This blog has become, among other things, an examination of good and bad game-design practices down through the years, particularly within the genre of adventure games. I’ve always tried to take the subject seriously, and have even dared to hope that some of these writings might be of practical use to someone — might help designers of the present or future make better games. But, for reasons that I hope everyone can understand, I’ve spent much more time illuminating negative than positive examples of puzzle design. The fact is, I don’t feel much compunction about spoiling bad puzzles. Spoiling the great puzzles, however, is something I’m always loath to do. I want my readers to have the thrill of tackling those for themselves.

Unfortunately, this leaves the situation rather unbalanced. If you’re a designer looking for tips from the games of the past, it certainly helps to have some positive as well as negative examples to look at. And even if you just read this blog to experience (or re-experience) these old games through the sensibility of your humble author here, you’re missing out if all you ever hear about are the puzzles that don’t work. So, when my reader and supporter Casey Muratori wrote to me to suggest an article that singles out some great puzzles for detailed explication and analysis, it sounded like a fine idea to me.

It’s not overly difficult to generalize what makes for fair or merely “good” puzzles. They should be reasonably soluble by any reasonably intelligent, careful player, without having to fall back on the tedium of brute-forcing them or the pointlessness of playing from a walkthrough. As such, the craft of making merely good or fair puzzles is largely subsumed in lists of what not to do — yes, yet more negative reinforcements! — such as Graham Nelson’s “Bill of Player’s Rights” or Ron Gilbert’s “Why Adventure Games Suck and What We Can Do About It.” It’s much more difficult, however, to explain what makes a brilliant, magical puzzle. In any creative discipline, rules will only get you so far; at some point, codification must make way for the ineffable. Still, we’ll do the best we can today, and see if we can’t tease some design lessons out of ten corking puzzles from adventure games of yore.

Needless to say, there will be spoilers galore in what follows, so if you haven’t played these games, and you think you might ever want to, you should absolutely do so before reading about them here. All ten games are found in my personal Hall of Fame and come with my highest recommendation. As that statement would indicate, I’ve restricted this list to games I’ve already written about, meaning that none of those found here were published after 1992. I’ve split the field evenly between parser-driven text adventures and point-and-click graphic adventures. If you readers enjoy and/or find this article useful, then perhaps it can become a semi-regular series going forward.

And now, with all that said, let’s accentuate the positive for once and relive some classic puzzles that have been delighting their players for decades.

1. Getting past the dragon in Adventure

By Will Crowther and Don Woods, public domain, 1977.

How it works: Deep within the bowels of Colossal Cave, “a huge green dragon bars the way!” Your objective, naturally, is to get past him to explore the area beyond. But how to get him out of the way? If you throw your axe at him, it “bounces harmlessly off the dragon’s thick scales.” If you unleash your fierce bird friend on him, who earlier cleared a similarly troublesome snake out of your way, “the little bird attacks the green dragon, and in an astounding flurry gets burnt to a cinder.” If you simply try to “attack dragon,” the game mocks you: “With what? Your bare hands?” You continue on in this way until, frustrated and thoroughly pissed off, you type, “Yes,” in response to that last rhetorical question. And guess what? It wasn’t a rhetorical question: “Congratulations! You have just vanquished a dragon with your bare hands! (Unbelievable, isn’t it?)”

Why it works: In many ways, this is the most dubious puzzle in this article. (I do know how to make an entrance, don’t I?) It seems safe to say that the vast majority of people who have “solved” it have done so by accident, which is not normally a sign of good puzzle design. Yet classic text adventures especially were largely about exploring the possibility space, seeing what responses you could elicit. The game asks you a question; why not answer it, just to see what it does?

This is an early example of a puzzle that could never have worked absent the parser — absent its approach to interactivity as a conversation between game and player. How could you possibly implement something like this using point and click? I’m afraid a dialog box with a “YES” and “NO” just wouldn’t work. In text, though, the puzzle rewards the player’s sense of whimsy — rewards the player, one might even say, for playing in the right spirit. Interactions like these are the reason some of us continue to love text adventures even in our modern era of photo-realistic graphics and surround sound.

Our puzzling design lesson: A puzzle need not be complicated to delight — need barely be a puzzle at all! — if it’s executed with wit and a certain joie de vivre.

2. Exploring the translucent maze in Enchanter

By Marc Blank and David Lebling, Infocom, 1983

How it works: As you’re exploring the castle of the mad wizard Krill, you come upon a maze of eight identical rooms in the basement. Each location is “a peculiar room, whose cream-colored walls are thin and translucent.” All of the rooms are empty, the whole area seemingly superfluous. How strange.

Elsewhere in the castle, you’ve discovered (or will discover) a few other interesting items. One is an old book containing “The Legend of the Unseen Terror”:

This legend, written in an ancient tongue, goes something like this: At one time a shapeless and formless manifestation of evil was disturbed from millennia of sleep. It was so powerful that it required the combined wisdom of the leading enchanters of that age to conquer it. The legend tells how the enchanters lured the Terror "to a recess deep within the earth" by placing there a powerful spell scroll. When it had reached the scroll, the enchanters trapped it there with a spell that encased it in the living rock. The Terror was so horrible that none would dare speak of it. A comment at the end of the narration indicates that the story is considered to be quite fanciful; no other chronicles of the age mention the Terror in any form.

And you’ve found a map, drawn in pencil. With a start, you realize that it corresponds exactly to the map you’ve drawn of the translucent maze, albeit with an additional, apparently inaccessible room located at point P:

B J

! / \

! / \

! / \

! K V

! / \

! / \

! / \

R-------M F

\ /

\ /

\ /

H P

Finally, you’ve found a badly worn pencil, with a point and an eraser good for just two uses each.

And so you put the pieces together. The Terror and the “powerful spell scroll” mentioned in the book are encased in the “living rock” of the maze in room P. The pencil creates and removes interconnections between the rooms. You need to get to room P to recover the scroll, which you’ll need to defeat Krill. But you can’t allow the Terror to escape and join forces with Krill. A little experimentation — which also causes you to doom the world to endless darkness a few times, but there’s always the restore command, right? — reveals that the Terror moves one room per turn, just as you do. So, your objective must be to let him out of room P, but trap him in another part of the maze before he can get to room B and freedom. You need to give him a path to freedom to get him moving out of room P, then cut it off.

There are many possible solutions. One is to go to room H, then draw a line connecting P and F. Sensing a path to freedom, the Terror will move to room F, whereupon you erase the connection you just drew. As you do that, the Terror moves to room V, but you erase the line between V and M before he can go further, trapping him once again. Now, you have just enough pencil lead left to draw a line between H and P and recover the scroll.

Why it works: Solving this puzzle comes down to working out how a system functions, then exploiting it to do your bidding. (Small wonder so many hackers have found text adventures so appealing over the years!) First comes the great mental leap of connecting these four disparate elements which you’ve found scattered about: an empty maze, a book of legends, a map, and a pencil. Then, after that great “a-ha!” moment, you get the pleasure of working out the mechanics of the Terror’s movements and finally of putting together your plan and carrying it out. Once you understand how everything works, this final exercise is hardly a brain burner, but it’s nevertheless made much more enjoyable by the environment’s dynamism. You feel encouraged to sit down with your map and work out your unique approach, and the game responds as you expect it to. This simulational aspect, if you will, stands in marked contrast to so many static adventure-game puzzles of the “use X on Y because the designer wants you to” variety.

It’s worth taking note as well of the technology required to implement something like this. It demands a parser capable of understanding a construction as complicated as “draw line from H to P,” a game engine capable of re-jiggering map connections and rewriting room descriptions on the fly, and even a measure of artificial intelligence, including a path-finding algorithm, for the Terror. Nobody other than Infocom could have implemented a puzzle of this dynamic complexity in 1983. I’ve often noted that the keystone of Infocom’s design genius was their subtly advanced technology in comparison to anyone else working in their field; this puzzle provides fine proof of what I mean by that.

Our puzzling design lesson: Technology isn’t everything in game design, but it isn’t nothing either; the tools you choose to work with have a direct impact on the types of puzzles you can attempt. A corollary to this statement is that the technology which goes into design affordances is often far more subtle than that which allows whiz-bang graphics and sound.

3. Getting the babel fish in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

By Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky, Infocom, 1984

How it works: You’ve escaped planet Earth just seconds before its destruction at the hands of a Vogon Constructor Fleet. You’re now in the hold of one of the Vogon ships:

Vogon Hold

This is a squalid room filled with grubby mattresses, unwashed cups, and unidentifiable bits of smelly alien underwear. A door lies to port, and an airlock lies to starboard.

There is a satchel here.

In the corner is a glass case with a switch and a keyboard.

It looks like the glass case contains:

an atomic vector plotter

Along one wall is a tall dispensing machine.

That dispensing machine contains babel fish, which, when inserted into your ear, will allow you to understand the many strange alien languages you’ll soon be encountering. Rather than belabor this famously extended puzzle point by point, I’ll just provide you with a transcript of the steps you need to go through to solve it. In real life, of course, you would spend much more time bumbling and fumbling than does our ideal player here.

>examine machine

The dispenser is tall, has a button at around eye-level, and says "Babel Fish" in large letters. Anything dispensed would probably come out the slot at around knee-level. It bears a small label which reads "Another fine product of the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation."

>i

You have:

no tea

a thing your aunt gave you which you don't know what it is

a towel

It looks like your gown contains:

pocket fluff

The Hitchhiker's Guide

an electronic Sub-Etha signaling device

a loose pile of junk mail

a toothbrush

a flathead screwdriver

>push button

A single babel fish shoots out of the slot. It sails across the room and through a small hole in the wall, just under a metal hook.

>remove gown

Okay, you're no longer wearing your gown.

>hang gown on hook

The gown is now hanging from the hook, covering a tiny hole.

>push button

A single babel fish shoots out of the slot. It sails across the room and hits the dressing gown. The fish slides down the sleeve of the gown and falls to the floor, vanishing through the grating of a hitherto unnoticed drain.

>put towel on drain

The towel completely covers the drain.

>push button

A single babel fish shoots out of the slot. It sails across the room and hits the dressing gown. The fish slides down the sleeve of the gown and falls to the floor, landing on the towel. A split-second later, a tiny cleaning robot whizzes across the floor, grabs the fish, and continues its breakneck pace toward a tiny robot panel at the base of the wall. The robot zips through the panel, and is gone.

>cover panel with satchel

Okay, the satchel is lying on its side in front of the tiny robot panel.

>push button

A single babel fish shoots out of the slot. It sails across the room and hits the dressing gown. The fish slides down the sleeve of the gown and falls to the floor, landing on the towel. A split-second later, a tiny cleaning robot whizzes across the floor, grabs the fish, and continues its breakneck pace toward a tiny robot panel at the base of the wall. The robot plows into the satchel, sending the babel fish flying through the air in a graceful arc. A small upper-half-of-the-room cleaning robot flies into the room, catches the babel fish (which is all the flying junk it can find), and exits.

>put mail on satchel

Okay, the loose pile of junk mail is now sitting on the satchel.

>push button

A single babel fish shoots out of the slot. It sails across the room and hits the dressing gown. The fish slides down the sleeve of the gown and falls to the floor, landing on the towel. A split-second later, a tiny cleaning robot whizzes across the floor, grabs the fish, and continues its breakneck pace toward a tiny robot panel at the base of the wall. The robot plows into the satchel, sending the babel fish flying through the air in a graceful arc surrounded by a cloud of junk mail. Another robot flies in and begins madly collecting the cluttered plume of mail. The babel fish continues its flight, landing with a loud "squish" in your ear.

Why it works: This is easily the most famous text-adventure puzzle of all time, one whose reputation for difficulty was so extreme in the 1980s that Infocom took to selling tee-shirts emblazoned with “I got the babel fish!” In truth, though, its reputation is rather exaggerated. There are other puzzles in Hitchhiker’s which rely heavily — perhaps a little too heavily — on the ability to think with the skewed logic of Douglas Adams. This puzzle, however, really isn’t one of them. It’s certainly convoluted and time-consuming, but it’s also both logical in a non-skewed sense and thoroughly satisfying to work out step by step. From the standpoint of the modern player, its only really objectionable aspects are the facts that you can easily arrive at it without having everything you need to solve it, and that you have a limited amount of tries — i.e., a limited number of spare babel fish — at your disposal. But if you have made sure to pick up everything that isn’t nailed down in the early part of the game, and if you use the save system wisely, there’s no reason you can’t solve this on your own and have immense fun doing so. It’s simply a matter of saving at each stage and experimenting to find out how to progress further. The fact that it can be comfortably solved in stages makes it far less infuriating than it might otherwise be. You always feel like you’re making progress — coming closer, step by step, to the ultimate solution. There’s something of a life lesson here: most big problems can be solved by first breaking them down into smaller problems and solving those one at a time.

Importantly, this puzzle is also funny, fitting in perfectly with Douglas Adams’s comedic conception of a universe not out so much to swat you dead all at once as to slowly annoy you to death with a thousand little passive-aggressive cuts.

Our puzzling design lesson: Too many adventure-game designers think that making a comedy gives them a blank check to indulge in moon logic when it comes to their puzzles. The babel fish illustrates that a puzzle can be both funny and fair.

4. Using the T-removing machine in Leather Goddesses of Phobos

By Steve Meretzky, Infocom, 1986

How it works: While exploring this ribald science-fiction comedy, Infocom’s last big hit, you come upon a salesman who wants to trade you something for the “odd machine” he carries. When you finally find the item he’s looking for and take possession of the machine, he gives you only the most cryptic description of its function: “‘It’s a TEE remover,’ he explains. You ponder what it removes — tea stains, hall T-intersections — even TV star Mr. T crosses your mind, until you recall that it’s only 1936.”

Experimentation will eventually reveal that this “tee-remover” is actually a T-remover. If you put something inside it and turn it on, said something becomes itself minus all of the letter Ts in its name. You need to use the machine to solve one clever and rather hilarious puzzle, turning a jar of untangling cream into unangling cream, thereby to save poor King Mitre’s daughter from a tragic fate:

In the diseased version of the legend commonly transmitted on Earth, Mitre is called Midas. The King was granted his wish that everything he touched would turn to gold. His greed caught up with him when he transformed even his own daughter into gold.

King Mitre's wish was, in fact, that everything he touched would turn to forty-five degree angles. No one has ever explained this strange wish; the most likely hypothesis is a sexual fetish. In any case, the tale has a similar climax, with Mitre turning his own daughter into a forty-five degree angle.

This is pretty funny in itself, but the greatest fun offered by the T-remover is in all the other places you can use it: on a tray (“It looks a little like Ray whatsisname from second grade.”); on a rabbit (“A bearded rabbi wearing a prayer shawl leaps out of the machine, recites a Torah blessing, and dashes off in search of a minyan.”); a raft (“It sinks like a stone. I guess a raf doesn’t float nearly as well as a raft.”); a pair of cotton balls (“Let’s just say that some poor male raccoon is speaking in a particularly high-pitched voice.”).

Why it works: The T-removing machine is sometimes held up as another puzzle concept that couldn’t possibly work in any other medium than text. I’m not sure if that’s literally true — later in this very list we’ll see another funny wordplay-based puzzle that does work inside a graphic adventure — but it certainly is true that no responsible producer would agree to pay for all the work required to implement all those one-off, just-for-fun responses in graphics. In text, though, they’re just a matter of an additional sentence or two.

Adventure designer Bob Bates likes to point out that the vast majority of what the player attempts to do will always be wrong; that’s just the nature of the endeavor. When she does one of these wrong things, the designer needs to do as much as possible to entertain her. A later generation would dub this the “juicy” approach to game design: rewarding curiosity and creativity, even if none of it contributes directly to the prosaic task of finishing the game. Steve Meretzky had a great puzzle already with the T-remover, King Mitre, and the untangling/unangling cream. He could have left it at that by coming up with excuses for why you couldn’t put other things in the T-remover. Instead he stayed faithful to his invention and implemented many alternatives alongside the “correct” use of the machine.

Our puzzling design lesson: Don’t ignore the “else” in the “if, then, else” of an adventure game. It makes your game feel like a living world rather than an arbitrary collection of logic gates to be navigated, and shows that you respect your player’s creativity.

5. Escaping the pirate Lafond in Plundered Hearts

By Amy Briggs, Infocom, 1987

How it works: Would I be engaging in too much gender stereotyping if I noted that the puzzles in the only Infocom game to be written by a woman often deal in social intelligence rather than abstract logic? This is another fairly lengthy sequence, so it’s best if I once again just show you what happens if you do everything correctly.

"Welcome, ma petite." Lafond bows you in.

Lafond's Bedroom

Lafond's bedroom shows all the outpourings of his megalomania. Royal hues of

purple and gold weigh down the hangings on the bed and the eastward window, as if trying to smother the moonbeam shining in.

Lafond is leering, lip curled.

A lace-covered table crouches beside a wing-backed chair in one corner. Sitting on the table is a green goblet, a blue goblet and a flagon.

"Have some wine." Lafond pours wine into two glasses, giving a blue one to you. "Drink this down. We have a long night ahead of us." He drains his own.

>drink wine

You empty the blue goblet of wine.

"Good girl," he says, "Let's see more cooperation of this sort."

Suddenly, the door slams open. It is Jamison, coatless, sword bared, his shirt ripped. "Thank God I am not too late. Leave, darling, before I skewer this dog to his bedposts," he cries. The scar on his cheek gleams coldly.

With a yell, Crulley and the butler jump out of the darkness behind him. Nicholas struggles, but soon lies unconscious on the floor.

"Take him to the dungeon," Lafond says, setting down his glass. "You, butler, stay nearby. I do not wish to be disturbed again.

"Now that we are rid of that intrusion, cherie, I will change into something more comfortable. Pour me more wine." He crosses to the wardrobe removing his coat and vest, turned slightly away from you.

>pour wine into green goblet

You fill the green goblet with wine.

"In private, call me Jean, or whatever endearment you choose, once I have approved it." Lafond is looking into the wardrobe.

>squeeze bottle into green goblet

You squeeze three colorless drops into the green goblet. You sense Lafond

hesitate, then continue primping.

The butler enters, laying a silver tray of cold chicken on the table. "The kitchen wench has gone, your grace. I took the liberty of fetching these

myself." He bows and leaves the room.

"Sprinkle some spices on the fowl, ma petite," Lafond says, donning a long brocade robe, his back to you. "They are hot, but delicious."

>get spices

You take a pinch of spices between your thumb and forefinger.

"Tsk. The cook has gone too far. She shall be 'leaving us' tomorrow." Lafond adjusts the lace at his neck.

>put spices on chicken

You sprinkle some spices on a wing and nibble it. The peppery heat hits you like a wave, leaving you gasping, eyes watering.

Lafond strolls to the table smiling slyly. "But you haven't finished pouring the wine." He tops off both glasses. "Which glass was mine? I seem to have forgotten." He points at the green goblet and smiles in a way that does not grant you confidence. "Is this it?"

>no

You shake your head, teeth clenched.

"Ah yes, of course." Lafond obligingly takes the blue goblet.

He inhales deeply of the bouquet of his wine, then turns to you. "You must think me very naive to fall for such a trick. I saw you pour something into one of these glasses -- although I cannot smell it." He switches goblets, setting the blue goblet into your nerveless grasp and taking up the other, smiling evilly. "Now you will drink from the cup intended for me."

>drink from blue goblet

You empty the blue goblet of wine.

"Good girl," he says. Lafond takes the leather bottle and drops it out the window. "You shall not need this. You may suffer no headaches in my employ."

He lifts his glass to drink, but stops. "Your father, for all his idiotic meddling in other people's business, is not a fool. I doubt you are, either." He calls in the butler, ordering him to empty the green goblet. The man reports no odd taste and returns to his post.

>get spices

You take a pinch of spices between your thumb and forefinger.

Lafond draws near, whispering indecencies. He caresses your lily white neck, his fingers ice-cold despite the tropic heat.

>throw spices at lafond

You blow the spices off your fingertips, directly into Lafond's face. He

sneezes, his eyes watering from the heat of the peppers. Reaching blindly for some wine, he instead upsets the table, shattering a glass. Lafond stumbles cursing out of the room, in search of relief.

>s

You run out -- into the butler's barrel chest and leering grin. You return to the bedroom, the butler following. "The governor said you were not to leave this room."

>z

Time passes...

The butler seems to be having some problems stifling a yawn.

>z

Time passes...

The butler's eyes are getting heavier.

>z

Time passes...

The butler collapses, head back, snoring loudly.

>s

You creep over the prostrate butler.

Why it works: Plundered Hearts is an unusually driven text adventure, in which the plucky heroine you play is constantly forced to improvise her way around the dangers that come at her from every direction. In that spirit, one can almost imagine a player bluffing her way through this puzzle on the first try by thinking on her feet and using her social intuition. Most probably won’t, mark you, but it’s conceivable, and that’s what makes it such a good fit with the game that hosts it. This death-defying tale doesn’t have time to slow down for complicated mechanical puzzles. This puzzle, on the other hand, fits perfectly with the kind of high-wire adventure story — adventure story in the classic sense — which this game wants to be.

Our puzzling design lesson: Do-or-die choke point should be used sparingly, but can serve a plot-heavy game well as occasional, exciting punctuations. Just make sure that they feel inseparable from the narrative unfolding around the player — not, as is the case with so many adventure-game puzzles, like the arbitrary thing the player has to do so that the game will feed her the next bit of story.

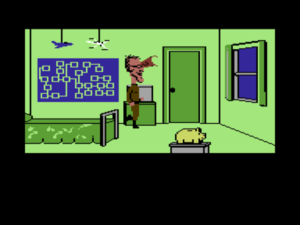

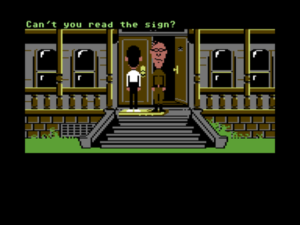

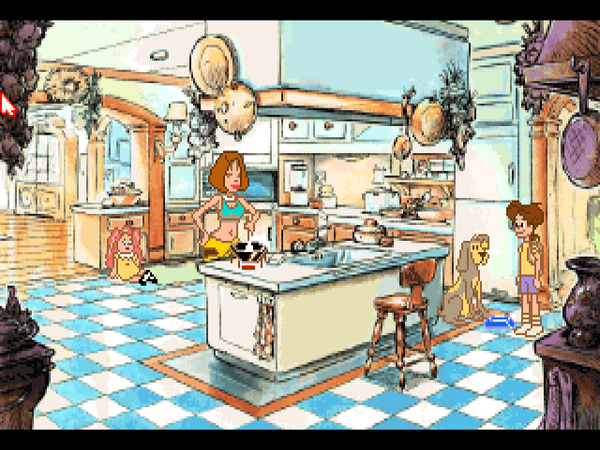

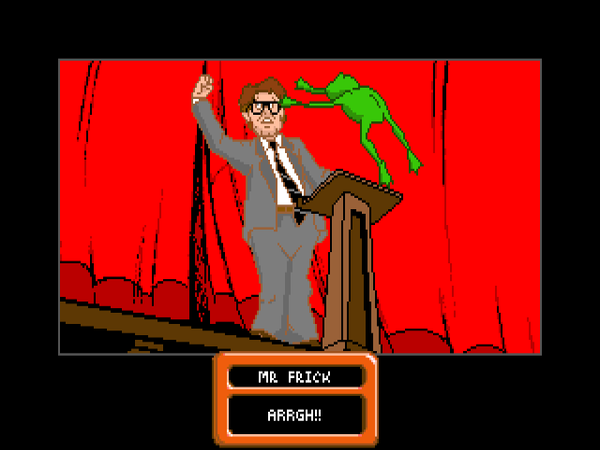

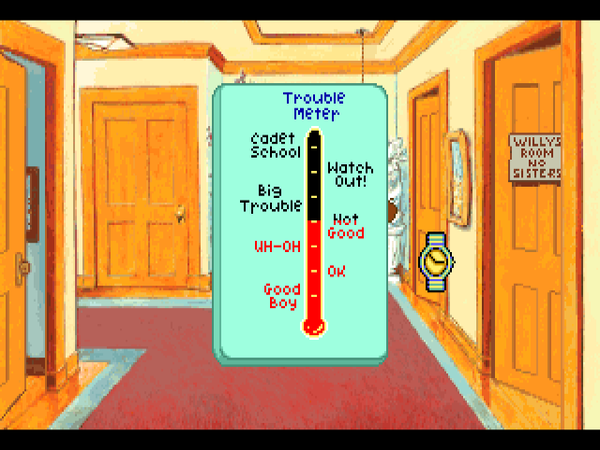

6. Getting into Weird Ed’s room in Maniac Mansion

By Ron Gilbert, Lucasfilm Games, 1987

How it works: In Ron Gilbert’s first adventure game, you control not one but three characters, a trio of teenage stereotypes who enter the creepy mansion of Dr. Fred one hot summer night. Each has a unique skill set, and each can move about the grounds independently. Far from being just a gimmick, this has a huge effect on the nature of the game’s puzzles. Instead of confining yourself to one room at a time, as in most adventure games, your thinking has to span the environment; you must coordinate the actions of characters located far apart. Couple this with real-time gameplay and an unusually responsive and dynamic environment, and the whole game starts to feel wonderfully amenable to player creativity, full of emergent possibilities.

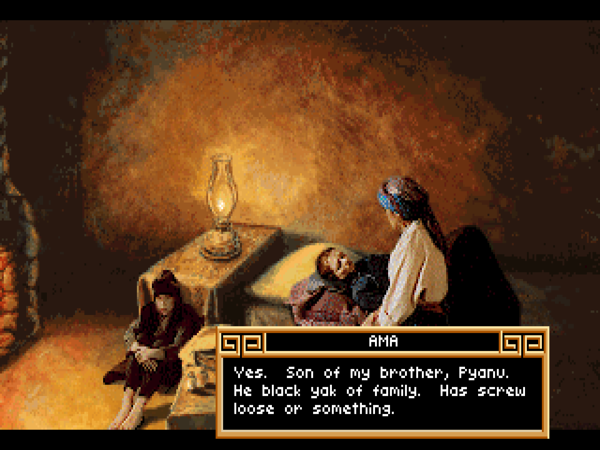

In this example of a Maniac Mansion puzzle, you need to search the bedroom of Weird Ed, the son of the mad scientist Fred and his bonkers wife Edna. If you enter while he’s in there, he’ll march you off to the house’s dungeon. Thus you have to find a way to get rid of him. In the sequence below, we’ve placed the kid named Dave in the room adjacent to Ed’s. Meanwhile Bernard is on the house’s front porch. (This being a comedy game, we won’t question how these two are actually communicating with each other.)

Why it works: As graphics fidelity increases in an adventure game, the possibility space tends to decrease. Graphics are, after all, expensive to create, and beautiful high-resolution graphics all the more expensive. By the late 1990s, the twilight of the traditional adventure game as more than a niche interest among gamers, the graphics would be very beautiful indeed, but the interactivity would often be distressingly arbitrary, with little to no implementation of anything beyond the One True Path through the game.

Maniac Mansion, by contrast, makes a strong argument for the value of primitive graphics. This game that was originally designed for the 8-bit Commodore 64 uses its crude bobble-headed imagery in the service of the most flexible and player-responsive adventure design Lucasfilm Games would ever publish over a long and storied history in graphic adventures. Situations like the one shown above feel like just that — situations with flexible solutions — rather than set-piece puzzles. You might never have to do any of the above if you take a different approach. (You could, for instance, find a way to befriend Weird Ed instead of tricking him…) The whole environmental simulation — and a simulation really is what it feels like — is of remarkable complexity, especially considering the primitive hardware on which it was implemented.

Our puzzling design lesson: Try thinking holistically instead of in terms of set-piece roadblocks, and try thinking of your game world as a responsive simulated environment for the player to wander in instead of as a mere container for your puzzles and story. You might be surprised at what’s possible, and your players might even discover emergent solutions to their problems which you never thought of.

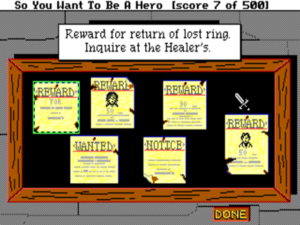

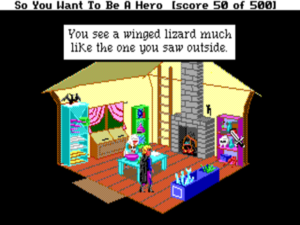

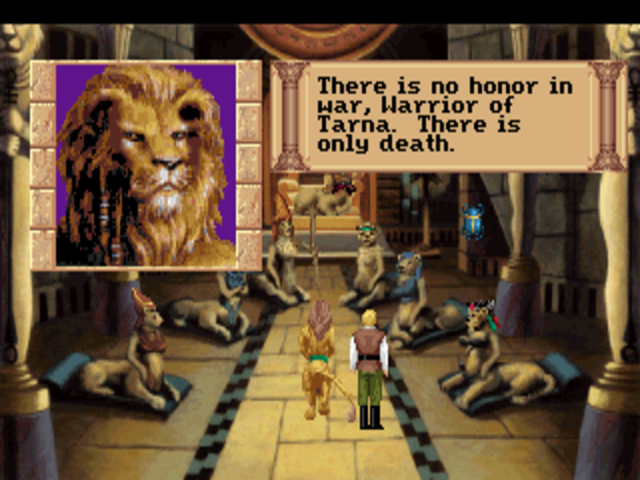

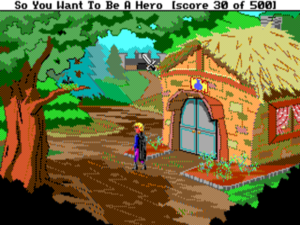

7. Getting the healer’s ring back in Hero’s Quest (later known as Quest for Glory I)

By Lori Ann and Corey Cole, Sierra, 1989

How it works: Hero’s Quest is another game which strains against the constrained norms in adventure-game design. Here you create and develop a character over the course of the game, CRPG-style. His statistics largely define what he can do, but your own choices define how those statistics develop. This symbiosis results in an experience which is truly yours. Virtually every puzzle in the game admits of multiple approaches, only some (or none) of which may be made possible by your character’s current abilities. The healer’s lost ring is a fine example of how this works in practice.

You go to inquire with the healer. Outside her hut is a tree, and on the tree is the nest of a sort of flying lizard.

I’ll reveal now that the ring is in the nest. But how to get at it? The answer will depend on the kind of character you’ve built up. If your “throwing” skill is sufficient, you can throw rocks at the nest to drive off the lizard and knock it off the tree. If your “magic” skill is sufficient and you’ve bought the “fetch” spell, you can cast it to bring the nest to you. Or, if your “climb” skill is sufficient, you can climb the tree. If you can’t yet manage any of this, you can continue to develop your character and come back later. Or not: the puzzle is completely optional. The healer rewards you only with six extra gold pieces and two healing potions, both of which you can earn through other means if necessary.

Why it works: This puzzle would be somewhat problematic if solving it was required to finish the game. Although several lateral nudges are provided that the ring is in the nest, it strikes me as dubious to absolutely demand that the player put all the pieces together — or, for that matter, to even demand that the player notice the nest, which is sitting there rather inconspicuously in the tree branch. Because solving the puzzle isn’t an absolute requirement, however, it becomes just another fun little thing to discover in a game that’s full of such generosity. Some players will notice the nest and become suspicious, and some won’t. Some players will find a way to see what’s in it, and some won’t. And those that do find a way will do so using disparate methods at different points in the game. Even more so than Maniac Mansion, Hero’s Quest gives you the flexibility to make your own story out of its raw materials. No two players will come away with quite the same memories.

This melding of CRPG mechanics with adventure-game elements is still an underexplored area in a genre which has tended to become less rather than more formally ambitious as it’s aged. (See also Origin’s brief-lived Worlds of Ultima series for an example of games which approach the question from the other direction — adding adventure-game elements to the CRPG rather than the other way around — with equally worthy results.) Anything adventures can do to break out of the static state-machine paradigm in favor of flexibility and dynamism is generally worth doing. It can be the difference between a dead museum exhibition and a living world.

Our puzzling design lesson: You can get away with pushing the boundaries of fairness in optional puzzles, which you can use to reward the hardcore without alienating your more casual players. (Also, go read Maniac Mansion‘s design lesson one more time.)

8. Blunting the smith’s sword in Loom

By Brian Moriarty, Lucasfilm Games, 1990

How it works: Games like Hero’s Quest succeed by being generously expansive, while others, like Loom, succeed by boiling themselves down to a bare essence. To accompany its simple storyline, which has the rarefied sparseness of allegory, Loom eliminates most of what we expect out of an adventure game. Bobbin Threadbare, the hero of the piece, can carry exactly one object with him: a “distaff,” which he can use to “spin” a variety of magical “drafts” out of notes by tapping them out on an onscreen musical staff. Gameplay revolves almost entirely around discovering new drafts and using them to solve puzzles.

The ancestor of Loom‘s drafts is the spell book the player added to in Infocom’s Enchanter series. There as well you cast spells to solve puzzles — and, in keeping with the “juicy” approach, also got to enjoy many amusing effects when you cast them in the wrong places. But, as we saw in our earlier explication of one of Enchanter‘s puzzles, you can’t always rely on your spell book in that game. In Loom, on the other hand, your distaff and your Book of Patterns — i.e., drafts — is all you have. And yet there’s a lot you can do with them, as the following will illustrate.

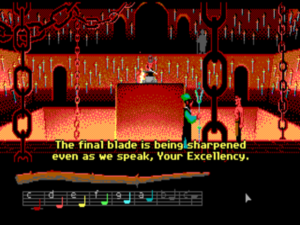

Bobbin eavesdrops from the gallery as Bishop Mandible discusses his plan for world domination with one of his lackeys. His chief smith is just sharpening the last of the swords that will be required. Bobbin has a pattern for “sharpen.” That’s obviously not what we want to do here, but maybe he could cast it in reverse…

Why it works: Loom‘s minimalist mechanics might seem to allow little scope for clever puzzle design. Yet, as this puzzle indicates, such isn’t the case at all. Indeed, there’s a certain interactive magic, found by no means only in adventure games, to the re-purposing of simple mechanics in clever new ways. Loom isn’t a difficult game, but it isn’t entirely trivial either. When the flash of inspiration comes that a draft might be cast backward, it’s as thrilling as the thrills that accompany any other puzzle on this list.

It’s also important to note the spirit of this puzzle, the way it’s of a piece with the mythic dignity of the game as a whole. One can’t help but be reminded of that famous passage from the Book of Isaiah: “And they shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

Our puzzling design lesson: Wonderful games can be and have been built around a single mechanic. If you’ve got a great one, don’t hesitate to milk it for all it’s worth. Also: puzzles can illuminate — or undermine — a game’s theme as well as any other of its aspects can.

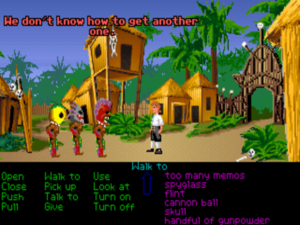

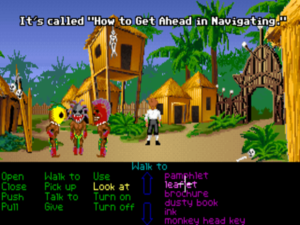

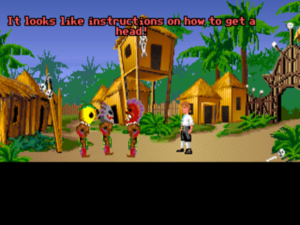

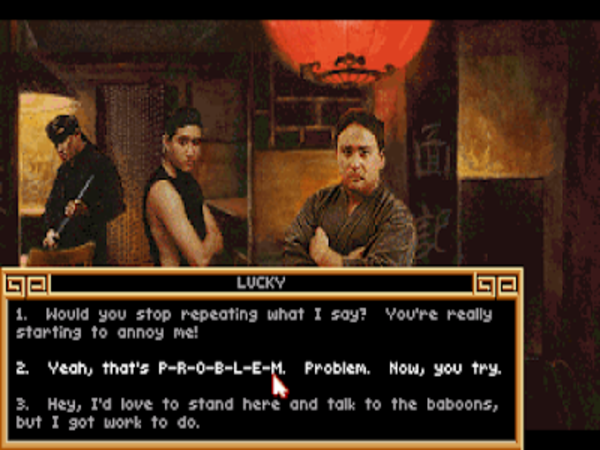

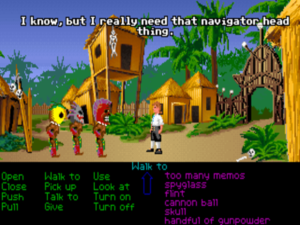

9. Teaching the cannibals how to get a head in The Secret of Monkey Island

By Ron Gilbert, Lucasfilm Games, 1990

How it works: For many of us, the first Monkey Island game is the Platonic ideal of a comedic graphic adventure: consistently inventive, painstakingly fair, endlessly good-natured, and really, truly funny. Given this, I could have chosen to feature any of a dozen or more of its puzzles here. But what I’ve chosen — yes, even over the beloved insult sword-fighting — is something that still makes me smile every time I think about it today, a quarter-century after I first played this game. Just how does a young and ambitious, up-and-coming sort of cannibal get a head?

Hapless hero Guybrush Threepwood needs the human head that the friendly local cannibals are carrying around with them.

Why it works: One might call this the graphic-adventure equivalent of the text-adventure puzzle that opened this list. More than that, though, this puzzle is pure Ron Gilbert at his best: dumb but smart, unpretentious and unaffected, effortlessly likable. When you look through your inventory, trying to figure out where you’re going to find a head on this accursed island, and come upon that useless old leaflet you’ve been toting around all this time, you can’t help but laugh out loud.

Our puzzling design lesson: A comedic adventure game should be, to state the obvious, funny. And the comedy should live as much in the puzzles as anywhere else.

10. Tracking down the pendant in The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes

By Eric Lindstrom and R.J. Berg, Electronic Arts, 1992

How it works: This interactive mystery, one of if not the finest game ever to feature Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary detective, is notable for its relative disinterest in the physical puzzles that are the typical adventure game’s stock in trade. Instead it has you collecting more abstract clues about means, motive, and opportunity, and piecing them together to reveal the complicated murder plot at the heart of the story.

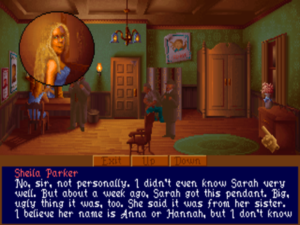

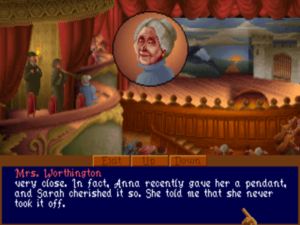

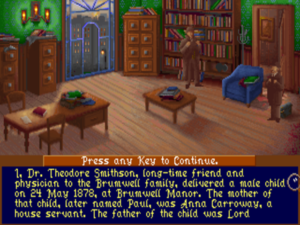

It all begins when Holmes and Watson get called to the scene of the murder of an actress named Sarah Carroway: a dark alley just outside the Regency Theatre, where she was a star performer. Was it a mugging gone bad? Was it the work of Jack the Ripper? Or was it something else? A mysterious pendant becomes one of the keys to the case…

We first learn about Sarah Carroway’s odd pendant when we interview her understudy at the theater. It was a recent gift from Sarah’s sister, and she had always worn it since receiving it. Yet it’s missing from her body.

We find the workplace of Sarah’s sister Anna. She’s also in show biz, a singer at the Chancery Opera House. The woman who shared a box with Sarah during Anna’s performances confirms the understudy’s story about the pendant. More ominously, we learn that Anna too has disappeared.

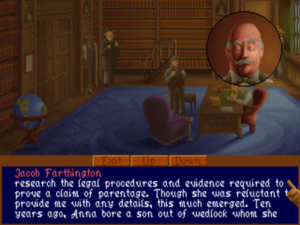

We track down Anna’s solicitor and surrogate father-figure, a kindly old chap named Jacob Farthington. He tells us that Anna bore a child to one Lord Brumwell some years ago, but was forced to give him up to Brumwell without revealing his parentage. Now, she’s been trying to assert her rights as the boy’s mother.

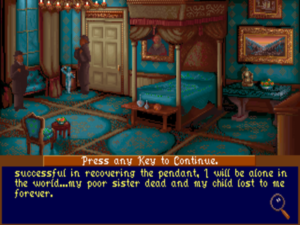

More sleuthing and a little bit of sneaking leads us at last to Anna’s bedroom. There we find her diary. It states that she’s hired a detective following Sarah’s murder — not, regrettably, Sherlock Holmes — to find out what became of the pendant. It seems that it contained something unbelievably important. “A humble sheet of foolscap, depending on what’s written upon it, can be more precious than diamonds,” muses Holmes.

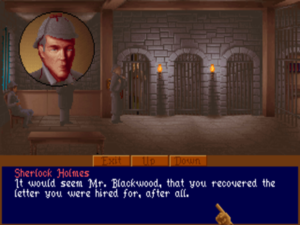

Yet more detecting on our part reveals that a rather dense blackguard named Blackwood pawned the pendant. Soon he confesses to Sarah’s murder: “I got overexcited. I sliced her to make her stop screaming.” He admits that he was hired to recover a letter by any means necessary by “an old gent, very high tone,” but he doesn’t know his name. (Lord Brumwell, perhaps?) It seems he killed the wrong Carroway — Anna rather than Sarah should have been his target — but blundered onto just the thing he was sent to recover anyway. But then, having no idea what the pendant contained, he pawned it to make a little extra dough out of the affair. Stupid is as stupid does…

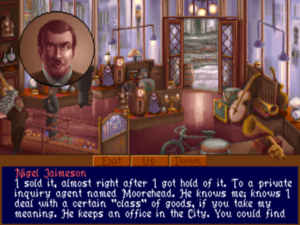

So where is the pendant — and the proof of parentage it must have contained — now? We visit the pawn shop where Blackwood unloaded it. The owner tells us that it was bought by an “inquiry agent” named Moorehead. Wait… there’s a Moorehead & Gardner Detective Agency listed in the directory. This must be the detective Anna hired! Unfortunately, we are the second to ask about the purchaser of the pendant. The first was a bit of “rough trade” named Robert Hunt.

We’re too late. Hunt has already killed Gardner, and we find him just as he’s pushing Moorehead in front of a train. We manage to nick Hunt after the deed is done, but he refuses to say who hired him or why — not that we don’t have a pretty strong suspicion by this point.

Luckily for our case, neither Gardner nor Moorehead had the pendant on him at the time of his death. We find it at last in their safe. Inside the pendant, as we suspected, is definitive proof of the boy’s parentage. Now we must pay an urgent visit to Lord Brumwell. Is Anna still alive, or has she already met the same fate as her sister? Will Brumwell go peacefully? We’ll have to play further to find out…

Why it works: Even most allegedly “serious” interactive mysteries are weirdly bifurcated affairs. The game pretty much solves the mystery for you as you jump through a bunch of unrelated hoops in the form of arbitrary object-oriented puzzles that often aren’t all that far removed from the comedic likes of Monkey Island. Even some pretty good Sherlock Holmes games, like Infocom’s Sherlock: The Riddle of the Crown Jewels, wind up falling into this trap partially or entirely. Yet The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes stands out for the way it really does ask you to think like a detective, making connections across its considerable length and breadth. While you could, I suppose, brute-force your way through even the multifaceted puzzle above by visiting all of the locations and showing everything to every suspect, it’s so much more satisfying to go back through Watson’s journal, to muse over what you’ve discovered so far, and to make these connections yourself. Lost Files refuses to take the easy way out, choosing instead to take your role as the great detective seriously. For that, it can only be applauded.

Our puzzling design lesson: Graham Nelson once indelibly described an adventure game as “a narrative at war with a crossword.” I would say in response that it really need not be that way. A game need not be a story with puzzles grafted on; the two can harmonize. If you’re making an interactive mystery, in other words, don’t force your player to fiddle with sliding blocks while the plot rolls along without any other sort of input from her; let your player actually, you know, solve a mystery.

(Once again, my thanks to Casey Muratori for suggesting this article. And thank you to Mike Taylor and Alex Freeman for suggesting some of the featured puzzles.)