On August 24, 1990, CompuServe hosted an online discussion on adventure-game design which included Ron Gilbert, Noah Falstein, Bob Bates, Steve Meretzky, Mike Berlyn, Dave Lebling, Roberta Williams, Al Lowe, Corey and Lori Ann Cole, and Guruka Singh Khalsa. This is, needless to say, an incredible gathering of adventuring star power. In fact, I’m not sure that I’ve ever heard of its like in any other (virtual) place. Bob Bates, who has become a great friend of this blog in many ways, found the conference transcript buried away on some remote corner of his hard drive, and was kind enough to share it with me so that I could share it with you today.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you probably recognize all of the names I’ve just listed, with the likely exception only of Khalsa. But, just to anchor this thing in time a bit better, let me take a moment to describe where each of them was and what he or she was working on that August.

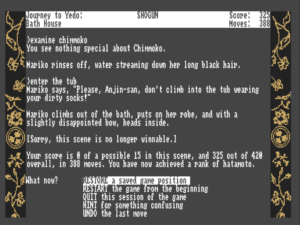

Ron Gilbert and Noah Falstein were at Lucasfilm Games (which was soon to be renamed LucasArts). Gilbert had already created the classic Maniac Mansion a few years before, and was about to see published his most beloved creation of all, one that would have as great an impact among his fellow designers as it would among gamers in general: The Secret of Monkey Island. Falstein had created Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade for Lucasfilm in 1989. Their publisher had also recently released Brian Moriarty’s Loom, whose radically simplified interface, short length, and relatively easy puzzles were prompting much contemporaneous debate.

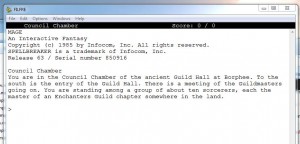

Bob Bates, Steve Meretzky, Mike Berlyn, and Dave Lebling had all written multiple games for the now-defunct Infocom during the previous decade. Bates had recently co-founded Legend Entertainment, where he was working on his own game Timequest and preparing to publish Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls, Meretzky’s first post-Infocom game and Legend’s first game ever, in a matter of weeks. Berlyn had been kicking around the industry since leaving Infocom in 1985, creating perhaps most notably Tass Times in Tonetown for Interplay; he was just finishing up a science-fiction epic called Altered Destiny for Accolade, and would shortly thereafter embark on the Les Manley games, a pair of Leisure Suit Larry clones, for the same publisher. Lebling was at something of a loose end after the shuttering of Infocom the previous year, unsure whether he even wanted to remain in the games industry; he would eventually decide that the answer to that question was no, and would never design another game.

Roberta Williams, Al Lowe, Corey and Lori Ann Cole, and Guruka Singh Khalsa were all working at Sierra. Williams was in the latter stages of making her latest King’s Quest, the first to use 256-color VGA graphics and a point-and-click interface, and the first to be earmarked for CD-ROM as a “talkie.” Al Lowe was, as usual, hard at work on the latest Leisure Suit Larry game, which also utilized Sierra’s newer, prettier, parser-less engine. The Coles were just finishing up Quest for Glory II: Trial by Fire, which would become the last Sierra game in 16-color EGA and the last with a parser.

Khalsa is the only non-designer here, and, as already noted, the only name here with which longtime readers are unlikely to be familiar. He was another of those unsung heroes to be found behind the scenes at so many developers. At Sierra, he played a role that can perhaps best be compared to that played by the similarly indispensable Jon Palace at Infocom. As the “producer” of Sierra’s adventure games, he made sure the designers had the support they needed, acted as a buffer between them and the more business-oriented people, and gently pushed his charges to make their games just a little bit better in various ways. In keeping with his unsung status, he answers only one question here.

We find all of our participants grappling with the many tensions that marked their field in 1990: the urgent need to attract new players in the face of escalating development budgets; the looming presence of CD-ROM and other disruptive new technologies just over the horizon; the fate of text in this emerging multimedia age; the frustration of not always being able to do truly innovative or meaningful work, thanks to a buying public that largely just seemed to want more of the same old fantasy and comedy. It’s intriguing to see how the individual designers respond to these issues here, just as it is to see how those responses took concrete form in the games themselves. By no means is the group of one mind; there’s a spirited back-and-forth on many questions.

I’ve cleaned up the transcript that follows for readability’s sake, editing out heaps of extraneous comments, correcting spelling and grammar, and rejiggering the flow a bit to make everything more coherent. I’ve also added a few footnotes to clarify things or to insert quick comments of my own. Mostly, though, I’ve managed to resist the urge to pontificate on any of what’s said here. You all already know my opinions on many of the topics that are raised. Today, I’m going to let the designers speak for themselves. I hope you’ll find their discussion as interesting and enjoyable as I do.

Let’s plunge right into the questions. Before I start, I’d like to thank Eeyore, Flying Gerbil, Steve Horton, Tsunami, Hercules, Mr. Adventure, and Randy Snow for submitting questions… and I apologize for mangling their questions with my editing. And now — drum roll! — on to the first question!

Imagine ourselves five years down the road, with all the technological developments that implies: CD-ROMs, faster machines, etc. Describe what, for you, the “ideal” adventure will look like. How will it be different from current adventures?

Roberta Williams: I think that “five years down the road” is actually just a year or two away. Meaning that a year or two from now, adventure games are going to have a very slick, sophisticated, professional look, feel, and sound to them, and that that’s the way they’re going to stay for a while — standardization, if you will. I mean, how can you improve on realistic images that look like paintings or photographs? How can you improve on CD-quality voices and music? How can you improve on real movement caught with a movie camera, or drawn by a professional animator? That’s the kind of adventure game that the public is going to start seeing within a year or two. Once adventure games reach a certain level of sophistication in look and feel, standardization will set in, which will actually be a boon for all concerned, both buyers and developers alike. After that, the improvements will primarily be in the performance on a particular machine, but the look will stay essentially the same for a while.

Dave Lebling: But if those wonderful pictures and hi-fi sound are driven by a clunky parser or a mythical “parser-less interface,” is this a big improvement? I think not. We can spend $2 million or $5 million developing a prettier version of Colossal Cave. Let’s improve the story and the interface! That doesn’t have to mean text adventures, but there’s more to adventure games than pictures.

Steve Meretzky: I think that in the future the scope of games won’t be limited by hardware but by the marketplace. Unless the market for adventure games expands, it won’t be economical to create super-large environments, even though the hardware is there to support them.

Mike Berlyn: Well, I think that technology can create products which drive the market and create end users — people who need or want to experience something they could experience only on a computer. In the future, I would like to explore “plot” as a structure, something which is currently impossible due to the state of the current technology. Plot cannot be a variable until storage increases and engines get smarter. I can easily see a plot that becomes a network of possibilities.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: We hope as well that the improvements will be in story and design as well as flash: richer stories, more realistic character interaction, etc. Technology, beyond a certain point which we’ve already reached, really isn’t a big deal. Creativity, and an understanding of the differences between “interactive movies” and games is! The move to professional writers and game designers in the industry is helping.

Ron Gilbert: I think that plot has nothing to do with technology. They are almost unrelated. It’s not CD-ROM or VGA that is going to make the difference, it’s learning how to tell a story. Anyone who is any good can tell a great story in 160 X 200-resolution, 4-color graphics on two disks.

Roberta Williams: It’s not that I don’t think a good plot is important! Obviously it is.

Dave Lebling: I didn’t mean to accuse you of not caring about plot. You of all people know about that! I just think the emphasis on flash is a symptom of the fact that we know how to do flash. Just give us a bigger machine or CD-ROM, and, wham, flash! What we don’t know how to do is plot. I don’t think today’s plots feel more “real” than those of five or eight years ago. Will they be better in five years? I hope so, but I’m not sure. We can’t just blindly duplicate other media without concentrating on the interactivity and control that make ours special. If we work on improving control and the illusion that what we interact with is as rich as reality, then we can do something that none of those other media can touch.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: We have never really used the computer as a medium in its own right.

Steve Meretzky: You haven’t used it to contact the spirit world? [1]One of my favorite things about this transcript is the way that Steve Meretzky and Al Lowe keep making these stupid jokes, and everybody just keeps ignoring them. I fancy I can almost hear the sighs…

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: There are things that can be done on a computer that can’t be done with other mediums. Unfortunately, the trend seems to be away from the computer and towards scanned images and traditional film and animation techniques. [2]It’s worth noting that the trend the Coles describe as “unfortunate” was exactly the direction in which Sierra, their employer, was moving in very aggressive fashion. The Coles thus found themselves blowing against the political winds in designing their games their way. Perhaps not coincidentally, they were also designing the best games coming out of Sierra during this period. If this trend continues, it may be a long time before we truly discover what can be done uniquely with the computer medium. One small example: the much-chastised saved game is a wonderful time- and mind-travel technique that can be a rich tool instead of an unfortunate necessity.

Bob Bates: I agree. You can’t ask a painter at the Art Institute of Chicago to paint you a different scene. You can’t ask a singer at the Met to sing you a different song. (Well, I guess you could, but they frown on requests.) The essence of a computer game is that the player controls the action. The point is to make beautiful music and art that helps the player’s sense of involvement in the game.

I have noticed that a lot of games coming out now are in 256 colors. Does this mean that 256-color VGA is going to be the standard? Has anyone thought about 256 colors in 640 X 480 yet? And how does anyone know who has what?

Bob Bates: The market research on who has what is abominable. As for us, we are releasing our titles with hi-res EGA, which gives us really good graphics on a relatively popular standard, as well as very nice text letters instead of the big clunky ones.

Steve Meretzky: I often get big clunky letters from my Aunt Matilda.

Guruka Singh Khalsa: We’ve been doing a bit of research on who has what hardware, and an amazing number of Sierra customers have VGA cards. Looks like around 60 percent right now. As for 640 X 480 in 256 colors: there’s no hardware standard for that resolution since it’s not an official VGA mode. You won’t see games in that resolution until the engines are more powerful — got to shove them pixels around! — and until it’s an official mode. All SVGA cards use somewhat different calls.

Dave Lebling: The emerging commercial standard is a 386 with VGA and 2 to 4 megs of memory, with a 40-meg hard drive. The home standard tends to lag the commercial one by a few years. But expect this soon, with Windows as the interface.

Does anyone have any plans to develop strictly for or take advantage of the Windows environment?

Dave Lebling: Windows is on the leading edge of the commercial-adoption wave. The newest Windows is the first one that’s really usable to write serious software. There are about 1 million copies of Windows out there. No one is going to put big bucks into it yet. But in a few years, yes, because porting will be easier, and there is a GUI already built, virtual memory, etc., etc. But not now.

With the coming parser-less interfaces and digitized sound, it seems as if text may eventually disappear completely from adventures. Once, of course, adventures were all text. What was gained and what was lost by this shift? Are adventures still a more “literate” form of computer game?

Bob Bates: Well, of course text has become a dirty word of sorts in the business. But I think the problem has always been the barrier the keyboard presents as an input device for those who can’t type. Plus the problems an inadequate or uncaring game designer can create for the player when he doesn’t consider alternate inputs as solutions to puzzles. I think there will always be words coming across the screen from the game. We hope we have solved this with our new interface, but it’s hard for people to judge that since our first game won’t be out for another month…

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: Text will not disappear. Nor should it. We will see text games, parser-less games, and non-text games. And who cares about being “literate”; fun is what matters! I like words. Lori likes words. But words are no longer enough if one also likes to eat — and we do. We also like graphics and music and those other fun things too, so it’s not too big a loss.

Roberta Williams: It’s true that in books stories can be more developed, involving, and interesting than in movies. I believe that there is still room for interactive books. Hopefully there is a company out there who will forget about all the “video” stuff and just concentrate on good interactive stories in text, and, as such, will have more developed stories than the graphic adventure games. But as we progress adventure games in general are going to become more like interactive movies. The movie industry is a larger and more lucrative business than the book industry. For the most part, the adventure-game business will go along with that trend. Currently adventure games are the most literate of computer games, but that may change as more and more text will be lost in the coming years, to be replaced by speech, sound effects, and animation. But I do predict that some company out there will see a huge opportunity in bringing back well-written, high-quality interactive books. It will be for a smaller audience, but still well worth the effort.

Dave Lebling: I think you’re too optimistic about “some company” putting out text products. We are moving from interactive books to interactive movies. I’m not optimistic about the commercial survival of text except in very small doses. [3]This was not what many participating in the conference probably wanted to hear, but it wins the prize of being the most prescient single statement of the evening. Note that Lebling not only predicted the complete commercial demise of text adventures, but he also predicted that they would survive as a hobbyist endeavor; the emphasis on the word “commercial” is original. Unlike in science fiction, you don’t have to follow a trend until it goes asymptotic. Text won’t go away, but its role will be reduced in commercial adventures. Graphics and sound are here to stay.

Al Lowe: With the coming of talkies, it seems as if all those wonderful dialog cards disappeared! You know, the ones that make silent movies so literate? It’s a visual medium! No one asks for silent movies; most Americans won’t even watch a black-and-white movie. Yes, text-only games are more “literate.” So?

Mike Berlyn: As far as the future of text is concerned, my money is on it sticking around. But I’m not sure it’s at all necessary in these kinds of games. The adventure I’m just finishing up has a little bit of text that reiterates what is obvious on the screen, and manages to add to the player’s inputs in other ways to a create fuller experience. But I still don’t think it’s necessary. I’ve done two completely text-less designs, though neither made it to the market.

Bob Bates: I don’t think it’s the loss of text as output that creates a problem for the designer; I think it’s text as input. It’s hard to design tough puzzles that can be solved just by pointing and clicking at things. And if there are no puzzles — tough puzzles — you’re just watching a movie on a very small screen. The days of the text-only adventure are over. Graphics are here to stay, and that’s not a bad thing, as long as they supplement the story instead of trying to replace it.

We’ve seen fantasy adventures, science-fiction adventures, mystery adventures, humorous adventures. Are there any new settings or themes for adventures? Is there any subject or theme that you’ve always wanted to put in an adventure but never had the chance?

Al Lowe: I’ve had ideas for a Wall Street setting for a game, but somehow I can’t get out of this Larry rut. I’d also like to do a very serious game — something without one cheap laugh, just to see if I could. Probably couldn’t, though. A serious romance would be good too.

Roberta Williams: There should be as many settings or themes for adventure games as there are for fictionalized books and movies. After all, an adventure game is really just an interactive story with puzzles and exploration woven into it. There are many themes that I personally would like to do, and hopefully will someday: an historical or series of historical adventure games; a horror game; an archaeological game of some sort; possibly a western. In between King’s Quests, of course.

Noah Falstein: I’ve always wanted to do a time-travel game with the following features: no manual save or load, it’s built automatically into the story line as a function of your time-travel device; the opportunity to play through a sequence with yourself in a later — and then earlier — time; and the ability to go back and change your changes, ad infinitum. Of course, the reason I’m mentioning all this is that I — and others here — have fried our brains trying to figure out how this could be accomplished. We’d rather see someone else do it right. Or die trying.

Ad infinitum? Won’t that take a lot of memory?

Noah Falstein: Recursion!

Dave Lebling: Gosh, my fantasy is your fantasy! I’ve always wanted to do a game based on Fritz Leiber’s Change War stories — you know, “tomorrow we go back and nuke ancient Rome!” Funny thing is, I’ve always run up against the same problem you ran up against.

Mike Berlyn: My fantasy is to finish a game that my wife Muffy and I were working on for the — sniff! — dead Infocom. It was a reality-based game that had a main character going through multiple/parallel lives, meeting people he’d met before but who were different this time through. In that way, the relationships would be different, the plot would be different, and their lives would interact differently.

Steve Meretzky: In my fantasy, I answer the door and Goldie Hawn is standing there wearing… oh, we’re talking adventure games now, aren’t we? A lot of the genres I was going to mention have already been mentioned. But one is historical interactive nonfiction. I know that Stu Galley has always wanted to do a game in which you play Paul Revere in April of 1775. And before I die I’m going to do a Titanic game. [4]Steve Meretzky’s perennial Titanic proposal, which he pitched to every publisher he ever worked with, became something of an industry in-joke. There’s just no market for such a game, insisted each of the various publishers. When James Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic became the first ever to top $1 billion at the box office, and a modest little should-have-been-an-obscurity from another design team called Titanic: Adventure Out of Time rode those coattails to sales of 1 million copies, the accusations flew thick and fast from Meretzky’s quarter. But to no avail; he still hasn’t gotten to make his Titanic game. On the other hand, he’s nowhere near death, so there’s still time to fulfill his promise… Also, in my ongoing effort to offend every man, woman, and child in the universe, someday I’d like to write an Interactive Bible, which would be an irreverent comedy, of course. Also, I’d like to see a collection of “short story” adventure games for all those ideas which aren’t big enough to be a whole game. [5]Meretzky had pitched both of these ideas as well to Infocom without success. In the longer term, however, he would get one of his wishes, at least after a fashion. “Short stories” have become the norm in modern interactive fiction, thanks largely to the Interactive Fiction Competition and its guideline that it should be possible to play an entrant to completion within two hours.

Bible Quest: So You Want to Be a God?. I like it, I like it.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: Ah, but someone will sue over the trademark… [6]Legal threats from the makers of the board game HeroQuest had recently forced the Coles to change the name of their burgeoning series of adventure/CRPG hybrids from the perfect Hero’s Quest to the rather less perfect Quest for Glory. Obviously the fresh wound still smarted.

Bob Bates: The problem of course is marketing. The kinds of games we want to write aren’t always the kinds of games that will sell. This presents something of a quandary for those of us who like to eat.

This question was submitted by Tsunami, and I’ll let him ask in his own words: “Virtually every game I have played on my computer is at least partially tongue-in-cheek. What I am interested in is games with mature themes, or at least a more mature approach to their subjects. Games that, like good movies or plays, really scare a player, really make them feel a tragedy, or even make them angry. What are each of you doing to try to push games to this next level of human interaction?”

Steve Meretzky: Well, I think I already did that with A Mind Forever Voyaging, and it did worse commercially speaking than any other game I’ve ever done. As Bob just said, we have to eat. I’d much rather write a Mind Forever Voyaging than a Leather Goddesses of Phobos, but unless I become independently wealthy, or unless some rich benefactor wants to underwrite such projects, or unless the marketplace changes a lot, I don’t think I’ll be doing a game like A Mind Forever Voyaging in the near future. Sigh.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: Computers are so stupid that even the smartest game tends to do silly things. So, it’s easier to write a silly game. And the development process on a humorous game tends to be more fun. Quest for Glory II: Trial By Fire is fundamentally a very serious game in terms of story line, but we kept lots of silly stuff in to break up the tension. I call it the “roller-coaster effect.” We want the player to get extremely intense about the game at points, but then have a chance to catch his or her breath with comic relief and plain fun.

Bob Bates: My games are usually fairly “mature,” but when 90 percent of what a player tries to do in a game is wrong, you have to keep him interested when he is not solving a puzzle. The easiest way to do this is with humor; you don’t want him mad at you, after all. But I agree that we all should strive to create emotions in the player like what we all felt when Floyd died in Planetfall.

Roberta Williams: I agree with the sentiment that most adventure games, at least up to now, have been not quite “serious” in their approach to the subject matter at hand. I think the reason for that, for the most part, is that professional writers or storytellers have not had their hands in the design of a game. It’s been mostly programmers who have been behind them. I’m not a professional writer either, but I’m trying to improve myself in that area. With The Colonel’s Bequest, I did attempt a new theme, a murder mystery, and tried to make it more mature in its subject matter — more “plot” oriented. I attempted to put in classic “scare” tactics and suspense. I tried to put in different levels of emotion, from repulsion to sadness to hilarity. Whether I accomplished those goals is up to the player experiencing the game. At least I tried!

Noah Falstein: I venture to predict that we all intend to push games this way, or want to but can’t afford it — or can’t convince a publisher to afford it. But I’ll toot the Lucasfilm horn a bit; imagine the Star Wars fanfare here. One way we’re trying to incorporate real stories into games is to use real storytellers. Next year, we have a game coming out by Hal Barwood, who’s been a successful screenwriter, director, and producer for years. His most well-known movies probably are the un-credited work he did on Close Encounters and Dragonslayer, which he co-wrote and produced. He’s also programmed his own Apple II games in 6502 assembly in his spare time. I’ve already learned a great deal about pacing, tension, character, and other “basic” techniques that come naturally — or seem to — to him. I highly recommend such collaborations to you all. I think we’ve got a game with a new level of story on the way. [7]After some delays, the game Falstein is talking about here would be released in 1992 as Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. It would prove to be a very good adventure game, if not quite the medium-changer Falstein describes.

Mike Berlyn: I disagree with the idea that hiring professional storytellers from other media will solve our problems for us. Creating emotions is the goal here, if I understood the question. It isn’t whether we write humor or horror, it’s how well we do it. This poses a serious problem. Interactivity is the opposite of the thing that most… well, all storytellers, regardless of medium, require to create emotion. Emotion is created by manipulation. And it is impossible to manipulate emotions when you don’t know where the player has been and you don’t know where the player is going. In linear fiction, where you know what the “player” has just experienced; you can deliberately and continuously set them up. This is the essence of drama, humor, horror, etc. Doing this in games requires a whole different approach. Utilizing an experienced linear writer only tends to make games less game-ish, less interactive, and more linear. In a linear game like Loom, you’re not providing an interactive story or an adventure game. All you’re doing is making the player work to see a movie.

Dave Lebling: Well, emotion also comes from identification with the character in the story. You can’t easily identify in a serious way with a character who looks like a 16 X 16-pixel sprite. [8]It’s interesting to see Lebling still using the rhetoric from Infocom’s iconic early advertising campaigns. If he or she is silly-looking, he or she isn’t much more silly-looking than if he’s serious-looking: for example, Larry Laffer versus Indy in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. So, you are at a disadvantage being serious in graphical games. Better graphics will improve that eventually. But even so, I think Bob hit the point perfectly: the player does a lot of silly things, even if there is no parser — running into rocks in the graphic games, for example — and you can’t stay serious. The other thing is that, in my experience, serious games don’t sell. Infocom’s more serious games sold poorly. Few others have tried, and most of those have sold poorly too.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: A really good game — or story — elicits emotions rather than creating them. A good design opens up the player’s imagination instead of forcing them along a path. A frustrated player is too busy being angry at the computer to experience the wonder and mystery of his or her character and the game’s world. By having fair puzzles and “open” stories, we allow players to emote and imagine.

Okay, now we turn from software to hardware. One of the most striking developments over the last few years has been the growing use of MS-DOS machines for game development. This has led some Amiga and Mac owners to complain that there aren’t any good adventures out for their machines, or that the games that are out for those platforms don’t make good use of their full graphics and sound capabilities. How can this problem be solved?

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: Well, I just about went broke trying to develop Atari ST software a few years ago. This was what made it possible to pull up roots and come to Sierra to do games. But I think the real value of all the alternative platforms has been to force IBM and the clone-makers to play catch-up. Myself, I’m waiting for ubiquitous CD-ROM and telecom. I’d really like to be doing multiplayer games in a few years. In the meantime, the cold hard reality is that IBM clones is where the money is — and money is a good thing.

Roberta Williams: Ha! We at Sierra, probably the most guilty of developing our games on MS-DOS machines, are trying to rectify that problem. This past year, we have put teams of programmers on the more important non-MS-DOS platforms to implement our new game-development system in the best way possible for those machines. Emphasis is on the unique capabilities of each machine, and to truly be of high quality on each of them. Our new Amiga games have been shipping for several months now, and have been favorably received — and our Mac games are nearly ready.

Dave Lebling: Get an installed base of 10 million Macs or Amigas and you’ll see plenty of games for them. Probably even fewer are needed, since programmers have the hots for those platforms. But in reality what you need is companies like Sierra that can leverage their development system to move to different platforms. As Windows and 386-based machines become the IBM standard, the differences among the platforms become less significant, and using an object-oriented development system lets you port relatively easily, just like in the old days. Graphics will still be a problem, as the transforms from one machine to another will still be a pain.

Al Lowe: Money talks. When Mac games outsell MS-DOS games, you’ll see Mac-designed games ported to PCs. When Amiga games are hot, etc. In other words, as long as MS-DOS sales are 80 percent or more of the market, who can afford to do otherwise?

Mike Berlyn: I think we all want our games on as many systems as possible, but in reality the publishers are the ones who make the decisions.

When you design a game, do you decide how hard it’s going to be first, or does the difficulty level just evolve?

Ron Gilbert: I know that I have a general idea of how hard I want the game to be. Almost every game I have done has ended up being a little longer and harder than I would have liked.

Noah Falstein: I agree. I’ve often put in puzzles that I thought were easy, only to find in play-testing that the public disagreed. But since Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade I firmly believe that one good way to go is to put in multiple solutions to any puzzles that are showstoppers, and to make the remaining ones pretty easy. I think that’s the best for the players.

Dave Lebling: I think alternate solution are a red herring because you can’t make them radically different in difficulty or the easier one will always be found first.

Noah Falstein: But if you provide incentives to replay the game, you can make both beginners happy, who will find the easy alternative, and experienced gamers happy, who will want to find every solution…

Dave Lebling: Yes, but what percentage of people replay any game? What percentage even finish?

Steve Meretzky: Games that are intended for beginners — e.g., Wishbringer — are designed to be really easy, and games intended for veterans — e.g., Spellbreaker — are designed to be ball-busters. But since of course you end up getting both types for any game, my own theory is to start out with easy puzzles, have some medium-tough puzzles in the mid-game, and then wrap it up with the real whoppers. (Don’t ask me what the Babel-fish puzzle was doing right near the beginning of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.)

Roberta Williams: Usually the decision of how difficult the game is going to be is made about the time that the design actually begins. And that decision is based on who the main player of the game is going to be. In other words, if it’s an adventure game for children, then obviously the game will be easier. If it’s for families, the game will be harder than for children, but easier than a game strictly for adults. If it’s a game with adults in mind, then the difficulty level lies with the designer as he or she weaves the various puzzles into the plot of the story. I think even then, though, the decision of how difficult it’s going to be is made around the start of the design. Speaking personally, I usually have a good sense of which puzzles are going to be more difficult and which ones are easier to solve. There have been a few times when I miscalculated a puzzle. For instance, in King’s Quest II I thought the bridle-and-snake puzzle was fairly straightforward, but no, it wasn’t. And in The Colonel’s Bequest I didn’t think that discovering the secret passage in the house would be as difficult for some people as it turned out to be.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: We try to keep the puzzles on the easy side in the sense of being fair; hints are somewhere in the game. But sometimes the best-laid plans of designers and developers go out the window when programming push-time comes, to mix several metaphors. But we definitely plan difficulty level in advance. The Quest for Glory series was intended to be somewhat on the easy side as adventure games go because we were introducing the concept of role-playing at the same time.

Dave Lebling: I think it’s relatively easy to make a game really hard or really easy. What’s tough is the middle-ground game. They tend to slop over to one extreme or the other, sometimes both in different puzzles, and you get a mishmash.

Mike Berlyn: I tend to design games that have various levels of difficulty within themselves, and so can appeal to a broad range of players. Like Steve, I like to open with an easy one and then mix up the middle game, saving the toughest stuff for the endgame.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: We made a real effort to graduate the puzzles in Quest for Glory I, easier ones in the early phases.

Al Lowe: Does anyone else feel we should lighten up on our difficulty level so as to attract a broader audience and broaden our base of players?

Mike Berlyn: Making games easier isn’t going to attract more players. What will is designing and implementing them better.

Roberta Williams: Perhaps a parser-less interface would help. But I still think that each game should be thought out in advance as to who the target audience is, and then go from there on difficulty level.

Bob Bates: I agree that what is needed is not easier puzzles. I think that players want tough but fair puzzles. Where’s the rush that comes from solving an easy puzzle? What will keep them coming back for more?

Dave Lebling: One person’s easy puzzle is another’s never-solved brain-buster. There need to be a range of games and a range of puzzles in each game. Even Wishbringer, Infocom’s “easiest” game, had huge numbers of people stuck on the “easiest” puzzles.

Adventure designs have recently been criticized for becoming shorter and/or easier. Do you agree with this criticism, and, if so, how do you change a design to make a product longer and/or harder? And are harder games commercially viable?

Dave Lebling: Games are already too easy and not easy enough, and other paradoxes. Meaning that the intentional puzzles are getting too easy, and the unintentional ones — caused by size limitations, laziness, lousy parsers, bugs, etc. — are still too hard. Harder games are commercially viable, but only if the unintentional difficulty is reduced. We aren’t real good at that yet.

Roberta Williams: It may be true, to a certain extent, that adventure games have become shorter and/or easier than in the past. Four to ten years ago, adventure games were primarily text-oriented, and, as such, could be more extensive in scope, size, and complexity. Since the introduction of graphics, animation, and sound — and, coming up, speech — it is much more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve the same sort of scope that the earlier adventure games were able to accomplish. The reason for this is mainly limitations of memory, disk space, time, and cost. We adventure-game developers increasingly have to worry about cramming in beautiful graphics, realistic animation, wonderful sound, and absorbing plots, along with as many places to explore as possible, alternate paths or choices, and interesting puzzles. There is just so much space to put all that in. Something has to give. Even CD technology will not totally solve that problem. Though there is a very large disk capacity with CD, there is still a relatively small memory capacity. Also, the way the adventure-game program needs to be arranged on the CD creates problems. And as usual, with the new CD capabilities, we adventure-game developers are sure to create the most beautiful graphics you’ve ever seen, the most beautiful music you’ve ever heard, etc., etc. And that uses up disk space, even on CD.

Mike Berlyn: Shorter? Yeah, I suppose some of the newer games, whose names will remain untyped, are easier, shorter, etc. But unfortunately, they aren’t cheaper to make. I hate to tell you how much Altered Destiny is going to cost before it’s done. Accolade and myself have over ten man-years in this puppy, and a cast of many is creating it. When I created Oo-Topos or Cyborg or even Suspended, the time and money for development were a fraction of what this baby will cost. In addition, games like King’s Quest IV are larger, give more bang for the buck, and outshine many of the older games.

Steve Meretzky: A few years ago, I totally agreed with the statement that adventure games were getting too short and easy. Then I did Zork Zero, which was massive and ultimately quite hard. A good percentage of the feedback distilled down to “Too big!” It just took too long to play, and it was too hard to keep straight everything you had to do to win the game. Plus, of course, it was a major, major effort to design and implement and debug such a huge game. So, I’ve now come to the conclusion that a nice, average, 50-to-100-room, 20-to-30-hours-of-play-time, medium-level-of-difficulty game is just about right.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: There is plenty of room left for easier games, especially since most “hard” games are hard only because they are full of unfair outguess-the-designer — or programmer or parser — puzzles. Nobody wants to play a game and feel lost and frustrated. Most of us get enough of that in our daily lives! We want smaller, richer games rather than large, empty ones, and we want to see puzzles that further the story rather than ones that are just thrown in to make the game “hard.”

Al Lowe: I’ve been trying for years to make ’em longer and harder!

Groan…

Al Lowe: But seriously, I have mixed emotions. I work hard on these things, and I hate to think that most people will never see the last half of them because they give up in defeat. On the other hand, gamers want meaty puzzles, and you don’t want to disappoint your proven audience. I think many games will become easier and easier, if only to attract more people to the medium. Of course, hard games will always be needed too, to satisfy the hardcore addicts. Geez, what a cop-out answer!

Bob Bates: You have to give the player his money’s worth, and if you can just waltz through a game, then all you have is an exercise in typing or clicking. The problem is that the definition of who the player is is changing. In trying to reach a mass market, some companies are getting away from our puzzle roots. The quandary here is that this works. The big bucks are in the mass market, and those people don’t want tough puzzles. The designers who stay behind and cater to the puzzle market may well be painting themselves into a niche.

Noah Falstein: Al and Bob have eloquently given the lead-in I was intending. But I’d like to go farther and say that we’re all painting ourselves into a corner if we keep catering to the 500,000 or so people that are regular players — and, more importantly, buyers — of adventure games. It’s like the saber-toothed tiger growing over-specialized. There are over 15 million IBM PC owners out there, and most of them have already given up on us because the games are too… geeky. Sorry, folks! Without mentioning that game that’s looming over this discussion, we’ve found that by making a very easy game, we’ve gotten more vehement, angry letters than ever before — as well as more raves from people who never played or enjoyed such games before. It seems to be financially worthwhile even now, and if more of us cater to this novice crowd, with better stories instead of harder puzzles, there will be a snowball effect. I think this is worth working towards, and I hope some of you will put part of your efforts into this. There’s always still some room for the “standard-audience” games. Interestingly enough, 60 to 100 rooms and 20 to 30 hours is precisely the niche we arrived at too! But let’s put out at least one more accessible game each year.

Dave Lebling: Most of the points I wanted to make have been made, and made well, but I’d like to add one more. What about those 20 million or more Nintendo owners out there? What kinds of games will hook them, if any? Have they written us off? I don’t think our fraction of the IBM market is quite as small as Noah’s figures make it look. Many of those IBM machines are not usable for games by policy, as they are in corporate settings. But all of the Nintendos are in home settings. Sure, they don’t have keyboards, but if there was a demand for our sort of game — a “puzzle” game, for want of a better word — there would be a keyboard-like interface or attachment, like the silly gun or the power glove. There isn’t. Why? Are we too geeky? Are puzzles and even the modicum of text that is left too much? We will have the opportunity to find out when the new game systems with keyboards start appearing in the US.

What do you all think about the idea of labeling difficulty levels and/or estimated playing time on the box, like Infocom used to do at one time?

Steve Meretzky: That was a pretty big failure. As was said earlier about puzzles, one person’s easy is another person’s hard.

Al Lowe: Heh, heh…

Steve Meretzky: For example, I found Suspended to be pretty easy, having a mind nearly as warped as Berlyn’s, but many people consider it one of Infocom’s hardest.

Bob Bates: The other Infocommies here can probably be more accurate, but my recollection is that labeling a game “advanced” scared off people, and labeling a game “easy” or “beginner” turned off lots of people too. So most of the games wound up being released as “standard,” until they dropped the scheme altogether. Still, I think some sort of indication on a very easy game, like the ones Noah was talking about, is in order. The customer has a right to know what he is purchasing.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: But Loom was rated as an easy game, and people who were stumped on a puzzle felt like this meant they were dumb or something.

Mike Berlyn: Good point! I’m not sure that labeling a product as being easy, medium, or difficult is a real solution. I know some games which were labeled “beginner” level were too tough for me. What we as designers need to do is write better, fairer, more rounded games that don’t stop players from exploring, that don’t close off avenues. It isn’t easy, but it’s sure my goal, and I like to think that others share this goal.

Okay, this is the last question. What is your favorite adventure game and why?

Noah Falstein: This will sound like an ad, but our audience constitutes a mass market. Ron Gilbert’s next game, The Secret of Monkey Island, is the funniest and most enjoyable adventure game I’ve ever played, including the others our company has done. I’ve laughed out loud reading and rereading the best scenes.

Steve Meretzky: Based simply on the games I’ve had the most fun playing, it’s a tie between Starcross — the first ever adventure game in my genre of choice, science fiction — and the vastly ignored and underrated Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It.

Roberta Williams: I hate to say it, but I don’t play many adventure games, including our own! I really love adventure games, though. It was this love of adventure gaming that brought me into this business. However, nowadays I’m so busy, what with working on games of my own, helping my husband run the company, taking care of the kids and the house, and doing other extracurricular activities, that I literally don’t have time to play adventure games — and we all know how much time it does take to play them! Of the adventure games that I’ve played and/or seen, I like the games that Lucasfilm produces; I have a lot of respect for them. And I also enjoy the Space Quest and Leisure Suit Larry series that my company, Sierra, produces. Of my own games, I always seem to favor the game I’m currently working on since I’m most attached to it at that given moment. Right now, that would be King’s Quest V. But aside from that, I am particularly proud of The Colonel’s Bequest since it was a departure for me, and very interesting and complicated to do. I am also proud of Mixed-Up Mother Goose, especially the new version coming out. And looking way back, I still have fond memories of Time Zone, for any of you who may remember that one.

Corey and Lori Ann Cole: Of adventure games, we liked the original mainframe Zork and Space Quest III. But our favorite games are Dungeon Master and Rogue, the only games we keep going back to replay. As for our favorite of all two games we’ve done, we’re particularly proud of what we are doing with Quest for Glory II: Trial By Fire. We’re also proud of the first game, but we think Trial by Fire is going to be really great. Okay, end of commercial, at least as soon as I say, “Buy our game!” But seriously, we’re pleased with what we’ve done with the design.

Bob Bates: “You are standing outside a white house. There is a mailbox here.”

Mike Berlyn: This is my least favorite question in the world. (Well, okay, I could think up some I’d like less.) But it’s a toss-up between A Mind Forever Voyaging, Starcross, and the soon-to-be-forgotten masterpiece, Scott Adams’s Pirate Adventure. Yoho.

Dave Lebling: Hitchhiker’s Guide and Trinity. Both well thought-out, with great themes. But beyond those, the original Adventure. I just played it a little bit last night, and I still get a thrill from it. We owe a lot to Will Crowther and Don Woods, and I think that’s an appropriate sentiment to close with.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | One of my favorite things about this transcript is the way that Steve Meretzky and Al Lowe keep making these stupid jokes, and everybody just keeps ignoring them. I fancy I can almost hear the sighs… |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It’s worth noting that the trend the Coles describe as “unfortunate” was exactly the direction in which Sierra, their employer, was moving in very aggressive fashion. The Coles thus found themselves blowing against the political winds in designing their games their way. Perhaps not coincidentally, they were also designing the best games coming out of Sierra during this period. |

| ↑3 | This was not what many participating in the conference probably wanted to hear, but it wins the prize of being the most prescient single statement of the evening. Note that Lebling not only predicted the complete commercial demise of text adventures, but he also predicted that they would survive as a hobbyist endeavor; the emphasis on the word “commercial” is original. |

| ↑4 | Steve Meretzky’s perennial Titanic proposal, which he pitched to every publisher he ever worked with, became something of an industry in-joke. There’s just no market for such a game, insisted each of the various publishers. When James Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic became the first ever to top $1 billion at the box office, and a modest little should-have-been-an-obscurity from another design team called Titanic: Adventure Out of Time rode those coattails to sales of 1 million copies, the accusations flew thick and fast from Meretzky’s quarter. But to no avail; he still hasn’t gotten to make his Titanic game. On the other hand, he’s nowhere near death, so there’s still time to fulfill his promise… |

| ↑5 | Meretzky had pitched both of these ideas as well to Infocom without success. In the longer term, however, he would get one of his wishes, at least after a fashion. “Short stories” have become the norm in modern interactive fiction, thanks largely to the Interactive Fiction Competition and its guideline that it should be possible to play an entrant to completion within two hours. |

| ↑6 | Legal threats from the makers of the board game HeroQuest had recently forced the Coles to change the name of their burgeoning series of adventure/CRPG hybrids from the perfect Hero’s Quest to the rather less perfect Quest for Glory. Obviously the fresh wound still smarted. |

| ↑7 | After some delays, the game Falstein is talking about here would be released in 1992 as Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. It would prove to be a very good adventure game, if not quite the medium-changer Falstein describes. |

| ↑8 | It’s interesting to see Lebling still using the rhetoric from Infocom’s iconic early advertising campaigns. |