Most of the academic papers about 3D graphics that John Carmack so assiduously studied during the 1990s stemmed from, of all times and places, the Salt Lake City, Utah, of the 1970s. This state of affairs was a credit to one man by the name of Dave Evans.

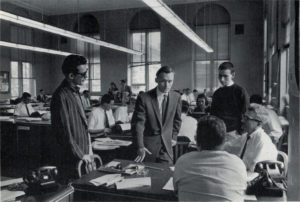

Born in Salt Lake City in 1924, Evans was a physicist by training and an electrical engineer by inclination, who found his way to the highest rungs of computing research by way of the aviation industry. By the early 1960s, he was at the University of California, Berkeley, where he did important work in the field of time-sharing, taking the first step toward the democratization of computing by making it possible for multiple people to use one of the ultra-expensive big computers of the day at the same time, each of them accessing it through a separate dumb terminal. During this same period, Evans befriended one Ivan Sutherland, who deserves perhaps more than any other person the title of Father of Computer Graphics as we know them today.

For, in the course of earning his PhD at MIT, Sutherland developed a landmark software application known as Sketchpad, the first interactive computer-based drawing program of any stripe. Sketchpad did not do 3D graphics. It did, however, record its user’s drawings as points and lines on a two-dimensional plane. The potential for adding a third dimension to its Flatland-esque world — a Z coordinate to go along with X and Y — was lost on no one, least of all Sutherland himself. His 1963 thesis on Sketchpad rocketed him into the academic stratosphere.

In 1964, at the ripe old age of 26, Sutherland succeeded J.C.R. Licklider as head of the computer division of the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the most remarkable technology incubator in computing history. Alas, he proved ill-suited to the role of administrator: he was too young, too introverted — just too nerdy, as a later generation would have put it. But during the unhappy year he spent there before getting back to the pure research that was his real passion, he put the University of Utah on the computing map, largely as a favor to his friend Dave Evans.

Evans may have left Salt Lake City more than a decade ago, but he remained a devout Mormon, who found the counterculture values of the Berkeley of the 1960s rather uncongenial. So, he had decided to take his old alma mater up on an offer to come home and build a computer-science department there. Sutherland now awarded said department a small ARPA contract, one fairly insignificant in itself. What was significant was that it brought the University of Utah into the ARPA club of elite research institutions that were otherwise clustered on the coasts. An early place on the ARPANET, the predecessor to the modern Internet, was not the least of the perks which would come its way as a result.

Evans looked for a niche for his university amidst the august company it was suddenly joining. The territory of time-sharing was pretty much staked; extensive research in that field was already going full steam ahead at places like MIT and Berkeley. Ditto networking and artificial intelligence and the nuts and bolts of hardware design. Computer graphics, though… that was something else. There were smart minds here and there working on them — count Ivan Sutherland as Exhibit Number One — but no real research hubs dedicated to them. So, it was settled: computer graphics would become the University of Utah’s specialty. In what can only be described as a fantastic coup, in 1968 Evans convinced Sutherland himself to abandon the East Coast prestige of Harvard, where he had gone after leaving his post as the head of ARPA, in favor of the Mormon badlands of Utah.

Things just snowballed from there. Evans and Sutherland assembled around them an incredible constellation of bright young sparks, who over the course of the next decade defined the terms and mapped the geography of the field of 3D graphics as we still know it today, writing papers that remain as relevant today as they were half a century ago — or perchance more so, given the rise of 3D games. For example, the two most commonly used algorithms for calculating the vagaries of light and shade in 3D games stem directly from the University of Utah: Gouraud shading was invented by a Utah student named Henri Gouraud in 1971, while Phong shading was invented by another named Bui Tuong Phong in 1973.

But of course, lots of other students passed through the university without leaving so indelible a mark. One of these was Jim Clark, who would still be semi-anonymous today if he hadn’t gone on to become an entrepreneur who co-founded two of the most important tech companies of the late twentieth century.

When you’ve written as many capsule biographies as I have, you come to realize that the idea of the truly self-made person is for the most part a myth. Certainly almost all of the famous names in computing history were, long before any of their other qualities entered into the equation, lucky: lucky in their time and place of birth, in their familial circumstances, perhaps in (sad as it is to say) their race and gender, definitely in the opportunities that were offered to them. This isn’t to disparage their accomplishments; they did, after all, still need to have the vision to grasp the brass ring of opportunity and the talent to make the most of it. Suffice to say, then, that luck is a prerequisite but the farthest thing from a guarantee.

Every once in a while, however, I come across someone who really did almost literally make something out of nothing. One of these folks is Jim Clark. If today as a soon-to-be octogenarian he indulges as enthusiastically as any of his Old White Guy peers in the clichéd trappings of obscene wealth, from the mansions, yachts, cars, and wine to the Victoria’s Secret model he has taken for a fourth wife, he can at least credibly claim to have pulled himself up to his current station in life entirely by his own bootstraps.

Clark was born in 1944, in a place that made Salt Lake City seem like a cosmopolitan metropolis by comparison: the small Texas Panhandle town of Plainview. He grew up dirt poor, the son of a single mother living well below the poverty line. Nobody expected much of anything from him, and he obliged their lack of expectations. “I thought the whole world was shit and I was living in the middle of it,” he recalls.

An indifferent student at best, he was expelled from high school his junior year for telling a teacher to go to hell. At loose ends, he opted for the classic gambit of running away to sea: he joined the Navy at age seventeen. It was only when the Navy gave him a standardized math test, and he scored the highest in his group of recruits on it, that it began to dawn on him that he might actually be good at something. Encouraged by a few instructors to pursue his aptitude, he enrolled in correspondence courses to fill his free time when out plying the world’s oceans as a crewman on a destroyer.

Ten years later, in 1971, the high-school dropout, now six years out of the Navy and married with children, found himself working on a physics PhD at Louisiana State University. Clark:

I noticed in Physics Today an article that observed that physicists getting PhDs from places like Harvard, MIT, Yale, and so on didn’t like the jobs they were getting. And I thought, well, what am I doing — I’m getting a PhD in physics from Louisiana State University! And I kept thinking, well, I’m married, and I’ve got these obligations. By this time, I had a second child, so I was real eager to get a good job, and I just got discouraged about physics. And a friend of mine pointed to the University of Utah as having a computer-graphics specialty. I didn’t know much about it, but I was good with geometry and physics, which involves a lot of geometry.

So, Clark applied for a spot at the University of Utah and was accepted.

But, as I already implied, he didn’t become a star there. His 1974 thesis was entitled “3D Design of Free-Form B-Spline Surfaces”; it was a solid piece of work addressing a practical problem, but not anything to really get the juices flowing. Afterward, he spent half a decade bouncing around from campus to campus as an adjunct professor: the Universities of California at Santa Cruz and Berkeley, the New York Institute of Technology, Stanford. He was fairly miserable throughout. As an academic of no special note, he was hired primarily as an instructor rather than a researcher, and he wasn’t at all cut out for the job, being too impatient, too irascible. Proving the old adage that the child is the father of the man, he was fired from at least one post for insubordination, just like that angry teenager who had once told off his high-school teacher. Meanwhile he went through not one but two wives. “I was in this kind of downbeat funk,” he says. “Dark, dark, dark.”

It was now early 1979. At Stanford, Clark was working right next door to Xerox’s famed Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), which was inventing much of the modern paradigm of computing, from mice and menus to laser printers and local-area networking. Some of the colleagues Clark had known at the University of Utah were happily ensconced over there. But he was still on the outside looking in. It was infuriating — and yet he was about to find a way to make his mark at last.

Hardware engineering at the time was in the throes of a revolution and its backlash, over a technology that went by the mild-mannered name of “Very Large Scale Integration” (VLSI). The integrated circuit, which packed multiple transistors onto a single microchip, had been invented at Texas Instruments at the end of the 1950s, and had become a staple of computer design already during the following decade. Yet those early implementations often put only a relative handful of transistors on a chip, meaning that they still required lots of chips to accomplish anything useful. A turning point came in 1971 with the Intel 4004, the world’s first microprocessor — i.e., the first time that anyone put the entire brain of a computer on a single chip. Barely remarked at the time, that leap would result in the first kit computers being made available for home users in 1975, followed by the Trinity of 1977, the first three plug-em-in-and-go personal computers suitable for the home. Even then, though, there were many in the academic establishment who scoffed at the idea of VLSI, which required a new, in some ways uglier approach to designing circuitry. In a vivid illustration that being a visionary in some areas doesn’t preclude one from being a reactionary in others, many of the folks at PARC were among the scoffers. Look how far we’ve come doing things one way, they said. Why change?

A PARC researcher named Lynn Conway was enraged by such hidebound thinking. A rare female hardware engineer, she had made scant progress to date getting her point of view through to the old boy’s club that surrounded her at PARC. So, broadening her line of attack, she wrote a paper about the basic techniques of modern chip design, and sent it out to a dozen or so universities along with a tempting offer: if any students or faculty wished to draw up schematics for a chip of their own and send them to her, she would arrange to have the chip fabricated in real silicon and sent back to its proud parent. The point of it all was just to get people to see the potential of VLSI, not to push forward the state of the art. And indeed, just as she had expected, almost all of the designs she received were trivially simple by the standards of even the microchip industry of 1979: digital time keepers, adding machines, and the like. But one was unexpectedly, even crazily complex. Alone among the submissions, it bore a precautionary notice of copyright, from one James Clark. He called his creation the Geometry Engine.

The Geometry Engine was the first and, it seems likely, only microchip that Jim Clark ever personally attempted to design in his life. It was created in response to a fundamental problem that had been vexing 3D modelers since the very beginning: that 3D graphics required shocking quantities of mathematical calculations to bring to life, scaling almost exponentially with the complexity of the scene to be depicted. And worse, the type of math they required was not the type that the researchers’ computers were especially good at.

Wait a moment, some of you might be saying. Isn’t math the very thing that computers do? It’s right there in the name: they compute things. Well, yes, but not all types of math are created equal. Modern computers are also digital devices, meaning they are naturally equipped to deal only with discrete things. Like the game of DOOM, theirs is a universe of stair steps rather than smooth slopes. They like integer numbers, not decimals. Even in the 1960s and 1970s, they could approximate the latter through a storage format known as floating point, but they dealt with these floating-point numbers at least an order of magnitude slower than they did whole numbers, as well as requiring a lot more memory to store them. For this reason, programmers avoided them whenever possible.

And it actually was possible to do so a surprisingly large amount of the time. Most of what computers were commonly used for could be accomplished using only whole numbers — for example, by using Euclidean division that yields a quotient and a remainder in place of decimal division. Even financial software could be built using integers only to count the total number of cents rather than floating-point values to represent dollars and cents. 3D-graphics software, however, was one place where you just couldn’t get around them. Creating a reasonably accurate mathematical representation of an analog 3D space forced you to use floating-point numbers. And this in turn made 3D graphics slow.

Jim Clark certainly wasn’t the first person to think about designing a specialized piece of hardware to lift some of the burden from general-purpose computer designs, an add-on optimized for doing the sorts of mathematical operations that 3D graphics required and nothing else. Various gadgets along these lines had been built already, starting a decade or more before his Geometry Engine. Clark was the first, however, to think of packing it all onto a single chip — or at worst a small collection of them — that could live on a microcomputer’s motherboard or on a card mounted in a slot, that could be mass-produced and sold in the thousands or millions. His description of his “slave processor” sounded disarmingly modest (not, it must be said, a quality for which Clark is typically noted): “It is a four-component vector, floating-point processor for accomplishing three basic operations in computer graphics: matrix transformations, clipping, and mapping to output-device coordinates [i.e., going from an analog world space to pixels in a digital raster].” Yet it was a truly revolutionary idea, the genesis of the graphical processing units (GPUs) of today, which are in some ways more technically complex than the CPUs they serve. The Geometry Engine still needed to use floating-point numbers — it was, after all, still a digital device — but the old engineering doctrine that specialization yields efficiency came into play: it was optimized to do only floating-point calculations, and only a tiny subset of all the ones possible at that, just as quickly as it could.

The Geometry Engine changed Clark’s life. At last, he had something exciting and uniquely his. “All of these people started coming up and wanting to be part of my project,” he remembers. Always an awkward fit in academia, he turned his thinking in a different direction, adopting the mindset of an entrepreneur. “He reinvented his relationship to the world in a way that is considered normal only in California,” writes journalist Michael Lewis in a book about Clark. “No one who had been in his life to that point would be in it ten years later. His wife, his friends, his colleagues, even his casual acquaintances — they’d all be new.” Clark himself wouldn’t hesitate to blast his former profession in later years with all the fury of a professor scorned.

I love the metric of business. It’s money. It’s real simple. You either make money or you don’t. The metric of the university is politics. Does that person like you? Do all these people like you enough to say, “Yeah, he’s worthy?”

But by whatever metric, success didn’t come easy. The Geometry Engine and all it entailed proved a harder sell with the movers and shakers in commercial computing than it had with his colleagues at Stanford. It wasn’t until 1982 that he was able to scrape together the funding to found a company called Silicon Graphics, Incorporated (SGI), and even then he was forced to give 85 percent of his company’s shares to others in order to make it a reality. Then it took another two years after that to actually ship the first hardware.

The market segment SGI was targeting is one that no longer really exists. The machines it made were technically microcomputers, being built around microprocessors, but they were not intended for the homes of ordinary consumers, nor even for the cubicles of ordinary office workers. These were much higher-end, more expensive machines than those, even if they could fit under a desk like one of them. They were called workstation computers. The typical customer spent tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars on them in the service of some highly demanding task or another.

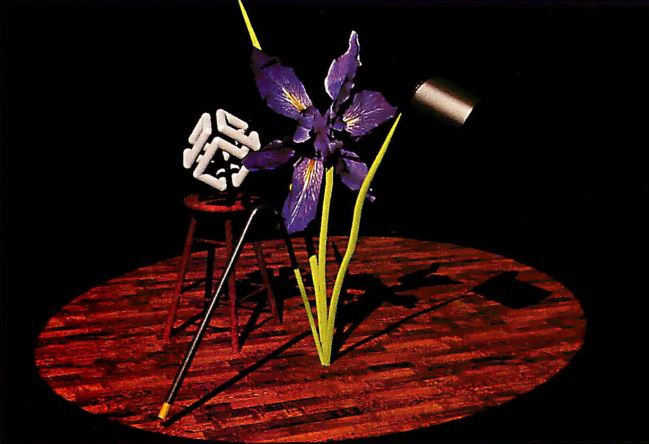

In the case of the SGI machines, of course, that task was almost always related to graphics, usually 3D graphics. Their expense wasn’t bound up with their CPUs; in the beginning, these were fairly plebeian chips from the Motorola 68000 series, the same line used in such consumer-grade personal computers as the Apple Macintosh and the Commodore Amiga. No, the justification of their high price tags rather lay with their custom GPUs, which even in 1984 already went far beyond the likes of Clark’s old Geometry Engine. An SGI GPU was a sort of black box for 3D graphics: feed it all of the data that constituted a scene on one side, and watch a glorious visual representation emerge at the other, thanks to an array of specialized circuitry designed for that purpose and no other.

Now that it had finally gotten off the ground, SGI became very successful very quickly. Its machines were widely used in staple 3D applications like computer-aided industrial design (CAD) and flight simulation, whilst also opening up new vistas in video and film production. They drove the shift in Hollywood from special effects made using miniature models and stop-motion techniques dating back to the era of King Kong to the extensive use of computer-generated imagery (CGI) that we see even in the purportedly live-action films of today. (Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were among SGI’s first and best customers.) “When a moviegoer rubbed his eyes and said, ‘What’ll they think of next?’,” writes Michael Lewis, “it was usually because SGI had upgraded its machines.”

The company peaked in the early 1990s, when its graphics workstations were the key to CGI-driven blockbusters like Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park. Never mind the names that flashed by in the opening credits; everyone could agree that the computer-generated dinosaurs were the real stars of Jurassic Park. SGI was bringing in over $3 billion in annual revenue and had close to 15,000 employees by 1993, the year that movie was released. That same year, President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore came out personally to SGI’s offices in Silicon Valley to celebrate this American success story.

SGI’s hardware subsystem for graphics, the beating heart of its business model, was known in 1993 as the RealityEngine2. This latest GPU was, wrote Byte magazine in a contemporary article, “richly parallel,” meaning that it could do many calculations simultaneously, in contrast to a traditional CPU, which could only execute one instruction at a time. (Such parallelism is the reason that modern GPUs are so often used for some math-intensive non-graphical applications, such as crypto-currency mining and machine learning.) To support this black box and deliver to its well-heeled customers a complete turnkey solution for all their graphics needs, SGI had also spearheaded an open-source software library for 3D applications, known as the Open Graphics Library, or OpenGL. Even the CPUs in its latest machines were SGI’s own; it had purchased a maker of same called MIPS Technologies in 1990.

But all of this success did not imply a harmonious corporation. Jim Clark was convinced that he had been hard done by back in 1982, when he was forced to give up 85 percent of his brainchild in order to secure the funding he needed, then screwed over again when he was compelled by his board to give up the CEO post to a former Hewlett Packard executive named Ed McCracken in 1984. The two men had been at vicious loggerheads for years; Clark, who could be downright mean when the mood struck him, reduced McCracken to public tears on at least one occasion. At one memorable corporate retreat intended to repair the toxic atmosphere in the board room, recalls Clark, “the psychologist determined that everyone else on the executive committee was passive aggressive. I was just aggressive.”

Clark claims that the most substantive bone of contention was McCracken’s blasé indifference to the so-called low-end market, meaning all of those non-workstation-class personal computers that were proliferating in the millions during the 1980s and early 1990s. If SGI’s machines were advancing by leaps and bounds, these consumer-grade computers were hopscotching on a rocket. “You could see a time when the PC would be able to do the sort of graphics that [our] machines did,” says Clark. But McCracken, for one, couldn’t see it, was content to live fat and happy off of the high prices and high profit margins of SGI’s current machines.

He did authorize some experiments at the lower end, but his heart was never in it. In 1990, SGI deigned to put a limited subset of the RealityEngine smorgasbord onto an add-on card for Intel-based personal computers. Calling it IrisVision, it hopefully talked up its price of “under $5000,” which really was absurdly low by the company’s usual standards. What with its complete lack of software support and its way-too-high price for this marketplace, IrisVision went nowhere, whereupon McCracken took the failure as a vindication of his position. “This is a low-margin business, and we’re a high-margin company, so we’re going to stop doing that,” he said.

Despite McCracken’s indifference, Clark eventually managed to broker a deal with Nintendo to make a MIPS microprocessor and an SGI GPU the heart of the latter’s Nintendo 64 videogame console. But he quit after yet another shouting match with McCracken in 1994, two years before it hit the street.

He had been right all along about the inevitable course of the industry, however undiplomatically he may have stated his case over the years. Personal computers did indeed start to swallow the workstation market almost at the exact point in time that Clark bailed. The profits from the Nintendo deal were rich, but they were largely erased by another of McCracken’s pet projects, an ill-advised acquisition of the struggling supercomputer maker Cray. Meanwhile, with McCracken so obviously more interested in selling a handful of supercomputers for millions of dollars each than millions upon millions of consoles for a few hundred dollars each, a group of frustrated SGI employees left the company to help Nintendo make the GameCube, the followup to the Nintendo 64, on their own. It was all downhill for SGI after that, bottoming out in a 2009 bankruptcy and liquidation.

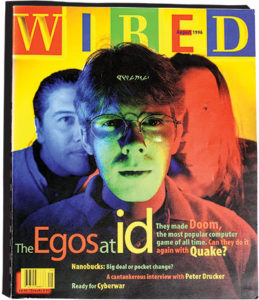

As for Clark, he would go on to a second entrepreneurial act as remarkable as his first, abandoning 3D graphics to make a World Wide Web browser with Marc Andreessen. We will say farewell to him here, but you can read the story of his second company Netscape’s meteoric rise and fall elsewhere on this site.

Now, though, I’d like to return to the scene of SGI’s glory days, introducing in the process three new starring players. Gary Tarolli and Scott Sellers were talented young engineers who were recruited to SGI in the 1980s; Ross Smith was a marketing and business-development type who initially worked for MIPS Technologies, then ended up at SGI when it acquired that company in 1990. The three became fast friends. Being of a younger generation, they didn’t share the contempt for everyday personal computers that dominated among their company’s upper management. Whereas the latter laughed at the primitiveness of games like Wolfenstein 3D and Ultima Underworld, if they bothered to notice them at all, our trio saw a brewing revolution in gaming, and thought about how much it could be helped along by hardware-accelerated 3D graphics.

Convinced that there was a huge opportunity here, they begged their managers to get into the gaming space. But, still smarting from the recent failure of IrisVision, McCracken and his cronies rejected their pleas out of hand. (One of the small mysteries in this story is why their efforts never came to the attention of Jim Clark, why an alliance was never formed. The likely answer is that Clark had, by his own admission, largely removed himself from the day-to-day running of SGI by this time, being more commonly seen on his boat than in his office.) At last, Tarolli, Sellers, Smith, and some like-minded colleagues ran another offer up the flagpole. You aren’t doing anything with IrisVision, they said. Let us form a spinoff company of our own to try to sell it. And much to their own astonishment, this time management agreed.

They decided to call their new company Pellucid — not the best name in the world, sounding as it did rather like a medicine of some sort, but then they were still green at all this. The technology they had to peddle was a couple of years old, but it still blew just about anything else in the MS-DOS/Windows space out of the water, being able to display 16 million colors at a resolution of 1024 X 768, with 3D acceleration built-in. (Contrast this with the SVGA card found in the typical home computer of the time, which could do 256 colors at 640 X 480, with no 3D affordances). Pellucid rebranded the old IrisVision the ProGraphics 1024. Thanks to the relentless march of chip-fabrication technology, they found that they could now manufacture it cheaply enough to be able to sell it for as little as $1000 — still pricey, to be sure, but a price that some hardcore gamers, as well as others with a strong interest in having the best graphics possible, might just be willing to pay.

The problem, the folks at Pellucid soon came to realize, was a well-nigh intractable deadlock between the chicken and the egg. Without software written to take advantage of its more advanced capabilities, the ProGraphics 1024 was just another SVGA graphics card, selling for a ridiculously high price. So, consumers waited for said software to arrive. Meanwhile software developers, seeing the as-yet non-existent installed base, saw no reason to begin supporting the card. Breaking this logjam must require a concentrated public-relations and developer-outreach effort, the likes of which the shoestring spinoff couldn’t possibly afford.

They thought they had done an end-run around the problem in May of 1993, when they agreed, with the blessing of SGI, to sell Pellucid kit and caboodle to a major up-and-comer in consumer computing known as Media Vision, which currently sold “multimedia upgrade kits” consisting of CD-ROM drives and sound cards. But Media Vision’s ambitions knew no bounds: they intended to branch out into many other kinds of hardware and software. With proven people like Stan Cornyn, a legendary hit-maker from the music industry, on their management rolls and with millions and millions of dollars on hand to fund their efforts, Media Vision looked poised to dominate.

It seemed the perfect landing place for Pellucid; Media Vision had all the enthusiasm for the consumer market that SGI had lacked. The new parent company’s management said, correctly, that the ProGraphics 1024 was too old by now and too expensive to ever become a volume product, but that 3D acceleration’s time would come as soon as the current wave of excitement over CD-ROM and multimedia began to ebb and people started looking for the next big thing. When that happened, Media Vision would be there with a newer, more reasonably priced 3D card, thanks to the people who had once called themselves Pellucid. It sounded pretty good, even if in the here and now it did seem to entail more waiting around than anything else.

There was just one stumbling block: “Media Vision was run by crooks,” as Scott Sellers puts it. In April of 1994, a scandal erupted in the business pages of the nation’s newspapers. It turned out that Media Vision had been an experiment in “fake it until you make it” on a gigantic scale. Its founders had engaged in just about every form of malfeasance imaginable, creating a financial house of cards whose honest revenues were a minuscule fraction of what everyone had assumed them to be. By mid-summer, the company had blown away like so much dust in the wind, still providing income only for the lawyers who were left to pick over the corpse. (At least two people would eventually be sent to prison for their roles in the conspiracy.) The former Pellucid folks were left as high and dry as everyone else who had gotten into bed with Media Vision. All of their efforts to date had led to the sale of no more than 2000 graphics cards.

That same summer of 1994, a prominent Silicon Valley figure named Gordon Campbell was looking for interesting projects in which to invest. Campbell had earned his reputation as one of the Valley’s wise men through a company called Chips and Technologies (C&T), which he had co-founded in 1984. One of those hidden movers in the computer industry, C&T had largely invented the concept of the chipset: chips or small collections of them that could be integrated directly into a computer’s motherboard to perform functions that used to be placed on add-on cards. C&T had first made a name for itself by reducing IBM’s bulky nineteen-chip EGA graphics card to just four chips that were cheaper to make and consumed less power. Campbell’s firm thrived alongside the cost-conscious PC clone industry, which by the beginning of the 1990s was rendering IBM itself, the very company whose products it had once so unabashedly copied, all but irrelevant. Onboard video, onboard sound, disk controllers, basic firmware… you name it, C&T had a cheap, good-enough-for-the-average-consumer chipset to handle it.

But now Campbell had left C&T “in pursuit of new opportunities,” as they say in Valley speak. Looking for a marketing person for one of the startups in which he had invested a stake, he interviewed a young man named Ross Smith who had SGI on his résumé — always a plus. But the interview didn’t go well. Campbell:

It was the worst interview I think I’ve ever had. And so finally, I just turned to him and I said, “Okay, your heart’s not in this interview. What do you really want to do?”

And he kind of looks surprised and says, well, there are these two other guys, and we want to start a 3D-graphics company. And the next thing I know, we had set up a meeting. And we had, over a lot of beers, a discussion which led these guys to all come and work at my office. And that set up the start of 3Dfx.

It seemed to all of them that, after all of the delays and blind alleys, it truly was now or never to make a mark. For hardware-accelerated 3D graphics were already beginning to trickle down into the consumer space. In standup arcades, games like Daytona USA and Virtua Fighter were using rudimentary GPUs. Ditto the Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation, the latest in home-videogame consoles, both which were on the verge of release in Japan, with American debuts expected in 1995. Meanwhile the software-only, 2.5D graphics of DOOM were taking the world of hardcore computer gamers by storm. The men behind 3Dfx felt that the next move must surely seem obvious to many other people besides themselves. The only reason the masses of computer-game players and developers weren’t clamoring for 3D graphics cards already was that they didn’t yet realize what such gadgets could do for them.

Still, they were all wary of getting back into the add-on board market, where they had been burned so badly before. Selling products directly to consumers required retail access and marketing muscle that they still lacked. Instead, following in the footsteps of C&T, they decided to sell a 3D chipset only to other companies, who could then build it into add-on boards for personal computers, standup-arcade machines, whatever they wished.

At the same time, though, they wanted their technology to be known, in exactly the way that the anonymous chipsets made by C&T were not. In the pursuit of this aspiration, Gordon Campbell found inspiration from another company that had become a household name despite selling very little directly to consumers. Intel had launched the “Intel Inside” campaign in 1990, just as the era of the PC clone was giving way to a more amorphous commodity architecture. The company introduced a requirement that the makers of computers which used its CPUs include the Intel Inside logo on their packaging and on the cases of the computers themselves, even as it made the same logo the centerpiece of a standalone advertising campaign in print and on television. The effort paid off; Intel became almost as identified with the Second Home Computer Revolution in the minds of consumers as was Microsoft, whose own logo showed up on their screens every time they booted into Windows. People took to calling the emerging duopoly the “Wintel” juggernaut, a name which has stuck around to this day.

So, it was decided: a requirement to display a similarly snazzy 3Dfx logo would be written into that company’s contracts as well. The 3Dfx name itself was a vast improvement over Pellucid. As time went on, 3Dfx would continue to display a near-genius for catchy branding: “Voodoo” for the chipset itself, “GLide” for the software library that controlled it. All of this reflected a business savvy the likes of which hadn’t been seen from Pellucid, that was a credit both to Campbell’s steady hand and the accumulating experience of the other three partners.

But none of it would have mattered without the right product. Campbell told his trio of protégés in no uncertain terms that they were never going to make a dent in computer gaming with a $1000 video card; they needed to get the price down to a third of that at the most, which meant the chipset itself could cost the manufacturers who used it in their products not much more than $100 a pop. That was a tall order, especially considering that gamers’ expectations of graphical fidelity weren’t diminishing. On the contrary: the old Pellucid card hadn’t even been able to do 3D texture mapping, a failing that gamers would never accept post-DOOM.

But none of it would have mattered without the right product. Campbell told his trio of protégés in no uncertain terms that they were never going to make a dent in computer gaming with a $1000 video card; they needed to get the price down to a third of that at the most, which meant the chipset itself could cost the manufacturers who used it in their products not much more than $100 a pop. That was a tall order, especially considering that gamers’ expectations of graphical fidelity weren’t diminishing. On the contrary: the old Pellucid card hadn’t even been able to do 3D texture mapping, a failing that gamers would never accept post-DOOM.

It was left to Gary Tarolli and Scott Sellers to figure out what absolutely had to be in there, such as the aforementioned texture mapping, and what they could get away with tossing overboard. Driven by the remorseless logic of chip-fabrication costs, they wound up going much farther with the tossing than they ever could have imagined when they started out. There could be no talk of 24-bit color or unusually high resolutions: 16-bit color (offering a little over 65,000 onscreen shades) at a resolution of 640 X 480 would be the limit.[1]A resolution of 800 X 600 was technically possible using the Voodoo chipset, but using this resolution meant that the programmer could not use a vital affordance known as Z-buffering. For this reason, it was almost never seen in the wild. Likewise, they threw out the capability of handling any polygons except for the simplest of them all, the humble triangle. For, they realized, you could make almost any solid you liked by combining triangular surfaces together. With enough triangles in your world — and their chipset would let you have up to 1 million of them — you needn’t lament the absence of the other polygons all that much.

Sellers had another epiphany soon after. Intel’s latest CPU, to which gamers were quickly migrating, was the Pentium. It had a built-in floating-point co-processor which was… not too shabby, actually. It should therefore be possible to take the first phase of the 3D-graphics pipeline — the modeling phase — out of the GPU entirely and just let the CPU handle it. And so another crucial decision was made: they would concern themselves only with the rendering or rasterization phase, which was a much greater challenge to tackle in software alone, even with a Pentium. Another huge piece of the puzzle was thus neatly excised — or rather outsourced back to the place where it was already being done in current games. This would have been heresy at SGI, whose ethic had always been to do it all in the GPU. But then, they were no longer at SGI, were they?

Undoubtedly their bravest decision of all was to throw out any and all 2D-graphics capabilities — i.e., the neat rasters of pixels used to display Windows desktops and word processors and all of those earlier, less exciting games. Makers of Voodoo boards would have to include a cable to connect the existing, everyday graphics cards inside their customers’ machines to their new 3D ones. When you ran non-3D applications, the Voodoo card would simply pass the video signal on to the monitor unchanged. But when you fired up a 3D game, it would take over from the other board. A relay inside made a distinctly audible click when this happened. Far from a bug, gamers would soon come to consider the noise a feature.”Because you knew it was time to have fun,” as Ross Smith puts it.

It was a radical plan, to be sure. These new cards would be useful only for games, would have no other purpose whatsoever; there would be no justifying this hardware purchase to the parents or the spouse with talk of productivity or educational applications. Nevertheless, the cost savings seemed worth it. After all, almost everyone who initially went out to buy the new cards would already have a perfectly good 2D video card in their computer. Why make them pay extra to duplicate those functions?

The final design used just two custom chips. One of them, internally known as the T-Rex (Jurassic Park was still in the air), was dedicated exclusively to the texture mapping that had been so conspicuously missing from the Pellucid board. Another, called the FBI (“Frame Buffer Interface”), did everything else required in the rendering phase. Add to this pair a few less exciting off-the-shelf chips and four megabytes worth of RAM chips, put it on a board with the appropriate connectors, and you had yourself a 3Dfx Voodoo GPU.

Needless to say, getting this far took some time. Tarolli, Sellers, and Smith spent the last half of 1994 camped out in Campbell’s office, deciding what they wanted to do and how they wanted to do it and securing the funding they needed to make it happen. Then they spent all of 1995 in offices of their own, hiring about a dozen people to help them, praying all the time that no other killer product would emerge to make all of their efforts moot. While they worked, the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation did indeed arrive on American shores, becoming the first gaming devices equpped with 3D GPUs to reach American homes in quantity. The 3Dfx crew were not overly impressed by either console — and yet they found the public’s warm reception of the PlayStation in particular oddly encouraging. “That showed, at a very rudimentary level, what could be done with 3D graphics with very crude texture mapping,” says Scott Sellers. “And it was pretty abysmal quality. But the consumers were just eating it up.”

They got their first finished chipsets back from their Taiwanese fabricator at the end of January 1996, then spent Super Bowl weekend soldering them into place and testing them. There were a few teething problems, but in the end everything came together as expected. They had their 3D chipset, at the beginning of a year destined to be dominated by the likes of Duke Nukem 3D and Quake. It seemed the perfect product for a time when gamers couldn’t get enough 3D mayhem. “If it had been a couple of years earlier,” says Gary Tarolli, “it would have been too early. If it had been a couple of years later, it would have been too late.” As it was, they were ready to go at the Goldilocks moment. Now they just had to sell their chipset to gamers — which meant they first had to sell it to game developers and board makers.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: the books The Dream Machine by M. Mitchell Waldrop Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age by Michael A. Hiltzik, and The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story by Michael Lewis; Byte of May 1992 and November 1993; InfoWorld of April 22 1991 and May 31 1993; Next Generation of October 1997; ACM’s Computer Graphics journal of July 1982; Wired of January 1994 and October 1994. Online sources include the Computer History Museum’s “oral histories” with Jim Clark, Forest Baskett, and the founders of 3Dfx; Wayne Carlson’s “Critical History of Computer Graphics and Animation”; “Fall of Voodoo” by Ernie Smith at Tedium; Fabian Sanglard’s reconstruction of the workings of the Voodoo 1 chips; “Famous Graphics Chips: 3Dfx’s Voodoo” by Dr. Jon Peddie at the IEEE Computer Society’s site; an internal technical description of the Voodoo technology archived at bitsavers.org.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A resolution of 800 X 600 was technically possible using the Voodoo chipset, but using this resolution meant that the programmer could not use a vital affordance known as Z-buffering. For this reason, it was almost never seen in the wild. |

|---|