As the dust settled and the shock faded in the months that followed the shuttering of Infocom, most of the people who had worked there found they were able to convince themselves that they were happy it was finally over, relieved that a clean sharp break had been made. Sure, they had greeted the initial bombshell that the jig was finally up with plenty of disbelief, anger, and sadness, but the fact remained that the eighteen months before that fateful day, during which they had watched their company lose its old swagger, its very sense of itself, had been if anything even more heartbreaking. And yes, there would be plenty of second-guessing among them in the years to come about what might have been if Cornerstone had never existed or if Bruce Davis hadn’t taken over control of Mediagenic, [1]Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. but Infocom’s story did nevertheless feel like it had run its natural course, leaving behind something that all of the Bruce Davises in the world could never take away: that stellar 35-game catalog, unmatched by any game developer of Infocom’s era or any era since in literacy, thoughtfulness, and relentless creative experimentation. With that along with all of their fine memories of life inside Infocom’s offices to buoy them, the former employees could move on to the proverbial next chapter in life feeling pretty good about themselves, regarding their time at Infocom as, as historian Graham Nelson so memorably put it, “a summer romance” that had simply been too golden to stay any longer.

Yet there was at least one figure associated with Infocom who was more inclined to rage against the dying of the light than to go gentle into that good night. Bob Bates had come to the job of making text adventures, a job he enjoyed more than anything else he had ever done, just a little bit too late to share the sense of closure felt by the rest of Infocom. Which isn’t to say he hadn’t managed to accomplish anything in the field: Bob had formed a company to challenge Infocom — a company named, appropriately enough, Challenge — that wound up joining them as the only outside developer ever allowed to copy Infocom’s in-house tools and make games for them under contract. Still, it had all happened very late in the day. When all was said and done, he had the dubious distinction of having made the last all-text Infocom game ever, followed by their very last game of all. His summer romance, in other words, had started in the last week of the season, and he’d barely gotten past first base. When he returned from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to his home near Washington, D.C., on the stormy evening of May 5, 1989, having just been informed by Infocom’s head Joe Ybarra that Infocom’s Cambridge offices were being closed and Challenge’s services wouldn’t be needed anymore, his brief life in text adventures just felt so incomplete. And then, he found his roof was leaking. Of course it was.

Some of Bob’s restless dissatisfaction must have come across when, after that unhappy weekend was in the past, he called up Mike Verdu to tell him he would no longer be able to employ Mark Poesch and Duane Beck, the two programmers Mike’s company had sent out to work with Challenge. A remarkably young executive even in a field that has always favored the young, Mike was only in his mid-twenties, but already had an impressive CV. In his second year at university, he had dropped out to form a consulting company he named Paragon Systems, which had come to employ Poesch and Beck. The two had been sent to Challenge when Bob came calling on Paragon, looking for help programming the games he had just signed a contract with Infocom to create. During the period when Challenge was making games for Infocom, Mike had sold Paragon to American Systems Corporation, a computer-integration firm that did significant business with the Department of Defense. He had stayed on thereafter with the bigger company as director of one of their departments, and Poesch and Beck had continued to work with Challenge, albeit under the auspices of ASC rather than Paragon. But now that would all be coming to an end; thus Bob’s phone call to Mike to inform him that he would have to terminate Challenge’s arrangement with ASC.

In truth, Bob and Mike didn’t know each other all that well prior to this conversation. Mike had always loved games, and had loved having a game company as a client, but Challenge had always had to remain for him as, as he puts it today, “one of many.” The call that Bob now made to Mike therefore began more as a simple transaction between customer and service provider than as a shared commiseration over the downfall of Bob’s business. Still, something that Bob said must have sparked Mike’s interest. The call continued far longer than it ought to have, and soon multiplied into many more conversations. In fairly short order, the conversations led to a suggestion from Mike: let’s start a new company to make and publish text adventures in the Infocom tradition. He even believed he could convince ASC to put up the bulk of the funding for such a company.

Set aside the fact that text adventures were allegedly dying, and the timing was oddly perfect. In 1989 the dominoes were toppling all over Eastern Europe, the four-decade Cold War coming to an end with a suddenness no one could have dreamed of just a few years before. Among the few people in the West not thoroughly delighted with recent turns of events were those at companies like ASC, who were deeply involved with the Department of Defense and thus had reason to fear the “peace dividend” that must lead to budget cuts for their main client and cancelled contracts for them. ASC was eager to diversify to replace the income the budget cuts would cost them; they were making lots of small investments in lots of different industries. In light of the current situation, an investment in a computer-game company didn’t seem as outlandish as it might have a year or two before, when the Reagan defense buildup was still booming, or, for that matter, might have just a year or two later, when the Gulf War would be demonstrating that the American military would not be idle on the post-Cold War world stage.

Though they had a very motivated potential investor, the plan Bob and Mike were contemplating might seem on the face of it counter-intuitive if not hopeless to those of you who are regular readers of this blog. As I’ve spent much time describing in previous articles, the text adventure had been in commercial decline since 1985. That very spring of 1989 when Bob and Mike were starting to talk, what seemed like it had to be the final axe had fallen on the genre when Level 9 had announced they were getting out of the text-adventure business, Magnetic Scrolls had been dropped by their publisher Rainbird, and of course Infocom had been shuttered by their corporate parent Mediagenic. Yet Bob and Mike proposed to fly in the face of that gale-force wind by starting a brand new company to make text adventures. What the hell were they thinking?

I was curious enough about the answer to that question that I made it a point to ask it to both Bob and Mike when I talked to them recently. Their answers were interesting enough, and said enough about the abiding love each had and, indeed, still has for the genre of adventures in text that I want to give each of them a chance to speak for himself here. First, Mike Verdu:

I believed that there was a very hardcore niche market that would always love this type of experience. We made a bet that that niche was large enough to support a small company dedicated to serving it. The genre was amazing; it was the closest thing to the promise of combining literature and technology. The free-form interaction a player could have with the game was a magical thing. There’s just nothing else like it. So, it didn’t seem like a dying art form to me. It just seemed that there were these bigger companies that the market couldn’t support that were collapsing, and that there was room for a smart niche player that had no illusions about the market but could serve that market directly.

I will say that when Bob and I were looking for publishing partners, and went to some trade conferences — through Bob’s connections we were able to meet people like Ken and Roberta Williams and various other luminaries in the field at the time — everybody said, “You have no idea what you’re doing. The worst idea in the world is to start a game company. It’s the best way to take a big pile of money and turn it into a small pile of money. Stay away!” But Bob and I are both stubborn, and we didn’t listen.

Understanding your market opportunity is really key when you’re forming a company. With Legend, we were very clear-eyed about the fact that we were starting a small company to serve a small market. We didn’t think it would grow to be a thousand people or take over the world or sell a million units of entertainment software per year. We thought there was this amazing, passionate audience that we could serve with these lovingly crafted products, and that would be very fulfilling creatively. If you’re a creative person, I think you have to define how big the audience is that is going to make you feel fulfilled. Bob and I didn’t necessarily have aspirations to reach millions of people. We wanted to reach enough people that we could make our company viable, make a living, and create these products that we loved.

And Bob Bates:

We recognized the risk, but basically we just still believed in the uniqueness of the parser-driven experience — in the pleasure and the joy of the parser-driven experience. By then, there were no other major parser-driven games around, and we felt that point-and-click was a qualitatively different experience. It was fun, but it was different. It was restrictive in terms of what the player could do, and there was a sense of the game world closing in on you, that you could only do what could be shown. Brian Moriarty had a great quote that I don’t remember exactly, but it was something like “you can only implement what you can afford to show, and you can’t afford to show anything.” As a player, I loved the freedom to input whatever I wanted, and I loved the low cost of producing that [form of interaction]. If there’s an interesting input or interaction, and I can address it in a paragraph of text, that’s so much cheaper than having an artist spend a week drawing it. Text is cheap, so we felt we could create games economically. We felt that competition in that niche wasn’t there anymore, and that it was a fun experience that there was still a market for.

Reading between the lines just a bit here, we have a point of view that would paint the failure of Infocom more as the result of a growing mismatch between a company and its market than as an indication that it was genuinely impossible to still make a living selling text adventures. Until 1985, the fulcrum year of the company’s history, Infocom had been as mainstream as computer-game publishers got, often placing three, four, or even five titles in the overall industry top-ten sales lists each month. Their numbers had fallen off badly after that, but by 1987 they had stabilized to create a “20,000 Club”: most games released that year sold a little more or less than 20,000 copies. Taking into account the reality that every title would never appeal enough to every fan to prompt a purchase — especially given the pace at which Infocom was pumping out games that year — that meant there were perhaps 30,000 to 40,000 loyal Infocom fans who had never given up on the company or the genre. Even the shrunken Infocom of the company’s final eighteen months was too big to make a profit serving that market, which was in any case nothing Bruce Davis of Mediagenic, fixated on the mainstream as he was, had any real interest in trying to serve. A much smaller company, however, with far fewer people on the payroll and a willingness to lower its commercial expectations, might just survive and even modestly thrive there. And who knew, if they made their games really well, they might just collect another 30,000 or 40,000 new fans to join the Infocom old guard.

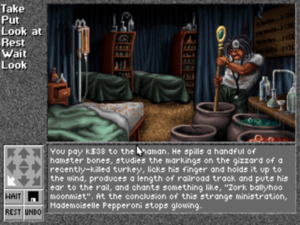

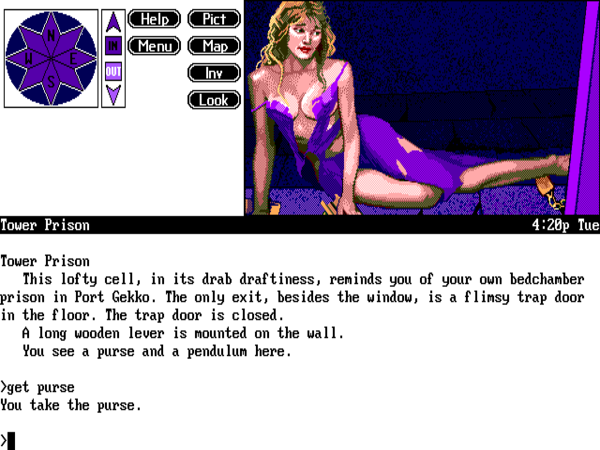

This wasn’t to say that Bob and Mike could afford to return to the pure text that had sufficed for 31 of Infocom’s 35 adventure games. To have any chance of attracting new players, and quite possibly to have any chance of retaining even the old Infocom fans, they were well aware that some concessions to the realities of the contemporary marketplace would have to be made. Their games would include an illustration for every location along with occasional additional graphics, sound effects, and music to break up their walls of text. Their games would, in other words, enhance the Infocom experience to suit the changing times rather than merely clone it.

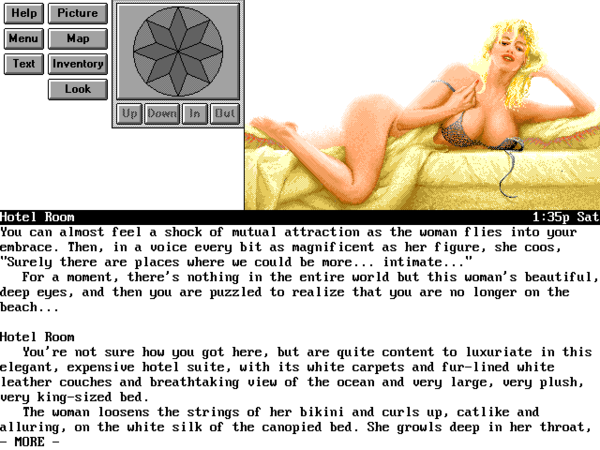

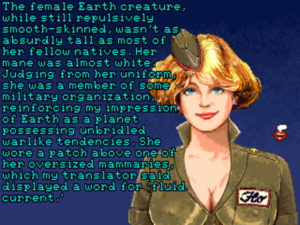

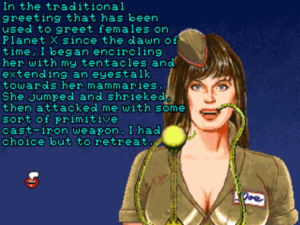

In the same spirit of maximizing their text adventures’ contemporary commercial potential, they very early on secured the services of Steve Meretzky, Infocom’s single most well-known former Implementor, who had worked on some of the company’s most iconic and successful titles. With Meretzky’s first game for their company, Bob and Mike would try to capitalize on his reputation as the “bad boy of adventure gaming” — a reputation he enjoyed despite the fact that he had only written one naughty adventure game in his career to date. Nevertheless, Bob encouraged Meretzky to “take the gloves off,” to go much further than he had even in his previous naughty game Leather Goddesses of Phobos. Meretzky’s vision for his new game can perhaps be best described today as “Animal House meets Harry Potter” (although, it should be noted, this was many years before the latter was published). It would be the story of a loser who goes off to Sorcerer University to learn the art and science of magic, whilst trying his best to score with chicks along the way. Of course, this being an adventure game, he would eventually have to save the world as well, but the real point was the spells and the chicks. The former would let Meretzky revisit one of the most entertaining puzzle paradigms Infocom had ever devised: the Enchanter series’s spell book full of bizarre incantations that prove useful in all sorts of unexpected ways. The latter would give Bob and Mike a chance to prove one more time the timeless thesis that Sex Sells.

So, the Meretzky game seemed about as good as things could get as a commercially safe bet, given the state of text adventures in general circa 1989. Meanwhile, for those players less eager to be titillated, Bob Bates himself would make what he describes today as a “classical” adventure, a more sober-minded time-travel epic full of intricately interconnected puzzles and environments. Between the two, they would hopefully have covered most of what people had liked about the various games of Infocom. And the really hardcore Infocom fans, of course, would hopefully buy them both.

In making their pitch to ASC and other potential investors, Bob and Mike felt ethically obligated to make careful note of the seeming headwinds into which their new company would be sailing. But in the end ASC was hugely eager to diversify, and the investment that was being asked of them was relatively small in the context of ASC’s budget. Bob and Mike founded their company on about $500,000, the majority of which was provided by ASC, alongside a handful of smaller investments from friends and family. (Those with a stake in Bob’s old company Challenge also saw it rolled over into the new company.) ASC would play a huge role during this formative period, up to and including providing the office space out of which the first games would be developed.

An ASC press release dated January 8, 1990, captures the venture, called GameWorks at the time, at this embryonic stage of high hopes and high uncertainty. Bob Bates is quoted as saying that “GameWorks products combine the best of several existing technologies in an exciting new format,” while Mike Verdu, who would remain in his old role at ASC in addition to his new one as a software entrepreneur for another couple of years, says that “ASC’s interest in this venture stems from more than just making money over the short term. The goal is to establish a self-sustaining software-publishing company.” Shortly after this press release, the name of said company would be changed from GameWorks to Legend Entertainment, harking back to the pitch for an “Immortal Legends” series of games that had first won Bob a contract with Infocom.

The part of the press release that described GameWorks/Legend as a “software-publishing company” was an important stipulation. Mike Verdu:

I remember making these spreadsheets early on, trying to understand how companies made money in this business. It became very clear to me very quickly that life as an independent developer, without the publishing, was very tough. You scrambled for advances, and the royalties you got off a game would never pay for the advances unless you had a huge hit. Your destiny was so tied to the publisher, to the vagaries of the producer that might get assigned to your title, that it just was not an appealing path at all.

In a very fundamental way, Legend needed to be a publisher as well as a developer if they were to bring their vision of text adventures in the 1990s to fruition. It was highly doubtful whether any of the other publishers would be willing to bother with the niche market for text adventures at all when there were so many other genres with seemingly so much greater commercial potential. In addition, Bob and Mike knew that they needed to have complete control of their products, from the exact games they chose to make to the way those games were packaged and presented on store shelves. They recognized that another part of becoming the implicit successor to Infocom must be trying as much as possible to match the famous Infocom packaging, with the included “feelies” that added so much texture and verisimilitude to their interactive fictions. One of the most heartbreaking signs of Infocom’s slow decline, for fans and employees alike, had been the gradual degradation of their games’ physical presentation, as the cost-cutters in Mediagenic’s Silicon Valley offices took away more and more control from the folks in Cambridge. Bob and Mike couldn’t afford to have their company under a publisher’s thumb in similar fashion. At the same time, though, a tiny company like theirs was in no position to set up its own nationwide distribution from warehouse to retail.

It was for small publishers facing exactly this conundrum that Electronic Arts and Mediagenic during the mid-1980s had pioneered the concept of the “affiliated label.” An affiliated label was a small publisher that printed their own name on their boxes, but piggy-backed — for a fee, of course — on the network of a larger publisher for distribution. By the turn of the decade, the American computer-games industry as a whole had organized itself into eight or so major publishers, each with an affiliated-label program of one stripe or another of its own, with at least several dozen more minor publishers taking advantage of the programs. As we’ve seen in other articles, affiliated-label deals were massive potential minefields that many a naive small publisher blundered into and never escaped. Nevertheless, Legend had little choice but to seek one for themselves. Thanks to Mike Verdu’s research, they would at least go in with eyes open to the risk, although nothing they could do could truly immunize them from it.

In seeking a distribution deal, Legend wasn’t just evaluating potential partners; said partners were also evaluating them, trying to judge whether they could sell enough games to make a profitable arrangement for both parties. This process, like so much else, was inevitably complicated by Legend’s determination to defy all of the conventional wisdom and continue making text adventures — yes, text adventures with graphics and sound, but still text adventures at bottom. And yet as Bob and Mike made the rounds of the industry’s biggest players they generally weren’t greeted with the incredulity, much less mockery, one might initially imagine. Even many of the most pragmatic of gaming executives felt keenly at some visceral level the loss of Infocom, whose respect among their peers had never really faded in tune with their sales figures — who, one might even say, had had a certain ennobling effect on their industry as a whole. So, the big players were often surprisingly sympathetic to Legend’s cause. Whether such sentiments could lead to a signature on the bottom line of a contract was, however, a different matter entirely. Most of the people who had managed to survive in this notoriously volatile industry to this point had long since learned that idealism only gets you so far.

For some time, it looked like a deal would come together with Sierra. Ken Williams, who never lacked for ambition, was trying to position his company to own the field of interactive storytelling as a whole. Text adventures looked destined to be a very small piece of that pie at best in the future, but that piece was nevertheless quite possibly one worth scarfing up. If Sierra distributed Legend’s games and they proved unexpectedly successful, an acquisition might even be in the cards. Yet somehow a deal just never seemed to get done. Mike Verdu:

There seemed to be genuine interest [at Sierra], but it was sort of like Zeno’s Paradox: we’d get halfway to something, and then close that distance by half, and then close that distance by half, and nothing ever actually happened. It was enormously frustrating — and I never could put my finger on quite why, because there seemed to be this alignment of interests, and we all liked each other. There was always a sense of a lot of momentum at the start. Then the momentum gradually died away, and you could never actually get anything done. Now that I’ve become a little more sophisticated about business, that suggests to me that Ken was probably running around trying to make a whole bunch of things happen, and somebody inside his company was being the sort of check and balance to his wanting to do lots and lots of stuff. There were probably a lot of things that died on the vine inside that company.

Instead of Sierra, Legend wound up signing a distribution contract with MicroProse, who were moving further and further from their roots in military simulations and wargames in a bid to become a major presence in many genres of entertainment software. Still, “Wild Bill” Stealey, MicroProse’s flamboyant chief, had little personal interest in the types of games Legend proposed to make or the niche market they proposed to serve. Mike Verdu characterizes Sierra’s interest as “strategic,” while MicroProse’s was merely “convenient,” a way to potentially boost their revenue picture a bit and offset a venture into standup-arcade games that was starting to look like a financial disaster. MicroProse hardly made for the partner of Legend’s dreams, but needs must. Wild Bill was willing to sign where Ken Williams apparently wasn’t.

In the midst of all these efforts to set up the infrastructure for a software-publishing business, there was also the need to create the actual software they would publish. Bob Bates’s time-travel game fell onto the back-burner, a victim of the limited resources to hand and the fact that so much of its designer’s time was being monopolized by practical questions of business. But not so Steve Meretzky’s game. As was his wont, Meretzky had worked quickly and efficiently from his home in Massachusetts to crank out his design. Legend’s two-man programming team, consisting still of the Challenge veterans Duane Beck and Mark Poesch, was soon hard at work alongside contracted outside artists and composers to bring Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls, now planned as Legend’s sole release of 1990, to life in all its audiovisual splendor.

Setting aside for the moment all those planned audiovisual enhancements, just creating a reasonable facsimile of the core Infocom experience presented a daunting challenge. Throughout Infocom’s lifespan, from the 1980 release of Zork I through Bob Bates’s own 1989 Infocom game Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur, no other company had ever quite managed to do what Legend was now attempting to do: to create a parser as good as that of Infocom. Legend did have an advantage over most of Infocom’s earlier would-be challengers in that they were planning to target their games to relatively powerful machines with fast processors and at least 512 K of memory. The days of trying to squeeze games into 64 K or less were over, as were the complications of coding to a cross-platform virtual machine; seeing where the American market was going, Legend planned to initially release their games only for MS-DOS systems, with ports to other platforms left only as a vague possibility if one of their titles should prove really successful. Both the Legend engine and the games that would be made using it were written in MS-DOS-native C code instead of a customized adventure programming language like Infocom’s ZIL, a decision that also changed the nature of authoring a Legend game in comparison to an Infocom game. Legend’s designers would program many of the simpler parts of their games’ logic themselves using their fairly rudimentary knowledge of C, but would always rely on the “real” programmers for the heavy lifting.

But of course none of these technical differences were the sort of things that end users would notice. For precisely this reason, Bob Bates was deeply worried about the legal pitfalls that might lie in attempting to duplicate the Infocom experience so closely from their perspective. The hard fact was that he, along with his two programmers, knew an awful lot about Infocom’s technology, having authored two complete games using it, while Steve Meretzky, who had authored or coauthored no less than seven games for Infocom, knew it if anything even better. Bob worried that Mediagenic might elect to sue Legend for theft of trade secrets — a worry that, given the general litigiousness of Mediagenic’s head Bruce Davis, strikes me as eminently justified. To address the danger, Legend elected to employ the legal stratagem of the black box. Bob sat down and wrote out a complete specification for Legend’s parser-to-be. (“It was a pretty arcane, pretty strange exercise to do that,” he remembers.) Legend then gave this specification for implementation to a third-party company called Key Systems who had never seen any of Infocom’s technology. “What came back,” Bob says, “became the heart of the Legend engine. Mark and Duane then built additional functionality upon that.” The unsung creators of the Legend parser did their job remarkably well. It became the first ever not to notably fall down anywhere in comparison to the Infocom parser. Mediagenic, who had serious problems of their own monopolizing their attention around this time, never did come calling, but better safe than sorry.

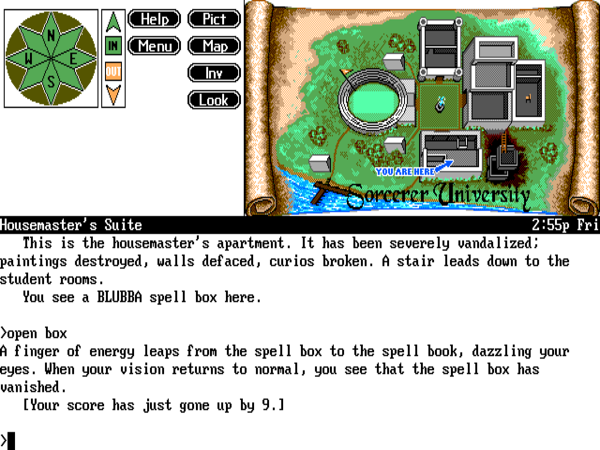

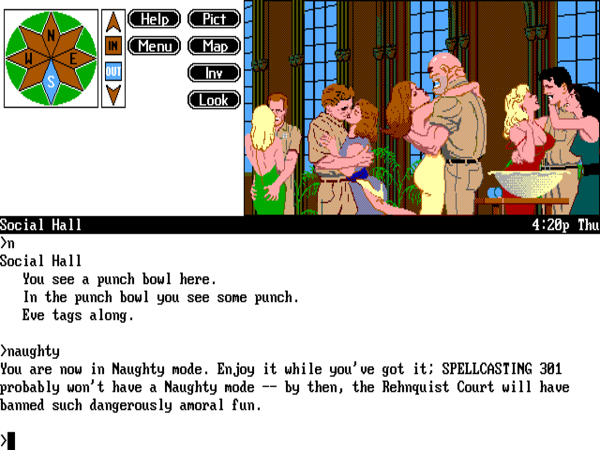

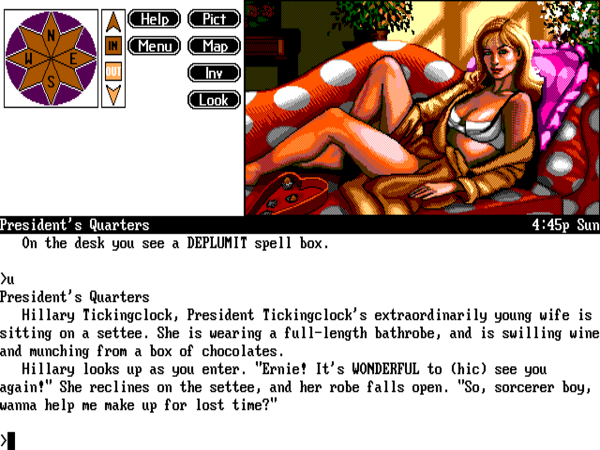

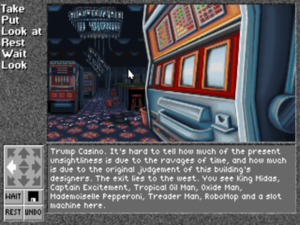

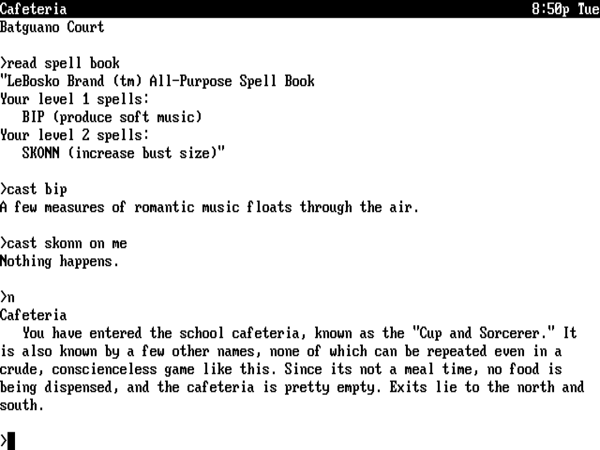

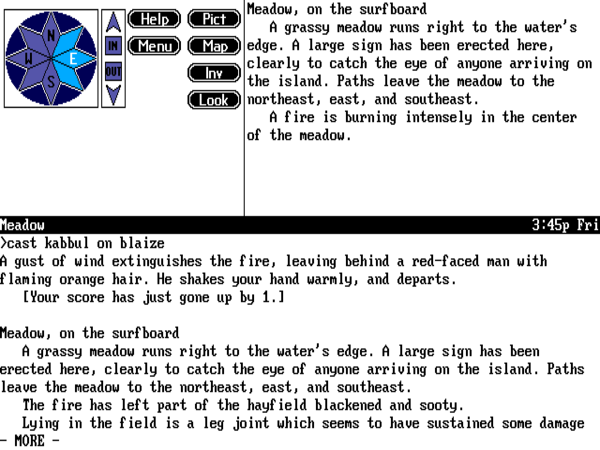

The Legend Interface in a Nutshell

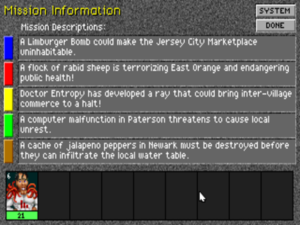

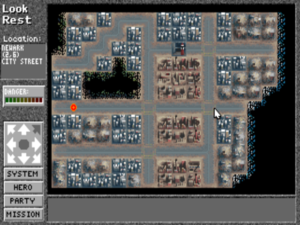

A game can be played in one of three modes. This one, the default, is the most elaborate — not to say cluttered. Note the long menus of verbs — 120 (!) of them, with a commonly used subset thankfully listed first — and nouns to the left. (And don’t worry, this area from Spellcasting 101 is a “fake” maze, not a real one.)

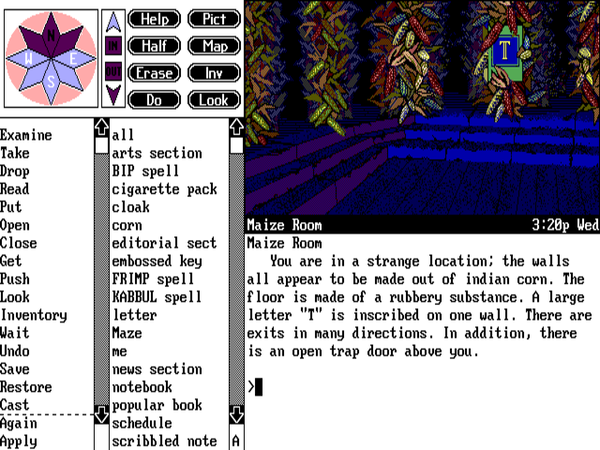

A second mode, which I suspect was the most commonly used by real players in the wild, removes the command-entry menus in favor of allowing more space for the text window, but retains the compass rose and illustrations.

Finally, strict adherents to the ethos of text-and-only-text can indeed play the game as a text-only adventure. The existence of significant numbers of such purists was probably more theoretical than actual, but Legend accommodated them nevertheless.

By tapping the function keys, you can replace the illustration with the current room description or your current inventory without having to burn a turn on the task.

Anxious to make their games as accessible as possible despite their equally abiding determination to become the implicit heir to Infocom, Legend designed for their new engine a menu-based system for inputting commands that could serve as an alternative to typing them in. Bob Bates, the mastermind behind the system:

One of the biggest barriers to text adventures at the time was that people didn’t know how to type. I knew how to type only because the principal of my high school forced me in my sophomore year to take a typing class instead of a third language. At the time, typing was for girls; men didn’t type. It was a barrier for players.

So, we said that we need an interface that will let somebody play using only the mouse. This was a huge problem. How do you do that without giving too much away? One day as I was pondering this, I realized that once you select a verb you don’t need another verb. So, the menu that contains verbs can go away. You’re looking at a list of verb/noun [combinations]: “get box,” “kick wall.” But if you want a sentence with a preposition, once you’ve clicked on the verb you don’t need another verb, so you can replace that first [verb] list with prepositions — and not only that, but prepositions that are only appropriate to that verb. That was an actual insight; that was a cool idea.

The menu on the left had the twenty or so most common verbs first, but underneath that, going down in alphabetical order, was a list of many, many more verbs. You could scroll down in that list, and it might actually suggest interactions you hadn’t thought of. Basically it preserved the openness of the interaction, but avoided the other big bugaboo of parser-driven games: when the parser will come back and say, “I don’t understand that.” With this system, that could never happen. And that was, I thought, huge. Everything was there in front of you if you could figure out what to do. [Parsing errors] became a thing of the past if you wanted to play in that mode.

Then of course we had full-screen text mode if you wanted to play that way, and we had a sort of hybrid half-and-half mode where there was parser-driven text across the bottom, but you still had graphics at the top. I thought it was important that players could play the game the way they wanted to, and I thought it added to the experience by taking away two of the big problems. One was people who didn’t like to type or couldn’t type or were two-finger typists. Number two was when you would type a whole command and there was an error in the first word; the parser says, “I don’t know that word,” and you have to type the whole command again. That interface took away that pain in the ass.

While Bob’s points are well taken, particularly with regard to the lack of typing skills among so much of the general public at the time, the Legend menu-based interface looks very much of its time today. Having the menu appear onscreen by default has had the unfortunate side-effect of making the Legend games look rather cluttered and ugly in contrast to the Infocom classics, with their timeless text-only approach. That does a real disservice to the games hidden inside the Legend interface, which often stand up very well next to many of the works of Infocom.

Aesthetics aside, I remain skeptical of the real long-term utility of these sorts of interfaces in general, all the rage though they were during the twilight of the text adventure’s commercial era. Certainly there must come a point where picking through a list of dozens of verbs becomes as confusing as trying to divine the correct one from whole cloth. A better solution to the guess-the-verb problem is to create a better parser — and, to be fair, Legend games give no ground for complaint on that score; text-adventure veteran though I admittedly am, I can’t recall ever struggling to express what I was trying to do to a Legend game. The problem of correcting typos without having to type the entire command again, meanwhile, could have been efficiently addressed by including a command-history buffer that the player could navigate using the arrow keys. The omission of such a feature strikes me as rather inexplicable given that the British company Level 9 had begun to include it in their games as far back as 1986.

Although I don’t believe any serious surveys were ever made, it would surprise me if most Legend players stuck with the menu-based interface for very long once they settled down to play. “I played the game this way for fifteen minutes before deciding to bag it and type in all my commands,” wrote one contemporary Spellcasting 101 reviewer who strikes me as likely typical. “For me, this was quicker.” “Frankly, I find the menu to be of little use except to suggest possible commands in tough puzzle situations,” wrote another. Even Steve Meretzky, the author of Legend’s first game, wasn’t a fan:

The impetus for the interface was not a particular feeling that this was a good/useful/friendly/clever interface, but rather a feeling that text adventures were dying, that people wanted pictures on the screen at all times, and that people hated to type. I never liked the interface that much. The graphic part of the picture was pretty nice, allowing you to move around just by double-clicking on doors in the picture, or pick things up by double-clicking on them. But I didn’t care for the menus for a number of reasons. One, they were way more kludgey and time-consuming than just typing inputs. Two, they were giveaways because they gave you a list of all possible verbs and all visible objects. Three, they were a lot of extra work in implementing the game, for little extra benefit. And four, they precluded any puzzles which involved referring to non-visible objects.

Like Meretzky, I find other aspects of the Legend engine much more useful than the menu-based command interface. In the overall baroque-text-adventure-interface sweepstakes, Magnetic Scrolls’s Magnetic Windows-based system has the edge in features and refinement, but the Legend engine does show a real awareness of how real players played these types of games, and gives some very welcome options for making that experience a little less frustrating. The automap, while perhaps not always quite enough to replace pen and paper (or, today, Trizbort), is nevertheless handy, and the ability to pull up the current room description or your current inventory without wasting a turn and scrolling a bunch of other text away is a godsend, especially given that there’s no scrollback integrated into the text window.

The graphics and music in the Legend games still hold up fairly well as well, adding that little bit of extra sizzle. (The occasional digitized sound effects, on the other hand, have aged rather less well.) Right from the beginning with Spellcasting 101, Legend proved willing to push well beyond the model of earlier, more static illustrated text adventures, adding animated opening and closing sequences, interstitial graphics in the chapter breaks, etc. It’s almost enough to make you forget at times that you’re playing a text adventure at all — which was, one has to suspect, at least partially the intention. Certainly it pushes well beyond what Infocom managed to do in their last few games. Indeed, I’m not sure that anyone since Legend has ever tried quite so earnestly to make a real multimedia production out of a parser-based game. It can make for an odd fit at times, but it can be a lot of fun as well.

Spellcasting 101 was released in October of 1990, thereby bringing to a fruition the almost eighteen months of effort that had followed that fateful Cinco de Mayo when Bob Bates had learned that Infocom was going away. I plan to discuss the merits and demerits owed to Spellcasting 101 as a piece of game design in my next article. For now, it should suffice to say that the game and the company that had produced it were greeted with gushing enthusiasm by the very niche they had hoped to reach. Both were hailed as the natural heirs to the Infocom legacy, carrying the torch for a type of game most had thought had disappeared from store shelves forever. Questbusters magazine called Spellcasting 101 the “Son of Infocom” in their review’s headline; the reviewer went on to write that “what struck me most about the game is that it is exactly as I would have expected Infocom games to be if the company was still together and the veteran designers were still working in the industry. I kid you not when I say to watch Legend over the years.” “It’s such a treat to play an Infocom adventure again,” wrote the adventuring fanzine SynTax. “I know it isn’t an Infocom game as such, but I can’t help thinking of it as that.”

This late in the day for the commercial text adventure, it was these small adventure-centric publications, along with the adventure-game columnists for the bigger magazines, who were bound to be the most enthusiastic. Nevertheless, Spellcasting 101 succeeded in proving the thesis on which Bob Bates and Mike Verdu had founded Legend Entertainment: that there were still enough of those enthusiasts out there to support a niche company. In its first six months on the market, Spellcasting 101 sold almost 35,000 units, more than doubling Bob and Mike’s cautious prediction of 16,000 units. By the same point, the Legend hint line had fielded over 35,000 calls. For now — and it would admittedly be just for a little while longer — people were buying and, as the hint-line calls so amply demonstrated, playing a text adventure again in reasonable numbers, all thanks to the efforts of two men who loved the genre and couldn’t quite let it go.

A “Presentation to Stockholders and Directors” of Legend from May of 1991 provides, like the earlier ASC press release, another fascinating real-time glimpse of a business being born. At this point Timequest, Bob Bates’s “classical” time-travel adventure, is about to be released at last, Spellcasting 201 is already nearing completion, and a first licensed game is in the offing, to be based on Frederick Pohl’s Gateway series of science-fiction novels. “MicroProse has done an outstanding job of selling and distributing the product,” notes the report, but “has been less than responsive on the financial side of the house. Our financial condition is precarious. We spent most of the Spellcasting 101 revenues in development of Timequest. We are living hand to mouth. We have come a long way and we are building a viable business, but the costs were greater than expected and the going has often been rough.”

Rough going and living hand to mouth were things that Legend would largely just have to get used to. The games industry could be a brutal place, and a tiny niche publisher like Legend was all but foreordained to exist under a perpetual cloud of existential risk. Still, in return for facing the risk they were getting to make the games they loved, and giving the commercial text adventure a coda absolutely no one had seen coming on that unhappy day back in May of 1989. “We did more things right than we did wrong,” concludes the May 1991 report. “This is a workable definition of survival.” Survival may have been about the best they could hope for — but, then again, survival is survival.

(Sources: Questbusters of March 1991; SynTax Issue 11; Computer Gaming World of November 1990 and March 1991; the book Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; Bob Bates’s interview for Jason Scott’s Get Lamp documentary, which Jason was kind enough to share with me in its entirety. But the vast majority of this article is drawn from my interviews with Bob Bates and Mike Verdu; the former dug up the documents mentioned in the article as well. My heartfelt thanks to both for making the time to talk with me and to answer my many nitpicky questions about events of more than 25 years ago.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. |

|---|