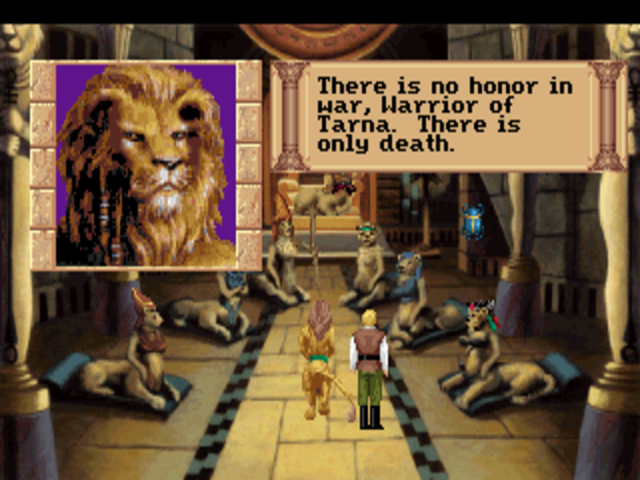

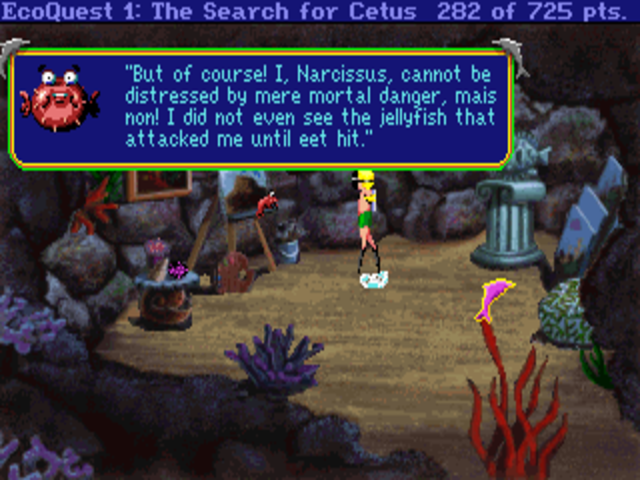

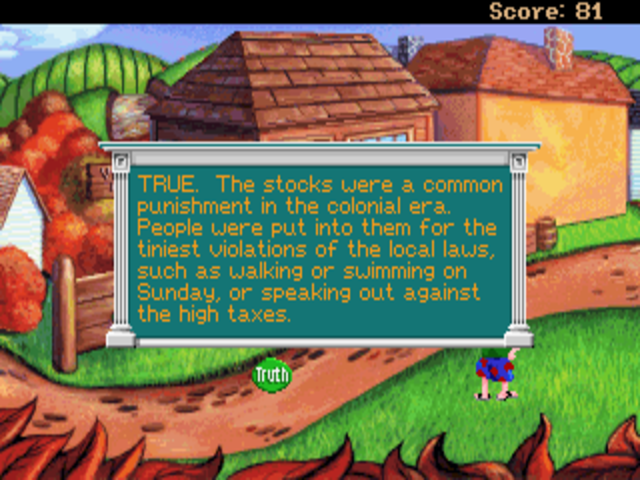

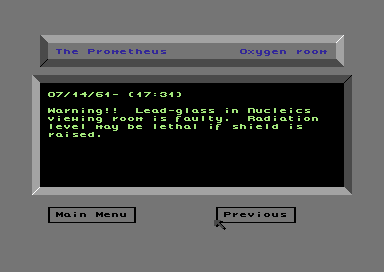

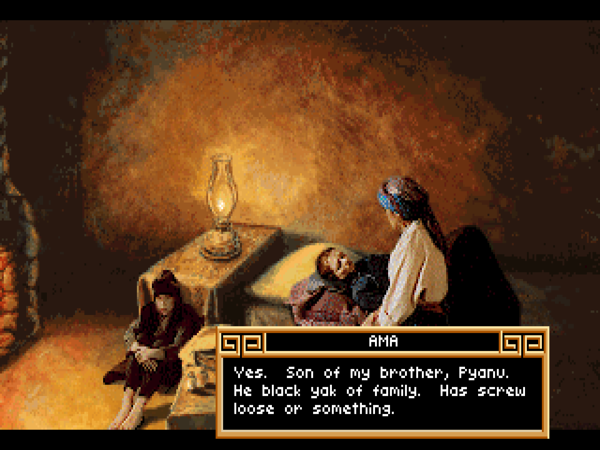

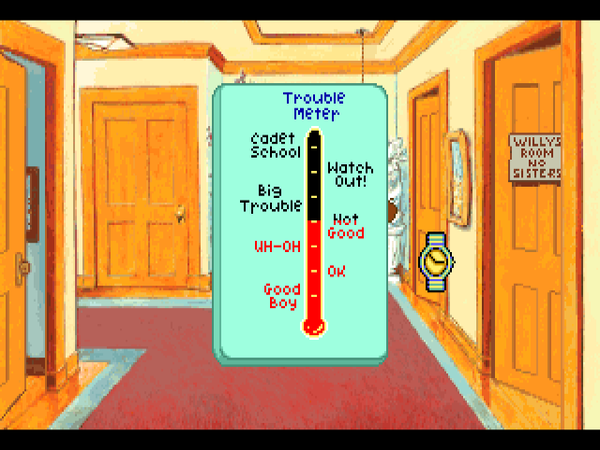

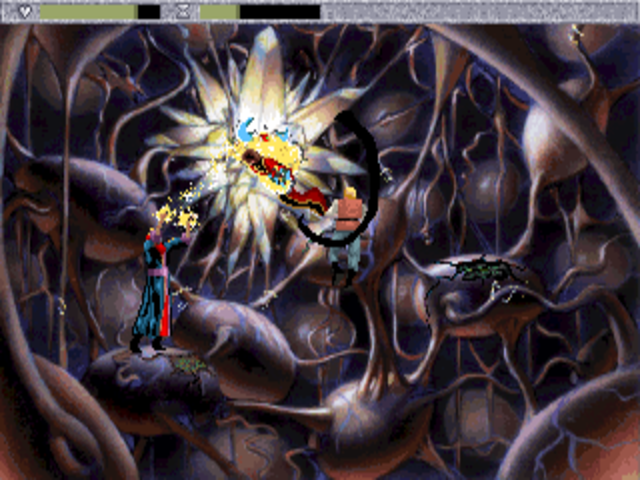

The VGA remake of Quest for Glory I. By this point, Sierra’s graphics exceeded the quality of most Saturday-morning cartoons, and weren’t far off the standard set by feature films, being held back more by the technical limitations of VGA graphics than those of the artists doing the drawing.

Quest for Glory, Lori Ann and Corey Cole’s much-loved series of adventure/CRPG hybrids, took a year off after its second installment, while each half of the couple designed an educational game for Sierra’s Discovery Series. After finishing her Discovery game Mixed-Up Fairy Tales, a less ambitious effort aimed at younger children than Corey’s The Castle of Dr. Brain, Lori headed a remake of the first Quest for Glory, using VGA graphics and a point-and-click interface in place of EGA and a parser. While opinions vary as to the remake’s overall worthiness — I’m personally fonder of the original version, as is Corey Cole — no one could deny that it looked beautiful in 256 colors. Sierra was, like many other media producers at the time, operating in a short-lived intermediate phase between analog and fully-digital production techniques, which gave the work a look unique to this very specific period. For example, most of the characters in the Quest for Glory I remake were first sculpted in clay by art director Arturo Sinclair, then digitized and imported into the game. One can only hope that contemporary gamers took the time to appreciate the earthy craftsmanship of his work. Sierra and much of their industry would soon fall down the full-motion video rabbit hole, and the 3D Revolution as well was just over the horizon, poised to offer all sorts of exciting new experiential possibilities but also to lose almost as much in the way of aesthetic values. It would, in other words, be a long time before games would look this good again.

Thankfully, the era of hand-drawn — or hand-sculpted — art at Sierra would last long enough to carry through the next two Quest for Glory games as well. Much else, though, would conspire against them, and in my opinion neither the third nor the fourth game is as strong as either of the first two. Today we’ll have a look at these later efforts’ strengths and failings and the circumstances that led to each.

Well before starting work on the very first Quest for Glory, Lori Ann Cole had sketched out a four-game plan for the series as a whole. It would see the player’s evolving hero visiting four different cultural regions of a fantasy world, all drawn from cultures of our own world, in adventures where the stakes would get steadily higher. The first two games had thus covered medieval Germany and the Arab world, and the last two were slated to go to the murky environs of Eastern Europe and the blazing sunshine of mythic Greece. In fact, Quest for Glory II ends with an advertisement of sorts for the “upcoming” Quest for Glory III: Shadows of Darkness, the Eastern European game. Yet almost as soon as the second game was out the door, the Coles started to have misgivings. To go with its milieu drawn from Romanian and Slavic folklore and the Gothic-horror tradition, Shadows of Darkness was to have a more unfriendly, foreboding approach to gameplay as well. The Coles planned to make “aloneness, suspicion, and paranoia,” as Corey puts it, the hallmarks of the game. They didn’t want to abandon that uncompromising vision, but neither were they sure that their players were ready for it.

Shortly before leaving Sierra to join Origin Systems, staff writer Ellen Guon suggested that the third game could easily be set in Africa instead, following up on an anecdote mentioned by one of the characters in passing in Quest for Glory II — thus extending the series’s arc from four to five games and postponing the “dark” entry until a little later. The Coles loved the idea, and Quest for Glory III: The Wages of War was born. Sure, making it did interfere with some of the thematic unities Lori had built into the series; its entries had been planned to correspond with the four classical elements of Earth, Fire, Air, and Water, as well as the four cardinal compass directions and the four seasons. But perhaps that was all a little too matchy-matchy anyway…

Other, less welcome changes were also in the offing: the new game’s gestation was immediately impacted by the removal of Corey Cole from most of the process. Corey had originally been hired by Sierra in a strictly technical role — specifically, for his expertise in programming the Atari ST and the Motorola 68000 CPU at its heart. His first assigned task had been to help port Sierra’s then-new SCI game engine to that platform, and he was still regarded around the office as the resident 68000 expert. Thus when Sierra head Ken Williams cooked up a scheme to bring their games to the Sega Genesis, a videogame console that with an optional CD-ROM accessory was also built around the 68000, it was to Corey that he turned. So, while Lori worked on Quest for Glory III alone, Corey struggled with what turned out to be an impossible task. The Genesis’s memory was woefully inadequate, and its graphics were limited to 64 colors from a palette of 512, as opposed to the 256 colors from a palette of 262,144 of the VGA graphics standard for which Sierra’s latest computer games were coded. Wiser heads finally prevailed and the whole endeavor was cancelled, freeing up Corey to reform his design partnership with Lori.

This happened, however, only in the final stages of Quest for Glory III‘s development. Among fans today, this game is generally considered the weakest link in the series, and the absence of Corey Cole is often cited as a primary reason. I’ll return to the impact his absence may have had, but first I’d like to mention what the game undeniably does right: the setting.

It’s often forgotten that Egypt, that birthplace of so much of human civilization, is a part of Africa; this essential fact, though, Lori Ann Cole didn’t neglect. The western part of the game’s map, where you begin, feels like an outlying outpost of Egyptian culture, complete with the pyramids and other monumental architecture we know from our history books. As you travel eastward, the savanna turns into jungle, and the societies you meet there become reflections of tribal Africa. It’s all drawn — both metaphorically, through the writing, and literally, through the graphics — with considerable charm and skill. Sub-Saharan Africa in particular isn’t a region we see depicted very often in games, and still less often with this degree of sympathy. As I noted in my first article on the Quest for Glory series, there’s a travelogue quality that runs through its entirety, showing us our own world’s many great and varied cultures through the lens of these fantasy adventures. The third game, suffice to say, upholds that tradition admirably.

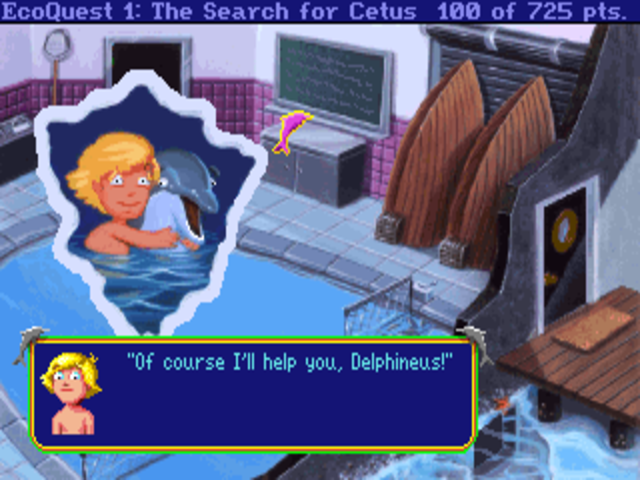

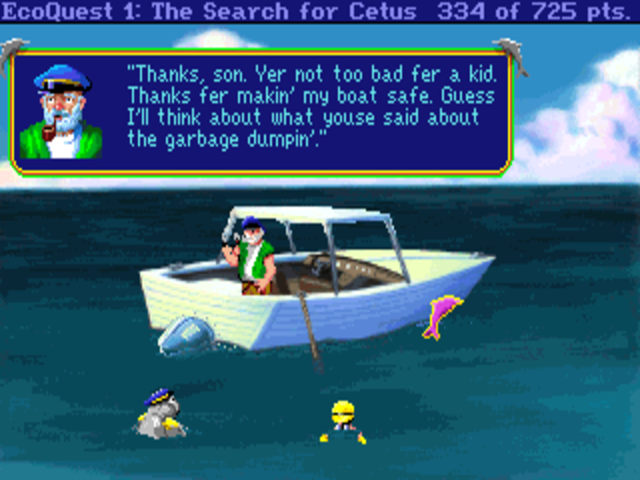

Also welcome is the theme of the game. In contrast to most computer games, this one has you trying to prevent a war rather than win one. The aforementioned Egyptian and tribal African cultures have been set at odds by a combination of prejudices, misunderstandings, and — this being a fantasy game and all — the odd evil wizard. It’s up to you to play the peacemaker. “You start getting a better and better idea of just how senseless war is,” says Corey, “and how everybody loses by it.” Of course, there’s a certain cognitive dissonance about an allegedly anti-war game in which you spend so much of your time mowing down monsters by decidedly violent means, but props for effort.

In fact, any criticism of Quest for Glory should be tempered by the understanding that what the Coles did with this series was quite literally unprecedented, and, further, that no one else has ever tried to do anything quite like it since. While plenty of vintage CRPGs, dating all the way back to Wizardry, allowed you to move your characters from game to game, the Quest for Glory series is a far more complex take on a role-playing game than those simple monster bashers, with character attributes affecting far more aspects of the experience than combat alone — even extending into a moral dimension via a character’s “honor” attribute and the associated possibility to change to the prestige class of Paladin. It must have been tempting indeed to throw out the past and force players to start over with new characters each time the Coles started working on the next game in the series, but they doggedly stuck to their original vision of four — no, make that five — interlinked games that could all feature the very same custom hero, assuming the player was up to the task of buying and playing all of them.

But, fundamental to the Coles’ conception of their series though it was, this approach did have its drawbacks, which were starting to become clear by the time of Quest for Glory III. Corey Cole himself has admitted that “the play balance — both pacing and combat difficulty — and of course the freshness of the concept were strongest in Quest for Glory I.” Certainly that’s the entry in this hybrid series that works best as a CRPG, providing that addictive thrill of seeing your character slowly getting stronger, able to tackle monsters and challenges he couldn’t have dreamed of in the beginning. The later games are hampered by the well-known sense of diminishing returns that afflicts so many RPGs at higher levels; it’s much more fun in tabletop Dungeons & Dragons as well to advance from level 1 to level 8 than it is from level 8 to level 16. Even when you find that you need to spend time training in order to meet some arbitrary threshold — more on that momentarily — your character in the later Quest for Glory games never really feels like he’s going anywhere. The end result is to sharply reduce the importance of the most unique aspect of the series as it wears on. For this player anyway, that also reduces a big chunk of the series’s overall appeal. I haven’t tried it, but I suspect that these games may actually be more satisfying to play if you don’t import your old character into each new one, but rather start out fresh each time with a weaker hero and enjoy the thrill of building him up.

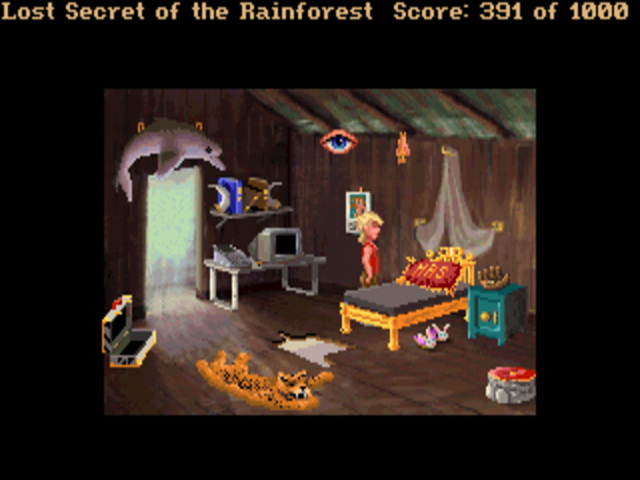

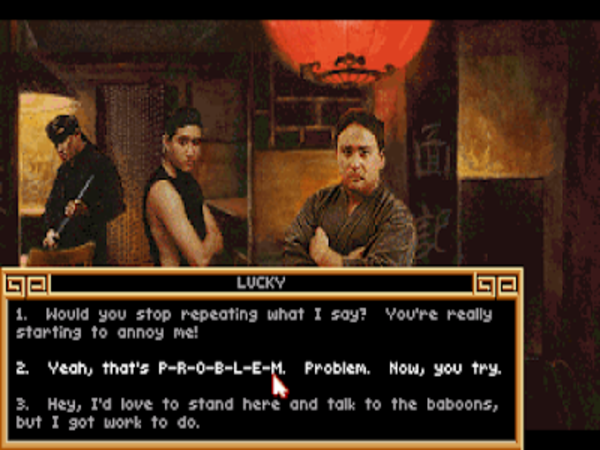

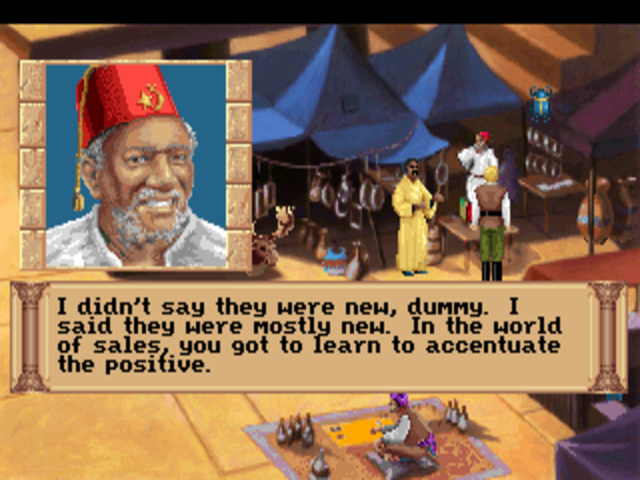

Sanford and Son make an appearance.

Quest for Glory III also disappoints in other ways.The first two games had been loaded with alternative solutions and approaches of all stripes, full of countless secrets and Easter eggs. Quest for Glory III is far less generous on all of these fronts. There just isn’t as much to do and discover outside the bounds of those things that are absolutely necessary to advance the plot. And one of the three possible character classes you can play, the Thief, has markedly fewer interesting things to do than the others even in the course of doing that much. The whole game feels less accommodating and rewarding — less amenable to your personal choices, one might say — than what came before. It plays, in other words, more like just another Sierra adventure game and less like the uniquely rich and flexible experience the first two games are.

This lack of design ambition can to some degree be attributed to the absence of Corey Cole for most of the design process. Corey was generally the “puzzle guy” in the partnership, dealing with all the questions of smaller-scale interactivity, while Lori was the “story gal,” responsible for the wide-angle plotting. And indeed, when I asked Corey about his own impressions of the game in relation to its predecessors, he acknowledged that “certainly Quest for Glory III is lighter on puzzles, while having just as much story as Quest for Glory II.”

Yet Corey’s absence isn’t the only reason that the personality of the series began to morph with this third installment. The most obvious change between the second and third game — blindingly obvious to anyone who plays them back to back — is the move from a parser-based to a pure point-and-click interface. I trust that I don’t need to belabor how this could remove some of the scope for player creativity, and especially what it might mean for the many little secrets for which the first two games are so known. I’m no absolute parser purist — my opinion has always been that the best interface for any given game is entirely contextual, based upon the type of experience the designer is trying to create — but I can’t help but feel that Quest for Glory lost something when it dumped the parser.

One issue with Quest for Glory III that may actually be a subtle, inadvertent byproduct of the switch to point-and-click is a certain aimlessness that seems baked into the design. Too much of the story is predicated on unmotivated wandering over a map that’s not at all suited to more methodical exploration.

I hate the Quest for Glory III overland map with a passion. Unique locations aren’t signaled on it, but it’s nevertheless vital that you thoroughly explore it, meaning you’re forced to click on any formation that looks interesting in the hope that it’s more than decorative, a process which disappoints and frustrates more often than not. And while you’re wandering around in this random fashion, you’re constantly being attacked by uninteresting monsters and being forced to engage in tedious combat. Note that what you see above is only the first of several screens full of this sort of thing.

When I played Quest for Glory III, I eventually wound up in that dreaded place known to every adventure player: where you’ve exhausted all your leads and are left with no idea what the game expects from you next. This was, however, a feeling new to me in the course of playing this particular series. When I turned with great reluctance to a walkthrough — I’d solved the first two games entirely on my own — I learned that I was expected to train my skills up to a certain level in order shake the plot back into gear.

But how, you ask, can such problems be traced back to the loss of the parser? Well, Corey has mentioned how Lori — later, he and Lori — attempted to restore some of the sense of spontaneity and surprise that had perhaps been lost alongside the parser through the use of “events”: “Instead of each game scene having one specific thing that happens in it, our scenes change throughout the game. Sometimes the passage of time triggers a new event, and sometimes it’s the result of the ripple effect of player actions. It was supposed to feel organic.” When this approach works well, it works wonderfully well in providing a dynamic environment that seems to unfold spontaneously from the player’s perspective, just the way a good interactive story should. That’s the best-case scenario. The worst case is when you haven’t done whatever arbitrary action is needed to get a vital event to fire, and you’re left to wander around wondering what’s next. Finally, when you peek at a walkthrough, the mechanisms behind it all are revealed in the ugliest, most mimesis-annihilating way imaginable. I understand what Quest for Glory III wants to do, and I wholeheartedly approve. But there needed to be more work done to avoid dead spots — whether in the form of more possible triggers or just of more nudges to tell the player what the game expects from her — or, ideally, both.

Another odd Quest for Glory tradition was to give each game in the series a new combat system. Quest for Glory III tried to add a bit more strategy to the affair with buttons for “swing,” “dodge,” “thrust,” and “parry,” but in my experience at least simply mashing down the swing button works as well as anything else. Thus another Quest for Glory tradition: that of none of these multifarious combat systems ever being completely satisfying.

Still, whatever the game’s failings, few players or reviewers in its own time seemed to notice. Upon its release in September of 1992 — just four months after the Quest for Glory I remake — Quest for Glory III was greeted with solid sales and positive reviews, a reception which stands in contrast to its contemporary reputation as the weakest link in the series. With this affirmation of their efforts and with Corey now free of distractions, the Coles plunged right into the fourth game. Quest for Glory IV would prove the most ambitious and the most difficult entry in the series — and, in my opinion anyway, its greatest waste of potential.

The game officially known simply as Quest for Glory: Shadows of Darkness — Sierra inexplicably dropped the Roman numeral this time and this time only — is indeed often spoken of as the “dark” entry of the series, but that claim strikes me as, at most, relative. My skepticism begins with the unbelievably cheesy subtitle, which put my wife right off the game before she saw more than the title screen. (“Someone should tell those people that darkness doesn’t make shadows…”) Banal subtitles, perhaps (hopefully?) delivered with an implied wink and nudge, had become something of a series trademark by this point — Trial by Fire? The Wages of War? Cliché much? — but this was taking things to a whole other level.

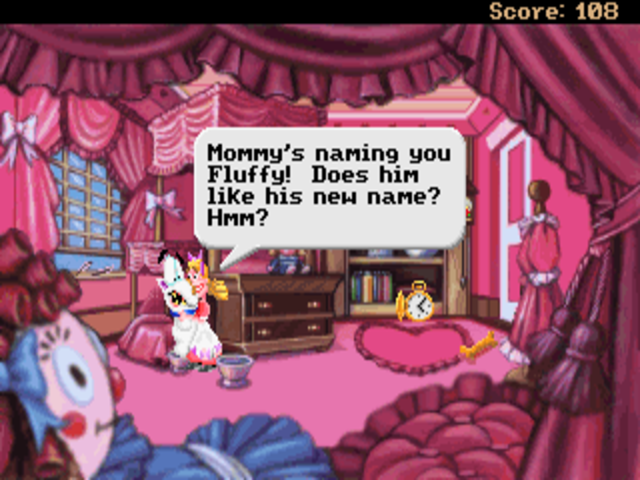

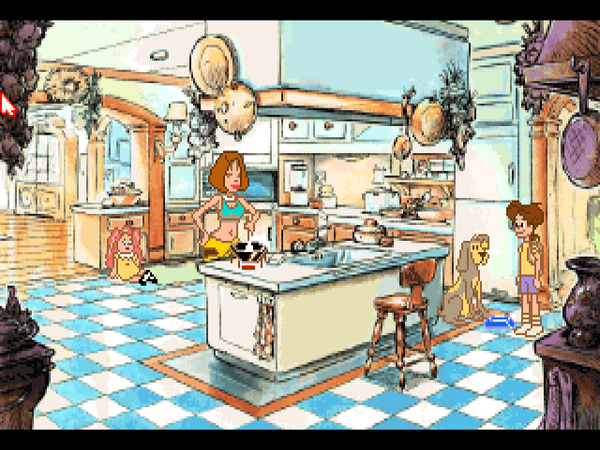

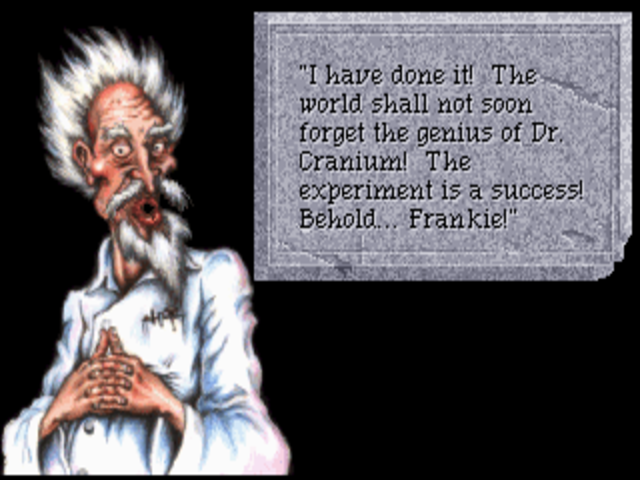

Dr. Brain fans will presumably be pleased to meet his alter ego Dr. Cranium in Quest for Glory IV. (Frankie, for the record, is a female Frankenstein whose “assets” Dr. Cranium very much approves of.)

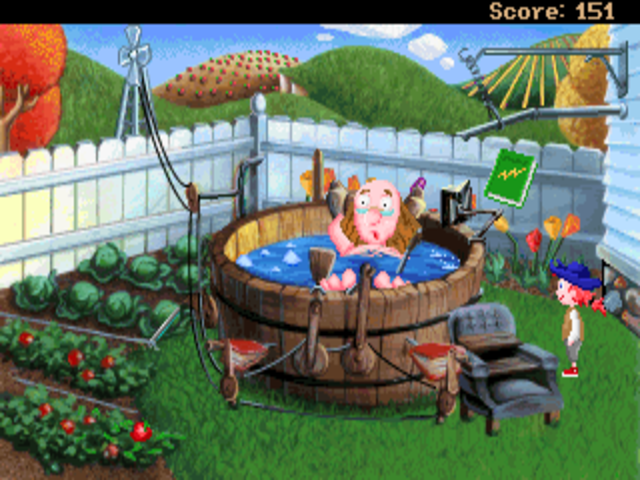

To speak more substantively (or at least less snarkily), the “dark” aspects of the game come to the fore intermittently at best. I’ve played games which I’ve found genuinely scary; this is not one of them. It certainly includes plenty of horror tropes, but it’s difficult to take any of it all that seriously. This is a game that features Dr. Brain channeling Dr. Frankenstein. It’s a game where you fight a killer rabbit lifted out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail. It’s a game where you win the final battle against the evil wizard by telling him the Ultimate Joke and taking advantage when he collapses into laughter. From the Boris Karloff imitator guarding the gates to the villain’s castle to Igor the hunchbacked gravedigger, this is strictly B-movie horror — or, perhaps better said, a parody of B-movie horror. It’s hard to imagine anyone losing sleep over this game.

In fact, I was so nonplussed by its popularly accepted “dark” label that I asked Corey what he thought about it, and was gratified to find that he at least partially agreed with me:

Maybe a better word would be “unforgiving.” A Quest for Glory III theme is friendship and the need to work together with others. In Quest for Glory IV, we turned that around 180 degrees. The player would start out on his own, mistrusted by everyone. Through the course of the game, he will gradually win people’s trust and once again have allies by the end. This is not an easy theme for players new to the series to handle.

Lori Ann Cole elaborated on the same idea in a contemporary interview:

You’ll be very much alone [in Quest for Glory IV]. In Trial by Fire, you had a lot of friends to help you. You always had a place to go back to rest. You always had a place of safety until the very end of the game. Once you get into Shadows of Darkness, you’re not going to have any sanctuary. You won’t be able to trust anyone because nobody will trust you.

It’s true that a few subplots here strain toward a gravitas unlike anything else the Coles have ever attempted. In particular, the vampire named Katrina can be singled out as a villain who isn’t just Evil for the sake of it. She’s kidnapped a little girl from the village that is your center of operations, and one of your quests is to rescue her. In the course of doing so, you learn that the kidnapping was motivated by Katrina’s desperate, very human desire for family and companionship in her isolated castle. You end up killing her, of course, but her story is often praised — justifiably on the whole, if sometimes a bit too effusively — as a benchmark for intelligent characterization in games.

Structurally, Quest for Glory IV is most reminiscent of the first game in the series. You arrive in the village of Mordavia, part of a region that goes by the same name, which has been plagued of late by vampires, ghosts, mad scientists, and most of the other inhabitants of the Hammer Horror oeuvre. As you solve the villagers’ considerable collection of problems one by one, they go from being spit-in-your-food hostile to lauding you as the greatest hero in the land. In the best tradition of the series, and in contrast to some of the most commonly voiced complaints about Quest for Glory III, much of the game is nonlinear, and some of it is entirely optional.

The combat system in Quest for Glory IV owes a lot to the Street Fighter franchise of standup-arcade, console, and computer games, which were among the most popular of the era. Corey Cole considers it the best combat engine in the history of the series; opinions among fans are more divided. For those not interested in street-fighting their way through a Quest for Glory game, the Coles did make it possible for the first time to turn on an auto-combat mode.

Sadly, though, the game is nowhere near as playable as Quest for Glory I, II, or to some extent even III. This fault arises not from doing too little but rather from attempting to do too much. At the risk of being accused of psychoanalyzing its designers, I will note that the Coles had clearly been psyching themselves up to make this game for a long time — that, even as it was being pushed back to make room for Quest for Glory III, it had long since come to loom over their conception of the series as the Big Statement. Even when they were giving interviews to promote the finished Quest for Glory III, the conversation would keep drifting into their plans for the fourth game. “It will be a very intense game to design,” said Corey in one of those interviews, a comment that could be taken to reflect either excitement or trepidation — or, more likely, both. This was to be the place where the series departed from being easygoing light fantasy to become something more challenging, both thematically and in terms of its puzzles and other mechanics.

So, they just kept cramming more and more stuff into it. The setting doesn’t have the laser focus of the earlier games in the series, all of which portrayed fairly faithfully the myths and legends of a very specific real-world culture. Quest for Glory IV, despite including some monsters drawn from real Eastern European folklore, is more interested in Western pop culture’s idea of Transylvania than any real place — a land of shadows and creatures that go bump in the night and “I vant to bite yer neck.” Then, because the parade of Gothic-horror clichés apparently wasn’t enough, the Coles added H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos to the mix (or, as the manual calls him, “P.H. Craftlove”). The two make decidedly uneasy bedfellows. Gothic horror, as expressed best in Bram Stoker’s ultimate Gothic novel Dracula, takes place, explicitly or implicitly, in an essentially moral universe drawing heavily from Christianity, in which Good and Evil, God and the Devil, are real entities at war with one another, thus setting up the narratives of sin and redemption which predominate. Lovecraftian horror, on the other hand, posits an utterly uncaring, amoral universe, in which Good and Evil are meaningless concepts, mere ephemera of the deluded human imagination. To combine the two in one work of fiction is… problematic.

For all that one has to wonder whether any fans of this heretofore genial series were truly saying to themselves, “You know, what these games really need to be is harder,” the Coles’ determination to make this entry more difficult than its predecessors isn’t invalid in itself. In trying to make their harder game, however, they sometimes fall into the all too typical trap of making a game that’s not so much more difficult as less fair. The CRPG aspects are yet further de-emphasized in favor of more puzzles, some of which push the bounds of realistic solubility. And, for the first time in the series’s history, there are irrecoverable dead ends to wander into scattered across the design, along with other situations that seem like dead ends. The latter arise because the design once again relies heavily on “events” that the player triggers without being aware how she does so — and, once again, this isn’t a bad thing at all in theory, but in practice it’s too easy to get stuck in a cul de sac with no idea how to prod the plotting machinery into motion again.

Greatly exacerbating all of these issues — indeed, virtually indistinguishable from them, given that it’s often unclear which design infelicities are intentional and which are not — are all the bugs. Even today, when patch after patch has been applied, the game remains a terrifyingly unstable edifice. If your (emulated?) machine runs just a little bit too slow or too fast, it will crash at random points with a cryptic “Error 47” or “Error 52.” But far worse are the hidden bugs that can ruin your game while letting you play on for hours without realizing anything is wrong. The most well-known of these involves a vital letter that’s supposed to show up at your hotel, but that, for reasons that are still imperfectly understood even after all these years, sometimes fails to do so. If you’re unfortunate enough to have this happen to you, it will only be much, much later, when you can’t figure out what to do next and finally turn to a walkthrough, that you realize you have to all but start over from scratch.

In my experience, an adventure game must establish a bond of trust with its player to be enjoyable. My dominant emotion when playing Quest for Glory IV, however, was just the opposite. I mistrusted the design, and mistrusted the implementation of the design even more, asking myself at every turn whether I’d broken anything, whether this latest problem I was having was a legitimate puzzle or a bug. When you have to meta-game your way through a game, relying on FAQs and walkthrough to tiptoe around all its pitfalls, it’s awfully hard to engage with the story and atmosphere.

Still, I can be thankful that I first played Quest for Glory IV a quarter-century after its original release, after all those patches had already been applied. The game that shipped on December 31, 1993, was in a truly unconscionable, very probably unwinnable condition. This wasn’t, I should emphasize, the fault of the Coles, who would have given anything to have a few more months with their baby. But Sierra was having an ugly year financially, and decided that the game simply had to be released before the year was out for accounting reasons, come what may. If there was any justice in the world, they would have been rewarded with a class-action lawsuit for knowingly selling a product that was not just flawed but outright broken. To give you a taste of what gamers unwise enough to buy Quest for Glory IV in its original incarnation got to go through, I’d like to quote at some length from the review by Scorpia, Computer Gaming World magazine’s regular adventure columnist.

My difficulties began after the game was installed and it simply refused to run, period. A call to the Sierra tech line revealed that Shadows of Darkness, as released, was not compatible with the AMI BIOS (not exactly an obscure one). This was related to the special 32-bit protected mode under which the software operates. Fortunately, a patch was available, and I quickly got it online.

After the patch was applied, the game finally came up. Unfortunately, it came up silent. The 32-bit protected mode grabs all of upper memory for itself, so nothing can be loaded high, and a bare-bones DOS boot disk is necessary. This made it impossible to load in the Gravis Ultrasound Roland emulator, and I found that with the Sound Blaster emulator loaded low, the game again wouldn’t run. So, I had to play with no sound or music, which explains why there is no commentary on either.

I ran from a boot disk without sound, and for a while everything was fine. However, the further into the game, the slower it was in saving and restoring. Actual disk access was quite speedy, but waiting for the software to make up its mind to go to disk took a long time, often a minute or more. Some online folk complained of waiting three minutes or longer to restore a saved game. It was usually faster to quit the game, rerun it, and then restore a position. For saving, of course, you just had to wait it out.

Regardless of the frustrations, I got through the game [playing as] a Paladin and a Mage, and then moved on to the Thief. Three quarters of the way along, the game crashed in the swamp whenever I tried to open the Mad Monk’s tomb. This turned out to be a “random error” that might or might not show up. It hadn’t done so with the other two heroes, but this time it reared its ugly head.

Well, Sierra had a patch that fixed both this problem and the interminable waits for saves and restores (this patch, by the way, came out some time after the first one I had gotten). There was only one drawback: because of the extensive changes made to the files, my saved games were no good and I had to start over again from the beginning.

So, I started my Thief over. By day 11 in the game, all the quests had been finished, the five rituals collected, and it was just a matter of waiting for a certain note to appear in my room one morning (this note initiates the end of the game). On day 26, I was still waiting for it. Nothing could make it appear, even replaying from some earlier positions. Either the trigger for this event was not set, or somehow it was turned off. I had no way of knowing, and, with that in mind, I had no inclination to start from scratch again. This also happened to other players who were running characters other than Thieves, and we all eventually abandoned those games.

A way around the dead-end problem was worked out by Sierra. The key is spending enough nights in your room at the inn to hear several “voice dreams,” and, most importantly, hearing the weeping from the innkeeper’s room one midnight (you are awakened by this; don’t stay up waiting for it). These events must happen before you rescue Tanya.

Once those situations have occurred, it should be safe to rescue the girl. I tried this in my Thief game, and after spending two extra nights in my room, the problem was cleared up and I finished the game with the Thief. So, if you have been waiting around for that note, and it hasn’t shown, follow the above procedure and you should be able to continue on with the game.

Scorpia’s last two paragraphs in particular illustrate what I mean when I say that you can’t really hope to play Quest for Glory IV so much as meta-game your way through it with the aid of walkthroughs. She was extremely lucky to have been among the minority with online access at the time of the game’s release, and thus able to download patches and discuss the game’s multiple points of entrapment with other players. Most would only have been able to plead with Sierra’s support personnel and hope for a disk to arrive in the mail a week or two later.

What ought to have been the exciting climactic battle of Quest for Glory IV was so buggy in the original release that the game was literally impossible to complete. It’s remained one of the worst problem spots over the years since, requiring multiple FAQ consultations to tiptoe through all the potential problems. Have I mentioned how exhausting and disheartening it is to be forced to play this way?

Some months after the bug-ridden floppy-based release, Sierra published Quest for Glory IV on CD-ROM, in a version that tried to clean up the bugs and that added voice acting. It accomplished the former task imperfectly; as already noted, plenty of glitches still remain even in the version available for digital download today, not least among them the mystery of the never-appearing letter. The latter task, however, it accomplished superlatively. In a welcome departure from the atrocious voice acting found in their earliest CD-ROM products, Sierra put together a team of top-flight acting professionals, headed by the dulcet Shakespearian tones of John Rhys-Davies — a veteran character actor of many decades’ standing who’s best known today as Gimli the dwarf in Peter Jackson’s Lords of the Rings films — as the narrator and master of ceremonies. Rhys-Davies, who had apparently signed the contract in anticipation of a quick-and-easy payday, was shocked at the sheer volume of text he was expected to voice, and took to calling the game “the CD-ROM from hell” after spending days on end in the studio. But he persevered. Indeed, he and the other actors quite clearly had more than a little fun with it. The bickering inhabitants of the Mordavia Inn are a particular delight. These voice actors obviously take their roles with no seriousness whatsoever, preferring to wander off-script into broad semi-improvised impersonations of Jack Nicholson, Clint Eastwood, and Rodney Dangerfield. Would you think less of me if I admitted that they’re my favorite part of the game?

Of course, one could argue that Sierra’s decision to devote so many resources to this multimedia window dressing, while still leaving so many fundamental problems to fester in the core game, is a sad illustration of their misplaced priorities in this new age of CD-ROM-based gaming. The full story of just what the hell was going on inside Sierra at this point, leading to this imperfect and premature Quest for Glory IV as well as even worse disasters like their infamously half-finished 1994 release Outpost, is an important one that needs to be told, but one best reserved for a later article of its own.

For now, suffice to say that Quest for Glory IV was made to suffer for its failings, with a number of outright bad reviews in a gaming press that generally tended to publish very little of that sort of thing, and with far worse word of mouth among ordinary gamers. For a long time, its poor reception seemed to have stopped the series in its tracks, one game short of Lori Ann Cole’s long-planned climax. When a transformed Sierra, under new owners with new priorities, finally allowed that fifth and final game to be made years later, it would strike the series’s remaining fans as a minor miracle, even as the technology it employed was miles away from the trusty old SCI engine that had powered the series’s first four entries.

The critical consensuses on Quest for Glory III and IV have neatly changed places in the years since that last entry in the series was published. The third game was widely lauded back in the day, the fourth about as widely panned as the timid gaming press ever dared. But today, it’s the third game that is widely considered to be the series’s weakest link, while the fourth is frequently called the very best of them all. As someone who finds them both to be more or less flawed creations in comparison to what came before, I don’t really have a dog in this fight. Nevertheless, I do find this case of switched places intriguing. I think it says something about the way that so many play games — especially adventure games — today: with FAQ and walkthrough at the ready for the first sign of trouble. There’s of course nothing wrong with choosing to play this way; I’ve gone on record many times saying there is no universally right or wrong way to play any game, only those ways which are more or less fun for you. And certainly the fact that you can now buy the entire Quest for Glory series for less than $10 — much less when it goes on sale! — impacts the way players approach the games. No one worries too much about rushing through a game they’ve bought for pocket change, but might be much more inclined to play a game they’ve spent $50 on “honestly.” All of which is as it may be. I will only say that, as someone who does still hate turning to a walkthrough, the more typical modern way of playing sometimes dismays me because of the way it can — especially when combined with the ever-distorting fog of nostalgia — lead us to excuse or entirely overlook serious issues of design in vintage games.

But lest I be too harsh on these two middle — middling? — entries in this remarkable series of games, I should remember that they were produced in times of enormous technological change, in a business environment that was changing just as rapidly, and that those realities were often in conflict with their designers’ own best intentions. Corey Cole:

Lori has commented that we started at Sierra almost completely clueless, and had to figure out how to design a Sierra-style game “from scratch.” Then, armed with that knowledge, we confidently started work on the next game, only to have Sierra pull the rug out from under us. Each time the technology and management style changed, we had to rework many of the techniques we had developed to make our previous games.

They may be, in the opinion of this humble reviewer anyway, weaker than their predecessors, but neither Quest for Glory III nor IV is without its interest. If you’d like to see the progression of one of the most unique long-term projects in the history of gaming, by all means, have a look and decide for yourself.

(Sources: Questbusters of May 1992, September 1992, December 1992, September 1993, February 1994; Sierra’s InterAction magazine from Fall 1992, Summer 1993, and Holiday 1993; Computer Gaming World of January 1993 and April 1994; the readme file included with Sierra’s 1998 Quest for Glory Collection; documents and other materials included in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Most of all, my thanks go to Corey Cole for once again allowing me to pepper him with questions, even though he knew beforehand that my opinion of these two games wasn’t as overwhelmingly positive as it had been the last time around.

The entire Quest for Glory series is available for purchase as a package on GOG.com. And by all means check out the Coles’ welcome return to game design in the spirit of Quest for Glory, the recently released Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption. I don’t often get to play games that aren’t “on the syllabus,” as a friend of mine puts it, but I made time for this one, and I’m so glad I did. In my eyes, it’s the best thing the Coles have ever done.)