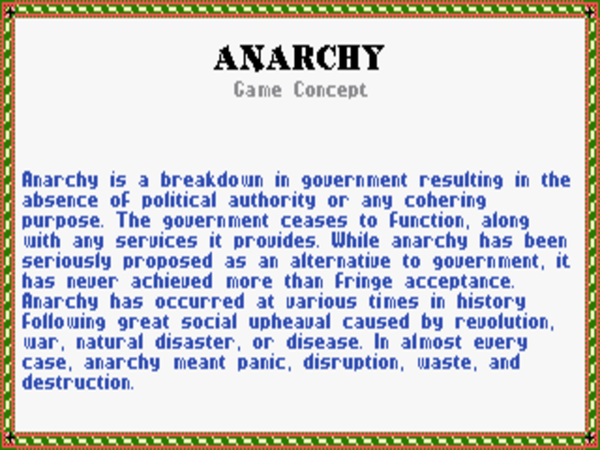

Darklands may well have been the most original single CRPG of the 1990s, but its box art was planted firmly in the tacky CRPG tradition. I’m not sure that anyone in Medieval Germany really looked much like these two…

Throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s, the genres of the adventure game and the CRPG tended to blend together, in magazine columns as well as in the minds of ordinary gamers. I thus considered it an early point of order for this history project to attempt to identify the precise differences between the genres. Rather than addressing typical surface attributes — a CRPG, many a gamer has said over the years, is an adventure game where you also have to kill monsters — I tried to peek under the hood and identify what really makes the two genres tick. At bottom, I decided, the difference was one of design philosophy. The adventure game focuses on set-piece, handcrafted puzzles and other unique interactions, simulating the world that houses them only to the degree that is absolutely necessary. (This latter is especially true of the point-and-click graphic adventures that came to dominate the field after the 1980s; indeed, throughout gaming history, the trend in adventure games has been to become less rather than more ambitious in terms of simulation.) The CRPG, meanwhile, goes in much more for simulation, to a large degree replacing set-piece behaviors with systems of rules which give scope for truly emergent experiences that were never hard-coded into the design.

Another clear difference between the two genres, however, is in the scope of their fictions’ ambitions. Since the earliest days of Crowther and Woods and Scott Adams, adventure games have roamed widely across the spectrum of storytelling; Infocom alone during the 1980s hit on most of the viable modern literary genres, from the obvious (fantasy, science fiction) to the slightly less obvious (mysteries, thrillers) to the downright surprising (romance novels, social satires). CRPGs, on the other hand, have been plowing more or less the same small plot of fictional territory for decades. How many times now have groups of stalwart men and ladies set forth to conquer the evil wizard? While we do get the occasional foray into science fiction — usually awkwardly hammered into a frame of gameplay conventions more naturally suited to heroic fantasy — it’s for the most part been J.R.R. Tolkien and Dungeons & Dragons, over and over and over again.

This seeming lack of adventurousness (excuse the pun!) among CRPG designers raises some interesting questions. Can the simulation-oriented approach only be made to work within a strictly circumscribed subset of possible virtual worlds? Or is the lack of variety in CRPGs down to a simple lack of trying? An affirmative case for the latter question might be made by Origin Systems’s two rather wonderful Worlds of Ultima games of the early 1990s, which retained the game engine from the more traditional fantasy CRPG Ultima VI but moved it into settings inspired by the classic adventure tales of Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells. Sadly, though, Origin’s customers seemed not to know what to make of Ultima games not taking place in a Renaissance Faire world, and both were dismal commercial failures — thus providing CRPG makers with a strong external motivation to stick with high fantasy, whatever the abstract limits of the applicability of the CRPG formula to fiction might be.

Our subject for today — Darklands, the first CRPG ever released by MicroProse Software — might be described as the rebuttal to the case made by the Worlds of Ultima games, in that its failings point to some of the intrinsic limits of the simulation-oriented approach. Then again, maybe not; today, perhaps even more so than when it was new, this is a game with a hardcore fan base who love it with a passion, even as other players, like the one who happens to be writing this article, see it as rather collapsing under the weight of its ambition and complexity. Whatever your final verdict on it, it’s undeniable that Darklands is overflowing with original ideas for a genre which, even by the game’s release year of 1992, had long since settled into a set of established expectations. By upending so many of them, it became one of the most intriguing CRPGs ever made.

Darklands was the brainchild of Arnold Hendrick, a veteran board-game, wargame, tabletop-RPG, and console-videogame designer who joined MicroProse in 1985, when it was still known strictly as a maker of military simulations. As the first MicroProse employee hired only for a design role — he had no programming or other technical experience whatsoever — he began to place his stamp on the company’s products immediately. It was Hendrick who first had the germ of an idea that Sid Meier, MicroProse’s star programmer/designer, turned into Pirates!, the first MicroProse game to depart notably from the company’s established formula. In addition to Pirates!, for which he continued to serve as a scenario designer and historical consultant even after turning the lead-designer reins over to Meier, Hendrick worked on other games whose feet were more firmly planted in MicroProse’s wheelhouse: titles like Gunship, Project Stealth Fighter, Red Storm Rising, M1 Tank Platoon, and Silent Service II.

“Wild” Bill Stealey, the flamboyant head of MicroProse, had no interest whatsoever in any game that wasn’t a military flight simulator. Still, he liked making money even more than he liked flying virtual aircraft, and by 1990 he wasn’t sure how much more he could grow his company if it continued to make almost nothing but military simulations and the occasional strategic wargame. Meanwhile he had Pirates! and Railroad Tycoon, the latter being Sid Meier’s latest departure from military games, to look at as examples of how successful non-traditional MicroProse games could be. Not knowing enough about other game genres to know what else might be a good bet for his company, he threw the question up to his creative and technical staff: “Okay, programmers, give me what you want to do, and tell me how much money you want to spend. We’ll find a way to sell it.”

And so Hendrick came forward with a proposal to make a CRPG called Darklands, to be set in the Germany of the 15th century, a time and place of dark forests and musty monasteries, Walpurgis Night and witch covens. It could become, Hendrick said, the first of a whole new series of historical CRPGs that, even as they provided MicroProse with an entrée into one of the most popular genres out there, would also leverage their reputation for making games with roots in the real world.

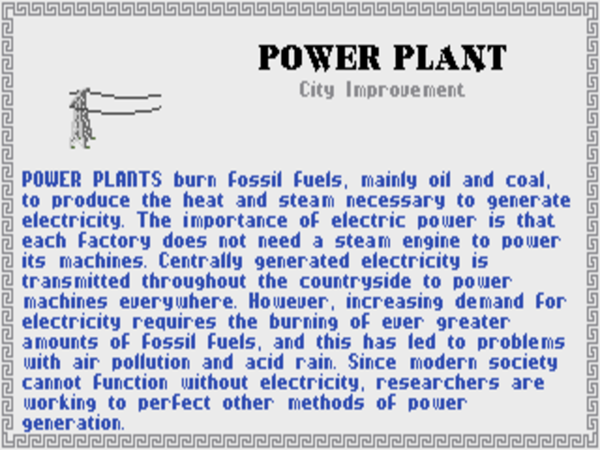

The typical CRPG, then as now, took place in a version of Medieval times that had only ever existed in the imagination of a modern person raised on Tolkien and Dungeons & Dragons. It ignored how appallingly miserable and dull life was for the vast majority of people who lived through the historical reality of the Middle Ages, with its plagues, wars, filth, hard labor, and nearly universal illiteracy. Although he was a dedicated student of history, with a university degree in the field, Hendrick too was smart enough to realize that there wasn’t much of a game to be had by hewing overly close to this mundane historical reality. But what if, instead of portraying a Medieval world as his own contemporaries liked to imagine it to have been, he conjured up the world of the Middle Ages as the people who had lived in it had imagined it to be? God and his many saints would take an active role in everyday affairs, monsters and devils would roam the forests, alchemy would really work, and those suspicious-looking folks who lived in the next village really would be enacting unspeakable rituals in the name of Satan every night. “This is an era before logic or science,” Hendrick wrote, “a time when anything is possible. In short, if Medieval Germans believed something to be true, in Darklands it might actually be true.”

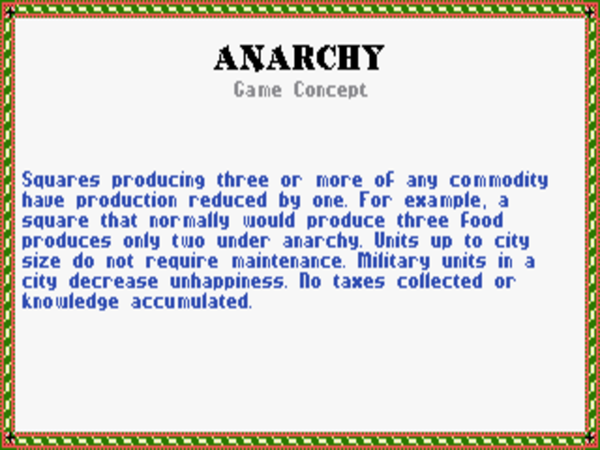

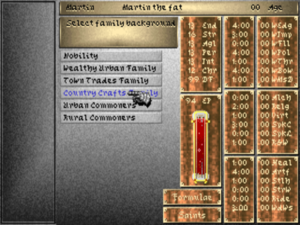

He wanted to incorporate an interwoven tapestry of Medieval imagination and reality into Darklands: a magic system based on Medieval theories about alchemy; a pantheon of real saints to pray to, each able to grant her own special favors; a complete, lovingly detailed map of 15th-century Germany and lands adjacent, over which you could wander at will; hundreds of little textual vignettes oozing with the flavor of the Middle Ages. To make it all go, he devised a set of systems the likes of which had never been seen in a CRPG, beginning with a real-time combat engine that let you pause it at any time to issue orders; its degree of simulation would be so deep that it would include penetration values for various weapons against various materials (thus ensuring that a vagabond with rusty knife could never, ever kill a full-fledged knight in shining armor). The character-creation system would be so detailed as to practically become a little game in itself, asking you not so much to roll up each character as live out the life story that brought her to this point: bloodline, occupations, education (such as it was for most in the Middles Ages), etc.

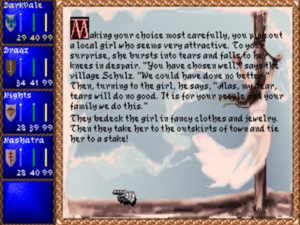

Character creation in Darklands is really, really complicated. And throughout the game, the spidery font superimposed on brown-sauce backgrounds will make your eyes bleed.

All told, it was one heck of a proposition for a company that had never made a CRPG before. Had Stealey been interested enough in CRPGs to realize just how unique the idea was, he might have realized as well how doubtful its commercial prospects were in a market that seemed to have little appetite for any CRPG that didn’t hew more or less slavishly to the Dungeons & Dragons archetype. But Stealey didn’t realize, and so Darklands got the green light in mid-1990. What followed was a tortuous odyssey; it became the most protracted and expensive development project MicroProse had ever funded.

We’ve seen in some of my other recent articles how companies like Sierra and Origin, taking stock of escalating complexity in gameplay and audiovisuals and their inevitable companion of escalating budgets, began to systematize the process of game development around this time. And we’ve at least glimpsed as well how such systematization could be a double-edged sword, leading to creatively unsatisfied team members and final products with something of a cookie-cutter feel.

MicroProse, suffice to say, didn’t go that route. Stealey took a hands-off approach to all projects apart from his beloved flight simulators, allowing his people to freelance their way through them. For all the drawbacks of rigid hierarchies and strict methodologies, the Darklands project could have used an injection of exactly those things. It was plagued by poor communication and outright confusion from beginning to end, as Arnold Hendrick and his colleagues improvised like mad in the process of making a game that was like nothing any of them had ever tried to make before.

Hendrick today forthrightly acknowledges that his own performance as project leader was “terrible.” Too often, the right hand didn’t know what the left was doing. An example cited by Hendrik involves Jim Synoski, the team’s first and most important programmer. For some months at the beginning of the project, he believed he was making essentially a real-time fighting game; while that was in fact some of what Darklands was about, it was far from the sum total of the experience. Once made aware at last that his combat code would need to interact with many other modules, he managed to hack the whole mess together, but it certainly wasn’t pretty. It seems there wasn’t so much as a design document for the team to work from — just a bunch of ideas in Hendrick’s head, imperfectly conveyed to everyone else.

The first advertisement for Darklands appeared in the March 1991 issue of Computer Gaming World. The actual product wouldn’t materialize until eighteen months later.

It’s small wonder, then, that Darklands went so awesomely over time and over budget; the fact that MicroProse never cancelled it likely owes as much to the sunk-cost fallacy as anything else. Hendrick claims that the game cost as much as $3 million to make in the end — a flabbergasting number that, if correct, would easily give it the crown of most expensive computer game ever made at the time of its release. Indeed, even a $2 million price tag, the figure typically cited by Stealey, would also qualify it for that honor. (By way of perspective, consider that Origin Systems’s epic CRPG Ultima VII shipped the same year as Darklands with an estimated price tag of $1 million.)

All of this was happening at the worst possible time for MicroProse. Another of Stealey’s efforts to expand the company’s market share had been an ill-advised standup-arcade version of F-15 Strike Eagle, MicroProse’s first big hit. The result, full of expensive state-of-the-art graphics hardware, was far too complex for the quarter-eater market; it flopped dismally, costing MicroProse a bundle. Even as that investment was going up in smoke, Stealey, acting again purely on the basis of his creative staff’s fondest wishes, agreed to challenge the likes of Sierra by making a line of point-and-click graphic adventures. Those products too would go dramatically over time and over budget.

Stealey tried to finance these latest products by floating an initial public offering in October of 1991. By June of 1992, on the heels of an announcement that not just Darklands but three other major releases as well would not be released that quarter — more fruit of Stealey’s laissez-faire philosophy of game development — the stock tumbled to almost 25 percent below its initial price. A stench of doom was beginning to surround the company, despite such recent successes as Civilization.

Games, like most creative productions, generally mirror the circumstances of their creation. This fact doesn’t bode well for Darklands, a project which started in chaos and ended, two years later, in a panicked save-the-company scramble.

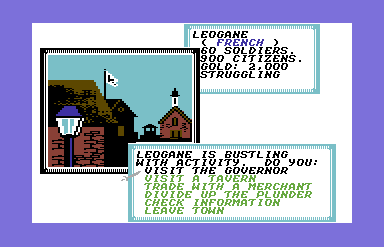

If you squint hard enough at Darklands, you can see its roots in Pirates!, the first classic Arnold Hendrick helped to create at MicroProse. As in that game, Darklands juxtaposes menu-driven in-town activities, written in an embodied narrative style, with more free-form wanderings over the territories that lie between the towns. But, in place of the straightforward menu of six choices in Pirates!, your time in the towns of Darklands becomes a veritable maze of twisty little passages; you start the game in an inn, but from there can visit a side street or a main street, which in turn can lead you to the wharves or the market, dark alleys or a park, all with yet more things to see and do. Because all of these options are constantly looping back upon one another — it’s seldom clear if the side street from this menu is the same side street you just visited from that other menu — just trying to buy some gear for your party can be a baffling undertaking for the beginner.

Thus, in spite of the superficial interface similarities, we see two radically opposing approaches to game design in Pirates! and Darklands. The older game emphasizes simplicity and accessibility, being only as complex as it needs to be to support the fictional experience it wants to deliver. But Darklands, for its part, piles on layer after layer of baroque detail with gleeful abandon. One might say that here the complexity is the challenge; learning to play the entirety of Darklands at all requires at least as much time and effort as getting really, truly good at a game like Pirates!.

The design dialog we see taking place here has been with us for a long time. Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax, the co-creators of the first incarnation of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, parted ways not long afterward thanks largely to a philosophical disagreement about how their creation should evolve. Arneson saw the game as a fairly minimalist framework to enable a shared storytelling session, while Gygax saw it as something more akin to the complex wargames on which he’d cut his teeth. Gygax, who would go on to write hundreds of pages of fiddly rules for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, his magnum opus, was happily cataloging and quantifying every variant of pole arm used in Medieval times when an exasperated Arneson finally lost his cool: “It’s a pointy thing on the end of a stick!” Your appreciation for Darklands must hinge on whether you are a Gary Gygax or a Dave Arneson in spirit. I know to which camp I belong; while there is a subset of gamers who truly enjoy Darkland‘s type of complexity — and more power to them for it — I must confess that I’m not among them.

In an interview conducted many years after the release of Darklands, Arnold Hendrick himself put his finger on what I consider to be its core problem: “Back then, game systems were often overly complicated, and attention to gameplay was often woefully lacking. These days, there’s a much better balance between gameplay and the human psychology of game players and the game systems underlying that gameplay.” Simply put, there are an awful lot of ideas in Darklands which foster complexity, but don’t foster what ought to be the ultimate arbitrator in game design: Fun. Modern designers often talk about an elusive sense of “flow” — a sense by the player that all of a game’s parts merge into a harmonious whole which makes playing for hours on end all too tempting. For this player at least, Darklands is the polar opposite of this ideal. Not only is it about as off-putting a game as I’ve ever seen at initial startup, but it continues always, even after a certain understanding has begun to dawn, to be a game of disparate parts: a character-generation game, a combat game, a Choose Your Own Adventure-style narrative, a game of alchemical crafting. There are enough original ideas here for ten games, but it never becomes clear why they absolutely, positively all need to be in this one. Darklands, in other words, is kind of a muddle.

Your motivation for adventuring in Medieval Germany in the first place is one of Darklands‘s original ideas in CRPG design. Drawing once again comparisons to Pirates!, Darklands dispenses with any sort of overarching plot as a motivating force. Instead, like your intrepid corsair of the earlier game, your party of four has decided simply “to bring everlasting honor and glory to your names.” If you play for long enough, something of a larger plot will eventually begin to emerge, involving a Satan-worshiping cult and a citadel dedicated to the demon Baphomet, but even after rooting out the cult and destroying the citadel the game doesn’t end.

In place of an overarching plot, Darklands relies on incidents and anecdotes, from a wandering knight challenging you to a duel to a sinkhole that swallows up half your party. While these are the products of a human writer (presumably Arnold Hendrick for the most part), their placements in the world are randomized. To improve your party’s reputation and earn money, you undertake a variety of quests of the “take item A to person B” or “go kill monster C” variety. All of this too is procedurally generated. Indeed, you begin a new game of Darklands by choosing the menu option “Create a New World.” Although the geography of Medieval Germany won’t change from game to game, most of what you’ll find in and around the towns is unique to your particular created world. It all adds up to a game that could literally, as MicroProse’s marketers didn’t hesitate to declare, go on forever.

But, as all too commonly happens with these things, it’s a little less compelling in practice than it sounds in theory. I’ve gone on record a number of times now with my practical objections to generative narratives. Darklands too often falls prey to the problems that are so typical of the approach. The quests you pick up, lacking as they do any larger relationship to a plot or to the world, are the very definition of FedEx quests, bereft of any interest beyond the reputation and money they earn for you. And, while it can sometimes surprise you with an unexpectedly appropriate and evocative textual vignette, the game more commonly hews to the predictable here as well. Worse, it has a dismaying tendency to show you the same multiple-choice vignettes again and again, pulling you right out of the fiction.

And yet the vignettes are actually the most narratively interesting parts of the game; it will be some time before you begin to see them at all. As in so many other vintage CRPGs, the bulk of your time at the beginning of Darklands is spent doing boring things in the name of earning the right to eventually do less boring things. In this case, you’ll likely have to spend several hours roaming the vacant back streets of whatever town you happen to begin in, seeking out and killing anonymous bands of robbers, just to build up your party enough to leave the starting town.

The open-ended structure works for Pirates! because that game dispenses with this puritanical philosophy of design. It manages to be great fun from the first instant by keeping the pace fast and the details minimal, even as it puts a definite time limit on your career, thus tempting you to play again and again in order to improve on your best final score. Darklands, by contrast, doesn’t necessarily end even when your party is too old to adventure anymore (aging becomes a factor after about age thirty); you can just make new characters and continue where the old ones left off, in the same world with the same equipment, quests, and reputation. Darklands, then, ends only when you get tired of it. Just when that exact point arrives will doubtless differ markedly from player to player, but it’s guaranteed to be anticlimactic.

The ostensible point of Darklands‘s enormously complex systems of character creation, alchemy, religion, and combat is to evoke its chosen time and place as richly as possible. One might even say the same about its lack of an overarching epic plot; such a thing doesn’t exist in the books of history and legend to which the game is so determined to be so faithful. Yet I can’t help but feel that this approach — that of trying to convey the sense of a time and place through sheer detail — is fundamentally misguided. Michael Bate, a designer of several games for Accolade during the 1980s, coined the term “aesthetic simulations” for historical games that try to capture the spirit of their subject matter rather than every piddling detail. Pirates! is, yet again, a fine example of this approach, as is the graceful, period-infused but not period-heavy-handed writing of the 1992 adventure game The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes.

The writing in Darklands falls somewhat below that standard. It isn’t terrible, but it is a bit graceless, trying to make up for in concrete detail what it isn’t quite able to conjure in atmosphere. So, we get money that is laboriously explicated in terms of individual pfenniges, groschen, and florins, times of day described in terms that a Medieval monk would understand (Matins, Latins, Prime, etc.), and lots of off-putting-to-native-English-speakers German names, but little real sense of being in Medieval Germany.

Graphically as well, the game is… challenged. Having devoted most of their development efforts to 3D vehicular simulators during the 1980s, MicroProse’s art department plainly struggled to adapt to the demands of other genres. Even an unimpeachable classic like Sid Meier’s Civilization achieves its classic status despite rather than because of its art; visually, it’s a little garish compared to what other studios were putting out by this time. But Darklands is much more of a visual disaster, a conflicting mishmash of styles that sometimes manage to look okay in isolation, such as in the watercolor-style backgrounds to many of the textual vignettes. Just as often, though, it verges on the hideous; the opening movie is so absurdly amateurish that, according to industry legend, some people actually returned the game after seeing it, thinking they must have gotten a defective disk or had an incompatible video card.

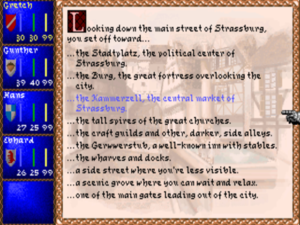

One of Darklands‘s more evocative vignettes, with one of its better illustrations as a backdrop. Unfortunately, you’re likely to see this same vignette and illustration several times, with a decided sense of diminishing returns.

But undoubtedly the game’s biggest single problem, at the time of its release and to some extent still today, was all of the bugs. Even by the standards of an industry at large which was clearly struggling to come to terms with the process of making far more elaborate games than had been seen in the previous decade, Darklands stood out upon its belated release in August of 1992 for its woefully under-baked state. Whether this was despite or because of its extended development cycle remains a question for debate. What isn’t debatable, however, is that it was literally impossible to complete Darklands in its initial released state, and that, even more damningly, a financially pressured MicroProse knew this and released it anyway. To their credit, the Darklands team kept trying to fix the game after its release, with patch after patch to its rickety code base. The patches eventually numbered at least nine in all, a huge quantity for long-suffering gamers to acquire at a time when they could only be distributed on physical floppy disks or via pricey commercial online services like CompuServe. After about a year, the team managed to get the game into a state where it only occasionally did flaky things, although even today it remains far from completely bug-free.

By the time the game reached this reasonably stable state, however, the damage had been done. It sold fairly well in its first month or two, but then came a slew of negative reviews and an avalanche of returns that actually exceeded new sales for some time; Darklands thus managed the neat trick of continuing to be a drain on MicroProse’s precarious day-to-day finances even after it had finally been released. Hendrick had once imagined a whole line of similar historical CRPGs; needless to say, that didn’t happen.

Combined with the only slightly less disastrous failure of the new point-and-click graphic-adventure line, Darklands was directly responsible for the end of MicroProse as an independent entity. In December of 1993, with the company’s stock now at well under half of its IPO price and the creditors clamoring, a venture-capital firm arranged a deal whereby MicroProse was acquired by Spectrum Holobyte, known virtually exclusively for a truly odd pairing of products: the home-computer version of the casual game Tetris and the ultra-hardcore flight simulator Falcon. The topsy-turvy world of corporate finance being what it was, this happened despite the fact that MicroProse’s total annual sales were still several times that of Spectrum Holobyte.

Stealey, finding life unpleasant in a merged company where he was no longer top dog, quit six months later. His evaluation of the reasons for MicroProse’s collapse was incisive enough in its fashion:

You have to be known for something. We were known for two things [military simulators and grand-strategy games], but we tried to do more. I think that was a big mistake. I should have been smarter than that. I should have stuck with what we were good at.

I’ve been pretty hard on Darklands in this article, a stance for which I don’t quite feel a need to apologize; I consider it a part of my duty as your humble scribe to call ’em like I see ’em. Yet there is far more to Darklands‘s legacy than a disappointing game which bankrupted a company. Given how rare its spirit of innovation has been in CRPG design, plenty of players in the years since its commercial vanishing performance have been willing to cut it a lot of slack, to work hard to enjoy it on its own terms. For reasons I’ve described at some length now, I can’t manage to join this group, but neither can I begrudge them their passion.

But then, Darklands has been polarizing its players from the very beginning. Shortly after the game’s release, Scorpia, Computer Gaming World magazine’s famously opinionated adventure-game columnist, wrote a notably harsh review of it, concluding that it “might have been one of the great ones” but instead “turns out to be a game more to be avoided than anything else.” Johnny L. Wilson, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, was so bothered by her verdict that he took the unusual step of publishing a sidebar response of his own. It became something of a template for future Darklands apologies by acknowledging the game’s obvious flaws yet insisting that its sheer uniqueness nevertheless made it worthwhile. (“The game is as repetitive as Scorpia and some of the game’s online critics have noted. One comes across some of the same encounters over and over. Yet only occasionally did I find this disconcerting.”) He noted as well that he personally hadn’t seen many of the bugs and random crashes which Scorpia had described in her review. Perhaps, he mused, his computer was just an “immaculate contraption” — or perhaps Scorpia’s was the opposite. In response to the sidebar, Wilson was castigated by his magazine’s readership, who apparently agreed with Scorpia much more than with him and considered him to have undermined his own acknowledged reviewer.

The reader response wasn’t the only interesting postscript to this episode. Wilson:

Later, after 72 hours of playing around with minor quests and avoiding the main plot line of Darklands, I decided it was time to finish the game. I had seven complete system crashes in less than an hour and a half once I decided to jump in and finish the game. I didn’t really have an immaculate contraption, I just hadn’t encountered the worst crashes because I hadn’t filled my upper memory with the system-critical details of the endgame. Scorpia hadn’t overreacted to the crashes. I just hadn’t seen how bad it was because I was fooling around with the game instead of trying to win. Since most players would be trying to win, Scorpia’s review was more valid than my sidebar. Ah, well, that probably isn’t the worst thing I’ve ever done when I thought I was being fair.

This anecdote reveals what may be a deciding factor — in addition to a tolerance for complexity for its own sake — as to whether one can enjoy Darklands or not. Wilson had been willing to simply inhabit its world, while the more goal-oriented Scorpia approached it as she would any other CRPG — i.e., as a game that she wanted to win. As a rather plot-focused, goal-oriented player myself, I naturally sympathize more with her point of view.

In the end, then, the question of where the point of failure lies in Darklands is one for the individual player to answer. Is Darklands as a whole a very specific sort of failure, a good idea that just wasn’t executed as well as it might have been? Or does the failure lie with the CRPG format itself, which this game stretched beyond the breaking point? Or does the real failure lie with the game’s first players, who weren’t willing to look past the bugs and other occasional infelicities to appreciate what could have been a whole new type of CRPG? I know where I stand, but my word is hardly the final one.

Given the game’s connection to the real world and its real cultures, so unusual to the CRPG genre, perhaps the most interesting question of all raised by Darklands is that of the appropriate limits of gamefication. A decade before Darklands‘s release, the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop RPG was embroiled in a controversy engendered by God-fearing parents who feared it to be an instrument of Satanic indoctrination. In actuality, the creators of the game had been wise enough to steer well clear of any living Western belief system. (The Deities & Demigods source book did include living native-American, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese religions, which raises some troublesome questions of its own about cultural appropriation and respect, but wasn’t quite the same thing as what the angry Christian contingent was complaining about.)

It’s ironic to note that much of the content which Evangelical Christians believed to be present in Dungeons & Dragons actually is present in Darklands, including the Christian God and Satan and worshipers of both. Had Darklands become successful enough to attract the attention of the same groups who objected so strongly to Dungeons & Dragons, there would have been hell to pay. Arnold Hendrick had lived through the earlier controversy from an uncomfortably close vantage point, having been a working member of the tabletop-game industry at the time it all went down. In his designer’s notes in Darklands‘s manual, he thus went to great pains to praise the modern “vigorous, healthy, and far more spiritual [Catholic] Church whose quiet role around the globe is more altruistic and beneficial than many imagine.” Likewise, he attempted to separate modern conceptions of Satanism and witchcraft from those of Medieval times. Still, the attempt to build a wall between the Christianity of the 15th century and that of today cannot be entirely successful; at the end of the day, we are dealing with the same religion, albeit in two very different historical contexts.

Opinions vary as to whether the universe in which we live is entirely mechanistic, reducible to the interactions of concrete, understandable, computable physical laws. But it is clear that a computer simulation of a world must be exactly such a thing. In short, a simulation leaves no room for the ineffable. And yet Darklands chooses to grapple, to an extent unrivaled by almost any other game I’m aware of, with those parts of human culture that depend upon a belief in the ineffable. By bringing Christianity into its world, it goes to a place virtually no other game has dared approach. Its vending-machine saints reduce a religion — a real, living human faith — to a game mechanic. Is this okay? Or are there areas of the human experience which ought not to be turned into banal computer code? The answer must be in the eye — and perhaps the faith — of the beholder.

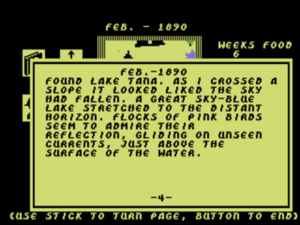

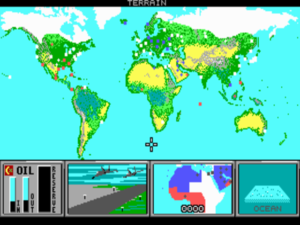

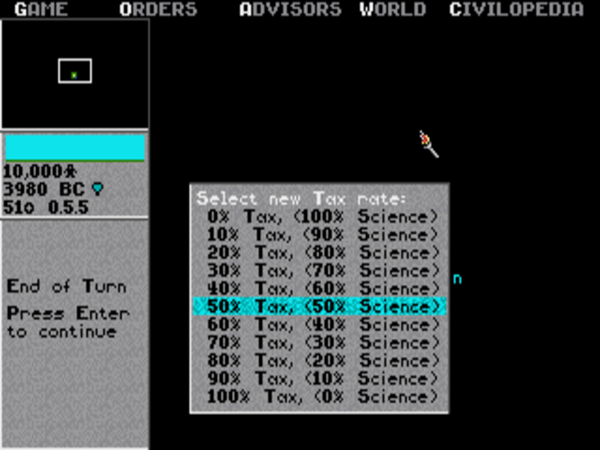

Darklands‘s real-time-with-pause combat system. The interface here is something of a disaster, and the visuals too leave much to be desired, but the core idea is sound.

By my lights, Darklands is more of a collection of bold ideas than a coherent game, more of an experiment in the limits of CRPG design than a classic example of same. Still, in a genre which is so often in thrall to the tried and true, its willingness to experiment can only be applauded.

For sometimes experiments yield rich rewards, as the most obvious historical legacy of this poor-selling, obscure, bug-ridden game testifies. Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk, the joint CEOs of Bioware at the time that studio made the Baldur’s Gate series of CRPGs, have acknowledged lifting the real-time-with-pause combat systems in those huge-selling and much-loved games directly out of Darklands. Since the Baldur’s Gate series’s heyday around the turn of the millennium, dozens if not hundreds of other CRPGs have borrowed the same system second-hand from Bioware. Such is the way that innovation diffuses itself through the culture of game design. So, the next time you fire up a Steam-hosted extravaganza like Pillars of Eternity, know that part of the game you’re playing owes its existence to Darklands. Lumpy and imperfect though it is in so many ways, we could use more of its spirit of bold innovation today — in CRPG design and, indeed, across the entire landscape of interactive entertainment.

(Sources: the book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay; Computer Gaming World of March 1991, February 1992, May 1992, September 1992, December 1992, January 1993, and June 1994; Commodore Magazine of September 1987; Questbusters of November 1992; Compute! of October 1993; PC Zone of September 2001; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of January 17 1992; New York Times of June 13 1993. Online sources include Matt Barton’s interview with Arnold Hendrick, Just Adventure‘s interview with Johnny L. Wilson, and Arnold Hendrick’s discussion of Darklands in the Steam forum.

Darklands is available for purchase on GOG.com.)