing Commander III, albeit without attracting the same level of attention from the mainstream press.

Alas, it was mostly downhill for the two franchises from there; such is rather the nature of peaks, isn’t it? In early 1996, barely eighteen months after Wing Commander III, Chris Roberts and his employer Origin Systems were ready with Wing Commander IV: The Price of Freedom. Despite the short turnaround time, it represented another dramatic escalation in budget and ambition on the cinematic side of the equation. (The combat engine, with which Roberts by now hardly bothered to concern himself, was largely unchanged.) Mark Hamill and most of the rest of the previous cast were back, for a production that was shot on film this time rather than videotape, on real sets rather than in front of green screens that were filled in with computer-generated backgrounds after the fact. Yet many gamers found the end results to be paradoxically less stunning. The filmed sequences of Wing Commander IV fell into a sort of uncanny valley, being no longer clearly part of a computer game and yet having nowhere near the production values of even the most modest Hollywood features of the standard stripe. Probably more importantly, the Siliwood cultural moment was quickly passing, leaving the game with something of the odor of an anachronism. The mainstream was becoming more interested in the burgeoning World Wide Web than the wonders of multimedia and CD-ROM, even as hardcore gamers were embracing the non-stop action of the first-person-shooter and real-time-strategy genres, having lost patience with the long cutscenes and endless exposition of interactive movies.

For a cost of more than three times that of Wing Commander III, Wing Commander IV sold a third as many copies. Origin’s management told Chris Roberts that any future games in the series would have to scale back the movie angle and try harder to refresh the increasingly stale gameplay. By way of a response, Roberts quit his job at Origin.

From here, the decline was steep for Wing Commander. In September of 1996, the USA television network debuted Wing Commander Academy, a Saturday-morning cartoon featuring the voices of Mark Hamill, Malcolm McDowell, and Tom Wilson among other actors from the last couple of games. All of the parties involved had envisioned the show capitalizing on a hit game. Absent said hit, it disappeared from the airwaves after just thirteen episodes.

The franchise’s last hurrah as a game came with Wing Commander: Prophecy, which appeared at the end of 1997. “Wing Commander III and IV were both great products,” said Prophecy’s producer Adam Foshko, straining hard to be diplomatic toward his predecessor Chris Roberts, “but they are more like unequal halves. This is a much more synergistic product. It’s very team-driven. It’s not one person’s vision, and I think it shows.” At its best, Prophecy really did play better than any Wing Commander in years, evincing the far greater level of attention the team paid to the action in the cockpit. Less positively, the movie sequences were cheesier and more constrained, even as a plan to bring the game fully in line with the hardcore set’s current priorities by adding a multiplayer component ultimately came to naught. When Prophecy didn’t sell well, that was that for Wing Commander as a gaming franchise. The commercial prospects of an expansion pack that the team had been working on — a return to the old “mission disks” that had made Origin a bundle back before the former Luke Skywalker and his Hollywood friends had entered the picture — looked so dire that Origin just dumped the whole thing onto the Internet for free.

Meanwhile Lawrence Holland and his colleagues had been going through some travails of their own. After making a well-received TIE Fighter expansion pack and a “Collector’s CD-ROM” with yet more new missions to fly, Holland left LucasArts on amicable terms to start a studio called Totally Games, taking his technology and most of his team with him. From the average fan’s perspective, this was a distinction without a difference: Totally’s games would still be Star Wars space sims, and they would still be published by LucasArts.

Like their counterparts at Origin, the folks at Totally could totally see the potential in offering a multiplayer mode to keep up with the changing times. But unlike them, they stuck with the program. In fact, the next iteration of their series was designed to be multiplayer first and foremost. Holland and his people spent almost two years finding ways to make multiplayer work reliably despite all of the challenges of the high-latency, dial-up Internet of the era.

The result of those efforts landed with a resounding thud in the spring of 1997, becoming a case study in the dangers of failing to understand your customers. Holland’s X-Wing and TIE Fighter games may not have been interactive movies in the sense of Wing Commander III and IV, but people had nevertheless loved their unfolding campaigns, loved the sense of playing a part in what could easily have been a novel set in the Star Wars Expanded Universe. The ingeniously titled X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter didn’t give them any of that; its single-player mode was little more than a place to practice for multiplayer matches. “The sad part is, I was really looking forward to this game,” wrote Computer Gaming World’s reviewer, echoing the sentiments of thousands upon thousands of deeply disappointed ordinary players. “After the high of TIE Fighter, I wanted another Star Wars experience that would be just as immersive and fun. And while my wish for multiplayer Star Wars action was fulfilled, my hope for an equivalent single-player experience wasn’t.” In a last-ditch attempt to save their baby, Totally put together an expansion pack whose sole purpose was to provide a single-player campaign of the old style. It did so competently enough, but inspired it was not, and it never had much chance of rescuing a base game that was already a fixture of bargain bins by the time the expansion appeared in January of 1998.

In contrast to Wing Commander, however, LucasArts and Totally’s space-sim series was afforded one more kick at the can after 1998. To hear Lawrence Holland talk about it when it was still in development, Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance was the be-all, end-all in space sims. For those who wanted a story-driven campaign, this game’s would be the biggest and best ever. For those who wanted multiplayer action, this game’s multiplayer mode would be more stable and convenient than that of X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter. For those who cared about graphics, this game’s would be the best yet, taking full advantage of the 3D-accelerator cards that were proliferating everywhere. It was an ambitious plan, especially considering that this old-school Star Wars game had to be finished before The Phantom Menace, the first new Star Wars movie in more than a decade and a half, reached theaters in May of 1999, bringing with it an onslaught of next-generation toys and games.

X-Wing Alliance met that goal, being released in March of 1999. The most remarkable thing about it is how many of its other lofty goals it managed to achieve against the strictures of time and budget. The story is almost Wing Commander-like in its elaborateness, presenting for the first time a named, strongly characterized protagonist, a youthful member of a trading family caught between the Rebel Alliance and the Empire. His story is told not only through the usual mission briefings but also through emails and radio chatter full of enough interpersonal drama to warm the cockles of Chris Roberts’s heart. The campaign begins on the ice-planet Hoth, is interwoven with the events of The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, and climaxes with you getting to fly the Millennium Falcon at the Battle of Endor. What dedicated Stars Wars fan could resist?

Sadly, further examination of X-Wing Alliance reveals some significant shortcomings. The individual missions are often unpolished, sometimes failing to even convey adequately what their goals are; trying to complete some of them feels like trying to read the designers’ minds. Ironically, this is the same general set of issues that dragged down the original X-Wing, upon which TIE Fighter did such a magnificent job of improving. It’s disheartening to see them making a return at this late date. Like so many flawed games, X-Wing Alliance might have been amazing if it had just been allowed a few more months in the oven.

That said, the biggest obstacle that X-Wing Alliance faced in the marketplace was probably just the tenor of the times. As I already noted, at a time when everyone was excited and optimistic about The Phantom Menace, the new face of Star Wars, this game was old-school. And yet that was only the beginning of the commercial headwinds it faced. Gamers in general were turning away from simulations in droves; real-world flight and combat simulators too, which had in some earlier years accounted for more than 20 percent of the computer-game industry’s total revenues, had now fallen markedly out of favor. Fewer and fewer gamers even owned joysticks anymore. (To what extent this was a cause and to what extent it was a symptom of simulators’ declining fortunes is a matter of debate.) Existing fans and would-be fans of simulations were being tempted away by other action-packed genres that were quicker and easier to pick up and play for the first time, while still offering plenty of long-term rewards for those who stuck with them. It seemed that fewer people had the patience for games that started by asking you to read a thick manual, then required you to go through a veritable digital flight school before you could start playing them for real.

At any rate, by Y2K both Wing Commander and the Star Wars space sims had been consigned by their publishers to the dustbin of history. Other titles in development that had dreamed of competing with the space sim’s dynamic duo head-on suffered the same fate. The most high-profile of the cancellations was a space sim from Sierra that took place in the universe of the recently concluded Babylon 5 television series. Created with heavy input from Christy Marx, a Babylon 5 scriptwriter who had earlier designed a couple of point-and-click adventure games for Sierra, it was supposed to “tart up a tired genre” and “radically change the face of gaming” with “non-linear, non-branching storytelling, a brilliant modular refit job on nearly five hours of [television composer] Christopher Franke’s music, plus an attention to the physics of space travel that will raise the high bar on space-combat games for years to come.” It got to within a few months of completion, got as far as having the box art prepared before falling victim in late 1999 to an uncongenial marketplace and to the chaos inside Sierra that had followed that venerable mom-and-pop company’s purchase by two separate corporate conglomerates in a period of just a few years.

Still, the space-sim diehards did get one last pair of classics from an utterly unexpected source before their favored sub-genre disappeared from the catalogs of the big publishers forever. In fact, many a grizzled joystick jockey will tell you even today that the second of the two Freespace games is the best of its type ever created — yes, better even than the hallowed TIE Fighter.

The first mover without whom Freespace would never have come to be was a native Chicagoan named Mike Kulas, whose early gigs as a game programmer included stints at subLogic of Flight Simulator fame and at Lerner Research, a precursor to the legendary Looking Glass Studios. At the latter workplace, he befriended one Matt Toschlog. “If this is what it means to run a company, we can do it too,” the friends decided after spending two years at the dawn of the 1990s on an ultimately unsatisfying racing game that was sold in the trade dress of Car and Driver magazine. “What’s the worst that could happen? It’ll fail and we’ll have to go back to work for somebody else.” Kulas and Toschlog moved out of the Boston area and back to Champaign, Illinois, also the home of subLogic. Champaign seemed a good place to open a new studio: it had the advantages of fairly cheap rents and a large pool of enthusiastic young tech talent, thanks to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the source of such innovations as the pioneering PLATO system of the 1970s and the point-and-click Mosaic browser that was popularizing the nascent World Wide Web at that very moment.

Kulas and Toschlog founded Parallax Software in June of 1993, six months before DOOM ignited a craze for immersive 3D action that would remake much of the industry in its image over the next few years. Luckily, Parallax was well-equipped to capitalize on the trend, what with the founders’ experience with 3D graphics and the passionate young sparks they were able to recruit from the nearby university. Descent, their very first game, put you behind the controls of a small flying vehicle and set you loose inside a series of 3D-rendered outer-space mining complexes, filled with robots gone haywire. It was different enough to stand out in a sea of DOOM clones, yet felt very much in step with the times in a broader sense. Upon its release in March of 1995, Descent became a surprise hit for its publisher Interplay, whose marketers were left scrambling to catch up to the buzz on the street with a port to the Sony PlayStation and television campaigns starring mid-tier celebrities. Made for less than half a million dollars, the game was one heck of a debut for Parallax. It and its almost-as-successful 1996 sequel were enough to make them think that winning fame and fortune in the games industry was actually pretty easy.

Matt Toschlog had never been happy in Champaign. Flush with all of that Descent cash, he wanted to move Parallax somewhere else. Mike Kulas, on the other hand, preferred to stay put. Unable to find any other way out of the impasse, the founders agreed to split the company between them. In late 1996, Toschlog moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to start Outrage Entertainment. Kulas decided to rename his half of the company Volition — “an intense act of will to accomplish something” — after stumbling across the word in a book. Outrage’s first project was to be the inevitable Descent3; Volition’s was to be Freespace, a space sim that would, as its name implied, take the player out of the asteroid mines and into the limitless inky-black freedom that lay beyond.

Freespace isn’t shy about displaying its influences. Created by a bunch of guys who adored LucasArts’s X-Wing and TIE Fighter sims, it hews unabashedly to their template. After the requisite flight training, you’re tossed into an interstellar war between your Terran Alliance and an alien race known as the Vasudans. Then another group of aliens shows up, a shadowy enigma that comes to be called the Shivans, who are so powerful that the old antipathies are quickly forgotten, and Terrans and Vasudans unite to face the greatest threat either of their races has ever known.

Although neither its core gameplay model nor its fiction is remotely revolutionary, Freespace stands out for how well it executes on this derivative material. The graphics are exceptional for their era, the possibility space behind the controls expansive, the mission design uniformly solid. Inspiration in game design is wonderful, but we should never forget the value of perspiration. The people who made Freespace loved what they were doing enough to sweat every small detail, and it shows. The only place where the game fell down a bit back in the day was a somewhat under-baked multiplayer mode.

Interplay insisted on calling the game Descent: Freespace (“From the creators of Descent!”) in the hope of riding the coattails of the publisher’s biggest hit in recent memory. Whatever else you can say about it, it certainly wasn’t their worst exercise in Descent branding. (That would be Descent to Undermountain, an ill-advised attempt to use the old Parallax engine for, of all things, a Dungeons & Dragons-licensed CRPG.) And who knows? Maybe the branding even did some good. Upon its release in June of 1998, Freespace sold well enough to be modestly profitable for its studio and publisher and convince Interplay to fund an expansion pack and a sequel. The only catches were that Volition had to turn both out quickly, without spending too much money on them.

The expansion pack, which they called Silent Threat, ended up being short and perfunctory, the definition of inessential. The full-fledged sequel, however, was a minor miracle. It defied every cynical expectation raised by its abbreviated development cycle when it shipped on September 30, 1999.

Freespace 2 — Interplay allowed the cleaner name this time, perhaps to avoid confusion with the recently released Descent3 — did everything its predecessor had done well that much better, then added a finishing touch that it had lacked: a real sense of gravitas, provided largely by the one significant addition to the development team. Jason Scott (not to be confused with the archivist and Infocom documentarian of the same name) was Volition’s first dedicated writer. He made his presence felt with a campaign that was sometimes exhilarating, sometimes harrowing, but always riveting. The outer-space kitty-cats of Wing Commander, even Darth Vader and Emperor Palpatine, paled in comparison to the Shivans after Jason Scott got his hands on them. “The universe is very impersonal,” he says. “Your character is referred to only as ‘Pilot’ or ‘Alpha 1,’ and you’re up against countless waves of a seemingly unbeatable, genocidal adversary that never communicates its goals or motives. In the briefings, we tried to convey the sense of a much larger conflict unfolding in multiple systems, while at the same time hinting that your commanders weren’t telling you the whole story.”

Freespace 2 was never going to single-handedly rescue the space-sim sub-genre, but it did ensure that it went out on a high note. It’s a demanding game even by the usual standards of its kind, one that uses every key on the keyboard and then some, one that is guaranteed to leave you wishing you had more buttons on your joystick, no matter how nerdily baroque it might already be. Some of its more counter-intuitive commands, such as “target my target’s target,” have become memes in certain circles. Yet the developers are unapologetic. “We wanted players to feel like pilots in control of a complex, powerful, responsive, and technologically advanced machine,” says Jason Scott. “Complexity was a virtue.”

I’m almost tempted to write here that this was a shame, in that it put such a high barrier to entry in front of what was actually one of the more sophisticated ludic fictions of its era. My experience with the game probably isn’t unique: I struggled with it for a while, reached a point where I couldn’t seem to hit any enemy that I shot at even as said enemies had become all too good at hitting me, and wound up watching the rest on YouTube, as you do these days. On the other hand, though, why shouldn’t unabashedly demanding games that aren’t quite for me have good writing too?

Because you deserve to hear from someone other than a dabbler like me before we move on, I’m going to take the liberty of quoting Lee Hutchinson, who is a good friend of this site, a stalwart voice of reason in these increasingly unreasonable times of ours through his day job as a senior editor at Ars Technica, and, most importantly for our purposes, a hardcore space-sim junkie in all the ways that I am not. He can explain better than I can what Freespace 2 came to mean to its biggest fans, how it melded gameplay and narrative into an unforgettable roller-coaster ride.

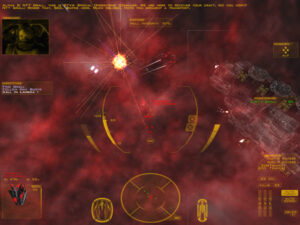

If you’ve seen one of those simplified “evolution of man” charts, showing a chimp-like predecessor far at the left and an upright tool-using human all the way at the right, you’ve got a good idea of how Freespace 2 capped off the genre. It was the culmination of everything that had come before it, and every single gameplay element was refined and polished to a razor-sharp gleam.

Freespace 2 lets players experience a tremendous variety of missions in different fighters with a gamut of capabilities. Each mission is connected by an overarching plot: you may be ambushed while escorting some capital ships in one mission, and then in the next mission you might switch to flying a bomber and be assigned to take those capital ships out. You might be temporarily attached to a special-operations wing flying a prototype starship, or have to fly captured Shivan fighters in a deep-cover mission to scope out an enemy staging point, or deal with total mission failure and objective changes right in the middle of doing dozens of other things. Capital ships fire ridiculously large, ridiculously powerful beam weapons at each other, slicing each other to ribbons and providing a fantastic Babylon 5-esque backdrop while the player duels enemy fighters.

The targeting system is complex and rich; the wingman and escort system is complex and rich; the comms system is complex and rich. Everything about Freespace 2 shows care, love, and craftsmanship — from the chatter going back and forth between your wingmen as you blindly scout a nebula looking for a lost frigate, to the amazingly well-acted mission briefings. In practically every way, it is the Platonic ideal of a space-combat sim.

Starting at about the halfway point, Freespace 2 drops the hammer on the player with a series of tightly linked missions that absolutely do not let up. The war against the Shivans isn’t going well. A faction of Quisling-like humans is trying to defect to the Shivans’ side, taking a large chunk of the human military with it. At several points throughout the long campaign, it feels like the game is about to come to a crashing climax — only it doesn’t end. Things just get worse, and it’s an absolute rush to experience — flying your guts out, desperately trying to fight a rear-guard action against an unknowable enemy that seems to be totally unable to feel remorse, pity, or even fatigue.

I’ve never felt quite the combination of awe, fear, and eagerness I felt as I pushed through to Freespace 2’s endgame. There are lots of gaming experiences I wish I could relive for the first time, but playing Freespace 2 tops the list. That’s as good a way as any to judge a game as the best in its genre.

In the short term at least, Volition wasn’t rewarded very well for creating this game that Lee Hutchinson and more than a few others consider simply the best story-driven space sim ever made, the evolutionary end point of Chris Roberts’s original Wing Commander of 1990. Mike Kulas insists that Freespace 2 didn’t actually lose money for its studio or publisher, but it didn’t earn them much of anything either. Plans for a Freespace 3 were quietly shelved. Thus Freespace 2 came to mark the end of an era, not only for Volition but for computer gaming in general: while not quite the last space sim to be put out by a major publisher, it was the last that would go on to be remembered as a classic of its form.

What with there being no newer games that could compete with it, those who still loved the space sim clung all the tighter to Freespace 2 as the months since its release turned into years. They were incredibly lucky that Volition was staffed by genuinely nice, fair-minded people who felt their pain and were willing to “pay it forward,” as the saying goes. In 2002, Volition uploaded the full source code to Freespace 2 to the Internet for non-commercial use.

They couldn’t possibly have envisioned what followed. As of this writing, 23 years after that act of spontaneous generosity, the Freespace 2 engine has been improved and modernized almost beyond recognition, with support for eye-bleedingly high resolutions and all of the latest fancy graphical effects that my humble retro-gaming computers don’t even support. You can use the updated engine to play Freespace 1 and 2 and the Silent Threat expansion pack, in versions that have been polished to an even shinier gleam than the originals by the hands of hundreds of dedicated volunteers. Even more inspiringly, folks have used the technology to create a welter of new campaigns — effectively whole new space sims that run off what remains the best of all engines for this type of game.

The people who made Freespace 1 and 2 all those years ago are themselves awed by what their pair of discrete boxed computer games have been turned into. Freespace proved to be as much a new beginning as an ending. Long may the space sim fly on in the hands of those who love it most.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: Sierra On-Line’s customer newsletter InterAction of Spring 1999; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of September 20 1996 and February 14 1997; Computer Gaming World of October 1994, February 1995, July 1997, April 1998, October 1998, November 1998, February 1999, July 1999, and January 2000; Retro Gamer 204.

Online sources include interviews with Jack Nichols and Randy Littlejohn on B5 Scrolls, “Growing Up Gaming: The Five Space Sims That Defined My Youth” by Lee Hutchinson at Ars Technica, an interview with some of the core members of the Freespace 2 team by the Space Game Junkie podcast, and a Game Informer documentary about Volition’s history.

Where to Get Them: Wing Commander I and II, Wing Commander III: Heart of the Tiger, Wing Commander IV: The Price of Freedom, Wing Commander: Prophecy, X-Wing, TIE Fighter, X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter, X-Wing Alliance, Descent: Freespace, and Freespace 2 are all available as digital purchases on GOG.com.

I strongly recommend that you run the Freespace games through the Freespace Open engine, even if you’re primarily looking for a retro experience. Both on native Windows 10 and running through WINE on Linux, I found the original Freespace to be subtly broken: I was given only a fraction of the time I ought to have been given to complete the last training mission. (This was not good at all, considering I’m rubbish at the game anyway.) Freespace Open is quite painless to install and maintain using a utility called Knossos. It will walk you through the setup process and then deliver a glitch-free game, whilst letting you select as many or as few modern niceties as you prefer.